Abstract

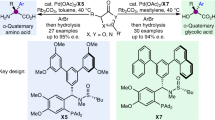

Amines are a class of compounds of essential importance in organic synthesis, pharmaceuticals and agrochemicals. Due to the importance of chirality in many practical applications of amines, enantioselective syntheses of amines are of high current interest. Here, we wish to report the development of (R,Ra)-N-Nap-Pyrinap and (R,Sa)-N-Nap-Pyrinap ligands working with CuBr to catalyze the enantioselective A3-coupling of terminal alkynes, aldehydes, and amines affording optically active propargylic amines, which are platform molecules for the effective derivatization to different chiral amines. With a catalyst loading as low as 0.1 mol% even in gram scale reactions, this protocol is applied to the late stage modification of some drug molecules with highly sensitive functionalities and the asymmetric synthesis of the tubulin polymerization inhibitor (S)-(-)-N-acetylcolchinol in four steps. Mechanistic studies reveal that, unlike reported catalysts, a monomeric copper(I) complex bearing a single chiral ligand is involved in the enantioselectivity-determining step.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chiral amines have been not only used as resolving reagents, chiral ligands, and versatile building blocks in organic synthesis but also demonstrated wide applications in pharmaceuticals and agrochemicals (Fig. 1a)1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9. Thus, the development of highly efficient and enantioselective methods for syntheses of amines is of fundamental interest10,11. Due to the presence of a synthetically versatile carbon–carbon triple bond, propargylic amines are a very important class of compounds commonly used as precursors for other amines and diversified organic motifs. Consequently, attention has been paid to the synthesis of this type of compounds12,13,14. Enantioselective three-component coupling reaction of terminal alkynes, aldehydes, and amines provides one of the most straightforward approaches to propargylic amines due to the easy availability and diversity of the three starting materials. Chiral ligands listed in Fig. 1b have been developed or applied for this reaction by Brown15, Knochel16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23, Carreira24,25, Aponick26,27,28, Naeimi29, Seidel30, and Guiry31,32. However, challenges still remain: (1) Lack of a powerful catalytic system that could be applied to broad spectrum of very challenging combinations for three types of substrates of terminal alkynes, aldehydes, and amines. (2) More practical and efficient catalytic systems are highly desirable. Develo** ligands should be the solution.

It is well known that for atropisomeric diphosphine ligands the backbone skeletons greatly affect their catalytic performance in terms of both reactivity and enantioselectivity. For example, when binaphthyl ligand BINAP (2,2′-bis(diphenylphosphino)-1,1′-binaphthyl) was replaced with the phenyl-naphthyl ligands (MeO-NAPhePHOS and TriMe-NAPhePHOS) and biphenyl ligands (MeO-BIPHEP, SEGPHOS, and Garphos), some of the challenges in enantioselective hydrogenation reactions have been properly addressed33,34,35,36,37,38,39.

In this work, inspired by such backbone effect on catalytic activity and previous studies on axially chiral P,N ligands24,40, we report the development of the ligands phenyl-naphthyl-type ligand N-Ph-Pyrinap L1, N-Nap-Pyrinap L2, and the diphenyl-type ligand L3 to address the challenges with respect to the scope of the combination of alkynes, aldehydes, and amines (Fig. 1d)

Results

Synthesis of Pyrinap ligands

At first, we tried to synthesize Pyriphen L3. But the transformation from triflate S1 to L3 could not be realized by the Ni-catalyzed phosphorylation reaction. The reaction gave only a complex mixture (see Supplementary information for the details). Subsequently, we turned our attention to synthesize N-Ph-Pyrinap L1 or N-Nap-Pyrinap L2. The synthesis of Pyrinap was successfully realized as shown in Fig. 2b: the Suzuki coupling reaction of 3,6-dichloro-4,5-dimethylpyridazine S2 with boronate S3 produced biaryl compound S4 in 58% yield. Subsequent amination reaction with (R)-1-phenylethyl amine or (R)-1-(1-naphthyl)ethyl amine, deprotection, and triflation afforded corresponding triflates S6 or S8, respectively. Finally, Ni-catalyzed coupling of S6 or S8 with HPPh2 provided a mixture of diastereomers of L1 or L2, respectively, which may be separated easily via column chromatography separation on silica gel. The absolute configurations of (R,Sa)-L1 and (R,Sa)-L2 were firmly established by X-ray single-crystal analysis, respectively. (S,Ra)-L2 and (S,Sa)-L2 could also be easily prepared by the same synthetic procedure with (S)-1-(1-naphthyl)ethyl amine (see the Supplementary Fig. 3 for the details). In order to understand the nature of these ligands, we first determined the rotational barrier between (R,Sa)-L2 and (R,Ra)-L2 in toluene at 100 °C to be 30.8 kcal/mol, which is higher than those for O-PINAP (27.6 kcal/mol)41, at 75 °C for Stackphos (28.4 kcal/mol)26, at 50 °C for StackPhim (26.8 and 27.5 kcal/mol)28, and at 80 °C for UCD-PHIM (26.8 kcal/mol)31 (Fig. 2b). Thus, the ligand L2 is configurationally more stable under ambient conditions.

