Abstract

Introduction

Experts agree that there is a need for protocols to guide health professionals on how to best manage psychiatric comorbidities in patients with epilepsy (PWE). We aimed to develop practical recommendations for key issues in the management of depression in PWE.

Methods

This was a qualitative study conducted in four steps: (1) development of a questionnaire on the management of depression in PWE to be answered; (2) literature review and, if evidence from guidelines/consensus or systematic reviews was available, drafting initial recommendations; (3) a nominal group methodology for reviewing initial recommendations and formulating new recommendations on those issues without available evidence; and (4) drafting and approving the final recommendations. A scientific committee (one neurologist and one psychiatrist) was responsible for the development of the project and its scientific integrity. The scientific committee selected a panel of experts (nine neurologists and nine psychiatrists with experience in this field) to be involved in the nominal group meetings and to formulate final recommendations.

Results

Fifteen recommendations were formulated. Four on the screening and diagnosis: screening and diagnosis of depression, evaluation of the risk of suicide, and diagnosis of depression secondary to epilepsy; nine on the management of depression: referral to a psychiatrist, selection of the antiseizure medication, change of antiseizure medication, antidepressant treatment initiation, selection of antidepressant, use of antidepressants during pregnancy, use of psychotherapy, antidepressant treatment duration, and discontinuation of antidepressant treatment; two on the follow-up: duration of the follow-up under usual conditions, and follow-up of patients at risk of suicide.

Conclusion

We provide recommendations based on expert opinion consensus to help healthcare professionals assess depression in PWE. The detection and treatment of major depressive disorders are key factors in improving epilepsy outcomes and avoiding suicide risk.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this study? |

Experts agree that there is a need for protocols to guide healthcare professionals on how to best manage psychiatric comorbidities in PWE. |

The aim of this project was to develop practical recommendations for key issues in the management of depression in PWE, including screening, diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up. |

What was learned from the study? |

The experts agreed four recommendations on the screening and diagnosis, nine on the management of depression, and two on the follow-up. |

The detection and treatment of major depressive disorders are key factors in improving epilepsy outcomes and avoiding suicide risk. |

Introduction

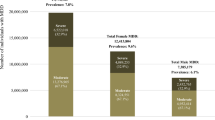

Psychiatric comorbidities are frequent in patients with epilepsy (PWE). Thus, according to a recent meta-analysis, the prevalence of any psychiatric disorder in PWE is 43.3%, and the most common comorbidities are mood disorders and anxiety disorders [1]. Among the mood disorders, major depressive disorder is the most frequent comorbidity; when using a gold standard diagnostic tool, the prevalence of major depressive disorder in PWE was 21.9% [2], over the upper limit of the range reported for the general population [3]. The relationship between depression and epilepsy seems to be bidirectional [4, 5].

The presence of depression in PWE is associated with worse outcomes, including a greater impairment of the quality of life, increased seizure severity, greater risk of pharmacoresistance, increased side effects of antiseizure medications (ASMs), increased risk of accidents and injuries, and ultimately, increased mortality [4]. PWEs are at greater risk of suicide, showing a prevalence of suicide ideation of 23.2%, a prevalence of suicide attempts of 7.4%, and a rate of death due to suicide of 0.5% [6]. Although depression plays a role in the risk of suicide of PWE, the relationships among epilepsy, depression, and suicide are complex, with depression mediating the association between seizure frequency or stigma and an increased risk of suicide but with the involvement of other factors, such as unemployment and anxiety [7, 8]. ASMs and epilepsy surgery have been reported to be associated with suicidal ideation and behavior [9], although this issue is controversial [10].

Despite the impact of depression on PWE, it often remains unrecognized and undertreated. A recent survey from the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) conducted among 338 epilepsy health professionals from 67 countries showed that 28% of the respondents screened for depression in PWE only if the patients spontaneously reported symptoms of depression, and once depression was identified, 27% of the respondents adopted a watchful waiting attitude [11]. The situation for the screening of suicidality is even more worrisome since, in that survey, 58% of the health professionals reported that they screen for suicidal ideation only if symptoms are spontaneously reported [11]. These figures, based on the opinion of healthcare professionals, are likely to be optimistic, and higher figures of underdiagnosis and undertreatment of depression among PWE have been reported when using clinical samples [12].

