Abstract

Urban American Indian/Alaska Native (AI/AN) young adults and their families are often geographically or socially distant from tribal networks and traditional social support. Young adults can be especially vulnerable to cultural and social disconnection, so understanding how AI/AN family functioning can augment resilience and protect against risk is important. This research precedes a preventive substance use intervention study and explores urban Native family functioning, emphasizing the role of young adults by analyzing data from 13 focus groups with urban AI/AN young adults (n = 32), parents (n = 25), and health providers (n = 33). We found that young adults can and want to become agents of family resilience, playing active roles in minimizing risks and strengthening family functioning in both practical and traditional ways. Also, extended family and community networks played a vital role in sha** family dynamics to support resilience. These resilience pathways suggest potential targets for intervention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Background

American Indians and Alaska Native (AI/AN) people exhibit some of the most dramatic health disparities in the USA, much of which may be explained (directly and indirectly) by centuries of collective historical trauma [1]. This is an important status risk brought about by long-term government policies of forced displacement, urban relocation, and forced assimilation that have eroded cultural systems and traditional support networks [2]. As a result of decreased cultural connections and the ability to access support from extended families and elders, these policies have also led many AI/AN individuals to be exposed to poverty and intergenerational trauma (i.e., trauma that is experienced collectively and passed on between generations), sometimes leading to alcohol and other drug use (AOD) and poor health [3]. Today, approximately 70% of all AI/AN people reside outside of reservations or tribal lands [4], where many young adults experience additional stressors due to cultural disconnection, poverty, and violence [5, 6]. However, our understanding of risk and resilience among urban AI/AN families through the lens of urban AI/AN young adults is limited. This is important to recognize because furthering our understanding of risk and resilience can inform the development of substance use prevention interventions to create healthier urban AI/AN communities.

Unique Aspects of AI/AN Families

Family functioning plays a key role in risk and resilience [7], for example, buffering effects of historical trauma [8]. Whereas in Western models the family unit revolves around the nuclear family (parents and children) [9], families in many AI/AN communities include extended and communal families, where grandparents, other relatives, and tribal elders play prominent roles in guiding and supporting individuals and families [10]. However, forced relocations and other forms of oppression have separated families and eroded the fabric of AI/AN family life [10].

There is, of course, much diversity in family life across the AI/AN population. For example, AI/AN families living on reservations are more likely to rely on extended family (e.g., multiple generations living in one household) [11], or other tribal relations [12]) for practical purposes (e.g., economic support, caregiving) and moral/spiritual guidance [13]. On reservations, the extended family also plays a role in reinforcing cultural beliefs and values [14]. In contrast, AI/AN people in urban settings are often less connected to tribal networks and traditional support, and extended family networks may include more non-AI/AN individuals [13]. In addition, urban AI/AN people may have fewer opportunities to engage in traditional practices [15], which may decrease their sense of AI/AN identity, values, and belonging, with implications for family health, social and emotional adjustment, educational attainment and employment [3]. Furthermore, AI/AN people may move back and forth from rural to urban areas to stay connected with their families or to access services. Evidence suggests that while maintaining close ties to reservations and cultural practice [16], many urban AI/AN families are resilient, adapting to urban life by participating in Native traditional activities in urban communities [17, 18].

Family Resilience in Urban AI/AN Communities

Resilience is embedded in family functioning across populations [19]. The literature on resilience has been conceptualized around either processes or outcomes, with some noting that processes may be more useful for practical applications [20]. The Family Resilience Model, for example, conceptualizes resilience across individual, family, and community systems, including the presence of family risk, protective factors, family vulnerability to risk, and adaptive mechanisms [21]. Examples of protective processes are the use of family skills and capabilities to prevent or manage stressors, whereas vulnerability to risk may include family daily challenges and difficulty managing hardships[21]. At the individual level, a protective factor can manifest itself through a parent who is responsive and present, whereas adequate housing and supportive community relationships illustrate protective factors at the family and system levels respectively [21]. The experience of historical trauma represents a focal risk, whereas vulnerabilities are illustrated by individual mental health challenges, family risk statuses (e.g., being a minority group), family breakdown (e.g., divorce), and family experiences, such as intergenerational trauma [21]. This model centers on family adaptive systems, which refers to family processes (e.g., building meaning, emotional control, meeting basic needs) that occur within the family ecosystem and larger social systems to regulate family functioning in response to stressors and risks [21, 22]. At an emotional level, protective adaptation may include family members showing support for each other, whereas adaptation through making meaning is illustrated by conversations about how the family relates to specific situations or where they fit in the grand scheme of life [21]. It is also possible for families to experience maladaptation to vulnerabilities, such as AOD use [21].

Recent work has re-envisioned AI/AN resilience as a dynamic collective adaptation to overcome stress, driven by family beliefs and values, and by the interactions among family members as they manage their resources to promote wellbeing [23]. In response to sustained hardship, AI/AN communities exhibit striking resilience at both the family and community levels [24]. Understanding how resilience manifests at the family ecosystem level within specific cultural and socio-economic contexts, i.e., what factors pose risks or what mechanisms confer protection, is important for develo** interventions. For example, resilience often manifests in the family’s ability to support children and extended family members, and can also manifest through meaningful engagement with communities and elders, such as teaching AI/AN languages and traditional practices [25]. AI/AN traditional practices are diverse among the 574 federally recognized tribes that exist in the USA [26], ranging from beading or drumming to specific traditional ceremonies like sage ceremony, which aims to cleanse and promote healing [27]. When some of these protective processes are available in abundance, they can represent a strength and a buffer to risk, but when they are sparse, it may contribute to family vulnerability to risk. Many life lessons are taught through these practices and participating in them connects AI/AN people to culture, the community, and can influence their worldview [28]. Research has also shown that engagement in traditional practices increases resilience by promoting AI/AN adults’ well-being, including reducing anxiety and depression [29], decreasing hypertension [30], and hel** teens make healthy choices around AOD use [18].

