Abstract

Addiction is a chronic disorder involving recurring intoxication, withdrawal, and craving episodes. Esca** this vicious cycle requires maintenance of abstinence for extended periods of time and is a true challenge for addicted individuals. The emergence of depressive symptoms, including social withdrawal, is considered a main cause for relapse, but underlying mechanisms are poorly understood. Here we establish a mouse model of protracted abstinence to heroin, a major abused opiate, where both emotional and working memory deficits unfold. We show that delta and kappa opioid receptor (DOR and KOR, respectively) knockout mice develop either stronger or reduced emotional disruption during heroin abstinence, establishing DOR and KOR activities as protective and vulnerability factors, respectively, that regulate the severity of abstinence. Further, we found that chronic treatment with the antidepressant drug fluoxetine prevents emergence of low sociability, with no impact on the working memory deficit, implicating serotonergic mechanisms predominantly in emotional aspects of abstinence symptoms. Finally, targeting the main serotonergic brain structure, we show that gene knockout of mu opioid receptors (MORs) in the dorsal raphe nucleus (DRN) before heroin exposure abolishes the development of social withdrawal. This is the first result demonstrating that intermittent chronic MOR activation at the level of DRN represents an essential mechanism contributing to low sociability during protracted heroin abstinence. Altogether, our findings reveal crucial and distinct roles for all three opioid receptors in the development of emotional alterations that follow a history of heroin exposure and open the way towards understanding opioid system-mediated serotonin homeostasis in heroin abuse.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Drug abuse is a chronic brain disorder with devastating consequences for individuals and their social environment. Natural history of the disease typically consists in a vicious cycle. Positive subjective effects are experienced during drug intoxication, which are followed by emotional and physical signs of withdrawal when the drug is no longer available. These in turn feed into a ‘preoccupation’ stage, where drug craving induces drug-seeking behavior and precipitates relapse. Esca** this vicious cycle requires that prolonged abstinence be maintained, possibly throughout life. In humans, it is well known that drug craving progressively increases over the several first weeks of abstinence and remains high for extended periods of time (Koob and Volkow, 2010).

Several causes contribute to interrupt drug abstinence. External factors, such as life stress events and drug-associated contexts (Koob and Volkow, 2010), are well-studied determinants for relapse. Another key factor, which is less understood, is the alteration of emotional homeostasis during the course of the disease. Abstinence, notably from opiate addiction, is characterized by symptoms reminiscent of anxiety and depression, including lowered mood and anhedonia (Grella et al, 2009). Further, in addicted individuals, the development of depressive symptoms is associated with more severe clinical courses and lower social competence (Bakken et al, 2007). Antidepressant therapy has been used in this context, although with limited success (Nunes et al, 2004). Therefore, understanding long-term emotional consequences of drug abuse has major implications for the management of opiate addicts.

Several animal studies have modeled prolonged withdrawal from opiates. Data have shown decreased motivation for natural reinforcers (SI Pairs of unfamiliar mice, from different home cages but of similar treatment condition and weight, were placed simultaneously for 10 min in the open-field arena, indirectly lit at 50 lux. Our previous work indicates that both previous habituation to the arena and dim lighting favor SIs in poorly anxiogenic conditions (Goeldner et al, 2011). Using an ethological keyboard, we measured the number of occurrences and the total duration of SI behaviors (sniffing, following, and pawing contact), as well as of the individual grooming behavior. Mice were placed for 6 min into a glass cylinder (height, 27 cm; diameter, 18 cm) filled with 3.5 liters of water (23±1 °C), and immobility time was recorded during the last 4 min (Goeldner et al, 2010) by direct observation using an ethological keyboard. Latency to the first immobilization was also noted. Mice were individually placed in a Y-shaped apparatus consisting of three arms (placed at 120° from each other, 40 × 9 × 16 cm) and allowed to move freely (continuous procedure) for 5 min under moderate lighting conditions (100 lux in the center-most region). Specific motifs were placed on the walls of each arm, thus allowing visual discrimination, and extra-maze cues of the room were also visible from the maze. An arm entry was counted when the mouse had all four paws inside the arm. The sequence of successive entries into the three arms was scored for each mouse, and the YM performance, ie, the percentage of spontaneous alternation performance, was defined as the ratio of actual alternations to possible alternations ((total arm entries−2) × 100, see (Mandillo et al, 2008; Wall et al, 2003)). Sessions were conducted overnight (1800–0800 hours). On the first day of the experiment, mice were habituated to single housing in small cages with constant access to two drinking bottles, both containing water. On following days, one (Schlosburg et al, 2013) of the drinking bottles was randomly exchanged with a bottle containing sucrose solution. Based on our preliminary experiments and considering that genetic background strongly influences sucrose preference measures (Pothion et al, 2004), we used the following sucrose concentrations: 0.8% for 100% C57BL/6JCrl mice; and 2.5 and 3.5% for 50–50% C57Bl6J-129SvPas mice. Animals were presented with each sucrose solution for 2 days. Bottles were counterbalanced on the left and the right sides of the feeding compartment and alternated in position from day to day. Mice were grouped back in their home cages between overnight daily sessions. All bottles were weighed before and after each session to measure water and sucrose intakes for each individual mouse. Sucrose preference was calculated as: preference=(sucrose solution intake (ml)/total fluid intake (ml)) × 100. As described previously (Del Boca et al, 2012), recombinant adeno-associated viruses serotype 2 (AAV) were produced using the AAV helper-free system (Agilent) and plasmids encoding the reporter enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) or the Cre recombinase-eGFP fusion protein (Cre), driven by a CMV promoter. AAV titers were determined by quantitative PCR (qPCR) and adjusted to 3 × 1012 viral genome/ml. MORfl/fl mice received stereotactic infusions in the DRN (1.5 μl/15 min) (AP, −0.3 mm from lambda; ML, 0.0 mm; DV, +3.55) of AAV expressing either (i) the Cre fusion protein (AAV-Cre) or (ii) the eGFP only as a control (AAV-eGFP). MOR coupling to G-proteins was measured for each mouse individually using [35S]-GTPγS binding assay on brain homogenates upon stimulation with increasing concentrations of its specific agonist DAMGO, as described previously (Weibel et al, 2013). All data are expressed as mean±SEM. Statistical analysis was performed using analysis of variance (ANOVA) with between-subjects (heroin treatment, fluoxetine pellets, or genotypes) and within-subjects (sucrose concentration) factors, in accordance with the experimental design. As the effect of the duration of abstinence was analyzed across independent animal cohorts, this factor was treated as a between-subject factor. In case of significant interaction, multiple group comparisons were performed using Bonferroni’s post-hoc analysis. Statistical significance was defined as p<0.05.FS

