Abstract

Learning to play an instrument at an advanced age may help to counteract or slow down age-related cognitive decline. However, studies investigating the neural underpinnings of these effects are still scarce. One way to investigate the effects of brain plasticity is using resting-state functional connectivity (FC). The current study compared the effects of learning to play the piano (PP) against participating in music listening/musical culture (MC) lessons on FC in 109 healthy older adults. Participants underwent resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging at three time points: at baseline, and after 6 and 12 months of interventions. Analyses revealed piano training-specific FC changes after 12 months of training. These include FC increase between right Heschl’s gyrus (HG), and other right dorsal auditory stream regions. In addition, PP showed an increased anticorrelation between right HG and dorsal posterior cingulate cortex and FC increase between the right motor hand area and a bilateral network of predominantly motor-related brain regions, which positively correlated with fine motor dexterity improvements. We suggest to interpret those results as increased network efficiency for auditory-motor integration. The fact that functional neuroplasticity can be induced by piano training in healthy older adults opens new pathways to countervail age related decline.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Making music is a multimodal task that requires not only auditory-sensory-motor integration and emotional processing, but also higher order cognitive functions1,2. These cognitive functions, which include processing speed, attention, executive functioning, as well as working memory are all known to naturally decline with age3.

Therefore, to fully grasp brain processes underlying the production of music and its potential effects on aging, it is important to study the interaction between the different brain areas involved in these processes. One way to quantify these interactions is using functional connectivity (FC) by calculating and comparing the temporal correlation between different parts of the brain. FC can be measured using resting-state functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (rs-fMRI). Brain regions that are functionally related, share similar spontaneous low-frequency fluctuations during rest4. This way, distinct functionally connected neural networks have been identified in the human brain, such as primary processing networks, which include the sensorimotor network (SMN), and the auditory network (AN), but also higher-order networks, like the executive control network (ECN, involved in goal-directed behavior, attention and working memory) and the default mode network (DMN)5. The DMN is unique as it shows a high level of activity at rest, but lower levels of activity when performing a task6. Most interestingly, it is the most consistently found network to be affected by aging (for reviews see e.g. ref.5,7). Another higher-order network that has been associated with non-pathological cognitive ageing in a large scale study is the cingulo-opercular network (CON), involved in cognitive control and goal-directed behaviour8. Often the CON network is also referenced as the salience network. For other networks, especially the primary processing networks, findings are more diverse. However, most studies find decreases in the AN and no change or decreases in the SMN in older adults5.

When investigating the effects of playing an instrument, typically musicians and non-musicians are compared. Here, the most consistent finding among studies is a higher FC between auditory and motor regions in musicians9,10,11,12,13. Interestingly, the largest study to date14 found increased FC within the AN and between bilateral superior and middle temporal, inferior frontal, and inferior parietal regions, but not between auditory and motor regions in musicians compared to non-musicians. Thus, results are still too inconsistent to draw clear conclusions about the exact effects of musical training on functional brain plasticity. One main problem is that most studies used relatively small sample sizes, which not only leads to a reduced chance of finding a true effect but also increases the probability that significant results do not reflect a true effect15.

Few studies investigated the effect of musical training on FC in longitudinal settings and those who did also used relatively small sample sizes. One study16 investigated eight weeks of drum training in a group of 15 young (16–19 years old) participants compared to a passive control group and identified a significant increase in FC between auditory and motor regions as well as between auditory and parietal regions in the drum group but not in the control group over time. Another study conducted over 24 weeks of piano training found increased FC within the SMN and between auditory-motor regions in 29 young adults compared to a passive control group17. However, these effects receded after 12 weeks of no training17. While these studies used younger populations to study the effect of musical practice, learning to play an instrument has also become a target intervention to slow down or counteract age-related cognitive decline in recent years18,19,20. Although these studies show promising results, they lack statistical power (between 8 and 16 participants in the intervention groups) and they did not use neuroimaging methods to investigate the underlying neural adaptions induced by the training.

Yet, important factors in the aging process of the human brain are maladaptive changes of its FC, most often resulting in reduced cognitive performance5. These include reduced FC within and between networks, but also increased FC, which is usually interpreted as a compensatory mechanism21,22,23,24,25. Based on the above-mentioned studies, musical training might be a promising tool to promote successful aging, potentially altering connectivity between brain areas, which in consequence may lead to preservation or even improvement of cognitive abilities26. Especially since Rogenmoser et al.27 have suggested, based on structural data, that music as a leisure activity can have an age-decelerating effect on the brain.

A recent publication by our consortium28 investigated the effect of six months of piano practice (PP) on white matter structural connectivity in healthy older adults as part of a larger randomized controlled trial (RCT). Analyses revealed a stabilizing effect of PP on microstructure of the fornix (a main output tract of the hippocampus), but no significant (Bonferroni-corrected) effects in auditory and motor-related tracts. However, PP participants still advanced in their playing abilities. While these improvements could not be explained by structural connectivity changes, here we investigate whether FC changes may underlie these improvements, using the same study sample. In addition, we are interested in whether piano training also influences FC of the DMN, which is known to be affected by aging and other primary processing networks, where the exact impact of ageing is still unknown5. The current study aims to investigate FC changes after 6 and 12 months of PP compared to an active control group participating in music listening/musical culture (MC) lessons in a large older adults’ sample. Specifically, we use seed-to-whole-brain FC analysis with the following 8 seeds that have been implicated in previous studies on musical expertise and aging: Heschl’s gyrus (HG, belonging to the AN)29, motor hand area (M1H, belonging to the SMN)30, hippocampal formation (HPF, belonging to the DMN)31, and inferior frontal gyrus (IFG, belonging to the ECN)32.

