Abstract

Copper-based materials can reliably convert carbon dioxide into multi-carbon products but they suffer from poor activity and product selectivity. The atomic structure-activity relationship of electrocatalysts for the selectivity is controversial due to the lacking of systemic multiple dimensions for operando condition study. Herein, we synthesized high-performance CO2RR catalyst comprising of CuO clusters supported on N-doped carbon nanosheets, which exhibited high C2+ products Faradaic efficiency of 73% including decent ethanol selectivity of 51% with a partial current density of 14.4 mA/cm−2 at −1.1 V vs. RHE. We evidenced catalyst restructuring and tracked the variation of the active states under reaction conditions, presenting the atomic structure-activity relationship of this catalyst. Operando XAS, XANES simulations and Quasi-in-situ XPS analyses identified a reversible potential-dependent transformation from dispersed CuO clusters to Cu2-CuN3 clusters which are the optimal sites. This cluster can’t exist without the applied potential. The N-do** dispersed the reduced Cun clusters uniformly and maintained excellent stability and high activity with adjusting the charge distribution between the Cu atoms and N-doped carbon interface. By combining Operando FTIR and DFT calculations, it was recognized that the Cu2-CuN3 clusters displayed charge-asymmetric sites which were intensified by CH3* adsorbing, beneficial to the formation of the high-efficiency asymmetric ethanol.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Electrochemical conversion of carbon dioxide into value-added products using sustainable energies is environmentally friendly and economical approach1. As well known, C2+ hydrocarbons or oxygenated compounds such as ethanol (C2H5OH), ethylene (C2H4) and n-propanol (n-C3H7OH) with remarkable energy densities have more value for solving the energy crisis2. However, complex product selectivity limits the development and application of carbon dioxide reduction. The origin of this selectivity toward C2+ hydrocarbons has been a prominent topic of study recently and has been intensely debated3,4,5,6. Copper-based materials are absolutely effective and promising catalysts for the reduction of carbon dioxide to multi-carbon products3. Previous works indicated that both the catalysts and substrates could affect the local structure and the electronic state of active sites, and then modify the reaction pathway and catalytic mechanism4,5. Many strategies have been developed to modify or optimize the copper-based catalysts for improving the multi-carbon products selectivity, such as adjusting the surface morphology4,5,7,8,9,10,11,12,13, do** metals or non-metals14,15,16,17,18, building nanostructures19,20,21, or designing single active sites22,23,24,25.

Despite tremendous effort has been paid, further advances are still needed to understand the structure-activity relationship (SAR) and efficient conversion CO2 to multi-carbon products especially for high economy asymmetric C2+ products (e.g., ethanol). Therefore, the design of catalysts that selectively produce ethanol via electrochemical CO2RR were supposed to focus on minimizing three competing reaction pathways which reduced the faradaic efficiency (FE) of asymmetric ethanol by consuming electrons and protons, the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER), C1 product formation (e.g., CH4, HCOOH) and other symmetrical C2 product formation (e.g., ethylene). However, little is known about the structure-activity relationship, extraordinarily to explain the catalyst structure changes with the product changes under different potential. Hence, it is urgent to build the structure-activity relationship between atomic structure and products for designing electrocatalysts.

Here we synthesized CuO clusters supported on nitrogen-doped carbon nanosheets (Cu/N0.14C) as dispersed electrocatalysts, achieving high-performances CO2 reduction that are superior to CuOx catalysts in terms of stability, activity and selectivity. The prepared Cu/N0.14C catalyst with appropriate nitrogen content displayed high C2+ products Faradaic efficiency of 73% which includes ethanol FE of 51% at the potential of −1.1 V vs. RHE with a current density of −14.4 mA/cm−2 in 0.1 M KHCO3 electrolyte. Moreover, it exhibited superb long-term CO2 electroreduction durability over 10 h. The well-defined self-reconstruction for the active sites of Cu/N0.14C also facilitate the in-depth mechanistic understandings from complementary Operando Spectroscopy (XAS, XPS and FTIR), XANES simulations and theoretical calculations to present the atomic structure-activity relationship between the ethanol selectivity and in situ dynamic structure (local structure, electronic structure and the adsorbed intermediates), that would benefit the recognition for the CO2RR process.

