Abstract

The present study empirically tests the relationship between crop diversification and farm income. The study area is India, the fifth largest economy of the world, and the units of study are its households which dominates India’s labor force. The propensity score matching technique is applied on the two waves of nationally representative data on agricultural households pertaining to agricultural year 2012–13 & 2018–19 to test the relationship between crop diversification and farm income. We find a strong and positive impact of crop diversification on farm income as farm income increases by around 13 per cent if non-diversified households opt for crop diversification. Furthermore, important factors such as literacy, access to market, access to irrigation, agricultural training, farming experience, and household size positively affects crop diversification at the household level. However, recent decline in the extent of diversification in India is a cause for concern. Promotion of cultivation of HVCs by giving them such institutional supports as initial capital required for switch to HVCs and other steps that insulates them from higher risks is the need of the hour in Indian agriculture.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Agriculture in India has been a low-income generating sector for its dependent workforce since a very long time, in general and vis-a-vis industrial and services sectors, in particular. In India, a worker working in primary sector earned a daily wage rate of ₹ 192, while a daily wages of a worker in its secondary and tertiary were at ₹ 357 and ₹ 424 in 2011–12 [1]. The situation of casual workers in agricultural sector is even more concerning as their daily wages are much lower than these figures which pertains to regular workers. Prevailing lower daily wage in primary sector has serious welfare implications given that contribution of wages in total income of agricultural households has increased, between 2002–03 and 2018–19, in as many as twelve states of India and share of cultivation has declined in as many as sixteen states [2]). Furthermore, precariously low level of farm income on the one hand and large variations of the same across states is a reality in India [3,4,5,6]. To put the issue of low farm income in perspective, the average monthly income of an agricultural household in India, from all major sources such as cultivation, livestock, wages and salaries, and non-farm enterprises, was recorded at ₹ 6426 and ₹ 10,218 in 2012–13 and 2018–19, respectively [7, 8]. Furthermore, falling share of cultivation in the total income of agricultural household [9] has become one of the most serious issues given that around 55 per cent of India’s workforce still depend on agriculture and around 85 per cent of Indian farmers are marginal and small who fall back on to cultivation for their food, income and livelihood security. The Government of India in 2016, realizing the importance of this problem, changed the main objective its agricultural policy from maximizing agricultural production and productivity to doubling farmers’ income. In this scenario, crop diversification has been argued as a win–win strategy particularly for marginal and small farmers, for it reduces the risks and uncertainties attached with cultivation [10, 11], generates higher employment [12, 13] and positively affects farm income [12,13,14,15,16,17,18] which further results in reduction in poverty [3, 19,20,21,22,23]. Given all its benefits, promotion of crop diversification is all but expected provided that the most fundamental contribution of diversification that is raising of farm income stands scientific empirical scrutiny. The empirical scrutiny of the relationship between crop diversification and farm income is all the more important. We have now with us the recently published large scale survey data on agricultural households in India by the national sample office, Government of India. And earlier established positive relationship between crop diversification and farm income on the basis old data set needs to looked into given the availability of new data set. And, to our knowledge, this relationship has not been studied yet using the recent unit level data on agricultural households in India and our study intend to fill this important gap. Therefore, the present study employing quasi-experimental approach empirically tests the relationship between crop diversification and farm income in India using a reliable and most recent nationally representative data set.

The study is organized and presented in four sections including the introduction. The following section discusses the data sources in detail and the advantages of the quasi-experimental method used in our study. Discussion of results is done in the third section, which is followed by the conclusion of the study.