Y-maze (YM)

Sucrose preference

Production of Viral Vectors

DRN Stereotaxy

Agonist-Stimulated [35S]-GTPγS Binding

Statistical Analysis

RESULTS

Protracted Heroin Abstinence Produces Long-Lasting Social, Depressive-Like, and Spatial Working Memory Deficits in Mice

The severity of physical dependence, as measured by acute naloxone-precipitated withdrawal, is a classical measure of chronic opiate effects. Therefore, to translate our morphine abstinence model to heroin, we first established a chronic intermittent heroin administration protocol that would induce physical dependence similar to our previous morphine protocol (Goeldner et al, 2011). Based on previous reports (Kest et al, 2002; Klein et al, 2008), we selected heroin doses divided by a factor of two (10–50 mg/kg) compared with morphine doses in our previous study (20–100 mg/kg). Although the signs of withdrawal qualitatively differed (Supplementary Table S1), the global scores for acute naloxone-precipitated withdrawal were comparable across the two regimens (Supplementary Figure S1). We therefore applied intermittent administration of escalating 10–50 mg/kg heroin doses throughout the study.

In all the subsequent experimental series, we used separate animal cohorts to (i) measure naloxone-precipitated withdrawal at the end of heroin exposure, in order to verify and quantify the extent of physical dependence, and (ii) analyze emotional-like responses and spatial working memory during protracted abstinence in animals that experienced spontaneous withdrawal from the chronic heroin treatment (ie, in the absence of naloxone injection).

We then investigated the kinetics of emotional-related behavioral modifications upon 1, 4, or 7 weeks of spontaneous withdrawal (see time-line in Figure 1a). This included assessing anxiety-like and depressive-like behaviors, as well as SIs. First, we found that heroin preexposure had no effect on anxiety-like behaviors in the open-field test and only led to slightly increased locomotor activity (Supplementary Figure S2). In the SI test, two-way ANOVA showed that total social exploration time (Figure 1b) was decreased by heroin preexposure (F(1,64)=44.1; p<0.001), but not by the duration of abstinence (F(2,64)=1.7; p=0.20), with a significant interaction between the two factors (F(2,64)=6.4; p=0.003). Post-hoc analysis revealed that heroin-pretreated pairs of mice interacted significantly less than saline-pretreated controls after 4 weeks (p<0.001) and 7 weeks (p<0.001), but not after 1 week (p=1.0), of abstinence. In addition, within heroin-pretreated groups, SI time was decreased in 4-week heroin-abstinent mice compared with the 1-week time point (p=0.026).

Social, depressive-like, and spatial working memory deficits develop during the 7 weeks of heroin abstinence. (a) Experimental procedure. Independent animal cohorts were used to assess each time point during heroin abstinence. Following repeated opiate injections, mice were maintained drug free for 1, 4, or 7 weeks. Then, emotional-like responses were evaluated using classical paradigms performed every other day, as previously described (Goeldner et al, 2011; Lutz et al, 2013b). Mice body weights were measured as indices of global opiate effects during chronic injections and abstinence (Supplementary Figure S4). In the social interaction test (SI; n=12 pairs of mice/treatment group/abstinence duration), during heroin abstinence, social avoidance progressively emerged, with decreased duration of social behaviors (b) and increased grooming (c). Stimulus mice for social interactions tests were used only once. Increased despair-like behavior was also detected following a 7-week abstinence period in the forced swim test (FS; n=24 mice/treatment group/abstinence duration), with both increased immobility (d) and decreased latency to first immobilization (e). In the sucrose-preference test (n=24 mice/treatment group/abstinence duration), there was no effect of heroin abstinence on hedonic tone (f). Finally, abstinent mice showed decreased working memory performance in the Y-maze (YM; n=24 mice/treatment group/abstinence duration) task (g). Values are mean±SEM.+p<0.05, ANOVA main effect of heroin; *p<0.001, post-hoc effects of heroin for each abstinence duration (see text for other post-hoc comparisons and also Supplementary Figure S2).

During the social encounter, individual self-grooming (Figure 1c) was also modified by heroin treatment (F(1,64)=59.0; p<0.001) and abstinence duration (F(2,64)=24.0; p<0.001), with a significant interaction (F(2,64)=16.1; p<0.001). Post-hoc analysis again indicated that grooming was significantly increased in heroin-treated pairs compared with saline controls after 4- (p<0.001) and 7- (p<0.001), but not 1-week (p=1.0), abstinence periods. In addition, grooming was significantly increased in 4- (p<0.001) and 7-week (p<0.001) heroin-abstinent groups compared with the 1-week heroin-abstinent group. Therefore, disruption of SIs appears after 4 weeks of heroin abstinence, as for morphine in our previous study. Further, data indicate that this behavioral modification persists for at least 3 additional weeks.

Second, we evaluated despair-like behaviors in both tail suspension (TS) and FS tests. In contrast with our morphine study, heroin treatment had no effect in the TS (Supplementary Figure S3a and b). In the FS, however, heroin significantly modified the duration of immobility (Figure 1d; F(1,135)=8.5; p=0.004). The abstinence duration had no effect on this parameter (F(2,135)=2.0; p=0.14), but there was a significant interaction (F(2,135)=3.4; p=0.038). Immobility was increased in heroin-abstinent mice after 7 weeks only (p=0.006), but not after 1 week (p=1.0) or 4 weeks (p=1.0) of abstinence. In saline-treated mice, duration of immobility was not modified in 7-week mice compared with 1- (p=0.07) and 4-week (p=0.08) groups. For the latency to first immobilization in the FS (Figure 1e), there was a significant effect of heroin treatment (F(1,135)=5.4; p=0.021) and of abstinence duration (F(2,135)=10.2; p<0.001), but no interaction (F(2,135)=1.1; p=0.33). Despair-like behaviors therefore develop during heroin abstinence but are only significantly detected at the 7-week time point. To further assess depression-related behaviors, we measured hedonic responses in abstinent mice, using the sucrose preference test (Figure 1f). We found no effect of heroin treatment (F(1,130)=0.16; p=0.69) or abstinence duration (F(2,130)=1.6; p=0.21) and no interaction (F(2,130)=0.36; p=0.70).

