Abstract

Introduction

The efficacy of stiripentol in Dravet syndrome children was evidenced in two randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 studies, namely STICLO France (October 1996–August 1998) and STICLO Italy (April 1999–October 2000), but data were not fully exploited at the time.

Methods

This post-hoc analysis used additional information, notably collected during the open-label extension (OLE) month, or reported by caregivers in individual diaries, to evaluate new outcomes.

Results

Overall, 64 patients were included (31 in the placebo group, 33 in the stiripentol group) of whom 34 (53.1%) were female. Patients’ mean and median (25%; 75%) age were 9.2 years (range 3.0–20.7 years) and 8.7 years (6.0; 12.1) respectively. At the end of the double-blind treatment period, 72% of the patients in the stiripentol group had a ≥ 50% decrease in generalized tonic–clonic seizure (GTCS) frequency, versus 7% in the placebo group (P < 0.001), 56% had a profound (≥ 75%) decrease versus 3% in the placebo group (P < 0.001), and 38% were free of GTCS, but none in the placebo group (P < 0.001). The onset of stiripentol efficacy was rapid, significant from the fourth day of treatment onwards. The median longest period of consecutive days with no GTCS was 32 days in the stiripentol group compared to 8.5 days in the placebo group (P < 0.001). Further to the switch to the third month OLE, an 80.2% decrease in seizure frequency from baseline was observed in patients previously receiving placebo, while no change in efficacy was observed in those already on stiripentol. Adverse events were more frequent in the stiripentol group, with significantly more episodes of somnolence, anorexia, and weight decrease than in the placebo group.

Conclusion

Altogether these new analyses of the STICLO data reinforce the evidence for a remarkable efficacy of stiripentol in Dravet syndrome, with a demonstrated rapid onset of action and sustained response, as also evidenced in further post-randomized trials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this study? |

Two randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 studies demonstrated the efficacy of stiripentol in patients with Dravet syndrome. |

As data were not fully exploited at the time, this post-hoc analysis aimed to evaluate additional efficacy criteria and new relevant outcomes. |

What was learned from the study? |

A rapid antiseizure efficacy of stiripentol in patients with Dravet syndrome was demonstrated, with highly significant responder rates and long seizure-free periods. |

This marked efficacy together with an acceptable tolerability likely translates into improvements in patients and caregivers’ quality of life. |

Introduction

Dravet Syndrome (DS) [1] is a rare and severe Developmental and Epileptic Encephalopathy (DEE). Patients typically have highly pharmaco-resistant convulsive seizures from the first year of life, mostly generalized clonic or tonic–clonic seizures (GTCS), and likely long-lasting in duration, thus resulting in status epilepticus (SE), especially in infancy and middle childhood [2,3,4,5]. GTCS in DS negatively interfere with further development, strongly impact both patients’ and caregivers’ quality of life and can be life threatening [4, 6, 7].

The initial signal of stiripentol (STP) effect in DS was discovered in the mid-1990s, in a French prospective exploratory (“basket”) phase 2 study [8]. At that time, the role of the SCN1A gene was still unknown, the aggravating effects of sodium channel blockers such as carbamazepine and lamotrigine were just emerging [9], and the combination of valproate and clobazam was the standard of care antiseizure medication. Pharmacological interactions between these two drugs and stiripentol were already known [8].

Afterwards two pivotal phase 3 trials, the STICLO studies, comparing STP with placebo as an adjunctive therapy to valproate (maximum dose 30 mg/kg/day) and clobazam (maximum dose 0.5 mg/kg/day) comedication, were initiated in France and Italy. Based on a similar randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, design, the STICLO studies evaluated the efficacy of a 2-month STP therapy at 50 mg/kg/day on GTCS; then, patients were proposed to enter an additional 1-month open-label extension (OLE) period. Both studies clearly demonstrated STP efficacy [10, 11] and served as the basis for marketing authorization for STP in DS—the very first one in a DEE—in Europe (2007), in Japan and Canada (2012), and in the US (2018). Since then, the efficacy of stiripentol has been confirmed in numerous prospective and retrospective real-world evidence studies worldwide [12,13,14,15], and more than 56,759 patient-year with DS and, with off-label prescriptions, other forms of severe epilepsies have benefited from this treatment as of October 31, 2022 [16].