Results and discussion

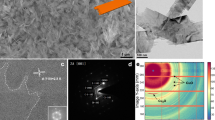

Structure characterization of the Cu/NxC

In a typical procedure, copper phthalocyanine and dicyandiamide were continuously mixed in ethanol and dried. Subsequently, the dried mixture was pyrolyzed at different temperatures for a series of Cu/NxC samples with different nitrogen content (x = 0.14, 0.11, 0.02, 0, x is mass contents ratio of nitrogen to carbon). The linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) curves demonstrated that the activity of Cu/N0.14C was better than other contrast samples with maximum current density. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) revealed that Cu/NxC displayed a nano flake structure without obvious large-scale particles on the surface (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. 1). The nanosheet structure was further confirmed by atomic force microscopy (AFM), and the corresponding height profiles of the scans showed a thickness of about 0.6 nm (Supplementary Fig. 2). The N species in the samples could prevent Cu atoms from aggregating excessively and ensured the atomic dispersion of Cu species. As we found in Supplementary Fig. 3, Cu nanoparticles (about 2–3 nano) were observed in the sample Cu/C (without N). High angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM), which can be clearly observed in the atomic phase, revealed that the copper atoms of Cu/N0.14C agglomerate into clusters without an obvious lattice (Fig. 1b). Elemental map** by Energy Dispersive Spectrometer (EDS) (Fig. 1c) demonstrates that nitrogen is uniformly dispersed within the carbon matrix. X-ray diffraction (XRD) revealed only a broad peak from the (002) of the Cu/N0.14C and N0.14C (Fig. 1d), however the Cu/C showed totally different peaks which could belong to a pure metallic copper (PDF#04-0836). The electron diffraction pattern of Cu/N0.14C revealed it was amorphous material in Supplementary Fig. 4. To further study the electronic structure of the catalysis, Cu K-edge X-ray absorption spectroscopy, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) and soft-X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) were carried out as shown in Fig. 1e–g and i and Supplementary Fig. 5. The Cu 2p3/2 XPS fitting curves revealed that Cu was mainly +1 and +2 valence in Cu/N0.14C26,27. The Cu L3M45M45 Auger electron spectroscopy (AES) showed no distinct peak around 918.5 eV which indicated that no Cu0 existed on the surface. The N K-edge presented four obvious resonances (Fig. 1i) assigned peak A1, A2, and A3 to pyridine-like, cyanide-like, and graphite-like N, respectively, whereas A4 at ∼407 eV is attributed to the transition from N 1s core states to N−C σ* bonds28. Obviously, peak A3 of Cu/N0.14C shifts negative energy which indicated the charge transfer had occurred compared with that of N0.14C while other peaks keep the same position, indicating graphite-N formed a chemical bond with Cu sites29. The C K-edge XAS spectra in Supplementary Fig. 5 showed no difference between Cu/N0.14C and N0.14C, excluding formation of the Cu−C bond. Thus, we could conclude that Cu sites only bond to graphite-like N, in Cu/N0.14C.

a TEM image of Cu/N0.14C. b HAADF-STEM image of Cu/N0.14C. c EDS of Cu/N0.14C. d XRD of Cu/N0.14C, Cu/C and NC. e Cu K-edge XANES spectra of Cu/N0.14C with the references. f FT-EXAFS spectra of Cu/N0.14C with the references. g XPS analysis of the Cu 2p3/2 for Cu/N0.14C and Cu/C. h AES analysis of the Cu L3M45M45 for Cu/N0.14C and Cu/C. i N K-edge XANES spectra of Cu/N0.14C and N0.14C.

X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) measurements were employed to further investigate the electronic structure and geometric structure of the Cu/N0.14C. Fig. 1e showed the Cu K-edge XANES spectra of the Cu/N0.14C together with the references of CuO, Cu2O and Cu foil. The absorption edge of the Cu/N0.14C was between the Cu2O and CuO, indicating that the oxidation state of the copper species is in the intermediate valence state between +1 and +2. The feature of XANES at 8986 eV and 8997 eV for Cu/N0.14C resembled the mixture dominated by CuO with a little contribution by Cu+ or Cu0 complex. The Fourier-transformed (FT) k3-weighted EXAFS oscillation in Fig. 1f also showed the disappearance of the feature for Cu–Cu in R space in Cu/N0.14C with simultaneous appearance of the peak at 1.5 Å for Cu−O/N. The fitting result displayed that the Cu−O/N bond length is 1.93 Å with the coordination number (CN) 3.4, (Supplementary Figs. 6, 7 and Table 1) indicating that Cu ions in the as-synthesized catalysts were predominately in the form of CuO clusters coordinated with four oxygen atoms. Notably, the coordination number of Cu−O/N is lower than that of the CuO (CN = 4) with a litter shorter bond length (1.93 Å) (the bond length in CuO is 1.95 Å) suggesting that Cu species with a definite Cu–O/N coordination-unsaturated structure (CN < 4, bond length <1.95 Å) existed. Note that TEM and EDX results showed CuO clusters were uniformly dispersed and anchored on the N-doped carbon nanosheets support. To further explore the N-doped that influenced CO2RR activity, XANES and FT-EXAFS of Cu/C without the N-do** was plot in Supplementary Fig. 8. The XANES of the Cu/C indicated that the Cu ions were reduced to metallic Cu. The FT-EXAFS data also showed the peak for Cu–Cu in R space with the weak peak at 1.5 Å for Cu–O revealing that the copper in Cu/C agglomerated into larger metallic particles with a copper oxides surface in the air (more detail in Supplementary Figs. 9, 10 and Table 2). Our study indicated that N-doped promotes the dispersion of CuO clusters in the as-synthesized catalysts and played the critical role in improving FE for direct CO2-to-ethanol electrochemical conversion. These results agreed well with XRD and HAADF–STEM results. The structure of the Cu/N0.14C is further discussed by operando XAS.

