Abstract

This study aims to bridge the research on the internationalization of small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) with the literature on initial public offerings (IPOs). It investigates how IPOs affect SMEs’ foreign investment decisions as they internationalize. We argue that IPOs enable SMEs to engage in a period of accelerated foreign expansion, resulting in a wave-like pattern, as suggested by Håkanson and Kappen’s (J Int Bus Stud 48(9):1103–1113, 2017) ‘Casino model’ of internationalization. We also propose that there will be a post-IPO shift in SMEs entering less familiar locations and towards taking higher ownership stakes in new subsidiaries. We use a difference-in-differences design combined with coarsened exact matching to isolate the effects of IPOs. Our analysis of overseas investments by a matched sample of newly listed Japanese manufacturing SMEs and their private counterparts provides strong evidence that SMEs accelerate the pace of establishing new foreign subsidiaries after going public. The results also reveal nuanced changes in the location and ownership patterns in the post-IPO period. This study identifies the IPO as a significant antecedent to SME foreign expansion and offers a new explanation for intertemporal variance in the pace, direction, and commitment of the SME internationalization process.

Résumé

Cet article vise à rapprocher la recherche portée sur l'internationalisation des petites et moyennes entreprises (Small and Medium-sized Enterprises - SMEs) et la littérature en offres publiques initiales (Initial Public Offerings - IPOs). Il étudie comment les IPOs influent sur les décisions d'investissement étranger des SMEs à mesure qu'elles s'internationalisent. Nous argumentons que les IPOs permettent aux SMEs de s'engager dans une période d'expansion étrangère accélérée, générant un modèle en forme de vague comme suggéré par le modèle d'internationalisation « Casino » de Håkanson et Kappen (2017). Nous avançons également qu'il y aura un changement post-IPO pour les SMEs entrant dans des localisations moins familières et vers la prise de participation plus importante dans de nouvelles filiales. Nous utilisons un modèle des doubles différences, combiné à un appariement exact grossier, afin d’isoler les effets des IPOs. Notre analyse sur les investissements à l'étranger d’un échantillon apparié de SMEs manufacturières japonaises nouvellement cotées et de leurs homologues privés démontre de manière robuste que les SMEs accélèrent la vitesse de la création des nouvelles filiales étrangères après leur introduction en bourse. Les résultats révèlent également les changements nuancés dans les configurations de localisation et de propriété au cours de la période post-IPO. Cette recherche identifie l’IPO comme un antécédent significatif à l'expansion des SMEs à l'étranger, et apporte une nouvelle explication de la variation intertemporelle dans la vitesse, la direction et l'engagement du processus d'internationalisation des SMEs.

Resumen

Este estudio tiene como finalidad unir la investigación sobre la internacionalización de las pequeñas y medianas empresas (pyme) con la literatura sobre ofertas públicas iniciales (OPI). Investiga cómo las OPI afectan las decisiones de inversión extranjera de las pymes a medida que se internacionalizan. Argumentamos que las OPI permiten a las pymes comprometerse en un período de expansión extranjera acelerada, lo que resulta en un patrón ondulatorio como lo sugiere el "modelo de casino" de Håkanson y Kappen (2017). También proponemos que habrá un cambio posterior a la oferta pública inicial en las pymes que entren a lugares menos conocidos y hacia la toma de mayores participaciones en las nuevas filiales. Utilizamos un diseño de diferencia en diferencias combinado con una coincidencia exacta gruesa para aislar los efectos de las OPI. Nuestro análisis de las inversiones en el extranjero realizado por una muestra combinada de pymes manufactureras japonesas recientemente cotizadas y sus contrapartes privadas proporciona pruebas sólidas de que las pymes aceleran la velocidad de establecimiento de nuevas filiales extranjeras después de salir a bolsa. Los resultados también revelan cambios matizados en la ubicación y los patrones de propiedad en el período posterior a la salida a bolsa. Este estudio identifica la OPI como un antecedente significativo de la expansión en el extranjero de las pymes y ofrece una nueva explicación de la varianza intertemporal en la velocidad, la dirección y el compromiso del proceso de internacionalización de las pymes.

Resumo

Este estudo tem como objetivo ligar a pesquisa sobre internacionalização de pequenas e médias empresas (SMEs) com a literatura sobre ofertas públicas iniciais (IPOs). Ele investiga como IPOs afetam decisões de investimento estrangeiro de SMEs ao se internacionalizarem. Argumentamos que IPOs permitem que SMEs se envolvam em um período de acelerada expansão estrangeira, resultando em um padrão de onda, conforme sugerido por Håkanson e Kappen (2017) em ‘modelo de cassino’ de internacionalização. Também propomos que haverá uma mudança pós-IPO em SMEs entrando em locais menos familiares e em direção a uma maior participação acionária em novas subsidiárias. Usamos um design de diferença em diferenças combinado com correspondência exata simplificada para isolar os efeitos de IPOs. Nossa análise de investimentos no exterior por uma amostra correspondente de SMEs manufatureiras japonesas recém-listadas e suas contrapartes privadas fornece fortes evidências de que SMEs aceleram o ritmo de estabelecimento de novas subsidiárias estrangeiras após abrirem o capital. Os resultados também revelam leves mudanças nos padrões de localização e propriedade no período pós-IPO. Este estudo identifica o IPO como um antecedente significativo para a expansão estrangeira de SMEs e oferece uma nova explicação para a variação intertemporal no ritmo, direção e comprometimento do processo de internacionalização de SMEs.

摘要

本研究旨在将有关中小企业 (SME) 国际化的研究与有关首次公开募股 (IPO) 的文献联系起来。它调查了 IPO 如何影响SME在国际化过程中的外国投资决策。我们认为, IPO 使SME能够进入加速的海外扩张期, 从而产生 Håkanson 和 Kappen (2017) 所提出的国际化“赌场模型”的波浪模式。 我们还建议将会出现SME进入不太熟悉的地区, 并朝着在新的子公司中获得更高所有权股份的方向发展的后IPO转变。我们使用双重差分法结合粗化精确匹配来找出IPO 的影响。我们通过对新上市的日本制造业的SME及其私营企业的匹配样本海外投资的分析提供了SME在上市后加快了建立新外国子公司的步伐的**有力的证据。研究结果还揭示了后IPO时期地点和所有权模式的细微变化。本研究将IPO确定为SME海外扩张的重要前因, 并为SME国际化进程的步伐、方向和承诺的跨期差异提供了新解释。

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

Internationalization is of great strategic significance to the evolution and performance of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) (Lu & Beamish, 2001; Schwens, Zapkau, Bierwerth, Isidor, Knight, & Kabst, 2018). Yet, international expansion is a complex and resource-taxing process and is especially challenging for SMEs, which typically have limited financial resources (Buckley, 1989; De Maeseneire & Claeys, 2012; Hollenstein, 2005). Recognizing the financial constraints SMEs generally face, many prior studies focus on how their intangible resources, such as marketing skills, innovativeness, market orientation, management know-how, and social networks, may offer compensating advantages during internationalization and thereby shape SMEs’ foreign expansion decisions (Golovko & Valentini, 2011; Knight & Kim, 2009; Musteen, Datta, & Butts, 2014; Oehme & Bort, 2015). Although the literature acknowledges that financial constraints might impede the SME internationalization process, there is limited systematic research on how SMEs’ foreign investment decisions might change when any financial constraints are relaxed, such as when they undertake initial public offerings (IPOs).

