Abstract

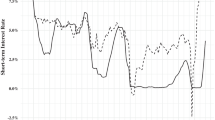

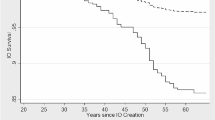

The Reserve Bank of India often claims that the official intervention in the foreign exchange market primarily aims at minimizing undue fluctuations in the exchange rate and this study is an attempt to explore the success story of such interventions. Although the stylized facts seem to indicate that maintaining adequate amount of official reserves help reduce the volatility, the marginal benefit of adding reserves in terms of containing excessive volatility declines as the level of reserve holding increases beyond certain threshold level. The evidence from a threshold vector autoregression model suggest that the response of exchange rate volatility is conditional upon the size of intervention and whether the level of reserve holdings is above or below certain threshold level. While the official purchase of foreign exchange reduces the variability of exchange rate, official sale seems to trigger volatility irrespective of whether reserve holding is above or below the threshold level. Further, a positive shock to absolute official sale (purchase) could reduce the pace of depreciation (appreciation) although it could not revert the direction of exchange rate. These evidences exemplify the fact that intervention cannot prevent exchange rate volatility from rising rather it can only moderate.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The time series data are collected from the Handbook of Statistics on Indian Economy published by the Reserve Bank of India.

Notes

The measure of reserves that we consider excludes gold.

First, there are monetary losses in opportunity cost sense and the possible loss arising out of valuation changes. Baker and Walentine (2001) report an opportunity cost of 10–20 percent while Rodrik (2006) report that it is 1 per cent of GDP for develo** countries. Rajan (2002) has produced some estimates ranging from 0.3 to 1 percent of GDP for five crises affected economies in East Asia in 1999. A recent study by Adler et al. (2021) reports estimates that ranges from 0.2 to 0.7 percentage of GDP per year in countries with limited intervention while reaching 0.3–1.2 percentage of GDP per year in heavy-intervening economies. The estimates for India indicate that there is a rise in the cost of holding reserves from 0.51 percent of GDP in 2001-02 to 1.24 percent in 2007–08 (Mishra and Sharma 2011). Second, there are certain macroeconomic adjustment costs associated with heightened reserve holdings; running down reserves, if warranted, might result in undue appreciation of domestic currency which can conflict with other economic objectives (Willett (1980) and as a consequence, countries cannot reduce them even if they move into a flexible exchange rate regime (Sula 2011). Further, there are cost arising out of sterilization of capital inflows; moral hazards; and also, high reserve holding might reflect insurance against weak domestic fundamentals and high political uncertainty (Kapur and Patel 2003). Moreover, Ramachandran (2004) demonstrates that the opportunity cost impacted the reserve demand more significantly than other conventional determinants.

See Heller (1968) for a detailed exposition of this issue.

See Flenders (1971) for a detailed discussion on the importance of all these factors that determine the transaction demand for reserves.

There are evidences to show that rise in the volatility of cross-border capital flows subject to sudden stops/reversal are largely responsible for reserve accumulation in emerging economies (Calvo,1998; Flood and Marion 2002; Edwards 2004; Aizenman and Marion 2004; Aizenman and Lee 2005; and Arslan and Carlos 2019).

Cumulatively, high reserve holding countries have run down reserves to 3 percent of GDP while reserve depletion with low reserve holding countries is found to be 0.98 percent of GDP.

Reserve as import cover is considered relevant for countries with least transactions on capital account and three months coverage was used as a benchmark. However, with growing integration of financial markets across the world, the relevance of this measure is questioned and as a result, six months import coverage is considered as a threshold level. The ratio of short-term external debt to reserves is used as an indicator of crisis risk and played significant role in determining the adequacy of reserves especially in those countries with larger short-term cross-border financial transactions. In this context, the adequacy is widely determined by Greenspan-Guidotti rule, which states that the stock of reserves at any point in time must be 100% of short-term external debt.

