Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic induced governments all over the world to momentarily accumulate higher levels of public debt in order to invest in deficit spending and social protection programs to tackle the anticipated economic slump. The Nigerian government has borrowed heavily from domestic and foreign sources in order to resolve the growing budget deficits and return the economy to a sustainable growth trajectory. Previous studies frequently made the incorrect assumption that the relationship between public debt and growth is linear and symmetric, leading to empirical results that is frequently disputed and imprecise. This study’s main objective is to examine the asymmetric impact of public debt on economic growth in Nigeria from 1980 to 2020 using the Nonlinear Autoregressive Distributed Lag method. Empirical evidence indicated that external debt have a significant positive and symmetric impact on economic growth in the long and short run, while debt service payment supporting the debt overhang hypothesis activated a symmetric effect that stifle growth. Domestic debt retarded growth asymmetrically in the short term and linearly over the long term. Foreign reserve holding, on the other hand, had an asymmetric long-run influence and a symmetric short-run impact on growth motivation. To mitigate the negative effects of unsustainable public debt, the study advocated for fiscal reforms that effectively reduce deficit financing to keep the level of government debt low and be able to respond robustly to an economic shock, improve domestic revenue generation and infrastructure spending, and strengthen governance practices and institutions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals, among other things, necessitates substantial infrastructure investments, human capital, and climate change resilience. However, develo** countries have few options for raising public funds or attracting private investment. Thus, debt is one of the levers used by these countries to meet growth funding requirements, but at unsustainable levels that jeopardize economic growth. Government borrow from domestic or external sources to bridge both short and long-term resource gaps and stimulate growth when revenue falls short of government expenditure. Thus, public debt is a crucial tool the government might use to successfully finance capital formation, sustain public expenditures, and spur economic growth, especially in situations where it is challenging to increase taxes and reduce public spending. In the event of an unanticipated and transient catastrophe, public debt can also be used as a safety net to reduce the need to rapidly raise taxes to finance higher spending (Bongumusa et al. 2022). The issue of growth sustainability is central to international concerns, particularly for develo** countries whose economies rely on natural resources and the environment. Many of Africa’s low-income countries have experienced rapidly rising levels of government debt over the years. High levels of government debt have a severe and long-term impact on the economic prospects of many emerging and develo** economies, owing to manifestations such as debt overhang and debt trap. Furthermore, debt repayment is costly because it depletes already scarce financial resources. As a result, the emphasis shifts from growth opportunities to debt repayment (Komlan and Essosinam 2022).

Traditionally, African economies have been defined by fiscal governments that have amassed large amounts of debt from external and domestic sources. This reliance on debt, as demonstrated by African economies, stems primarily from governments’ failure to fund much-needed expenditure programs solely through the collection of tax revenues. As a result, African governments have been forced to borrow primarily to stimulate the economy by channeling funds from foreign investors into the domestic economy. However, the overall cost of debt to African governments has long been a source of concern for academics and policymakers alike, with the central question being whether public debt is beneficial or detrimental to economic growth. While it is acknowledged that public borrowing is unavoidable in African economies for the financing of fiscal activities, it is worth noting that public debt is a double-edged sword that can be beneficial if, in the long run, the investment returns fully recoup the debt or, at the very least, the resulting welfare benefits exceed the cost. If not, the outcome is a debt trap that is challenging to escape (Martin and Aleš 2020). A nation’s capacity to expand its economy is significantly hampered by an ever-growing debt burden. This is due to the fact that debt servicing is more expensive and may become unaffordable for the debtor country, limiting its ability to achieve its fiscal and monetary goals. Government borrowing can also discourage private investment, lowering future output and profits and jeopardizing the standard of living. High public debt makes procyclical fiscal policy more difficult to implement, which can increase instability and weaken growth (Àkos and Istvàn 2019).

There is currently no agreement in the theoretical or empirical literature on the effects of government debt on the economy. While some economic theories alluded to the fact that reasonable public debts (both domestic and external) is necessary especially for low-income countries to raise living standards and economic growth, an increasing debt burden inflicts a perilous logjam on the pathway to economic growth of nations (Saungweme and Odhiambo 2019). When a government cannot raise enough money to pay off its debts, either defaulting on them or inflating them away, a debt crisis results. The subsequent arduous phases of financial stabilization and economic restructuring result in enormous social and economic consequences for both measures (Malachy et al. 2022). Traditional theories, such as the debt Laffer curve, contend that reasonable levels of government debt can stimulate economic growth. Government debts begin to impede economic growth only when they exceed a certain, reasonable threshold. Government debt used to acquire capital stock or finance expenditure, according to the endogenous growth model, could have a detrimental effect if not managed efficiently. A substantial body of extant theoretical and empirical literature supports the view that unsustainable public debt diminishes a country’s competitiveness and makes its financial markets more vulnerable to international shocks (Mhlaba and Phiri 2019).

Recent evidences suggest that resource-rich countries such as Nigeria are more likely to be overwhelmed by over borrowing and the associated debt unsustainability resulting in repayment difficulties as well as a drag on growth and other development goals (Ndoricimpa 2020). Despite getting debt relief in 2005, Nigeria’s government debt has been continuously rising. The Federal government’s borrowings (local and foreign debt) increased by around 658% from N3.55 trillion to N26.91 trillion between 1999 and March 2021, indicating that successive governments have continued to borrow enormously (Debt Management Office 2022). Nigeria’s domestic debt expanded significantly between 1981 and 1990, rising from N11.19 billion to N84.09 billion, then to N898.25 billion in 2000, N4551.82 billion in 2010, N7904.02 billion in 2014, and N11,058.20 billion in 2016. The external debt profile exhibited a nearly same pattern, rising dramatically from N2.33 billion in 1981 to N298.61 billion in 1990, then again to N3097.38 billion in 2000, before reaching a record high of N4890.27 billion in 2004.

Nigeria’s overall external debt decreased from $30 to $3.4 billion in 2006 thanks to the debt relief measures obtained from the Paris Club of creditors in 2005. The negotiation for debt relief was largely driven by the desire to free up funds for investment and more rapid economic growth in the nation. As of June 30, 2022, Nigeria’s entire public debt stock—which includes the federal government, the 36 state governments, and the federal capital territory (FCT)—rose to N42.84 trillion ($103.31 billion USD). This is made up of N16.61 trillion ($40.05 billion USD) in external debt. Concessional and semi-concessional loans from bilateral and multilateral lenders, including the World Bank, the IMF, Afrexim, and African Development Bank, made up 58% of the country’s external debt. Domestic debt increased to N25.23 trillion ($63.24 billion USD) as a result of fresh borrowings by the federal government, state governments and the FCT to cover mounting budget deficits (DMO 2022). When compared to 2005, right before Nigeria benefited from the significant debt relief, the whole debt structure and its total stock had quadrupled. To have squandered the debt reduction in just seventeen years while having no discernible economic gain to show for it is a tragedy beyond comprehension (Omotor 2019).

The monetization of fiscal deficits and CBN lending to government through Ways and Means advances has risen to N19.9 trillion in 2022, exceeding the threshold set by CBN laws (CBN 2022). These Ways and Means advances are temporary overdraft facilities provided to the Federal Government of Nigeria (FGN) to help with financial difficulties caused by a cash flow mismatch by bridging the gap between expenditure and revenue receipts. This level of borrowing from the Central Bank of Nigeria to finance fiscal deficit is clearly unsustainable, fueling inflation and endangering growth (Malachy et al. 2022). According to Komlan and Essosinam (2022), nations that adopt unsustainable fiscal policies have an ever-increasing debt-to-GDP ratio that violates their budgetary restraint. High debt levels result in high debt servicing, which lowers the amount of money available for investment in infrastructure and other economic sectors. The nation debt profile is likely to continue to increase in the face of expanding fiscal deficit and low revenue generating capacity. This is concerning because the country’s debt profile is becoming more and more dominated by commercial debt (Abdulkarim and Mohd. 2021a).