Some data from the STICLO trials were not published in extenso at the time, notably the detailed efficacy results of STICLO Italy and data from the OLE period. Also, since the STICLO studies, new relevant outcomes have now emerged in the field of drug trials, as evidenced by the two treatments recently approved in DS, cannabidiol (2018) and fenfluramine (2020). The objective of the present report is to conduct a post-hoc analysis of data from both Phase 3 STICLO studies, which includes the rate of patients with ≥ 75% decrease in seizure frequency, the number of convulsive seizure-free days, and the time to onset of STP efficacy, all these parameters having significant impact on patients and caregivers’ quality of life.

Methods

Study Design and Patients

STICLO studies were conducted with similar protocols and performed at multiple centers in France from October 1996 to August 1998, and in Italy from April 1999 to October 2000. Inclusion of patients diagnosed as DS was made according to the clinical criteria established by Dravet [17], i.e., onset of epilepsy in the first year of life with generalized clonic (or tonic–clonic) seizures, normal psychomotor development and normal electroencephalogram (EEG) before seizure onset, and, after 1 year of age, occurrence of atypical absences and myoclonia, generalized spikes and waves on EEG, and slowing of psychomotor development. Patients were aged between 3 and 18 years and had to have experienced at least four GTCS a month despite optimized therapy with valproate and clobazam. Patients receiving other drugs (except diazepam as a rescue medication and progabide), and those whose parents were unable to comply regularly with drug delivery and daily seizure diary, were excluded. According to local regulations, the design and conduct of the STICLO studies were approved by the Ethics Committee of the coordinating center in France, and by the Ethics Committees of each center in Italy. Written informed consent was obtained from the parents or guardian of all patients. Both studies were performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and its later amendments, Good Clinical Practices, and according to the local regulatory requirements.

After a 1-month baseline period, patients who continued to have at least 4 GTCS per month were randomly assigned to receive placebo or stiripentol at the dose of 50 mg/kg/day (maximum dose of 3000 mg/day) with no titration. Study treatment was given twice or three times daily, added on to valproate and clobazam during the 2-month double-blind period. To minimize adverse effects, the maximum dose of valproate was limited to 30 mg/kg/day and that of clobazam to 0.5 mg/kg/day. Doses could be decreased by 10 mg/kg/day for valproate in cases of loss of appetite and by 25% for clobazam in cases of drowsiness or hyperexcitability.

After the 2-month double-blind period, patients were allowed to enter an additional 1-month open-label extension period where they all received STP, with the blind maintained on treatment previously received (Figure S1). Patients who benefited from stiripentol treatment were then allowed to enter an open-label observational long-term follow-up study, followed by a temporary authorization for stiripentol use.

Outcome Measures

In both studies, response to treatment was defined by the reduction in the number of convulsive seizures compared to baseline. Response rate was calculated based on the decrease in monthly GTCS frequency, and it was considered as clinically meaningful (≥ 50% reduction), profound (≥ 75% reduction), or as seizure freedom (= 100% reduction).

Study investigators reported seizure frequency monthly by using the diary completed by parents and caregivers. In the present analysis, data from the diaries were entered for the first time and the seizure occurrence was captured daily, allowing the evaluation of additional parameters, such as the total number of seizure-free days and the longest period of consecutive days free of seizures. All types of seizures were reported in the diaries, but only GTCS were taken into account for the assessment of treatment efficacy, since these are the most disabling seizure types, are observed in all patients, and are easily identified. Conversely, counting other types of seizures, such as absence seizures or myoclonus, is less reliable and difficult to obtain.

At the end of the OLE period, investigators completed a specific follow-up form where they reported information regarding STP dosage, seizure frequency, and adverse events, if any. When available, data from the follow-up forms were captured for the present analysis.

Statistical Analyses

Data poolabilty from both STICLO-France and STICLO-Italy studies was assessed based on the demographic data and the primary endpoint results using t tests and chi-squared tests (Type I Error rate of 0.10). Studies were considered poolable if the data from the two studies were not statistically significantly different.