2 Material and methods

2.1 Data and variables

Our study uses two waves (70th and 77th round) of nationally representative data on agricultural households provided by the National Sample Survey (NSS) office, Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, Government of India (GoI). The NSS 70th round survey on the title ‘Situation Assessment Survey of Agricultural Households in India’, was conducted during January–December, 2013. And the NSS 77th round survey on the title ‘Land and Livestock Holdings of Households and Situation Assessment of Agricultural Households’ was conducted during January–December, 2019. While the former round surveyed a nationally represented sample of 34,907 agricultural households, 56,894 agricultural households were surveyed in later round. In both the rounds each household was surveyed in both the main agricultural seasons, namely Kharif (July–December) and Rabi (January–June), of India. We have borrowed the definition of agricultural household in India from NSS which defined an agricultural household as (i) ‘agricultural production unit’ which produced field crops, horticultural crops, livestock and the products of any of the other specified agricultural activities with or without possessing and operating any land; (ii) the household must receive a value of produce worth more than Rs. 3000/– from agricultural activities; and (iii) the household must have at least one self-employed member in agriculture during the last 365 days from the date of survey. One aspect of this definition was changed in the 77th round and that is the value of the produce from agricultural activities was increased from Rs. 3000/– to Rs. 4000/– to account for the inflation. Other definitions of the concepts and variables used in the two surveys are same and therefore the data from both the rounds are broadly comparable.

We define diversified households as those who cultivate at least one of the crops from the crop varieties such as fruits, vegetables, flowers, plantations, spices, condiments, and medicinal plants. These crops are also otherwise known as high value crops (HVCs). And the non-diversified households are those who did not cultivate any of the HVCs. This definition of crop diversification was also adopted by [3]. Farm income is the total value of the produce minus total input expenses for crop production and it constitutes a part of total income of an agricultural household; other sources of annual income of agricultural households such as income from livestock, income from wages, income from remittances, income from rent received from leased-out land, and income from non-farm enterprises are excluded from our definition of farm income for crop diversification is unlikely affect income from sources other than cultivation. A brief description of the variables used and their descriptive statistics are given in Table 1.

2.2 Propensity score method (PSM)

The study uses PSM to determine the implications of crop diversification on farm income. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are now being increasingly used for computing the effects of treatments or interventions using experimental data. However, RCTs cannot be used on our data set as it is generated from surveys. For observational and survey data, PSM mimics RCTs and gives exact effect of treatment on outcome variable. The propensity score, calculated by PSM, has the distinct advantage of providing the exact effect on farm income of adopting diversification vis-à-vis non-adopting diversification. The propensity score is just a number but it is based on the distribution of such measured baseline covariates which is similar between treated and untreated subjects [24]. We have used nearest neighbor-based approach for pairing of households from treated and controlled group which selects for comparison the household from control group whose propensity score is most similar to the propensity score of the household from the treated group. The PSM has a two-step procedure. In the first step, before estimating the effect of diversification on farm income, we account for systematic differences in baseline characteristics of diversified treated group and control group by using a logit regression model. Treated group and control group are the diversified households and non-diversified households, respectively.

The logit model is specified as \({P}_{i}=P\left({Y}_{i}=1\right)=F\left({Z}_{i}\right)=\frac{1}{1+{e}^{{-z}_{i}}}\)

Here, \({P}_{i}\) is the probability of \({Y}_{i}=1\), where Y is status of diversification and ‘i’ represent household. If \({Y}_{i}=1\), then ith household is diversified and if \({Y}_{i}=0\), then ith household is non-diversified. \(F\left({Z}_{i}\right)\) is the cumulative distribution function of the cumulative logistic function.

The above model is calculated using maximum likelihood method and then marginal effects (\(\frac{{dP}_{i}}{{dX}_{i}}\)) of the explanatory variables are computed and interpreted as the change in \({P}_{i}\) (or probability of ith household opting for diversification) as a result of a one-point change in \({X}_{i}\).

In the second step, calculation of average treatment effect for the treated (ATT), average treatment effect for the untreated (ATU), and average treatment effect (ATE) is done. This gives the exact effect of diversification on farm income. These are calculated both in nominal and real terms. Real farm income is calculated using consumer price index for rural labourers (CPIRL) published by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI). The CPIRL in June 2013 and June 2019 was at ₹ 108.9 and ₹ 143.6, respectively. It is important to underline that exchange rate of Indian rupee vis-à-vis US dollar, calendar year average was 58.5978 and 70.4203 in 2013 and 2019, respectively. It may help ensure a broader international perspective of the figures in Indian rupees presented in our paper.

