Abstract

Central bank responses to COVID-19 have been extraordinary in speed, in size and in scope. Much easier monetary policy, massive liquidity provision, and targeted credit support to the real economy all played a role in stabilizing financial conditions and credit. On net, there is preliminary evidence that central bank actions have been a positive—for access to credit and for the real economy—during very trying times. But the first six months have made clear that central bank policy can only indirectly address the core economic policy challenges of the crisis, whose trajectory remains highly uncertain. The risks to the economy and financial system remain very large, and key policy questions—on the degree of fiscal policy support to the real economy, about the limits of central bank risk taking and monetization of debt, and about the wisdom of heavy reliance on central bank policies given their impact on leverage and debt levels—remain just that.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Central bank responses to COVID-19 have been extraordinary in speed, in size and in scope. The Federal Reserve announced as many emergency programs in eight days (March 14 to 23, 2020) as it did during all of 2008. Moreover, the Fed implemented more programs in 4 months than in the entire global financial crisis. On net, there is evidence that central bank actions have been a positive – for access to credit and for the real economy—during very trying times. But this early conclusion has two caveats: first, in a pandemic a central bank’s role is limited. At best it can cushion the blow via lending and easier financial conditions, and so provide a bridge to future economic recovery. But encouraging more leverage is a double-edge sword, since it can increase future fragility. Second, it is frankly too soon to make a serious judgment on the ultimate effectiveness of any particular set of economic policies—central bank or otherwise.

The size and speed of the response by the Fed and other central banks mirror the size and speed of the COVID-19 crisis. Typically, economic crises of this scale are preceded by financial crises. The 2007–2009 global financial crisis is a classic example; it started with a financial panic, which accelerated in spite of large central bank and fiscal interventions. The financial deterioration (panic) happened rapidly, but only over time did it drag the real economy down with it.

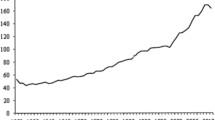

This time exactly the opposite happened. The public health restrictions required to manage the pandemic caused enormous, instantaneous (and largely) negative shocks to both aggregate supply and demand. The real economy figuratively stepped off a cliff in March 2020 (see Fig. 1), prompting similarly large and swift policy actions by monetary and fiscal authorities. The huge sectoral differences in the impact of the crisis—shutdowns in many retail services, travel, entertainment, and hospitality, as well as non-Covid, non-emergency health care—led to a sharp drop in overall economic activity, and the prospect of massive unemployment and business failures. The unusual combination of supply and demand shocks will likely have long-term implications for the structure of the economy and growth, and they will remain a challenge for economic policy, including central banks. See Guerrieri et al. (2020).

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of New York. See Lewis et al. (2020)

Weekly Economic Index

Importantly, the financial system was quite strong at the beginning of the COVID crisis, reflecting the relatively long global (and U.S.) economic expansion as well as much more robust capital and liquidity buffers in the financial system, particularly at the largest global banks. See Borio (2020). Indeed, one of the aims of central bank (and fiscal) policies since March 2020 has been to provide enough support to the real economy to prevent a large negative feedback loop from real economy bankruptcies and defaults to the financial sector. If the collapse of the real economy causes a subsequent financial crisis, then the United States and world face an even more dire outlook: the collapse of credit formation and liquidity provision by banks and other financial companies, which in turn would cause an even further step down in the economy, employment and well-being.

1 Central bank policy

In response to the economic collapse, central banks, including the Fed, launched a massive set of programs to address both the real and financial distress caused by the pandemic. See Fleming et al. (2020). Like the fiscal policy responses, many of the new (or renewed) central bank programs were intended as “cushion the blow” policies to sustain credit formation, support the real economic activity by easing financial conditions, provide liquidity and reduce financial distress.Footnote 1

Central bank policy actions and programs can be roughly broken into three categories: monetary policy, liquidity provision/lender-of-last-resort to the financial system, and targeted credit programs directed to support nonfinancial sector players: firms, households, municipalities. Importantly, these actions were accompanied by enormous regulatory relief actions, including relaxation of capital and liquidity standards, and loosening of market regulations and activity restrictions in the financial sector, again with the aim to make financing more available at lower cost.Footnote 2