Baseline characteristics and seizure frequency were reported by treatment groups with numbers and proportions for categorical variables, as well as mean standard deviation and the range of values for continuous variables. Seizure frequencies were adjusted for 30-day period to compare the corresponding frequencies. Percentage changes in seizure frequency was also represented on an individual basis by a waterfall chart, where patients were ordered by the magnitude of the change between baseline and 1st month under treatment, 2nd month under treatment, or OLE period.

Responder rates were reported by treatment group at 1-month, 2-month, and 3-month OLE. Considering the small sample sizes, confidence intervals at 95% (CI95%) were computed by the Wilson method with continuity correction [18]. In addition, the mean percentage change and CI95% from baseline in seizure frequency, and the cumulative proportion of responders as a function of the percentage reduction in the number of seizures, were shown graphically for each treatment group. A Sankey diagram was also used to describe and analyze longitudinal patient data during treatment period and OLE period.

Regarding patients’ diaries, the total number of seizure-free days was calculated and was adjusted for a 60-day period to make the 2-month double-blind period comparable between patients. Three patients with missing data from diaries during the 2-month treatment period were excluded. The longest period of consecutive seizure-free days during the double-blind period was also determined. A conservative approach was used as patients with missing diaries were not excluded and the interval was stopped if data were missing.

Moreover, a time-to-onset analysis was conducted using negative binomial regressions to model the cumulative number of seizures by treatment group during the follow-up from day 1 to day 30. Models were estimated to test the hypothesis that mean cumulative number of seizures is not different between the placebo and the STP group. At day n, the cumulative number of seizures from day 1 to day n during the treatment period were modeled by an intercept, the treatment group effect, and adjusted on the corresponding cumulative number of seizures from day 1 to day n during the baseline period. Logarithm of the period (n days) was added as an offset term. Least squares (LS) mean number of seizures count for STP and placebo groups were reported for each day n and ratios of LS means were tested to see if they were significantly different from 1. LS means and CI95% were reported graphically for each day and treatment group.

Results

STICLO France and STICLO Italy Individual Results

Detailed efficacy outcomes of the individual STICLO France and STICLO Italy studies are reported in Table 1. Both studies found similar results that clearly demonstrated STP efficacy. In STICLO France, the reduction in seizure frequency was greater on STP than on placebo (− 62% and + 12%, respectively; P < 0.0001), with significantly more patients having a clinically meaningful response (≥ 50% reduction in seizure frequency) (71% vs. 5%; P < 0.0001). Also, 9 patients were free of GTCS in the STP group but none in the placebo (P = 0.0013). The results of STICLO Italy were similar, with greater reduction in seizures (− 74% vs. − 13%; P = 0.0018) and more responders at 50% (67% vs. 9%; P = 0.0094). Three patients were free of GTCS in the STP group but none in the placebo.

In both studies, adverse events were more frequent in the STP group, and mainly involved the nervous system, such as drowsiness, hyperexcitability, and agitation, or the gastro-intestinal system, such as loss of appetite, weight loss, or weight gain.

Results of the Pooled STICLO Studies

Statistical tests performed on the demographic and primary endpoints of STICLO France (n = 41) and STICLO Italy (n = 23) studies confirmed data poolability. This resulted in a total of 64 patients with available data, and additional information from the open label period was available for 44 patients (69%).

At baseline, the placebo and STP groups were similar for demographic characteristics, medical history, and mean doses of concomitant antiseizure medications (Table 2). Mean number of generalized tonic–clonic or clonic seizures was high in both groups (21.7 ± 21.8 in the placebo group and 23.6 ± 22.8 in the STP group) despite optimized therapy with valproate and clobazam.

At the end of the first month of the double-blind treatment period, a marked and significant efficacy of STP was observed over placebo. Mean percent change in seizure frequency from baseline was − 85% in the STP group versus + 10% in the placebo group (P < 0.001) (Table 3). The proportions of patients who experienced a meaningful (≥ 50% reduction), profound (≥ 75% reduction), or seizure freedom (= 100% reduction) were 91%, 79%, and 48%, respectively in the STP group compared to 13%, 3%, and 0% in the placebo group (P < 0.001 in each case) (Table 3; Fig. 1). On an individual basis, during this first month, all patients from the STP group experienced a decrease in seizure frequency compared to baseline, while, in the placebo group, only 15 out of 31 patients had a lower frequency compared to baseline (Figure S2). Regarding time-to-onset of efficacy, a significant and maintained difference was demonstrated between the groups from day 4 onwards (P = 0.018) (Fig. 2).