Gaps in Understanding Family Dynamics Among Urban AI/AN Families

To date, research on family dynamics among AI/AN individuals has focused predominantly on the impact of family structure [31, 32], parental cultural socialization [33], and culturally-based parenting [34, 35]. For example, AI/AN parenting has been found to focus on encouragement, exploration, modeling, and storytelling more than confrontation and questioning [36]. AI/AN parents also have been found to emphasize direct experiences that can help teach their children important lessons [37]. Cohesion among AI/AN families is both internal (e.g., feeling close to family members, supporting each other through crises) and external (e.g., involving community members in family problem solving) as AI/AN people tend to participate in large support networks for both mundane tasks and broader life guidance [38]. However, little is known about both the role of young AI/AN adults (aged 18–25) in AI/AN family resilience, and the role of the family in supporting young AI/AN adult resilience. The family resilience model [21], with its adaptive approach, for example, suggests that family and community members other than parents (e.g., young adults) may play an active role in managing risks and strengthening family functioning.

Much prior work on AI/AN family dynamics resonates with Primary Socialization Theory, which posits that individual behaviors are learned through reciprocal relationships within families, peer networks, schools, and the broader socio-cultural context [39, 40]. In AI/AN culture, socialization, and experiential learning occur within a cultural framework that includes elders’ storytelling and cultural and traditional practice and allows negative experiences and relationships to coexist with and often complement positive experiences and relationships [41]. This enables a more flexible framework for negotiating complex family dynamics [38]. Understanding the unique role of urban young adults in navigating this cultural framework within the context of family functioning is crucial for identifying resources needed to support urban native families.

Evidence suggests the potential for culturally-centered substance use prevention and treatment interventions to help enhance resilience among urban AI/AN adolescents and adults [18]. However, there are few studies that assess resilience for urban AI/AN families with young adult children, and there is limited qualitative work focused specifically on the practical implications of family dynamics for intervention development to increase resilience among urban AI/ANs [5].

Qualitative data, such as focus group transcripts, can shed light on urban family dynamics related to resilience. One strength of qualitative data is their use in generating hypotheses and uncovering new processes that may critique preexisting theoretical frameworks. This information can be useful in conceptualizing and designing culturally-tailored interventions that address issues beyond typical Western notions of parenting (e.g., family and collective community resilience, problem-solving, and communication), which evidence suggests could be particularly helpful for urban AI/AN families [3, 13].

Study Goal

This study sought to enhance our understanding of risk and resilience among the AI/AN family ecosystem within the urban setting with a focus on the urban AI/AN young adult experience. This paper moves the field forward by describing perceptions of AI/AN family dynamics, including historical trauma and its consequences, resilience and adaptation, and traditional practices among urban AI/AN communities, with a focus on young adults. We further wanted to understand family dynamics in urban contexts, how families were connected to support from traditional AI /AN sources, how this influenced family processes, how urban families support resilience in young adults, and how young adults envision their role in family resilience. We conducted 13 focus groups with urban AI/AN young adults, parents, and health providers to understand the urban native experience with a view to collecting information to use in develo** a substance use prevention intervention for young adults.

Methods

Sample and Recruitment

Traditions and Connections for Urban Native Americans (TACUNA) is a longitudinal, mixed-methods clinical trial study involving quantitative (survey) and qualitative (focus group) data collection [42]. Phase I was formative, focused on the development of a culturally appropriate substance use prevention intervention that addresses opioid, alcohol and marijuana, and other drug use. The current analysis relies on focus groups conducted as part of Phase I.

We recruited young adults (aged 18–25), parents, and providers to participate in focus groups held at AI/AN community centers across southern, central, and northern California. Eligibility criteria for participants included: residence in urban areas and self-identification as AI/AN (for parents and young adults); and for providers, experience treating AOD for AI/AN young adults (not all providers identified as AI/AN). Participants were recruited through advertisements at community events and community partner sites. In addition, we enlisted the help of AI/AN recruiters in southern, central, and northern California who had worked with our team on previous projects. Much of this effort was coordinated through our partner, Sacred Path Indigenous Wellness Center, which engages AI/AN urban communities in California in a culturally grounded manner. All recruitment, data collection, and analytic procedures were approved by our Institutional Review Board. Participants were offered $50 gift cards as remuneration for the two-hour session and provided demographic information, such as age, sex, and tribal affiliation. To protect participant identity, we do not report tribal affiliation.

Qualitative Data Collection

Focus groups were conducted in person between November 2019 and February 2020. We conducted six focus groups with young adults, four focus groups with parents, and three with providers. Because the focus of the intervention was on young adults, we planned to conduct two focus groups in southern, central, and northern California respectively, whereas for parents and providers we aimed to organize one for each group in the respective geographic regions. This was a pragmatic strategy, balancing the need for sufficient data with the logistical capabilities of our community partners. Due to the level of interest, we organized an additional focus group for parents in southern California. Each focus group lasted about two hours, with an average of seven participants. Each focus group was moderated by several members of our research team, and was audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. All moderators had graduate-level training in qualitative interviewing, as well as prior experience with qualitative data from other AI/AN studies. One of the moderators was an Alaska Native (Inupiaq).

