Abstract

Background

We examined the role of psychological well-being related measures in explaining the associations between obesity and increased risk of non-communicable diseases (NCDs: hypertension, heart disease, stroke, diabetes, arthritis, cancer, and memory-related disease) in older adults.

Methods

Data were from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA), UK (baseline: Wave 4—2008/2009; n = 8127) and the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), US (baseline: Waves 9 and 10—2008/2010; n = 12,477). Objective body mass index was used to define obesity. A range of psychological well-being related measures (e.g., depressive symptoms, life satisfaction) was available in ELSA (n = 7) and HRS (n = 15), and an index of overall psychological well-being was developed separately in each study. NCDs were from a self-reported doctor diagnosis and/or other assessments (e.g., biomarker data) in both studies; and in ELSA, NCDs from linked hospital admissions data were examined. Longitudinal associations between obesity status, psychological well-being measures, and NCDs were examined using Cox proportional hazard models (individual NCDs) and Poisson regression (a cumulative number of NCDs). Mediation by psychological well-being related measures was assessed using causal mediation analysis.

Results

Obesity was consistently associated with an increased prospective risk of hypertension, heart disease, diabetes, arthritis, and a cumulative number of NCDs in both ELSA and HRS. Worse overall psychological well-being (index measure) and some individual psychological well-being related measures were associated with an increased prospective risk of heart disease, stroke, arthritis, memory-related disease, and a cumulative number of NCDs across studies. Findings from mediation analyses showed that neither the index of overall psychological well-being nor any individual psychological well-being related measures explained (mediated) why obesity increased the risk of develo** NCDs in both studies.

Conclusion

Obesity and psychological well-being may independently and additively increase the risk of develo** NCDs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Obesity is now a major health problem in many countries. In England, the prevalence of obesity almost doubled from 15 to 28% between 1993–2019 [1]. The prevalence of obesity in the US is higher at 42% in 2017–2020 which increased from 31% in 1999–2000 [2]. Obesity is associated with an increased risk of numerous non-communicable diseases (NCDs), including cardiovascular diseases, diabetes mellitus, musculoskeletal disorders, and cancer [3], as well as shortened life expectancy by up to 14 years [4]. Due to the reported negative impacts of obesity, understanding the mechanisms which explain why obesity increases risks of NCDs will be key to prevention efforts and reducing the obesity-related NCD burden.

Adverse physical health outcomes of obesity have been traditionally explained by the objective effect of adiposity (i.e., excess fat mass) on a range of physiological processes in the body. Accumulation of visceral adipose tissue (i.e., adipose tissue localised intra-abdominally in visceral compartments) is thought to be responsible for metabolic dysregulations, including inflammation, dyslipidaemia, and insulin resistance [5, 6]. In line with this hypothesis, empirical studies found that obesity is associated with a range of clinical indicators of metabolic (e.g., dyslipidaemia) [7], cardiovascular (e.g., heart rates) [8], and immune system functioning [9], including when these indicators were combined into a ‘physiological dysregulation’ index [10, 11]. Physiological effects of obesity have been shown to increase the risk of develo** disease. For example, dyslipidaemia is associated with an increased risk of heart disease [12], cancer [13], and diabetes [10]. However, the extent to which psychological well-being related measures explain obesity-related NCD risk has not been investigated.

In this present study, we examined the role of a broad range of psychological well-being related measures in explaining the prospective association between obesity and seven NCDs (hypertension, heart disease, stroke, diabetes, arthritis, cancer, and memory-related disease). Consistent with theoretical models which suggest that the psychosocial burden of obesity may contribute to obesity-related disease outcomes, we hypothesised that psychological well-being related measures may explain why obesity is associated with increased NCD risk. We used two large comparable representative longitudinal studies from the UK and the US. We first tested our hypotheses using data from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA), UK and then examined the generalisability of the findings to the US; Health and Retirement Study (HRS).

Methods

The analysis approach for this study was pre-registered at https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/JRQAP.

Study design and data

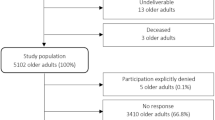

English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA)

ELSA is a representative longitudinal study of English non-institutional older adults (≥50 years). ELSA commenced in 2002 (Wave 1) and follow-up interviews have been conducted every 2 years from 2004–2005 (Wave 2) to 2021–2023 (Wave 10). Physical and biomarker assessments were carried out for all participants every 4 years (Wave 2, 4, 6, 8/9) [35]. For this study, we selected Wave 4 (2008–2009) as a baseline because a large range of psychological well-being related measures was collected in this wave. Follow-up assessments on NCDs ranged from Wave 5 up to the most recent available data (Wave 9) with a maximum follow-up period of 10 years. The maximum analytical sample size for the analysis using ELSA was n = 8127.