Reagents and conditions: (i) Pd(OAc)2 (5 mol%), PPh3 (20 mol%), Na2CO3 (2 equiv), DME/H2O = 3:1, reflux, (58%); (ii) (R)-1-phenylethyl amine or (R)-1-(1-naphthyl)ethyl amine (1.3 equiv), Pd(OAc)2 (5 mol%), rac-Binap (7.5 mol%), Cs2CO3 (1.4 equiv), toluene, reflux; (iii) HCl (3 M in MeOH/H2O), r.t.; (iv) PhNTf2 (1.0 equiv), Et3N (1.0 equiv), DMAP (10 mol%), DCM, r.t. (for Ar = Ph, 83% yield in step (ii) and 90% yield over 2 steps (iii and iv); for Ar = 1-naphthyl, 86% yield over 2 steps (ii and iii) and 90% yield in step (iv).) (v) NiCl2(dppe) (10 mol%), HPPh2 (2 equiv), DABCO (4 equiv), DMF, 120 °C, 12 h. DME 1,2-dimethoxyethane, DMAP 4-dimethylaminopyridine, DCM dichloromethane, DABCO triethylenediamine, DMF N,N-dimethylformamide.

Optimization of reaction conditions

With these two ligands in hand, we tried the enantioselective A3-coupling of the most challenging propargyl alcohol 1a with a much smaller steric hindrance, benzaldehyde 2a, and pyrrolidine 3a. After some screenings, it was observed that (R,Ra)-L2 ligand gave the highest yield (84%) and enantiomeric excess (ee) (85%) at room temperature (r.t.) (Table 1, entries 1–3). The reaction at 0 °C afforded the product in 90% ee (Table 1, entry 4). When 1.2 equivalent (equiv) each of 2a and 3a were applied, the yield was improved (Table 1, entry 5). The catalyst loading could be reduced to 2.5 mol% with the same level of enantioselectivity (Table 1, entry 6). Following the same conditions reported in ref. 32 (Table 1, entry 7), (S,S,Ra)-UCD-PHIM provided the product in 86% yield with −85% ee (Table 1, entry 8).

Substrate scope

With the optimized reaction conditions in hand, we firstly tested the reactivity and enantioselectivity of various aromatic aldehydes22,25: in general, decent yields and over 90% ee were obtained regardless of the electronic properties of the phenyl groups and the position of substituents (Fig. 3a). A wide range of synthetically useful functional groups, such as halogen (2b, 2j, 2k, 2l), alkoxy (2d, 2e), cyano (2g), ester (2h), trifluoromethyl group (2i), and chiral allene (2m) were intact under the optimal reaction conditions (products (S)-4aba, (R)-4aja, (S)-4aka, (S)-4ala, (S)-4ada, (S)-4aea, (S)-4aga, (S)-4aha, (S)-4aia, and (S,Ra)-4ama). Heteroaromatic aldehydes such as Ts-protected indolecarbaldehyde (2n), 2-benzo[b]thiophenecarbaldehyde (2o), and 2-thiophenecarboxaldehyde (2p) all delivered the corresponding propargylic amines (R)-4ana, (R)-4aoa, and (R)-4apa with good yields and high ee. In addition, aliphatic aldehydes also reacted efficiently to afford the desired products (S)-4aqa and (S)-4ara in high ee.

a Aldehydes scope, b alkynes scope, c amines scope, and d biologically active molecules. Reaction conditions: athe reaction was carried out using 1a (1.2 equiv), 2m (0.15 mmol), and 3a (1.2 equiv). bThe reaction was carried out using 1a (6.25 mmol), 2o (1.05 equiv), 3a (1.05 equiv), CuBr (0.1 mol%), (R,Ra)-L2 (0.11 mol%), and 4 Å MS (1.9 g) in toluene (16 mL) at 0 °C for 4 d. cThe reaction was carried out using 1a (12.5 mmol), 2p (1.05 equiv), 3a (1.05 equiv), CuBr (0.1 mol%), (R,Ra)-L2 (0.11 mol%), and 4 Å MS (1.9 g) in toluene (31 mL) at 0 °C for 2 days. dThe reaction was carried out using 1d (1.2 equiv), 2a (0.5 mmol), and 3b (1.2 equiv). eThe reaction was carried out using 1d (0.5 mmol), 2t (2 equiv), 3e·HCl (1.2 equiv), NEt3 (2.2 equiv), CuBr (2.5 mol%), (R,Ra)-L2 (2.75 mol%), and 4 Å MS (150.3 mg) in DCM (1.25 mL) at 0 °C for 24 h. fDMC (1.25 mL) was used as solvent. gThe reaction was carried out using trimethylsilylacetylene 1l (1.5 equiv), 3-phenylpropiolaldehyde 2w (0.5 mmol), 3i (1.0 equiv), CuBr (2.5 mol%), (R,Ra)-L2 (2.75 mol%), and 4 Å MS (150.6 mg) in DCM (1.25 mL) at 0 °C for 2.5 days. hThe reaction was carried out on a 0.25 mmol scale. iThe reaction was carried out using 1 (0.5 mmol), 2 (1.2 equiv), 3·HCl (1.2 equiv), and NEt3 (2.2 equiv) in DMC (1.25 mL). jThe reaction was carried out using 1 (0.5 mmol), 2 (1.2 equiv), 3·HCl (1.2 equiv), and NEt3 (2.2 equiv) in DCM (1.25 mL). The absolute configuration before the compound no. refers to the newly generated propargylic chiral center.