Albania, Argentina, Belarus, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Chile, Colombia, Croatia, Gabon, Georgia, Hungary, India, Indonesia, Jamaica, Kazakhstan, Republic of Korea, Malaysia, Mauritius, Mexico, Moldova, North Macedonia, Paraguay, Peru, Philippines, Poland, Romania, Serbia, Seychelles, South Africa, Thailand, Republic of Turkey, Ukraine, Uruguay.

The relevance of a number of control variables which could have impacted the exchange rate volatility are tested using block exogeneity test and only those turned out to be important are consider in the model.

Monthly data on import is used as an indicator variable for interpolation.

The response of volatility to negative shocks in most cases is found to be symmetric to the responses of volatility to positive shocks.

References

Adler, G., T. Mora, and E. Camilo. 2011. Foreign Exchange Intervention: A Shield Against Appreciation Winds? IMF Working Paper No. 11/165.

Adler, G., K. S. Chang, M. Rui, and S. Yuting. 2021. Foreign Exchange Intervention: A Dataset of Public Data and Proxies. IMF Working Paper No. 2021/047.

Aghion, P., P. Bacchetta, R. Ranciere, and K. Rogoff. 2009. Exchange rate volatility and productivity growth: The role of financial development. Journal of Monetary Economics 56: 494–513.

Aizenman, J., and J. Lee. 2005. International reserves: precautionary versus mercantilist views, theory and evidence. NBER Working, Paper No. 11366.

Aizenman, J., and N. Marion. 1999. Reserve uncertainty and the supply of international credit. NBER Working Paper No. 7202.

Aizenman, J., and N.P. Marion. 2004. International reserves holdings with sovereign risk and costly tax collection. Economic Journal 114: 569–591.

Arize, A.C. 1995. The effects of exchange-rate volatility on US exports: An empirical investigation. Southern Economic Journal 62: 34–43.

Arize, A.C., T. Osang, and D.J. Slottje. 2000. Exchange-rate volatility and foreign trade: Evidence from thirteen LDC’s. Journal of Business & Economic Statistics 18: 10–17.

Arslan, Y., and C. Carlos. 2019. The size of foreign exchange reserves, Bank for International Settlement Paper No. 104a.

Baker, D., and K. Walentin. 2001. Money for nothing: the increasing cost of foreign reserve holdings to develo** nations. Center for Economic and Policy Research, Washington, DC.

Balke, N.S. 2000. Credit and economic activity: Credit regime and nonlinear propagation of shocks. Review of Economics and Statistics 82: 344–349.

Barabás, G. 2003. Co** with the speculative attack against the forint’s band. MNB Background Studies 2003/3.

Bar-Ilan, A., N. Marion, and D. Perry. 2007. Drift control of international reserves. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control 31: 3110–3137.

Bleaney, M., and D. Greenaway. 2001. The impact of terms of trade and real exchange rate volatility on investment and growth in sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of Development Economics 65: 491–500.

Caballero, R., and A. Krishnamurthy. 2001. A “vertical” analysis of crises and intervention: fear of floating and ex-ante problems. NBER Working Paper No. 8428.

Calvo, A.G. 1998. Capital flows and capital-market crises: The Simple Economics of Sudden Stops. Journal of Applied Economics 1: 35–54.

Calvo, A. G., and C. M. Reinhart. 2000. Fear of floating, NBER Working Paper No. 7993.

Chang, R., and A. Velasco. 1998. Financial crises in emerging markets: a canonical model, NBER Working Paper No. 6606.

Chowdhury, A.R. 1993. Does exchange rate volatility depress trade flows? Evidence from error-correction models. The Review of Economics and Statistics 75: 700–706.

Demir, F. 2010. Exchange rate volatility and employment growth in develo** countries: Evidence from Turkey. World Development 38: 1127–1140.

Disyatat, P., and G. Galati. 2007. The effectiveness of foreign exchange intervention in emerging market countries: Evidence from the Czech Koruna. Journal of International Money and Finance 26: 383–402.