Electrochemical characterization

The electrochemical CO2RR activity of Cu/NxC catalysts were evaluated in CO2-saturated 0.1 M KHCO3 solution. Linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) curves (Fig. 2a) demonstrated that the activity of Cu/N0.14C was better than other contrast samples with lowest onset potential and maximum current density. This suggested that the increase in nitrogen content is helpful but limited to improve the activity. Versus Cu/N0.14C catalysts, the NC catalyst has little activity. Fig. 2b showed the product selectivity of CO2RR of Cu/N0.14C catalyst. The main products formed at low potential were CO and H2. At −0.7 V (versus the reversible hydrogen electrode, RHE), hydrocarbons such as ethylene (C2H4) and methane (CH4) started to form, and the selectivity of CO and H2 decreased. The product of ethanol (C2H5OH) was first detected at −0.8 V vs. RHE. Subsequently, the faradaic efficiency (FE) of C2+ products continuously increased in the range −0.8 V to −1.1 V. At −1.1 V, the maximum FE of ethanol is 51% with a current density of −14.4 mA/cm−2 and the total C2+ products FE is up to 73%. We also gave the each product partial current density of Cu/N0.14C catalyst in Fig. 2c. The LSV curves of Cu/N0.14C in N2 afignd CO2 were measured, respectively, in Fig. 2d. In CO2-saturated 0.1 M KHCO3 solution, the Cu/N0.14C displayed high activity. Fig. 2e showed that H2, C1 and C2+ products distributions of five catalysts. Cu/NxC catalysts truly boosted the product selectivity of CO2RR. We further evaluated the stability of Cu/N0.14C for CO2RR by a long-term experiment of 10 h. Both the partial current density and FE of C2+ products lightly decreased (Fig. 2f), that demonstrated good stability. There were no structural changes of Cu/N0.14C after long-term CO2RR electrolysis, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 11.

Operando XAS, SR-FTIR Spectroscopy and Quasi-in-situ XPS-AES results

Studying the atomic structure-activity relationship of CO2RR catalyst under operando conditions is crucial to reveal the intrinsic reactive mechanism. In order to identify the realistic catalytic centers of Cu/N0.14C, operando XAS study were employed to directly monitor its catalytic behavior. We first collected ex-situ XAS data of the fully activated Cu/N0.14C. When Cu/N0.14C was soaked into the KHCO3 solution at open circuit (OC), no obvious structural change was observed from the XANES in Supplementary Fig. 12. Operando XAS spectra recorded approximately every 10 min. There were drastic changes taking place in the sample at the very beginning when the potential was altered. Every spectrum was measured twice after the potential was kept constant for 30 min. XANES and derivative of XANES spectra under the altered potential were plotted in Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 13. The oxidation state of Cu was estimated by comparing the energy position of the absorption edge. It could be clearly seen that XANES dramatically changed with the decreased applied potential indicating that this was a potential-dependent process. The gradual shift of the absorption edge to low energy side revealed a fall of the Cu valence state. An obvious critical potential at −0.8 V vs. RHE could be identified. The valence state of copper remained between +1.0 and +2.0 above this potential. Notably, there was a crude transfer to +1.0 at this critical potential. Below −0.8 V vs. RHE, Cu ions gradually get more deoxidized. Especially, the position of absorption edge was in the middle of Cu foil and Cu2O when the potential was below −1.1 V, illustrating that the copper ions were nearly in averaged valence state of about +0.5. The changes of the atomic local structure around copper ions during CO2RR were captured by FT-EXAFS, as shown in Fig. 3b. Wavelet transforms for the k3-weighted Cu K-edge EXAFS signals at OC, −1.1 and −1.4 V vs. RHE were plot in Fig. 3c. Under open-circuit condition, FT-EXAFS data showed only one peak located at ~1.5 Å which is the typical scattering feature of Cu–N/O coordination. The FT EXAFS fitting results in Supplementary Figs. 5, 6 and Table 1 showed that CN of O/N atoms to Cu atoms was about 3.4 with an average bond length of 1.93 Å, without the Cu–Cu bond contribution. The Cu–O/N bond intensity slight decreased at −0.6 V vs. RHE. No C2+ products are formed at this stage in Fig. 2c. Once applying the potential of −0.8 V vs. RHE, the intensity of the scattering peak extremely descended with an additional peak at ~2.4 Å. This is a typical scattering feature of the Cu–Cu bond. The conversion of CO2-to-ethanol reaction occurred concurrently. The intensity of Cu–O/N scattering peak further descended with the increasing of the Cu–Cu bond as the potential decreased. Moreover, the Cu–O/N peak intensity stabilized and the Cu–Cu bond slowly increased with the potential further decreasing to −1.1 V vs. RHE. The FT EXAFS fitting results (Fig. 3d, Supplementary Figs. 5, 6 and Table 1) indicated that the coordination number of the first Cu–O/N shell gradually decreased from 3.4 to 2.0 along with decreasing potential from OC to −1.4 V vs. RHE. In addition, the average Cu–O/N bond length slightly decreased. The coordination number of the Cu–Cu bond increased to 2.7 with a bond length of 2.53 Å, slightly shorter than that in Cu foil. The FT-EXAFS analyses are in agreement with the XANES data. Note that at −1.1 V vs. RHE with the maximum FE of ethanol, the metallic Cu–Cu coordination number was 2.0 and the CN of the Cu–O/N dropped down to 2.3 concurrently.