The authors of the abovementioned ILAE survey concluded that there is a need for protocols to guide health professionals on how to best manage psychiatric comorbidities in PWE [11]. Very few attempts to produce recommendations for the management of depression in PWE have been made [13, 14], and the latest and more updated clinical practice recommendations from the ILAE have been focused on the pharmacological treatment of depression [15]. The aim of this project was to develop practical recommendations for key issues in the management of depression in PWE, including screening, diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up using a qualitative methodology.

Methods

Compliance with ethics guidelines

This work is based on previously conducted studies and the clinical expertise of the authors in treating patients with epilepsy and/or depression. No new clinical studies were performed by the authors. No patient-specific efficacy or safety data were reported; therefore, institutional review board (IRB)/ethics approval was not required for the consensus recommendations. All panelists were aware of the objectives of the study and verbally agreed to participate in the development and publication of the recommendations.

Design

This was a qualitative study conducted in four steps: (1) development of a questionnaire on the management of depression in PWE to be answered; (2) literature review and, if evidence from guidelines/consensus or systematic reviews was available, drafting initial recommendations; (3) a nominal group methodology for reviewing initial recommendations and formulating new recommendations on those issues without available evidence; and (4) drafting and approving the final recommendations (Fig. 1). Since the study did not involve the participation of any person distinct from the specialists involved in the elaboration of the recommendations, ethical approval or informed consent was not needed.

Development of the Project

A scientific committee of two specialists, one neurologist (VV) and one psychiatrist (JB), members of scientific societies of their specialties, were responsible for the development of the project and its scientific integrity. The scientific committee selected a group of nine neurologists and nine psychiatrists with experience in this field who formed the expert panel group (all byline authors) involved in the nominal groups and to formulate final recommendations.

The scientific committee agreed on the questionnaire about the management of depression in PWE to be answered. A literature search from inception to January 2022 was performed by a medical information specialist (ISA, see acknowledgments) and a methodologist (FRV, see acknowledgments) using the Web of Science. The literature search was performed with the following search string: TI = ((Epilepsy OR epileptic OR seizure*) AND (depression OR depressive OR psychiatr* OR mood OR affective OR anxiety OR bipolar OR panic OR Posttraumatic OR Post-traumatic OR phobia) AND (TI = (guideline* OR consensus OR meta-analysis OR meta-analysis OR “systematic review” OR statement) OR AB = (guideline* OR consensus OR meta-analysis OR meta-analysis OR “systematic review” OR statement)). The methodologist revised the output of the literature search, selected references that could provide any information to answer the questions posed by the scientific committee, providing that the references were guidelines/consensus or meta-analyses/systematic reviews and were published in English or Spanish, and then extracted the verbatim information that could answer those questions into an MS Excel form. In a second meeting, the scientific committee reviewed the extracted information and, based on it, whenever possible, drafted an answer to the questions (i.e., an initial recommendation).

The nominal group is a qualitative method for providing recommendations on a specific topic when the evidence is very limited or contradictory. It uses a structured meeting to gather information from relevant experts about a given issue [16] and usually includes a silent generation, round-robin discussion, clarification and ranking of ideas [17]. An explanation of the methodology and its applications can be found elsewhere [16, 17]. In our project, the process of the nominal group was coordinated by an expert from a contract research organization (HP, see acknowledgments).

The silent generation of ideas was produced individually prior to the nominal group meetings. To do so, the experts received information on the literature search, the information extracted from the pertinent documents, and the initial recommendations agreed upon by the scientific committee. The experts could provide comments on the initial recommendations and their ideas on any questions without an initial recommendation. The information provided by the experts during the prework was compiled by the coordinator of the nominal groups and summarized into affirmative statements.