1.1 Monetary policy

Easing monetary policy in face of a recession is standard operating procedure. Nearly every central bank on the planet has sharply cut policy interest rates (where they could do so).Footnote 3 In many advanced economies, including the United States policy rates were set to their effective lower bound, and ‘unconventional’ policies such as asset purchase programs were started or expanded.Footnote 4 Moreover, a number of emerging market central banks not only cut rates but began asset purchase programs (both government and private sector), some doing so for the first time.Footnote 5 One notable exception is that central banks with negative policy rates did not cut their rates further.Footnote 6

In the case of the Fed, the initial announced size of “QE” asset purchases was immediately and dramatically upsized in reaction to severe dislocations in fixed income and funding markets. On March 15, the FOMC announced asset purchases of $700 billion “over the coming months”, amounts that were somewhat larger than the overall pace of purchases during QE1 and QE2. (FOMC 2020a).Footnote 7

Prior to the March 15 announcement U.S. Treasury markets were in severe turmoil, with extreme volatility, widening spreads, and a sharp drop in liquidity. In response, the New York Fed’s open market desk bought almost $40 billion of U.S. Treasuries in a single day, March 13. By the following Thursday, March 19, the desk was purchasing $75 billion of Treasuries per day: a pace that was maintained until April 1.Footnote 8 The FOMC officially announced this “whatever size is needed” policy on March 23. (FOMC 2020b).Footnote 9 To give a sense of the extraordinary scale, the desk purchased more U.S. Treasury securities (more than $800 billion) in the 15 working days between March 12 and April 1 than during the entire 2 + years of QE3.

The rationale for the desk becoming “dealer of last resort” is straightforward. Large-scale asset purchase programs are intended to lower term premia and risk premia through portfolio rebalance incentives. But severe turmoil in benchmark Treasury markets pushed in the opposite direction; long-term Treasury yields initially rose, pushing up other long-term interest rates up with them. (See Fig. 2). The typical crisis flight to quality which lowers Treasury yields was more than offset by a flight to liquidity, with widespread selling of Treasuries by leveraged investors for margin calls, by mutual funds to fund record redemptions, and by countries to provide dollar funding to their economies or manage their exchange rates. Massive buying and selling overwhelmed the infrastructure of the market, volatility spiked and market liquidity (ability to trade) evaporated (Fig. 3). See Fleming (2020) and Duffie (2020) for a more complete discussion. There was an immediate spillover to credit markets. The corporate bond market—typically the more liquid investment grade corporate market –was particularly impaired in part because of mutual fund flows. See Gilchrist et al. (2020), Liang (2020), and Ma et al. (

2 Conclusion

To a surprising degree financial markets and lenders were able to look beyond the economic cliff during the first few months of the COVID crisis, due in part to very large and swift policy actions by central banks. Much easier monetary policy, massive liquidity provision, and direct credit support to the real economy all played a role in stabilizing financial conditions and credit. Initial central bank policy responses—providing liquidity and exceptionally large asset purchases—stabilized financial conditions quickly in March and April, while announcements of upcoming targeted credit programs for the real economy by both fiscal and monetary authorities gave investors and lenders the confidence to lend at reasonable, rather than astronomical interest rates.

But central bank policy can only indirectly address the core economic policy challenges of the crisis, which is ongoing, and whose trajectory remains highly uncertain. While central bank policy can continue to play its role, the first six months of the crisis has made it clear that it cannot (or rather should not) do so alone. And, so, the risks to the economy and financial system remain very large. In the near-term there is uncertainty about the willingness and ability of fiscal authorities to support incomes and economic activity, about the limits on central bank lending and risk taking, and about the efficacy of overreliance on central bank policies given the impact on leverage and debt levels. The longer term challenges are equally large: restarting economic growth, deleveraging the economy and managing what are likely to be large structural changes coming out the pandemic.