The HG is affected by musicians’ status in a large number of studies33,34,35,36,37,38, with changes being related to music proficiency33,34. The HG, as part of the auditory cortex, is anatomically linked to the primary motor cortex and the IFG via the arcuate fasciculus39. The IFG has been shown to be involved in music processing40,41 and the generation and selection of motor sequences42. Due to its involvement in working memory processes43 the IFG represents an interesting seed region. Improvements in working memory have been shown after six months of piano training in healthy older adults18,20, although working memory is particularly affected by age3. As playing the piano specifically engages fine motor control of hands and fingers, we selected a seed located at the M1H44. In an earlier publication of this study we showed that in comparison with the MC group, first, practicing piano resulted in greater improvements in manual dexterity and second, that unimanual dexterity and grey matter volume of the contralateral M1 changed together during the second semester of training45. Further, fine motor control is known to deteriorate with advanced age46,47. Another region of interest is the HPF, not only because of its involvement in aging and cognitive decline48, but also because of its involvement with music-evoked emotions49 and higher-order pitch processing50,51,52.

Each seed was investigated separately for the left and right hemispheres. We hypothesize that learning to play the piano primarily leads to FC increase between auditory and motor regions as found in previous studies9,10,11,12,13,16,17, verifying the association of those FC changes with behavioural measures and piano practice progress, closely linked to piano training, so-called near-transfer, primarily expressed in auditory and motor tasks. In addition, we hypothesize that learning to play the piano has the potential to counteract or slow down age-related FC changes, including increased FC in and between the SMN and AN. Considering the limited literature on the effects of musical instrument playing on the ageing DMN and ECN, we included these networks for exploratory analyses, hypothesizing that PP could have a beneficial effect counteracting age-related changes in these networks.

Materials and methods

The study was reviewed and approved by the ethics committee of Hannover Medical School as well as the cantonal ethics committee Geneva. All participants gave written informed consent before participation and all experiments were compliant with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Participants and study design

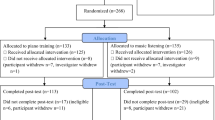

A total of 155 subjects (62–78, mean age = 69.7 years, 92 females) were recruited for the current RCT in Hannover (Germany, 92 participants) and Geneva (Switzerland, 63 participants). Participants had to be in good overall health, right handed53, retired, and non-reliant on hearing-aids. Furthermore, included participants should not have received more than 6 months of formal musical training outside the school curriculum during their lifetime. The general sophistication scale of the Goldsmiths Musical Sophistication Index (Gold-MSI) was assessed to measure their musical sophistication at baseline (minimum/maximum achievable score = 18/128)54. The cognitive telephone screening instrument (COGTEL)55,56 was used to assess cognitive functioning and avoid the inclusion of participants with early-stage dementia. As this test was specifically developed for older adults, it provides a global measure of cognition, based on several memory and executive function subtests. A cut-off value of below 10 was set a priori based on the original publications55,56, however each participant in the current study reached a score of at least 15. The participants were randomly assigned to one of the two intervention groups: PP or MC. In order to obtain homogeneous groups, age, gender, education level, and COGTEL score were taken into account to achieve equal distributions of these factors across both groups. Participants only learned of their group assignment after baseline testing. Both groups received one 60 min lesson per week for one year and were instructed to do homework daily for at least 30 min. PP lessons were taught in dyads whereas MC lessons took place with 4–6 participants. The lessons were designed and regularly supervised by two music pedagogy professors. Twenty-four teachers were involved who all were professional musicians with at least a bachelor’s degree. Participants in the PP group learned to play the piano with both hands (separately at first), how to read a musical score, and played different styles of music. MC lessons focused on active and analytical listening to music of different epochs and genres, learning about music history and musical styles, and information on basic formal and structural properties. The course aimed to create general enjoyment and appreciation of music, however, it excluded any active music-making (e.g. singing), or other music-related movements (e.g. clap**). More details about the study design can be found in James et al.57 and in the supplementary material of Worschech et al.58. To monitor the participants’ adherence to the study protocol, daily homework logs were collected. Adherence was based on self-report from the participants on how much they practiced daily at home, which had to be put into a training diary and collected regularly. Participation was assessed by the teachers after 6 and 12 months. In addition, the teachers followed the participants’ progress to make sure they did indeed practice at home. We observed a solid adherence to the interventions in all participants.

Participants underwent testing before the start of the interventions (T0), after 6 months of lessons (T1), and after 12 months of lessons (T2). Due to the COVID-19 outbreak and local restrictions, there were delays in testing at T2 for the majority of participants. Although some participants had to finish their courses online, all included participants had at least 46 lessons when T2 testing took place. To factor in the delays in testing, all statistical models include the time between measurements as a covariate.