At the end of the 2-month double-blind treatment period, mean percent change in seizure frequency from baseline was − 66% in the STP group versus + 4% in the placebo group (P < 0.001) (Table 3). In accordance with recommendations [19], the primary efficacy endpoint of the STICLO trials was the responder rate, defined as a ≥ 50% decrease in convulsive seizures. Stiripentol demonstrated a clear superiority over placebo as 72% of the patients were responder in the STP group versus 7% in the placebo group (P < 0.001) (Table 3; Fig. 1). When considering patients with a profound (≥ 75%) decrease in convulsive seizures, STP was again highly superior to placebo with 56% of the patients on STP responders versus 3% in the placebo group (p < 0.001). After 2 months of treatment, 38% of the patients on STP were free of GTCS, but none in the placebo group (P < 0.001) (Table 3; Fig. 1). On an individual basis, during the second month only 3 patients on STP had a higher seizure frequency compared to baseline, while, in the placebo group, similarly to the first month period, only 50% of the patients had a decreased seizure frequency compared to baseline (Figure S2).

Further to the switch to the OLE period, efficacy was maintained in patients from the STP group during the extra third month of treatment. Mean percent change in seizure frequency from baseline was − 62.3%, similar to the 66% decrease observed at the end of the double-blind treatment period (Table 3). Conversely, a dramatic decrease in seizure frequency was observed in patients previously receiving placebo (Fig. 3), with a mean percent change in seizure frequency from baseline of − 80.2% (Table 3). At the end of the OLE, no difference was found between the two treatment groups, neither regarding the mean percent change in seizure frequency from baseline (P = 0.5) nor in the responder rates (P = 0.45, P = 0.531, and P = 1 for ≥ 50%, ≥ 75%, and = 100% decrease in seizure frequency, respectively) (Table 3; Figs. 1,3). On an individual basis, all patients who switched from placebo to STP during the OLE had a decrease in seizure frequency, while only 3 patients who continued STP had a higher seizure frequency compared to baseline, similarly to the end of the second month treatment period (Figure S2).

Evolution of the mean percent change of seizure frequency. The mean change in seizure number is represented for each treatment group at the end of the 1st and 2nd months and at the end of the open-label period. Error bars represent the 95% confidence interval of the percent change in seizure frequency at each visit

The longitudinal individual treatment response over time visualized on a Sankey diagram confirmed STP efficacy and the maintenance of the effect over the 3-month period (Figure S3). In the STP group, 64% of the patients who were seizure-free at the end of the double-blind period remained so during the OLE. While some patients who were responders at month 1 and/or month 2 became non-responders during the OLE, 5 patients who were not responders at month 2 became responders during the OLE. Notably, 2 had a ≥ 50% decrease in seizure frequency compared to baseline, 1 had a ≥ 75% decrease, and 2 were seizure-free.

New data based on diaries were collected for 52 patients (81%), and the number of seizure-free days/60-day period and the longest period of consecutive days free of seizures during the double-blind treatment period were reported in the treatment group (Table 4; Fig. 4). There was a median number of 55.8 seizure-free days/60-day period in the STP group compared to 40.9 in the placebo group (P < 0.001) (Table 4). The median longest period of consecutive seizure-free days was 32 days in the STP group and 8.5 days in the placebo group (P < 0.001) (Fig. 4).

Individual maximum number of consecutive seizure-free days. Each patient from placebo and stiripentol groups is represented with the corresponding longest interval of consecutive seizure-free days during the 2-month double-blind treatment period. Intervals that continued until the end of follow-up are marked with an asterisk

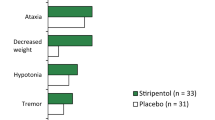

Adverse events were more frequent in the STP group (100% of patients presented at least one) than in the placebo group (45%). The most common adverse events across STICLO trials are presented in Table 5. Overall, the incidence of somnolence, anorexia, and weight decrease was significantly higher in STP than in the placebo group. Also, during the double-blind period, serious adverse events were reported in 2 patients in the STP group: one patient experienced an episode of SE, while an episode of giant urticaria (allergic dermatitis) was reported in a second patient, for whom treatment was suspended and then resumed uneventfully. In the placebo group serious adverse events were reported in 3 patients, consisting of somnolence and motor dysfunction involving the right half of the body, SE, and repeated seizures.