Considering that addicted patients frequently show cognitive deficits, even when abstinent (Ornstein et al, 2000; Rapeli et al, 2006), we finally examined abstinent mice in the YM task (Figure 1g). ANOVA revealed an effect of heroin abstinence for percentage of spontaneous alternations (F(1,135)=19.2; p=0<0.001), an index of spatial working memory. The abstinence duration had no effect (F(2,135)=0.07; p=0.93), but there was an interaction between these two factors (F(2,135)=4.2; p=0.017). As for sociability, post-hoc analysis showed that the working memory deficit was not detectable after 1 week (p=1.0) but emerged after 4 weeks (p=0.013) and persisted for at least 3 weeks (p=0.002). In this heroin model therefore, we detect a spatial working memory deficit, representing yet another aspect of protracted abstinence relevant to the human condition that we did not explore in our previous morphine study. Additional behavioral paradigms will be required to fully characterize the spectrum of cognitive deficits associated with opiate addiction (Ornstein et al, 2000) that may be addressed in our mouse model.

Delta and Kappa Opioid Receptors Bi-Directionally Regulate Social Behaviors and Hedonic Tone During Protracted Heroin Abstinence

Next, we explored contributions of DOR and KOR in heroin abstinence. These two receptors are not direct molecular targets for heroin but strongly regulate endogenous opioid physiology and contribute, yet very differently, to addictive behaviors and mood disorders. Antidepressant-like DOR and prodepressant-like KOR activities are now well established (Lutz and Kieffer, 2013a) but have not been examined in the context of heroin abstinence.

Naive DOR KO mice show increased emotional vulnerability (Lutz and Kieffer, 2013a). We therefore tested the hypothesis that mutant mice would show enhanced mood deficits after prolonged heroin abstinence. In the first group of mice, we measured precipitated withdrawal after heroin chronic treatment (Figure 2a and Supplementary Table S2). Heroin had a strong effect (F(1,33)=42.4; p<0.001), but there was no effect of genotype (F(1,33)=1.8; p=0.19) and no interaction (F(1,33)=1.6; p=0.22), indicating that physical dependence develops normally in DOR KO mice. In the second cohort of animals, we measured social behavior after a 4-week abstinence period. Social interactions (Figure 2b, left panel) were decreased by heroin (F(1,54)=20.8; p<0.001), regardless of the genotype (F(1,54)=2.0; p=0.17), therefore no enhancement of social deficits could be detected in mutant mice, at least under our experimental conditions. We also measured hedonic responses in abstinent mice, using the sucrose preference test (Figure 2b, right panel). Interestingly, we detected a significant interaction between genotype and heroin treatment (F(1,55)=4.6; p=0.036), as well as an effect of genotype (F(1,55)=8.5; p=0.005), in addition to the expected effect of sucrose concentration (F(1,55)=6.6; p=0.013)). At the 2.5% concentration, within-group comparisons showed a significant effect of heroin in DOR KO (p=0.036) but not in WT mice (2.5%, p=1.0). Importantly, there was no significant difference between WT-saline and DOR KO-saline mice at any of the two concentrations (2.5%, p=1.0; 3.5%, p=1.0), suggesting that the main effect of genotype is fully explained by its interaction with heroin treatment. Together, data indicate that DOR KO mice develop a more severe heroin abstinence syndrome, as social impairment is accompanied by anhedonia-like symptom. In conclusion, DOR activity does not significantly contribute to physical signs of heroin dependence but controls hedonic tone in heroin abstinence.

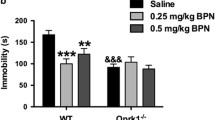

During heroin abstinence, delta opioid receptor (DOR) activity prevents the emergence of anhedonia-like symptom, and kappa opioid receptor (KOR) activity mediates the development of social withdrawal. Heroin physical dependence (a and c) and emotional consequences of 4-week abstinence (b and d) were studied in DOR knockout (KO) mice and in their wild-type (WT) littermates (a and b), as well as in KOR knockout (KO) mice and in their wild-type (WT) littermates (c and d). Naloxone-precipitated withdrawal, as a measure of physical dependence achieved at the end of opiate exposure, and the analysis of emotional-like behaviors during protracted abstinence, after spontaneous heroin withdrawal had occurred (no naloxone), were performed in separate animal cohorts. In DOR KO mice, (a) acute heroin withdrawal (n=8–10 mice/treatment group/genotype) and (b, left panel) social avoidance following a 4-week abstinence period (n=14–15 mice/treatment group/genotype) are comparable to levels in WT controls. In contrast, (b, right panel) decreased sucrose preference specifically developed in DOR KO but not in WT mice during heroin abstinence (n=14–15 mice/treatment group/genotype). In KOR KO mice, (c) physical dependence to heroin is slightly decreased (n=8–10 mice/treatment group/genotype), and (d, left panel) social avoidance is fully prevented (n=16–18 mice/treatment group/genotype). No modification of sucrose preference (d, right panel) is observed for KOR KO mice under our experimental conditions (n=16–18 mice/treatment group/genotype). Values are mean±SEM.+p<0.001, ANOVA main effects of heroin; *p<0.01, post-hoc comparisons between the saline and heroin groups; #p<0.05, post-hoc comparisons between the saline and heroin groups within each genotype.

Contrasting with DOR KO mice, naive KOR KO mice show no mood phenotype under basal conditions but display attenuated responses to several stressors (Lutz and Kieffer, 2013a). We therefore tested the hypothesis that KOR KO mice would be resistant to mood alterations after protracted heroin abstinence. In the first cohort, we found a significant genotype effect (F(1,30)=6.8; p=0.014) on physical withdrawal signs (Figure 2c and Supplementary Table S3), in addition to a strong heroin effect (F(1,30)=74.9; p<0.001) and a significant interaction (F(1,30)=7.2; p=0.011). Post-hoc comparisons indicated that physical dependence is decreased in heroin-pretreated KOR KO mice compared with heroin-pretreated WT mice (p=0.004), consistent with previous results for morphine (Simonin et al, 2006). Heroin abstinence was then studied in the second cohort. In the SI test (Figure 2d, left panel), there was a significant interaction between factors (F(1,65)=18.1; p<0.001), with an effect of treatment (F(1,65)=11.0; p=0.002) but not genotype (F(1,65)=1.6; p=0.21). Post-hoc analysis revealed that heroin abstinence significantly decreased SIs in WT mice (p<0.001), and this effect was absent in KOR KO (p=1.0). In the sucrose preference test (Figure 2d, right panel), sucrose concentration strongly influenced sucrose preference (F(1,54)=23.3; p<0.001), but there was no effect of genotype (F(1,66)=2.7; p=0.10) or heroin treatment (F(1,66)=0.16; p=0.69) and no interaction (F(1,66)=0.01; p=0.92), suggesting that sucrose preference did not differ between mutant and control animals. Thus KOR KO mice show reduced physical dependence to heroin and blunted abstinence-associated social deficits. We conclude that tonic KOR activity enhances acute withdrawal and is necessary to the development of SI deficits after protracted heroin abstinence.