Of the 155 participants, 120 completed MRI scanning at all 3 time points. Of these, 4 had to be excluded from the analyses because of artefacts in the T1 image, one participant was excluded because of too much atrophy and myelin degeneration, 6 participants showed excessive head movement and had less than 150 of 460 remaining volumes in the functional scan after head-motion scrubbing. This resulted in a total of 109 participants who were included in the final analyses (53 in the MC group and 56 in the PP group).

Image acquisition

MR images were acquired on 3.0 T Siemens MRI scanners (Hannover: Magnetom Skyra, Geneva: Magnetom Tim Trio; Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) using 32-channel head coils. Both study sites used the same scanning parameters. For the resting-state fMRI images, the following echo planar imaging (EPI) sequence was used: voxel size = 2.5 mm isotropic, FoV = 210 × 210 × 135 mm3, multiband acceleration factor = 3, repetition time (TR) = 1350 ms, echo time (TE) = 31.6 ms, and 460 volumes. The scan lasted 10.31 min and participants were instructed to focus on a fixation cross in the middle of the screen during scanning. Additionally, a high-resolution T1-weighted structural image was acquired, using the following MP2RAGE sequence59: voxel size = 1 mm isotropic, FoV = 256 × 240 × 176 mm3, TR = 5000 ms, TE = 2.98 ms, flip-angle 1 = 4°, flip-angle 2 = 5°, and 176 slices. To account for potential site effects and different MRI scanners, this factor was included as a covariate of no interest in all statistical analyses. For noise reduction during scanning, subjects wore Comply™ Canal Tips with an average noise reduction of 29 dB.

Preprocessing

The data was analyzed using the Data Processing Assistant for Resting-State Toolbox (DPARSFA, http://rfmri.org/DPARSF)60 and SPM12 (Wellcome Trust Centre for Neuroimaging, London, England). Preprocessing followed the recommended standard DPARSFA protocol.

In a first step, the first five image volumes of the functional images were discarded to account for initial signal instability. The remaining images were then slice-timing corrected and realigned to a mean image. Voxel-specific head motion parameters were calculated. Then structural images were co-registered to the functional images and segmented into white matter (WM), grey matter (GM), and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) maps using DARTEL61. The Friston 24-parameter model62 was used to regress out motion artefacts from the realigned images. In addition, WM, CSF, and global signal were regressed out. Images were then normalized to MNI space using DARTEL and temporally bandpass filtered (0.01–0.10 Hz). In the next step, head motion scrubbing was performed, which removed time points with a framewise displacement of more than 0.4 mm63. In the last step, images were smoothed with a Gaussian kernel of 7 mm3 (full width at half maximum).

Seed-based functional connectivity analysis

Calculation of FC was carried out with a seed-based approach, using the DPARSFA toolbox60. Here, the time course of each seed (i.e. the averaged time courses of all voxels within this region) was correlated pairwise with the time course of all other voxels within the brains’ GM (Pearson’s correlations). Then individual’s correlation (r) values were normalized by means of Fisher’s z transformation and evaluated using an SPM second level model. Difference images for T1-T0 and T2-T0 were calculated and entered into a General Linear Model to assess changes after 6 and 12 months respectively. Anatomical locations of the significant clusters were identified using the Automated anatomical labelling atlas (AAL3)64.

Seed regions

As outlined in the introduction, eight different seeds were selected based on a recent study by our consortium28, their relevance in music making/musical processing, aging brain literature, and their susceptibility to training-induced changes.

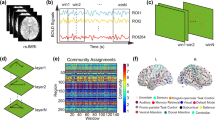

Peak coordinates for the seeds were selected based on existing literature and a mask for each seed was created using a 5 mm radius around the peak coordinates. Table 1 summarizes the selected seeds, their peak MNI coordinates and the reference the coordinates are based on. Locations of the selected seeds are visualized in Fig. 1.

Behavioral tests

As this analysis is focusing on resting-state FC, only tests that are relevant for the statistically significant FC changes are explained in detail below. As explicated in the hypothesis, the focus of this analysis is on the acquisition of a motor skill. Thus, for the evaluation of near transfer effects of the acquisition only motor tasks were evaluated. For a full list of administered tests in the study, please refer to James et al.57.

MIDI-based scale analysis

An adaption of the MIDI-based scale analysis (MSA)66 was used in both groups to measure improvements in piano playing. This measure has previously been shown to be an indicator of pianistic expertise67. Participants were instructed to play sequences of 15 five-tone range scales (C-G) in both playing directions with the right hand, using the following fingering: 1-2-3-4-5-4-3-2-1-2-3-4-5-4-3-2-1 (1 = thumb, 5 = little finger). The outcome measure was the mean standard deviation of the time between the onsets of two subsequent notes (IOI = inter-onset interval). The desired IOI was set to 790 ms and paced by a metronome.

As we considered this task too difficult and thus frustrating to perform with the left hand for the MC group at T1 and T2, this test was performed with the right hand only.

Purdue pegboard

The Purdue Pegboard Test (PT)68 was used to measure fine motor dexterity and gross movements of the hands, fingers and arms. The PT consists of three sub tests that all measure gross hand and arm control: right hand (PT-RH), left hand (PT-LH), and both hands (PT-BH, also measuring bimanual coordination). These tests take 30 s each and consist of placing as many pins as possible in a vertical row with the specified hand (PT-RH and PT-LH) or both hands at the same time (PT-BH).