Discussion

These new, more comprehensive analyses of the STICLO data reinforce and complete the evidence for a marked efficacy of STP in Dravet syndrome. STP demonstrated a clear superiority over placebo, not only in the ≥ 50% decrease in convulsive seizures but also considering patients with a profound (≥ 75%) reduction in seizure frequency, and the number of patients seizure-free. These results also highlight the rapid onset of STP efficacy, detectable from the fourth day of treatment, and its maintenance during the OLE period. Importantly, longitudinal data evidenced that patients who do not respond initially can achieve a significant seizure reduction and become responder after 3 months of treatment. Finally, both the number or seizure-free days and the longest period of consecutive seizure-free days were significantly higher in the STP group. Beyond the seizures themselves, all these parameters are of critical importance for the child's quality of life and cognitive functioning.

The STICLO France study was the first-ever double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, that evaluated the efficacy of an antiseizure medication in Dravet syndrome. As no data were available in a reference population with the same type of epilepsy, the statistical analysis plan stated that a difference in percentage of responders of at least 25% was required between STP and placebo, and that an interim analysis without unblinding would be done after 20 patients in each group were enrolled. At the time of this interim analysis, in cases of significant difference between the two groups (at the reduced degree of significance, α′ = 2.5%), the study would be terminated; otherwise, it would continue up to a maximum of 100 patients. The interim analysis, performed as planned on 41 evaluable patients, showed a CI95% true difference between 42.2% and 85.7%, thus demonstrating a significant superiority of STP over placebo. Therefore, recommendation was made to stop the study as it had already met the primary efficacy criterion with 20 patients in the placebo group and 21 in the stiripentol group.

In the subsequent STICLO Italy study, the number of patients to be enrolled was extrapolated from STICLO France efficacy results, and it was determined that 20 patients (10 in each treatment group) would suffice to demonstrate a significant difference. Accordingly, 23 patients were enrolled, 12 on STP (mean dose 51.1 mg/kg/day) and 11 on placebo. STICLO trials followed a rigorous methodology, leading to approval of stiripentol for DS in Europe in 2007, then in 2018 in the US after both were validated by an FDA audit in 2016. Their originality lies in the limited number of patients needed that were thoroughly characterized, allowing the exposure of as few children as possible to the trial condition while preserving its quality. This approach praised by the community for “how best to serve children” [20], paved the way for robust trials that seemed impossible until then for rare pediatric diseases.

Pooled data from the two STICLO studies are presented here for the first time. Although meta-analyses were published previously, they only included partial data, notably for STICLO Italy [21,22,23]. Efficacy results of the STICLO Italy are presented extensively here, together with efficacy criteria that were not detailed at the time the studies were conducted. Notably, similarly to the seizure reduction thresholds used for recently approved Dravet syndrome medications [24, 25], the rate of profoundly responder patients was calculated. At the end of the 2-month double-blind treatment period, 56% of the patients on STP experienced a profound (≥ 75%) decrease in convulsive seizures versus 3% of those on placebo. This observation, in line with the high number of patients on STP who were free of convulsive seizures, supports a high efficacy of this drug in DS. Moreover, a reduction in monthly convulsive seizure frequency is associated with clinically meaningful levels of improvement in everyday executive functions in these patients [26].

The analysis of the time-to-onset to efficacy evidenced a significant and permanent difference in favor of STP with respect to placebo from day 4, which was maintained afterwards. This rapid effect is clinically important given the severity of DS, notably in young patients who are more likely to experience long-lasting seizures often evolving into SE, considering its negative impact on immediate mortality and long-term outcome [14, 27].