This research gap has an important connection to the ongoing debate about the fundamental logics and patterns of the internationalization process. The Uppsala model suggests that firms expand overseas through incremental investments as they gain experience in the local market (Johanson & Vahlne, 1977). However, Håkanson and Kappen (2017) (hereafter, H&K) recently proposed that the internationalization process proceeds in a wave-like pattern, rather than incrementally. Based on a re-interpretation of the data from the seminal studies (Johanson & Vahlne, 1977; Johanson & Wiedersheim-Paul, 1975), their ‘Casino model’ of internationalization posits that firms aim to capitalize on existing local market opportunities by deploying and exploiting “non-location-bound, general internationalization capabilities” (Håkanson & Kappen, 2017: 1108) and to diversify risk by placing multiple bets through the concurrent establishment of multiple foreign operations. These authors also note that a period of intensified foreign expansion requires significant resources and, thus, “a firm’s propensity to engage in ‘casino internationalization’ is clearly contingent on the quantity of available financial and other resources at its disposal” (Håkanson & Kappen, 2017: 1106, italicized in original). However, while H&K recognized financial availability as a primary consideration, relevant antecedents to the wave-like pattern remain underspecified. Moreover, their claims have yet to be subjected to further hypothesis testing in different contexts, and there is need for empirical evidence of intertemporal variation in internationalization activities to substantiate the complementarity of the Casino model to the Uppsala model.

The IPO context provides an interesting and appropriate context for investigating these ideas for several reasons. Research in corporate finance emphasizes that IPOs can bring about a significant change in firms’ financial resource endowments, and SMEs account for a substantial share of the global IPO market (Ritter, Signori, & Vismara, 2013). IPOs serve as the point of entry to the public equity markets and give SMEs expanded access to capital, allowing them to develop and pursue new growth opportunities. In addition to accessing equity capital, IPOs can further reduce SMEs’ financial limitations, for instance, by lowering borrowing costs vis-à-vis private firms (Aktas, Andries, Croci, & Ozdakak, 2019). Accordingly, newly public firms have been found to accelerate corporate development through acquisitions (Brau, Couch, & Sutton, 2012), investment in R&D and capital expenditures (Kim & Weisbach, 2008), and aggressive product market strategies (Chod & Lyandres, 2011). In view of the implications of IPOs with respect to capital availability, they are likely to shape an SME’s foreign investment decisions and, in particular, might facilitate a wave of intensified foreign expansion in the post-IPO period.

Notwithstanding the potential enabling effect of financial resources, research on the growth of MNEs using a Penrosean lens suggests that managerial resources also have a key role in determining the patterns of foreign expansion (Tan, Su, Mahoney, & Kor, 2020). The original Uppsala model had its roots in Penrose’s work that views firm-specific managerial knowledge as a key organizational resource. Her classic theory of the growth of the firm suggests that although improved capital availability can enable and incentivize the firm to acquire new knowledge and managerial talent (Penrose, 1959; Pitelis, 2007), the supply of firm-specific managerial resources is typically inelastic in the short run and there are adjustment costs when existing managerial resources need to be reallocated or altered to meet requirements in foreign markets (Mohr, Batsakis, & Stone, 2018). Thus, newly public firms, especially SMEs, may face a scarcity of managerial resources, which could limit the extent of foreign expansion in the post-IPO period. Thus, it is not obvious a priori whether and how a wave of intensified foreign expansion may occur following IPOs. Yet, to date, research on the relationship between IPOs and SME foreign investment has been scarce, despite the fact that both actions can have long-lasting implications for firm growth and IPOs directly address financial constraints that can hinder internationalization (Certo, Holcomb, & Holmes, 2009). Furthermore, prior internationalization research, including the Uppsala model and the Casino model, tends to focus on relatively stable firms, and has paid limited attention to periods of destabilization when firms’ resource endowments and/or governance structures change significantly, such as the years shortly after firms undertake IPOs. Thus, an analysis of the relationship between IPOs and SME internationalization has the potential to contribute insights to the research on the internationalization process and the IB literature more broadly.

In this study, we therefore aim to bridge the research on SME internationalization and the IPO literature to investigate the following research question: how do IPOs affect SMEs’ foreign investment decisions? IPOs improve SMEs’ access to the capital market, an important yet neglected factor market in previous research that can foster internationalization. This potentially allows SMEs to implement a growth strategy on an international scale in a short period of time, which may be difficult for comparable private SMEs. Therefore, by focusing on financial resources as a critical tangible resource which SMEs must access in factor markets, and more specifically on the discrete event of an IPO that substantially improves financial resource availability, our analysis builds upon and extends prior research that emphasizes the role of intangible resources in the internationalization process of SMEs (Filatotchev & Piesse, 2009; Knight & Kim, 2009). Our analysis relies on a unique dataset and empirical design that enable us to discern intertemporal variation between the pre- and post-IPO periods and to investigate whether a wave-like pattern suggested by the Casino model exists during this important transition in the development of SMEs.

Drawing on the IPO and the internationalization process literatures, we suggest that there will be a period of intensified international expansion after SMEs undertake IPOs. These firms will more frequently engage in foreign direct investment (FDI) in the post-IPO period compared to the pre-IPO period. We also develop and contextualize the arguments from H&K to hypothesize that IPOs will also have a bearing on the location and ownership patterns of the newly established subsidiaries. More specifically, we propose that compared to the pre-IPO period, newly public SMEs will be more likely to invest in locations with which they are not familiar, and they will tend to hold higher rather than lower ownership stakes in new subsidiaries in the post-IPO period. As such, our study simultaneously investigates three key dimensions, namely the pace, direction, and commitment of SMEs’ internationalization process (Gao & Pan, 2010; Vermeulen & Barkema, 2002). This analytical approach not only captures the multifaceted nature of FDI decisions, but also extends previous research that primarily focused on the effects of financial resources on firms’ overall tendency to invest overseas (De Maeseneire & Claeys, 2012; Forssbæck & Oxelheim, 2008).

We test our hypotheses using data on overseas investments by Japanese manufacturing SMEs. Our estimation strategy employs a difference-in-differences design and a matching procedure (i.e., coarsened exact matching) to address endogeneity concerns. More specifically, the matched sample includes a group of newly public SMEs and a group of control firms that remained private but operated in the same industry as the newly public SMEs and closely resembled them in size, level of internationalization at the time of the IPO, and the tendency to invest overseas in the pre-IPO period. Balancing on these pre-IPO conditions across the treatment and control firms mitigates potential unobserved heterogeneity associated with the IPO event. We also advance prior research on IPO firms that often only focuses on newly public firms and is therefore subject to potential selection biases.

The results of the analyses largely support our hypotheses. The newly public SMEs established more foreign subsidiaries in the post-IPO years than before going public. New entries in different location and ownership categories all increased significantly. Newly public SMEs exhibited a greater propensity to enter host countries they had not previously invested in before the IPO, yet their FDI was not more pronounced in non-home regions than in the home region. Furthermore, newly public SMEs were more likely to have majority rather than a minority stakes in new subsidiaries. However, they did not exhibit a significantly greater tendency to establish wholly owned subsidiaries (WOSs) than international joint ventures (IJVs). The main findings are robust to alternate matching procedures and subsample analyses.

This study makes several contributions to the literature. Both IB and IPO scholars have noted a gap in our understanding of the relationship between IPOs and foreign expansion (Certo et al., 2009; Engelen, Heugens, van Essen, Turturea, & Bailey, 2020). More broadly, although capital availability is considered important to SMEs’ international expansion, its effects on FDI have traditionally not been examined in detail or through the particular lens of public equity financing. Our study addresses the lack of understanding on how IPOs shape SMEs’ FDI decisions. Connecting two largely separate literatures on IPOs and SME internationalization, we propose and test new explanations for the drivers of FDI by SMEs by investigating the intertemporal variance in the pace, direction, and commitment of their investment decisions around the IPO. Evidence of a wave of heightened foreign expansion after the IPO supports the Casino model. In addition, our analysis not only confirms the IPO as an important antecedent to the wave-like pattern, but also extends the main empirical prediction of the Casino model by identifying shifts in the location and ownership patterns of foreign investments. Finally, despite uncovering evidence consistent with the Casino model in the post-IPO period, our findings indicate that the Uppsala model still partially captures some aspects of the internationalization process not emphasized in the Casino model (e.g., some of the specific location and ownership dimensions of internationalization that we document), illustrating the complementarity between the two models, especially during a time of substantial corporate growth and change.