Let ‘\(Y\)’ be farm income and ‘\(i\)’ be \(i\) th agricultural household, then the potential values for outcome variable \(Yi(0)\) or \(Yi(1)\) are the farm income (or outcome values) for the controlled household (non-diversified household) and treated household (diversified household), respectively. However, if we take another indicator variable ‘\(G\)’ representing the treatment received, to be precise \(G=0\) for controlled treatment and \(G=1\) for active treatment, then there will be only one outcome, that is,

Now for each household, effect of treatment is measured by \(Yi(1)-Yi(0).\)

The ATE is \(E[Yi(1)-Yi(0)]\). It measures the average of the difference in farm income between the two groups.

ATT, which is \(E\left[Yi\left(1\right)-Yi\left(0\right)\right|G=1]\), measures the difference between the farm income of diversified agricultural households and the expected farm income they would have achieved if they had not gone for diversification.

ATU is defined as \(E\left[Yi\left(1\right)-Yi\left(0\right)\right|G=0]\). It measures the difference between the expected farm income that non-diversified households would have achieved if they had diversified and the actual farm income of the non-diversified households.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Key attributes of diversified and non-diversified agricultural households in India

Table 2 compares some important household level attributes of diversified and non-diversified agricultural households in India. It can be observed from the table that around 35 per cent of an estimate of 90.2 million agricultural households in 2012–13 and 30 per cent of an estimate of 93.09 million total agricultural households are diversified in 2018–19; leaving a majority of agricultural households in the non-diversified category; and around 5 percentage point reduction in the extent of diversified households during the time points. This result is similar to the findings of [9] in which he found declining extent of crop diversification in sixteen major states. He also found the acreage under non foodgrain crops including fruits and vegetables in most of the states in India to have declined by varying degree. Another study by [25] using a district level time series data ranging from 1947 and 2014 found a strong negative association between diversity and intensification of cultivation. This ultimately resulted in a strong decline in crop diversity in India over a 60-year period in certain regions, particularly in the rice and wheat-producing districts of the Indo-Gangetic Plains. However, there happened an increase in diversity in western and southern India due to expansion of oilseeds and horticultural crops that replaced millet and sorghum. Contrasting scenarios in Indo-Gangetic Plains and western and southern India eventually canceled each other out the trend of crop diversity at national level.

Distribution of diversified and non-diversified households in terms of caste group reveals that while SCs have comparatively the lowest share, it is the OBCs who have the highest share, and percentage of ST households went up from 26.48 per cent in 2012–13 to 28.32 per cent in 2018–19 in the category of diversified households. [26] in their empirical study on rural India found that initial proximity gains (gains in terms of income differentials) of SCs and OBCs outweighs negative oppression effects (which is that upper-caste-dominated villages are located in more productive areas); however, after controlling for agroecology, proximity effects (when SCs and OBCs are villages dominated by upper caste) and oppression effects (in terms lower land possession and higher population) cancel each other out. The fact that SCs have lack of access to productive lands, are socially and economically weaker than upper castes, and their higher extent of poverty may explain why SCs are not known for crop diversification towards HVCs in India for among other things crop diversification needs productive lands, higher initial capital and an economically better off status to cope with its higher risks. In yet another study [27], socially disadvantaged households are found to have lower access to land and other resources such as information, technology, inputs, markets, and support institutions. And, among all the social groups, net returns of ST farmers are significantly higher, for their practice of cultivation of HVCs which generates higher income. STs comparatively allocate higher percentage of their total cultivated area for HVC cultivation. Therefore, our finding of higher share of ST households in diversified category has literature support.

