Abstract

Renal tubular atrophy is a hallmark of chronic kidney disease. The cause of tubular atrophy, however, remains elusive. Here we report that reduction of renal tubular cell polynucleotide phosphorylase (PNPT1) causes renal tubular translation arrest and atrophy. Analysis of tubular atrophic tissues from renal dysfunction patients and male mice with ischemia-reperfusion injuries (IRI) or unilateral ureteral obstruction (UUO) treatment shows that renal tubular PNPT1 is markedly downregulated under atrophic conditions. PNPT1 reduction leads to leakage of mitochondrial double-stranded RNA (mt-dsRNA) into the cytoplasm where it activates protein kinase R (PKR), followed by phosphorylation of eukaryotic initiation factor 2α (eIF2α) and protein translational termination. Increasing renal PNPT1 expression or inhibiting PKR activity largely rescues IRI- or UUO-induced mouse renal tubular injury. Moreover, tubular-specific PNPT1-knockout mice display Fanconi syndrome-like phenotypes with impaired reabsorption and significant renal tubular injury. Our results reveal that PNPT1 protects renal tubules by blocking the mt-dsRNA-PKR-eIF2α axis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD), defined by persistent albuminuria and/or decline in glomerular filtration rate (GFR), is a serious disease that affects 1 in every 7-10 adults worldwide1. Although the research about CKD has long been focused on glomerulus, accumulating evidences has demonstrated that renal tubular injury and atrophy is also a hallmark of CKD2,3,4,5. In fact, the extent of renal dysfunction of CKD patients correlates more closely with tubular injuries, including tubular atrophy and interstitial fibrosis, than with changes in glomerular morphology6. Given the significance of tubular atrophy in CKD progression and as a predictor of GFR decline superior to glomerular nephropathy7, various investigators have studied the causes of renal tubular atrophy, including tubular epithelial cell apoptosis, cell senescence, peritubular capillary rarefaction and downstream tubule ischemia, oxidative stress, epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and interstitial inflammation8; however, the mechanisms leading to renal tubular atrophy in CKD are still poorly understood.

Renal tubular cells, accounting for approximately 90% of the cortex, are highly enriched in mitochondria9. The primary function of the proximal tubules is reabsorption, and such active process requires a large amount of energy produced by mitochondria10. It has been widely reported that mitochondrial dysfunction, including mitochondrial biogenesis, dynamics, and oxidative stress, is tightly linked to renal tubular cell disease11,12. He et al. identified that a decreased supply of fuel and increased demand for oxygen by mitochondria in renal tubules are pivotal pathological mechanisms of diabetic tubulopathy in diabetic kidney disease (DKD)11. Renal tubular dysfunctional mitochondria may accelerate the initiation of early-stage kidney diseases such as diabetic tubulopathy12. Mitochondrial dysfunction is also inseparable from increased reactive oxygen species production and energy expenditure by tubular cells, while the glycolytic pathway may serve as a self-protection mechanism in DKD13. To meet aerobic metabolism and high energy requirements, mitochondria-rich renal proximal tubule cells must maintain mitochondrial homeostasis and dynamic turnover, which makes renal proximal tubule cells very vulnerable to mitochondrial impairment9. The homeostasis and dynamic turnover of mitochondrial double-stranded RNAs (mt-dsRNAs) are also critical to cell fate. To most mammalian cells, cytosolic dsRNAs remain an essential threat14. Increased oxidative stress in tubular cells under CKD conditions not only increases the generation of mt-dsRNAs, but also results in their leakage from the mitochondria into the cytoplasm. Recently, numerous studies reported the involvement of mt-dsRNAs efflux into cytoplasm to activate the innate immune system in various human diseases, including alcohol-induced liver damage15, Huntington’s disease16, and osteoarthritis17. In the cytoplasm, various RNA sensor proteins can recognize these mt-dsRNAs18,19,20. One such sensor protein is dsRNA-activating protein kinase R (PKR), which can further activate eukaryotic initiation factor 2α (eIF2α) at Ser51, leading to termination of general protein synthesis18,21,22. However, the cellular relocation of mt-dsRNAs in renal tubular cells under various disease condition and their potential function in renal atrophy have not been examined.

To explore the potential role of mt-dsRNAs in promoting renal tubular injury, we undertook an unbiased approach by examining kidney tissues from patients with different renal dysfunctions, as well as from mice with ischemia reperfusion-induced injury (IRI) or unilateral ureteral obstruction (UUO) procedures. These tissues all displayed renal tubular injury in various degrees compared to their respective controls. We found that, in injured renal tubular cells, mt-dsRNAs were widely spread in the cytoplasm where they activated the PKR-eIF2α signaling axis, resulting in termination of general protein synthesis, cell injury and apoptosis. This study further identified the reduction of renal tubular PNPT1 induced by TGFβ1, hyperglycemia or LPS as the mechanism underlying the relocation of mt-dsRNAs from mitochondria into the cytoplasm. Supporting the role of PNPT1 in controlling renal tubular cell mt-dsRNA homeostasis and injury, renal tubular-specific PNPT1-deficient mice exhibited severe impaired reabsorption and significant renal tubular injuries. The present study reveals an important role of PNPT1 in protecting renal tubules via inhibiting the mt-dsRNA-PKR-eIF2α signaling axis.