a Cu K-edge operando XANES of Cu/N0.14C from OC to −1.4 V vs. RHE in 0.1 M KHCO3. b Operando FT-EXAFS of Cu/N0.14C. c Wavelet transforms for the k3-weighted Cu K-edge EXAFS signals at OC, −1.1 V and −1.4 V vs. RHE during the CO2RR. d The relationship of Cu/N0.14C absorption edge, CN of first shell, CN of second shell and the potential. e Operando FT-EXAFS of Cu/N0.14C after the applied potential was switched off and other conditions remained unchanged. f Proposed scheme for the reversible formation of the catalytically active Cun–CuN3 cluster based on operando XAS and Quasi-in-situ XPS analysis (rufous, O; gray, C; purple, N; blue, Cu bond to both N and Cu; green, Cu just bond to Cu). All potentials are normalized to RHE.

The transformation from CuOx to Cu0 studied by operando XAS during electrochemical CO2RR have been widely reported30,31,32. However, Cu–Cu coordination number, extracted from EXAFS data fitting was usually larger than 8 with the disappearance of Cu–O bond, indicating that Cu nanoparticles formed with average sizes more than 1nm33. In this work, operando XANES spectra revealed that Cu/N0.14C would not transfer to Cu0 totally and FT-EXAFS spectra showed Cu–N/O bond becoming steady with CN of 2.0. The stability of Cu–N coordination has been proved during electrochemical CO2RR34. These results suggested CuO clusters have almost reduced, leaving only Cu–N bond of the CuNx. XAFS is the technique measuring average values over all Cu species. Therefore, the fitting coordination number of Cu–N (CN = 2.0 at −1.4 V vs. RHE) was lower than the coordination number of the true active sites since a large part of Cu atoms bond to another Cu atoms (Cu–Cu CN > 2). On the other hand, considering that a definite Cu–N coordination-unsaturated structure (CN < 4) existed in Cu/N0.14C, we suggested that Cu–N CN of the remaining CuNx is 3, x = 3. Moreover, EXAFS fitting results also indicated the Cu coordination shell switched from Cu–O to Cu–Cu with an unusual low coordination number of 2.0 at −1.1 V vs. RHE, with the maximum FE of ethanol. There are two possible structures of the in situ generated Cu species of Cu/N0.14C, according with the Cu–Cu CN of 2.0. One is that the formation of ultrasmall Cu moiety, Cun, where n = 335, while the other one is a mixture of CuN3 sites and Cu metal particles.

We further integrated two evidence to prove the formation of the Cu3 moiety rather than metal particles. Firstly, we found that the potential-dependent transformation was reversible and in situ generated Cu species were highly unstable and could be easily oxidized in the absence of the applied potential. As shown in Fig. 3e and Supplementary Fig. 14, an operando XAS was performed on this sample after the applied potential was switched off and other conditions remained unchanged. It could be obviously seen that Cu–O/N bond increased, with Cu–Cu bond disappeared concurrently, indicating that the coordination environment reversed from Cu–Cu shell to Cu–O/N shell. Notably, the Cu–O/N bond was still lower than that of the initial fully activated sample. At last, the KHCO3 solution was poured out and the catalyst was in air atmosphere, and ex-situ XAS was performed on this sample. Its spectral shape was identical to that of the initial fully activated sample, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 15, suggesting the Cu species remained to be oxidized and dispersed in the air. This result agreed well with HAADF–STEM results after CO2RR electrolysis in Supplementary Fig. 11. The conversion process of the Cu/N0.14C catalyst was shown in Fig. 3f. On the other hand, we preformed operando XAS on the Cu/C in Supplementary Fig. 16. The XANES and FT-EXAFS of Cu/C were mostly unchanged, verifying the Cu metal particles were very stable and could not be easily oxidized. Therefore, we could rule out the existence of Cu metal particles possibility.