Health and Retirement Study (HRS)

We replicated the analyses of ELSA using HRS, a comparable representative longitudinal study of older adults in the US, that collected a wider range of psychological well-being related measures. HRS recruited participants in 1992 (Wave 1) with biennial follow-ups conducted from 1994 (Wave 2) to 2020 (Wave 15). From 2006 (Wave 8), HRS expanded its content by including a set of biomarker, physical, and psychosocial assessments through a mixed-mode design for follow-up. Half of the participants were randomly selected for the first enhanced face-to-face interview (EFTF) at Wave 8 for the expanded content and the other half only participated in the core interview. From Wave 9, the data collection method was swapped between the two half-sample groups [36]. For our study, we combined the two half EFTF samples from Wave 9 (2008) and Wave 10 (2010) as a baseline because psychological well-being related measures were collected using the same tools. Follow-up assessments of NCDs started from Waves 10 and 11 for participants with baseline measures at Waves 9 and 10, respectively, and up to Wave 15 with a maximum follow-up period of 10 years. The maximum analytical sample size was n = 12,477.

Variables

Exposure: obesity

An objective measure of body mass index (BMI) in kg/m2 was used to define obesity at baseline in ELSA and HRS (see Supplementary Materials for more information). Following previous studies [37, 38], our analysis mainly compared the risk of develo** an NCD between participants with obesity (BMI ≥ 30) and normal weight (BMI 18.5–24.9). If we found no evidence of relative risk based on this comparison, we compared Class II & III obesity (BMI ≥ 35) with normal weight. We excluded participants with underweight (BMI < 18.5) as some diseases can cause weight loss and then may increase the risk of ill health in participants with underweight [39].

Outcomes: non-communicable diseases (NCDs)

Following a recently published study that examined multimorbidity based on 14 health outcomes available in ELSA [40], our study selected seven health outcomes or NCDs that have been found to be associated with both obesity and psychological well-being related measures: hypertension, heart disease, stroke, diabetes mellitus, arthritis, cancer, and dementia or memory-related disease (see Table A1 in Supplementary Materials). For mediation analyses, we examined NCDs that were predicted by obesity at baseline. Most NCDs were defined based on self-reported doctor diagnosis only, whilst some combined a self-reported doctor-diagnosis measure with other assessments (e.g., blood pressure for hypertension and fasting plasma glucose or HbA1c for diabetes). Table A2 presents how each NCD was determined in ELSA and HRS.

Candidate mediators: psychological well-being related measures

Table A3 presents a list of psychological well-being related measures available at baseline in ELSA (n = 7) and HRS (n = 15). Five psychological well-being related measures in ELSA were also available for analysis in HRS (see Supplementary Material for full information). All the psychological well-being related measures were standardised using z-scores to allow comparison across different metrics.

For the main analysis, we developed a composite index of overall psychological well-being measures separately in ELSA and HRS. Following our previous approach [41], we used exploratory factor analysis (EFA) to retain psychological well-being related measures that loaded onto the same underlying single factor, defined as having an item loading ≥0.55 [42]. In ELSA, five psychological well-being related measures were combined into an index (depressive symptoms, enjoyment of life, eudemonic well-being, life satisfaction, and loneliness). In HRS, ten psychological well-being related measures were combined into an index (depressive symptoms, life satisfaction, loneliness, positive affect, negative affect, purpose in life, anxiety, hopelessness, pessimism, and personal constraint, otherwise known as lack of self-control). Some psychological well-being related measures (e.g., enjoyment of life, eudemonic well-being, life satisfaction) were reverse scored to be consistent with other measures that were in the direction of lower psychological well-being (e.g., depressive symptoms) and then z-score transformed. This index of overall psychological well-being was calculated separately in each study by re-standardising average standardised scores of the retained psychological well-being related measures. A higher index indicated lower overall psychological well-being.

Following evidence of a statistically significant association between obesity and an NCD, mediation by the index of overall psychological well-being measures was tested in the main analysis. The benefit of this index approach is that it provides a more complete picture of overall psychological well-being in individual participants and addresses problems associated with examining a large number of measures in concert (e.g., multi-collinearity, model overfitting). However, additional mediation analyses for individual psychological well-being related measures that met preconditions for successful mediation were also conducted. We included an individual psychological well-being related measure if that measure was associated with both obesity and an NCD.