Results

Detection of cytosolic dsRNAs in atrophic renal tubular cells but not podocytes

Given that cytosolic dsRNAs are an essential threat for all mammalian cells14, we examined the level and location of dsRNAs in the cytoplasm of various renal cells under normal or disease conditions using J2 antibody, which specifically stains dsRNAs. Kidney tissue sections from patients with ongoing acute tubular necrosis (ATN) who displayed severe renal tubular injury were analyzed. As shown in Fig. 1a, a significant amount of J2-labeled dsRNAs was detected in renal tubular cells from ATN patients but not in non-injured renal tubular cells derived from the paracancerous kidney tissues. Interestingly, no dsRNA was detected in podocytes from ATN patients and non-renal tubular injury donors, suggesting a potentially specific linkage between cytosolic dsRNAs and renal tubular injuries. Quantitative analysis of cytosolic dsRNAs showed a strong increase of cytosolic dsRNA level in injured renal tubules from ATN patients (n = 12) compared to renal tubules from non-renal tubular injury donors (n = 5) (Fig. 1b). To confirm the high level of cytosolic dsRNAs in renal tubular cells as the common cause for renal tubular injury in various kidney diseases, we examined kidney tissue sections from patients with various renal dysfunctions, including diabetic nephropathy (DN, n = 14), lupus nephritis (LN, n = 15), IgA nephropathy (IgAN, n = 16), membranous nephropathy (MN, n = 13) or focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS, n = 15). Various degrees of renal tubular injury in all these tissues were confirmed pathologically. As shown in Fig. 1c, aquaporin 1 (AQP1)-expressing renal tubules (green) from various kidney diseases all exhibited significant damage compared to control renal tubules. Correlatively, a large amount of J2-stained dsRNA (red) was detected in the cytoplasm of injured tubular cells. Quantitative analysis further showed that cytoplasmic dsRNA levels in renal tubular cells were positively correlated to the degree of tubular injury (Fig. 1d).

a Immunostaining of cytosolic dsRNA by J2 antibody in tubule and glomerulus from acute tubular necrosis (ATN) patients and controls. Tissue sections were stained with anti-aquaporin 1 (AQP1) antibody (tubular cell) or anti-synaptopodin antibody (podocyte). b Quantification of cytosolic dsRNA levels in tubules and glomerulus (5 patients/group). c Immunostaining of dsRNA (J2) from 85 patients with various degrees of renal tubular injury, including ATN (5 males and 7 females), diabetic nephropathy (DN, 8 males and 6 females), IgA nephropathy (IgAN, 9 males and 7 females), lupus nephritis (LN, 5 males and 10 females), membranous nephropathy (MN, 8 males and 5 females) and focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS, 6 males and 9 females), as well as 5 non-renal tubular injury controls (3 males and 2 females). d Evaluation of tubular injury degree and cytosolic dsRNA levels. e Cytosolic dsRNA staining by J2 antibody in renal tubule from ischemia reperfusion-induced injury (IRI) or unilateral ureteral obstruction (UUO) mouse models. f Evaluation of renal tubular injury degree and cytosolic dsRNA levels in IRI or UUO mouse models. g Cytosolic mt-dsRNA levels in renal tubules of IRI and Sham mouse groups. h Renal tubular cytosolic levels of mt-dsRNAs detected using specific probes against the heavy and light strand (5 mice/group). Scale bars, 50 μm. The above experiments were successfully repeated three times. Two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test was performed in b, and the results were presented as mean ± SEM. In box plots (g, f), the centre line shows the median, lower and upper hinges of boxes represent 25th to 75th percentiles, and whiskers extend to minimum and maximum values. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

IRI and UUO procedures are two experimental models widely used to study renal tubular injury and fibrosis23,24,7a). To our surprise, these PNPT1-knockout mice developed a significantly smaller body compared to their WT littermates (Fig. 7b, c). Kidney tissue examination by H&E staining also showed that PNPT1-knockout mice had markedly higher renal injury scores than did WT mice (Fig. 7d). These results suggest that lower body weight in PNPT1-knockout mice is due to renal tubular dysfunction. Supporting this notion, we found that PNPT1-knockout mice exhibited a Fanconi syndrome-like phenotype in terms of impaired reabsorption. Bone mineral density scanning showed that PNPT1-knockout mice had a severe bone structure deformation similar to that in rickets with a markedly lower bone mineral density compared to WT mice (Fig. 7e). In line with this, significant loss of serum calcium, as well as serum phosphorus at late stage, was found in PNPT1-knockout mice (Fig. 7f).