Secondly, we carried out Quasi-in situ x-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) and Auger electron spectroscopy (AES) analysis to prove the valence of Cu species of Cu/N0.14C remain at +1 without Cu0 under the altered potential. The Quasi-in situ XPS and AES results were shown in Fig. 4a, b. The Cu/N0.14C showed two peaks at 934.6 eV and 932.2 eV, which corresponded to Cu2+ and Cu+/Cu[0 26,27. The peak at 934.6 eV disappeared at the −1.1 V vs. RHE, which indicated the Cu2+ was reduced during the CO2RR process. The peaks around 932 eV still remained. To verify the valence of the Cu, AES was employed to distinguish Cu+/Cu0 species. The peaks around 916.5 eV showed a little shift indicating that the sample would retain the valence at +1 during the CO2RR process36,37. The XPS detected the valence state information with depth sensitivity of 1–10 nm38. Therefore, there are no Cu metal particles existing under the electrochemical conditions. Notably, the Cu AES shifted to the higher kinetic energy with the potential reduced, indicating fewer electrons on average Cu were transferred to the nitrogen-doped carbon support of the −1.2 V vs. RHE. The catalysis electron configuration would obviously affect the adsorption of the non-polar molecule, which played an important role during the reduction process39,40. Probably, the ethanol productivity declined at −1.2 V vs. RHE, because the larger cluster could lead to the Cu0 electron configuration increasing32, a Quasi-in-situ XPS of the Cu 2p 3/2 for Cu/N0.14C. b Quasi-in-situ AES of the Cu L3M45M45 for Cu/N0.14C. c Comparison between the Cu K-edge XANES experimental spectra (red line) and the theoretical spectra (black line) calculated with the Cu2-CuN3 cluster. d Operando SR-FTIR of Cu/N0.14C. Electron density difference plot of the e Cu2–CuN3 cluster, f Cu3–CuN3 cluster. Blue and yellow represented the electron accumulation and deletion, respectively. The balls in gray, purple, blue and white represented C, N, Cu, and H atoms, respectively. All potentials were normalized to RHE.

Hence, we can consequently conclude that the Cu–Cu bond of the operando spectroscopy was from in-situ generated ultrasmall Cu moieties, Cun, under the electrochemical conditions, where n = 3 at −1.1 V vs. RHE. Three Cu atoms chemically bonded to each other with the Cu–Cu coordination number of 2 and one Cu atom bonded to three graphite-like N, forming the Cu2–CuN3 moiety, as shown in Fig. 3f. Such Cu3 moieties which are similar to copper clusters44 have geometric shapes of equilateral triangles, and anchored on the N-doped carbon nanosheets support. The Cu–N bonds play an important role to disperse and anchored the Cu3 moiety uniformly. Moreover, the coordination number of Cu–Cu increased to 2.6 with the potential decreased to −1.2 V vs. RHE, suggesting the Cu4 appeared with tetrahedron configuration of the Cu3-CuN3 moiety and the ethanol productivity declined accordingly. Notably, the in-situ generated Cun–CuN3 cluster can’t exist without the applied potential. Furthermore, one CH3* was adsorbed to one Cu atom according to operando FTIRS results in the next discussion. Therefore, there are the other two oxygen atoms which were adsorbed to another Cu atom, because of the average Cu–N/O coordination number ~2. The cluster was shown in Supplementary Fig. 18. The theoretical XANES spectrum was also calculated to confirm that it was the active site based on convolution results for every considered model around each Cu atom. It could be found that the simulated result for this model could reproduce the main features of the experimental XANES at −1.1 V vs. RHE well in Fig. 4c. Two oxygen atoms may be from the adsorbed groups, such as OH*, OCHO*(or CO2), as shown in Supplementary Fig. 19a, c. The experimental spectra were both properly reproduced in Supplementary Fig. 19b, d. The simulated spectra were similar to the spectrum that was calculated without the adsorbed groups. A slight change in the structure of the 2nd shell does not significantly affect the simulated XAFS spectrum, especially for the H atom. On the other hand, the XANES spectra of the references with different local structures were used to compare with XANES of the Cu/N0.14C at −1.1 V vs. RHE and rule out Cu–N2 site, Cu–N3 site with trigonal planar geometry, Cu–N4 sites (including tetrahedral geometry, square planar geometry and Cu–N3 with CH3*) and different sizes Cu nanoparticles as shown in Supplementary Figs. 20–23. We also tried linear combination fitting (LCF) of XANES of Cu NPs with different sizes and various Cu–N4 sites, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 24. We could not obtain a fitting spectrum which was matched with operando XANES at −1.1 V vs. RHE. The main features of LCF result were notable different from that of operando XANES. Therefore, the possibility of combining for Cu NPs with different sizes and various Cu–N4 sites could be excluded.

In order to verify that Cu2–CuN3 clusters in-situ generated are truly metastable catalyst and the potential-dependent reversibility was real chemical reaction, the freeze-quench approach was used to freeze the redox state and local structure of the catalyst and measured XAFS data at liquid helium temperatures (18 K), as shown in Supplementary Fig. 25a. The X-ray edge energy as well as the spectral shape of the freeze-quench and operando spectra do not differ significantly in Supplementary Fig. 25b–d. This comparison verified that the freeze-quench and operando method access the same electrochemical state of the Cu/N0.14C (same oxidation state and local structure). The spectra which were measured for three times could be perfectly overlapped in Supplementary Fig. 25e–g. These results indicated that Cu2–CuN3 clusters oxidized without the applied potential was the chemical reaction and Cu2–CuN3 clusters in-situ generated material were truly metastable catalysts.