During two nominal group meetings, the information from the silent prework was presented to the experts, who discussed the statements and voting during the meeting using the Slido platform. The cutoff for consensus was set at two-thirds (i.e., 66.6%) of the responses. Recommendations were redrafted using information from the voting and were presented and discussed with the scientific committee in a third meeting. The final recommendations were reviewed and approved by all participants. In addition, these recommendations have been endorsed by the Spanish Society of Psychiatry and Mental Health (Sociedad Española de Psiquiatría y Salud Mental) and the Spanish Society of Neurology (Sociedad Española de Neurología).

Results

Questionnaire Drafting

The questionnaire developed by the scientific committee comprised 16 questions: five on the screening, diagnosis, and referral, nine on the treatment of PWE with depression, and two on the follow-up of PWE with depression; five items were split into two questions each, totaling 21 questions (Table S1 in the supplementary material).

The Literature Search and the Initial Recommendations

The literature search identified 128 records. After the records were reviewed, nine articles were considered to provide useful information for answering some of the questions posed by the scientific committee [13,14,15, 18,19,20,21,22,23], including a series of guidelines/consensus documents.

With the information extracted from those documents, the scientific committee considered that an initial recommendation could be stated for seven of the 21 questions. The questions, the information from the literature supporting the recommendation, and the initial recommendations for those seven questions are presented in Table S1.

Nominal Group

During the nominal group meeting, among the seven statements agreed upon by the scientific committee as recommendations, one remained unchanged: “How long should antidepressant treatment be maintained in PWE?” The question on “How long should psychotherapy be maintained in PWE and depression?” was discarded by the expert panel since it was considered that the important issue is the number of recommended sessions, which was addressed by another question. These two questions were not included in the voting. The remaining five questions were modified by the expert panel and included in the voting.

Thus, 19 of the 21 questions initially set were discussed and voted on during the nominal group: 14 without an initial recommendation from the scientific committee and five with an initial recommendation from the scientific committee based on the available evidence. After the discussion and voting, new recommendations were agreed upon for those 14 questions without an initial recommendation. From the five questions with an initial recommendation from the scientific committee, three questions were modified, and there was no consensus for modifying two of the initial statements of the scientific committee, that is, the one related to the question “What screening tool for depression should be used for PWE?” and one for “How should antidepressant treatment be discontinued in PWE?” (Table 1). The specific results of the voting during the nominal groups for the 19 questions that underwent evaluation and the statements agreed upon are summarized in Table 1.

During the final review of the recommendations, one of the questions agreed upon in the nominal groups, the one regarding antidepressants and pregnancy, was further discussed since some panelists disagreed with the recommendation. The final recommendation included below was the one agreed upon after this latter discussion.

Recommendations

The agreed upon recommendations are shown in Box 1.

Box 1. Recommendations for the Management of Depression in PWE

Screening and diagnosis |

For depression screening in PWE, the Neurological Disorders Depression Inventory for Epilepsy (NDDI-E) with a cutoff point of > 13 is recommended |

In PWE, it is recommended that a neurologist and/or psychiatrist make a diagnosis of depression through anamnesis and following the ICD-10 diagnostic criteria |

In PWE, it is recommended that the neurologist and/or psychiatrist evaluate the risk of suicide through anamnesis |

Depression is considered to be secondary to epilepsy in those patients in whom depressive symptoms occur with seizures (peri-ictal) or when they are related to ASM |

Management of depression |

In PWE, it is recommended to refer the patient to a psychiatrist as soon as possible if there is suspicion of another psychiatric comorbidity, psychotic depression, bipolar disorder, risk of suicide, or if there is no response to the second antidepressant treatment (at adequate dose, duration, and adherence) or if augmentation of antidepressant treatment is needed |

In PWE and depression, the selection of ASM will depend on the characteristics of the disease and the patient's profile. In general, the use of lamotrigine, valproate, eslicarbazepine acetate, carbamazepine, and oxcarbazepine is recommended; the use of levetiracetam, phenobarbital, topiramate, and perampanel is less recommendeda |

It is suggested to change ASM in a PWE diagnosed with depression if a causal relationship between the ASM and the depressive episode is suspected or if the depressive symptoms may worsen due to the ASM treatment |

In PWE and depression, it is recommended to start treatment for depression as soon as possible after diagnosis, especially if there is a risk of suicide |