THEORY AND HYPOTHESES

Theoretical Background

Reviews of research on SME internationalization consistently recognize the Uppsala model as a foundational and central theoretical lens (Coviello & McAuley, 1999; Dabić, Maley, Dana, Novak, Pellegrini, & Caputo, 2020). The model suggests that a firm’s internationalization process is influenced by accumulated market knowledge and gradually increased commitments over time (Johanson & Vahlne, 1977). The incremental pattern is based on the behavioral assumptions of risk aversion and uncertainty avoidance and is manifested in market selection and the mode of market entry. As the original authors updated the model to give more emphasis to the role of network relations (Johanson & Vahlne, 1990, 2009), they maintain that the structure and general predictions of the model remain the same in that the interplay between the state of a firm’s international operation and incremental changes of resource commitment determines its internationalization path (Vahlne & Johanson, 2017). Highlighting the particular applicability of the model to smaller firms, Johanson and Vahlne (1990) noted that “big firms or firms with surplus resources can be expected to make larger internationalization steps” (p. 12). However, prior work has paid little theoretical attention to financial resource availability and how financial limitations may potentially influence the patterns of the SME internationalization process.

H&K suggest a more explicit role for financial resources in their Casino model of the internationalization process. By re-analyzing the original data that inspired the Uppsala model (Johanson & Vahlne, 1977; Johanson & Wiedersheim-Paul, 1975), they concluded that the observed market entry decisions support an alternative, complementary model of internationalization. H&K argue that firms undertake international expansion on a broader front than the Uppsala model assumes and view opportunity seeking and risk hedging, instead of risk aversion and uncertainty avoidance, as the main drivers of the decision-making process regarding market entries. They also maintain that non-location-bound, general internationalization capabilities are the primary force sha** the internationalization process. As a consequence, firms tend to enter foreign markets in close tandem, when resources permit, to exploit the general internationalization knowledge and gain the economies of scale and scope arising from operating in multiple markets (Håkanson & Kappen, 2017: 1108). Such a portfolio approach towards internationalization results in a wave-like pattern of international expansion, analogous to placing multiple bets at the roulette table to increase the probability of winning while mitigating the overall downside risk. In addition, the Casino model differs from the typical internationalization model of born globals, whose international strategy is mainly focused on opportunity creation and innovative adaption through proactive risk-taking to obtain positions in global niches.

However, while intertemporal variation that characterizes the wave-like pattern is to a large extent determined by the quantity of available financial resources, H&K did not explore what types of financial resources or events are likely to induce a period of intensified foreign expansion. Thus, the particular conditions under which wave-like expansion episodes will materialize remain to be fully specified. Moreover, there is ample evidence that SMEs usually have severe information asymmetry, limited collateralizable assets, and relatively unstable performance and, as a result, often have limited access to capital markets compared to larger firms (Fraser, Bhaumik, & Wright, 2015). Thus, SMEs often face disproportional financial constraints when engaging in product innovation (Canepa & Stoneman, 2008), capital spending (Garmaise, 2008), employment growth (Paglia & Harjoto, 2014), and international expansion (Acs, Morck, Shaver, & Yeung, 1997; Buckley, 1989; Hollenstein, 2005). Therefore, the wave-like pattern is likely to materialize in SMEs when any financial constraints owing to the liability of smalless are relaxed. Research on environmental factors suggests that equity market liberalization and government loan programs can alleviate such financial constraints, and thereby increase SME exports and foster international trade (Fischer & Reuber, 2003; Manova, 2008). These findings imply that regulatory changes and government intervention may contribute to periods of heightened international activities.

These important insights notwithstanding, prior studies present two understudied questions concerning SME international expansion. First, there has been limited research on how an SME’s own financing strategy may directly enhance its access to the capital market and in turn affect its internationalization process. Second, in contrast to the body of research on the relationship between financial constraints and exports (Paul, Parthasarathy, & Gupta, 2017), few studies have examined the impact of capital availability on SMEs’ FDI decisions. Despite the importance of exports to SMEs, research has shown that SMEs do not necessarily eschew FDI, as FDI can be preferable to exporting and generate higher profit levels because it allows for tighter control of and more efficient exploitation of proprietary knowledge (Tang & Yu, 1990).

Only a small number of studies have explored questions related to these two. Though not focusing on SMEs, a study of cross-border acquisitions shows that firms are more likely to invest overseas when they have access to competitively priced equity or debt, or when they are cross-listed in larger, more liquid equity markets (Forssbæck & Oxelheim, 2008). Similarly, Hasan, Kobeissi and Wang (2011) find that cross-listing is positively related to the likelihood of SMEs having foreign sales. Moreover, based on interviews with SME managers, bankers, and venture capitalists (VCs), De Maeseneire and Claeys (2012) find that financiers use unfavorable evaluation methods and have a strong home bias against SMEs’ FDI projects, leading to underinvestment by small firms in foreign markets. Together, these studies imply that improved access to the capital market, for instance through IPOs, is likely to increase an SME’s propensity to engage in FDI.

A crucial stage in the life cycle of equity financing, an IPO drastically changes an SME’s governance structure from private to public, from concentrated to more dispersed ownership, from founder-managers to a board of insider and outsider directors. It provides substantial liquidity and an exit strategy to controlling shareholders and early stage investors (Certo et al., 2009). The increased access to financial resources allows the firm to reconcile current obligations as well as to pursue new growth opportunities, including foreign expansion. Yet, research regarding post-IPO geographic diversification is limited (Certo et al., 2009; Engelen et al., 2020; Reuer & Ragozzino, 2014). Carpenter, Pollock and Leary (2003) find that VC backing is positively related to foreign sales at newly listed SMEs when the board members appointed by the VCs or the top management team (TMT) had extensive international experience. Filatotchev and Piesse (2009) find that high export intensity improves the sales growth of newly listed firms. Although these studies provide useful insights into SME international expansion in the IPO context, their samples only included IPO firms and post-IPO observations. However, to discern potential IPO-induced intertemporal variation in the internationalization process, researchers need to consider investment behaviors in both pre- and post-IPO periods and to compare the patterns at IPO firms to those that remain private. In this study, we aim to isolate the effects of IPOs on SMEs’ FDI by comparing decisions patterns before and after their IPOs.

Research Hypotheses

Much of the extant IPO literature is concerned with the long-term under-performance or the short-term underpricing of IPOs, with a variety of explanatory models focused on information asymmetries within and between the issuers, owners, underwriters, and investors (Boeh & Southam, 2011). A wealth of IPO studies focus on how characteristics of the board (Certo, Daily, & Dalton, 2001), TMT (Filatotchev & Bishop, 2002), CEO (Beatty & Zajac, 1994), VCs (Ragozzino & Reuer, 2007), partnerships and other international activities (Reuer & Ragozzino, 2014), and underwriters (Gulati & Higgins, 2003) can signal the underlying quality of the firm and mitigate the effects of information asymmetry due to adverse selection concerns. In the current study, we are less concerned with IPO performance as an ultimate outcome and focus instead on the relation between the IPO event and the SME’s post-IPO strategic choices. Prior corporate finance research shows that firms generally tend to increase their acquisition activities (Aktas et al., 2019; Brau et al., 2012) and R&D efforts (Kim & Weisbach, 2008), as well as adopt more aggressive marketing strategies following IPOs (Chod & Lyandres, 2011). These findings are consistent with those anticipated for the effects of financial resources on SME internationalization in that IPO facilitates growth in general by providing equity capital and access to additional financing sources.

Researchers have also emphasized the implications of changes in ownership that accompany the IPO for a firm’s risk propensity (Wu, 2012). Less exposure to the international market may limit the growth and profitability of SMEs but can help minimize income uncertainty and the potential loss of personal wealth. Therefore, SME managers with higher ownership have been found to be more risk averse and favor a more conservative approach to foreign expansion (George, Wiklund, & Zahra, 2005). As IPOs give public firms’ owners a greater ability to diversify idiosyncratic risk in the capital market, their tolerance for risky investment projects will be higher than those of private firms (Chod & Lyandres, 2011). IPOs also lead to more dispersed ownership structures and less concentrated corporate control by the controlling shareholders (typically founders, families, and TMTs at SMEs). As a result, these shareholders have less incentive and more difficulty preserving the existing capital, which can lead firms to become less risk averse after IPOs in pursuing growth strategies (Morck, Stangeland, & Yeung, 2000).