The primary objective was to elicit information to help develop a culturally-centered intervention that integrates AI/AN traditional practices with motivational interviewing focusing on preventing substance use among AI/AN young adults [18, 43]. Questions (see Supplement 1) covered five domains based on the research team’s prior interventions, a review of the literature, the study’s scientific goals, and guidance from community members: (1) social relationships (e.g., healthy relationships, the pathway between social relationships and opioid use); (2) AI/AN identity (e.g., degree of connection to Native identity, experiences, traditions, connectedness); (3) opioid use (including non-medical use of prescription opioids and heroin use), alcohol, marijuana and other drug use (e.g., reasons why young adults may start using, risk and protective factors); (4) intervention content (e.g., feedback on proposed intervention materials, suggestions of preferred traditional activities, optimal strategies for engaging young adults); and (5) culturally sensitive intervention recruitment and retention (e.g., logistical aspects of recruitment, attendance barriers, suggested facilitators for attendance and retention). Although content related to family functioning was not directly solicited, discussions on this topic took place across all focus groups, and analysis of these discussions was used for this manuscript.

Data Analysis

We uploaded all transcripts to Dedoose, a software platform that facilitates collaborative management, analysis, and interpretation of qualitative data [44]. The two lead authors (AIP and RAB) employed a two-stage coding process to develop the codebook (see Supplement 2): first, we applied a set of basic codes that were built in the focus group protocol; second, we explored the thematic range and meaning grounded in the data [45]. We used open coding (i.e., labeling content according to the dimensions emerging from the text) and in vivo coding (i.e., labeling content using words directly from the text) to establish categories and themes that emerged directly from the data. The unit of analysis was a meaningful block of discussion, which in some cases included paragraph-level answers by one participant. In others, it included answers from multiple participants. We used a hierarchical organizational strategy, i.e., subthemes captured coherent variations on a given theme. We reported all themes mentioned by at least one focus group. We quantified qualitative excerpts as a way to provide internal generalizability within the three groups of study participants, to correctly characterize the diversity of perceptions across participants, and to help us identify patterns that might not have otherwise been apparent [46].

The two lead authors coded the transcripts independently, then met to discuss differences of interpretation over several iterations. Coders were trained in qualitative methods in the context of health services research and anthropology; and both had significant prior experience both with the methodology employed and the subject matter. Thus, the analytic process may have occasionally drawn on assumptions and expectations associated with prior work. Both coders participated in the focus groups as moderators, and neither is AI/AN, but have previous experiences partnering with AI/AN communities. The authors elicited feedback from the research team on codebook definitions and data interpretation. Cohen’s kappa measured inter-coder reliability [47]. Initially, reliability for many themes and subthemes ranged between 0.6 and 0.79. For codes below 0.6, most of which occurred among subthemes, the two coders reconciled coding differences, refined definitions, and merged codes to address discrepancies. To ensure that the coding process was explicit and transparent, we documented decisions to modify definitions and strategies to correct for overlap** codes. This reconciliation process began with 5 overall themes, and 26 subthemes, and resulted in 9 themes, some with several subthemes, for a total of 10 subthemes.

Results

We conducted 13 focus groups across California, including 90 participants (32 young adults, 33 providers, and 25 parents). Table 1 presents a summary of participant demographics.

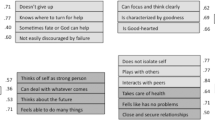

Nine themes (some with several subthemes) emerged around family dynamics. Below we discuss these themes, organized by risk (AOD use, trauma, and urban challenges and opportunities); and resilience (immediate family support, extended and community family support, adaptations to risky AOD settings, general family communication, family storytelling, and family engagement in cultural practices). Table 2 shows the presence of themes and subthemes by number of focus groups and type of participants. It quantifies the qualitative data, showing which themes and subthemes appeared more often, and whether certain themes were more prevalent among certain types of focus groups (parents, providers, and young adults).

Family Dynamics and Risk

Alcohol, Opioids, and Other Drug Use

Participants in all groups commented on the meaning of AOD use on reservations and in urban areas, which was observed in social settings (e.g., house parties, schools, and other public spaces), and also in some cases among immediate (e.g., parents, siblings), extended (e.g., uncles, aunts), and communal (e.g., elders) family. Narratives describing AOD use often suggested a bi-directional relationship between AOD use and family challenges, such as domestic violence, divorce, single parenthood, and parents losing custody of children.

When discussing personal AOD use, some young adults (1 out of 6 groups), parents (2 out of 4 groups), and providers (2 out of 3 groups) described how family influences led to their own personal use. In one young adult focus group participants described occasional use in the presence of other family members. Eleven out of 13 focus groups (4 out of 6 young adult groups, and all parent and provider focus groups) described witnessing AOD use in their immediate families, and the effects it had on other family members and on themselves. For example, a provider described how “my sister was influenced [in drug use] by a brother and a sister as well,” and a parent recalled that “my mom used alcohol for a co** mechanism, and as an adult I found myself going towards that, because that’s the only thing that I saw.”

Trauma

Across all focus groups, participants talked about several types of trauma. The meaning and impact of historical trauma were discussed in 12 of the 13 focus groups (all but one young adult group) through examples such as forced relocation to urban areas, forced enrolment in boarding schools, and other forms of oppression by the US government. One provider described how families have been affected by this trauma: “A lot of times when I meet with families in a Native home, the grandma probably experienced either the Relocation Act, forced assimilation, boarding school, child [loss], probably loss of culture, probably substance use disorder, probably depression.”

Many participants illustrated how historical trauma became intergenerational, sha** the health and well-being of descendants. One parent described the practical effects of this trauma: “What they’ve done to our people is very sad, and we’ve got to live with that every day. When it comes to drugs and alcohol, the poisoning, it affects us, from generation to generation.” In addition, some noted that intergenerational trauma can also impact cultural identity, as this young participant explained:

“My mom came from the reservation. She came down here, and I think so many bad things happened to her and her family that she didn’t want that element with us. And so … we obviously didn’t learn any traditional practices either.”