a Top: genotype identification and PNPT1 levels in WT and renal tubular-specific PNPT1-KO (KO) mice. Bottom: immunofluorescence labeling and WB analysis of PNPT1 in WT and KO renal tubules. b Image of WT and KO mice. c Weight monitoring of WT and KO mice (7 mice /group). d Tubular injury score in WT and KO mice (5 mice/group, 8w). Arrows: injured tubules. e Left: Bone mineral density scanning of WT and KO mice. Right: quantification of bone mineral density (10 mice/group, 8w). f Levels of serum calcium and phosphorus (5 mice/group, 6-10w). g Urine level of glucose, uric acid, phosphorus and potassium in WT and KO mice (6 mice/group, 8w). h Kidney/body weight index (6 mice/group, 8w). i Serum creatinine (Scr, left) and levels of renal tubular injury markers (right) in WT and KO mice (5 mice/group, 8w). j Left: TEM image of mitochondrial damage in renal tubule from WT and KO mice. Right: quantification of renal tubular mitochondrial damage (5 mice/group, 8w). Arrows: injured mitochondria. k Left: Masson staining in kidney tissue sections from WT and KO mice. Right: quantification of renal fibrosis (5 mice/group, 8w). Arrows: fibrotic tubules. l Left: TUNEL assay of kidney tissue sections from WT and KO mice. Right: quantification of renal tubular apoptosis (5 mice/group, 8w). Arrows: apoptotic tubules. Scale bars in a, d, k, and l, 50 μm. Scale bar in j, 2 μm. The above experiments were successfully repeated three times. Two-tailed unpaired t test was performed for the statistical analyses in (d, e, g, h, j–l), Two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test was performed in f, i, and the results were presented as the mean ± SEM. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Renal tubular dysfunction in PNPT1-knockout mice was further analyzed. At age of 8 weeks, PNPT1-knockout mice showed higher levels of glucose, uric acid, phosphorus and potassium in urine compared to WT mice (Fig. 7g). A lower kidney/body weight ratio (Fig. 7h) but higher Scr (Fig. 7i, left) and urinary levels of renal tubular injury markers (Fig. 7i, right) were detected in PNPT1-knockout mice. Given that PNPT1 deficiency likely disrupts mt-dsRNA homeostasis and mitochondrial function, we examined the mitochondrial structure in renal tubular cells from PNPT1-knockout and WT mice using transmission electronic microscope (TEM). As shown in Fig. 7j, PNPT1-knockout mice displayed more significant matrix destruction, cristae fragmentation, cavity enlargement and mitochondrial swelling compared to WT mice. Masson staining of kidney tissue sections from WT and PNPT1-knockout mice also showed a significantly higher degree of renal fibrosis in PNPT1-knockout mice than in WT mice (Fig. 7k). As renal tubular injury eventually leads to cell apoptosis, we assessed the level of cell apoptosis in the mouse kidney. As shown by the TUNEL assay, PNPT1-knockout mice exhibited significantly higher apoptosis levels in renal tubular cells than in WT mice (Fig. 7l).

Discussion

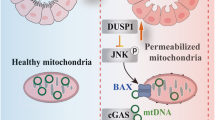

This study reveals that reduction of renal tubular PNPT1 under various renal dysfunctions, including ATN, DN, LN, IgAN, FSGS, etc., is a key causative factor of renal tubular injury. As depicted in Fig. 4f, stimulated by HG, TGFβ or LPS, all three factors of which are tightly related to renal tubular cell injury38,39, renal tubular cell PNPT1 is drastically reduced. The PNPT1 reduction will lose control of mitochondrial RNA homeostasis, resulting in leakage of mt-dsRNAs into the cytoplasm where they activate PKR and initiate the PKR-eIF2α signaling axis to terminate general protein translation. Suppression of protein synthesis in renal tubular cells then leads to cell injury and eventually apoptosis.

Given its primary function of reabsorption which requires a great amount of energy produced by mitochondria, renal tubular cells indeed consist of a much higher number of mitochondria than other renal cells, such as podocytes10. No surprising, renal tubular cells, particularly proximal tubule cells (PTCs), are very vulnerable to mitochondrial impairment. It has been widely reported that various mitochondrial dysfunctions are tightly linked to various renal tubular cell diseases11,12. However, most studies that investigated the role of mitochondria in maintaining renal tubular cell function have been focused on metabolic reprograming, as well as oxidative stress factors such as reactive oxygen species (ROS)48. Our studies here demonstrate that the homeostasis and dynamic turnover of mt-dsRNAs are also key factors for the fate of renal tubular cells. As an essential threat to most mammalian cells, dsRNAs can be recognized by various RNA sensors, including RIG-I/MDA5, which triggers a type I interferon response31, and PKR, which initiates an integrated stress response (ISR) that terminates general protein synthesis. As cytosolic mt-dsRNAs induced by silencing renal tubular cell PNPT1 rapidly suppressed general protein synthesis (Fig. 4a), our results indicate that PKR-eIF2α-mediated ISR plays a major role in mt-dsRNA-induced renal tubular injures. In fact, as a conservative anti-viral host defense mechanism, the ISR induced by viral dsRNAs has been extensively characterized49. However, recent studies demonstrate that ISR also modulates mammalian cell proliferation and survival because it can be initiated by endogenous dsRNAs, particularly mt-dsRNAs18. In mammals, mitochondrial DNA can generate large amounts of overlap** transcripts, which are capable of forming long dsRNAs. By detecting cytosolic mt-dsRNAs or nuclear dsRNAs, Kim et al. showed that PKR served as a sensor for mitochondrial and nuclear signaling cues in regulating cellular metabolism18. Our results demonstrate that cytosolic mt-dsRNAs in injured renal tubular cells indeed bind to and activate PKR, which in turn, phosphorylates eIF2α, leading to the termination of protein translation.

Supporting the role of ISR induced by mt-dsRNA-PKR-eIF2α axis in renal tubular injury, our intervention studies using both IRI and UUO mouse renal tubular injury models show that compensating the PNPT1 reduction in mouse renal tubules can markedly decrease cytosolic mt-dsRNA levels (Fig. 5b, f) and prevent renal tubular injures, as evidenced by reduced Scr, urinary KIM-1 levels (Fig. 5c, g) and injury index (Fig. 5d, h). Moreover, directly inhibiting renal tubular cell PKR activity by C16 also strongly protects mice against renal tubular injures induced by IRI and UUO procedures (Fig. 6). The protective role of PKR inhibition is in agreement with a previous report that PKR deficiency decreases congestive heart failure induced by systolic overload50.