The foregoing IPO research suggests that SMEs’ choices regarding foreign investment will vary between the pre- and post-IPO periods. An analysis of such intertemporal variation is ideal for testing the alternative logics of the Casino model and the Uppsala model. In the Uppsala model, the IPO event is unlikely to drastically alter an SME’s state of international operation, especially its overseas networks and its capacity to manage cross-border operations in the short term, because experiential learning and relationship building are continuous, time-consuming processes (Johanson & Vahlne, 1977, 2009). In other words, the knowledge development process that underpins the resource commitment process in the Uppsala model is less likely to be sensitive to any immediate changes in the availability of financial resources brought about by the IPO. In contrast, under the assumptions of opportunity seeking and risk hedging in the Casino model (Håkanson & Kappen, 2017), newly public SMEs are likely to leverage the improved capital availability to expand the international portfolio and pursue growth opportunities in multiple markets, thereby creating a wave of foreign expansion in the post-IPO period.

More specifically, we argue that the pace of foreign entries, which reflects a firm’s underlying propensity to internationalize (Nadolska & Barkema, 2007; Vermeulen & Barkema, 2002), will increase in the post-IPO period, as suggested by the Casino model. From a financial perspective, when an IPO brings new financial resources by expanding an SME’s access to the capital market, the newly public SMEs can invest in their general internationalization capabilities (e.g., hiring additional managers and building administrative systems controlling and coordinating foreign operations) (Håkanson & Kappen, 2017), and pay the high sunk costs (e.g., consumer research, product development, the creation of distribution networks and partnerships, etc.) associated with multiple market entries in a short period of time (Choquette, 2019). Meanwhile, newly public SMEs will be more likely to engage in foreign expansion when the company’s financial viability is unlikely to be threatened under the conditions of greater financial reserves and/or a more diversified international portfolio (Buckley, Chen, Clegg, & Voss, 2018; Jiang & Holburn, 2018). Thus, a newly public SME will be more likely to pursue investment opportunities that would have been deemed too risky “in the spirit of trial-and-error” (Håkanson & Kappen, 2017: 1109), so the SME is less likely to follow a wait-and-see or incremental approach to internationalization (Clarke & Liesch, 2017).

However, despite the importance of financial resources to newly public SMEs, other organizational factors may also influence post-IPO international development. Through a Penrosean lens, a recent review of the research on MNE growth identifies two main internal constraints to international expansion – financial constraints and managerial constraints (Tan et al., 2020). Financial constraints can force MNEs to not only refrain from foreign market entry but may prompt divestitures from existing foreign operations. In addition, MNEs can strategically reduce the cost of financing, for instance by exploiting financial market imperfections, to facilitate internationalization (Yuan, Qian, & Pangarkar, 2016). These findings are consistent with the main themes regarding financial resources from the IPO and the SME internationalization literatures. On the other hand, a firm may encounter managerial constraints when it expands its foreign operation more rapidly than its managerial resources can administer the growth process effectively, which could result in diminished levels of foreign expansion or even foreign divestment in subsequent periods (Goerzen & Beamish, 2007; Mohr et al., 2018). This effect of managerial constraints is closely related to time compression diseconomies in internationalization, which occurs when firms, and SMEs in particular, are limited by their capacity to evaluate and absorb the novel foreign experiences arising from simultaneous expansion along multiple paths (Hutzschenreuter & Voll, 2008; Jiang, Beamish, & Makino, 2014; Vermeulen & Barkema, 2002).

It is thus reasonable to suspect that the pace of post-IPO foreign expansion at newly public SMEs may be constrained if the quantity and quality of managerial resources does not match the greatly enhanced financial resources. However, we argue that the potential negative effect of managerial constraints is likely to be limited in the post-IPO years. Newly public firms often alter their strategies and organizational structures to cope with the expectations for growth from new investors (Certo et al., 2009). Moreover, although a primary assumption of Penrose’s theory is that firm growth is based on the accumulation of managerial knowledge, she maintained that management would engage in deliberate search for innovative use of excess material resources when they become available. In particular, she argued that excess resources will immediately become important to management, “not only because the belief that they exist acts as an incentive to acquire new knowledge, but also because they shape the scope and direction of the search for knowledge” (Penrose, 1959: 77). As a result, she concluded that “both an automatic increase in knowledge and an incentive to search for new knowledge are, as it were, ‘built into’ the very nature of firms possessing entrepreneurial resources of even average initiative” (Penrose, 1959: 78).

This Penrosean perspective implies that a potential lack of managerial resources at newly public SMEs can be at least partially remedied by acquisition of managerial capacity and deliberate search for knowledge motivated by the desire to utilize the enhanced financial resources fully (Pitelis, 2007). For instance, Nickerson (2017) found that increased IPO activity at the industry level leads to a higher demand for managerial talent, which results in a greater likelihood of executive transitions between firms and higher executive compensation. There is also evidence that higher foreign competition is associated with higher demand for managerial talent and more incentive provisions for executives (Cuñat & Guadalupe, 2009). These findings and Penrose’s view on the interaction between material and managerial resources imply that newly public SMEs are likely to increase investment in non-location-bound, general managerial capabilities to facilitate foreign expansion (Håkanson & Kappen, 2017; Rugman & Verbeke, 1992). H&K further argue that once the initial costs of develo**, or acquiring, managerial capacity necessary for foreign expansion have been incurred, the marginal managerial costs of establishing additional subsidiaries will no longer be significant, thus posing little threat to wave-like expansion (p. 1110). Thus, although managerial constraints may temper the pace of foreign expansion at newly public SMEs and thus arguably make it more difficult to detect a positive effect of IPOs on SMEs’ FDI activities, they are unlikely to offset fully the overall impact of improved financial resources. Hence, we posit:

Hypothesis 1:

An IPO has a positive effect on the pace at which an SME establishes new foreign subsidiaries.

A firm’s international strategy is reflected not only in its overall propensity to invest overseas, but also in the direction of its investment (Buckley, 1989; Jiang, Holburn, & Beamish, 2020) and in the levels of resource commitment and control in foreign operations (Brouthers & Nakos, 2004; Gao & Pan, 2010). Though the notion of establishment chain from the Uppsala model provides empirical predictions regarding the location and resource commitment patterns, H&K only found limited effects of psychic distance on location decisions in their re-interpretation of the data from the seminal Uppsala studies, and their Casino model is primarily focused on the intertemporal variation of the overall propensity to invest overseas. However, we argue that the main arguments of the Casino model can be extended to “where” and “how” investments take place and can therefore contribute to the extant IB scholarship on SMEs’ location choices and ownership strategy (Dabić et al., 2020).

In terms of location, entering unfamiliar countries and regions implies greater income uncertainty because it typically involves higher communication and monitoring costs (Jiang, Holburn, & Beamish, 2016), costs to modify and recalibrate organizational routines and structures (Hutzschenreuter & Voll, 2008), and costs of allocating managerial time and effort between different operating environments (Hashai, 2011). Accordingly, research in the Uppsala tradition suggests a path-dependent, incremental pattern in firms’ choices of foreign investment location, where they tend to establish new subsidiaries in existing and familiar locations and gradually venture into new, unfamiliar locations (Chang, 1995; Johanson & Wiedersheim-Paul, 1975). Therefore, if a newly public SME’s general internationalization capabilities and related administrative systems are underdeveloped or insufficiently augmented in the post-IPO period, the SME may be likely to depend on its prior experience in choosing investment location and, consequently, increase its investment in familiar locations more so than in unfamiliar ones.