The scope of terminal alkynes42 was subsequently examined (Fig. 3b): non-sterically hindered homopropargyl alcohol 1b could produce (S)-4bsa in 96% yield with 90% ee. Even the reaction of 1°-alkyl-substituted terminal alkyne 1c without the hydroxyl group afforded the corresponding propargylic amine (S)-4caa in 90% ee at −5 °C. As for aryl-substituted alkyne 1d, high enantioselectivity was also obtained for the product (S)-4daa30. As expected, excellent yields and ee for products (S)-4eaa and (S)-4eqa were observed for tertiary propargylic alcohol 1e with aromatic aldehyde 2a or aliphatic aldehyde 2q.

Encouraged by the above results, we turned to explore the scope of amines (Fig. 3c)30: a range of amines with different types of aldehydes and alkynes were tested (Fig. 3c). The ring size of 6- to 8-membered cyclic amines had no obvious effect on the enantiocontrol of the reaction (products (S)-4fab, (S)-4dab, (S)-4aqb, (S)-4gac, and (S)-4had). For 4-piperidone 3e, which was used as an ammonia equivalent25, chiral (S)-4dte was obtained in 76% yield and 90% ee under a further modified conditions. Morpholine 3f could also furnish the product (S)-4iaf in 85% yield with 94% ee by using dimethyl carbonate instead of toluene as the solvent. Meanwhile, the reaction could be extended to acyclic amines with good yields and excellent ee for products (S)-4jag and (S)-4kah. As we know that dibenzyl amine 3i is an important amine due to the potential of debenzylation for further possible functionalization of the nitrogen atom. It should be noted that the known ligands for the reactions with dibenzyl amine 3i afforded (S)-4eai and (S,E)-4lvi in 49% yield with an ee of merely 32% and 96% yield with 82% ee, respectively22,32. Thus, the scope of this transformation with dibenzyl amine 3i was investigated: both aromatic and aliphatic aldehydes could achieve excellent yields and ee with tertiary propargylic alcohol 1e (products (S)-4eai and (S)-4eui). Even an alk-2-enal or 2-alkynal, which may readily undergo conjugate addition with the amine, worked with an excellent selectivity: cinnamaldehyde E-2v smoothly yielded the corresponding product (S,E)-4lvi in 80% yield and 99% ee; the reaction of 3-phenylpropiolaldehyde 2w under standard conditions was very sluggish in toluene, producing (S)-4lwi in merely 6% nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) yield. However, 88% yield and 94% ee of (S)-4lwi could be obtained by using dichloromethane (DCM) as solvent with 1.5 equiv of trimethylsilylacetylene 1l27. Importantly, all four different stereoisomers of 4oti may be obtained in excellent yields, ee, and diastereomeric excess (d.e.) by starting from optically active propargylic alcohol (R)-1o43 or (S)-1o43 and chiral ligand (R,Ra)-L2 or (R,Sa)-L2, respectively.

Having illustrated the broad substrate scope and efficient enantiocontrol ability of this catalytic system, late-stage modification of biologically active or drug molecules were further performed (Fig. 3d): alkynes derivatives of carbohydrate d-fructose 1p and amino acid l-phenylalanine (S)-1q44 provided the corresponding products (R)-4poa and (S,S)-4qaa smoothly in high yields and d.e.; the terminal alkyne groups in commercial drugs, ethisterone 1r, mestranol 1s, and Boc-protected Rasagiline (R)-1t45, may be readily converted to corresponding chiral propargylic amines (S)-4raa, (S)-4saa, (S)-4sxa, and (S,R)-4tba, without affecting other functionalities. For ethisterone 1r, cases of match and mismatch between the substrate chirality and the ligand chirality were observed: the reaction with (R,Ra)-L2 or (S,Ra)-L2 yielded (S)-4raa in 93% yield with 97% d.e. or 82% yield with 98% d.e., respectively. As a comparison, with (R,Sa)-L2 or (S,Sa)-L2, the same product was produced in 50% yield with 75% d.e. or 83% yield with 67% d.e., respectively. The reaction of the terminal alkyne derivative of dihydroartemisinin, indole carboaldehyde, and piperidine afforded (R)-4unb and (S)-4unb successfully via the current protocol: even the fragile bridged peroxide group in the dihydroartemisinin, which plays an important role in antimalarial activity46, was tolerated. In this case, the absolute configuration of the newly formed propargylic chiral center was completely controlled by the axial chirality of the chiral ligand, regardless of the substrate chirality or the central chirality of the chiral ligand. This may be explained by the fact that the chirality in dihydroartemisinin is far away from the terminal sp carbon atom. Moreover, amine-containing drug molecules, trimetazine (3j), duloretine ((S)-3k), and paroxetine ((S,R)-3l), could be used directly in this reaction to deliver products (S)-4daj, (S,S)-4dak, and (S,S,R)-4dal in high enantioselectivity under slightly modified conditions (Fig. 3d).

To demonstrate the practical utility, the reaction of simple propargyl alcohol 1a, cyclohexanecarbaldehyde 2q, and pyrrolidine 3a was performed on 12.5 mmol scale with only 0.1 mol% of CuBr and 0.11 mol% of (R,Ra)-L2 affording chiral propargylic amine (S)-4aqa42 in 78% yield (2.17g) and 91% ee after a simply acid–base extraction. Heteroaromatic aldehyde 2o could also produce 1.12 g of (R)-4aoa in 66% yield and 93% ee on 6.25 mmol scale with 0.1 mol% of catalyst (Fig. 3a).