In PWE and depression, antidepressant treatment selection will depend on the characteristics of the disease and the patient’s profile. In general, the use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and dual-type antidepressants is recommended; bupropion, clomipramine, and maprotiline are less recommendeda |

In pregnant PWE and depression, a risk–benefit balance should be made between using antidepressants and not using them. The patient should be informed of that risk–benefit evaluation to allow shared decision-making between the clinician and the patient; this process should be recorded in the clinical chart. If an antidepressant is needed, SSRIs and SNRIs are usually the first-choice treatment for this population |

In PWE and mild depressive episodes, psychotherapy is recommended, and if the depressive episodes are moderate–severe, psychotherapy in combination with antidepressant treatment is recommended. In each case, the psychotherapist will establish the number of psychotherapy sessions depending on the patient and the type of therapy established |

It is recommended to continue antidepressant treatment for a minimum of 6 months after remission in patients with a first episode and a minimum of 9 months in cases of a recurrent episode or severe depression |

When an antidepressant should be discontinued, it is recommended to do so gradually over 1–4 weeks |

Follow-up |

Follow-up of PWE and depression must be maintained according to the specialist’s judgment, generally recommending follow-up for at least 6–12 months after remission of depressive symptoms and withdrawal of treatment |

The psychiatric follow-up of a PWE at risk of suicide must be maintained according to the psychiatrist’s judgment, following the recommendations and/or follow-up clinical protocols established at their center |

Discussion

Depression is frequent in PWE and is associated with worse outcomes [24]. However, despite its importance, it is frequently unrecognized and undertreated. We have agreed on a set of recommendations on the screening, diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up of depression in PWE that are intended to guide health professionals in its management. Next, we discuss these recommendations in the context of the available evidence and/or existing guidelines.

Screening and Diagnosis

For depression screening in PWE, the Neurological Disorders Depression Inventory for Epilepsy (NDDI-E) with a cutoff point of > 13 is recommended.

In PWE, depression is frequently underdiagnosed [11, 12]. Therefore, it is important to stress the need for the screening of depression in PWE. A systematic review of the literature reported 16 screening tools for depression in PWE [20]; however, the most frequently used and developed tool specifically for PWE is the six-item Neurological Disorders Depression Inventory for Epilepsy (NDDI-E) [25]. In contrast to other generic screening tools, the association between depression and the NDDI-E does not appear to be affected by the adverse effects of ASMs [25]. This tool was recommended by a consensus of the Mood Disorder Initiative-Epilepsy Foundation [13], which, consistent with the results of the validation [25], indicated a score of 15 or above as suggestive of a major depressive episode [13]. However, in a recent meta-analysis using data from 13 validation studies, Kim et al. [21] reported that the optimal cutoff for detecting major depression is > 13.

In PWE, it is recommended that a neurologist and/or psychiatrist make a diagnosis of depression through anamnesis and following the ICD-10 diagnostic criteria.

Some guidelines mixed the use of a structured interview with screening tools such as NDDI-E or the Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale for use as “diagnostic tests” [18]. However, it is important to stress that these latter instruments are not diagnostic [13]. The diagnosis should be made at the point of care by the neurologist and/or psychiatrist on the basis of the symptoms elicited during the anamnesis and following standardized diagnostic criteria such as those of the International Classification of Diseases 10th revision (ICD-10) [26], more commonly used in the European setting, or the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, Text Revision (DSM–5-TR) [27] used in the US setting.

In PWE, it is recommended that the neurologist and/or psychiatrist evaluate the risk of suicide through anamnesis.

Regardless of the presence of depression, the risk of suicide in PWE is high [6]. If the underdiagnosis of depression in PWE is an important issue, the situation regarding the evaluation of the risk of suicide is highly worrisome since the survey of the ILAE mentioned previously indicates that, in most cases, there is no active screening of the risk of suicide among PWE [11]. It is important to stress that most patients who commit suicide visit a healthcare provider within months before their death; therefore, according to some prior recommendations, screening for suicidality should be an integral part of the evaluation of every PWE during all follow-ups [9]. This screening should be made during the anamnesis. The healthcare professional involved in the management of PWE could base the screening on the five simple questions developed by the US National Institute of Mental Health that are contained in the Suicide Risk Screening Tool [28].