As an evolutionarily conservative 3′ -to-5′ exoribonuclease that is involved in RNA processing and degradation, mitochondria-associated PNPT1 controls the homeostasis of mitochondria RNAs51. Supporting this, reduction of PNPT1 in renal tubular cells, results in elevation of cytosolic mt-dsRNAs (Fig. 3d). The defect of PNPT1 has been shown to result in mitochondrial dysfunction and various neurologic problems such as autosomal recessive deafness52,53. Although no such PNPT1 deficiency or mutation has been linked to renal diseases, our results clearly show that PNPT1 activity is required to maintain the normal function of renal tubular cells. A significant reduction of renal tubular PNPT1 is found in different renal diseases which are associated with various degrees of renal injury (Fig. 2). Although the underlying molecular basis remains unknown, mechanistical studies indicate that PNPT1 reduction in renal tubular cells can be achieved by renal tubular cell injury factors TGFβ1, hyperglycemia and LPS (Fig. 3a). Finally, the essential role of PNPT1 in maintaining normal renal tubular function under various stress conditions is validated in renal tubular-specific PNPT1-knockout mice. Compared to WT mice, PNPT1-knockout mice displayed significant renal tubular injury (Fig. 7d), accompanied with higher levels of Scr and renal tubular injury markers (Fig. 7i). As calcium filtered by the kidney is efficiently (>98%) reabsorbed by renal tubules to maintain the serum concentration54, damage of renal tubular cells, particularly PTCs, would result in impairment of calcium reabsorption and significant bone loss. Indeed, we found that PNPT1-knockout mice displayed severe impaired reabsorption, as evidenced by a lower body weight (Fig. 7c), a severe bone structure deformation, a markedly lower bone mineral density (Fig. 7e) and significant loss of serum calcium and phosphorus (Fig. 7f). Direct analysis of renal tubular cell mitochondria at ultrastructural level confirms that PNPT1 deficiency markedly disrupts mt-dsRNA homeostasis and mitochondria function, causing significant matrix destruction, cristae fragmentation, cavity enlargement and mitochondrial swelling (Fig. 7j).

In conclusion, these findings reveal that reduction of renal tubular PNPT1 under various injury conditions is a major cause of renal tubular injury, and provide PNPT1 as a therapeutic target for protecting against renal tubule injury.

Methods

Statement

All protocols concerning the use of patient samples in this study were approved by the Human Subjects Committee of **ling Hospital, Nan**g University School of Medicine (2019NZKYKS-008-01). A written informed consent was obtained from each patient whose sample is used in the study. Animal study was approved by Animal Ethical and Welfare Committee of Nan**g University (IACUC-2112001). Mice were housed, bred and studied in accordance with approved protocols. Mouse euthanasia was done first by anaesthesia and then followed by cervical dislocation.

Cells, antibodies, and reagents

HK2 cells were obtained from American Tissue and Cell Center (ATCC, CRL-2190) and grown as a monolayer in DMEM/F12 (Gibco) supplemented with 10% FBS (Gibco), 100 U/ml penicillin (Gibco), 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Gibco) and ITS (Sigma-Aldrich). Primary antibodies for dsRNA mAb J2 (Scions, 10010500, 1:200), PNPT1 (Abcam, ab96176, 1:200/2000), AQP1 (Abcam, 168387, 1:200), synaptopodin (Abcam, ab224491, 1:100), podocin (Sigma-Aldrich, P0372, 1:100), PKR (Abcam, ab32506, 1:1000), p-PKR (Abcam, ab32036, 1:1000), eIF2α (CST, 5324 S, 1:1000), p-eIF2α (CST, 3398 S, 1:1000), ATF4 (Abcam, ab184909), COX IV (Abcam, ab14744, 1:1000), LaminB1 (Abcam, ab65986, 1:1000), and α-tubulin (Proteintech, 11224-1-AP, 1:2000) were used for immunofluorescence and western blot analysis; Secondary antibodies including goat anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 488 (Invitrogen, A11001, 1:1000), donkey anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 594 (Invitrogen, A21207, 1:1000), donkey anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488 (Invitrogen, A21206, 1:1000), goat anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 594 (Invitrogen, A11005, 1:1000), goat anti-mouse IgG-HRP (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-2005, 1:1000) and goat anti-rabbit IgG-HRP (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-2004, 1:1000) were used correspondingly. DAPI was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (sc-3598, 1:1000). TGFβ (R&D Systems, 7754), LPS (Sigma-Aldrich, L2630), HG (Sigma-Aldrich, G7021) were used. Digitonin (Sigma-Aldrich, D141) were used for membrane permeabilization. KIM-1 (Abcam, ab213477), NGAL (Abcam, ab118901), β2-MG (Abcam, ab223590) ELISA quantitation kits, creatinine kit (Sigma-Aldrich, MAK080), calcium assay kit (Sigma-Aldrich, MAK022) and phosphorus microplate assay kit (Absin, 580107) were purchased for renal tubular injury assessment. Lipofectamine RNAi MAX (Invitrogen, 13778150) were used for transfection. PKR inhibitor (C16) was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (I9785) and dissolved in DMSO prior to experiment. IMT1 was obtained from MCE (HY-134539) and dissolved in DMSO prior to experiment. FITC-Annexin V Apoptosis Detection Kit (Invitrogen, V13241) and TUNEL Bright-Green apoptosis detection kit (Vazyme, A112) were used for apoptosis analysis. Collagenase D (1 mg/mL, C6885), protease (1 mg/mL, P6911) and DNaseI (1 U/mL, D5025) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Click-iT® Plus OPP Protein Synthesis Assay Kits were purchased from Life Technologies (C10456). PierceTM Classic IP Kit were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (26146). RiboTM Fluorescent In Situ Hybridization Kit were purchased from Ribo (C10910). PNPT1 AAV were purchased from OBiO (H131559). siPNPT1 plasmid (siG000087178A-1-5) and siPKR plasmid (siB161220105622-1-5) were purchased from Ribo.