Chronic Fluoxetine Prevents the Development of Social but not Spatial Working Memory Deficits in Heroin Abstinence

To test whether enhancing 5-HT function would prevent the development of social or working memory deficits, we examined consequences of a chronic antidepressant treatment during the 4-week abstinence period. We used fluoxetine, a prototypal SSRI, at a low dose (≈10 mg/kg/day, per os) that has no effect per se in saline-treated, control animals (Figure 3 and Supplementary Figure S6). In the SI test, heroin (F(1,27)=6.2; p=0.02), but not fluoxetine (F(1,27)=2.5; p=0.12), significantly modified social behaviors (Figure 3a). Importantly, there was an interaction between treatments (F(1,27)=4.9; p=0.035). Consistent with our kinetic experiments, heroin-pretreated mice pairs fed regular chow (heroin-control food) spent significantly less time interacting than saline controls (saline-control food; p=0.018). Chronic fluoxetine administration fully prevented this heroin-induced deficit, as interaction times between heroin-fluoxetine pairs and saline-fluoxetine pairs were not significantly different (p=1.0). During the social encounter, individual self-grooming (Figure 3b) was also modified by heroin (F(1,27)=4.8; p=0.038) and fluoxetine (F(1,27)=8.2; p=0.008), with a significant interaction (F(1,27)=4.5; p=0.042). Inter-group comparisons indicated that heroin-induced increase in grooming in control food mice (p=0.034) was absent in fluoxetine-fed mice (p=1.0, heroin–fluoxetine compared with saline–fluoxetine food pairs). Therefore, both decreased SIs and increased grooming observed in heroin-abstinent mice were prevented by chronic fluoxetine treatment.

Chronic antidepressant treatment prevents the development of social avoidance in heroin-abstinent mice. Following chronic saline or heroin injections, mice were fed fluoxetine-supplemented pellets (≈10 mg/kg/24 h) for 4 weeks, or nature pellets as controls, as previously described (Goeldner et al, 2011). In the social interaction (SI) test (n=7–8 pairs of mice/treatment group/food type), chronic treatment with fluoxetine prevented protracted heroin effects on (a) social and (b) individual behaviors. In contrast (c), fluoxetine did not prevent the effect of abstinence on working memory (n=15–16 mice/treatment group/food type). Values are mean±SEM.+p<0.001, ANOVA main effect of heroin; *p<0.01, post-hoc effects of heroin in control food mice; #p<0.05, post-hoc effects of fluoxetine in the heroin-treated groups.

In the YM (Figure 3c), while heroin still decreased spontaneous alternation (F(1,56)=17.7; p<0.001), there was no beneficial effect of fluoxetine (1,56)=1.4; p=0.24), and there was no interaction between factors (F(1,56)=0.44; p=0.51). Thus, 5-HT potentiation is ineffective on this aspect of the abstinence syndrome.

MOR Conditional Knockout (MOR cKO) in the DRN Prevents the Development of Social but not Spatial Working Memory Deficits in Heroin Abstinence

Fluoxetine mainly targets DRN 5-HT neurons. MOR is the main molecular target for 6-monoacetylmorphine and morphine, the two major active heroin metabolites in rodents (Andersen et al, 2009). Although this receptor is largely distributed throughout the nervous system, there is evidence that MORs expressed at the level of the DRN control firing rates of 5-HT neurons (Tao and Auerbach, 2002, 2005). We therefore tested the contribution of this particular MOR population to the development of emotional deficits in heroin abstinence.

To this aim, we produced cKO animals, which lack MORs specifically in the DRN (Figures 4 and 5), via injection of AAV-Cre in mice harboring a floxed MOR gene (MORfl/fl). First, we optimized stereotactic procedures so as to target the DRN while sparing adjacent regions (Figure 4b). We then infused either AAV-eGFP (MORfl/fl, control group) or AAV-Cre (MOR cKO group) and measured MOR signaling activity 4 weeks after surgery. In micro-dissected DRN homogenates (Figure 4c), [35S]-GTPγS binding increased with agonist concentration (F(2,56)=244.3; p<0.001) in control mice. This response was significantly lower in AAV-Cre-treated animals F(1,56)=19.4; p<0.001), corresponding to a 40% reduction in Emax (MORfl/fl 209.4±5.9%; MOR-cKO 165.5±8.4%). Post-hoc comparisons confirmed that [35S]-GTPγS binding was decreased at all the three agonist concentrations used (p<0.01). The genetic inactivation was restricted to DRN, as [35S]-GTPγS binding was unchanged in nearby structures, including the periaqueductal gray (Figure 4d; (F(1,56)=0.001; p=0.98)) and median raphe nucleus (Figure 4e; (F(1,56)=0.72; p=0.40)). A variety of experimental factors (notably the precision of DRN stereotaxy and micro-dissections), however, contribute to variability in the measure of MOR cKO efficacy. In subsequent experiments, therefore, the eGFP expression pattern was analyzed for each individual animal at the end of behavioral testing, and animals with mis-targeted or inefficient viral expression were excluded from the analyses.

Virally Cre-mediated recombination efficiently downregulates mu opioid receptors (MOR) in the dorsal raphe nucleus (DRN). (a) Experimental procedure. Independent animal cohorts (n=170 in total) were used for [35S]-GTPγS binding, heroin physical dependence, and heroin abstinence (see Figure 5). (b) Pattern of eGFP expression following stereotactic infusion of AAV–eGFP shows viral diffusion restricted to the DRN. (c) Four weeks following surgery, MOR activity was significantly reduced in the DRN, as shown by lower DAMGO-induced [35S]-GTPγS binding (n=14–16/group). In contrast, MOR signaling was preserved in the periaqueductal gray (d) or median raphe nucleus (e). Values are mean±SEM. #p<0.01, post-hoc comparison between the MORfl/fl and MOR cKO groups at each agonist concentration (M, molar concentration).