Synthetic applications

The colchicine degradation product (S)-(−)-N-acetylcolchinol (S)-6 is the tubulin polymerization inhibitor47,48,49. Previously reported enantioselective synthesis of (S)-6 suffered from using stoichiometric amounts of chiral reagents and step-economy9,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58. We reasoned that our methodology could be applied to the highly efficient enantioselective synthesis of (S)-6 as outlined in Fig. 4a. The key step would be the enantioselective A3 reaction with the above-mentioned challenging dibenzyl amine 3i (Fig. 4b): at first, the enantioselective A3-coupling reaction of alkyne 1v, aromatic aldehyde 2y, and dibenzyl amine 3i under standard conditions at r.t. was very sluggish, affording the desired propargylic amine (R)-4vyi in 81% yield and 96% ee with 19% of 1v being recovered even after 7 days. Fortunately, this targeted transformation could be efficiently achieved at r.t. with 1.0 mol% of CuBr and 1.1 mol% of (R,Sa)-L2 in dimethyl carbonate producing (R)-4vyi in 98% yields and 95% ee within 48 h. Followed by Pd/C-catalyzed hydrogenation/debenzylation and acetylation, the key intermediate (S)-5 was furnished in 81% yield and 94% ee. Finally, after intramolecular oxidative coupling of (S)-5, (S)-(-)-N-acetylcolchinol (S)-6 was obtained in 50% yield and 95% ee (47% yield and 97% ee after recrystallization from MeOH/H2O; \([\alpha ]_{\mathrm{D}}^{27} = - 37.5\) (c = 0.99, CHCl3), reported value: 94% ee, \([\alpha ]_{\mathrm{D}}^{27} = - 34.0\) (c = 1, CHCl3)56; \([\alpha ]_{\mathrm{D}}^{20} = - 55.8\) (c = 0.135, CHCl3)57.

a Retrosynthetic analysis of (S)-6. b A catalytic enantioselective synthesis of (S)-(-)-N-acetylcolchinol (S)-6. c Transformation of propargylic amines (S)-4aaa and (S)-4aqa. Reagents and conditions: (i) Ni(OAc)2·4H2O (1 equiv), NaBH4 (1 equiv), ethylenediamine (3.5 equiv), EtOH, H2 (1 atm), r.t., 3 h; (ii) LiAlH4 (2 equiv), THF, 0 °C to r.t., 3 h; (iii) TBSCl (1.2 equiv), imidazole (2 equiv), DCM, r.t., 12 h; (iv) ZnI2 (50 mol%), toluene, 110 °C, 8 h; (v) TBAF·3H2O (1 equiv), THF, 0 °C to r.t., 12 h; (vi) phthalimide (1 equiv), DEAD (1.1 equiv), PPh3 (1 equiv), THF, 0 °C to r.t., 12 h. DCM dichloromethane, DEAD diethyl azodicarboxylate, DMAP 4-dimethylaminopyridine, DMC dimethyl carbonate, TBAF tetrabutylammonium fluoride, TBSCl tert-butyldimethylsilyl chloride, TFA trifluoroacetic acid, TFAA trifluoroacetic anhydride, THF tetrahydrofuran.

As stated in the introduction, the unique structure of chiral propargylic amine offers opportunities for further synthetic elaboration for the asymmetric syntheses of different amines (Fig. 4c): partial reduction of the C≡C triple bond in (S)-4aaa using “P-2 nickel” in the presence of ethylenediamine or LiAlH4 provided highly selectively (R,Z)-7 and (R,E)-7 in excellent yields and ee59,60; the Mitsunobu reaction61 of (S)-4aaa with phthalimide afforded 1,4-butynyl diamine (S)-8 in 74% yield and 91% ee; primary α-allenols (R)-9 may also be prepared with 75% yield and 94% ee by TBS protection, ZnI2-mediated allenation reaction, and deprotection62,63.

Mechanistic studies

It has been reported that Quinap demonstrated a strong positive nonlinear effect16, while a weak positive nonlinear effect was observed for StackPhos (see the Supplementary information file of ref. 27). Interestingly, a perfect linear effect was observed between the enantiopurity of (R,Ra)-L2 and product (S)-4aqa for the current reaction shown in Fig. 5a, which indicated that the catalytically active species most likely involves a monomeric copper(I) complex bearing a single chiral ligand. In order to acquire more information of the catalyst species in this reaction, we tried to isolate the Cu(I)-(R,Ra)-L2 complex64, but failed. We then performed 31P-NMR experiment to probe the coordination of CuBr with (R,Ra)-L2 in d6-toluene. A broad resonance at δ = −4.7 p.p.m. was observed in the 31P-NMR spectrum of the resulting mixture, while the resonance at δ = −12.7 p.p.m. corresponding to the free ligand (R,Ra)-L2 disappeared (for the details on 31P-NMR experiment, see Supplementary Figs. 5 and 6). The reported 31P-NMR chemical shifts for 1,3-bis(diphenylphosphanyl)propane (dppp) and [Cu(dppp)2]BF4 are δ = −17.2 p.p.m. and δ = −8.5 p.p.m., respectively65. The change in 31P-NMR chemical shift suggested that the P atom should coordinate to the Cu(I) atom in the solution, but may not be as strong as in the reported case. Moreover, DFT calculations were carried out to investigate the stability of two coordination modes: N,P-coordinated intermediate Int_N,P and N-coordinated intermediate Int_N (Fig. 5c, see Supplementary information, pp 87–92 for the detailed information of computational methods). The calculated results showed that Int_N,P was more stable than Int_N by 1.5 kcal/mol.