A comparative observation of select key attributes of diversifiers and non-diversifiers allows us to state that diversified agricultural households are more literate, more experienced, their household size is bigger, and they have higher access to technical advice, market, agricultural training, and institutional credit. But diversified households have lower extent of MSP awareness and lower access to irrigation. As is evident from Table 2, differences in the key attributes for both the groups are statistically significant. Evidence of higher level of education promoting crop diversification was also found by [28,29,30].

HVCs are labour intensive and because a bigger family size is associated with higher availability of family labour, a comparatively larger family is associated with diversified households. Irrigation facilities and successful access to MSP are two of the prerequisites for high yield variety cereal cultivation, for it is highly water intensive and MSP assures guaranteed returns (particularly for medium and large farmers as is observed from Punjab and Haryana agriculture which continue experience a low extent of crop diversification). Therefore, it is not surprising to find that diversified farmers have comparatively both low access to irrigation and lower MSP awareness. However, comparatively low access to irrigation may not imply its negative relationship with crop diversification as will be evident in the next section (Table 3) in which we discuss the results of logit regression on the covariates of diversification.

3.2 Results from PSM

3.2.1 Covariates of diversification

First step of PSM approach through the results of logistic regression further establishes the results, with exception of access to irrigation, found in the previous section. A glance at Table 3 allows us to make the following statements. First, both farming experience and household size have positive and significant relationship with diversification in both the time points; and higher farming experience and larger family size increases the probability of diversifying towards HVCs. Age of the farmer is a proxy for farmer’s experience. Decision regarding diversification which is a relatively risky option is usually taken by an experienced farmer. Similarly, it is well known that high value crops are labor intensive. And larger family size offers higher family labor and it helps in the process of crop diversification. Second, in reference to general category household, coefficient of ST households is higher in 2012–13 and 2018–19, but statistically significant in 2018–19, coefficients of SC and OBC households are lower and significant in both time points. It implies that probability of diversification increases with ST (only in 2018–19) and decreases with SC and OBC. Third, Literacy is increasing the probability of diversification by 13 per cent and around 10 per cent in 2012–13 and 2018–19, respectively. A literate farmer is relatively better placed to diversify towards high value crops as its practices involve higher technology, involvement with extension agents for technical advice and advanced post-harvest value chains. Fourth, access to market is another important variable which is positively and significantly affecting the probability of diversification towards HVCs. Access to market is a key thing for better realization prices for produce. And high value crops are usually perishable in nature and may lead to huge losses in the absence of proper market. Therefore, provision of better markets is a pre-requisite for shifting towards HVcs. Fifth, coefficient of access to technical advice and institutional credit is insignificant in 2018–19, but the same for agricultural training becomes significant and increase the probability of diversification by almost 19 per cent in 2018–19. Sixth, coefficient for access to irrigation is positive and significant implying its key role in the process of crop diversification. Availability of adequate water through better irrigation facilities promotes crop diversification as it removes that uncertainty regarding productivity due to lack of water at appropriate times. Lastly, although coefficients for MSP are negative and significant in both the time points, whether or not it is a hindrance in the process of diversification needs further empirical analysis precisely because its marginal effect (− 0.012 to be precise) is very low.