However, we argue that IPOs by SMEs will have more pronounced effects on their investments in unfamiliar rather than familiar locations in the post-IPO wave of foreign expansion according to the logic of the Casino model. First, from a financial point of view, incremental change of investment direction means that firms need to forego potentially profitable, yet risky investment projects in unfamiliar locations in exchange for lower income uncertainty (Benito & Gripsrud, 1992). Yet, the Casino model suggests that when resources permit, the primary aim of firms’ decisions related to international expansion will be to detect and capitalize on existing market opportunities, and not to wait for the learning to gradually materialize. Thus, newly public SMEs are likely to leverage improved financial resource availability to pay the sunk costs to overcome liabilities of foreignness and outsidership in unfamiliar locations rather than to bear the opportunity costs in the form of foregone growth opportunities (Håkanson & Kappen, 2017: 1111). Furthermore, fewer financial constraints will also increase newly public SMEs’ proclivity to pursue novel strategies and accept location-specific risks when the chance of a failed venture depleting the firm’s financial reserve becomes smaller and an expanded international portfolio simultaneously reduces systemic risk.

Such a broad-front internationalization approach, when amplified by improved capital availability, not only lowers the overall downside risks arising from market uncertainties and/or managers’ partial ignorance, but also allows the firm, especially those in the early stages of internationalization, “to rapidly explore, discover, and act upon opportunities in several markets” (Håkanson & Kappen, 2017: 1106). At the same time, improved access to financial resources tends to enable and motivate the firm to devote more resources to what Penrose (1959: 59) called ‘managerial research’ to obtain new information to reduce subjective uncertainty. Such search would also help improve newly public SMEs’ general internationalization capabilities through the discovery of new ways of extracting productive services from combining new and existing resources and applying them to new markets. Consistent with the key assumptions of opportunity seeking and risk hedging in the Casino model, the deliberate search for novel market knowledge can thus help alleviate potential managerial constraints at newly public SMEs and reduce their dependence on prior international experience in choosing investment locations. Taken together, we argue that IPOs will have more pronounced effects on SMEs’ entry into unfamiliar locations compared to familiar locations. Hence, we posit:

Hypothesis 2:

An SME’s IPO has a greater positive effect on the number of new foreign subsidiaries established in less familiar locations, compared to subsidiaries in more familiar locations.

The foregoing arguments can also be extended to the ownership pattern of subsidiaries established in the post-IPO wave. The Uppsala model suggests that a firm will gradually increase its resource commitment when its risk management capability is enhanced by experiential knowledge (Figueira-de-Lemos, Johanson, & Vahlne, 2011). Consistent with this risk avoidance logic, research has shown that SMEs are more likely than larger firms to expand internationally through non-equity arrangements, and they prefer minority stakes to majority or full ownership when engaging in equity-based investment (Hollenstein, 2005; Laufs & Schwens, 2014). A higher ownership stake offers the firm greater control over the operation and higher potential return but demands higher tolerance for financial risk, whereas a lower ownership stake represents lower levels of resource commitment and financial risk (Anderson & Gatignon, 1986).

We argue that an IPO is likely to alter the trade-offs involved in these resource commitment choices, and as a result SMEs will be more likely to opt for higher rather than lower ownership stakes during FDI in the post-IPO period. From a financial standpoint, and as in the case of location choices, increased capital availability allows the SME to commit to greater outlays for new investments in pursuit of higher return and tighter hierarchical control. At the same time, fewer financial constraints mean that SMEs will be more likely to tolerate the financial and operational risks arising from higher ownership stakes in new subsidiaries.

However, as a majority or sole investor in a foreign subsidiary, the firm may need to commit considerable personnel and managerial time to learning to coordinate with host country governments, business partners and other stakeholders (Goerzen & Beamish, 2007). The increased demand for managerial resources implies that the existing managerial capacities may limit newly public SMEs’ ability to take higher levels of ownership in new investments. Yet, a firm also has an incentive to implement an expansion plan, such as a higher ownership stake, as long as it can provide a way of using the excess financial resources profitably (Penrose, 1959), and the same incentive motivates management to acquire new knowledge and talent and to alter existing administrative functions to facilitate the expansion plan (Pitelis, 2007). Thus, as in the case of location choices, when IPOs increase SMEs’ financial resources substantially, managerial constraints can be partially remedied to support a more aggressive approach towards taking on greater ownership positions in new foreign subsidiaries. Hence, we posit:

Hypothesis 3:

An SME’s IPO has a greater positive effect on the number of new foreign subsidiaries involving a higher ownership stake, compared to subsidiaries involving a lower ownership stake.

METHODS

Empirical Strategy

Examining the relationship between IPOs and foreign investment requires a methodology that takes into account potential endogeneity arising from simultaneity and unobserved variables that are related to both IPO and FDI decisions. To address this challenge, our empirical strategy employs a difference-in-differences (DD) design and a coarsened exact matching (CEM) procedure (Singh & Agrawal, 2011; Teodoridis, Bikard, & Vakili, 2019). The treatment effect is an IPO in the current setting. Accordingly, the treatment group includes SMEs that undertook an IPO in the study period, and the control group includes private SMEs that did not.

The matching procedure identifies treatment and control firms that are balanced on several pre-IPO characteristics to reduce selection bias. Estimating the DD model for the matched sample then allows us to ascertain the impact of IPOs by analyzing the FDI decisions of treatment firms before and after an IPO and comparing the changes in decision patterns with those of control firms. A challenge in some of the existing studies that have examined the internationalization of IPO firms is that they only included IPO firms in their samples and only considered strategic decisions after the IPO. By incorporating information from the pre-IPO period and using the control group to construct the counterfactual outcome experienced by the treatment group, our empirical strategy provides a more robust estimation of the effects of IPOs on SMEs’ international expansion. We detail the data and sample, variable operationalizations, and the matching procedure in the following sections.

Data and Sample

We drew on two databases of Japanese firms to compile longitudinal data that include information on both FDI activities and IPO history. Overseas Japanese Companies Database (OJC database), a yearly publication by Toyo Keizai, provides data on overseas subsidiaries of Japanese MNEs, including information on a subsidiary's parent firm(s), host country, founding year and industry classification. We retrieved data on firms’ listing histories from the Nikkei Economic Electronic Databank System (NEEDS), an authoritative source of corporate data for publicly traded firms in Japan. Using data from NEEDS, we were able to identify the year of IPO when a firm was first listed on the Tokyo Stock Exchange, JASDAQ, or other regional exchanges (e.g., Osaka Securities Exchange).

The Japanese corporate governance system is more relationship oriented and bank centered compared to the more market-oriented systems in the US and the UK (Aoki, 1990). However, research on Japanese IPOs in the early 2000s shows that the largest shareholders of the IPO firms were typically founders or controlling families, with venture capitalists and banks in the distant third and fourth places (Sakawa & Watanabel, 2012). This ownership pattern is similar to IPO firms in other countries (Bruton, Filatotchev, Chahine, & Wright, 2010). Therefore, despite the differences in the corporate governance system, findings based on a Japanese sample can be expected to have reasonable generalizability.

Our analysis examines the establishment of new subsidiaries by Japanese SMEs between 1990 and 2014. We selected this interval of time to capture a period with high levels of FDI by Japanese firms and to exclude potentially irregular investment activities occurring shortly after the signing of the Plaza Accord in late 1985 (Yamawaki, 2007). A DD specification requires observations before and after the treatment event. Prior studies of the effects of IPOs on strategic decisions typically examined a period of 3–5 years after the IPO (Aktas et al., 2019; Brau et al., 2012). Therefore, our analysis includes IPOs that took place between 1995 and 2009 to ensure that there are 5 years of data to observe before and after any IPO.

Following many prior studies on FDI, we focus on parent firms in the manufacturing sector (Delios & Henisz, 2003; Hennart, 1991). Following the classification of SME used by the Japanese Corporation Tax Act,1 our definition of SMEs includes firms that had fewer than 300 employees. We used the number of employees reported in the first publicly available financial statements after the IPO as the proxy for this measure. Merging the OJC and NEEDS databases resulted in 150 manufacturing SMEs that undertook IPOs between 1995 and 2009. Finally, since our study is concerned with the changes in FDI patterns when SMEs transition from private to public status, we included private firms as potential control firms and excluded established public firms whose IPOs predated the study period.