Despite having experienced recurring debt glitches since the 1980s and the recent trepidations about a looming debt crisis in Nigeria, empirical research on the nonlinear influence of government debt on economic growth is scarce. The current study tried to answer one of the important dilemmas African economies in general and Nigeria in particular has with respect to managing macroeconomic imbalances. It addresses the asymmetric impact of domestic and external debt on real GDP growth, an issue of pressing concern for many low and middle- income countries, including Nigeria, in the wake of increased government stimulus during the COVID-19 pandemic. In the case of Nigeria, concerns over the rising debt stock predates the fiscal crisis precipitated by the COVID-19 pandemic as debt service to revenue ratios have been growing over time. This has resulted in a diminishing share of revenues left over for investment once debts are serviced and statutory obligations by the federal and sub- national governments are fulfilled (Festus et al. 2022). This makes the selection of Nigeria for this study very apt.

Several empirical research on the relationship between public debt and economic growth have yielded varied results. Many studies have claimed that the growth effect of debt is mostly dependent on debt levels, and that the debt–growth relationship is defined by the presence of a debt–growth threshold at which debt has a negative influence on growth (Pattillo et al. 2011; Rogoff and Reinhart 2010; Checherita-Westphal and Rother 2012; Woo Kumar 2015). Their findings revealed that as debt levels rose, so did real interest rates, reducing investment and economic growth. Consequently, countries with high levels of debt grow at a slower rate than those with lower levels. While these studies are concerning for countries with higher levels of debt, their findings are cross-country in scope and served as a foundation for examining the asymmetric effect of public debt on economic growth in Nigeria.

In addition, majority of extant empirical studies (see Abdulkarim and Mohd, 2021a; Eze et al. 2019; Chinanuife et al. 2018; Miftahu and Tunku 2017) on the effect of public debt on growth or on different sectors of the economy generally assume an underlying linear relationship. These studies are premised on the assumption that whether public debt is increasing or decreasing, the reaction of economic growth to changes in public debt level should be the same and proportional which might not be correct. To discover the long-run relationship between public debt and economic growth, such research mainly adopted the linear co-integration and error-correction modeling estimation approaches. While these methodologies allow for the assessment of both long-run and short-run relationships, they are often unsatisfactory in estimating potential asymmetries in public debt–growth relationships. The issue of how debt affects growth remains relevant in African economies. Many economically fragile states are already behind on their debt service obligations, necessitating debt restructuring. Furthermore, even in countries where the public debt burden is manageable, debt service obligations have taken an increasing share of government revenues. Analysts are concerned that if left unchecked, this current wave of rising debt will resurrect the debt crisis of past decades in several highly indebted African countries. It is troubling that the recent episode of declining growth rates in Nigeria coincides with the country’s episode of growing debt, which began in the aftermath of the global financial crisis. This study was motivated not only by the dearth of research on the nonlinear impact of government debt on growth in Nigeria, but also, more generally, by the possibility that this relationship may be different from that described in the literature due to variations in key country-specific determinants of economic performance.

While many studies have examined the relationship between public debt and economic growth, none of them has looked at both disaggregation and non-linearities simultaneously. Accordingly, the current study departed from the symmetrical assumption by separating changes in disaggregated public debt indicators into their partial sum of positive and negative changes. Using data covering the years 1980 through 2020 and the Nonlinear Autoregressive Distributed Lag (NARDL) approach, the study investigated the individual effects of positive and negative changes in public debt measures on economic growth in Nigeria. The study differs from panel-based studies, which have a tendency to generalize the conclusions of a single regression estimate across a wide range of economies with varied country-specific debt experiences. The disaggregated analysis is motivated by the possibility of an unbiased impact of public debt on economic growth due to data aggregation. Taking into account the disaggregated public debt measures may provide a better understanding of the foregoing relationship. In Nigerian public debate, public debt has frequently been weaponized, and at times grossly oversimplified, to the point where debt levels are frequently construed as a proxy for national economic success or failure. The rest of the paper is structured as follows. The theoretical underpinnings of the investigation are presented in the next section. The methodological concerns and econometric approaches are discussed in the third section. The fourth section discusses the empirical findings and their implications. The study is concluded in the fifth section, which also makes policy recommendations based on the study’s findings.

Theoretical framework

There is a wealth of research on the pathways through which public debt affects economic growth in both develo** and developed countries, but the majority of it assumes that the relationship is symmetric, with little emphasis on the nonlinear relationships between debt and economic growth in the African context, despite the abundance of empirical evidence on the subject. Since changes in public debt indicators can have varying degrees and directions on economic growth, the presumption of symmetric impact of public debt may not be exact. Sachs (2002) explained the nonlinear relationship between debt and economic growth using the debt Laffer curve. According to this theory, there is a point at which public debt activates economic growth and any additional debt has a detrimental effect. As unpaid debt exceeds a certain threshold, the country’s repayment capacity begins to deteriorate. More specifically, when a country obtains debt to finance budget deficits, it increases the availability of resources for investment activities, which may boost growth. Borrowing beyond the peak point, on the other hand, results in debt overhang and debt service issues. Sachs (2002) envisioned the nonlinear hypothesis to explain debt overhang. Excessive government borrowing causes inefficiencies, which eventually have a negative impact on economic growth. As a result, according to this theory, the relationship between government debt and economic growth is nonlinear (Komlan and Essosinam 2022).

Public debt may have a beneficial or negative impact on economic growth through a variety of ways. The displacement of private investments is the most frequently mentioned negative effect, and macroeconomic fragility is another negative impact. The beneficial outcomes depend on the expansionary fiscal policy’s capacity to reduce both the actual rate and the natural rate of unemployment during recessions. Despite its widespread use, public debt has frequently been criticized by academics, pundits, and policymakers. Various economists have argued for and against the use of public debt, focusing on its economic utility, economic pitfalls, and intergenerational equity. However, these debates remain largely inconclusive, with evidence supporting both pro and anti-public debt positions. Many commentators appear to be taking positions based on ideology rather than empirical evidence, further obscuring much-needed clarity (Martin and Aleš 2020). The debt overhang theory and debt crowding-out arguments, which are detailed below, are two conflicting hypotheses put out to explain the link between public debt and economic growth.

Debt overhang hypothesis

Debt overhang, according to Bongumusa et al. (2022), Sachs (2002) and Krugman (1988) occurs when a country’s debt payment burden is so high that a considerable share of current GDP goes to loan guarantees, creating a disincentive to investment. It refers to creditors’ lack of trust in the debtor country’s capacity to completely recoup its debt. As a result, debt servicing is regarded as an implicit tax, inhibiting investment and limiting economic prosperity, making it virtually hard for heavily indebted countries to overcome poverty. Debt overhang can overwhelm an economy by lowering the quality of investment and the efficiency of government expenditure (Komlan and Essosinam 2022). As Àkos and Istvàn (2019) argued, in the context of poor countries, servicing huge public debt depletes the indebted country’s revenue, causing instabilities and slowing growth, to the point where the country’s potential to return to growth paths is bleak, even if robust reform plans are implemented. Heavy debt burdens also induce capital flight by increasing devaluation concerns, tax increases, and a need to safeguard the true worth of capital assets (Festus et al. 2022). Domestic savings and investment are reduced as a result of capital flight, limiting tax base, debt servicing ability and economic growth. Diverting foreign exchange to debt servicing limits import capacity, international competitiveness, and investment thereby constraining growth (Madow et al. 2021).