a The linear effect. b DFT calculations on the stability of two coordination modes. The calculations were performed at the M06/SDD-6-311++G(2d,p)/SMD(toluene)//M06/LANL2DZ-6-31G(d,p) level of theory at 273.15 K. The free energies ΔG are given with respect of Int_N,P. Bond lengths are given in angstroms. c SAESI-MS studies. (i) Expanded SAESI-MS spectrum showing the signal from m/z 540–760. (ii) SAESI-MS/MS spectrum showing the signal of MS-Int. II at m/z 752. (iii) SAESI-MS/MS spectrum showing the signal of MS-Int. V at m/z 929. (iv) SAESI-MS/MS spectrum showing the signal of MS-Int. VI at m/z 991.

Solvent-assisted electrospray ionization mass spectrometric experiment (SAESI-MS) was further applied to unveil the nature of catalytically active species in this reaction66. First, a solution of CuBr (6.25 μmol), (R,Ra)-L2 (6.88 μmol), and alkyne 1d (0.25 mmol) in toluene (1 mL) was stirred at r.t. under Ar atmosphere. After 10 min, a signal with m/z of 650, which matched the m/z of mono-ligated species [Cu((R,Ra)-L2)]+ (MS-Int. I, Fig. 5c(i), calcd for C40H3463CuN3P+: 650.2) was observed. Meanwhile, an alkyne-coordinated intermediate MS-Int. II was confirmed by a SAESI-MS/MS experiment (Fig. 5c(ii)). Then, aldehyde 2a (0.3 mmol) and pyrroline 3a (0.3 mmol) were added. The signal m/z of 928.7 and 990.7 were attributed to mono-ligated intermediates MS-Int. V (Fig. 5c(iii), calcd for C59H5563CuN4OP+: 929.3) and MS-Int. VI (Fig. 5c(iv), calcd for C59H5479Br63CuN4P+: 991.3), respectively. Their identities were further confirmed by the SAESI-MS/MS experiment (for details on MS study, see Supplementary Figs. 7–14).

Based on these experimental data, we proposed a mechanism shown in Fig. 6: the mono-ligated Int. I would interact with the terminal alkyne 1d to generate Int. II, in which the chiral amine in the ligand may act as a proton shuttle. The reaction of amine with aldehyde generated Int. III, which would coordinate with the Cu atom in Int. II to form Int. IV. H+-mediated elimination of water formed the iminium species in Int. V. Enantioselective 1,2-addition would afford Int. VI (Re face attack is more favored), which underwent disassociation to release the product-propargylic amine (S)-4daa and regenerate the catalytically active Int. I to finish the catalytic cycle.

In conclusion, we have developed axially chiral P,N-ligands Pyrinap for the highly efficient catalytic enantioselective A3-coupling reaction of readily available alkynes, aldehydes, and amines to provide a variety of chiral amine-synthesis platform molecules, chiral propargylic amines, in high yields and enantioselectivity. Compared to known ligands, the salient features of this work are: (a) a general catalytic system that could be applied to a variety of challenging substrate combinations with high enantioselectivity; (b) monomeric copper(I) complex bearing a single chiral ligand has been identified as the catalytically active species; (c) the reaction has been successfully applied to the late-stage modification of some drug molecules with the sensitive functionalities survived; (d) synthetic potential has further been demonstrated by enantioselective synthesis of (S)-(-)-N-acetylcolchinol in four steps. Further studies on applications of Pyrinap and the development of diphenyl-type ligand Pyriphen L3 are being actively pursued in this laboratory.

Methods

General procedure for the catalytic enantioselective A3-coupling reaction

To a flame-dried Schlenk tube were added CuBr (1.8 mg, 0.0125 mmol), (R,Ra)-L2 (8.1 mg, 0.01375 mmol), 4 Å molecular sieves (150.5 mg), and toluene (0.75 mL) sequentially under Ar atmosphere. After being stirred at room temperature for 30 min, 1a (28.0 mg, 0.5 mmol) and 2a (63.7 mg, 0.6 mmol)/toluene (0.5 mL) were added sequentially under Ar atmosphere. The resulting mixture was stirred at 0 °C for another 10 min, followed by the addition of pyrrolidine 3a (42.7 mg, 0.6 mmol). After being stirred at 0 °C for 24 h, the reaction was complete as monitored by thin layer chromatography. The resulting mixture was filtrated through a short pad of basic aluminum oxide (200–300 mesh) eluted with dichloromethane/MeOH (10:1, 44 mL). After evaporation, the residue was purified by chromatography on silica gel (eluent: petroleum ether/ethyl acetate = 2:1) to afford (S)-4aaa (74.9 mg, 70%) as a liquid: 90% ee (high-performance liquid chromatography conditions: Chiralcel OD-H column, hexane/i-PrOH = 95/5, 1.2 mL/min, λ = 214 nm, tR(major) = 10.1 min, tR(minor) = 7.7 min); \([\alpha ]_{\mathrm{D}}^{31} = - 28.1\) (c = 1.05, CHCl3); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.51 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H, ArH), 7.33 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H, ArH), 7.27 (t, J = 6.4 Hz, 1H, ArH), 4.62 (s, 1H, CH), 4.36 (d, J = 1.6 Hz, 2H, OCH2), 2.67–2.51 (m, 4H, 2 × NCH2), 2.04 (s, 1 H, OH), 1.83–1.71 (m, 4H, 2 × CH2); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 138.9, 128.24, 128.21, 127.7, 85.0, 82.7, 58.9, 50.9, 50.5, 23.2; MS (EI) m/z (%) 215 (M+, 20.49), 138 (100); IR (neat): ν = 3065, 2960, 2924, 2871, 2841, 2729, 1489, 1455, 1372, 1345, 1309, 1270, 1233, 1206, 1121, 1087, 1074, 1033, 1024 cm−1; HRMS calcd for C14H18NO ([M + H]+): 216.1383, found: 216.1381.