Using the merged data, we assembled an unbalanced firm-year panel that includes 150 newly public SMEs and 2,801 private firms. These firms constitute the sampling frame from which all potential treatment and control firms will be drawn by the CEM procedure. The average age of the newly public SMEs was 29.4 years at the time of IPO. This observation reflects a notable characteristic of Japanese IPOs: besides young, entrepreneurial companies, there tended to be more mature SMEs than in Anglo-Saxon countries (Sakawa & Watanabel, 2012). The maturity of sampled firms helps assure that there are plentiful pre-IPO observations for the CEM procedure and DD regression. In addition, more mature firms tend to face fewer financial constraints because they have fewer information asymmetries than younger firms (Fraser et al., 2015). Therefore, the presence of more mature SMEs in the sample will likely cause a downward bias in the estimated effects of IPOs and thereby yielding conservative interpretations for SMEs’ IPOs on their internationalization.

Variable Operationalization and Model Specification

To test H1, we created the variable New Subsidiaries to indicate how many new subsidiaries a focal SME established as the leading foreign shareholder in a certain period of time (Nadolska & Barkema, 2007; Vermeulen & Barkema, 2002). Since FDI projects may take more than 1 year to implement, we use a rolling 2-year window to count the number of new subsidiaries (Bavafa, Hitt, & Terwiesch, 2018; Bermiss & Greenbaum, 2016). This variable will reveal whether the pace of FDI accelerated after an IPO.

To test H2, we created two sets of dependent variables that reflect potential shifts in an SME’s propensity to invest in unfamiliar versus familiar locations after an IPO. First, since direct operating experience in a host country is essential to organizational learning in the internationalization process (Chang, 1995), the first set of dependent variables distinguishes host countries based on whether a firm had previously invested in them. New Subsidiaries (New Locales) is the number of new subsidiaries established by a focal firm in countries where it had not previously invested until the year of their establishment; New Subsidiaries (Existing Locales) is the number of new subsidiaries established in countries where the firm had previously invested. Like New Subsidiaries, these variables are measured over a 2-year rolling window.

The second set of dependent variables concerning H2 distinguishes host countries according to their regional classification. Prior research suggests that firms often show a propensity to expand within their home region as opposed to outside the home region due to their familiarity with the home region (Rugman & Verbeke, 2004), and this home-region orientation is particularly prominent among Japanese firms (Collinson & Rugman, 2008; Delios & Beamish, 2005). Using the World Bank classification,2 we classified host countries in the East Asia and Pacific region as being within the home region of Japan, and as outside the home region otherwise. New Subsidiaries (Non-Home Regions) is the number of new subsidiaries established by a focal firm in host countries outside the home region, and New Subsidiaries (Home Region) is the number of new subsidiaries established in any home-region countries. Again, these variables are measured over a 2-year rolling window. We expect that investment in both non-home and home regions is likely to increase in the post-IPO expansion wave. So is the investment in both new and existing host countries. However, our theory suggests that the increase in new host countries and in non-home regions will be more pronounced than that in existing host countries and within the home region.

We used a similar approach to create dependent variables involving SMEs’ ownership stakes in foreign subsidiaries to test H3. We employed two commonly used ownership thresholds to create two sets of dependent variables for testing. The first threshold is majority ownership (i.e., > 50%) (Li, Zhou, & Zajac, 2009; Makino & Beamish, 1998). We use a 2-year rolling window to count the number of majority- and minority-owned subsidiaries established by a focal firm as New Subsidiaries (Majority) and New Subsidiaries (Minority), respectively. We then increased the threshold to 80% as prior studies have classified subsidiaries with more than 80% foreign ownership as wholly owned subsidiaries according to the Financial Accounting Standards Board guidelines (Dhanaraj & Beamish, 2004; Gomes-Casseres, 1990), which represent greater commitment than IJVs. We applied the same operationalization and created two more dependent variables – New Subsidiaries (WOS) and New Subsidiaries (IJV). All of these variables are likely to increase following the IPO event; however, our theory posits that the effects of the IPO will be more pronounced on subsidiaries in which SMEs take either a majority stake or establish a wholly owned subsidiary.

Following prior studies (Pierce, Snow, & McAfee, 2015; Singh & Agrawal, 2011), our DD specification relates FDI decisions with the IPO event in the following way:

where \({Y}_{it}\) is one of the dependent variables for firm \(i\) in year \(t\), \({\updelta }_{i}\) are the firm fixed effects to account for unobserved organizational heterogeneity, \({\upgamma }_{t}\) are the year fixed effects to control for time-specific effects. The year of IPO was excluded to reduce temporal ambiguity. \({Post\_IPO}_{it}\), the main independent variable, is a dummy variable equal to one for the years after IPO for firm \(i\), if \(i\) was a newly public SME. As previously noted, IPO years in our sample are staggered from 1995 to 2009 and each panel of a treatment or control firm includes 5 years before and after the IPO year.

Coarsened Exact Matching (CEM)

We used coarsened exact matching, a nonparametric matching procedure, to reduce the asymmetry between the treatment and control groups, and thus mitigate potential selection bias (Iacus, King, & Porro, 2012). A distinct feature of CEM is that it requires the user to specify ex ante the bounds on the maximum imbalance on the matching covariates. This ex ante choice is the coarsening, and it enables the user to control the amount of imbalance in the matching solution. We chose CEM because it allows us to control the matching process with respect to firms’ state of internationalization at the time of IPO. Furthermore, since all potential control firms are private with which there is little publicly available financial information, it is less attractive to perform propensity score matching or other semiparametric matching procedures.

The CEM procedure proceeds as follows. We first chose a set of matching covariates (i.e., IPO Year, Industry Classification, Capital Stock, FDI Stock, and Pre-IPO FDI). The upper section of Table 1 presents the definitions of and data sources for these covariates. In addition to data availability, we considered two factors in selecting the covariates. First, the covariates must be closely related to FDI decisions because the matching procedure should ensure balance between treatment and control firms on factors pertinent to FDI decisions. Second, each additional matching covariate reduces the size of the matched sample. Therefore, there is a need to balance precision in the matching process and obtaining sufficient statistical power in succeeding analysis.

The treatment and control firms are exactly matched on IPO Year and Industry Classification, both of which are discrete variables. Capital Stock is the only available financial measure to proxy firm size because all firms in the control sample are private. FDI Stock and Pre-IPO FDI represent a firm’s level of internationalization and its momentum for FDI at the time of IPO, respectively. We created discrete bins for Capital Stock, FDI Stock, and Pre-IPO FDI to further identify the control firms. Specifying ex ante the bounds for the bins, i.e., coarsening, involves a trade-off between the stringency of the match and the proportion of treatment firms for which controls can be found. We chose the bounds according to the distributional characteristics of these covariates to ensure the balance between the treatment and control samples. The numbers of the bins for FDI Stock (n = 11) and Pre-IPO FDI (n = 6) are determined by the relatively small numbers of distinct values in these variables. We created 10 bins for Capital Stock with the bounds corresponding to deciles of the variable. We later tested the robustness of our findings using alternate bound specifications for this variable. Treatment firms without matching controls were dropped from the sample.

The CEM procedure found matches between 96 IPO firms and 555 control firms. The ratio between treatment and control firms is in line with prior studies using the same matching technique (Azoulay, Stuart, & Wang, 2014; Singh & Agrawal, 2011; Teodoridis et al., 2019). The lower section of Table 1 reports the summary statistics of matching covariates before and after CEM. The treatment and control firms in the post-CEM sample are significantly more balanced than the pre-CEM sample in all continuous matching covariates. The significant reduction in multivariate L1 distance further confirms improved balance after matching. The CEM algorithm can identify multiple controls that satisfy the matching criteria for a treatment firm and generate weights based on the similarity between the treatment and control firms. We retained multiple controls and their corresponding weights and applied them in subsequent univariate and multivariate DD analyses. We report host countries and the number of entries by firms in the post-CEM sample in Table 2.