According to the debt overhang concept, lowering the face value of future debt obligations will boost the debtor’s capacity for investment and repayment because the distortion brought on by the implicit tax will be lessened. There is a limit to how much debt accumulation may encourage economic growth because when this effect is large, the debtor is said to be on the “wrong side” of the Laffer curve (Eze et al. 2019). In addition to capturing the overhang effect, the Laffer curve debt–growth model also takes into consideration the nonlinear effects of public debt. The presence of a well-established “Laffer curve” investigates the relationship between debt’s positive contribution to economic growth up to a predetermined point (the maximum threshold) and its subsequent negative impact. This argument contends that slower growth rate correlate with higher debt levels resulting from the higher capital tax burden necessary to finance public debt (Chinanuife et al. 2018).

Debt crowding-out hypothesis

The conventional hypothesis holds that an upsurge in government debt is a liability on succeeding generations, especially in the long run (Jhingan 2010; Bhartia 2008). Using domestic and foreign borrowing to finance government deficit, interest rates, disposable income, and wages may all rise, which would diminish corporate profitability and, consequently, private investment. This could deter or crowd-out private investment and reduce the level of productivity in an economy (Coulibaly et al. 2019). Given the rapid rise in public debt, a consumer may deem himself to be richer and, as a result, succumb to higher spending. Improved demand for goods and services will raise output and employment in the short run. Since the marginal propensity to consume exceeds the marginal propensity to save, a boost in private savings eventually diminishes in contrast to a deficit in public savings. As a result, real interest rates in the economy would rise, encouraging capital inflows from abroad via foreign investment. Higher interest rates would stifle growth and crowd-out private sector participation in a market-driven economy in the long run. Lower investment leads to a reduction in both invested capital and aggregate output. The net result is a decrease in consumption, reduced welfare and economic growth (Ogunjimi 2019).

The classical economists view debt as a form of state-imposed future taxation. They believe that public debt prevents present and future generations from accumulating wealth and from enjoying life to the fullest. They suggest kee** government borrowing as minimum as possible due to crowding-out of private investment. Where public spending is necessary, it should be restricted to investment in critical infrastructure that increase productive efficiency of the economy (Komlan and Essosinam 2022). In situations where governments use heavy borrowing to fund spending, the resulting pressures in the credit market may result in higher interest rates, which in turn slow down overall private investment. In this way, the classical economists argue that government spending through heavy borrowing from the domestic financial markets crowds out private sector investment thereby impeding a country’s natural growth process because the government diverts scarce resources that could be used effectively in the private sector to pay for systemic mismanagement (Malachy et al. 2022). This claim made a strong case that governmental debt is bad for the economy, especially if it weakens both the fiscal restraint of the budgeting process and the financial inclusion of the private sector (Àkos and Istvàn 2019). According to the classical economists, government debt-financed spending cannot fully compensate for the detrimental effects of private investment competition, which results in economic stagnation. According to this school of thought, domestic public borrowing results in liquidity crises and higher interest rates, which deter private investment.

The neoclassical school of thought contends that fiscal deficits increase interest rates, discourage the issuance of private bonds, private investments, and private spending, raise the level of inflation, cause an equal increase in current account deficits, and ultimately slow economic growth by crowding-out resources (Festus et al. 2022). This school’s supporters make the case for a strong fiscal strategy to support stable macroeconomic conditions that would encourage sustained economic activity. They claim that by scaring away private investment, a liberalization of fiscal policy is harmful to production growth. Since the government typically concentrates on ineffective spending with limited potential for ongoing development of macroeconomic conditions commensurate with long-term economic expectations, the liberalization of fiscal policy not only raises interest rates but also inhibits business activity (Bongumusa et al. 2022).

Because of the investments it produces, debt does not place a burden on either present or future generations, according to Keynesians. According to this strategy, debt accelerates a more proportionate increase in investment, which in turn stimulates a rise in production because debt increases demand. On the other hand, a typical Keynesian perspective holds that public sector spending financed by debt has a crowding-in effect, which has a positive multiplier effect on national output (Mhlaba and Phiri 2019). The Keynesians use the expansionary impacts of budget deficits as a counter argument to the crowding-out effect. They assert that budget deficits increase domestic production, aggregate demand, savings, and private investment at any given level of interest rates, increasing private investors’ confidence in the direction of the economy and leading to increased investment (Eze et al. 2019). According to the Mundell-Fleming framework, a rise in the budget deficit would push interest rates higher, bringing in capital and increasing the value of the currency, which would increase the current account balance.

According to Bongumusa et al. (2022), increasing aggregate demand boosts the profitability of private investments and encourages more investment at any given interest rate. Therefore, even if they boost interest rates, deficits may encourage overall savings and investment. Along these lines, they draw the conclusion that "crowding in" has occurred rather than investment being “pushed out” by deficit financing. Higher government spending has the potential to slow development by crowding out private sector spending, according to opponents of the Keynesian hypothesis. This is especially true if the public spending is financed by borrowing. Therefore, the crowding-out effect reduces the government’s ability to affect the economy through fiscal policy (Babalola and Onikosi-Alliyu 2020). According to the monetarist theory, after a brief time of adjustment, the growth in government spending crowds out or displaces private spending of a comparable size. In order to finance budget shortfalls, governments may issue more currency than is typically necessary. This practice is known as “monetary financing” (Chinanuife et al. 2018). Although given a constant demand function for base money, inflation will occur when the rate of increase in money supply exceeds the rate of growth of economic activity (Ndoricimpa 2020).

Malachy et al. (2022) contended that it is improbable that rapid money supply growth occurs in situations when governments generate money to cover budget deficits without fiscal imbalances. Given a fixed supply of money, rising transaction costs and an increase in the amount of debt available on the market cause interest rates to rise. Business and possibly even government spending are decreased by the rise in interest rates. The crowding-out hypothesis’ overall conclusion is that, barring an increase in the money supply, economic growth in the government sector will always be at the expense of the economy’s private sector (Festus et al. 2022). According to Barro’s (2013) Ricardian equivalence hypothesis, attempts at fiscal stabilization have no effect on economic growth. This theory states that future taxes with a present value equal to the debt’s worth will be required in the event that the government’s debt increases as a result of deficit financing. The debt should, therefore, have no impact on economic activity because rational agents should notice this equivalence and operate as if it did not even exist. According to adherents of the Ricardian Equivalence Hypothesis, rational economic agents modify their savings in anticipation of future taxes that would be used to pay off the debt, and this has no effect on consumption, output, or employment (Saungweme and Odhiambo 2019).

Data and methodology

This study combined ex-post facto and quantitative research designs to provide empirical answers to the research issues utilizing data that is already validated by experts and publicly available. The dataset which is of the secondary source were extracted largely from the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN), Debt Management Office (DMO), the World Bank and International Monetary Fund World Development Indicators statistical database using the desk survey approach. The macroeconomic variables on which data were collected included the Real Gross Domestic Product (RGDP), External Debt Stock (EDS), Government Domestic Debt (GDD), Foreign Reserve Position (FRP), Debt Service Payment (DSP) all in nominal terms and policy control variable Inflation Rate (INFR). Data on RGDP, EDS, GDD, FRP and DSP which were taken in monetary terms were log-transformed to stabilize the variance of the series while INFR retained its percentage form. E-views 12 statistical package was utilized for data analysis.