Conditional knockout of the mu opioid receptor (MOR cKO) in the dorsal raphe nucleus (DRN) prevents emergence of social avoidance during heroin abstinence. Naloxone-precipitated withdrawal (a) served as a measure of physical dependence achieved at the end of opiate exposure. Analyses of emotional-like behaviors during abstinence (b–d) were performed in separate animal cohorts, after they experienced spontaneous withdrawal from the chronic heroin treatment. MOR cKO in the DRN does not modify the severity of heroin physical dependence (n=6–7 mice/treatment group/virus type). In contrast, DRN MOR cKO in independent cohorts (n=9–13/treatment group/virus type) prevents the emergence of decreased social interactions (b) and decreases grooming duration (c), following a 4-week abstinence period. Finally, deleterious consequence of heroin abstinence on spatial working memory still manifested despite MOR cKO (d). Values are mean±SEM.+p<0.001, ANOVA main effects of heroin; ‡p<0.001, ANOVA main effect of genotype; *p<0.001, post-hoc comparison between saline- and heroin-treated mice.

We examined the first cohort of AAV-eGFP- and AAV-Cre-treated mice for physical dependence to heroin. ANOVA analysis of naloxone-precipitated withdrawal scores (Figure 5a and Supplementary Table S4) showed the expected strong effect of heroin (F(1,21)=50.4; p<0.001). There was no effect of genotype (F(1,21)=0.2; p=0.67) and no interaction (F(1,21)=0.01; p=0.91), indicating that MORs expressed by DRN neurons do not contribute to physical signs of acute heroin withdrawal. This is consistent with a previous report on conserved morphine physical dependence in mice lacking ascending serotonergic pathways (Zhao et al, 2007).

We then examined sociability in the second cohort. ANOVA indicated that the duration of social behaviors (Figure 5b) was significantly affected by heroin (F(1,38)=16.1; p<0.001)), with no effect of viral injection (F(1,38)=1.19; p=0.28), but a significant interaction between factors (F(1,38)=4.9; p=0.032). Post-hoc analysis showed that heroin significantly decreased social behaviors in MORfl/fl (saline VS heroin mice, p<0.001) but not in MOR cKO mice (saline VS heroin mice, p=1.0). Finally, individual grooming behavior (Figure 5c) was increased by heroin abstinence (F(1,38)=13.8; p<0.001), and decreased by AAV-Cre infusion (F(1,38)=4.8; p=0.04), with a trend toward an interaction between the two factors (F(1,38)=3.4; p=0.072). In contrast to control animals, therefore MOR cKO mice do not develop social deficits, demonstrating that activation of MOR at the level of the DRN is necessary for the emergence of social avoidance during heroin abstinence.

In the YM (Figure 5d), there was a strong effect of heroin (F(1,38)=23.5; p<0.001) but not of genotype (F(1,38)=0.29; p=0.59), with no interaction (F(1,38)=0.72; p=0.40). Therefore, DRN MORs do not seem to contribute to working memory impairment associated with heroin abstinence in this paradigm.

DISCUSSION

Our study establishes a behavioral mouse model of emotional dysfunction in heroin abstinence. This rodent model will be useful in the context of the highly prevalent association between addiction and depression (Darke et al, 2009). Although these two disorders clearly share bi-directional relationships, the clinical question remains to distinguish preexisting mood deficits in addicted individuals (self-medication) from mood deficits that develop upon repeated drug exposure and withdrawal cycles. In our animal model, we first demonstrate emergence of depressive-related traits following a history of heroin exposure. We then examine this phenomenon in KO models representing preexisting distinct states of emotional vulnerability (DOR KO mice) or resilience (KOR KO mice). Finally, we demonstrate that DRN MORs mediate the development of low sociability in heroin-abstinent animals, altogether revealing essential yet distinct roles of all three opioid receptors in mood control and social functioning during prolonged abstinence.

The heroin abstinence syndrome is characterized by low sociability after 4 weeks of abstinence. Interestingly, no deficit was observed after 1 week in any test, supporting the notion that dynamic adaptations incubate and develop along spontaneous prolonged withdrawal. These results demonstrate that repeated intermittent MOR over-stimulation by increasing heroin doses triggers long-term brain adaptations, which progressively lead to deficient SIs. Levels of sociability are known to be influenced by both mood- and anxiety-related traits in rodents. Here, we used a testing condition (low light and familiar context) that generates low levels of anxiety-like behaviors and thus promotes social investigation. Such testing procedure has been suggested to be more appropriate for the detection of social deficits associated with depressive-like state (eg, social withdrawal) rather than fear/anxiety-like state (File and Seth, 2003; Gururajan et al, 2010). Indeed, in the open-field test, heroin-abstinent mice displayed normal emotional-like responses, suggesting that the observed SI deficit may not be linked to heightened fear state. Furthermore, low sociability was detected at the 4-week time point and was then accompanied by increased despair-like behavior after 7 weeks, indicating that deficient sociability precedes mood disruption during on-going heroin abstinence. Emergence of this emotional syndrome strikingly parallels the observation of increasing relapse tendency in rodents withdrawn from opiate self-administration (Pickens et al, 2011) and supports the notion of ‘incubating’ drug craving. Possibly, emotional dysfunction may contribute to this time-dependent potentiation of relapse probability.

We found that heroin-abstinent mice show decreased performance in a YM task. This deficit reveals yet another facet of the abstinence syndrome, which we had not explored in our previous morphine study. This result suggests that, following repeated drug exposure, spatial working memory is impaired or alternatively that behavioral flexibility is decreased. Reduced performance in similar tasks was previously reported either immediately after opiate-induced activation of the MOR (Ukai et al, 2000) or after a 3-day withdrawal period (Ma et al, 2007), whereas later time points were not explored, to our knowledge. Here the deficit was detected after 4 and 7 weeks, but not 1 week, of abstinence, indicating that behavioral dysfunction develops with time, as for social withdrawal and despair-like behavior. In contrast to emotional alterations though, the YM deficit resisted to chronic fluoxetine treatment and developed despite conditional deletion of the MOR gene in DRN. These two lines of evidence strongly suggest that working memory impairment during heroin abstinence stems from MOR recruitment outside the DRN. MOR-dependent modulation of executive and memory functions has been demonstrated in other brain regions (medial septum, hippocampus, prefrontal cortex), in interaction with other neuro-modulatory systems (eg cholinergic transmission; Ragozzino and Gold, 1995). Additional studies will be needed to identify opioidergic circuits and transmitters involved in cognitive losses of heroin-abstinent animals.