RESULTS

Univariate Analysis

Table 3 reports the results of univariate analysis of the IPO effect using the pre- and post-IPO subsamples. There is no significant difference in any dependent variables except one between the treatment and control groups in the pre-IPO period (see “First difference (Pre-IPO)”), further confirming the effectiveness of CEM in identifying comparable treatment and control firms. These firms not only are balanced on matching covariates, but also exhibit similar FDI patterns in the pre-IPO period. By contrast, the differences between the treatment and control groups are much greater in the post-IPO period (see “First difference (Post-IPO)”). This result implies differences in foreign investment behaviors between the two groups in the post-IPO period are likely due to IPOs.

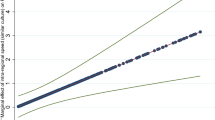

Meanwhile, the large differences between the pre- and post-IPO periods in the treatment group (see “First difference (Treatment group)”) suggest that newly public SMEs became significantly more active in FDI after the IPO; however, the differences, albeit of smaller magnitude, in the control group (see “First difference (Control group)”) imply that firms generally increased foreign investment over time even without an IPO. To use New Subsidiaries as an example, the post-IPO average of this variable in the treatment group (0.403) is greater than the group mean in the pre-IPO period (0.115), reflecting a difference of 0.289 or a 251% increase (= 0.289/0.115). However, there is also an increase in this variable in the control group (from 0.101 to 0.172, reflecting a difference of 0.071 or a 70% increase). The basic intuition of the DD approach is that the change in the control group represents the counterfactual that would have occurred to the treatment firms had they not undertaken IPOs and we can attribute the difference-in-differences, 0.218 or a 189% increase compared to the pre-IPO mean of the treatment group (= 0.218/0.115), to the IPO event. Figure 1 further illustrates the impact of IPOs by presenting the trend lines of New Subsidiaries of both the treatment and control groups. The diagram shows a significant, wave-like increase in the pace of FDI from the first year after IPO.

The univariate analysis of other dependent variables also consistently suggests a positive IPO effect (see “Difference-in-differences”). Moreover, the results indicate a post-IPO shift towards more investment in new host countries, majority-owned and wholly owned subsidiaries. However, a shift towards more investment in non-home regions versus the home region is not evident. To ascertain the link between IPO and FDI decisions more rigorously, we turn to the multivariate DD regression in the next section.

Multivariate Analysis

Our dependent variables are nonnegative count variables, so we turned to count data models for model estimation. Table 4 reports the results of a series of Poisson regressions using Eq. (1). The Poisson model is inappropriate when overdispersion is present in the count variable, however. We therefore performed several postestimation tests to examine the degree of overdispersion. First, the deviance and Pearson goodness-of-fit tests can be used as a test of overdispersion (McCullagh & Nelder, 1989). None of the deviance and Pearson statistics is significant in the reported specifications, suggesting that the Poisson model is appropriate. Furthermore, we implemented a formal test of overdispersion proposed by Cameron and Trivedi (2005: 670), where a positive test statistic indicates overdispersion. We found that none of the test statistics is positive in the reported specifications. Therefore, we concluded that the Poisson model is appropriate for our analysis.

H1 proposes that the pace of FDI by an SME will increase following its IPO. Consistent with the hypothesis, the coefficient for Post_IPO in Model 1 is positive and statistically significant (p = 0.000). To facilitate interpretation of results, Table 5 reports the average discrete changes (ADCs) for the effect of Post_IPO on each dependent variable. By exponentiating the coefficient estimates in Eq. (1), ADCs express marginal effects in terms of expected count. The ADC for Post_IPO on New Subsidiaries is 0.080 (p = 0.001), which suggests that on average newly public SMEs established 0.08 more subsidiaries in a rolling 2-year window in the post-IPO period than in the pre-IPO period. The magnitude of this difference is smaller than that of the difference-in-differences (0.218) reported in Table 3 – a predictable outcome when including various fixed effects in the regression. Yet, when compared to the pre-IPO mean of the treatment group in Table 3, this marginal effect still presents a 69% increase (= 0.080/0.115) in the pace of FDI from the pre- to the post-IPO period. Therefore, H1 is strongly supported.

H2 proposes that an SME’s foreign investments in unfamiliar locations will increase to a greater extent than that in familiar locations after the IPO. The coefficients for Post_IPO are positive and statistically significant in Models 2–5 in Table 4, suggesting an increase in investment in all location categories. However, it is inappropriate to test the equality of a variable’s effects across nonlinear models like Poisson by comparing coefficients. In this study, we adopted the method proposed by Mize, Doan, and Long (2019) to compare the marginal effects of IPOs across models and to test H2 and H3. This method uses seemingly unrelated estimation to combine estimates from two models, which allows for cross-model comparison of marginal effects. The results in Table 5 show that the ADC for Post_IPO is greater for New Subsidiaries (New Locales) than that for New Subsidiaries (Existing Locales). The cross-model difference (0.061, Model 2–Model 3) is statistically significant (p = 0.031), thus supporting H2. However, the cross-model difference in ADC between Models 4 and 5 is negative (− 0.044) with a p values just missing the 0.1 threshold. This indicates that newly public SMEs made more investments in the home region than outside the home region, but the difference is not statistically significant at conventional levels. One possible explanation for the lack of support for a higher tendency to invest in non-home regions is that a large quantity of managerial resources is required when firms venture outside the home region (Mohr et al., 2018). During a period of rapid foreign expansion, which tends to strain newly public SMEs’ limited pool of managerial talent, they may find it less costly to reallocate existing managerial resources within the home region or to acquire new knowledge and managerial talent with the home-region background than to search for managerial resources related to other regions. Overall, H2 is partially supported.

H3 suggests that the propensity for an SME to take a higher ownership stake in a new subsidiary will increase after the firm undertakes the IPO. Consistent with the hypothesis, the cross-model difference in ADC between Models 6 and 7 in Table 5 is positive and significant (0.072, p = 0.008). This indicates that although newly public SMEs increased investment in both ownership categories in the post-IPO period, the increase in the numbers of majority-owned subsidiaries was more pronounced than that of minority-owned subsidiaries. However, the difference in effects for wholly owned subsidiaries and JVs in Models 8 and 9 is not statistically significant, albeit the estimated difference is positive as expected (0.016, p = 0.541). This weaker result might stem from the fact that, compared to majority-owned subsidiaries, establishing wholly owned subsidiaries demands more managerial resources, and thus are less likely to be implemented. The result also may be explained by the potential interrelatedness between the location and ownership decisions.3 Despite the relaxed financial constraints, a significant shift towards more investment in less familiar locations as we find in H2 could limit newly public SMEs’ ability to realize a simultaneous shift from shared entry modes to wholly owned subsidiaries. It is also possible that due to untenable financial requirements these firms were forced to make smaller bets, so they did not pursue full ownership when making multiple foreign entries in close tandem.4 Overall, H3 is partially supported.

Supplementary Analyses

To explore the performance implications of post-IPO foreign expansion, in supplemental analyses we examined whether a wave of heightened FDI activities may influence newly public SMEs’ ability to generate revenues overseas using the data on “overseas/exports sales” provided by NEEDS. Although there is no further breakdown by types of foreign revenue, this variable nevertheless provides initial insights into a firm’s economic footprint overseas. The data are only available for some newly public SMEs in the post-IPO period and thus we are not able to match with SMEs that remained private, so the results can only be viewed as being suggestive. Table 6 shows that the ratio of foreign revenue to total revenue increased in SMEs 5 years after their IPOs and the paired t test confirms that the increase is statistically significant (p = 0.000). We further divided these firms into two groups by the mean of total foreign entries in 5 years after the IPO to examine whether the growth of foreign revenue relates to different levels of post-IPO international expansion. The two-way ANOVA test shows that the growth is marginally greater in more FDI-active SMEs than in less active ones (p = 0.066).

We also explored whether there is a correlation between post-IPO foreign expansion and investment in intangible resources, especially innovation, given the role of such intangibles in the SME internationalization process (Golovko & Valentini, 2011; Knight & Kim, 2009). Table 6 shows that the ratio of R&D expense to total revenue in SMEs increased significantly following the IPO (p = 0.040). Interestingly, more FDI-active SMEs appear to invest in R&D less aggressively than less FDI-active ones, though the difference is not statistically significant according to the ANOVA test (p = 0.140).