Data availability

All data that support the findings of this study are available in the online version of this paper in the accompanying Supplementary information (including experimental procedures, compound characterization data, and spectra).

The X-ray crystallographic coordinates for structures of (R,Sa)-N-Ph-Pyrinap and (R,Sa)-N-Nap-Pyrinap reported in this Article have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC) under deposition numbers CCDC 1911487 ((R,Sa)-N-Ph-Pyrinap) and 1911488 ((R,Sa)-N-Nap-Pyrinap). These data can be obtained free of charge from http://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.

References

Reynolds, T. Hemlock alkaloids from socrates to poison aloes. Phytochemistry 66, 1399–1406 (2005).

Rodgman, A. & Perfetti, T. A. The Chemical Components of Tobacco and Tobacco Smoke 2nd edn (CRC Press, 2013).

Zhang, Q., Tu, G., Zhao, Y. & Cheng, T. Novel bioactive isoquinoline alkaloids from Carduus crispus. Tetrahedron 58, 6795–6798 (2002).

Blaser, H.-U. The chiral switch of (S)-metolachlor: a personal account of an industrial odyssey in asymmetric catalysis. Adv. Synth. Catal. 344, 17–31 (2002).

Hirota, Y., Sugiura, H., Kuroda, N., Wada, T. & Tsujimoto, K. Imidazole derivatives, bactericides containing them, and process for their preparation. Patent EP0248086B1 (1985).

Oldfield, V., Keating, G. M. & Perry, C. M. Rasagiline. Drugs 67, 1725–1747 (2007).

Corbett, J. W. et al. Expanded-spectrum nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors inhibit clinically relevant mutant variants of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43, 2893–2897 (1999).

Aladesanmi, A. J., Kelley, C. J. & Leary, J. D. The constituents of dysoxylum lenticellare. I. Phenylethylisoquinoline, homoerythrina, and dibenzazecine alkaloids. J. Nat. Prod. 46, 127–131 (1983).

Sitnikov, N. S. & Fedorov, A. Y. Synthesis of allocolchicinoids: a 50 year journey. Russ. Chem. Rev. 82, 393–411 (2013).

Nugent, T. C. Chiral Amine Synthesis: Methods, Developments and Applications (Wiley, Weinheim, 2010).

Li, W. & Zhang, X. Stereoselective Formation of Amines (Springer, Heidelberg, 2014).

Lauder, K., Toscani, A., Scalacci, N. & Castagnolo, D. Synthesis and reactivity of propargylamines in organic chemistry. Chem. Rev. 117, 14091–14200 (2017).

Peshkov, V. A., Pereshivko, O. P. & Van der Eycken, E. V. A walk around the A3-coupling. Chem. Soc. Rev. 41, 3790–3807 (2012).

Rokade, B. V., Barker, J. & Guiry, P. J. Development of and recent advances in asymmetric A3 coupling. Chem. Soc. Rev. 48, 4766–4790 (2019).

Alcock, N. W., Brown, J. M. & Hulmes, D. I. Synthesis and resolution of 1-(2-diphenylphosphino-1-naphthyl)isoquinoline; a P-N chelating ligand for asymmetric catalysis. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 4, 743–756 (1993).

Gommermann, N., Koradin, C., Polborn, K. & Knochel, P. Enantioselective, copper(I)-catalyzed three-component reaction for the preparation of propargylamines. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 42, 5763–5766 (2003).

Dube, H., Gommermann, N. & Knochel, P. Synthesis of chiral α-aminoalkylpyrimidines using an enantioselective three-component reaction. Synthesis 2015–2025 (2004).

Gommermann, N. & Knochel, P. Practical highly enantioselective synthesis of terminal propargylamines. An expeditious synthesis of (S)-(+)-coniine. Chem. Commun. 2324–2325 (2004).

Gommermann, N. & Knochel, P. 2-Phenallyl as a versatile protecting group for the asymmetric one-pot three-component synthesis of propargylamines. Chem. Commun. 4175–4177 (2005).

Gommermann, N. & Knochel, P. Highly enantioselective synthesis of propargylamines using (mesitylmethyl)benzylamine. Synlett 2005, 2799–2801 (2005).

Gommermann, N. & Knochel, P. Preparation of functionalized primary chiral amines and amides via an enantioselective three-component synthesis of propargylamines. Tetrahedron 61, 11418–11426 (2005).

Gommermann, N. & Knochel, P. Practical highly enantioselective synthesis of propargylamines through a copper-catalyzed one-pot three-component condensation reaction. Chem. Eur. J. 12, 4380–4392 (2006).