Moreover, there is another assembly subtest measuring fine finger/ fingertip dexterity and bimanual coordination (PT-A). In this test, participants have 60 s to assemble a small tower consisting of a pin, a washer, a collar, and another washer. Final scores consist of the total number of pins placed/objects assembled within the given time.

Statistical analysis

Group-level

In a first step, only baseline measurements were taken into account to assess whether the two groups differed in FC before the start of the interventions. Group differences at baseline were assessed with two-sample t tests entered into separate General Linear Models (GLM) for the eight seeds of interest in SPM12, including site, age at the start of the intervention (demeaned), and gender as nuisance covariates.

In a next step, to assess training-related changes, difference images were calculated between T0 and T1 as well as T0 and T2 and also entered into a GLM, with site, age at the start of the intervention (demeaned), gender, and time between scans (demeaned) as nuisance covariates. Separate GLMs were created for each seed for six and twelve months’ data. To measure FC changes over time, one-sample t tests including the full sample (both groups combined) were calculated (PP+ + MC+ for increased FC over time and PP– + MC– for decreased FC over time).

Group differences (over time) between the two intervention groups were assessed with a two-sample t test (MC > PP and PP > MC). To account for the amount of voxels in the whole brain analysis, we used FWE correction at cluster level, and lowered the significance threshold further, to account for the eight seed regions, resulting in a significance threshold for each seed region of pFWE < 0.05/8 = 0.00625.

In a last step, it was important to know whether the seeds and cluster regions were positively or negatively correlated (i.e. anticorrelated) at baseline to distinguish between different FC changes over time. A FC increase over time could for example mean a higher positive correlation or a decreased anticorrelation. For this purpose, we created binary masks from the significant clusters and used these to extract the baseline correlations from the T0 images for the respective seed regions.

Further statistical analyses were performed in IBM SPSS Statistics version 27 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). As difference images were entered into the GLMs, significant effects do not quantify where this difference originates from. Therefore, the mean value over the significant cluster was extracted and compared against 0 for each group using a one-sample t test. A non-significant test result implicated no change over time for this group, while a significantly higher mean would quantify an FC increase and a lower mean a significant FC decrease over time. Due to the number of tests (12 in total), Bonferroni correction was used, setting p < 0.0042 as the significance threshold.

Behavioral and correlational analyses

To keep in line with the FC analysis, we performed separate analyses for 6 and 12 months data. Hence, MSA was analyzed using two 2 × 2 (Group × Time) mixed-design ANOVAs, with group as a between-subject variable and time as a within-subject variable. Outliers with more than two SD from the mean were excluded from this analysis. This was the case for four participants. Eight additional participants with at least one missing value were excluded. Therefore, the final analysis on MSA comprised 45 MC and 52 PP participants. PT was analyzed separately for the four sub-tests, each with a 2 × 2 (Group × Time) mixed-design ANOVA. For correlation analyses, difference scores were calculated and correlated with extracted cluster FC changes (T1–T0, or T2–T0, depending on the outcome of the FC analysis). Correlations were only calculated if post-hoc analyses on FC revealed a significant FC change over time.

In total eight correlations were computed, therefore, the significance threshold was set to p < 0.00625.

Results

Demographic data (N = 109)

Both groups did not differ in respect to age, gender, education level, COGTEL score and Gold-MSI score (Table 2).

FC group differences at baseline

No significant group differences were detected at baseline.

FC results—6 months

There were no significant effects after 6 months of training.

FC results—12 months (T2)

No significant effects were found for the left HG, left M1H, right HPF, and left IFG seeds. The right IFG was the only seed region that showed a main effect of time. Across all participants, there was a significantly higher FC (pFWE = 0.002, k (number of voxels in the significant cluster) = 310, T = 4.46) between the right IFG and the left angular gyrus after twelve months of interventions. For that seed, no significant effect of group could be detected. The right HG, right M1H and left HPF all revealed significant FC group differences over time. The only FC seed which showed a significant MC > PP effect of group after 12 months was the right HG. These significant group results are described in more detail below.

A summary of all significant effects after 12 months of interventions are shown in Table 3. Additionally, results for the PP group after 12 months are displayed in Fig. 2.

Results for the PP group after 12 months of intervention. Significant FC increases or decreases that were found for the PP group in comparison to the MC group. Gray edges indicate increased FC and red edges indicate reduced FC between regions after piano training. Seed regions are printed in bold. Blue nodes = results for HG (Heschl’s gyrus), green node = results for HPF (Hippocampal formation), Black nodes = results for M1H (Motor hand area). IPL inferior parietal lobule, dPCC dorsal posterior cingulate cortex, dPMC dorsal premotor cortex, PCG precentral gyrus, SPL superior parietal lobule, R right, L left. Images are displayed in radiological convention (left = right hemisphere, right = left hemisphere). The results were visualized with BrainNet viewer104, thus the current findings might not be generalizable to the global population. This poses an interesting and relevant research gap that should be explored specifically in future research.