We performed a number of additional analyses to examine the robustness of our main findings.5 First, we examined whether the results are robust when we change the ex ante specified bounds of discrete bins in the CEM procedure. The numbers of the bins for FDI Stock and Pre-IPO FDI are largely determined by the small numbers of distinct values in these variables, so they are not amenable to further refining. The specification for bounds is more flexible for Capital Stock (currently ten bins). In robustness checks we employed less coarsened (15 bins) and more coarsened (5 bins) matching criteria. Changing the bound specification resulted in changes in the size of the treatment and control groups and the balance between the two groups. Despite these changes, the estimation results using the re-matched samples are consistent with the main findings. Second, we re-estimated the models using alternative post-IPO windows of 2, 3, and 4 years. The results are qualitatively the same as the main results that used a 5-year window. Third, the results remain largely consistent when we included the year of IPO in the post-IPO window. Furthermore, instead of a 2-year rolling window, we used a 3-year window and no rolling window to re-construct the dependent variables. Results based on these alternative measures are largely consistent with the main findings.

We also explored whether the results vary depending on the sectoral classification of new subsidiaries. Most subsidiaries in our sample are classified as manufacturing entities (50.1%), followed by wholesale entities (39.3%). Other subsidiaries were miscellaneous service units. We focused on the two leading categories and re-estimated the models using new dependent variables based on manufacturing and wholesale subsidiaries separately. The results regarding the pace of internationalization remain significant for the two types of overseas entities. However, the effects on the shifts in the location and ownership patterns are weaker for manufacturing investments. One explanation for this difference is that manufacturing operations tend to be more complex than wholesale activities, and thus require more managerial, technological, and human resources besides the necessary capital input. These managerial resources are apt to be slower to develop than the financial resources after the IPO. Despite the improved capital availability, newly public SMEs may still not be able to immediately bridge the knowledge and human resource gaps to support aggressive expansion of manufacturing activities into unfamiliar locations or to effectively exercise hierarchical control of these activities along with the administrative and other changes brought upon by going public.

DISCUSSION

This study contributes to several strands of literature. First, it provides corroborating evidence that internationalization can proceed in a wave-like pattern as the Casino model suggests, and it identifies the IPO as a significant antecedent to the wave-like pattern (Håkanson & Kappen, 2017). We find that despite the presumed lack of managerial resources at small firms (Buckley, 1989; Coviello & McAuley, 1999), newly public SMEs in our sample not only accelerated the pace of foreign expansion in the years immediately following the IPO, but also increasingly expanded into new host countries and took majority ownership stakes in new subsidiaries at the same time. We maintain that the Uppsala model does not adequately explain these concurrent shifts in investment behaviors around the IPO because such shifts are not congruent with the continuous, gradual process of learning and network-building that underpins the incremental pattern central to this theory (Vahlne & Johanson, 2017). By contrast, our empirical observations are consistent with the main premise of the Casino model, which suggests that firms primarily aim to utilize available financial and other resources through concurrent entries. Furthermore, we examined how the IPO event affects the pace, direction, and commitment of foreign investment by SMEs. We argue that such an analytical approach not only provides a more comprehensive assessment of the association between IPOs and SME international strategy, but also builds upon and extends the Casino model to formulate new theoretical predictions concerning the location and ownership patterns in the internationalization process.

We did not find a greater tendency to enter countries in non-home regions than the home region or a higher propensity to establish wholly owned subsidiaries than joint ventures by newly pubic SMEs. These nuanced results reflect an interesting characteristic of the immediate period after an SME’s IPO: while improved capital availability enables more aggressive choices for international expansion, the development of general internationalization capabilities is likely still in flux. It might be that this dynamic between the material and managerial resources have led to more risk-taking investment decisions by newly public SMEs, but in a pattern partially grounded in their existing knowledge base.6 Overall, our findings are consistent with both the Casino and the Uppsala models with regards to particular aspects of the internationalization process in the destabilizing period after the IPO. Therefore, rather than subsuming seemingly divergent observations under a single paradigm – whether the Uppsala model or the Casino model – future research should recognize these alternative logics and patterns of internationalization processes and focus on organizational and environmental conditions conducive to different patterns to increase our understanding of the pace, direction, and commitment of the SME internationalization process.

We suggest that research in this direction may benefit from embracing a Penrosean lens more explicitly (Tan et al., 2020). Both the Uppsala and the Casino models drew on Penrose’s (1959) theory of the growth of the firm. In particular, the Casino model’s central idea that management utilizes available resources to seek opportunities on a broad international front is aligned with the Penrosean view that excess resources not only enable but motivate firm growth when management discovers or creates new markets to make the best use of resources available in the continuous pursuit of long-run profits and growth. Therefore, some of Penrose’s key ideas can figure more prominently into the analysis of firms’ internationalization decisions (Kor & Mahoney, 2000). For instance, one natural extension of the current study is to examine investment decisions by public SMEs after the initial post-IPO wave to determine the extent to which the decisions further out in the future are rooted in previous experiences and how they potentially differ from those made during the post-IPO wave. A related research question is whether the impact of financial resources varies across different stages of an SME’s life cycle as the firm grows larger. Future research could also devise an explicit measure of managerial resources to test their effects on post-IPO FDI and further explore the interplay between financial and managerial resources in the SME internationalization process.

Second, our findings begin to shed light on the under-identified financial drivers of SME international strategy. Although SMEs are known to have limited access to capital, financial factors are an often-overlooked determinant of SMEs’ investment decisions, as most prior research has focused on SMEs’ ownership advantages derived from intangible assets (Dabić et al., 2020; Knight & Kim, 2009; Oehme & Bort, 2015). However, corporate financing choices, including IPOs, can help SMEs reduce their financial disadvantages and even turn the high availability of capital into a finance-specific ownership advantage (Oxelheim, Randøy, & Stonehill, 2001). Therefore, our study complements the extant literature and helps develop a more comprehensive perspective on the necessary conditions for SME internationalization. In addition, because corporate financing events tend to occur in waves (Dittmar & Dittmar, 2008) and are subject to the influence of business cycles (Helwege & Liang, 2004), we believe it will be particularly valuable to explore in future research the temporal connections between different financing events and the wave-like patterns of the internationalization process. In the context of IPO firms, it would be valuable to consider firms’ secondary offerings, cross-listings, and other means of raising capital in the years after going public. Such research could determine whether financial and other resources enable SMEs to continue their internationalization processes, as well as how the pace, direction, and commitment levels change in the years after IPOs.

Third, this study contributes to the IPO literature by implementing an identification strategy to isolate the effect of IPOs on internationalization of SMEs. Our analysis directly addresses repeated calls by IPO and IB researchers for systematic study of the impact of IPOs on internationalization (Certo et al., 2009; Engelen et al., 2020). By comparing the differences in FDI decisions between pre- and post-IPO periods, our study confirms a theoretical link between these two major developments in an SME’s life cycle. Moreover, our post hoc analysis indicates that SMEs may have invested less in R&D when they engaged in heightened international expansion after the IPO. In other words, even though ownership advantages rooted in intangibles generally support foreign direct investment, there may be a substitutive relationship for a time between different forms of corporate development. Some noted that government assistance programs, such as long-term loans and shorter-term trade credit that support SME exports may create skewed incentives for smaller firms to pursue international expansion and divert limited managerial resources away from innovation, thereby eroding SMEs’ competitive advantages in the long run (Acs, Morck, & Yeung, 2001). By the same token, although accelerated FDI enabled by equity financing may help the SMEs increase foreign revenue, it could potentially cause misallocation of valuable resources that are crucial to these firms’ innovativeness. Thus, an integrative analysis of the post-IPO dynamics between international expansion and other forms of corporate development and their joint effects on SMEs’ long-term innovative and financial performance could add useful insights to the IPO literature.