Depression is considered to be secondary to epilepsy in those patients in whom depressive symptoms occur with seizures (peri-ictal) or when they are related to ASM.

The occurrence of mood changes temporarily related to seizure occurrence is a well-known phenomenon [4], and it is not unusual that they persist into the post-ictal period [13]. For some authors, distinguishing between peri-ictal and interictal depressive symptoms may condition the treatment since for peri-ictal symptoms of depression to remit, total seizure remission is necessary [29]. The specialist should, however, bear in mind the coexistence of peri-ictal and interictal depressive symptoms [29].

ASMs with negative psychotropic properties (phenobarbital, primidone, levetiracetam, topiramate, zonisamide, and perampanel) can cause psychiatric adverse events, including depression [30], and are at greater risk for patients with a past or current personal or family psychiatric history [30, 31]. Using the Columbia and Yale Antiepileptic Drugs Database Project, Chen et al. [32] reported that levetiracetam (7%) and zonisamide (4%) were associated with a significantly higher frequency of depression than other ASMs, while lamotrigine (1%) showed a significantly lower frequency of depression. The use of monotherapy and slow titration schedules may reduce the risk or occurrence of depression associated with ASMs [33]. In patients with epilepsy and depression, some experts favor the use of lamotrigine, oxcarbazepine, valproic acid, and clonazepam, while they consider that levetiracetam, topiramate, and zonisamide should be used with caution [30].

Despite the relationship between ASMs and the presence of depression and other psychiatric comorbidities and the warning included by the US Food and Drug Administration in the prescribing information of all ASMs regarding the risk of suicide, the current evidence to support a potential association between ASMs and suicide is not robust enough, and the debate on this issue continues [10].

Management of Depression

In PWE, it is recommended to refer the patient to a psychiatrist as soon as possible if there is suspicion of another psychiatric comorbidity, psychotic depression, bipolar disorder, risk of suicide, or if there is no response to the second antidepressant treatment (at adequate dose, duration, and adherence) or if augmentation of antidepressant treatment is needed.

There is a general agreement among the several guidelines consulted that PWE with psychotic depression, bipolar disorder, risk of suicide, or those who require potentiation of antidepressant treatment should be referred to a psychiatrist for further management [13, 15, 18].

We also consider that patients with other psychiatric comorbidities or who have failed two trials of antidepressants are more difficult to treat and, therefore, should be referred to a psychiatrist. Patients with depression and psychiatric comorbidity usually exhibit a greater symptom burden, a worse course, and poor outcomes [34]. Although there is no universally accepted definition, failure to respond or achieve remission after two or more trials of antidepressants of adequate dose and duration is considered treatment-resistant depression [35].

In PWE and depression, the selection of ASM will depend on the characteristics of the disease and the patient's profile. In general, the use of lamotrigine, valproate, eslicarbazepine acetate, carbamazepine, and oxcarbazepine is recommended; the use of levetiracetam, phenobarbital, topiramate, and perampanel is less recommended.

The selection of an ASM will depend on clinical variables such as seizure type, age, sex, comorbidities, comedications, allergy history, and childbearing potential. A group of international experts has developed an algorithm to assist in the selection of ASM accounting for these factors [36], and its implementation seems to be associated with better treatment outcomes [37]. According to this algorithm, seizure type is the critical factor for the selection of ASM, and afterward, selection should be tailored considering 16 patients’ characteristics, including the presence of depression [36]. In this algorithm, lamotrigine is upgraded in PWE and depression, and as shown in Table 1, we fully agree with that recommendation. However, we think that there are some other ASMs that have shown some mood-stabilizing properties or have less impact on the occurrence of depression as a side effect (see above); these ASMs may be more desirable than others. Some authors recommend sodium channel blockers for PWE with a psychiatric comorbidity [38]. However, it is obvious that a recommendation for selecting the most appropriate ASM cannot be made on the basis of a single clinical characteristic. Selection of treatment is complex, and all of the factors included in that algorithm should be considered when selecting the ASM, and we should add the specialist’s experience and the patient’s preferences to the decision-making.