Drummond, P., and A. Dhasmana. 2008. Foreign reserve adequacy in Sub-Saharan Africa, IMF Working Paper, WP/08/150.

Durdu, C.B., E.G. Mendoza, and M.E. Terrones. 2009. Precautionary demand for foreign assets in sudden stop economies: An assessment of the new mercantilism. Journal of Development Economics 89: 194–209.

Edwards, S. 2004. Thirty years of currency account imbalances, currency account reversal and sudden stops. IMF staff papers 51. International Monetary Fund, Washington D C.

Feldstein, M. 1999. A self-help guide for emerging markets. Foreign Affairs, March–April.

Flenders, M. 1971. The demand for international reserves. Princeton Studies in International Finance, No. 27.

Flood, R., and N. Marion. 2002. Holding international reserves in an era of high capital mobility, IMF Working Paper. WP/02/62.

Guérin, J., and A. Lahrèche-Révil. 2001. Exchange rate volatility and growth, Document de Travail Des XVIIIémesJournéesInternationalesd’ÉconomieMonétaire, Juin, Lisbonne.

Haberler, G. 1977. How important is control over international reserves? In The New International Monetary System, ed. Robert A. Mundell and Jacques J. Polak, 111–132. New York: Columbia University Press.

Heller, R.H. 1968. The transactions demand for international means of payments. Journal of Political Economy 76: 141–145.

Kapur, D., and U.R. Patel. 2003. Large foreign currency reserves: Insurance for domestic weakness and external uncertainties? Economic and Political Weekly 15: 1047–1053.

Keefe, H.G., and H. Shadmani. 2018. Foreign exchange market intervention and asymmetric preferences. Emerging Markets Review. 37: 148–163.

Li, J., O. Sula, and T. Willett. 2008. A new framework for analyzing adequate and excessive reserve levels under high capital mobility. In China and Asia. Routledge Studies in the Modern World Economy, ed. Y. Cheung and K. Wong, 230–245. New York: Routledge.

Mishra, R.K., and C. Sharma. 2011. India’s demand for international reserves and monetary disequilibrium: Reserve adequacy under floating regime. Journal of Policy Modeling 33: 901–919.

Mohanty, M. S. 2013. Market volatility and foreign exchange intervention in EMEs: what has changed? Bank of International Settlements No.73.

Oskooee, M.B., and M. Malixi. 1987. Effects of exchange rate flexibility on the demand for international reserves. Economics Letters 23: 89–93.

Pattanaik, S., and S. Sahoo. 2003. The Effectiveness of Intervention in India: An Empirical Assessment. RBI Occasional Papers 22: 21–52.

Pontines, V.S., and R. Rajan. 2011. Foreign exchange market intervention and reserve accumulation in emerging Asia: Is there evidence of fear of appreciation? Economics Letters 111: 252–255.

Raddatz, C. 2006. Liquidity needs and vulnerability to financial underdevelopment. Journal of Financial Economics 80: 677–722.

Radelet, S., and J.D. Sachs. 1998. The East Asian financial crisis: Diagnosis, remedies, prospects. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 29: 1–90.

Rajan, R. 2002. International reserve holdings by develo** countries: Why and how much? Economic and Political Weekly 37: 915–1917.

Ramachandran, M. 2004. The optimal level of international reserves: Evidence for India. Economics Letters 83: 365–370.

Ramachandran, M. 2006. On the upsurge of foreign exchange reserves in India. Journal of Policy Modeling 28: 797–809.

Ramachandran, M., and S. Carmel. 2018. Appetite for official reserves. Economic and Political Weekly 53: 121–128.

Ramachandran, M., and N. Srinivasan. 2007. Asymmetric exchange rate intervention and international reserve accumulation in India. Economics Letters 94: 259–265.