The economic modeling of variables in the model specification is supported by theories such as the debt Laffer curve and the endogenous growth theories. For the endogenous growth theories, government policies and institutions serve as influences that could have a direct impact on long-term economic growth. Government policies, therefore, contrary to neoclassical thought, are central to the long-term success of economic growth. Thus, countries with high level of efficiency, appropriate economic system, sound economic policy, tend to grow more rapidly (Romer 1986; Lucas 1988). The dependent and independent variables employed in this analysis were selected after taking into account the underlying economic theories and empirical research on the effects of public debt on economic growth in emerging nations. It has been shown in econometric studies that the omission of pertinent variables from a regression model results in bias, the magnitude of which depends on the interaction of the omitted variable with the other explanatory factors and the dependent variable (Gujarati and Porter 2009).

The linear ARDL assumes that information asymmetry has a symmetrical effect on economic activity. Since the increase or decrease in public debt indicators may have an impact on economic growth with varying degrees and orientations, the assumption that public debt has a symmetrical impact may not be entirely accurate. We follow Shin et al. (2014) and differentiate positive and negative changes in public debt predictors to test the symmetry versus asymmetry effects of public debt on economic growth. Changes in public debt predictors are, therefore, decomposed into positive and negative deviations to assess the asymmetric effect of public debt on growth in the short and long run. According to Shin et al. (2014), two new time series variables are created: POS, which represents only the increase in public debt as a partial sum of positive changes, and NEG, which represents the decrease in public debt as a partial sum of negative changes. RGDP, used as a proxy for economic growth and the dependent variable, is, therefore, stated as a function of positive and negative changes in EDS, GDD, DSP, FRP, and INFR in the growth model developed for this study in order to prevent variable omission bias. Decomposing LnEDS, LnGDD, LnDSP, LnFRP, and INFR into their respective positive and negative changes, within the framework of an unrestricted error-correction model (ECM), as specified in the following equation, allowed us to define the asymmetric impact of government debt on economic growth in Nigeria:

where RGDP is the socioeconomic indicator used in this analysis to assess annual economic growth over the review period. Theoretical research suggests that RGDP can be used as a precise indicator of economic growth. It is a statistic that accounts for inflation and expresses the worth of all finished products and services produced annually in terms of a base year price.

FRP = represents a country’s foreign reserves that are the total amount of cumulative foreign exchange surpluses that can be utilize to pay down current debt. Foreign exchange could be earned from export of goods and services, foreign direct investment inflows, grants and aids, capital repatriations, external loans, etc.

INFR = is inflation rate which measures the annual percentage growth in consumer prices. Rapid increases in the overall price level are bad for growth because they raise borrowing costs and slow down capital investment. The rate of inflation is crucial because it indicates how quickly an investment’s real value is eroding and how much spending power is being lost over time. While the other explanatory factors in the equation remain as previously described, INFR was accepted as a conditioning variable to compensate for the volatility in price changes that affects company predictions and the standard of living of the population.

Ln is the natural logarithm of the respective variables. \(\Delta\) stands for the first differences of the respective variables and q is the lag length for each variable. The asymmetric long-term impacts of positive and negative changes in the model’s explanatory variables are represented by β+ and β− while \(\varnothing\)+ and \(\varnothing\)−− denotes the short-run dynamic coefficients for positive and negative deviations in indicators of government debt related to the model’s convergence to long-run equilibrium. In the event of a disturbance, the ECT is the speed of adjustment parameter that transmits the pace of convergence or how rapidly the variables returned from short-run disequilibrium to long-term equilibrium. The coefficient must be negative and statistically significant in order to achieve long-run equilibrium. The coefficient’s value provides the long-run annual path to equilibrium GDP. A test of the disturbance term, µt, can confirm that the regression includes an adequate lag length. The lag lengths included are adequate if the error series is serially uncorrelated and symptomatic of a white noise process.

Estimation procedure

Existing literature on the impact of public debt on economic growth is dominated by linear models that assume in general symmetric relationships. A few studies focused on nonlinearity and examine long-run nonlinear relationships based on asymmetric GARCH, EGARCH models and regime-switching models. Zhou (2010) stated that when data are nonlinear, tests for linear co-integration are mis-specified and tend to reject the existence of co-integration. As a result, it appears critical to examine the presence of short- and long-run nonlinear effects and, if found, estimate the asymmetric response of economic growth to changes in public debt measures. In two ways, the study adds to the existing literature. This paper’s first contribution is to decompose changes in public debt measures into their partial sum of positive and negative changes in order to investigate whether these changes have asymmetric effects on economic growth. The nonlinear ARDL approach, as opposed to the linear ARDL approach, allows for the separate estimation of the impact of public debt increases and decreases on the trajectory of economic growth. This is an important issue because the linear ARDL model implicitly assumes that the impact of government debt on economic growth is symmetric, which is unrealistic (Mourad and Ousama 2019).

The nonlinear ARDL, on the other hand, relaxes this assumption because the coefficients on public debt increases and decreases are assumed to be significantly different from each other, implying that the effects of public debt increases and decreases are asymmetric. It would thus be delusional to evaluate the public debt–economic growth nexus using only a linear-based framework. Shin et al. (2014) applied the positive and negative partial sum decompositions to test for the asymmetric response of a dependent variable on an independent variable(s). This study, therefore, adopted a multiple test of stationarity and the nonlinear ARDL method developed by Shin et al. (2014) which allows for the separation of positive and negative changes in public debt parameters for the simultaneous testing of the short and long-run asymmetry in the relationship between public debt and economic growth in Nigeria. The asymmetric Unrestricted ARDL co-integration approach allows for the joint analysis of non-stationarity and nonlinearity issues in the context of an unrestricted error-correction model (ECM).

The NARDL method allows for the decomposition of public debt indicators into positive and negative partial sum of squares and their long and short-term effects on growth tested. This methodology presents important advantages over the existing classical co-integration modeling techniques (such as the Error Correction Model (ECM), the threshold ECM, the Markov-switching ECM, the Smooth Transition ECM, Smooth Transition Autoregressive (STAR) model and the quantile regression method in modeling jointly the co-integration dynamics and asymmetries (Abderrazak and Sami 2017). Despite allowing for the analysis of the impact of public debt on economic growth, the linear ARDL methodology explicitly assumes that this influence is symmetrical. Similar to this, it is believed that the error-correction term of this strategy will respond to economic volatility linearly and at a constant speed. However, this might not be the case if time series respond asymmetrically, implying that they react differently to economic forces pooling positively or negatively away from the equilibrium. In addition, application of linear ARDL would result in inconsistent and non-robust estimates, resulting in the wrong policy conclusions (Duygu 2018). By breaking down the changes in public debt indicators into their partial sum of positive and negative deviations and then estimating the nonlinear version of the ARDL model, the nonlinear ARDL technique avoids such an incorrect conjecture.

In contrast to the ECM, which is binding in this respect, the NARDL model offers more flexibility in waiving the restrictions that the time series should be integrated of the same order. This is in addition to its estimate efficiency. No matter if the regressors are stationary at level or at first difference, the NARDL approach can be used. However, it cannot be used if the regressors are I(2). It also shows better performance when evaluating for co-integration relationships in small samples and permits one to differentiate precisely between the presence of co-integration, linear co-integration, and nonlinear co-integration. It essentially functions as a proactive error-correction representation, producing reliable research evidences even with limited sample sizes. The NARDL model enables the simultaneous modeling of co-integration and asymmetric nonlinearity among the fundamental variables in a single equation system. Moreover, the NARDL dynamic multipliers adapt to the newly discovered long-run equilibrium from earlier disequilibrium dynamics, providing new insight into how their asymmetric shocks affect growth (Abdulkarim and Mohd. 2021b).