3.2.2 Diversification and farm income

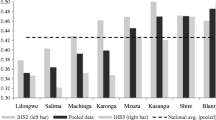

Results of 2nd and final step of PSM method is given in Table 4. It is revealed from the table that diversified agricultural households, whose actual income from cultivation stood at ₹ 46,515 in 2012–13 and ₹ 54,934 in 2018–19, would have earned a considerably lower farm income of ₹ 44,191 and ₹ 51,293 in 2012–13 and 2018–19, respectively if they had not opted for crop diversification. To be precise diversified households would have earned a significantly lower farm income of ₹ 2324 and ₹ 3641 in nominal terms and ₹ 2134 and ₹ 2535 in real terms, in 2012–13 and 2018–19, respectively had they not opted for crop diversification. Similarly, farm income of non-diversified households would have increased to ₹ 2678 and ₹ 6116 in nominal terms and ₹ 2459 and ₹ 4259 in real terms in 2012–13 and 2018–19, respectively had they gone for crop diversification. In percentage terms, farm income of non-diversified farmers would have increased by about 13 per cent in 2018–19 if they had gone for crop diversification. To sum up, the difference in the farm income of diversified and non-diversified agricultural households, as is evident from positive ATE in both the time points and in both nominal and real terms, proves that crop diversification shoots up farm income in India. The result is all the more significant in the sense that it is coming out of the two waves of nationally representative NSS data on agricultural households covering the time period from 2012–13 to 2018–19.

4 Conclusion

Our study, inter alia, tests the relationship between crop diversification and farm income in India by analyzing two waves of nationally representative data on agricultural households through a popular quasi-experimental method named PSM method. We find a strong and positive impact of crop diversification on farm income so much so that farm income increases by around 13 per cent if non-diversified households opt for crop diversification. This calls for resurgent policy measures for promotion of crop diversification in India. It may in the long-run help in doubling farmers’ income which is the key objective of Indian agricultural policy. However, recent decline in the extent of crop diversification is a cause of concern which should be checked through targeted policy focus. Our study finds important factors such as literacy, access to market, access to irrigation, agricultural training, farming experience, and household size to positively affect crop diversification at the household level. Therefore, policy makers would do well to take steps so that Indian farmers get higher level of education, improved access to market, better irrigation facilities, and timely agricultural training. Further, advertising the successful practice of crop diversification of the STs can help other disadvantaged section SCs to take up crop diversification. This is particularly important for SCs as their participation in crop diversification is meagre. There is a chance to promote cultivation of HVCs among SCs by giving them such institutional supports which give them initial capital required for switch to HVCs and other steps that insulates them from higher risks.

Data availability

The secondary data used in the manuscript pertains to 70th and 77th round survey of National Sample Survey Office of Government of India and it is available in the download section of www.mospi.gov.in. The corresponding author can share the data set upon request.

References

ILO. India Wage Report: Wage policies for decent work and inclusive growth, International Labour Organization, 2018. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---asia/---ro-bangkok/---sro-new_delhi/documents/publication/wcms_638305.pdf

Narayanamoorthy A, Nuthalapati CSR, Sujitha KS. Dynamics of farmers income growth: regional and sectoral winners and losers from three-time SAS data. Indian J Agric Econ. 2022;77(3):368–84.

Birthal PS, Roy D, Negi DS. Agricultural diversification and poverty in India. International Food Policy Research Institute, 2015.

Chandrasekhar S, Mehrotra N. Doubling farmers’ incomes by 2022. Econ Pol Wkly. 2016;51(18):10–3.

Narayanamoorthy A. Farm income in India: h. Indian J Agric Econ. 2017;72(1):49–75.

Basantaray AK, Nancharaiah G. Relationship between Crop Diversification and Farm Income in Odisha: An Empirical Analysis. Agricultural Economics Research Review. vol. 30, no. Conference, pp. 45–58.

NSSO. Key indicators of situations of agricultural households in India. Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, Government of India, New Delhi, 70th Round, 2014.

NSSO. Situation assessment of agricultural households and land and holdings of households in rural India 2019, Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, Government of India, New Delhi, Situation Assessment Survey 77th Round, 2021.

Sharma HR. Patterns, sources and determinants of agricultural growth in India. Indian J Agric Econ. 2023;78(1):26–70.

Quiroz JA, Valdés A. Agricultural diversification and policy reform. Food Policy. 1995;20(3):245–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/0306-9192(95)00016-8.

Kumar A, Sharma SK, Vashist GD. Profitability, risk and diversification in mountain agriculture: some policy issues for slow growth crops. Indian J Agric Econ. 2002;57(3):356–65. https://doi.org/10.22004/ag.econ.297892.