It is suggested to change ASM in a PWE diagnosed with depression if a causal relationship between the ASM and the depressive episode is suspected or if the depressive symptoms may worsen due to the ASM treatment.

Iatrogenic depression associated with ASMs is well recognized [4, 13, 39]; however, we were not able to find specific recommendations on how to manage it except for a mention in a consensus statement. Thus, Barry et al. [13] comment that PWE who exhibit depressive symptoms associated with an ASM “may respond to a medication change”. They also add that if the medication change is not advisable, “the introduction of an antidepressant can be considered” [13].

Although the lack of any evidence in this regard should be highlighted, this group of experts considers that, except when otherwise clinically contraindicated, in PWE with iatrogenic depression or those whose depressive symptoms could be aggravated by the ASM, a change in the ASM is recommended. The decision-making process must include weighing up the benefits (e.g., to avoid worsening of depressive symptoms) and risks (e.g., seizure recurrence) of switching therapy.

In PWE and depression, it is recommended to start treatment for depression as soon as possible after diagnosis, especially if there is a risk of suicide.

Consistent with clinical practice recommendations in this field [14], we recommend that the treatment of depression in PWE should be started as soon as possible. In cases of risk of suicide, the patient should be referred to a psychiatrist and urgently treated.

As mentioned above, the ILAE survey showed that a relevant proportion of specialists adopt a watchful waiting approach [11]. In our view, this approach is not justified. Although some studies have been performed to evaluate a watchful waiting approach in patients with mild to moderate depression [40, 41], overall, we think there is no compelling evidence to support a watchful waiting approach (i.e., no psychotherapy or pharmacotherapy), even in patients with mild depression. Mild depression can impair function and threaten life and quality of life [42]; therefore, in our view, unless robust evidence otherwise becomes available, it seems judicious to provide some kind of intervention.

In PWE and depression, antidepressant treatment selection will depend on the characteristics of the disease and the patient’s profile. In general, the use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and dual-type antidepressants is recommended; bupropion, clomipramine, and maprotiline are less recommended.

We agree with some experts who argue that the evidence on the treatment of depression in PWE is very limited, and the treatment should rely on individual clinical experience [4]. None of the available guidelines for PWE and depression recommend specific antidepressant drugs for PWE [15, 18]. Instead, they generically recommend selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) [15, 18] or serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) [18].

A recent updated systematic review from the Cochrane Collaboration found four randomized trials that evaluated two SSRIs (sertraline and paroxetine), one SNRI (venlafaxine), and a tricyclic antidepressant (amitriptyline); they also included in their review six nonrandomized studies [19]. They concluded that the evidence is very limited (only a low certainty of evidence that venlafaxine is superior to no treatment) and that it cannot inform the selection of antidepressants for PWE [19].

We agree with the Consensus of the Mood Disorder Initiative-Epilepsy Foundation that some antidepressants (namely, clomipramine, bupropion, and maprotiline) are best avoided in PWE [13]; the consensus includes amoxapine, which is not available in Europe for the treatment of depression. Some experts also agree that maprotiline, the immediate release formulation of bupropion, and high doses of clomipramine may be associated with seizure worsening [4].

However, this is only a general recommendation, and treatment selection should be tailored to patient characteristics. As is the case for the selection of ASM, the selection of an antidepressant should be based on several factors, such as clinical features, comorbid conditions, response and side effects during the previous use of antidepressants, patient preference, potential interactions, comparative efficacy and tolerability, simplicity of use, and cost and availability [43].

In pregnant PWE and depression, a risk–benefit balance should be made between using antidepressants and not using them. The patient should be informed of that risk–benefit evaluation to allow shared decision-making between the clinician and the patient; this process should be recorded in the clinical chart. If an antidepressant is needed, SSRIs and SNRIs are usually the first-choice treatment for this population.