Kidney biopsy

Kidney tissues were obtained through percutaneous renal biopsy from patients with ATN (n = 12, 5 males and 7 females), DN (n = 14, 8 males and 6 females), IgAN (n = 16, 9 males and 7 females), LN (n = 15, 5 males and 10 females), MN (n = 13, 8 males and 5 females) and FSGS (n = 15, 6 males and 9 females), as well as 5 non-renal tubular injury controls (3 males and 2 females). Non-tubular injury paracancerous renal tissues (n = 5) were obtained from renal clear cell cancer patients. All patients were diagnosed based on renal biopsies at the National Clinical Research Center of Kidney Diseases, **ling Hospital, Nan**g University School of Medicine.

Mouse strains and experimental renal tubular injury models

Male C57BL/6 J (8 weeks, 22–25 g) and renal tubular cell-specific PNPT1-knockout (KO) mice (1-18 weeks, male) were obtained from the Model Animal Research Center of Nan**g University. In brief, PNPT1-flox homozygous were first generated using the CRISPR/Cas9 system, and PNPT1-KO mice were obtained by mating PNPT1-flox homozygous and Ggt-Cre mice. All mice were backcrossed to a C57BL/6 J background. All mice were fed with lab diet (SWC9101) under standard conditions of constant temperature (22 ± 1 °C), humidity (relative, 30%), in a pathogen-free facility and exposed to a 12-h light/dark cycle. Inductions of kidney IRI and UUO were performed as described previously55. Briefly, after mice were anesthetized, a midline abdominal incision was made and bilateral renal pedicles were clipped for 35 min using microaneurysm clamps. After removal of the clamps, reperfusion of the kidneys was visually confirmed. The incision was then closed and the animal was allowed to recover. During the ischemic period, body temperature was maintained between 37 °C using a temperature-controlled heating system. Blood urine and tissue samples were obtained at 1d and 3d post-IRI. In the UUO model, the left ureter was ligated at two points and cut between them. Mice were sacrificed 7d and 14d after the procedure. To overexpress PNPT1 in mouse renal tubule, PNPT1-expressing AAV (PNPT1 AAV) and control AAV (Ctrl AAV) were generated (OBIO Technology). 1 × 1013 VG/ml PNPT1 AAV or Ctrl AAV were in situ injected into mouse kidney (20 μl per mouse) during IRI model establishment. To block PKR activity, PKR inhibitor (C16, 500 μg/ml) was injected intraperitoneally three days in a row following IRI or UUO procedure. For monitoring mouse renal tubular injury, urine samples were collected over 24 h once a week. Renal tubular injury markers including urinary creatinine, KIM-1, NGAL and β2-MG were measured. To suppress mtRNA expression, IMT1 (30 mg/kg) was injected intraperitoneally three days in a row after IRI or UUO procedure. The kidney tissues were collected for H&E staining and TUNEL analysis. To determine tubular injury, defined as loss of the brush border, compensatory tubular dilatation and detachment, tubular apoptosis and cellular casts, a semiquantitative scoring method was used. Score 0 represents injury area less than 10%, whereas 1, 2, 3 and 4 represent the injury involving 10–25, 25–50, 50–75 and >75% of the renal tubular area, respectively. At least 12 randomly chosen fields under the microscope were evaluated for each mouse tissue section and an average score was calculated. To monitor renal tubular reabsorption, bone mineral density (BMD) was evaluated by Ultra Focus DXA (Faxitron), while urinary calcium and urinary phosphorus were detected with the calcium assay and phosphorus microplate assay kits, respectively.

Cell treatment

For mimicking renal tubular cell injury in AKI and CKD conditions, HK2 cells were incubated with 10 ng/mL TGFβ, 75 μg/mL LPS or 40 mM HG for various indicated times. For cell transfection, HK2 cells were seeded in a 6-well plate and cultured to a confluence of 70–80%. Cells were then transfected with PNPT1 siRNAs (final concentration of 20 nM) or control oligonucleotide with Lipofectamine RNAi MAX according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For blocking PKR-eIF2α pathway in siPNPT1 HK2 cells, p-PKR inhibitor C16 (0.5 μM, 4 h) dissolved in 0.1% DMSO was used. To knockdown PKR expression, siRNAs was transfected using Lipofectamine RNAi MAX following the manufacturer’s instructions. To suppress mtRNA synthesis, HK2 cells were treated with 0.1 mM of IMT1 for 72 h.

Apoptosis assay

Cell apoptosis was determined using an FITC-Annexin V Apoptosis Detection Kit. Briefly, 2 × 105 cells were resuspended in 0.5 ml binding buffer and incubated with FITC-Annexin V and PI for 15 min in the dark. Data were acquired with a Attune NxT (Thermo Fisher Scientific) flow cytometer and analyzed by FlowJo, and apoptotic cells were identified from the Annexin V-positive, PI-negative fractions. Cell apoptosis in paraffin-embedded kidney sections (4μm thickness) was detected by the TUNEL assay. Tissue sections were subjected to dewaxing and hydration and then to apoptosis analysis using the TUNEL Bright-Green apoptosis detection kit. Quantification of TUNEL staining was determined by counting the percentage of TUNEL-positive tubular cells.