Ali M, Abedullah M. Economic and nutritional benefits from enhanced vegetable production and consumption in develo** countries. J Crop Prod. 2002;6(1–2):145–76.

Benziger V. Small fields, big money: two successful program in hel** small farmers make the transition high value added crops. World Dev. 1996;24(11):1681–93.

Sharma HR. Agricultural development and crop diversification in Himachal Pradesh: understanding the patterns, processes, determinants and lessons. Indian J Agric Econ. 2005;60(1):71–93.

Sharma HR. Agricultural development and crop diversification in Himachal Pradesh: understanding the patterns, processes, determinants and lessons. Indian J Agric Econ. 2011;60(1):97–114.

Makate C, Wang R, Makate M, Mango N. Crop Diversification and livelihoods of smallholder farmers in zimbabwe: adaptive management for environmental change. S**er Plus. 2016;5(1):1135.

Perz S. Are agriculture production and forest conservation compatible? Agricultural diversity, agricultural incomes, and primary forest cover among small farm colonists in the amazon. World Dev. 2004;32(6):957–77.

Huang J, Rozelle S. Moving off the farm intensifying agricultural production in shandong: a case study of rural labour market linkages in China. Agric Econ. 2009;40(2):203–18.

Weinberger K, Thomas AL. Diversification into horticulture and poverty reduction: a research agenda. World Dev. 2007;35(8):1464–80.

Goletti F. Agricultural diversification and rural industrialisation as a strategy for rural income growth and poverty reduction in indonesia and myanmar. Washington DC, 1999.

Waha K, et al. Agricultural diversification as an important strategy for achieving food security in Africa. Global Change Bio. 2018;24(8):3390–400.

Zeba P, Shazia S. Agriculture diversification and food security concerns in India. IOSR J Agric Veterinary Sci. 2016;9(11):56–63.

Thapa G, Kumar A, Roy D, Joshi PK. Impact of crop diversification on rural poverty in Nepal. Canadian J Agric Econ. 2018;66(26):379–413.

Austin PC. An introduction to propensity score methods for reducing the effects of confounding in observational studies. Multivar Behav Res. 2011;46(3):399–424.

Smith JC, Ghosh A, Hijmans RJ. Agricultural intensification was associated with crop diversification in India (1947–2014). PLoS ONE. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0225555.

Iversen V, Kalwij A, Verschoor A, Dubey A. Caste dominance and economic performance in rural India. Econ Dev Cult Change. 2014;62(3):423–57. https://doi.org/10.1086/675388.

Khan MR, Haque M, Zeeshan I, Khatoon N, Kaushik I, Shree K. Caste, land ownership and agricultural productivity in India: evidence from a large-scale survey of farm households. Dev Pract. 2021;31(4):421–31.

Idrisa YI, Gwary MM, Shehu H. Analysis of food security status among farming households in JERE local government of Bonro state, Nigeria. J Tropic Agric Food Environ Extens. 2008;7(3):199–205.

Makombe T, Lewin P, Fisher M. The determinants of food insecurity in rural Malawi : implications for agricultural policy. International Food Policy Research Institute. 2010.

Douyon A, et al. Impact of crop diversification on household food and nutrition security in Southern and Central Mali. Front Sustain Food Syst. 2022;5(January):1–11.

Funding

The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript. The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Research conceptualization, framing of objectives, data analysis, and discussion of results are done by the first author. The second author extracted, tabulated, and presented the data for analysis. The third author double checked the results and fine tuned the flow of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Additional file 1:

Appendix A. Fulfilment of the condition of common support. Appendix B: Balance in covariates before and after matching. Appendix C. Percentage Bias Reduction after Balancing of the Covariates.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Basantaray, A.K., Acharya, S. & Patra, T. Crop diversification and income of agricultural households in India: an empirical analysis. Discov Agric 2, 8 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44279-024-00019-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44279-024-00019-0