There are 5 main steps in the NARDL estimation process. To make sure that none of the variables are integrated of order two (I(2)), we first carefully evaluate the stationarity characteristics of the variables under examination. Second, by breaking down the respective public debt variables into their positive and negative deviations, we construct the component sum of positive and negative changes. The best lag length for each variable in the model is then chosen using an appropriate lag selection method based on criteria like the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and a variety of others. AIC, in particular, is a metric of the relative strengths of a predictive method that balances goodness-of-fit and sophistication. Less information is lost and a better fit is indicated by smaller AIC-value and F-Wald values (Rahman and Islam 2020). To determine whether the variables under consideration are nonlinearly co-integrated, carry out the asymmetric co-integration test. The NARDL model is invalid if no co-integrating link is found. Finally, if co-integration is present, we calculate the asymmetric response of economic growth to fluctuations in the indices of public debt and use the Wald test of coefficient restriction to determine whether there are short- and long-run asymmetries (Abdulkarim and Mohd. 2021b). The following are the details for the Wald test’s null and alternate hypotheses:

H0: β+ = β-- (Wald test proposition for symmetric long-run coefficient).

HA: β+ \(\ne\) β— (Wald test assumption for asymmetric long-run coefficient).

H0: \(\emptyset\)+ = \(\emptyset\)−− (Wald test premise for symmetric short-run coefficient).

HA: \(\emptyset\)+ \(\ne\) \(\emptyset\)−− (Wald test claim for asymmetric short-run coefficient).

Results and discussion

Preliminary analysis of study variables

Before estimating the model, it is critical to conduct a preliminary analysis of the data series. As a result, two traditional preliminary estimation techniques, namely descriptive statistics, correlation analysis and stationarity tests were used. These preliminary analyses provided a general idea of the nominal data set by describing the main attributes of the study variables in our model to establish if the data series are normally distributed and suitable for running the OLS regression. Descriptive statistics help to understand and ascertain the outliers, dispersions, and normality of the data series. The summary of descriptive statistics of the study variables in their nominal form is presented in Table 1.

The level of volatility in the variables is depicted by the standard deviation in Table 1. It shows how far away from the mean each variable deviates. The data’s asymmetry is shown by the data’s skewness. All the variables under investigation are positively skewed, which indicates a somewhat heavy-right tail, according to the data in Table 1. The sharpness of a normal distribution curve’s peak is gauged by kurtosis. In the RGDP and FRP series, platykurtic distribution is evident with kurtosis values under 3. According to this, these series create outliers that are less frequent and less extreme than those found in the normal distribution. However, EDS, GDD, DSP and INFR series show evidence of leptokurtic distribution with kurtosis value greater than 3. This indicates that these variables are with higher-than-normal kurtosis and the weight in the tail of their population density function is larger than normal.

The Jarque–Bera statistics measures how well sample data fit a normal distribution in terms of skewness and kurtosis. The null hypothesis is firmly accepted for these observations, as demonstrated by the probability values of the Jarque–Bera statistics for the RGDP and FRP series. As a result, these variables can be said to have a normal distribution since their corresponding Jarque–Bera probability values have a significance level of larger than 5%. The EDS, GDD, DSP, and INFR series, on the other hand, show substantial Jarque–Bera probability values of less than 0.05, which clearly show a lack of normalcy in their residuals. This suggests that these variables are highly susceptible to shocks and other fluctuations in the economy which may have caused outliers, resulting in residual non-normality. The Jarque–Bera probability for all the logged variables except INFR showed that they are normally distributed for the purpose of our regression analysis. However, normality of data distribution is not required to apply the NARDL co-integration method used in this study (Rahman and Islam 2020).

Table 2 correlation matrix examines the variables for collinearity. Researchers often rely on correlation coefficient and Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) test among pairs of predictors to measure the severity of multi-collinearity on the accuracy of estimated regression coefficients (Babu et al. 2020; Robert 2007). The study, therefore, inspected the degree of linear dependency and level of multi-collinearity problems among the explanatory variables specified in the empirical model using the Spearman rank-order correlation coefficient. The correlation analysis does not, however, infer any measure of causality or causal relationship between the examined variables.

From Table 2, multi-collinearity among the indicators of public debt explicitly stated in the model does not pose a serious challenge since the correlation coefficients of these variables were detected to be within the acceptable threshold limit of \(\pm\) 0.80 (Gujarati and Porter 2009; Babu et al. 2020; Rahman and Islam 2020). Nevertheless, one should be cautious in interpreting high correlation coefficient or high VIF values of the variables as evidence of high degree of multi-collinearity (Robert 2008). Robert (2007) emphasizes that it is important to compare VIF (and tolerance) threshold values to other factors affecting the variance of the regression coefficient. Values of the VIF of 10, 20, 40, or even greater do not, by themselves, discredit the conclusions of regression studies, suggest the use of ridge regression, or support the integration of two or more independent variables into one new variable to address multi-collinearity complications. Similarly, many recent studies have suggested that multi-collinearity may not necessarily be a problem and the frequently used method of resolving multi-collinearity issues in regression analysis may sometimes create bigger problems than the ones they seek to correct (Nguyen 2020; Babu et al 2020; Robert 2007).

Tests of stationarity for examined variables

In order to assure a non-spurious estimation and to evaluate the time series efficiently, all the study variables are pre-tested for unit root issues because time series data are susceptible to unit root problems. It is also necessary to verify the stationarity of the time series to ensure that none of the variables are integrated beyond one (I(1)) to guarantee the validity of the co-integration bounds test (1). The sequence of integration of the variables under investigation was checked for this purpose using both conventional and structural breakpoint methods. This is important because econometric analysis of non-stationary variables affects the accuracy and reliability of empirical results.

The Dickey and Fuller (ADF) and Phillips–Perron (PP) unit root tests of stationarity, which are the norm, are typically ineffective in the presence of structural break. A break is a recurring shock that affects a time series over an extended period of time. The ability to veto a false unit root null hypothesis will be limited if this break is not explicitly addressed during the unit root review process (Glynn et al. 2007). The Zivot and Andrews (1992) unit root test was used to fully account for unobserved heterogeneity in the variables under study and demonstrate how susceptible the estimated results are to structural changes. The Zivot and Andrews test uses an endogenous sequential test to discover each potential break in the entire sample using several dummy variables. The unit root tests results are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3 shows that the conventional and structural breakpoint unit root tests yielded similar results. The tests show that only DSP and INFR are level stationary (integrated of order zero). The rest of the variables—RGDP, EDS, GDD and FRP were found to be stationary after differencing them once. The variables can, thus, be said to be integrated of order one. It can, therefore, be concluded that the variables under consideration are levels and first difference stationary, but no variable was stationary at second difference. The dependent variable was also stationary at first difference, indicating that the NARDL method’s conditions were fulfilled. After meeting the preconditions for using the NARDL estimation method, the researcher was confident that the co-integration analysis using this method would produce credible and reliable regression coefficients.

