Abstract

Introduction

The use of optical coherence tomography (OCT) images is increasing in the medical treatment of age-related macular degeneration (AMD), and thus, the amount of data requiring analysis is increasing. Advances in machine-learning techniques may facilitate processing of large amounts of medical image data. Among deep-learning methods, convolution neural networks (CNNs) show superior image recognition ability. This study aimed to build deep-learning models that could distinguish AMD from healthy OCT scans and to distinguish AMD with and without exudative changes without using a segmentation algorithm.

Methods

This was a cross-sectional observational clinical study. A total of 1621 spectral domain (SD)-OCT images of patients with AMD and a healthy control group were studied. The first CNN model was trained and validated using 1382 AMD images and 239 normal images. The second transfer-learning model was trained and validated with 721 AMD images with exudative changes and 661 AMD images without any exudate. The attention area of the CNN was described as a heat map by class activation map** (CAM). In the second model, which classified images into AMD with or without exudative changes, we compared the learning stabilization of models using or not using transfer learning.

Results

Using the first CNN model, we could classify AMD and normal OCT images with 100% sensitivity, 91.8% specificity, and 99.0% accuracy. In the second, transfer-learning model, we could classify AMD as having or not having exudative changes, with 98.4% sensitivity, 88.3% specificity, and 93.9% accuracy. CAM successfully described the heat-map area on the OCT images. Including the transfer-learning model in the second model resulted in faster stabilization than when the transfer-learning model was not included.

Conclusion

Two computational deep-learning models were developed and evaluated here; both models showed good performance. Automation of the interpretation process by using deep-learning models can save time and improve efficiency.

Trial Registration

No15073.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is the leading cause of severe visual loss, and the number of patients with this condition is increasing with the rapid aging of the population in developed countries [1]. The 10-year cumulative incidence of AMD was reported to be 12.1% in the Beaver Dam Study in the United States and 14.1% in the Blue Mountains Eye Study in Australia [2, 3]. AMD is categorized into dry and wet AMD, based on the absence or presence of neovascularization [4]. In wet AMD, fluid leakage or bleeding from the permeable capillary network in the sub-retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) and fibrotic scars in the subretinal areas result in severe photoreceptor degeneration [5]. Several recent large clinical trials have shown the effectiveness of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) therapy (ranibizumab, bevacizumab, and aflibercept) for neovascular AMD [6,7,8,9,10]. However, follow-up studies of these trials have also reported that retaining good visual acuity for a long period of time in real practice was difficult, indicating that monthly monitoring of patients receiving anti-VEGF treatment requires much effort from patients and medical staff, and increases medical costs [11].

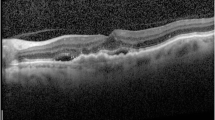

Spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) is a commercially available device that clearly describes particular findings of AMD, such as drusen, intra-retinal fluid (IRF), sub-retinal fluid (SRF), sub-retinal hyper-reflective material, including hemorrhage and retinal pigment epithelium detachment, etc. [12]. Among these, exudative changes (intra- and sub-retinal fluid and hemorrhage) are the key indication for most physicians to initiate anti-VEGF therapy and evaluate the therapeutic effect [13]. Zero tolerance has been applied for the large clinical trial mentioned above [14]. Therefore, the amount of OCT data requiring analysis is increasing, beyond clinical capacity [15].

Advances in machine-learning techniques provide a solution for meaningful interpretation of large amounts of medical image data arising from the frequent treatment and follow-up monitoring of patients [16]. In particular, convolution neural networks (CNNs) have greatly advanced the classification of medical images using multi-layer neural networks and deep-learning algorithms [17]. In ophthalmology, the excellent accuracy of CNNs has already been reported in the classification of diabetic retinopathy from fundus photographs, visual field examination of glaucoma patients, grading of pediatric nuclear cataracts, etc. [18,19,20]. The impressive performance of neural networks in the classification of AMD images has also been reported for the automated detection of AMD features in OCT and fundus photographs, for guidance of anti-VEGF therapy, and monitoring disease progression [18, 21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28]. Although some studies have classified the exudative feature of AMD for automated segmentation [21, 29], to our knowledge, there are no reports about the classification of exudative change with AMD in deep learning models without segmentation.