Dravet syndrome imposes a considerable burden on patients’ and caregivers’ quality of life [4, 6, 7]. Recently, the number of seizure-free days was proposed as a marker of patient and caregiver quality of life [28,29,30], and it was estimated that each additional patient–seizure-free days increased utility by 0.005, and that increasing seizure-free days per 28 days was a significant predictor of improved quality of life [30]. In the STICLO studies, both the total number of seizure-free days and the maximum number of consecutive seizure-free days were significantly higher in the STP group than in the placebo group (P < 0.001 in both cases). Despite no validated scales being applied, this result may indicate that STP could improve patients’ and caregivers’ quality of life by decreasing the burden of seizures and their consequences. This observation is in line with a recent report [15] which showed that initiating STP in infants with DS significantly reduced long-lasting seizures, including SE, and hospitalizations in the critical first years of life.

From a safety perspective, side effects often led to decrease comedication doses (in 17 patients) as planned by the protocol, attenuating adverse events in all these patients. This observation is in accordance with the Stiripentol Summary of Product Characteristics, in which it is indicated that many of the adverse reactions are often due to an increase in plasma levels of associated anticonvulsant medicinal products and may regress when their dose is reduced.

As diaries or follow-up forms were missing for some patients, the amount of data available for analyses during the OLE period was incomplete. Also, patients and physicians were aware of the treatment administered during the OLE period, making the analyses less robust with respect to the double-blind period. Despite these caveats, efficacy and safety results in the OLE period are fully aligned with those collected at months 1 and 2, altogether corroborating STP efficacy. Follow-up data were not collected further except in the Paris center (STICLO France) [11]: among the 16 patients included, 12 were still on STP in adulthood. They were satisfactorily controlled with good tolerability 26–28 years later, as recently reported [14].

Since the STICLO studies have been completed, 30 years of clinical practice and extensive real-world use of STP have confirmed and refined its efficacy in DS, including its use in the long and very long term, with up to 24 years of exposure [12,13,14,15, 31,32,33,34] in adults and in infants [34,35,36]. Of particular clinical benefit is its effectiveness in reducing long-lasting seizures and episodes of SE, thereby reducing emergency hospitalizations and the need for rescue medication, and in improving the quality of life of patients and their families [13, 15, 33]. Also, prolonged STP therapy in DS tends to positively impact the longer-term prognosis of epilepsy, especially if initiated before adolescence [12, 14].

Conclusion

Overall, the pooled STICLO trials data demonstrate a rapid antiseizure efficacy of stiripentol in patients with Dravet syndrome, with highly significant responder rates, whatever the ≥ 50% or ≥ 75% reduction in seizure frequency level, and the number of patients becoming seizure-free are considered. Since stiripentol tolerability was acceptable in the trials, this marked efficacy together with the increase in seizure-free periods likely translates into improvements in patients' and caregivers’ quality of life.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available as they are the property of Biocodex, sponsor of the STICLO France and STICLO Italy studies.

References

Dravet C. Severe epilepsy in children. La Vie Médicale. 1978;8(2):543–8.

Dravet C. The core Dravet syndrome phenotype. Epilepsia. 2011;52(Suppl 2):3–9.

Li W, Schneider AL, Scheffer IE. Defining Dravet syndrome: an essential pre-requisite for precision medicine trials. Epilepsia. 2021;62(9):2205–17.

Sullivan J, Deighton AM, Vila MC, Szabo SM, Maru B, Gofshteyn JS, et al. The clinical, economic, and humanistic burden of Dravet syndrome—a systematic literature review. Epilepsy Behav. 2022;130: 108661.

Wirrell EC, Hood V, Knupp KG, Meskis MA, Nabbout R, Scheffer IE, et al. International consensus on diagnosis and management of Dravet syndrome. Epilepsia. 2022;63(7):1761–77.

Strzelczyk A, Lagae L, Wilmshurst J, Brunklaus A, Striano P, Rosenow F, et al. Dravet syndrome: a systematic literature review of the illness burden. Epilepsia Open. 2023;8:1256–70.

Domaradzki J, Walkowiak D. Caring for children with Dravet syndrome: exploring the daily challenges of family caregivers. Children. 2023;10(8):1410.

Perez J, Chiron C, Musial C, Rey E, Blehaut H, d’Athis P, et al. Stiripentol: efficacy and tolerability in children with epilepsy. Epilepsia. 1999;40(11):1618–26.