Reddy, Y. V., 1997. The dilemmas of exchange rate management in India, Inaugural Address to the XIth National Assembly Forex Association of India, Goa, India.

Rodrik, D. 2006. The Social Cost of Foreign Exchange Reserves. International Economic Journal 20: 253–266.

Sahay, H., and M. Ramachandran. 2022. Official interventions in the foreign exchange market: implications for exchange rate and its volatility. In Studies in international economics and finance, ed. Y. Naoyuki, R.N. Pramanic, and A.S. Kumar, 541–556. Springer.

Srinivasan, N., V. Mahambare, and M. Ramachandran. 2009. Preference asymmetry and international reserve accretion in India. Applied Economics Letters 16: 1543–1546.

Sula, O. 2011. Demand for International Reserves in Develo** Nations: A Quantile Regression Approach. Journal of International Money and Finance 30: 764–777.

Willett, T. 1980. International Liquidity Issues, American Enterprise Institute, Washington D.C.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Dr. D. Sambandhan and Dr. N. R. Bhanumurthy for valuable comments on an earlier draft of this paper. Thanks are also due to Dr. Hersch Sahay, Keerthana Sunny George and Namshad for technical support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix A

Objectives of Official Intervention

Name of the countries | Objectives |

|---|---|

China | To keep the exchange rate stable at an adaptive and an equilibrium level |

Japan | To stabilize the value of the exchange rate |

Switzerland | To align the exchange rate in line with monetary policy to influence the monetary conditions |

Euro area | To maintain price stability |

India | To avoid undue fluctuations in exchange rate |

Taiwan | To avoid fluctuations in exchange rate arising out of seasonal and irregular events |

Russia | To support financial stability and to service external debt for several years, even in times of distress |

Hongkong | To fix the exchange rate |

Korea | To ensure stability in the foreign exchange market |

Saudi Arabia | To fix the exchange rate |

Singapore | To fix the exchange rate |

Brazil | To contain disorderly movements of the exchange rate |

US | To counter disorderly market conditions |

Thailand | To accumulate reserves which help in fulfilling the monetary and exchange rate policies |

Israel | To meet external obligations, counter forex market crises and improve the country’s financial credibility |

Mexico | To contain exchange rate volatility and thereby ensure financial stability |

United Kingdom | To check undue fluctuations in the exchange rate |

Czech Republic | To be used as an instrument of monetary policy |

Poland | To curtail excess exchange rate volatility |

Indonesia | To counter demand and supply mismatches in the forex market which help in achieving exchange rate stability as well as currency liquidity simultaneously |

United Arab Emirates | To fix the exchange rate |

Malaysia | To reduce undue exchange rate volatility, secure orderly conditions in the forex market |

Vietnam | To maintain stability and control inflation |

Canada | To promote orderly market conditions for the national currency |

Philippines | To bring in monetary stability, check excessive exchange market speculation and to reduce sudden and sharp capital movements |

Norway | To curb excess volatility of the exchange rate |

Appendix B

The construct of weekly time varying conditional volatility of percentage change in ₹/$ exchange rate is obtained using the following EGARCH specification:

where \({\widehat{\rm E}}_{t}\) is weekly percentage change in ₹/$ exchange rate. The p-values in parentheses indicate that all the coefficients, excepting constant in the mean equation, are found to be statistically significant. The estimated \({\chi }^{2}\) statistic is found to be 5.067 with a p-value of 0.16; suggesting that the null of no autocorrelation in the standardized residuals (\({\nu }_{t}\)) upto a lag order of 4 can be accepted. The F-statistic to test the null that there is no remaining ARCH effect upto 4th lag in the square of the standardized residuals is estimated to be 0.571 with a p-value of 0.68; suggesting that the EGARCH specification is appropriate to model exchange rate volatility.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Ramachandran, M. Official Intervention, Reserve Accumulation and Exchange Rate Volatility. J. Quant. Econ. 21, 269–287 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40953-023-00344-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40953-023-00344-z