Covariates

Sociodemographic covariates that were controlled in the analysis included age (in years), sex (male, female), paid employment status (yes, no), ethnicity (White, non-White), marital status (single/never married, married/cohabiting, and separated/divorced/widowed), and educational level: the completion of degree-level qualification (yes; no) in ELSA (e.g., as in [11]) and the total number of years in education in HRS (e.g., as in [10]). We also controlled total household wealth (net non-pension wealth) in both studies that was transformed into quintiles (e.g., as in [10]).

Data analysis

Main analyses

We used Cox proportional hazard regression models to examine the associations between obesity at baseline and the incidence of each NCD, controlling for sociodemographic covariates. Survival time was calculated from the baseline interview date to the date of diagnosis or follow-up interview when an NCD was reported for the first time after the baseline (e.g., as in [43]). For each regression model predicting an NCD, participants who had that condition before or at baseline were excluded. We also used Cox models to evaluate the associations between the index of overall psychological well-being, individual psychological well-being related measures at baseline, and the incidence of NCDs. Findings were presented as hazard ratios (HR) along with 95% confidence intervals (CI) and p values. In addition, linear regression models were used to examine the cross-sectional association between obesity and psychological well-being related measures as part of pre-mediation condition analyses. Regression coefficient (β), 95% CI, and p values were presented as the results.

We assessed mediation by an index of overall psychological well-being if we found any evidence of the association between obesity and an NCD. We used causal mediation analysis to conduct mediation analysis (see Supplementary Materials for full information). Findings were presented as the overall proportion of the association due to mediation along with 95% CI and p values. Supplementary mediation analyses by each individual psychological well-being related measure were conducted if preconditions for successful mediation were satisfied. To address potential selection bias due to missing observations, we used the inverse probability weighting approach [44, 45] (see Supplementary Materials for full information).

We set p < 0.05 for the main regression analysis of the associations between obesity, index of overall psychological well-being, and NCDs, and mediation analysis by the index. To correct for multiple comparisons, p < 0.01 was set for supplementary analyses for individual psychological well-being related measures, including regression analyses for examining preconditions for successful mediation (associations between individual psychological well-being related measures and (1) obesity and (2) NCDs) and single mediation analyses by each psychological well-being related measure. The same significance level (p < 0.01) was also applied for the following additional analyses.

Additional analyses

We conducted additional analyses, including the outcome assessed as the total number of NCDs identified during follow-up in both studies and comparative analysis for ELSA by linking ELSA with hospital admissions data (Hospital Episode Statistics). To better understand potential independent vs. related effects of psychological well-being related measures and body weight on NCDs, we also explored if weight change (measured as change in BMI) between waves in part explained any prospective associations between individual psychological well-being related measures at baseline and NCDs (see Supplementary Materials for full information). We also conducted (non-preregistered) interaction analyses between obesity status and index of overall psychological well-being related measures in predicting NCDs in both studies.

Results

Characteristics of participants

Table 1 shows that participants from ELSA and HRS were comparable in terms of age and sex. The proportions of participants who were non-White and had obesity were higher in HRS than in ELSA. HRS participants had higher prevalence of all NCDs at baseline vs. ELSA participants. Likewise, the incidence of NCDs was generally higher in HRS during the follow-up period.

Findings from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA)

Table 2 shows that obesity (vs. normal weight) was associated with increased risk of hypertension (HR = 1.52; 95% CI = 1.25, 1.85), heart disease (HR = 1.45; 95% CI = 1.19, 1.76), diabetes (HR = 4.23; 95% CI = 2.98, 6.01), and arthritis (HR = 1.82; 95% CI = 1.49, 2.23), and these association were also independent of the index of overall psychological well-being. No risk differences in develo** stroke, cancer, and memory-related disease were observed between participants with obesity vs. normal weight (Models 1 and 2), or between those with Class II & III obesity vs. normal weight (Table B1).

Table 3 indicates that index of overall psychological well-being was associated with risk of hypertension, heart disease, stroke, arthritis, and memory-related disease, independently of obesity status. Individual psychological well-being related measures (e.g., depressive symptoms, enjoyment of life) were also independently associated with those NCDs (p < 0.01) (Table B2). We found stronger associations between obesity and psychological well-being related measures when Class II & III obesity and normal weight were compared (Table B3), as opposed to when all obesity and normal weight were compared.