Finally, 3 focus groups (2 young adult groups and one provider group) described witnessing or experiencing other types of trauma, such as post-traumatic stress disorder associated with military service, and sexual and domestic violence and abuse. For example, one provider mentioned the traumatic experiences of their young adult patients: “When I say “complex trauma” I’m talking about they’ve been sexually abused or sexually molested. They’ve had child abuse, domestic violence in their house.”

Urban Challenges and Opportunities

Twelve focus groups (5 young adult groups, and all parent and provider groups) featured discussions about how urban environments presented challenges for life course development. They cited limited opportunities to advance in life due to lack of education and job prospects, limited life skills, and limited access to social safety nets. For example, one young adult explained how, faced with a lack of opportunities and positive role models, “there’s not really much to do, so there’s not really great choices to make.” A provider seconded this point, saying: “because there’s very little to do out there a lot of people turn to drinking, which happens at house parties. And then drinking turns into them getting curious about drugs.” Another young adult described how patterns of family relationships influence the sense of what is normal for a child to expect of their family:

“The dysfunction is so normal, it sucks how normal it is. If you have two parents and they’ve got jobs and you guys are going places on the weekend or something then you’re so lucky. It’s just not normal.”

Participants in 9 focus groups (3 young adult, 3 parent, and all 3 provider groups) talked about aspects of economic hardship that can affect AI/AN families daily, including insufficient money for transportation to and from job opportunities or traditional events, insufficient family capital or inheritance, the ever-increasing cost of living, and housing cost burden. One parent expressed the meaning of economic hardship and noted that lack of affordable housing was a major barrier in their children’s efforts to live on their own: “My boys have been looking for about a year. Just the studios and the one-bedrooms are over $2,000, and that’s not including [utilities].” Others pointed out that economic hardship forces many parents to work multiple jobs, which often reduces the amount of time they can spend parenting or being with family. One parent said, “Today, both parents have to work. Financially, the burden is on. So the kids, of course, they don’t want to be left alone and they want that guidance.” This burden is especially heavy on single parents, as suggested by this parent’s observation about another family: “She works in the evening, so she leaves her daughter unsupervised at night. The little girl was experimenting with drugs.” A young adult noted that economic difficulties can also affect the degree to which families can attend traditional events: “It’s mostly traveling [to pow wows] that's more expensive. And then being able to buy your materials for being traditional, those are pretty expensive.”

Young adults described the need for training and assistance to look for apartments and jobs, write checks, file taxes, and understand trade-offs between going to college and earning income from unskilled labor—suggesting opportunities for families to play a role in develo** such skill sets. Some participants who experienced life on reservations as well as in urban settings remarked on the advantages of living in urban settings. In contrast, one young adult focus group participant noted that urban AI/ANs could use “the privilege of living here in urban settings” to empower peers who live on reservations by introducing them to new skill sets, such as filmmaking:

“To us it’s so accessible that we take it for granted, but other people who are exposed to it for the first time are like, ‘Holy shit. I don’t have to be just like a carpenter for the rest of my life or I don’t have to work at a gas station for the rest of my life.’”

Family Dynamics and Resilience

Immediate Family Support

Participants across 7 focus groups (2 young adult, 3 parent, and 2 provider groups) described the importance of resources and social support from immediate and extended family during life crises or to help achieve life goals. Young adults mentioned relying on parents for help with basic needs, such as housing and transportation: “There’s a definite need for that, especially in today’s society, because it’s more prevalent now more than ever that a lot of adults stay with their parents until they’re like 30.” Parents sometimes expressed the need for mutual assistance during hard times: “They [my sons] feel like, “Mom, we’re going to have to stay with you for a couple more years.” And I was like, “I know this sweetie, just as long as you help me out. We’re in this together.”

Providers and parents discussed the meaning of the role that families could play in encouraging a range of life skills, including personal daily living skills (such as doing laundry) and soft professional skills. Several parents talked about supporting their children through life crises, such as being bullied at school. One parent described her involvement with her daughter’s schools and ultimately decided to help her daughter through homeschooling to protect her from bullying and discrimination. Another parent talked about getting her son into therapy after he had suffered a depressive episode:

“We did get him into therapy and then they did talk to him about stressors, like how to relieve that stress. … Within his group of friends, the parents, we’re all connected, and we know each other very well”.

Extended and Community Family Support

Discussions across 12 of the groups (all except 1 young adult group) focused on the meaning of positive aspects of the family structure in urban AI/AN families. Respondents described three “circles” of family: immediate family (parents and children), extended family (grandparents, aunts, uncles, cousins), and communal family (elders, AI/AN community centers). As discussed in the previous section, comments suggested that single parenthood was often difficult for participants; thus, many described the need to maximize support from the other family circles, i.e., extended and communal families. The extended family therefore played an important role in assisting with babysitting, hel** to provide healthy guidelines for child behavior, and providing guidance on Native traditions and healthy lifestyles (e.g., avoid drugs). One parent described how her immediate family helped develop more community connectedness; “My mom and her family started to teach our language. It did bring all the family and the community together.”

For many participants, the communal family (i.e., community organizations) provided important resources for families, including access to AI/AN education, opportunities for traditional practice, outdoor activities, networking, and services such as counselling. One young adult said, “I’ve been going to this youth program here since I was little. … And sometimes it would just be like they’ll take us to the park to play basketball. So, I got into sports more.” Parents sought out these community organizations for opportunities to attend family-centered events and traditional workshops. Attending events and workshops at these centers provided an opportunity to enrich family functioning and was protective. Many parents described the role of these centers as a natural extension of the immediate and extended family. One provider suggested using cultural centers to implement a more proactive approach to building a healthy communal family to support those who are at risk:

“We need more Auntie roles and Uncle roles. Because their family isn’t—we can’t expect them to be healthy. So because of that, we need to have them [Aunties and Uncles] be more visible in the community.”