The purpose of the present study was to build two deep-learning models and to evaluate their performance without using a segmentation algorithm. The first CNN model was built to distinguish AMD eyes from healthy eyes on OCT scans, and the second transfer-learning model was used to distinguish between AMD with and without exudative changes.

Methods

This research was conducted in line with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964, and the research protocols and their implementation were approved by the Ethics Committee of Kobe City Medical Center General Hospital (approval date; Sept. 17, 2015 and approval number: No15073). The committee waived the requirement for obtaining informed consent given that this was a retrospective observational study of medical records, and retrospectively registered.

We included the records of patients who visited Kobe City Medical Center General Hospital from March 2016 to November 2017. We included SD-OCT (Heidelberg Spectralis, Heidelberg Engineering, Heidelberg, Germany) images of normal subjects and of patients with AMD.

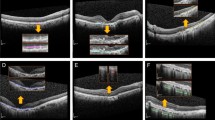

The outline we have researched is as follows (Fig. 1). We built two classification models. In the first CNN model, we classified images into normal and AMD images. In the second transfer-learning model, we classified AMD images into those with and those without exudative changes. We used class activation map** (CAM) as a heat map to show the location of the images that the CNN models emphasized in the classification. Additionally, in the second model, we compared the speed of learning stability with the model using transfer learning and the single CNN model.

We built two classification models. In the first CNN model, we classified images into normal and AMD images. In the second transfer-learning model, we classified AMD images into those with and those without exudative changes. We used CAM to show the location of the image that CNN models emphasized in the classification as the heat map. Additionally, in the second model, we compared the speed of learning stability with the model using transfer learning and the single CNN model. AMD age-related macular degeneration, CNN convolution neural network, CAM class activation map**

Patients diagnosed with AMD and normal control subjects were enrolled at the outpatients’ clinic during the same period. AMD was diagnosed by means of fundus examinations, fluorescein angiography/indocyanine green angiography, and OCT images by independent retinal specialists. Only one eye per patient was selected for analysis. The exclusion criteria were poor image quality and the presence of other potentially confounding retinal pathologies.

We included 120 eyes of 120 AMD patients, and 49 eyes from 49 normal subjects, as the training data group, and 77 eyes of 77 AMD patients, and 25 eyes from 25 normal subjects, as the test data group. We used OCT images for training and validating deep-learning models. In the first model, 185 normal images and 1049 AMD images were used for training data, and the CNN model was subsequently evaluated using another 49 normal images and 333 AMD images. In the second model, 535 AMD images with exudative changes and 514 AMD images without exudative changes were selected as training data, and the second model was subsequently evaluated using another 188 images with exudative changes and 154 images without exudative changes.

Building the Models

We built two classification models. In the first CNN model, we classified images into normal and AMD images. In the second transfer-learning model, we classified AMD images into those with and those without exudative changes (Fig. 1).

The process of image classification is summarized in Fig. 2. The CNN classification models were constructed using a cropped image obtained by dividing the original image into three in order not to degrade the image quality. After classifying the cropped images with the CNN models, three cropped images were reassembled into the original image to determine the original image classification.

a CNN classification models were constructed using a cropped image obtained by dividing the original image into three in order not to degrade the image quality. b After classifying the cropped images with CNN models, the three cropped OCT images were returned to the original image to determine the original image classification. If at least one of the three cropped OCT images showed AMD findings, the original image was judged as AMD, and it was judged as normal only if all three cropped images were without AMD findings. The second judgement of the presence of exudative fluid was similarly performed. CNN convolution neural network, OCT optical coherence tomography, AMD age-related macular degeneration

SD-OCT images obtained with either a radial-scan (scan length: 6.0 mm) or cross-scan (scan length: 9.0 mm) protocol were included. In the cross-scan image, the central 6.0-mm area was cropped to obtain the same scan length as radial scans and resized to 496 × 496 pixels.