We conducted mediation analyses for NCDs that were associated with obesity. As our findings indicated stronger associations between Class II & III obesity (vs. normal weight) and psychological well-being related measures, mediation analyses were conducted comparing both obesity vs. normal weight, and Class II & III obesity vs. normal weight. However, findings from causal mediation analysis consistently indicated no evidence of mediation by the index of overall psychological well-being (Table 4) or by individual psychological well-being related measures of which preconditions for mediation analysis were satisfied (Table B4).

Obesity (vs. normal weight) was also associated with the cumulative number of NCDs across the follow-up period (IRR = 1.35; 95% CI = 1.26, 1.44) (Table B5). For psychological well-being related measures, none were associated with the cumulative number of NCDs at p < 0.01 (Table B6). No mediation analysis was conducted for the number of NCDs because not all preconditions for successful mediation were satisfied (see Tables B3, B5 and B6 for more information). Furthermore, we did not find associations between psychological well-being related measures and weight change (Table B7) and weight change were not associated with the incidence of any NCDs (Table B8), and therefore, mediation by weight change was not examined. When the incidence of NCDs in ELSA was classified on the basis of hospital admissions data, results were largely consistent with obesity being a risk factor for NCD incidence but there being no mediation by psychological well-being related measures; obesity (vs. normal weight) was associated with hypertension (HR = 2.23; 95% CI = 1.63, 3.04) and diabetes incidence (HR = 3.80; 95% CI = 2.38, 6.09) with no evidence of mediation (Tables B9–B17). As we found no evidence for mediation, we conducted interaction analyses using survey data and found that the index of overall psychological well-being did not moderate most associations between obesity and NCDs. The exception was memory-related disease (Table B18), whereby the association between obesity status and disease development risk was higher among participants with lower overall psychological well-being (a higher index score).

Findings from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS)

Similar to ELSA, obesity (vs. normal weight) was associated with increased risk of hypertension (HR = 1.43, 95% CI = 1.18, 1.74), heart disease (HR = 1.27, 95% CI = 1.07, 1.51), diabetes (HR = 2.79, 95% CI = 2.22, 3.51), and arthritis (HR = 1.42, 95% CI = 1.18, 1.70), and these association were independent of the index of overall psychological well-being (Table 5). While there were no risk differences in develo** stroke and cancer between participants with obesity vs. normal weight, participants with obesity tended to have lower risk of develo** memory-related disease. For most of the NCDs, findings remained when Class II & III obesity and normal weight were compared (Table C1).

The index of overall psychological well-being was associated with heart disease, stroke, arthritis, and memory-related disease, independently of obesity status in HRS (Table 6). These findings were largely consistent when individual psychological well-being related measures were examined (Table C2). In addition, stronger associations between obesity and psychological well-being related measures appeared when Class II & III obesity and normal weight were compared (Table C3), as opposed to all obesity vs. normal weight. Findings from mediation analyses in HRS were similar to ELSA. The associations between obesity and increased risk of some NCDs were not mediated by index of overall psychological well-being (Table 7) and individual psychological well-being related measures that satisfied pre-mediation conditions (Table C4).

When the outcome was assessed as the cumulative number of NCDs, obesity (IRR = 1.13; 95% CI = 1.11, 1.16) and psychological well-being related measures (e.g., index of overall psychological well-being measures, life satisfaction, anxiety) were associated with the cumulative number of NCDs (Tables C5 and C6, respectively). Psychological well-being related measures did not mediate the association between obesity and the number of NCDs (Table C7). Furthermore, we did not assess mediation by change in BMI between waves on the association between baseline psychological well-being related measures and NCDs as preconditions were not satisfied (see Tables C8 and C9). In HRS, no evidence for the interaction between obesity and index of overall psychological well-being was observed in predicting NCDs (Table C10).

Discussion

In UK (ELSA) and US (HRS) samples of older adults, obesity (vs. normal weight) was consistently associated with an increased risk of develo** a range of NCDs (hypertension, heart disease, diabetes, and arthritis). We examined the potential role of a wide range of psychological well-being related measures in explaining these obesity-NCD risks. Statistical evidence indicated that a large number of the psychological measures examined were inter-related and corresponded to an overall factor of psychological well-being. This index of overall psychological well-being and a number of the psychological well-being related measures when treated individually were associated with an increased risk of heart disease, stroke, arthritis, and memory-related disease, independently of obesity status. However, there was no evidence that the reason obesity was associated with increased NCD risk was in part explained by psychological well-being related measures (as an overall index or individually) associated with obesity in both ELSA and HRS. Findings were consistent across additional analyses, including when the cumulative number of NCDs developed were considered as the outcome, and when NCDs derived from linked hospital admissions data were used (ELSA). Additionally, we found no evidence that BMI change explained why some individual psychological well-being related measures increased risk of NCD incidence. There was weak evidence for psychological well-being related measures moderating the associations between obesity and NCDs. In summary, obesity and psychological well-being may independently and additively increase risk of develo** NCDs.