Adaptation to Risky AOD Settings

Participants in 8 focus groups (4 young adult, 2 parent, and 2 provider groups) discussed creative ways in which they could mitigate the impact of family members who might be involved in substance use. First, some said they either temporarily stopped visiting relatives known to use AOD or reduced the amount of time they spent around them. Statements such as this one from a young adult were common:

“I think there’s a point where family is family, but you have to think about is this person good for me to have in my life? Because my grandma has seven kids and we don’t talk to any except my grandma, her husband, and then my mom, dad, and sister. Things happened in our lives where we had to say: they’re family but we can’t keep going through this.”

Participants also explained how exposure to AOD use in the family served as a cautionary tale to incentivize sobriety and substance-free living. Much of this was driven by the commitment to avoid the perceived physical effects of AOD use. Some parents explained that their sobriety was based on their desire to be role models for their children and to shield them from what they perceived to be the negative effects of AOD use, such as poverty, violence, and family instability. This position was illustrated as follows:

“My mom, my dad, my brother, and my other brother, they’re alcoholics. I know I went through a bad time, but I didn’t turn to drugs or alcohol. I had four kids at a young age and I had to do what I have to do for them.”

To avoid severing ties with family members, a few participants, predominantly young adults, described establishing sobriety rules for occasional family get-togethers, a strategy meant to keep problematic relatives at a distance, while still including them in family events:

“My husband and I decided we weren’t going to have alcohol or drugs in our household. It took a little for my parents, my family to get used to that. They had to get used to making sure they're sober when they come to my house. I can’t control what other people do, but I can control what happens in my own home.”

Finally, participants who described unhealthy home environments mentioned finding safe

places, such as libraries, where they could maximize the amount of time spent away from home.

Family Communication

Participants in 8 focus groups (2 young adult, 4 parent, and 2 provider groups) discussed aspects of family communication, including the importance of nurturing conversations with children. One parent said, “With my kids I’m very open, very honest. I think that makes our kids stronger.” Several parents also endorsed using a direct communication style with their children, especially with regards to drug use or other challenging topics: “My daughter, I talk to her about it. If she wants to know anything, I go ‘Come to me and I’ll tell you straight up.’ Like she wanted to know about sex and I told her. And then drugs.” Others focused on the need to listen with the intent to what children say about their feelings: “We talk a lot about drugs, alcohol, people’s behaviors, and how that affects them. [I]t keeps a little bit more healthy communication.”

Family Storytelling

Participant comments (2 young adult, 3 parent, and 2 provider groups) emphasized the importance of family stories about AI/AN heritage and how these stories could help bring families together. This was an important mechanism by which families made positive meaning of how they understood historical trauma and how they fit into the broader scheme of life. Many discussed storytelling around Native history and traditions shared among immediate and extended family members, for example, grandparents recounting their experience growing up on a reservation, or traditional practice, such as deer hunting:

“My grandpa used to tell us he was able to talk to the deer. He would go out, hunt for deer and he would talk to them and say, I have to feed my family. I'm going to come for you tomorrow. … They were very spiritual.”

Parents described using family tradition to reinforce Native identity, by reiterating statements to their children about family lineage, for instance:

“I told my youngest daughter, ‘I know you don't know your grandpa. but your grandma and your grandpa are full-blooded Navajo.’ And then I said, ‘See that picture up there? That's my dad. That's your grandpa. He's full-blooded Navajo. … You’re not Mexican, you’re Native American.’”

AI/AN traditional teachings and stories in urban Native families help to confirm identity and tribal affiliations, given that many were displaced from their tribal families during the forced relocations. Parents and young adults described family discussions about family lineage, blood quantum, and challenging tribal membership rules.

Parents also mentioned relying on extended family to reinforce AI/AN values to help prepare youth for challenges and temptations (e.g., peer pressure, AOD use). For example, “My mom always talks to my kids about tradition.” Providers suggested that teaching AI/AN stories and traditions should be encouraged in families, but there may be a need for parents and elders to teach about the meanings of AI/AN traditions so that they can contribute to understanding and healing of historical trauma and preventing AOD use: “Education on that [intergenerational trauma] is really important for understanding.”

Family Engagement in Traditional Practices

Group discussions (2 young adult, 4 parent, and 1 provider groups) described the importance of immediate and extended family members engaging together in cultural activities and traditional practices as a protective mechanism. Like storytelling, this was a way of making meaning of specific situations, but viewpoints diverged slightly. Compared to providers and young adults (3 focus groups), parents spoke noticeably more (across 4 focus groups) about the importance of families coming together to engage in traditional practices. Specifically, they described active facilitation of traditional practice and learning opportunities for their children:

“Recently my daughter had a little mythology class they have in English. So she’s like, “I have to come up with a story that is going to reflect my personality.” And I go, “Okay, I’m going to tell you. I know the Greeks did this but our people also have it” … She did write her mythology, and she looked it up, and she was like, “Oh, my gosh. This is awesome.” Like, see, it just opened that door.”

In some instances, family-centered traditional practice was perceived to provide emotional support at times of stress, as illustrated by this quote:

“What I find that helps my family, is when the healer comes to the city for us and we have that one moment, that one moment with that person, one-on-one. That is like the most ultimate thing that I can think of that actually benefits my kids, all of them. But it’s very rare, it’s like once a year.”

Family participation in traditional practices was also perceived to be helpful in strengthening mixed-heritage families, as exemplified by this parent’s story:

“Their [children’s] dad is [citizenship]. It was very important for me to include him in a lot of the activities and the pow-wows as they grew up. But I also didn’t want to push his culture away, but he became close to my family, because his family wasn’t as close.”