NARDL asymmetric co-integration test analysis

Once the order of integration of variables is established by unit root testing and the optimal lag length is determined using the relevant criteria such as (Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), Schwarz Bayesian Criterion (SBC), and Hannan-Quinn Criterion (HQC)), the bounds test within the NARDL model developed by Shin et al. (2014) can be used to determine whether there is co-integration between the variables. The null hypothesis states that there is no long-run relationship between the variables in the model, while the alternative hypothesis states it exists. Statistically, this can be tested by restricting the long-run coefficients to jointly equal zero using Wald test. The co-integration between the variables is determined if the F-statistic exceeds the critical values of the upper bound using Narayan (2005), who provided the upper and lower bounds F-statistics for a short sample size (30–80 observations).

The NARDL model’s investigation of the nonlinear response of economic growth to positive and negative variations in the indicators of government debt depends critically on the choice of the ideal lag length. Annual observations are collected for the study, which has a sample size of 39 and 6 parameters. Considering the small number of observations and the need to maintain degrees of freedom, the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) was used to choose an ideal lag length of 2 that was imposed on the dependent variable and the dynamic regressors. This ensured that the model dynamics were not restricted by too few lags and the selected model has no issues of serial correlation. Equation 1 was, therefore, estimated using an optimally determined lag structure of (2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 1, 2, 2, 2, 1, 2) being the most efficient of the estimated models. The results obtained from the NARDL asymmetric co-integration, and the estimated F-test are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4 indicated that the calculated F-statistic of 19.948 is greater than the upper bound critical value of 3.86 at the one percent significance level, evidencing the fact that a long-run nonlinear relationship exists between the predictors of public debt explicitly stated in the model and economic growth in Nigeria during the review period. The findings confirmed that the NARDL model in Eq. 1 is correctly specified and valid and that any short-run deviation in the relationship between public debt and economic growth in Nigeria would return to equilibrium in the long run.

Long-run asymmetric effects of public debt on economic growth in Nigeria

The conditional NARDL model stated in Eq. 1 was estimated to determine the long-run asymmetries between the investigated variables. Table 5 shows the estimated long-run coefficients on the asymmetric effects of public debt on economic growth in Nigeria.

The long-run coefficient of positive change in external debt (LnEDS POS) is statistically significant at the 5% level and favorably connected to economic growth. According to the findings, an increase in foreign debt stock of one percent while kee** other explanatory variables constant led to an increase in economic growth of 0.6%. In develo** countries apart from saving gap they face, there is also foreign exchange constraint (gap) required for importation of capital goods. Consequently, external debt is required to provide capital funds for the importations of capital goods which has a positive effect on efficacy and productivity. External debt can boost growth rate by stimulating investment in critical infrastructures, efficient allocation of resources and increased productive capacity. The results support the neoclassical growth theories and conventional wisdom which suggest that government external borrowing is a major source of liquidity and capital accumulation which, if productively invested can boost long-term economic growth.

In a similar vein, the long-run coefficient of negative deviation in the stock of external debt (LnEDS NEG) revealed an inverse association with economic growth that is noteworthy at the 5% level of probability, indicating that a rise in economic growth can be instigated by a decrease in the level of external debt. According to the findings, a rise in economic growth of around 0.32% was correlated with a percentage point decrease in the stock of external debt. The results are in accord with the assertion of Krugman (1988), Pattillo et al. (2011), and Rogoff and Reinhart (2010) that public debt accrued beyond a sustainable threshold will constitute a perilous fiscal logjam on the pathway to economic growth. The null hypothesis of a symmetric relationship between external debt and Nigeria’s economic growth was not rejected by the Wald test, which had a coefficient restriction probability value of 0.897. Therefore, there is little evidence in the analysis to suggest that external debt had an uneven long-term effect on economic growth in Nigeria over the review period.

From the results in Table 5, the long-run coefficient of positive change in government domestic debt (LnGDD_ POS) is negatively related with economic growth and statistically significant at 5% level, suggesting that higher domestic debt is harmful to growth. Specifically, a percentage point increase in domestic borrowing, other things remaining equal, prompted a decrease of about 0.22 percent in economic growth. The negative sign and relatively high coefficient of domestic borrowing shows the increasing use of deficit financing in Nigeria’s fiscal operations. The result indicates that increasing the stock of domestic has a debilitating effect on long-term growth, due largely to high implicit domestic interest rate, poor utilization and inefficiency in domestic administration, thus confirming the domestic debt overhang hypothesis. Government uses domestic savings to finance domestic borrowing. As a result, there are less funds available for private lending, which increases the cost of capital for individual borrowers and decreases the need for private investment and growth. Due to the disastrous consequences of prior debt management mistakes, significant arrears, fines, and interest accrued over time. The effects of these include the fact that paying off debt required money that should have gone toward infrastructure and human development, which had a negative impact on Nigeria’s long-term economic progress.

However, the response of economic growth to negative change in government domestic debt (LnGDD_NEG) is positive but statistically inconsequential. The use of short-term domestic loans with high interest rate to finance recurrent expenditure as is the case in Nigeria, servicing such debts could present a significant burden to the budget thereby constituting an impediment to economic growth. A probability value greater than 0.05 was obtained using the accompanying Wald test of coefficient limitation. As a result, the null hypothesis of a symmetric relationship between the two variables was accepted by the Wald test statistic. Because of this, the study could not find enough evidence to conclude that domestic debt had an asymmetric long-term effect on economic growth in Nigeria throughout the study period.

According to Table 5, the long-run coefficient of positive deviation in debt service payments (LnDSP_POS) triggered a negative relationship with economic growth that is statistically insignificant. According to the crowding-out theory, public debt has a detrimental impact on growth in develo** nations because the resources required to service it result in a loss of limited foreign currency that could have been invested productively in infrastructure, slowing progress. Foreign creditors effectively take away a large portion of the profits obtained from investments in the local economy as debt servicing costs rise. New foreign investment is completely discouraged in conjunction with this withdrawal. This will adversely affect capital formation in a significant way. Debt servicing effectively shifts money away from domestic markets and into international markets, which has some severe multiplier accelerator effects that limit economic growth while massively increasing the economy’s reliance on foreign debts (Stanley et al. 2019). However, the insignificant coefficient of this variable can be attributed to the fact that most of Nigeria’s external borrowings are concessional loans at low interest rate and longer maturity period.

Similarly, the coefficient of negative change in debt service payments (LnDSP_NEG) elicited an unimportant positive effect on long-term economic growth. The result though not statistically significant, demonstrated that a decrease in debt service payments can boost long-term economic growth in Nigeria. Although the Wald test probability value of 0.1007 failed to rule out the null hypothesis of a symmetric relationship between debt service payment and economic growth in Nigeria, the Wald test statistic did not find any conclusive evidence to support the long-term asymmetric impact of debt service payment on economic growth. The findings are in line with those of Saxena and Shanker (2018) and Stanley et al. (2019), who found that debt service payments had a considerable negative impact on long-term economic growth in India and Nigeria, respectively. Massive public debt payment expenses could take up a bigger amount of tax revenue, resulting in macroeconomic distortions and slowed growth.

At a 1 percent probability level, the long-term economic growth responded favorably and significantly to improvements in the foreign reserve position (LnFRP POS). According to Table 5, a percentage increase in foreign reserve position, while holding other explanatory variables constant, resulted in a rise in long-run economic growth of approximately 0.32 percent. Similar to the long-run coefficient of negative change in foreign reserve position (LnFRP NEG), this effect is statistically significant at the one percent level and spurred an increase in economic growth. According to Table 5, a percentage point drop in foreign reserves, with all other factors remaining the same, caused a 0.50% drop in long-term economic growth. Foreign reserves are kept on hand to cover financing needs for the balance of payments, to intervene in exchange markets to influence foreign exchange rates, and to protect the global value of the domestic currency (Awoderu et al. 2017). Whenever there is a deficit position at the end of a period, some of the accumulated reserves of the previous periods are utilized to regularize the deficit, and finance imports stabilize the exchange rate of the domestic currency, stimulate growth and increase the international competitiveness of the domestic economy.