Guerrini R, Dravet C, Genton P, Belmonte A, Kaminska A, Dulac O. Lamotrigine and seizure aggravation in severe myoclonic epilepsy. Epilepsia. 1998;39(5):508–12.

Guerrini R, Tonnelier S, d’Athis P, Rey P, Vincent J, Pons G, et al. Stiripentol in severe myoclonic epilepsy in infancy (SMEI): a placebo-controlled italian trial. Epilepsia. 2002;43(Suppl. 8):155.

Chiron C, Marchand MC, Tran A, Rey E, d’Athis P, Vincent J, et al. Stiripentol in severe myoclonic epilepsy in infancy: a randomised placebo-controlled syndrome-dedicated trial. STICLO Study Group. Lancet. 2000;356(9242):1638–42.

de Liso P, Chemaly N, Laschet J, Barnerias C, Hully M, Leunen D, et al. Patients with Dravet syndrome in the era of stiripentol: a French cohort cross-sectional study. Epilepsy Res. 2016;125:42–6.

Myers KA, Lightfoot P, Patil SG, Cross JH, Scheffer IE. Stiripentol efficacy and safety in Dravet syndrome: a 12-year observational study. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2018;60(6):574–8.

Chiron C, Helias M, Kaminska A, Laroche C, de Toffol B, Dulac O, et al. Do children with Dravet syndrome continue to benefit from stiripentol for long through adulthood? Epilepsia. 2018;59(9):1705–17.

Chiron C, Chemaly N, Chancharme L, Nabbout R. Initiating stiripentol before 2 years of age in patients with Dravet syndrome is safe and beneficial against status epilepticus. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2023;65(12):1607–16.

Biocodex. Periodic benefit-risk evaluation report for the active substance stiripentol. 2022.

Dravet C, Bureau M, Guerrini R, Giraud N, Roger J. Severe myoclonic epilepsy in infants. In: Epileptic syndromes in infancy, childhood and adolescence, 2nd ed. Barnet: John Libbey and Company Ltd; 1992.

Brown LD, Cai T, DasGupta A. Interval estimation for a binomial proportion. Stat Sci. 2001;16(2):101–17.

Mohanraj RBM. Measuring the efficacy of antiepileptic drugs. Seizure. 2003;12(7):413–43.

Editorial. How best to serve children. Lancet 2000; 356:1619.

Kassaï B, Chiron C, Augier S, Cucherat M, Rey E, Gueyffier F, et al. Severe myoclonic epilepsy in infancy: a systematic review and a meta-analysis of individual patient data. Epilepsia. 2008;49(2):343–8.

Brigo F, Storti M. Antiepileptic drugs for the treatment of severe myoclonic epilepsy in infancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;11:CD010483.

Lattanzi S, Trinka E, Russo E, Del Giovane C, Matricardi S, Meletti S, et al. Pharmacotherapy for Dravet syndrome: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Drugs. 2023;15:1409–24.

Devinsky O, Cross JH, Laux L, Marsh E, Miller I, Nabbout R, et al. Trial of cannabidiol for drug-resistant seizures in the Dravet syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(21):2011–20.

Lagae L, Sullivan J, Knupp K, Laux L, Polster T, Nikanorova M, et al. Fenfluramine hydrochloride for the treatment of seizures in Dravet syndrome: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2019;394:2243–54.

Bishop KI, Isquith PK, Gioia GA, Gammaitoni AR, Farfel G, Galer BS, et al. Improved everyday executive functioning following profound reduction in seizure frequency with fenfluramine: analysis from a phase 3 long-term extension study in children/young adults with Dravet syndrome. Epilepsy Behav. 2021;121(Pt A): 108024.

Shmuely S, Sisodiya SM, Gunning WB, Sander JW, Thijs RD. Mortality in Dravet syndrome: a review. Epilepsy Behav. 2016;64:69–74.

Auvin S, Damera V, Martin M, Holland R, Simontacchi K, Saich A. The impact of seizure frequency on quality of life in patients with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome or Dravet syndrome. Epilepsy Behav. 2021;123: 108239.

Lo SH, Lloyd A, Marshall J, Vyas K. Patient and caregiver health state utilities in Lennox-Gastaut syndrome and Dravet syndrome. Clin Ther. 2021;43(11):1861–76.