Gommermann, N. & Knochel, P. N,N-dibenzyl-N-[1-cyclohexyl-3-(trimethylsilyl)-2-propynyl]-amine from cyclohexanecarbaldehyde, trimethylsilylacetylene and dibenzylamine. Org. Synth. 84, 1–10 (2007).

Knöpfel, T. F., Aschwanden, P., Ichikawa, T., Watanabe, T. & Carreira, E. M. Readily available biaryl P,N ligands for asymmetric catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 43, 5971–5973 (2004).

Aschwanden, P., Stephenson, C. R. J. & Carreira, E. M. Highly enantioselective access to primary propargylamines: 4-piperidinone as a convenient protecting group. Org. Lett. 8, 2437–2440 (2006).

Cardoso, F. S. P., Abboud, K. A. & Aponick, A. Design, preparation, and implementation of an imidazole-based chiral biaryl P,N-ligand for asymmetric catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 14548–14551 (2013).

Paioti, P. H. S., Abboud, K. A. & Aponick, A. Catalytic enantioselective synthesis of amino skipped diynes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 2150–2153 (2016).

Paioti, P. H. S., Abboud, K. A. & Aponick, A. Incorporation of axial chirality into phosphino-imidazoline ligands for enantioselective catalysis. ACS Catal. 7, 2133–2138 (2017).

Naeimi, H. & Moradian, M. Thioether-based copper(I) schiff base complex as a catalyst for a direct and asymmetric A3-coupling reaction. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 25, 429–434 (2014).

Zhao, C. & Seidel, D. Diastereofacial π-stacking as an approach to access an axially chiral P,N-ligand for asymmetric catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 4650–4653 (2015).

Rokade, B. V. & Guiry, P. J. Diastereofacial π-stacking as an approach to access an axially chiral P,N-ligand for asymmetric catalysis. ACS Catal. 7, 2334–2338 (2017).

Rokade, B. V. & Guiry, P. J. Enantioselective catalytic asymmetric A3 coupling with phosphino-imidazoline ligands. J. Org. Chem. 84, 5763–5772 (2019).

Miyashita, A. et al. Synthesis of 2,2′-bis(diphenylphosphino)-1,1′-binaphthyl (BINAP), an atropisomeric chiral bis(triaryl)phosphine, and its use in the rhodium(I)-catalyzed asymmetric hydrogenation of α-(acylamino)acrylic acids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 102, 7932–7934 (1980).

Schmid, R., Foricher, J., Cereghetti, M. & Schönholzer, P. Axially dissymmetric diphosphines in the biphenyl series: synthesis of (6,6′-dimethoxybiphenyl-2,2′-diyl)bis(diphenylphosphine)(‘Meo-BIPHEP’) and analogues via an ortho-lithiation/iodination Ullmann-reaction approach. Helv. Chim. Acta 74, 370–389 (1991).

Genêt, J. P. et al. Enantioselective hydrogenation reactions with a full set of preformed and prepared in situ chiral diphosphine-ruthenium (II) catalysts. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 5, 675–690 (1994).

Saito, T. et al. New chiral diphosphine ligands designed to have a narrow dihedral angle in the biaryl backbone. Adv. Synth. Catal. 343, 264–267 (2001).

Michaud, G., Bulliard, M., Ricard, L., Genêt, J.-P. & Marinetti, A. A strategy for the stereoselective synthesis of unsymmetric atropisomeric ligands: preparation of NAPhePHOS, a new biaryl diphosphine. Chem. Eur. J. 8, 3327–3330 (2002).

Madec, J., Michaud, G., Genêt, J.-P. & Marinetti, A. New developments in the synthesis of heterotopic atropisomeric diphosphines via diastereoselective aryl coupling reactions. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 15, 2253–2261 (2004).

Abdur-rashid, K. et al. Biaryl diphosphine ligands, intermediates of the same and their use in asymmetric catalysis. Patent WO2012/31358 (2012).

Rokade, B. V. & Guiry, P. J. Axially chiral P,N-ligands: some recent twists and turns. ACS Catal. 8, 624–643 (2017).

Fujimori, S. et al. Stereoselective conjugate addition reactions using in situ metallated terminal alkynes and the development of novel chiral P,N-ligands. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn 80, 1635–1657 (2007).

Fan, W. & Ma, S. An easily removable stereo-dictating group for enantioselective synthesis of propargylic amines. Chem. Commun. 49, 10175–10177 (2013).

Xu, D., Li, Z. & Ma, S. Novozym-435-catalyzed enzymatic separation of racemic propargylic alcohols. A facile route to optically active terminal aryl propargylic alcohols. Tetrahedron Lett. 44, 6343–6346 (2003).

Santandrea, J., Minozzi, C., Cruché, C. & Collins, S. K. Photochemical dual-catalytic synthesis of alkynyl sulfides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 12255–12259 (2017).

Marras, G., Rasparini, M., Tufaro, R., Castaldi, G. & Ghisleri, D. A process for the preparation of (R)-1-aminoindanes. Patent WO2010/49379 (2010).

China Cooperative Research Group on Qinghaosu and Its Derivatives as Antimalarials. Chemical studies on qinghaosu (artemisinine). J. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2, 3–8 (1982).

Davis, P. D. et al. ZD6126: a novel vascular-targeting agent that causes selective destruction of tumor vasculature. Cancer Res. 62, 7247–7253 (2002).