The psychological burden of obesity due to exposure to chronic stressors (e.g., weight stigma) has been proposed to have future health impacts [17, 18]. In line with this, a previous study reported that having excess visceral fat is associated with weight stigma across BMI categories, particularly in women [46]. In our analyses, the associations between obesity and psychological well-being related measures tended to be more salient in participants with obesity Class II & III vs. normal weight. This may be because participants with obesity Class II & III experience more stigmatisation [19]. Impaired psychological well-being, as evidenced by depressive symptoms for example, may lead to dysregulation of multiple physiological functioning [17, 31, 47], leading to the proposal that obesity related increased risk of disease may be explained by (mediated) the psychosocial burden of obesity [48, 49]. Contrary to this proposition, our findings indicated that psychological well-being related measures did not explain why obesity was associated with risk of disease incidence. This aligns with our previous findings that a range of psychological well-being related measures did not convincingly explain worsening physiological health in the UK and the US older adults with obesity [10], with the possible exception of experiencing weight discrimination contributing to a modest amount of obesity-related worsening of physiological health over time. In the present analyses, we were unable to examine reported experiencing of weight discrimination as a potential mediator of obesity related NCD incidence, because of a lack of weight discrimination measure at baseline and concern that the timing of measurement in waves may produce results prone to reverse causality (e.g., weight gain from baseline onwards leading to perceived weight discrimination and NCD incidence). Given the likely damaging effects of experiencing discrimination [50] this remains an important variable to consider in the future.

Based on the present results, the prospective association between obesity and NCDs in the present study may be largely driven by a direct effect of adiposity. Visceral adipose tissue is highly metabolically active and linked to constant free fatty acids (FFA) release that leads to the development of metabolic syndrome, including systemic inflammation, hyperinsulinemia, dyslipidaemia, and atherosclerosis [5, 6, 51]. Even though overall obesity is generally correlated with central or abdominal obesity (i.e., excessive concentration of visceral body fat); some individuals who fall within the obesity category may not have abdominal obesity [52]. Individuals with normal BMI but with excess visceral fat tend to have a more adverse metabolic profile than those with elevated BMI (≥25 kg/m2) but with low visceral fat [53]. Furthermore, an unhealthy metabolic profile has been found to be associated with worsening physical health, independently of obesity status. For example, dyslipidaemia (e.g., increasing total cholesterol, decreasing high-density lipoprotein (HDL)) is monotonically associated with increased risk of cardiovascular disease in all BMI groups [54].

It is important to note that null findings on mediation by psychological well-being related measures in this study may be also due to the complex association between obesity and psychological well-being related measures in older age participants. Evidence from a meta-analysis indicates that current obesity status may be a protective factor against depression in older adults [55]. Older adults may experience unintentional weight loss due to some health conditions that may be also associated with obesity (e.g., cancer, gastrointestinal disease, cognitive impairment) [56], and this obesity-related morbidity has been found to be related to reduced psychological well-being [57]. Examining current weight status alone in older age participants may fail to address the role of previous obesity status in initiating subsequent adverse physical consequences that contribute to weight loss and worse psychological outcomes [41].

Aside from obesity, other physical and social conditions also contribute to impaired psychological well-being in older adults, including chronic diseases, chronic pain and disability, changes in financial circumstances and social status [58]. Worsening physiological health may partly explain the impact of impaired psychological well-being on future NCDs. In line with this, metabolic syndrome is more common in individuals with depression [32]. A previous study also indicated that a range of psychological well-being related measures was associated with physiological health in the UK older adults independent of obesity [10]. In addition, some mechanisms through vascular disease and hippocampal atrophy have been proposed as pathways linking depression to memory-related disease (e.g., dementia) [59]. Moreover, psychological well-being related measures may also be indirectly associated with NCDs through promoting health risk behaviours, including unhealthy eating [33], physical inactivity [34], and smoking [60].