In conclusion, the current study demonstrated piano training-induced FC changes in specific sensorimotor and auditory-motor networks in healthy older adults after 12 months of training. Although evidence for the positive effect of learning to play the piano to counteract or slow down age-related decline is limited in the current study, the fact that the older adult brain shows neuroplastic adaption to a newly learned skill raises hope that it is possible to actively influence the course of neurological aging, potentially by increasing cognitive reserve. Therefore, future studies are needed to see whether learning to play the piano at an advanced age might be an effective tool to reduce the burdens related to age-related cognitive decline and sensorimotor deterioration in the long term. That music practice might be effective is plausible, as musical activities involve several functions and skills that are prone to decline with age, such as working memory, attention, processing speed, executive functions, and even abstract reasoning. The fact that a majority of individuals experiences music-making as pleasant would allow long lasting involvement after retirement. Overall, the current study poses an essential starting point showing that functional neuroplasticity in older adults is possible in response to musical training.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Zatorre, R. J., Chen, J. L. & Penhune, V. B. When the brain plays music: auditory–motor interactions in music perception and production. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 8, 547–558 (2007).

Brown, R. M., Zatorre, R. J. & Penhune, V. B. Expert Music Performance: Cognitive, Neural, and Developmental Bases 57–86 (Elsevier, 2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.pbr.2014.11.021.

Harada, C. N., Natelson Love, M. C. & Triebel, K. L. Normal cognitive aging. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 29, 737–752 (2013).

Biswal, B. B. et al. Toward discovery science of human brain function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 107, 4734–4739 (2010).

Jockwitz, C. & Caspers, S. Resting-state networks in the course of aging—Differential insights from studies across the lifespan vs. amongst the old. Pflugers Arch. Eur. J. Physiol. 473, 793–803 (2021).

Raichle, M. E. The brain’s default mode network. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 38, 433–447 (2015).

Ferreira, L. K. & Busatto, G. F. Resting-state functional connectivity in normal brain aging. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 37, 384–400 (2013).

Hausman, H. K. et al. The role of resting-state network functional connectivity in cognitive aging. Front. Aging Neurosci. 12, 1–10 (2020).

Luo, C. et al. Musical training induces functional plasticity in perceptual and motor networks: Insights from resting-state fMRI. PLoS One 7, 1–10 (2012).

Fauvel, B. et al. Morphological brain plasticity induced by musical expertise is accompanied by modulation of functional connectivity at rest. Neuroimage 90, 179–188 (2014).

Klein, C., Liem, F., Hänggi, J., Elmer, S. & Jäncke, L. The ‘silent’ imprint of musical training. Hum. Brain Mapp. 37, 536–546 (2016).

Palomar-García, M. Á., Zatorre, R. J., Ventura-Campos, N., Bueichekú, E. & Ávila, C. Modulation of functional connectivity in auditory-motor networks in musicians compared with nonmusicians. Cereb. Cortex 27, 2768–2778 (2017).

Tanaka, S. & Kirino, E. The parietal opercular auditory-sensorimotor network in musicians: A resting-state fMRI study. Brain Cogn. 120, 43–47 (2018).

Leipold, S., Klein, C. & Jäncke, L. Musical expertise shapes functional and structural brain networks independent of absolute pitch ability. J. Neurosci. 41, 2496–2511 (2021).

Button, K. S. et al. Power failure: Why small sample size undermines the reliability of neuroscience. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 14, 365–376 (2013).

Amad, A. et al. Motor learning induces plasticity in the resting brain-drumming up a connection. Cereb. Cortex 27, 2010–2021 (2017).

Li, Q. et al. Musical training induces functional and structural auditory-motor network plasticity in young adults. Hum. Brain Mapp. 39, 2098–2110 (2018).

Bugos, J. A., Perlstein, W. M., McCrae, C. S., Brophy, T. S. & Bedenbaugh, P. H. Individualized piano instruction enhances executive functioning and working memory in older adults. Aging Ment. Health 11, 464–471 (2007).

Seinfeld, S., Figueroa, H., Ortiz-Gil, J. & Sanchez-Vives, M. V. Effects of music learning and piano practice on cognitive function, mood and quality of life in older adults. Front. Psychol. 4, 810 (2013).

Degé, F. & Kerkovius, K. The effects of drumming on working memory in older. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1423, 242–250 (2018).

Goh, J. O. S. Functional dedifferentiation and altered connectivity in older adults: Neural accounts of cognitive aging. Aging Dis. 2, 30–48 (2011).

Grady, C. The cognitive neuroscience of ageing. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 13, 491–505 (2012).

Mathys, C. et al. An age-related shift of resting-state functional connectivity of the subthalamic nucleus: A potential mechanism for compensating motor performance decline in older adults. Front. Aging Neurosci. 6, 1–12 (2014).

Marstaller, L., Williams, M., Rich, A., Savage, G. & Burianová, H. Aging and large-scale functional networks: White matter integrity, gray matter volume, and functional connectivity in the resting state. Neuroscience 290, 369–378 (2015).

Vieira, B. H., Rondinoni, C. & Garrido Salmon, C. E. Evidence of regional associations between age-related inter-individual differences in resting-state functional connectivity and cortical thinning revealed through a multi-level analysis. Neuroimage 211, 116662 (2020).

Sutcliffe, R., Du, K. & Ruffman, T. Music making and neuropsychological aging: A review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 113, 479–491 (2020).

Rogenmoser, L., Kernbach, J., Schlaug, G. & Gaser, C. Kee** brains young with making music. Brain Struct. Funct. 223, 297–305 (2018).