Bergemann, S. et al. Novel B-ring modified allocolchicinoids of the NCME series: Design, synthesis, antimicrotubule activity and cytotoxicity. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 11, 1269–1281 (2003).

Micheletti, G. et al. Vascular-targeting activity of ZD6126, a novel tubulin-binding agent. Cancer Res. 63, 1534–1537 (2003).

Čech, J. & Šantavý, F. The effect of hydrogen peroxide in alkaline medium on colchiceine. Collect. Czech. Chem. Commun. 14, 532–539 (1949).

Fernholz, H. Űber die umlagerung des colchicins mit natriumalkoholat und die struktur des ringes C. Justus Liebigs Ann. Chem. 568, 63–72 (1950).

Sawyer, J. S. & Macdonald, T. L. Total synthesis of (±)-N-acetylcolchinol. Tetrahedron Lett. 29, 4839–4842 (1988).

Besong, G., Jarowicki, K., Kocienski, P. J., Sliwinski, E. & Boyle, F. T. Synthesis of (S)-(-)-N-acetylcolchinol using intramolecular biaryl oxidative coupling. Org. Biomol. Chem. 4, 2193–2207 (2006).

Wu, T. R. & Chong, J. M. Asymmetric synthesis of propargylamides via 3,3′-disubstituted binaphthol-modified alkynylboronates. Org. Lett. 8, 15–18 (2006).

Broady, S. D., Golden, M. D., Leonard, J., Muir, J. C. & Maudet, M. Asymmetric synthesis of (S)-(-)-N-acetylcolchinol via ullmann biaryl coupling. Tetrahedron Lett. 48, 4627–4630 (2007).

Besong, G. et al. A synthesis of (aR,7S)-(-)-N-acetylcolchinol and its conjugate with a cyclic RGD peptide. Tetrahedron 64, 4700–4710 (2008).

Nicolaus, N. et al. A convenient entry to new C-7-modified colchicinoids through azide alkyne [3+2] cycloaddition: application of ring-contractive rearrangements. Heterocycles 82, 1585–1600 (2010).

Shchegravina, E., Svirshchevskaya, E., Schmalz, H.-G. & Fedorov, A. A facile synthetic approach to nonracemic substituted pyrrolo-allocolchicinoids starting from natural colchicine. Synthesis 51, 1611–1622 (2018).

Brown, C. A. & Ahuja, V. K. “P-2 nickel” catalyst with ethylenediamine, a novel system for highly stereospecific reduction of alkynes to cis-olefins. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 553–554 (1973).

Courtois, G. & Miginiac, P. Action d’organométalliques fonctionnels sur les gem-aminoéthers et les sels d’immonium. II. Synthèse d’amines γ-fonctionnelles α-acétyléniques, α-éthyléniques Z ou E et saturées. Bull. Soc. Chim. Fr. 2, 21–27 (1983).

Mitsunobu, O. & Yamada, M. Preparation of esters of carboxylic and phosphoric acid via quaternary phosphonium salts. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn 40, 2380–2382 (1967).

Ye, J., Fan, W. & Ma, S. tert-Butyldimethylsilyl-directed highly enantioselective approach to axially chiral α-allenols. Chem. Eur. J. 19, 716–720 (2013).

Ye, J. & Ma, S. Preparation of (R)-4-cyclohexyl-2,3-butadien-1-ol. Org. Synth. 91, 233–247 (2014).

Koradin, C., Polborn, K. & Knochel, P. Enantioselective synthesis of propargylamines by copper-catalyzed addition of alkynes to enamines. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 41, 2535–2538 (2002).

Comba, P., Katsichtis, C., Nuber, B. & Pritzkow, H. Solid-state and solution structural properties of copper(I) compounds with bidentate phosphane ligands. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 1999, 777–783 (1999).

Zhang, J.-T., Wang, H.-Y., Zhu, W., Cai, T.-T. & Guo, Y.-L. Solvent-assisted electrospray ionization for direct analysis of various compounds (complex) from low/nonpolar solvents and eluents. Anal. Chem. 86, 8937–8942 (2014).

Acknowledgements

Financial support from National Science Foundation of China Program (21690063) is greatly appreciated. We thank Mr. Yuchen Zhang in this group for reproducing the syntheses of (S)-4aia and (S)-4lwi in Fig. 3 presented in the text, and we thank Mr. Wei-Feng Zheng in this group for providing the aldehyde (Ra)-2m.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.M. directed the research and developed the concept of the reaction with Q.L. and H.X., who also performed the experiments and prepared the Supplementary Information. Q.L. and H.X. contributed equally to this work. Y.G. directed the SAESI-MS reaction with Y.L., who also collected and analyzed the SAESI-MS spectra data. X.Z. and Y.Y. performed the computational studies. Q.L., H.X., and S.M. checked the experimental data. Q.L. and S.M. wrote the manuscript with contributions from the other authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Q., Xu, H., Li, Y. et al. Pyrinap ligands for enantioselective syntheses of amines. Nat Commun 12, 19 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-20205-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-20205-0

- Springer Nature Limited

This article is cited by

-

Atomically precise ultrasmall copper cluster for room-temperature highly regioselective dehydrogenative coupling

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Catalytic enantioselective reductive alkynylation of amides enables one-pot syntheses of pyrrolidine, piperidine and indolizidine alkaloids

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Outer delocalized electron aggregation of bromide bridged core—shell CuBr@C for hydrogen evolution reaction

Nano Research (2023)