Considering (0,0) as the bottom-left corner of an OCT image, and the left-to-right as the x-axis direction and top-to-bottom as the y-axis direction, 3 points for which y was on the RPE line were determined automatically, with a fixed value of x as 112, 247, or 399. With these points as centers, we cropped three images from each OCT image to a size of 224 × 224 pixels to increase the numbers in the data set without resizing images.

Three ophthalmologists (N. M., M. M, Y. H.) who have extensive experience with macular outpatients independently labeled the three cropped images. In the first model, labelling the images as “normal” or “AMD” was conducted in two steps. First, each cropped image was labeled as “without AMD finding” and “with AMD finding,” depending on whether the image contained any AMD findings, such as drusen, pseudo-drusen, pigmented epithelial detachment (PED), drusenoid PED, geographic atrophy, hyperreflective foci, or sub-retinal hyper-reflective material. Only images in which the three physician’s diagnoses matched were included in the next step. Original images were judged as “normal” when all three images were labeled as “without AMD finding” and judged as “AMD” only when at least one of the three images was labeled as “with AMD finding.”

In the second model, we cropped three images from the AMD OCT images, as in the first model. We then labeled these images as “exudative change = fluid” or “without exudative change = no fluid” in two steps. First, each cropped image was labeled as “with fluid finding” and “without any fluid finding,” depending on whether the image contained any fluid, such as exudative changes (intra- and sub-retinal fluid and hemorrhage), as judged independently by the same three well-trained ophthalmologists. Only the images for which the three physicians reached agreement were included in the next step. Original images were then categorized as “without exudative change = no fluid” when all three images were labeled as “without any fluid finding,” and were categorized as “exudative change = fluid” only when there was at least one of the three images that was labeled as “with fluid finding.”

The number of images was expanded about 1000 times with flips, translations, or rotations. A batch size of 32 images and an epoch number of 1000 times was used during the training phase, using an optimization function of the Adam algorithm. Finally, from 1000 CNN models, we selected the one with the highest area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC). In this study, a system running Ubuntu 16.04 OS, and with a single GTX 1080 TI graphics card (Nvidia, Santa Clara, CA, USA), was used.

We examined the AUROC to assess the performance of the CNN models for classification of the cropped images. In order to classify the original image, the cropped images were recombined, and the sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of the classification models were determined.

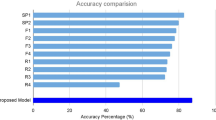

Furthermore, we compared the necessary number of epochs for the training loss to converge, and classification performance, between the transfer-learning model and the CNN of the same architecture without transfer learning. To build a robust classification model, the data augmentation and dropout technique were also applied in the training phase for both models.

CNN Model Architecture

We applied a deep-learning model using CNNs for use in our classification system (Table 1). Two classification models were built. We arranged convolutional layers as layer 1, 2, 4, 5, 7, 8, 10, 12, and 14 for the activation functions of rectified linear units (ReLU) and batch normalization next to convolutional layers [29, 30]. We arranged max. pooling layers as layers 3, 6, 9, 11, and 13 after convolutional layers. The global average pooling layer was layer 15. We set the dropout layer (drop rate: 0.2) as layer 16 and the fully connected layers as layers 16 and 17. Finally, in the final output layer, we arranged layer 18 as the softmax layer. This CNN architecture was applied to both models. Transfer learning was used to retrain a CNN that had previously been constructed, and most unit weights were pretrained.

Heatmap Creation

One method that represents the area of the CNN classification model on a heatmap is class activation map** (CAM); this technique was applicable in our case, as a global average pooling layer was used in our proposed CNN architecture. Using this technique, heat maps were generated for each model. For the first model, we generated a heat map for the AMD category, indicating the effective region for the model to identify AMD, while for the second model, a heat map was created for the discriminative region used to identifying AMD with or without the presence of fluid [Full size image

Comparison of the necessary number of epochs for convergence of the training loss, and classification performance, between the transfer-learning model and the CNN of the same architecture without transfer learning. In the second model, for classification of AMD images into with or without exudative changes, learning stabilized faster when using transfer learning. CNN convolution neural network, AMD age-related macular degeneration, AUROC area under the receiver operating characteristic curve