Chronic activation of the MOR has been suggested to induce within-system adaptations, as revealed by increased expression of DOR (Hack et al, 2005) and KOR (Solecki et al, 2009). Considering that these two opioid receptors, respectively, show antidepressant- and prodepressant-like activities in pharmacology and genetic studies (Lutz and Kieffer, 2013a), we postulated that symptoms of heroin abstinence might be exacerbated, and attenuated, in DOR and KOR KO mice, respectively. Indeed, our results indicate that DOR KO mice, an emotionally vulnerable mutant line (Supplementary Figure S5a), react more severely to heroin abstinence and develop a robust anhedonia-like phenotype, considered a hallmark of depressive-like states across a variety of rodent paradigms. Several rodent studies support the use of DOR agonists as antidepressants, and clinical trials are on-going (Chu Sin Chung and Kieffer, 2013). Our data further indicate that these drugs may prove helpful for addicts suffering from depressive symptomatology.

In sharp contrast, the deleterious effect of heroin on sociability was fully abrogated in KOR KO mice. Several studies have shown that KOR contributes to the emergence of emotional deficits in rodent models of alcohol (Berger et al, 2013), nicotine (Smith et al, 2012) and cocaine addiction (Kallupi et al, 2013). Our data expand this growing body of evidence to opiate abuse and implicate KOR in long-lasting social aversion. Our study also strengthens the therapeutic potential of KOR antagonists and is coherent with clinical reports on beneficial effects of buprenorphine, a dual MOR agonist/KOR antagonist, in depressed addicts (Gerra et al, 2004).

Despite significant differences in morphine- and heroin-induced physical dependence and emotional impairments, abstinence from both drugs leads to social avoidance. Healthy social behaviors are essential to emotional regulation (Meyer-Lindenberg and Tost, 2012), and social avoidance has been extensively used in preclinical studies as a marker of pathological emotional states (Berton et al, 2012). Importantly, this robust phenotype can be fully blocked by chronic fluoxetine treatment, suggesting adaptations within 5-HT neurons. Because MOR stimulation upon heroin exposure represents the initial step towards molecular adaptations that ultimately lead to altered behavior, we tested whether abstinence deficits originate from the direct activation of MORs expressed at the level of the DRN. Our conditional genetic approach shows that decreased MOR signaling in the DRN does not modify physical dependence to heroin but is sufficient to fully prevent the emergence of social avoidance in heroin-abstinent mice. We therefore demonstrate that DRN MORs are essential for the disruption of social behaviors during heroin abstinence. Previous data showed that MORs expressed along mesolimbic dopaminergic pathways mediate rewarding properties of social stimuli (Trezza et al, 2010). Our finding further suggests that MORs in 5-HT circuits encode emotional components of social encounters, which may have implications outside the context of addiction. Notably, a recent report found that social adversity selectively recruits GABAergic DRN interneurons to mediate the expression of social avoidance (Challis et al, 2013). Therefore, we hypothesize that predominance of DRN MORs in these particular GABAergic neurons (Tao and Auerbach, 2005) may be essential in the control of social approach. In summary, our study uncovers for the first time an essential role for DRN MORs in the regulation of sociability and represents a first step towards the elucidation of MOR function at the interplay of rewarding and emotional properties of social stimuli.

Finally, the question arises of whether emotional deficits develo** along heroin abstinence are merely the direct result of acute physical withdrawal, considered an aversive experience, or arise from other adaptive processes in the brain. Considering the first hypothesis, it is possible that the milder physical withdrawal syndrome experienced by KOR KO mice following chronic heroin exposure may underlie, at least partly, the absence of social avoidance during abstinence in these mutants. Several observations of our study, however, favor the second hypothesis. In both DOR KO and DRN MOR cKO experiments, we demonstrate dissociation between physical dependence to heroin and emotional dysfunction during abstinence from the drug. Although acute signs of physical withdrawals were comparable to control groups in both genetic models, the abstinence period led to more or less severe outcomes in DOR KO and DRN MOR cKO mice, respectively. Therefore, emotional homeostasis during prolonged abstinence is not entirely determined by the severity of the acute withdrawal state. In addition, some of our recent data in 129SvPas mice show the development of despair-like behaviors despite an almost complete lack of physical dependence, further suggesting dissociation between physical dependence and drug abstinence-induced emotional dysfunction (data not shown). In a broader perspective, these findings nicely fit with epidemiological measures of similar levels of comorbidity between addiction and depression across all drugs of abuse, regardless of their potential for physical dependence (classically very low for nicotine or cocaine, for example).

In conclusion, our study unravels opioid receptors as essential players in the emotional syndrome of heroin abstinence. We show that, during prolonged heroin abstinence, DORs regulate hedonic homeostasis, while MOR signaling in serotonergic pathways and KORs together control social behaviors. Our findings further deepen our knowledge on the neurobiology of sociability and emphasize the opioid system as a crucial substrate of the social brain at the intersection of addiction and emotional regulation.

FUNDING AND DISCLOSURE

This work was supported by Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale (to P-EL), Fondation Fyssen (to P-EL), Fondation Bettencourt-Schueller (to P-EL), Canadian Institutes of Health Research (to P-EL), Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale, and the Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR-Abstinence). The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Andersen JM, Ripel A, Boix F, Normann PT, Morland J (2009). Increased locomotor activity induced by heroin in mice: pharmacokinetic demonstration of heroin acting as a prodrug for the mediator 6-monoacetylmorphine in vivo. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 331: 153–161.

Anraku T, Ikegaya Y, Matsuki N, Nishiyama N (2001). Withdrawal from chronic morphine administration causes prolonged enhancement of immobility in rat forced swimming test. Psychopharmacology 157: 217–220.

Aston-Jones G, Harris GC (2004). Review—Brain substrates for increased drug seeking during protracted withdrawal. Neuropharmacology 47 (Suppl 1): 167–179.