Overall, Operando XAS study revealed that a transformation from Cu/N0.14C to unique ultrasmall Cun moiety and presented the structure-activity relationships of this catalyst, indicating the in-situ generated Cu2–CuN3 cluster is the optimal site for CO2 reduction to ethanol.

To further reveal the key adsorbed intermediates in the catalytic reaction, we carried out Synchrotron radiation operando Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (SR-FTIRS). No obvious absorption band was observed on scanning the applied potential ranging from −0.1 V to −0.7 V vs. RHE (Fig. 4d). Interestingly, distinct vibration features were observed at 1450 cm−1 when applied potentials were lower than −0.7 V vs. RHE, which could be assigned to the antisymmetric methyl groups vibration of CH3* 45,46, an important intermediate for C2 formation rates. Furthermore, when the applied potential was below −1.1 V vs. RHE, two new bands at ~ 1780 cm−1 and 1920 cm−1 could be ascribed to the surface-bound C=O species12,47 and electrogenerated CO bound to copper surface12,48 suggesting H* radicals were consumed by other products at −1.2 V vs. RHE, which was consistent with the electrochemical results (Fig. 2c). The FE of the ethanol reached a high point at −1.1 V vs. RHE and then decreased obviously at lower potential to accompany the hydrogen rate increased. The FE of ethanol reversed at −1.2 V vs. RHE may be due to the Cu cluster enlarging that lead to the competing reaction of HER and CO2RR hydrogenation to CH4 enhancing, which blocked the CO2 to ethanol20c, f, g, h. The supported CuN3, Cu–CuN3, Cu2–CuN3 and Cu3–CuN3 models with a Cu bonding with three N atoms on N-doped carbon nanosheets which were proposed to be the structure of active sites with the applied potential and represents the growth of Cu clusters that may be the active site for the formation of ethanol according the results of operando XAS analysis. The reaction pathway of CO2RR to CH3CH2OH for the Cu2–CuN3 cluster was investigated combined by the computational hydrogen electrode approach as shown in Fig. 5a, b, Supplementary Fig. 28, and Supplementary Data 1–1352. The *OCHO mechanism was preferred for our catalysts than the *CO mechanisms, due to the production of CO was suppressed along with the formation of ethanol at the potentials below −0.8 V as shown in Fig. 2b. CO2 molecules interact with two exposed Cu atoms, respectively, forming coadsorbed (*OCHO + *OCHO) (State 3). One adsorbed *OCHO was firstly reduced to form *CH3 + *OCHO (State 9), and then the other *OCHO was reduced to construct *CH3 + *OCH2 (State 12), that went through the C–C bond formation to CH3CH2OH. Similar reaction processes based on *OCHO mechanism were considered for Cu3–CuN3, as well as CuN3 and Cu–CuN3 which contained only one active Cu site, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 29. The calculated overpotential (−0.501 V) for Cu2–CuN3 cluster was much lower than that of CuN3 (−1.685 V), Cu–CuN3 (−1.368 V) and Cu3–CuN3 (−0.699 V), implied that the Cu2–CuN3 observed by operando XAS is the real active site for reduction of CO2 to ethanol, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 30. Furthermore, there were relatively high energy barriers for State 8 → 9 (−0.501 eV) and State 11 → 12 (−0.467 eV) in the reaction process of Cu2–CuN3, both of which containing –CH3 and easy to be detected in accordance with our FTIR results.

a Reaction progress of CO2 to CH3CH2OH on the Cu2–CuN3 at 0 V and −0.501 V applied potential. The * showed the reaction site. The state with the highest energy barrier (0.501 eV) is 8 → 9. All states involving the transfer of the (H+ + e−) pair were electrochemical reaction states, except for the 12 → 13 state (CH3* + OCH2* → OCH2CH3*), which was the C–C bond formation and not influenced by applied potential. b Local structures of the active site and intermediate state. The balls in brown, blue, red, gray and white represent Cu, N, O, C, and H atoms, respectively.

The hydrogen evolution reaction is a competing reaction with CO2RR53,54. Therefore, the competing relationship between CO2RR and HER should be considered. The adsorption energy was calculated to further investigate the difference between Cu2–CuN3 and Cu3–CuN3. The adsorption energy of H* showed that the Cu3–CuN3 model (−0.36 eV) had a much lower energy than the Cu2–CuN3 model (+0.15 eV). The CO2 adsorption energy for Cu2–CuN3 and Cu3–CuN3 has been calculated and the result shown that the adsorption energy of CO2 for Cu2–CuN3 and Cu3–CuN3 are +0.24 eV and +0.18 eV, respectively, implying the adsorption capacities for Cu2–CuN3 and Cu3–CuN3 are close. However, the corresponding adsorption energy is +0.15 eV (Cu2–CuN3) and −0.36 eV (Cu3–CuN3), respectively, indicating the adsorption capacities of H for Cu3–CuN3 are much stronger than that for Cu2–CuN3. These results shown the adsorption processes of both CO2 and H at the Cu2–CuN3 are non-spontaneous processes. On the contrary, for Cu3–CuN3, the adsorption of the H is spontaneous process, while the adsorption of CO2 is still non-spontaneous process, illustrating the H adsorption is advantage state for the competing reaction. Therefore, the larger amounts of H were adsorbed on the Cu3–CuN3 sites, which preempted the adsorption sites of CO2 and reduced the amount of ethanol produced. It corresponded with the competing reaction of H2 and CH4 increasing when the potential decreased.