Pinsent A, Weston G, Adams EJ, Linley W, Hawkins N, Schwenkglenks M, et al. Determining the relationship between seizure-free days and other predictors of quality of life in patients with Dravet syndrome and their carers from FFA registration studies. Neurol Ther. 2023;12(5):1593–606.

Inoue Y, Ohtsuka Y, Oguni H, Tohyama J, Baba H, Fukushima K, et al. Stiripentol open study in Japanese patients with Dravet syndrome. Epilepsia. 2009;50(11):2362–8.

Inoue Y, Ohtsuka Y. Long-term safety and efficacy of stiripentol for the treatment of Dravet syndrome: a multicenter, open-label study in Japan. Epilepsy Res. 2015;113:90–7.

Wirrell EC, Laux L, Franz DN, Sullivan J, Saneto RP, Morse RP, et al. Stiripentol in Dravet syndrome: results of a retrospective U.S. study. Epilepsia. 2013;54(9):1595–604.

Balestrini S, Doccini V, Boncristiano A, Lenge M, De Masi S, Guerrini R. Efficacy and safety of long-term treatment with stiripentol in children and adults with drug-resistant epilepsies: a retrospective cohort study of 196 patients. Drugs Real World Outcomes. 2022;9(3):451–61.

Thanh TN, Chiron C, Dellatolas G, Rey E, Pons G, Vincent J, et al. Long-term efficacy and tolerance of stiripentol in severe myoclonic epilepsy of infancy (Dravet’s syndrome. Arch Pediatr. 2002;9(11):1120–7.

Yamada M, Suzuki K, Matsui D, Inoue Y, Ohtsuka Y. Long-term safety and effectiveness of stiripentol in patients with Dravet syndrome: interim report of a post-marketing surveillance study in Japan. Epilepsy Res. 2020;170: 106535.

Acknowledgements

Authors thank Jérémie Lespinasse (eXYSTAT, Malakoff, France) for the realization of the statistics and figures.

Medical Writing and Editorial Assistance

The authors didn’t receive any medical writing or editorial assistance for this article.

Funding

This work was supported by Biocodex, the manufacturer of DIACOMIT® (stiripentol), which is also funding the journal’s Rapid Service Fee.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Renzo Guerrini, Laurent Chancharme, Benjamin Serraz and Catherine Chiron contributed equally to the concept and design, writing, review and editing of the present article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Renzo Guerrini has acted as a principal investigator for the STICLO Italy study, sponsored by Biocodex. He acted as an investigator for studies with Zogenix, Biocodex, UCB, Angelini and Eisai Inc. He has been a speaker and on advisory boards for Zogenix, Biocodex, Novartis, Biomarin and GW Pharma, outside the submitted work. Laurent Chancharme and Benjamin Serraz are full time employees of Biocodex. Catherine Chiron has acted as a principal investigator for the STICLO France study, sponsored by Biocodex. She has been a speaker and on advisory boards for Advicenne, BIAL, Biocodex, Eisai, GW Pharma, and Orphelia outside the submitted work.

Ethical Approval

According to the regulations, in France the protocol and informed consent form were submitted for review and approved by the Ethics Committee of the principal investigator, Paris-Cochin Hospital Center. In Italy the protocol and informed consent form were reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committees of each center (listed in the Supplementary Material). Both studies were performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964, and its later amendments, Good Clinical Practices, and according to the local regulatory requirements in force in France and in Italy. Parents and children were informed about the aim of the study, its duration, the method used, the benefits that the children could get from this study as well as the potential constraints and risks. Written informed consent of the parents or the authorized representative of participant in this study was required before study enrolment. The informed consent was to be signed, witnessed (if signed by a representative), dated and stored by the investigator.

Additional information

Prior Presentation: results displayed in this article have been partially presented as a poster at the American Epilepsy Society Annual Meeting in Orlando, December 1–5, 2023.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Guerrini, R., Chancharme, L., Serraz, B. et al. Additional Results from Two Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trials of Stiripentol in Dravet Syndrome Highlight a Rapid Antiseizure Efficacy with Longer Seizure-Free Periods. Neurol Ther 13, 869–884 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40120-024-00623-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40120-024-00623-8