Strengths and limitations

Our study is the first comprehensive assessment of the role of a wide range of psychological well-being related measures in explaining obesity-related NCD incidence. We used two large longitudinal datasets from the UK and the US to examine the generalisability of the findings. Limitations included use of self-reported NCDs in primary analyses for ELSA and HRS. However, the findings remained the same in analyses where linked hospital admission data were available to diagnose NCDs (ELSA). Nevertheless, NCDs derived from hospital admissions data may be under-reported as individuals with NCD conditions may be treated in primary care for these conditions, as opposed to being hospitalised. In addition, this study only included older age (≥50 years) and mostly White participants, and therefore, future studies will benefit from replicating the analyses in younger and more ethnically diverse participants. Like in the majority of studies examining the obesity-related disease burden we investigated how baseline obesity status predicted future disease risk. However, future work examining both current and history of obesity will be important to understand the impact of obesity on psychological well-being related measures and subsequent health outcomes developed in older adults. Psychological well-being related measures were examined at a single time-point in this study, and therefore modelling the potential dynamic nature of the association between body weight, psychological well-being, and the onset of NCDs was not possible. Future work will benefit from understanding this potential dynamic association.

Conclusion

The prospective association between obesity and risk of develo** NCDs were not explained by psychological well-being related measures. Obesity and psychological well-being may independently and additively increase risk of develo** NCDs.

Data availability

Data are available online (ELSA: https://doi.org/10.5255/UKDA-SN-5050-25; HRS: https://hrsdata.isr.umich.edu/data-products/rand) with the permission of the data custodians.

References

Baker C. Research briefing: obesity statistics. House of Commons Library; 2022.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Overweight and obesity: adult obesity facts. 2022.

GBD Obesity Collaborators, Afshin A, Forouzanfar MH, Reitsma MB, Sur P, Estep K, et al. Health effects of overweight and obesity in 195 countries over 25 years. N. Engl J Med. 2017;377:13–27.

Kitahara CM, Flint AJ, Berrington de Gonzalez A, Bernstein L, Brotzman M, MacInnis RJ, et al. Association between class III obesity (BMI of 40–59 kg/m2) and Mortality: a pooled analysis of 20 prospective studies. PLoS Med. 2014;11:e1001673.

Chait A, den Hartigh LJ. Adipose tissue distribution, inflammation and its metabolic consequences, including diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2020;7:22.

Jensen MD. Is visceral fat involved in the pathogenesis of the metabolic syndrome? Human model. Obesity. 2006;14:20s–4s.

Zhang L, Zhang W-H, Zhang L, Wang P-Y. Prevalence of overweight/obesity and its associations with hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, and metabolic syndrome: a survey in the suburban area of Bei**g, 2007. Obes Facts. 2011;4:284–9.

Rossi RC, Vanderlei LCM, Gonçalves ACCR, Vanderlei FM, Bernardo AFB, Yamada KMH, et al. Impact of obesity on autonomic modulation, heart rate and blood pressure in obese young people. Auton Neurosci. 2015;193:138–41.

Choi J, Joseph L, Pilote L. Obesity and C-reactive protein in various populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2013;14:232–44.

Putra IGNE, Daly M, Sutin A, Steptoe A, Robinson E. Psychological pathways explaining the prospective association between obesity and physiological dysregulation. Health Psychol. 2023;42:472–84.

Daly M, Sutin AR, Robinson E. Perceived weight discrimination mediates the prospective association between obesity and physiological dysregulation: evidence from a population-based cohort. Psychol Sci. 2019;30:1030–9.

Yousufuddin M, Takahashi PY, Major B, Ahmmad E, Al-Zubi H, Peters J, et al. Association between hyperlipidemia and mortality after incident acute myocardial infarction or acute decompensated heart failure: a propensity score matched cohort study and a meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e028638.

Yao X, Tian Z. Dyslipidemia and colorectal cancer risk: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Cancer Causes Control. 2015;26:257–68.

Peng J, Zhao F, Yang X, Pan X, **n J, Wu M, et al. Association between dyslipidemia and risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus in middle-aged and older Chinese adults: a secondary analysis of a nationwide cohort. BMJ Open. 2021;11:e042821.

Giles JT, Bartlett SJ, Andersen R, Thompson R, Fontaine KR, Bathon JM. Association of body fat with C-reactive protein in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:2632–41.

Kravitz BA, Corrada MM, Kawas CH. Elevated C-reactive protein levels are associated with prevalent dementia in the oldest-old. Alzheimers Dement. 2009;5:318–23.

Tomiyama AJ. Stress and obesity. Annu Rev Psychol. 2019;70:703–18.

Puhl RM, Himmelstein MS, Pearl RL. Weight stigma as a psychosocial contributor to obesity. Am Psychol. 2020;75:274–89.

Spahlholz J, Baer N, König HH, Riedel-Heller SG, Luck-Sikorski C. Obesity and discrimination—a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Obes Rev. 2016;17:43–55.