Histological and immunofluorescence analysis

H&E staining of 4-μm-thick formalin-fixed, paraffin embedded kidney tissue sections was performed according to standard protocols. Images were captured by microscopy (Olympus BX53). In each kidney, the numbers of damaged tubules were counted separately in 10 nonoverlap** fields observed at ×400 magnification. Renal tubular injury scores expressed as the percentage of damaged tubules, and the mean values were calculated (GraphPad Prism). For immunofluorescence staining of kidney tissue sections, heat-induced antigen retrieval was performed by heating sections in 1 mM EDTA at 95 °C in a pressure cooker for 20 min and then 20 min of cooling at room temperature. Sections were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in 1× PBS. Sections were incubated for 30 min at room temperature with blocking buffer 5% BSA in 1× PBS and subsequently incubated with primary antibodies including anti-dsRNA mAb J2, anti-PNPT1, anti-AQP1, and anti-podocin antibodies for 3 h. Sections were washed in 1× PBS three times and then incubated with secondary antibodies including goat anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 488, donkey anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor594, donkey anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488, and goat anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 594 antibodies for 1 h at room temperature followed by 3 washes with 1× PBS. The sections were then mounted in Prolong Diamond Antifade Mountant with DAPI. Confocal images were taken using a confocal microscope (Zeiss LSM 880) with ZEN 3.1 blue edition software. Fluorescence intensities were quantified using ImageJ 1.44p software.

RNA FISH

To visualize heavy and light strands of mt-ND5 RNA, RNA fluorescent in situ hybridization (RNA-FISH) was performed using RiboTM Fluorescent In Situ Hybridization Kit. The pretreatment, hybridization, and signal amplification were done following the manufacturer’s instructions. Zeiss LSM 880 confocal microscope was used for visualization. Fluorescence intensities were quantified using ImageJ 1.44p software.

Transmission electronic microscopy (TEM)

Renal cortices were collected and dissected into 1-mm3 pieces and fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde, followed by post-fixation in 2% osmium tetroxide, dehydrated in graded series of acetone and ethanol, and embedded in epoxy resin. Ultrathin sections (80–90 nm) were stained for 15 min in 5% uranyl acetate, followed by 0.1% lead citrate for 5 min. Electron micrographs were obtained and analyzed using a Hitachi 7500 transmission electron microscope.

Western blot analysis

Mouse renal tubules were isolated. Briefly, the renal cortex was cut into small cubes of ~1 mm3 and digested with collagenase D, protease and DNaseI in HBSS for 15 min at 37 °C. The digested tissue was screened through a 100 μm filter. Glomeruli-containing Dynabeads (diameter 4.5 µm) were adsorbed using a magnetic particle concentrator and tubulars were gathered from the supernatant after adsorption. Protein extracts from renal tubules or HK2 cells were resolved by SDS-PAGE before being transferred onto the polyvinylidene fluoride (PDVF) membranes. The membranes were blocked and incubated with primary antibodies against PNPT1, PKR, p-PKR, eIF2α, p-eIF2α, ATF4, COX IV, LaminB1, and α-tubulin followed by 6 washes and incubation with secondary antibodies goat anti-mouse IgG-HRP or goat anti-rabbit IgG-HRP. Protein band intensities were quantified using ImageJ 1.44p software. Uncropped scans of all gels are provided in Source data file with this paper.

Protein synthesis assay

Whole protein synthesis of HK2 cells treated with or without siPNPT1 at 12 and 24 h post-transfection was assayed by Click-iT® Plus OPP Protein Synthesis Assay Kits. Images were taken using a 2-photon laser confocal microscope (Zeiss LSM 880). Mean intensities were quantified using ImageJ 1.44p software.

Detection of cytosolic mt-dsRNAs

HK2 cells (5 × 108) were resuspended in 500 µl buffer containing 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM HEPES, 25 µg/ml digitonin, pH7.4. The homogenates were incubated end-over-end for 10 min to allow selective plasma membrane permeabilization, then centrifuged at 1000 g for 5 min to pellet intact cells. The supernatants were transferred to fresh tubes and spun at 17,000 g for 10 min to pellet any cellular debris, yielding cytosolic preps free of nuclear, mitochondrial and ER contamination. The dsRNAs in cytosolic fraction were immunoprecipitated by J2 antibody followed by PierceTM Classic IP Kit. The dsRNA was then extracted and subjected to strand-specific RT-qPCR analysis. Reverse transcription primers and RT-qPCR primers were designed to target the specific genes (mt-ND4-6, mt-CO1 or mt-CYB) (Supplementary Table. 1). The mt-dsRNA levels were normalized to β-actin mRNA level.

Statistical analysis

Data were presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was performed in GraphPad Prism 8.0. All data were obtained from at least 3 independent experiments. Details of the statistical tests were described in the individual figure legends. Data with P value <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Sample size base on the data in our previous study and a given power (>0.8) using G-power software 3.1.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All relevant data generated for this study were included in the article/Supplementary Material. All the data analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding authors upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Levin, A. et al. Global kidney health 2017 and beyond: a roadmap for closing gaps in care, research, and policy. Lancet 390, 1888–1917 (2017).