Jünemann, K. et al. Six months of piano training in healthy elderly stabilizes white matter microstructure in the fornix, compared to an active control group. Front. Aging Neurosci. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2022.817889 (2022).

Smith, S. M. et al. Correspondence of the brain’s functional architecture during activation and rest. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 13040–13045 (2009).

Biswal, B. B., Zerrin Yetkin, F., Haughton, V. M. & Hyde, J. S. Functional connectivity in the motor cortex of resting human brain using echo-planar MRI. Magn. Reson. Med. 34, 537–541 (1995).

Andrews-Hanna, J. R., Reidler, J. S., Sepulcre, J., Poulin, R. & Buckner, R. L. Functional-anatomic fractionation of the brain’s default network. Neuron 65, 550–562 (2010).

Seeley, W. W. et al. Dissociable intrinsic connectivity networks for salience processing and executive control. J. Neurosci. 27, 2349–2356 (2007).

Schneider, P. et al. Morphology of Heschl’s gyrus reflects enhanced activation in the auditory cortex of musicians. Nat. Neurosci. 5, 688–694 (2002).

Schneider, P. et al. Structural and functional asymmetry of lateral Heschl’s gyrus reflects pitch perception preference. Nat. Neurosci. 8, 1241–1247 (2005).

Gaser, C. & Schlaug, G. Brain structures differ between musicians and non-musicians. J. Neurosci. 23, 9240–9245 (2003).

Foster, N. E. V. & Zatorre, R. J. Cortical structure predicts success in performing musical transformation judgments. Neuroimage 53, 26–36 (2010).

James, C. E. et al. Musical training intensity yields opposite effects on grey matter density in cognitive versus sensorimotor networks. Brain Struct. Funct. 219, 353–366 (2014).

Bermudez, P., Lerch, J. P., Evans, A. C. & Zatorre, R. J. Neuroanatomical correlates of musicianship as revealed by cortical thickness and voxel-based morphometry. Cereb. Cortex 19, 1583–1596 (2009).

Fernández-Miranda, J. C. et al. Asymmetry, connectivity, and segmentation of the arcuate fascicle in the human brain. Brain Struct. Funct. 220, 1665–1680 (2015).

Koelsch, S. Toward a neural basis of music perception—A review and updated model. Front. Psychol. 2, 1–20 (2011).

Oechslin, M. S., Van De Ville, D., Lazeyras, F., Hauert, C. A. & James, C. E. Degree of musical expertise modulates higher order brain functioning. Cereb. Cortex 23, 2213–2224 (2013).

Berkowitz, A. L. & Ansari, D. Generation of novel motor sequences: The neural correlates of musical improvisation. Neuroimage 41, 535–543 (2008).

Rottschy, C. et al. Modelling neural correlates of working memory: A coordinate-based meta-analysis. Neuroimage 60, 830–846 (2012).

Eickhoff, S. B. et al. Coordinate-based activation likelihood estimation meta-analysis of neuroimaging data: A random-effects approach based on empirical estimates of spatial uncertainty. Hum. Brain Mapp. 30, 2907–2926 (2009).

Worschech, F. et al. Fine motor control improves in older adults after 1 year of piano lessons: Analysis of individual development and its coupling with cognition and brain structure. Eur. J. Neurosci. 57, 2040–2061. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejn.16031 (2023).

Seidler, R. D. et al. Motor control and aging: Links to age-related brain structural, functional, and biochemical effects. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 34, 721–733 (2010).

Hoogendam, Y. Y. et al. Older age relates to worsening of fine motor skills: A population based study of middle-aged and elderly persons. Front. Aging Neurosci. 6, 1–7 (2014).

Fotuhi, M., Do, D. & Jack, C. Modifiable factors that alter the size of the hippocampus with ageing. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 8, 189–202 (2012).

Koelsch, S. Brain correlates of music-evoked emotions. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 15, 170–180 (2014).

Teki, S. et al. Navigating the auditory scene: An expert role for the hippocampus. J. Neurosci. 32, 12251–12257 (2012).

Watanabe, T., Yagishita, S. & Kikyo, H. Memory of music: Roles of right hippocampus and left inferior frontal gyrus. Neuroimage 39, 483–491 (2008).

James, C. E., Britz, J., Vuilleumier, P., Hauert, C. A. & Michel, C. M. Early neuronal responses in right limbic structures mediate harmony incongruity processing in musical experts. Neuroimage 42, 1597–1608 (2008).

Oldfield, R. C. The assessment and analysis of handedness: The Edinburgh inventory. Neuropsychologia 9, 97–113 (1971).

Müllensiefen, D., Gingras, B., Musil, J. & Stewart, L. The musicality of non-musicians: An index for assessing musical sophistication in the general population. PLoS One 9, e89642 (2014).

Ihle, A., Gouveia, É. R., Gouveia, B. R. & Kliegel, M. The cognitive telephone screening instrument (COGTEL): A brief, reliable, and valid tool for capturing interindividual differences in cognitive functioning in epidemiological and aging studies. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Dis. Extra 7, 339–345 (2017).

Kliegel, M., Martin, M. & Jäger, T. Development and validation of the cognitive telephone screening instrument (COGTEL) for the assessment of cognitive function across adulthood. J. Psychol. 141, 147–170 (2007).