Robinson E, Sutin A, Daly M. Perceived weight discrimination mediates the prospective relation between obesity and depressive symptoms in U.S. and U.K. adults. Health Psychol. 2017;36:112–21.

Gariepy G, Nitka D, Schmitz N. The association between obesity and anxiety disorders in the population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Obes. 2010;34:407–19.

Pasco JA, Williams LJ, Jacka FN, Brennan SL, Berk M. Obesity and the relationship with positive and negative affect. Aust NZ J Psychiatry. 2013;47:477–82.

Katsaiti MS. Obesity and happiness. Appl Econ. 2012;44:4101–14.

Shay M, MacKinnon AL, Metcalfe A, Giesbrecht G, Campbell T, Nerenberg K, et al. Depressed mood and anxiety as risk factors for hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2020;50:2128–40.

Gan Y, Gong Y, Tong X, Sun H, Cong Y, Dong X, et al. Depression and the risk of coronary heart disease: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:371.

Pérez-Piñar M, Ayerbe L, González E, Mathur R, Foguet-Boreu Q, Ayis S. Anxiety disorders and risk of stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Psychiatry. 2017;41:102–8.

Kan C, Silva N, Golden SH, Rajala U, Timonen M, Stahl D, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the association between depression and insulin resistance. Diab Care. 2013;36:480–9.

Fakra E, Marotte H. Rheumatoid arthritis and depression. Jt Bone Spine. 2021;88:105200.

Wang Y-H, Li J-Q, Shi J-F, Que J-Y, Liu J-J, Lappin JM, et al. Depression and anxiety in relation to cancer incidence and mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Mol Psychiatry. 2020;25:1487–99.

Stafford J, Chung WT, Sommerlad A, Kirkbride JB, Howard R. Psychiatric disorders and risk of subsequent dementia: systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2022;37:1–22.

Halaris A, Prochaska D, Stefanski A, Filip M. C-reactive protein in major depressive disorder: promise and challenge. J Affect Disord Rep. 2022;10:100427.

Moradi Y, Albatineh AN, Mahmoodi H, Gheshlagh RG. The relationship between depression and risk of metabolic syndrome: a meta‐analysis of observational studies. Clin Diab Endocrinol. 2021;7:4.

Paans NPG, Bot M, Brouwer IA, Visser M, Roca M, Kohls E, et al. The association between depression and eating styles in four European countries: the MooDFOOD prevention study. J Psychosom Res. 2018;108:85–92.

Matta J, Hoertel N, Kesse-Guyot E, Plesz M, Wiernik E, Carette C, et al. Diet and physical activity in the association between depression and metabolic syndrome: constances study. J Affect Disord. 2019;244:25–32.

Banks J, Batty GD, Breedvelt J, Coughlin K, Crawford R, Marmot M, et al. English Longitudinal Study of Ageing: Waves 0-9, 1998-2019. [data collection]. 38th ed. UK Data Service. SN; 2023.

Sonnega A, Faul JD, Ofstedal MB, Langa KM, Phillips JWR, Weir DR. Cohort profile: the Health and Retirement Study (HRS). Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43:576–85.

Kim MS, Kim WJ, Khera AV, Kim JY, Yon DK, Lee SW, et al. Association between adiposity and cardiovascular outcomes: an umbrella review and meta-analysis of observational and Mendelian randomization studies. Eur Heart J. 2021;42:3388–403.

Dobbins M, Decorby K, Choi BC. The association between obesity and cancer risk: a meta-analysis of observational studies from 1985 to 2011. ISRN Prev Med. 2013;2013:680536.

Roh L, Braun J, Chiolero A, Bopp M, Rohrmann S, Faeh D, et al. Mortality risk associated with underweight: a census-linked cohort of 31,578 individuals with up to 32 years of follow-up. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:371.

Ronaldson A, Arias de la Torre J, Bendayan R, Yadegarfar ME, Rhead R, Douiri A, et al. Physical multimorbidity, depressive symptoms, and social participation in adults over 50 years of age: findings from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Aging Ment Health. 2023;27:43–53.

Putra IGNE, Daly M, Sutin A, Steptoe A, Robinson E. The psychological legacy of past obesity and early mortality: evidence from two longitudinal studies. BMC Med. 2023;21:448.

Cleare S, Gumley A, Cleare CJ, O’Connor RC. An Investigation of the Factor Structure of the Self-Compassion Scale. Mindfulness. 2018;9:618–28.

Bu F, Zaninotto P, Fancourt D. Longitudinal associations between loneliness, social isolation and cardiovascular events. Heart. 2020;106:1394–9.