Although families generally encouraged engagement in traditional practices, several young adults lamented the absence of family engagement in traditional practices. Providers and parents suggested that to remedy parents’ lack of interest in or support for traditional practice, children can be encouraged to initiate and support family engagement with tradition, for example, “at GONA [where] we’ve been making these little medicine boxes for the kids to take home and to pray with and to, like, share with their families.”

Discussion

We examined risk and resilience in family dynamics among an urban AI/AN sample, with a focus on the young adult experience. The current study fills a gap in the existing literature by using qualitative data to enhance understanding of AI/AN family functioning in settings outside of reservation and tribal lands. Importantly, this qualitative approach facilitated discussions that conveyed the meanings that young adults, parents, and providers attributed to specific risks and vulnerabilities, as well as to the protective processes that foster resilience. It provides rich qualitative data on urban AI/AN families and helps further our understanding of both risk and resilience factors that may contribute to functioning, and can help formulate strategies to decrease the burden of health disparities among this population.

Many of the family-related risks discussed in focus groups support prior research in AI/AN communities [48]. Consistent with findings elsewhere, our results suggest that historical and intergenerational trauma substantially contributes to stressful and challenging family circumstances, and forces families to make meaning out of these risks and vulnerabilities [49]. Our study focuses on the perspective of urban young adults on these risks, their understanding of what drives the stresses of daily life, and what they need to feel empowered to protect themselves and their families against risk. Findings highlight the need for services to support not just young adults but also their families as they cope with trauma and its consequences [48]. Narratives about urban challenges and opportunities reinforce the case for family-centric support that empowers young adults to embrace educational, employment, and related opportunities.

Our findings emphasize the numerous mechanisms of resilience in family functioning among urban AI/AN families, including emotional and meaning adaptive systems. Family functioning has been well studied in the general population, with a focus on theory and clinical practice [50], but much of the work to date on AI/AN families has focused predominantly on risk factors, such as single-parent families, and to a lesser extent on dimensions of family functioning and resilience [51]. Much more work is needed to understand the role of resilience. Our study identified six pathways of resilience that these urban AI/AN families used to keep their families connected, including the three circles of family (immediate, extended, and communal), storytelling, and traditional practice. Emerging themes from young adult participants suggest that they can and want to become agents of family resilience, playing an active role in minimizing risks and strengthening family functioning in both practical and traditional ways. This resonates with the family resilience model and its positive adaptive mechanisms, which include finding meaning in family history, finding strength through traditional practices, emotional adaptive systems such as family cooperation, and seeking support from extended and communal families [21].

Respondents also described how they made meaning of risks and vulnerabilities through parental and family storytelling and communication, which helped them understand their history, find connection with their culture, and teach practical and moral lessons. Prior research suggests that family communication [32], and family problem-solving skills [31] are significant protective factors in urban settings for AI/AN families. Consistent with this, participants noted the importance of creating comfort within the immediate and extended family to share AI/AN traditional teachings and stories and communicate more openly about awkward or challenging topics, such as AOD use. Sharing stories, including cautionary tales and advice, seems to play a vital role in educating and disciplining adolescents and young adults. Thus, providing additional family support with storytelling, which can facilitate understanding of intergenerational trauma, could be one way to increase resilience [41]. Very few evidence-based family-based interventions exist for urban AI/AN families. However, one program, Native Drum, Dance, and Regalia (NADDAR) is a health-promoting intervention recently developed for urban AI/AN families that provides workshops on drumming, dancing, and regalia making [52]. Parenting in 2 Worlds is also a culturally grounded parenting intervention that builds on AI cultural heritage to promote AI cultural identification and involvement [53]. Clearly, there is a need for more evidence-based, culturally centered interventions and therapies for urban AI/AN families that focus on young adults.

Our current findings are noteworthy as they highlight how urban AI/AN families adapt to and negotiate challenges, especially considering numerous historical actions by the U.S. government that sought to eradicate AI/AN families and cultural ties and connections by attempting to assimilate these families within urban areas. Future interventions should focus more on strengthening these resilience pathways by capitalizing on the resilience and determination of young AI/AN adults, and the positive impact of parental involvement in enhancing their children’s AI/AN identity, parenting skills, young adults’ life skills, and preventing substance use. Furthermore, the communal family for urban AI/AN populations may be even more critical due to the coronavirus pandemic; and our recent work has shown the importance of family connection during social isolation, along with the support of community-based organizations in providing virtual traditional events and other support services [54]. Cumulatively, our findings suggest the need for federal, state, and local resources to support communities in their efforts to help families cope with trauma, learn important parenting and adult life skills, further resilience, and increase opportunities for AI/AN families to learn more about their AI/AN traditions.

Limitations

Some limitations must be noted. First, our focus group protocol did not explicitly focus on family risk and resilience. Rather, these themes emerged organically from discussions during focus groups. Because our focus groups were designed to develop a substance use intervention, the narratives we obtained about family risk and resilience might reflect more negative experiences (i.e., focus on risk rather than resilience), and narratives of resilience or positive family dynamics may be underrepresented in our study. Future investigations should draw on qualitative protocols explicitly focused on family risk and resilience in urban AI/AN people.

The aim of qualitative inquiry is to gain a richer and more in-depth accounting of a particular context: in this case, urban AI/AN family functioning. We note that the geographic scope of focus group participants (southern, central, and northern California) may not have yielded findings relevant to urban AI/AN communities across the USA. For example, making meaning out of the experience of historical trauma may differ across tribes in the USA. Additional studies should examine urban family dynamics among AI/AN individuals across the USA. Also important is that the two coders had significant previous exposure to the study population and relevant subject matter, which may have influenced our analytic framework for these data.