James, C. E. et al. Train the brain with music (TBM): brain plasticity and cognitive benefits induced by musical training in elderly people in Germany and Switzerland, a study protocol for an RCT comparing musical instrumental practice to sensitization to music. BMC Geriatr. 20, 418 (2020).

Worschech, F. et al. Improved speech in noise perception in the elderly after 6 months of musical instruction. Front. Neurosci. 15, 696240 (2021).

Marques, J. P. et al. NeuroImage MP2RAGE, a self bias- fi eld corrected sequence for improved segmentation and T 1 -map** at high field. Neuroimage 49, 1271–1281 (2010).

Yan, C.-G., Wang, X.-D., Zuo, X.-N. & Zang, Y.-F. DPABI: Data processing & analysis for (resting-state) brain imaging. Neuroinformatics 14, 339–351 (2016).

Ashburner, J. A fast diffeomorphic image registration algorithm. Neuroimage 38, 95–113 (2007).

Friston, K. J., Williams, S., Howard, R., Frackowiak, R. S. J. & Turner, R. Movement-related effects in fMRI time-series. Magn. Reson. Med. 35, 346–355 (1996).

Jenkinson, M., Bannister, P., Brady, M. & Smith, S. Improved optimization for the robust and accurate linear registration and motion correction of brain images. Neuroimage 17, 825–841 (2002).

Rolls, E. T., Huang, C. C., Lin, C. P., Feng, J. & Joliot, M. Automated anatomical labelling atlas 3. Neuroimage 206, 116189 (2020).

Fitzhugh, M. C., Hemesath, A., Schaefer, S. Y., Baxter, L. C. & Rogalsky, C. Functional connectivity of Heschl’s Gyrus associated with age-related hearing loss: a resting-state fMRI study. Front. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02485 (2019).

Jabusch, H. C., Vauth, H. & Altenmüller, E. Quantification of focal dystonia in pianists using scale analysis. Mov. Disord. 19, 171–180 (2004).

Jabusch, H. C., Alpers, H., Kopiez, R., Vauth, H. & Altenmüller, E. The influence of practice on the development of motor skills in pianists: A longitudinal study in a selected motor task. Hum. Mov. Sci. 28, 74–84 (2009).

Tiffin, J. & Asher, E. J. The Purdue Pegboard: Norms and studies of reliability and validity. J. Appl. Psychol. 32, 234–247 (1948).

Hoffstaedter, F. et al. The role of anterior midcingulate cortex in cognitive motor control: Evidence from functional connectivity analyses. Hum. Brain Mapp. 35, 2741–2753 (2014).

Clark, D. L., Boutros, N. N. & Mendez, M. F. Limbic system: Cingulate cortex. In The Brain and Behavior (eds Clark, D. L. et al.) 197–215 (Cambridge University Press, 2018). https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108164320.013.

Palomero-Gallagher, N., Vogt, B. A., Schleicher, A., Mayberg, H. S. & Zilles, K. Receptor architecture of human cingulate cortex: Evaluation of the four-region neurobiological model. Hum. Brain Mapp. 30, 2336–2355 (2009).

Leech, R. & Sharp, D. J. The role of the posterior cingulate cortex in cognition and disease. Brain 137, 12–32 (2014).

Vogt, B. A. Pain and emotion interactions in subregions of the cingulate gyrus. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 6, 533–544 (2005).

Mayka, M. A., Corcos, D. M., Leurgans, S. E. & Vaillancourt, D. E. Three-dimensional locations and boundaries of motor and premotor cortices as defined by functional brain imaging: A meta-analysis. Neuroimage 31, 1453–1474 (2006).

**a, M., Wang, J. & He, Y. BrainNet viewer: A network visualization tool for human brain connectomics. PLoS One 8, e68910 (2013).

Wan, C. Y. & Schlaug, G. Music making as a tool for promoting brain plasticity across the life span. Neuroscientist 16, 566–577 (2010).

Chen, J. L., Rae, C. & Watkins, K. E. Learning to play a melody: An fMRI study examining the formation of auditory-motor associations. Neuroimage 59, 1200–1208 (2012).

Amiez, C., Hadj-Bouziane, F. & Petrides, M. Response selection versus feedback analysis in conditional visuo-motor learning. Neuroimage 59, 3723–3735 (2012).

Hardwick, R. M., Rottschy, C., Miall, R. C. & Eickhoff, S. B. A quantitative meta-analysis and review of motor learning in the human brain. Neuroimage 67, 283–297 (2013).

Giovannelli, F. et al. Role of the dorsal premotor cortex in rhythmic auditory-motor entrainment: A perturbational approach by rTMS. Cereb. Cortex 24, 1009–1016 (2014).

Hickok, G. & Poeppel, D. Dorsal and ventral streams: A framework for understanding aspects of the functional anatomy of language. Cognition 92, 1–12 (2004).

Rauschecker, J. P. An expanded role for the dorsal auditory pathway in sensorimotor control and integration. Hear. Res. 271, 16–25 (2011).

Halwani, G. F., Loui, P., Rüber, T. & Schlaug, G. Effects of practice and experience on the arcuate fasciculus: Comparing singers, instrumentalists, and non-musicians. Front. Psychol. 2, 156 (2011).