In the absence of adequate reserves to support current account payments, the deficit country may resort to borrowings from trade creditors, international monetary fund, international money and capital markets or from other international lending agencies to clear the deficits or to refinance the rescheduled debt which had matured. The accompanying Wald test of coefficient restriction probability value of 0.0165 which was less than 0.05 confirmed significant evidence of an asymmetric impact of foreign reserve position on long-term economic growth in Nigeria during the review period. The results support the findings of Kashif et al. (2017) who reported a significant positive effect of foreign reserves holding on long-term economic growth in Brazil. According to conventional knowledge, good management of international reserves could be a major factor in boosting long-term economic growth.

According to Table 5, the long-run coefficient of positive change in inflation rate (INFR_POS) displayed an inverse relationship with economic growth that is significant at five percent probability level. Based on the results, a percentage increase in inflation rate, holding other explanatory variables constant, initiated a decrease of approximately 0.004% in economic growth. Similarly, the response of long-term economic growth to negative change in inflation rate (INFR_NEG) showed a direct or positive relationship that is statistically significant at one percent probability level. Specifically, a percentage point decrease in inflation rate, other things remaining equal, produced about 0.004% decrease in long-term economic growth.

In addition, the Wald test of coefficient restriction probability value of 0.0322 failed to reject the null hypothesis of an asymmetric long-run relationship between inflation rate and growth in Nigeria during the review period. Increased costs reduce discretionary income and make people poorer. Consumers’ ability to purchase products and services declines as a result of income erosion brought on by price increases, which results in a decline in standard of life. The results showed that in order to raise Nigeria’s long-term economic growth rate, a modest increase in the general level of prices for goods and services is needed. The variable’s low coefficient value points to the necessity to regulate the general level of inflation because an unbridled upward trend in prices could spiral into hyperinflation, which would cause a catastrophic decline in the value of money, low savings, and, expectedly, would actively prevent private investment growth.

Short-run asymmetric effects of government debt on economic growth in Nigeria

The study estimated the unrestricted Error Correction Model (ECM) of the NARDL model described in Eq. (1) and the associated Wald test of coefficient restriction in order to examine any possible short asymmetries between public debt indicators and economic growth in Nigeria. The short-run characteristics of the model’s transition to equilibrium are summarized in Table 6.

The model’s lagged error-correction term (ECT(-1)) captures the dynamic long-run relationship and is correctly signed (negative) and statistically significant. The coefficient of the error-correction mechanism in a single equation must lie between − 1 and 0. Otherwise, the error-correction term is explosive. The coefficient of the lagged error-correction term in Table 6 is significant at the 1 percent level and has the right sign, demonstrating a consistent long-term nonlinear relationship between the measures of government debt and economic growth in Nigeria. The coefficient implies that approximately 73.45% of the current year’s deviation from the long-run equilibrium level of output is corrected over the succeeding year. Because of the relatively high pace of adjustment, any short-run glitches should take about 1.36 years to recover from and return the economy to its long-run optimum growth path.

The current rate of economic growth in congruence with the long-run results is favorably correlated with the short-run coefficient of positive changes in the current level of external debt D(LnEDS POS) but statistically negligible. Consistent with the long-term findings, the predictor of negative change in the current level of external debt, D(LnEDS NEG) generated a negative influence on the current rate of economic growth and is significant at the one percent probability level. Particularly, a percentage point reduction in the stock of current external debt sparked a 0.05% increase in the current pace of economic growth. In line with the long-run outcome, the Wald test probability value of 0.1207 also supported the existence of a symmetric link between the stock of external debt and short-run economic growth in Nigeria over the examined period.

In addition, the coefficient of positive change in the current level of government domestic debt, D(LnGDD POS), in agreement with the long-run results showed a negative impact on the current rate of economic growth that is statically important at the one percent probability level, suggesting that higher levels of domestic debt slow down current GDP growth rates. To be more precise, a percentage point rise in the prevailing level of domestic government debt was linked to a 0.27% decline in the rate of economic growth. Similar to this, the rebuttal of the ongoing rate of economic growth to negative change in the current level of domestic government debt D(LnGDD NEG) in agreement with the long-run results demonstrated a favorable influence on the present rate of economic growth that is statistically notable at one percent probability level. The findings show that a percentage point decline in the existing level of domestic debt is responsible for a 0.81% deterioration in the rate of economic growth. The Wald test probability value of 0.0058 in contrast to the long-run results, however, provided compelling evidence of an asymmetric short-run influence of government domestic debt on the pace of economic growth in Nigeria at the time.

Table 6 shows that the short-run coefficient of positive deviation in the current level of debt service payments D(LnDSP POS) in accordance with the long-run results recognized a negative influence on the current rate of economic growth that is clinically meaningful at the 5 percent level. According to the findings, a percentage rise in the present level of debt service payments triggers a 0.011% fall in the current rate of economic growth while maintaining other explanatory variables constant. Similar to the long-run results, the current level of debt service payment’s current level of negative deviation D(LnDSP NEG) showed a negligible negative impact on the rate of economic growth. Furthermore, the Wald test probability value of 0.6649 in line with the long-run results revealed no statistical support for the existence of a short-run asymmetries in the impact of debt service payments on the rate of economic growth in Nigeria over the examined period.

In addition, Table 6 demonstrates that the short-run coefficient of positive shock in the current level of foreign reserve holding D(LnFRP POS) in concert with the long-run results is favorably associated with the current rate of economic growth and highly meaningful at the one percent probability level. According to the findings, the prevailing rate of economic growth will increase by around 0.05% for every percentage point that the country’s foreign reserves were increased, all other factors being the same. In contrast, the predictor of adverse shock in the current level of foreign reserve holding D(LnFRP NEG) in disagreement with the long-run findings caused a detrimental effect on the present rate of economic growth that is statistically relevant at the one percent probability level. The findings show that, other things being equal, a percentage point decrease in the current level of foreign reserve holding led to a 0.12% rise in the current pace of economic growth. The variable’s low coefficient values highlight the monolithic structure of the Nigerian economy as a result of its sole reliance on highly volatile oil exports to generate hard currency. Considerable evidence is offered in favor of a symmetric short-run influence of kee** foreign reserves on the prevailing rate of economic growth in Nigeria by the underlying Wald test probability value of 0.0852 in contradiction with the long-run estimates.

According to Table 6 findings, the short-run coefficient of positive deviation in the current rate of inflation, D(INFR POS), showed a negligible positive impact on the current rate of economic growth. The reaction of the present rate of economic growth to negative variation in the current inflation rate D(INFR NEG) in comparison with the long-run results also demonstrated an adverse effect that is noticeable at the one percent probability level. According to the findings, while kee** all other explanatory variables constant, a rise in the current rate of inflation caused a boost in economic growth of around 0.002%. In line with the long-run findings, the subsequent Wald test of coefficient restriction probability value of 0.0494 found strong proof to support the existence of a short-run asymmetric influence of the prevailing inflation rate on the current pace of economic growth in Nigeria.