Finally, our study is limited by the potential for self-selection bias; i.e., those who agreed to participate may be systematically different than those who did not participate. For instance, the participants in this study may, on average, be more social, more culturally engaged, and/or have a stronger point of view than those who did not attend focus groups. In addition, while the in-person focus groups conducted at community centers proved to be an effective way to reach urban AI/AN communities, this approach may have excluded others with specific challenges (e.g., lack of transportation or time).

Conclusions

Findings for this sample of AI/AN urban individuals indicate that although families face risk, they are also resilient, and in ways that appear to differ from the general population. The different pathways through which resilience was indicated in the focus groups point to potential targets for prevention and intervention, including opportunities for greater connection to culture through learning and engaging in traditional practices, provision of more resources for community organizations serving AI/AN families, and increasing support for families, parents, and young adults in urban areas.

References

Ehlers CL, et al. Measuring historical trauma in an American Indian community sample: contributions of substance dependence, affective disorder, conduct disorder and PTSD. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;133(1):180–7.

Brave Heart MYH. The return to the sacred path: Healing the historical trauma and historical unresolved grief response among the lakota through a psychoeducational group intervention. Smith College Stud Social Work. 1998;68(3):287–305.

Cwik MF, et al. Exploration of Pathways to Binge Drinking Among American Indian Adolescents. Prev Sci. 2017;18(5):545–54.

CensusBureau. American Indian and Alaska Native Summary File; Table: PCT2; Urban and rural; Universe Total Population; Population group name: American Indian and Alaska Native alone or in combination with one or more races. US Census Bureau: Washington, D.C; 2010.

Lowe JR, Kelley MN, Hong O. Native American adolescent narrative written stories of stress. J Child Adolesc Psychiatr Nurs. 2019;32(1):16–23.

LaFromboise TD, et al. Family, community, and school influences on resilience among American Indian adolescents in the upper midwest. J Community Psychol. 2006;34(2):193–209.

Ryan SR, et al. Family functioning as a mediator of relations between family history of substance use disorder and impulsivity. Addict Disord Their Treat. 2016;15(1):17–24.

Gewirtz A, Forgatch M, Wieling E. Parenting practices as potential mechanisms for child adjustment following mass trauma. J Marital Fam Ther. 2008;34(2):177–92.

Rothbaum F, et al. Family systems theory, attachment theory, and culture. Fam Process. 2002;41(3):328–50.

Besaw A, et al. The context and meaning of family strengthening in Indian America. Cambridge: The Harvard Project on American Indian Economic Development; 2004.

Seideman RY, et al. Assessing American Indian families. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 1996;21(6):274–9.

Swaim RC, et al. American Indian adolescent drug use and socialization characteristics. J Cross Cult Psychol. 2016;24(1):53–70.

Kulis SS, et al. Parenting in 2 worlds: effects of a culturally adapted intervention for urban American Indians on parenting skills and family functioning. Prev Sci. 2016;17(6):721–31.

RedHorse JG, et al. Family behavior of urban American Indians. Social Casework. 1978;59:67–72.

Dickerson DL, et al. Community voices: integrating traditional healing services for urban American Indians/Alaska Natives in Los Angeles County, in Learning Collaborative summary report. Los Angeles: Department of Mental Health Los Angeles County; 2012.

Lobo S. Urban clan mothers: key households in cities. In: Krouse SA, Howard HA, editors. Kee** the campfires going: native Women’s activism in urban communities. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press; 2009. p. 1–21.

Friesen BJ, et al. Meeting the transition needs of urban American Indian/Alaska native youth through culturally based services. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2015;42(2):191–205.

D’Amico EJ, et al. Motivational interviewing and culture for urban Native American youth (MICUNAY): a randomized controlled trial. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2020;111:86–99.

Winek JL. Systemic family therapy: from theory to practice. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2010.

Patterson JM. Integrating family resilience and family stress theory. J Marriage Fam. 2002;64(2):349–60.

Henry CS, Sheffield Morris A, Harrist AW. Family resilience: moving into the Third Wave. Fam Relat. 2015;64(1):22–43.

McCubbin LD, McCubbin HI. Resilience in ethnic family systems: a relational theory for research and practice. In: Becvar DS, editor. Handbook of Family Resilience. New York: Springer; 2013. p. 175–95.

Burnette CE, et al. The family resilience inventory: a culturally grounded measure of current and family-of-origin protective processes in native American families. Fam Process. 2020;59(2):695–708.

Ore CE, Teufel-Shone NI, Chico-Jarillo TM. American Indian and Alaska native resilience along the life course and across generations: a literature review. Am Indian Alsk Native Ment Health Res. 2016;23(3):134–57.

Burnette CE, Figley CR. Historical oppression, resilience, and transcendence: can a holistic framework help explain violence experienced by indigenous people? Soc Work. 2017;62(1):37–44.

Haozous EA, Lee J, Soto C. Urban American Indian and Alaska native data sovereignty: ethical issues. Am Indian Alsk Native Ment Health Res. 2021;28(2):77–97.

Dickerson D, et al. Encompassing cultural contexts within scientific research methodologies in the development of health promotion interventions. Prev Sci. 2020;21(Suppl 1):33–42.

Harrist AW, et al. Family resilience: the power of rituals and routines in family adaptive systems. In: Fiese BH, editor., et al., APA handbook of contemporary family psychology: Foundations, methods, and contemporary issues across the lifespan, vol. 1. Washington: American Psychological Association Press; 2019. p. 223–39.

Wright S, et al. Holistic system of care: evidence of effectiveness. Subst Use Misuse. 2011;46(11):1420–30.

Kaholokula JK, et al. Cultural dance program improves hypertension management for native hawaiians and pacific islanders: a pilot randomized trial. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2017;4(1):35–46.