Bakken K, Landheim AS, Vaglum P (2007). Axis I and II disorders as long-term predictors of mental distress: a six-year prospective follow-up of substance-dependent patients. BMC Psychiatry 7: 29.

Berger AL, Williams AM, McGinnis MM, Walker BM (2013). Affective cue-induced escalation of alcohol self-administration and increased 22-kHz ultrasonic vocalizations during alcohol withdrawal: role of kappa-opioid receptors. Neuropsychopharmacology 38: 647–654.

Berton O, Hahn CG, Thase ME (2012). Are we getting closer to valid translational models for major depression? Science 338: 75–79.

Blatchford KE, Diamond K, Westbrook RF, McNally GP (2005). Increased vulnerability to stress following opiate exposures: behavioral and autonomic correlates. Behav Neurosci 119: 1034–1041.

Bruchas MR, Land BB, Chavkin C (2010). The dynorphin/kappa opioid system as a modulator of stress-induced and pro-addictive behaviors. Brain Res 1314: 44–55.

Challis C, Boulden J, Veerakumar A, Espallergues J, Vassoler FM, Pierce RC et al (2013). Raphe GABAergic neurons mediate the acquisition of avoidance after social defeat. J Neurosci 33: 13978–13988.

Chu Sin Chung P, Kieffer BL (2013). Delta opioid receptors in brain function and diseases. Pharmacol Ther 140: 112–120.

Darke S, Mills K, Teesson M, Ross J, Williamson A, Havard A (2009). Patterns of major depression and drug-related problems amongst heroin users across 36 months. Psychiatry Res 166: 7–14.

Del Boca C, Lutz PE, Le Merrer J, Koebel P, Kieffer BL (2012). Cholecystokinin knock-down in the basolateral amygdala has anxiolytic and antidepressant-like effects in mice. Neuroscience 218: 185–195.

File SE, Seth P (2003). A review of 25 years of the social interaction test. Eur J Pharmacol 463: 35–53.

Filliol D, Ghozland S, Chluba J, Martin M, Matthes HW, Simonin F et al (2000). Mice deficient for delta- and mu-opioid receptors exhibit opposing alterations of emotional responses. Nat Genet 25: 195–200.

Gerra G, Borella F, Zaimovic A, Moi G, Bussandri M, Bubici C et al (2004). Buprenorphine versus methadone for opioid dependence: predictor variables for treatment outcome. Drug Alcohol Depend 75: 37–45.

Goeldner C, Lutz PE, Darcq E, Halter T, Clesse D, Ouagazzal AM et al (2011). Impaired emotional-like behavior and serotonergic function during protracted abstinence from chronic morphine. Biol Psychiatry 69: 236–244.

Goeldner C, Reiss D, Kieffer BL, Ouagazzal AM (2010). Endogenous nociceptin/orphanin-FQ in the dorsal hippocampus facilitates despair-related behavior. Hippocampus 20: 911–916.

Grasing K, Ghosh S (1998). Selegiline prevents long-term changes in dopamine efflux and stress immobility during the second and third weeks of abstinence following opiate withdrawal. Neuropharmacology 37: 1007–1017.

Grella CE, Karno MP, Warda US, Niv N, Moore AA (2009). Gender and comorbidity among individuals with opioid use disorders in the NESARC study. Addict Behav 34: 498–504.

Gururajan A, Taylor DA, Malone DT (2010). Current pharmacological models of social withdrawal in rats: relevance to schizophrenia. Behav Pharmacol 21: 690–709.

Hack SP, Bagley EE, Chieng BC, Christie MJ (2005). Induction of delta-opioid receptor function in the midbrain after chronic morphine treatment. J Neurosci 25: 3192–3198.

Harris GC, Aston-Jones G (1993). Beta-adrenergic antagonists attenuate somatic and aversive signs of opiate withdrawal. Neuropsychopharmacology 9: 303–311.

Harris GC, Aston-Jones G (2001). Augmented accumbal serotonin levels decrease the preference for a morphine associated environment during withdrawal. Neuropsychopharmacology 24: 75–85.

Hodgson SR, Hofford RS, Wellman PJ, Eitan S (2009). Different affective response to opioid withdrawal in adolescent and adult mice. Life Sci 84: 52–60.

Hyman SE, Malenka RC, Nestler EJ (2006). Neural mechanisms of addiction: the role of reward-related learning and memory. Annu Rev Neurosci 29: 565–598.

Jia W, Liu R, Shi J, Wu B, Dang W, Du Y et al (2013). Differential regulation of MAPK phosphorylation in the dorsal hippocampus in response to prolonged morphine withdrawal-induced depressive-like symptoms in mice. PLoS One 8: e66111.

Kallupi M, Wee S, Edwards S, Whitfield TW Jr., Oleata CS, Luu G et al (2013). Kappa opioid receptor-mediated dysregulation of gamma-aminobutyric acidergic transmission in the central amygdala in cocaine addiction. Biol Psychiatry 74: 520–528.

Kest B, Palmese CA, Hopkins E, Adler M, Juni A, Mogil JS (2002). Naloxone-precipitated withdrawal jum** in 11 inbred mouse strains: evidence for common genetic mechanisms in acute and chronic morphine physical dependence. Neuroscience 115: 463–469.

Klein G, Juni A, Waxman AR, Arout CA, Inturrisi CE, Kest B (2008). A survey of acute and chronic heroin dependence in ten inbred mouse strains: evidence of genetic correlation with morphine dependence. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 90: 447–452.

Knoll AT, Carlezon WA Jr. (2010). Dynorphin, stress, and depression. Brain Res 1314: 56–73.

Koob GF, Volkow ND (2010). Neurocircuitry of addiction. Neuropsychopharmacology 35: 217–238.

Lutz PE, Kieffer BL (2013a). Opioid receptors: distinct roles in mood disorders. Trends Neurosci 36: 195–206.

Lutz PE, Pradhan AA, Goeldner C, Kieffer BL (2011). Sequential and opposing alterations of 5-HT(1A) receptor function during withdrawal from chronic morphine. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 21: 835–840.

Lutz PE, Reiss D, Ouagazzal AM, Kieffer BL (2013b). A history of chronic morphine exposure during adolescence increases despair-like behaviour and strain-dependently promotes sociability in abstinent adult mice. Behav Brain Res 243: 44–52.