Mansournia MA, Altman DG. Inverse probability weighting. BMJ. 2016;352:i189.

Chesnaye NC, Stel VS, Tripepi G, Dekker FW, Fu EL, Zoccali C, et al. An introduction to inverse probability of treatment weighting in observational research. Clin Kidney J. 2022;15:14–20.

Keirns NG, Keirns BH, Sciarrillo C, Emerson S, Hawkins MA. Abstract 12419: Internalized weight stigma linked to greater visceral adiposity for women, but not men. Circulation. 2021;144:A12419.

Zhang M, Chen J, Yin Z, Wang L, Peng L. The association between depression and metabolic syndrome and its components: a bidirectional two-sample Mendelian randomization study. Transl Psychiatry. 2021;11:633.

Tomiyama AJ, Carr D, Granberg EM, Major B, Robinson E, Sutin AR, et al. How and why weight stigma drives the obesity ‘epidemic’ and harms health. BMC Med. 2018;16:123.

Tomiyama AJ. Weight stigma is stressful. A review of evidence for the Cyclic Obesity/Weight-Based Stigma model. Appetite. 2014;82:8–15.

Zhu X, Smith RA, Buteau E. A meta-analysis of weight stigma and health behaviors. Stigma Health. 2022;7:1–13.

Yki-Järvinen H. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease as a cause and a consequence of metabolic syndrome. Lancet Diab Endocrinol. 2014;2:901–10.

Powell-Wiley TM, Poirier P, Burke LE, Després J-P, Gordon-Larsen P, Lavie CJ, et al. Obesity and cardiovascular disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2021;143:e984–1010.

Thomas EL, Frost G, Taylor-Robinson SD, Bell JD. Excess body fat in obese and normal-weight subjects. Nutr Res Rev. 2012;25:150–61.

Hirakawa Y, Lam T-H, Welborn T, Kim HC, Ho S, Fang X, et al. The impact of body mass index on the associations of lipids with the risk of coronary heart disease in the Asia Pacific region. Prev Med Rep. 2016;3:79–82.

Yu M, Shi Y, Gu L, Wang W. Jolly fat” or “sad fat”: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the association between obesity and depression among community-dwelling older adults. Aging Ment Health. 2022;26:13–25.

McMinn J, Steel C, Bowman A. Investigation and management of unintentional weight loss in older adults. BMJ. 2011;342:d1732.

Frank P, Jokela M, Batty GD, Lassale C, Steptoe A, Kivimäki M. Overweight, obesity, and individual symptoms of depression: a multicohort study with replication in UK Biobank. Brain Behav Immun. 2022;105:192–200.

Rodda J, Walker Z, Carter J. Depression in older adults. BMJ. 2011;343:d5219.

Byers AL, Yaffe K. Depression and risk of develo** dementia. Nat Rev Neurol. 2011;7:323–31.

Joynt KE, Whellan DJ, O’Connor CM. Depression and cardiovascular disease: mechanisms of interaction. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54:248–61.

Acknowledgements

The English Longitudinal Study of Ageing is funded by the National Institute on Aging (R01AG017644) and by a consortium of UK Government Departments coordinated by the National Institute of Health and Care Research (198/1047). The Health and Retirement Study is sponsored by the National Institute on Aging (grant number NIA U01AG009740) and is conducted by the University of Michigan.

Funding

This work received funding from the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC), a part of the United Kingdom Research and Innovation (UKRI) (ES/V017594/1). The views stated in this work are of the authors only.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

I Gusti Ngurah Edi Putra: conceptualisation, methodology, project administration, data curation, formal analysis, visualisation, writing—original draft. Michael Daly: conceptualisation, methodology, funding acquisition, writing—review and editing. Angelina Sutin: conceptualisation, funding acquisition, writing—review and editing. Andrew Steptoe: conceptualisation, funding acquisition, writing—review and editing. Shaun Scholes: data curation, formal analysis, writing—review and editing. Eric Robinson: conceptualisation, methodology, project administration, supervision, funding acquisition, writing—review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study used data from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA) and the Health and Retirement Study (HRS). Each ELSA wave obtained ethics approval from different UK research ethics committees (https://www.elsa-project.ac.uk/ethical-approval). HRS was approved by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board (IRB). All participants in each study provided informed consent.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Putra, I.G.N.E., Daly, M., Sutin, A. et al. Obesity, psychological well-being related measures, and risk of seven non-communicable diseases: evidence from longitudinal studies of UK and US older adults. Int J Obes (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-024-01551-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-024-01551-1

- Springer Nature Limited