Liang, X. et al. Glycogen synthase kinase 3beta hyperactivity in urinary exfoliated cells predicts progression of diabetic kidney disease. Kidney Int 97, 175–192 (2020).

Najafian, B., Kim, Y., Crosson, J. T. & Mauer, M. Atubular glomeruli and glomerulotubular junction abnormalities in diabetic nephropathy. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 14, 908–917 (2003).

Gilbert, R. E. Proximal Tubulopathy: Prime Mover and Key Therapeutic Target in Diabetic Kidney Disease. Diabetes 66, 791–800 (2017).

Khan, S. et al. Lipotoxic disruption of NHE1 interaction with PI(4,5)P2 expedites proximal tubule apoptosis. J. Clin. Invest 124, 1057–1068 (2014).

Nath, K. A. Tubulointerstitial changes as a major determinant in the progression of renal damage. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 20, 1–17 (1992).

Bunnag, S. et al. Molecular correlates of renal function in kidney transplant biopsies. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 20, 1149–1160 (2009).

Schelling, J. R. Tubular atrophy in the pathogenesis of chronic kidney disease progression. Pediatr. Nephrol. 31, 693–706 (2016).

Rosenberger, C. et al. Adaptation to hypoxia in the diabetic rat kidney. Kidney Int 73, 34–42 (2008).

Bhargava, P. & Schnellmann, R. G. Mitochondrial energetics in the kidney. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 13, 629–646 (2017).

He, W. et al. Sirt1 activation protects the mouse renal medulla from oxidative injury. J. Clin. Invest 120, 1056–1068 (2010).

Higgins, D. F. et al. Hypoxia promotes fibrogenesis in vivo via HIF-1 stimulation of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. J. Clin. Invest 117, 3810–3820 (2007).

Kume, S. et al. Calorie restriction enhances cell adaptation to hypoxia through Sirt1-dependent mitochondrial autophagy in mouse aged kidney. J. Clin. Invest 120, 1043–1055 (2010).

Wang, Q. & Carmichael, G. G. Effects of length and location on the cellular response to double-stranded RNA. Microbiol Mol. Biol. Rev. 68, 432–452 (2004).

Lee, J. H. et al. Mitochondrial Double-Stranded RNA in Exosome Promotes Interleukin-17 Production Through Toll-Like Receptor 3 in Alcohol-associated Liver Injury. Hepatology 72, 609–625 (2020).

Lee, C. Y. D. & Yang, X. W. Huntington’s Disease: Genome-wide Neuroprotection Screening Goes Viral. Neuron 106, 4–6 (2020).

Kim, S. et al. Mitochondrial double-stranded RNAs govern the stress response in chondrocytes to promote osteoarthritis development. Cell Rep. 40, 111178 (2022).

Kim, Y. et al. PKR Senses Nuclear and Mitochondrial Signals by Interacting with Endogenous Double-Stranded RNAs. Mol. Cell 71, 1051–1063 e1056 (2018).

Garcia, M. A., Meurs, E. F. & Esteban, M. The dsRNA protein kinase PKR: virus and cell control. Biochimie 89, 799–811 (2007).

Linder, A. & Hornung, V. Mitochondrial dsRNA: A New DAMP for MDA5. Dev. Cell 46, 530–532 (2018).

Darini, C. et al. An integrated stress response via PKR suppresses HER2+ cancers and improves trastuzumab therapy. Nat. Commun. 10, 2139 (2019).

Mounir, Z. et al. Tumor suppression by PTEN requires the activation of the PKR-eIF2alpha phosphorylation pathway. Sci. Signal 2, ra85 (2009).

Linkermann, A. et al. Rip1 (receptor-interacting protein kinase 1) mediates necroptosis and contributes to renal ischemia/reperfusion injury. Kidney Int 81, 751–761 (2012).

Lan, H. Y. et al. Inhibition of renal fibrosis by gene transfer of inducible Smad7 using ultrasound-microbubble system in rat UUO model. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 14, 1535–1548 (2003).

**ao, L. et al. Sustained Activation of Wnt/beta-Catenin Signaling Drives AKI to CKD Progression. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 27, 1727–1740 (2016).

Jang, H. S., Noh, M. R., Ha, L., Kim, J. & Padanilam, B. J. Proximal tubule cyclophilin D mediates kidney fibrogenesis in obstructive nephropathy. Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol. 321, F431–F442 (2021).

Mei, S. et al. Susceptibility of renal fibrosis in diabetes: Role of hypoxia inducible factor-1. Faseb J. 36, e22477 (2022).

Klahr, S. & Morrissey, J. Obstructive nephropathy and renal fibrosis. Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol. 283, 861–875 (2002).

Wu, M. J. et al. Rapamycin attenuates unilateral ureteral obstruction-induced renal fibrosis. Kidney Int 69, 2029–2036 (2006).

Chi, H. H. et al. IL-36 Signaling Facilitates Activation of the NLRP3 Inflammasome and IL-23/IL-17 Axis in Renal Inflammation and Fibrosis. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 28, 2022–2037 (2017).

Dhir, A. et al. Mitochondrial double-stranded RNA triggers antiviral signalling in humans. Nature 560, 238–242 (2018).

Szczesny, R. J. et al. Human mitochondrial RNA turnover caught in flagranti: involvement of hSuv3p helicase in RNA surveillance. Nucleic Acids Res 38, 279–298 (2010).