CH3* was the key intermediate for C2+ formation rates and it occurred when the potential decreased to −0.6 V vs. RHE. This result suggested the rate-determining steps (RDS) altered when the potential at decreased to −1.2 V vs. RHE, combining the FTIR results in Fig. 4d. To further analysis why RDS changed during the reaction, the different charge density for Cu2-CuN3 (with/without CH3*) and Cu3-CuN3 (with/without CH3*) was calculated as showing in the Fig. 4e, f and Supplementary Fig. 31. The charge density differential diagram indicated the nonbonding Cu atoms in the Cu2–CuN3–CH3 got 0.15 e− and the charge accumulation occurred. These results showed that charge-asymmetry effected intensified by CH3* adsorption. Due to the charge accumulation, a polarization electrical field was presented that could modulate the CO2 reduction reaction and reduce the thermodynamic energy barrier for the reaction55. The electron-rich Cu atoms enhanced the boundary oxygen sites of the adsorbed CO2, which protected the oxygen end from being protonated and occupied the valence electron of carbon to avoid the C=C double bond formation56.

Conclusions

In summary, we systematically investigated a catalyst in which CuO clusters are supported on nitrogen-doped carbon nanosheets (Cu/N0.14C) for efficient CO2 electroreduction. The catalysts delivered high C2+ products FE (~73%), which included an ethanol FE of 51% at the potential of −1.1 V vs. RHE and the current density of −14.4 mA/cm−2 in 0.1 M KHCO3 electrolyte. Operando XAS and XPS results revealed a potential-dependent structure transformation from CuO cluster to Cun–CuN3 moiety, which is a reversible process. Once Cu2–CuN3 clusters have been formed at −1.1 V, CO2 conversion to ethanol occurs with the maximum FE, indicating the Cu2-CuN3 cluster is the optimal site. The N-do** played an important role to disperse the reduced Cun cluster uniformly and adjust charge distribution between metal atoms and substrate. Operando FTIR and theoretic calculations results demonstrated that CH3* was the major intermediates and Cu2–CuN3 clusters were charge-asymmetric sites that are intensified by CH3* adsorbing. The charge-asymmetric sites are responsible for the outstanding asymmetry ethanol formation. Overall, our findings suggest a strategy engineering the pre-catalysts to modulate the electron transfer and in-situ generate ultrasmall metal clusters anchored on the substrate as high dispersion asymmetric sites, which is the key factor to facilitate the formation of asymmetric products. It would extend to the single-atomic site, oxide composite structure, and metal-support effect. These catalysts have great potential to exhibit novel catalytic properties such as more efficient catalytic performance and higher selectivity compared to the single atom catalysts and oxide catalysts.

Methods

Preparation of Cu/NxC and the comparison samples

Typically, 100 mg copper phthalocyanine and 1.0 g dicyandiamide were continuously mixed in ethanol and entirely dried. Subsequently, the dried mixture was pyrolyzed for 2 h in the N2 atmosphere at different temperature to obtain a series of Cu/NxC samples with different nitrogen content (x = 0.14, 0.11, 0.02, corresponding pyrolysis temperature at 800 °C, 900 °C, 1000 °C, respectively. x is mass content ratio of nitrogen to carbon). Collect obtained black powder after pyrolysis and directly used for further characterizations and catalytic performance test. Cu/C was prepared with copper chloride and trimesic acid. The pyrolysis temperature was 800 °C and other synthesis conditions were the same as above.

Characterization

TEM images were carried out by the JEOL JEM-2100F microscope (200 kV). AFM was obtained on SPM-960 AFM. Typically, small amount of sample was ultrasonically dispersed in the aqueous solution. For AFM measurement, 10 μL of the completely dispersed solution was carefully dropped on a flat mica sheet, and then placed it in a fume hood to air dry. For TEM, 10 μL of the dispersed solution prepared above was dropped on a copper mesh with carbon support film. EDS elemental map** and HAADF-STEM were characterized by a JEOL ARM-200 microscope (200 kV) with a probe spherical aberration corrector. X-ray powder diffraction (XRD) spectra were observed by RigakuTTR-III XRD of Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5418 Å). XPS spectra were acquired on a PerkinElmer Physics PHI 5300 spectrometer57.