Vaquero, L., Ramos-Escobar, N., François, C., Penhune, V. & Rodríguez-Fornells, A. White-matter structural connectivity predicts short-term melody and rhythm learning in non-musicians. Neuroimage 181, 252–262 (2018).

Moore, E., Schaefer, R. S., Bastin, M. E., Roberts, N. & Overy, K. Diffusion tensor MRI tractography reveals increased fractional anisotropy (FA) in arcuate fasciculus following music-cued motor training. Brain Cogn. 116, 40–46 (2017).

Nan, Y. & Friederici, A. D. Differential roles of right temporal cortex and Broca’s area in pitch processing: Evidence from music and mandarin. Hum. Brain Mapp. 34, 2045–2054 (2013).

Chen, X. et al. The lateralized arcuate fasciculus in developmental pitch disorders among mandarin amusics: Left for speech and right for music. Brain Struct. Funct. 223, 2013–2024 (2018).

Saari, P., Burunat, I., Brattico, E. & Toiviainen, P. Decoding musical training from dynamic processing of musical features in the brain. Sci. Rep. 8, 1–12 (2018).

Beckmann, C. F., DeLuca, M., Devlin, J. T. & Smith, S. M. Investigations into resting-state connectivity using independent component analysis. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 360, 1001–1013 (2005).

Kolb, B. & Whishaw, I. Q. Fundamentals of Human Neuropsychology (Macmillan, 2009).

Cona, G. & Semenza, C. Supplementary motor area as key structure for domain-general sequence processing: A unified account. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 72, 28–42 (2017).

Sheets, J. R. et al. Parcellation-based modeling of the supplementary motor area. J. Neurol. Sci. 421, 117322 (2021).

Hyde, K. L. et al. Musical training shapes structural brain development. J. Neurosci. 29, 3019–3025 (2009).

Uddin, L. Q., Clare Kelly, A. M., Biswal, B. B., Xavier Castellanos, F. & Milham, M. P. Functional connectivity of default mode network components: Correlation, anticorrelation, and causality. Hum. Brain Mapp. 30, 625–637 (2009).

Fox, M. D. et al. The human brain is intrinsically organized into dynamic, anticorrelated functional networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 102, 9673–9678 (2005).

Kelly, A. M. C., Uddin, L. Q., Biswal, B. B., Castellanos, F. X. & Milham, M. P. Competition between functional brain networks mediates behavioral variability. Neuroimage 39, 527–537 (2008).

Leech, R., Braga, R. & Sharp, D. J. Echoes of the brain within the posterior cingulate cortex. J. Neurosci. 32, 215–222 (2012).

Rushworth, M. F., Johansen-Berg, H., Göbel, S. & Devlin, J. The left parietal and premotor cortices: Motor attention and selection. Neuroimage 20, S89–S100 (2003).

Albouy, G. et al. Both the hippocampus and striatum are involved in consolidation of motor sequence memory. Neuron 58, 261–272 (2008).

Cole, D. M., Smith, S. M. & Beckmann, C. F. Advances and pitfalls in the analysis and interpretation of resting-state FMRI data. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 4, 1–15 (2010).

Oschwald, J. et al. Brain structure and cognitive ability in healthy aging: A review on longitudinal correlated change. Rev. Neurosci. 31, 1–57 (2019).

Turney, I. C. et al. APOE ε4 and resting-state functional connectivity in racially/ethnically diverse older adults. Alzheimer’s Dement. Diagn. Assess. Dis. Monit. 12, 1–8 (2020).

Misiura, M. B. et al. Race modifies default mode connectivity in Alzheimer’s disease. Transl. Neurodegener. 9, 8 (2020).

Shiekh, S. I. et al. Ethnic differences in dementia risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 80, 337–355 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation, grant no. 323965454) and the Swiss National Science Foundation (grant no. 100019E-170410). The Dr. Med. Kurt Fries Foundation, the Dalle Molle Foundation, and the Edith Maryon Foundation also provided financial support. We would like to thank Laura Abdili, Samantha Stanton, Fynn Lautenschläger, and Charlotte Weinberg for their help with data acquisition. Further, we would like to thank the technical staff of the imaging platform at the Brain and Behaviour Laboratory (BBL, http://bbl.unige.ch/) for its continuous support. At last, we are very grateful to Yamaha for kindly providing us with the electronic pianos, headphones, and stands, while fully respecting the research independence of the team.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.J. Conceptualization, Investigation, Data Curation, Formal Analysis, Writing—Original Draft Preparation, Writing—Review, and Editing. A.E. Formal Analysis, Writing—Review, and Editing. D.M. and F.W. Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing—Review and Editing. D.S.S., F.G. and D.V.D.V. Conceptualization, Writing—Review and Editing. M.K. Detailed Input on Funding Acquisition, Conceptualization, Writing—Review and Editing. E.A. Funding Acquisition, Conceptualization, Writing—Review and Editing. T.H.C.K. Detailed Input on Funding Acquisition, Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing—Review and Editing. C.E.J. Funding Acquisition, Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing—Review and Editing. C.S. Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing—Review and Editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jünemann, K., Engels, A., Marie, D. et al. Increased functional connectivity in the right dorsal auditory stream after a full year of piano training in healthy older adults. Sci Rep 13, 19993 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-46513-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-46513-1

- Springer Nature Limited