Borowski, L. S., Dziembowski, A., Hejnowicz, M. S., Stepien, P. P. & Szczesny, R. J. Human mitochondrial RNA decay mediated by PNPase-hSuv3 complex takes place in distinct foci. Nucleic Acids Res 41, 1223–1240 (2013).

Chen, H. W. et al. Mammalian polynucleotide phosphorylase is an intermembrane space RNase that maintains mitochondrial homeostasis. Mol. Cell Biol. 26, 8475–8487 (2006).

Wang, G. et al. PNPASE regulates RNA import into mitochondria. Cell 142, 456–467 (2010).

Piwowarski, J. et al. Human Polynucleotide Phosphorylase, hPNPase, is Localized in Mitochondria. J. Mol. Biol. 329, 853–857 (2003).

Sarkar, D., Park, E. S. & Fisher, P. B. Defining the mechanism by which IFN-beta dowregulates c-myc expression in human melanoma cells: pivotal role for human polynucleotide phosphorylase (hPNPaseold-35). Cell Death Differ. 13, 1541–1553 (2006).

Ding, Y. et al. Autophagy regulates TGF-beta expression and suppresses kidney fibrosis induced by unilateral ureteral obstruction. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 25, 2835–2846 (2014).

Kota, S. K. et al. BPI Fold-Containing Family A Member 2/Parotid Secretory Protein Is an Early Biomarker of AKI. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 28, 3473–3478 (2017).

Hopp, A. K. et al. Mitochondrial NAD(+) Controls Nuclear ARTD1-Induced ADP-Ribosylation. Mol. Cell 81, 340–354.e345 (2021).

Meurs, E. F. et al. Constitutive Expression of Human Double-Stranded Rna-Activated P68 Kinase in Murine Cells Mediates Phosphorylation of Eukaryotic Initiation Factor-Ii and Partial Resistance to Encephalomyocarditis Virus Growth. J. Virol. 66, 5805–5814 (1992).

Patel, R. C., Stanton, P., Mcmillan, N. M. J., Williams, B. R. G. & Sen, G. C. The Interferon-Inducible Double-Stranded Rna-Activated Protein-Kinase Self-Associates in-Vitro and in-Vivo. P Natl Acad. Sci. USA 92, 8283–8287 (1995).

Weinberg, S. E., Sena, L. A. & Chandel, N. S. Mitochondria in the regulation of innate and adaptive immunity. Immunity 42, 406–417 (2015).

Andrejeva, J. et al. The V proteins of paramyxoviruses bind the IFN-inducible RNA helicase, mda-5, and inhibit its activation of the IFN-beta promoter. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 101, 17264–17269 (2004).

Yoneyama, M. et al. The RNA helicase RIG-I has an essential function in double-stranded RNA-induced innate antiviral responses. Nat. Immunol. 5, 730–737 (2004).

Lu, B. et al. Novel role of PKR in inflammasome activation and HMGB1 release. Nature 488, 670–674 (2012).

Bonekamp, N. A. et al. Small-molecule inhibitors of human mitochondrial DNA transcription. Nature 588, 712–716 (2020).

Godin, N. et al. Catalase overexpression prevents hypertension and tubular apoptosis in angiotensinogen transgenic mice. Kidney Int. 77, 1086–1097 (2010).

Schoof, M. et al. Viral evasion of the integrated stress response through antagonism of eIF2-P binding to eIF2B. Nat. Commun. 12, 7103 (2021).

Wang, H. et al. Double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase deficiency protects the heart from systolic overload-induced congestive heart failure. Circulation 129, 1397–1406 (2014).

Lin-Chao, S., Chiou, N. T. & Schuster, G. The PNPase, exosome and RNA helicases as the building components of evolutionarily-conserved RNA degradation machines. J. Biomed. Sci. 14, 523–532 (2007).

Alodaib, A. et al. Whole-exome sequencing identifies novel variants in PNPT1 causing oxidative phosphorylation defects and severe multisystem disease. Eur. J. Hum. Genet 25, 79–84 (2016).

Matilainen, S. et al. Defective mitochondrial RNA processing due to PNPT1 variants causes Leigh syndrome. Hum. Mol. Genet 26, 3352–3361 (2017).

Alexander, R. T., Rievaj, J. & Dimke, H. Paracellular calcium transport across renal and intestinal epithelia. Biochem Cell Biol. 92, 467–480 (2014).

Zhou, D. et al. Tubule-specific ablation of endogenous beta-catenin aggravates acute kidney injury in mice. Kidney Int 82, 537–547 (2012).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by grants from National Key R&D Program of China (2018YFA0507100, K.Z.) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (82170692, K.Z.). Kidney samples were obtained from Renal Biobank of National Clinical Research Center of Kidney Diseases, Jiangsu Biobank of Clinical Resources, a part of The Open Project of Jiangsu Biobank of Clinical Resources (JSRB2021-03).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.Z., Z.L. and L.L. conceived and designed the experiments; Y.Z., M.Z., W.W., S.Q., M.L., W.Y., H.L. and W.R. performed experiments; Y.Z. and K.Z. analyzed data; Z.L., C.Z., M.Z. and X.Z. contributed technical or material support; K.Z. and Y.Z. wrote the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declared no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Jeffrey Schelling and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhu, Y., Zhang, M., Wang, W. et al. Polynucleotide phosphorylase protects against renal tubular injury via blocking mt-dsRNA-PKR-eIF2α axis. Nat Commun 14, 1223 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-36664-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-36664-0

- Springer Nature Limited