Electrochemical measurements

Electrochemical measurements were accomplished in a gas-tight H-type cell at CHI 760E electrochemical workstation (Shanghai Chenhua, China). For preparation of the working electrode, 2 mg of the catalyst was dissolved in 500 μl solution (including 10 μl Nafion solution (5 wt %) and deionized water/ethanol (volume ratio, 1:4)) to form a well-dispersed catalyst ink. Furthermore, we dropped 10ul ink on the glassy carbon electrode. The catalyst loading is about 0.2 mg/cm2. The Ag/AgCl electrode and platinum plate were employed as the reference electrode and counter, respectively. The cathodic chamber and anodic chamber were separated by Nafion 117 membrane. All the potential was reported versus RHE. The conversion between different electrode potentials used the following formula: ERHE = EAg/AgCl + 0.197 V + 0.0591 × pH. LSV (the scan rate of 10 mV·s−1) and CV experiments (50 mV·s−1) were implemented to test the catalytic performance in CO2-saturated 0.1 M KHCO3 electrolyte, respectively57. Comparison of CO2RR activities for the other catalysts were shown in Supplementary Table 3.

Operando XAFS Measurements

The computer-controlled electrochemical analyzer was used to conduct electrochemical measurements. The catalyst modified carbon paper, Pt plate and Ag/AgCl (KCl-saturated) electrode were employed as the working electrode, counter electrode and reference electrode, respectively. The plexiglass electrochemical cell which had the flat wall with a circular hole of 15 mm diameter. was applied for operando XAFS measurements. Cu/NxC catalyst coated carbon paper contacted with the copper slip and the catalyst layer faced inward. Afterwards we poured KHCO3 solution into the cell which was connected to the electrochemical station with the copper tape. The organic glass upper cover of the cell with the Ag/AgCl reference electrode was used to fix the distance between reference electrode and working electrode from start to finish57. Operando XAFS data were measured with fluorescence mode using the Ar-filled Lytle detector.

Operando SR-FTIR Measurements

Operando SR-FTIR measurements were conducted at the infrared spectroscopy and microspectroscopy station (BL01B) of National Synchrotron Radiation Laboratory (NSRL) 58. The CHI 660E electrochemical workstation (Shanghai Chenhua, China) was used to apply voltage to a self-made infrared reflection cell. The infrared spectrums were collected using Bruker Vertex 70 V/s FTIR spectrometer with nitrogen cooled mercury cadmium telluride detector, and the synchrotron radiation infrared beam was focused on the reflection cell using Bruker Hyperion 3000 microscope equipped with a ×15 objective. In the measurements, the gap between the working electrode and the ZnSe window was carefully maintained on the order of microns to prevent excessive water absorption. All spectrums were collected using single-potential alteration FTIR spectroscopy and were acquired by averaging 128 times scan with a 4 cm–1 resolution, and the background spectrums was conducted under open-circuit voltage, the voltage ranges for conducting measurements were 0 V to –1.2 V with an interval of 0.1 V.

Quasi-in situ XPS and AES

Quasi-in situ X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy was conducted of catalysts drop-casted on carbon paper as same as mentioned in Electrodes section. Before test the electrolytes should be CO2-saturated to remove the dissolved oxygen in the solution. Samples were conditioned at different potential for 30 min as one conditioning step. After that the samples was moved to the XPS vacuum chamber without extra exposed to the air. That would avoid the air to influence the catalysts to keep the authentic state under the CO2RR process. XPS (ESCALAB 250X) was measured at Analytical Instrumentation Center, Shanghai Tech University. It was used to characterize the chemical bonding character of the obtained catalysts using a monochromatic of 1486.6 eV (Al Kα source). All XPS spectra were corrected by C 1s peak with the binding energy at 284.6 eV. All of the reagents were used without further purification.

Freeze-quench XAS

The Cu/N0.14C was electrodeposited on a carbon paper electrode, which was an integral part of the XAS sample holder. The Cu/N0.14C was equilibrated potentiostatically for 20 min at −1.1 V vs. RHE. The Cu/N0.14C electrode was rapidly frozen by immersion in liquid nitrogen. The chemical reaction is extremely slow at low temperature environment and the chemical state of the catalyst was well preserved for XAFS data collection periods. X-ray absorption spectra at the Cu K-edge were collected at beamline BL14W1 of the SSRF using a Lytle detector with the Ni filter. The measurements were performed at 18 K using a cryostat (ARS). The excitation energies (scan range 8779–9779 eV) were selected by a Si (111) double-crystal monochromator.

Computational methods

DFT calculations were performed within the frame of plane-wave-based density functional theory (DFT) by VASP package. The generalized gradient approximation (GGA) in the Perdew−Burke−Ernzerhof (PBE) formalism was adopted to treat the electron exchange and correlation energy. The cut-off energy was set to be 500 eV. For structural optimization, 3 × 3 × 2 k-points meshes with a the original Monkhorst-Pack scheme was used and the convergence of energy and force were 10−6 eV and 0.01 eV Å−1, respectively. 6 × 6 × 4 k-points meshes were used for static calculations. A 20 Å vacuum layer in the z-axis direction was added to avoid the interfere of the layer image coupling caused by the periodic boundary conditions59. For more details, please see Supplementary Figs. 20, 28, 29, 31 and Supplementary Data file 1–13.