Tingey L, et al. Risk and protective factors for heavy binge alcohol use among American Indian adolescents utilizing emergency health services. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2016;42(6):715–25.

Rees C, Freng A, Winfree LT Jr. The Native American adolescent: social network structure and perceptions of alcohol induced social problems. J Youth Adolesc. 2014;43(3):405–25.

Yasui M, et al. Socialization of culture and co** with discrimination among American Indian families: examining cultural correlates of youth outcomes. J Soc Social Work Res. 2015;6(3):317–41.

Kulis S, Ayers SL, Baker T. Parenting in 2 Worlds: pilot results from a culturally adapted parenting program for urban American Indians. J Prim Prev. 2015;36(1):65–70.

Ivanich JD, et al. Pathways of adaptation: two case studies with one evidence-based substance use prevention program tailored for indigenous youth. Prev Sci. 2020;21(Suppl 1):43–53.

Garrett JT, Garrett MW. The path of good medicine: understanding and counseling Native American Indians. J Multicult Couns Dev. 1994;22(3):134–44.

Davis B, Dionne R, Fortin M. Parenting across cultures. In: Selin H, editor. Science across cultures: the history of non-western science. Berlin: Springer; 2014. p. 367–77.

Ayers SL, Kulis S, Tsethlikai M. Assessing parenting and family functioning measures for urban American Indians. J Community Psychol. 2017;45(2):230–49.

Whitbeck LB. Primary socialization theory: it all begins with the family. Subst Use Misuse. 1999;34(7):1025–32.

Oetting ER, Donnermeyer JF. Primary socialization theory: the etiology of drug use and deviance. I. Subst Use Misuse. 1998;33(4):995–1026.

Johnson CL. An innovative healing model: empowering urban native Americans. In: Witko TM, editor. Mental health care for urban indians: clinical insights from native practitioners. Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association; 2006.

D’Amico EJ, et al. Integrating traditional practices and social network visualization to prevent substance use: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial among urban Native American emerging adults. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2021;16(1):56.

Dickerson DL, et al. Integrating motivational interviewing and traditional practices to address alcohol and drug use among urban American Indian/Alaska native youth. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2016;65:26–35.

Dedoose. Web application formanaging, analyzing, and presenting qualitative and mixed method research data. Los Angeles: SocioCultural Research Consultants; 2019.

Ryan GW, Bernard HR. Techniques to identify themes. Field Meth. 2003;15:85–109.

Maxwell JA. Using numbers in qualitative research. Qual Inq. 2010;16(6):475–82.

Cohen J. A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educ Psychol Measur. 1960;20:37–46.

Nutton J, Fast E. Historical trauma, substance use, and indigenous peoples: seven generations of harm from a “big event.” Subst Use Misuse. 2015;50(7):839–47.

Gibbs A, et al. Associations between poverty, mental health and substance use, gender power, and intimate partner violence amongst young (18–30) women and men in urban informal settlements in South Africa: a cross-sectional study and structural equation model. PLoS One. 2018;13(10):e0204956.

Miller IW, et al. The McMaster approach to families: theory, assess- ment, treatment and research. J Fam Ther. 2000;22:168–89.

Cheadle JE, Whitbeck LB. Alcohol use trajectories and problem drinking over the course of adolescence: a study of north american indigenous youth and their caretakers. J Health Soc Behav. 2011;52(2):228–45.

Johnson CL, Begay C, Dickerson DL. Final Development of the Native American Drum, Dance, and Regalia Program (NADDAR), a behavioral intervention utilizing traditional practices for urban native american families: a focus group study. Behav Therap. 2021;44(4):198–203.

Kulis SS, et al. Parenting in 2 worlds: Effects of a culturally grounded parenting intervention for urban American Indians on participant cultural engagement. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2020;26(4):437–46.

D’Amico EJ, et al. Examining Risk and resilience factors in urban, American Indian/Alaska native youth during the coronavirus pandemic. Am Indian Cult Res J. 2020;44(2):21–48.

Acknowledgements

We thank Jennifer Parker, Keisha McDonald, and the RAND Survey Research Group for their help with this study. We also want to thank the reviewers for their constructive and extremely helpful comments during the peer review process.

Funding

This research leading to these results received funding from the National Institutes of Health through the NIH HEAL Initiative under award number UG3DA050235; PIs: D’Amico and Dickerson.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Alina I. Palimaru, PhD MPP: data collection; formal qualitative analysis; investigation; writing original draft; review and editing.

Ryan A. Brown, PhD: data collection; formal qualitative analysis; investigation; writing original draft; review and editing.

Virginia Arvizu-Sanchez: review and editing.

Lynette Mike: review and editing.

Kathleen Etz, PhD: investigation; review and editing.

Carrie L. Johnson, PhD: project administration; investigation; review and editing.

Daniel L. Dickerson, DO MPH: conceptualization; data curation; funding acquisition; project administration; supervision; investigation; review and editing.

Elizabeth J. D’Amico, PhD MA: conceptualization; data curation; funding acquisition; project administration; supervision; investigation; review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the RAND Corporation (No. IRB00000051).

Consent to Participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or its NIH HEAL Initiative.

The views and opinions expressed in this manuscript are those of the author only and do not necessarily represent the views, official policy, or position of the US Department of Health and Human Services or any of its affiliated institutions or agencies. No portion of this work has been previously presented or disseminated. This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health through the NIH HEAL Initiative under award number UG3DA050235; PIs: D’Amico and Dickerson.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Palimaru, A.I., Brown, R.A., Arvizu-Sanchez, V. et al. Risk and Resilience Among Families in Urban AI/AN Communities: the Role of Young Adults. J. Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 10, 509–520 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-022-01240-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-022-01240-7