Ma MX, Chen YM, He J, Zeng T, Wang JH (2007). Effects of morphine and its withdrawal on Y-maze spatial recognition memory in mice. Neuroscience 147: 1059–1065.

Mandillo S, Tucci V, Holter SM, Meziane H, Banchaabouchi MA, Kallnik M et al (2008). Reliability, robustness, and reproducibility in mouse behavioral phenoty**: a cross-laboratory study. Physiol Genomics 34: 243–255.

Meyer-Lindenberg A, Tost H (2012). Neural mechanisms of social risk for psychiatric disorders. Nat Neurosci 15: 663–668.

Nunes EV, Sullivan MA, Levin FR (2004). Treatment of depression in patients with opiate dependence. Biol Psychiatry 56: 793–802.

Ornstein TJ, Iddon JL, Baldacchino AM, Sahakian BJ, London M, Everitt BJ et al (2000). Profiles of cognitive dysfunction in chronic amphetamine and heroin abusers. Neuropsychopharmacology 23: 113–126.

Pickens CL, Airavaara M, Theberge F, Fanous S, Hope BT, Shaham Y (2011). Neurobiology of the incubation of drug craving. Trends Neurosci 34: 411–420.

Pothion S, Bizot JC, Trovero F, Belzung C (2004). Strain differences in sucrose preference and in the consequences of unpredictable chronic mild stress. Behav Brain Res 155: 135–146.

Ragozzino ME, Gold PE (1995). Glucose injections into the medial septum reverse the effects of intraseptal morphine infusions on hippocampal acetylcholine output and memory. Neuroscience 68: 981–988.

Rapeli P, Kivisaari R, Autti T, Kahkonen S, Puuskari V, Jokela O et al (2006). Cognitive function during early abstinence from opioid dependence: a comparison to age, gender, and verbal intelligence matched controls. BMC Psychiatry 6: 9.

Sakoori K, Murphy NP (2005). Maintenance of conditioned place preferences and aversion in C57BL6 mice: effects of repeated and drug state testing. Behav Brain Res 160: 34–43.

Schlosburg JE, Whitfield TW Jr., Park PE, Crawford EF, George O, Vendruscolo LF et al (2013). Long-term antagonism of kappa opioid receptors prevents escalation of and increased motivation for heroin intake. J Neurosci 33: 19384–19392.

Simonin F, Schmitt M, Laulin JP, Laboureyras E, Jhamandas JH, MacTavish D et al (2006). RF9, a potent and selective neuropeptide FF receptor antagonist, prevents opioid-induced tolerance associated with hyperalgesia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 466–471.

Smith JS, Schindler AG, Martinelli E, Gustin RM, Bruchas MR, Chavkin C (2012). Stress-induced activation of the dynorphin/kappa-opioid receptor system in the amygdala potentiates nicotine conditioned place preference. J Neurosci 32: 1488–1495.

Solecki W, Ziolkowska B, Krowka T, Gieryk A, Filip M, Przewlocki R (2009). Alterations of prodynorphin gene expression in the rat mesocorticolimbic system during heroin self-administration. Brain Res 1255: 113–121.

Tao R, Auerbach SB (2002). GABAergic and glutamatergic afferents in the dorsal raphe nucleus mediate morphine-induced increases in serotonin efflux in the rat central nervous system. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 303: 704–710.

Tao R, Auerbach SB (2005). mu-Opioids disinhibit and kappa-opioids inhibit serotonin efflux in the dorsal raphe nucleus. Brain Res 1049: 70–79.

Trezza V, Baarendse PJ, Vanderschuren LJ (2010). The pleasures of play: pharmacological insights into social reward mechanisms. Trends Pharmacol Sci 31: 463–469.

Ukai M, Watanabe Y, Kameyama T (2000). Effects of endomorphins-1 and -2, endogenous mu-opioid receptor agonists, on spontaneous alternation performance in mice. Eur J Pharmacol 395: 211–215.

Wall PM, Blanchard RJ, Yang M, Blanchard DC (2003). Infralimbic D2 receptor influences on anxiety-like behavior and active memory/attention in CD-1 mice. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 27: 395–410.

Weibel R, Reiss D, Karchewski L, Gardon O, Matifas A, Filliol D et al (2013). Mu opioid receptors on primary afferent nav1.8 neurons contribute to opiate-induced analgesia: insight from conditional knockout mice. PLoS One 8: e74706.

Wikler A, Pescor FT (1970). Persistence of ‘relapse-tendencies’ of rats previously made physically dependent on morphine. Psychopharmacologia 16: 375–384.

Zhang D, Zhou X, Wang X, **ang X, Chen H, Hao W (2007). Morphine withdrawal decreases responding reinforced by sucrose self-administration in progressive ratio. Addict Biol 12: 152–157.

Zhao ZQ, Gao YJ, Sun YG, Zhao CS, Gereau RWt, Chen ZF (2007). Central serotonergic neurons are differentially required for opioid analgesia but not for morphine tolerance or morphine reward. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 14519–14524.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Mouse Clinical Institute (Illkirch, France), in particular Hamid Meziane. We also thank Claire Gaveriaux-Ruff for constant scientific exchanges and for assistance with ethical and administrative authorizations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the Neuropsychopharmacology website

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lutz, PE., Ayranci, G., Chu-Sin-Chung, P. et al. Distinct Mu, Delta, and Kappa Opioid Receptor Mechanisms Underlie Low Sociability and Depressive-Like Behaviors During Heroin Abstinence. Neuropsychopharmacol 39, 2694–2705 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2014.126

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2014.126

- Springer Nature Switzerland AG

This article is cited by

-

Upregulation of dynorphin/kappa opioid receptor system in the dorsal hippocampus contributes to morphine withdrawal-induced place aversion

Acta Pharmacologica Sinica (2023)

-

Inhibition of dorsal raphe GABAergic neurons blocks hyperalgesia during heroin withdrawal

Neuropsychopharmacology (2023)

-

Facilitating mGluR4 activity reverses the long-term deleterious consequences of chronic morphine exposure in male mice

Neuropsychopharmacology (2021)

-

Mu opioid receptors in the medial habenula contribute to naloxone aversion

Neuropsychopharmacology (2020)

-

Very low dose naltrexone in opioid detoxification: a double-blind, randomized clinical trial of efficacy and safety

Toxicological Research (2020)