Robustness checks

The NARDL models’ validity, stability, and fulfillment of the desirable statistical assumptions of an effective NARDL model were all evaluated by a number of diagnostic tests at the end. The regressors were tested for serial correlation to confirm they did not share a serial correlation, the residuals were tested for normality to guarantee they are normally distributed, and lastly, the model was tested for heteroscedasticity to certify there is no ARCH effect. In addition, the stability of the NARDL models was assessed using CUSUM (Cumulative Sum of Recursive Residuals) and CUSUMsq (Cumulative Sum of Squares of Recursive Residuals). The results of the diagnostics tests are presented in Table 7.

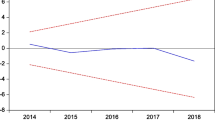

According to the diagnostics testing results in Table 7, the model’s residuals are normally distributed and show no signs of multi-collinearity, serial correlation, heteroscedasticity, or model misspecification error. Because the aforementioned traits are desirable characteristics of OLS models, the estimated model is deemed to be properly specified. The CUSUM and CUSUM of squares tests, which are depicted in Figs. 1 and 2, also confirmed that our model’s long-run and short-run estimated parameters are dynamically stable over a range of structural adjustments and that the estimated results are precise and sufficient for economic forecasts and decision-making.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Nigeria has accumulated massive public debt that is rapidly becoming insolvent and unsustainable since the debt relief in 2006 in exchange for prudent economic management and effective poverty-reduction measures. The purpose of this study is to assess the validity of the debt Laffer curve theory in Nigeria’s public debt–growth relationship. In addition, the study investigated the possibility of nonlinearity between government debt and economic growth in Nigeria using data from 1980 to 2020 and the NARDL assessment method. This helps us understand the extent to which government debt is harmful to the economy, despite the fact that it has traditionally been used as a tool to keep the economy running. The NARDL co-integration result showed a distinct long-run nonlinear relationship between economic growth and the selected government debt parameters. The asymmetric long-run findings demonstrate that positive changes in external debt stock is positively correlated with GDP growth rates, implying that increases in foreign debt stock will enrich long-term economic growth. Negative changes in the stock of external debt noticeably improve long and short-term growth. In the long and short run, the analysis found no evidence to establish an asymmetric correlation between external debt stock and real GDP growth rate. Positive changes in domestic debt are discovered to be growth-inhibiting and significant in both the long and short run, whereas negative changes in domestic debt are observed to be growth-inhibiting but significant only in the short run. The Wald test results confirmed the presence of an asymmetric short-run influence of domestic debt on economic growth and a symmetric long-run relationship.

The empirical results also showed that negative changes in debt service payment had a negligible beneficial impact on long-term growth while positive changes in debt service payment retarded growth in the short term. The accompanying Wald test results showed significant evidence in support of a symmetric relationship between economic growth and debt service payments both in the long and short run. While a decrease in stock of foreign reserve greatly inhibited growth in the long run but encouraged growth in the short run, increase in the stock of external reserves significantly stimulated growth in both the long and short run. The analysis discovered substantial evidence in favor of a long-run asymmetric link between the stock of external reserves and economic growth and a short-run symmetric association. In addition, while increases in general price level subdued growth in the long run, they only have an inconsequential positive impact on growth in the short term. Conversely, negative changes in price level considerably accelerate growth in the short term. Price changes revealed an asymmetric relationship with economic growth both in the long and short run during the review period.

The study findings have implications for economic policy. In addition, controlling the public debt is crucial to preserving Nigeria’s long-term growth. In a post-Covid world with high inflation and fragile growth, structural policies and technological advancement can be crucial in ensuring a vibrant, environmentally friendly, and inclusive economy. Governments should find this challenging at a time when the Covid 19 pandemic has increased budget deficits in most nations, and public debt is one strategy for dealing with the crisis and maintaining public services. Governments must, therefore, have a good policy for monitoring the advantageous level of debt if they are to be able to respond robustly to economic shocks and debt crises, protect jobs, make profitable investments, and ensure economic sustainability. The government should also apply the lessons it has learned from previous debt crises to address the economy’s structural flaws, which may include boosting investment and skill-building. In addition, in times of crisis, having a low debt-to-GDP ratio may be advantageous, hel** to mitigate the impact of any resulting shocks. Finally, economic and social stability necessitate a robust social security safety net capable of relieving citizens of the burden of economic pressure during a crisis. As a result, the paper proposes that government loans be directed toward the country’s economic expansion and diversification in order to foster long-term economic growth. Economic diversification will not only reduce high macroeconomic volatility caused by large swings in export prices, but it will also broaden the country’s revenue base, improving the country’s ability to repay financial obligations when they become due.

The policy implications of the study finding are for government to increase its stock of external debt and reduce domestic borrowing to stimulate higher rate of growth in the long term. While domestic borrowing can be used to promote the development of the domestic capital and money market, control inflation, conserve scarce foreign exchange and the repayment of the principal and interest constitute a reinvestment with a multiplier effect on domestic investment in the economy, the findings suggests that Nigeria should opt for external financing of its investments in soft and hard infrastructures mainly because of the perceived savings deficit in domestic capital markets, lower interest rate and longer maturity period. Due to vested interests, rent-seeking behavior, and state capture, it is difficult for develo** countries, Nigeria included, to effectively utilize foreign debt. However, only in the presence of sound macroeconomic policies and state institutions does external debt have a positive impact on economic growth. Given that Nigeria is an emerging economy that requires private capital to bridge its resource gap, build critical infrastructure that drive long-term growth, what is needed is fiscal reforms that effectively reduces deficit financing, improve domestic revenue generation and infrastructure spending, as well as strengthening corporate governance and institutions. This is important if the country is to resolve its debt crisis, regain its creditworthiness, control inflation and improve productivity. The fact that debt service payments have a negligible impact on long-term growth furthers the idea that government borrowing must be done on terms that will not only ensure fiscal discipline but will also benefit the nation’s long-term economic growth.

The results of the study also demonstrated a long-term nonlinear relationship between the accumulation of external reserves and economic growth. This demonstrates the necessity to develop a solid knowledge-based, innovative, and diversified economy that is less vulnerable to fluctuations in the price of oil in order to boost foreign exchange earnings, enhance the country’s currency, global competitiveness, reduce debt, create jobs, and improve the living standards of the citizenry. The study findings also confirmed an expansionary fiscal policy which fuelled inflation in the long run. Harmonization of monetary and fiscal policies is, therefore, required to achieve overall macroeconomic stability; otherwise, the conflicting behavior of some macroeconomic variables would have a detrimental effect not just on other variables but also on the whole economy. A primary contributor to the fiscal imbalance that forces policymakers to rely on debt financing is the overly expansive public sector, high governance costs, unsustainable debt servicing costs, and defence spending. To minimize the adverse effects of inflation especially in the long run, the study, therefore, recommends controlling the growth of money supply, reduction in the cost of governance and deficit financing. Government is also encouraged to implement infrastructure asset recycling models where existing infrastructures can be turned over to the private sector or adopt a Public–Private Partnership arrangement to ramp up infrastructure and stem the increasing tide of deficit financing.

The findings of this study should be interpreted with caution, as they are based on country-specific variables, data collected during a specified timeframe, and a distinct econometric approach. Despite the fact that the current study provides novel insights into the asymmetric influence of public debt on economic growth in Nigeria, it has some restrictions due primarily to the lack of data and the econometric approach used. The domestic institutional framework, which includes good governance and effective public administration, is also crucial to understanding the relationship between economic growth and debt. Extensions of the present study might examine the nonlinear relationship between public debt and economic growth in Nigeria using a time-varying modeling technique like the Quantile ARDL and determine the point at which public debt starts to negatively affect growth in the presence of other exogenous factors.

Availability of data and materials