Clinical practice guidelines on the use of antidepressants during pregnancy state that decisions on whether to continue or start antidepressant treatment need to be individualized and that none of the currently available antidepressants is absolutely contraindicated in pregnancy [44]. They added that SSRIs account for the largest evidence base around reproductive safety and, thus, this makes them first-choice treatments preconception and during the pregnancy for antidepressant-naïve women [44].

Some authors recommend to first weigh the risk and benefits of treatment with antidepressants compared to untreated illness; if the assessment favors treatment with antidepressants, the antidepressant should be initiated on the basis of an individualized risk/benefit assessment and discussion, with the patient’s history of response to previous antidepressants and preferences guiding the treatment decisions [45]. To avoid exposure to both illness and medication, they recommend the use of the lowest possible dose while also avoiding undertreatment [45]. Regarding the selection of the antidepressant, they consider that unless there is a reason to use another class of antidepressants, SSRIs are considered first-line treatments [45].

In PWE and mild depressive episodes, psychotherapy is recommended, and if the depressive episodes are moderate–severe, psychotherapy in combination with antidepressant treatment is recommended. In each case, the psychotherapist will establish the number of psychotherapy sessions depending on the patient and the type of therapy established.

This recommendation is consistent with the one from the ILAE [15] and with those from general clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of depression [42]. Some factors may suggest the use of psychotherapy, including the presence of significant psychosocial stressors, intrapsychic conflict, interpersonal difficulties, treatment availability, pregnancy, and patient preference [42]. The level of evidence supporting each type of psychotherapy can be found elsewhere [46, 47], but it seems that cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and interpersonal psychotherapy have higher levels of evidence [42, 46, 47].

Gandy et al. [22], in a systematic review of the literature, reported that all randomized controlled trials showing positive effects on depression were those aiming to improve depression, while those trials in which CBT was focused on improving seizure control did not show improvement of depression. Using a systematic review of randomized studies, Noble et al. [23] reported that CBT in PWE is associated with a statistically significant improvement of depression, but in over two-thirds of the patients, the effect on depression is not meaningful.

It is recommended to continue antidepressant treatment for a minimum of 6 months after remission in patients with a first episode and a minimum of 9 months in cases of a recurrent episode or severe depression.

This recommendation is consistent with previous recommendations from the ILAE [15] and the Consensus of the Mood Disorder Initiative-Epilepsy Foundation [13] and with those of the general clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of depression [42, 43]. Some patients with risk factors for recurrence will require a longer duration of antidepressant treatment [42, 43], but most of those patients, at some time during the follow-up, should be referred to a psychiatrist; the presence of a comorbid chronic medical condition is one of those risk factors [42, 43].

When an antidepressant should be discontinued, it is recommended to do so gradually over 1–4 weeks.

Up to 40% of patients who abruptly discontinue antidepressants experience a discontinuation syndrome characterized by flu-like symptoms, insomnia, nausea, sensory disturbances, and hyperarousal [43]. The risk of occurrence is higher for antidepressants with a short half-life, more specifically with paroxetine and SNRIs (i.e., venlafaxine, desvenlafaxine, and duloxetine) [48]. Once this syndrome occurs, there is no robust evidence to guide its management [49]. The most important measure is the prevention of its occurrence and the main recommendation is to gradually taper the antidepressant. The duration of the taper will depend on the type of antidepressant, dose, and treatment duration [50].

Follow-up

Follow-up of PWE and depression must be maintained according to the specialist's judgment, generally recommending follow-up for at least 6-12 months after remission of depressive symptoms and withdrawal of treatment.

The lifetime risk of recurrence after a first major depressive episode is high, and importantly, between one-third and half of the patients will experience recurrence within 1 year after treatment discontinuation [51]. Therefore, follow-up of these patients is imperative.

The psychiatric follow-up of a PWE at risk of suicide must be maintained according to the psychiatrist’s judgment, following the recommendations and/or follow-up clinical protocols established at their center.

Suicide risk management is beyond the scope of this document. We can only stress the importance of following the established protocols for managing suicide risk in the psychiatrist setting. From the neurologists’ perspective, their role is key and was mentioned above: screening for the suicide risk among PWE.

Limitations and Strengths

The main limitation of this study is that the list of questions was not exhaustive, although it comprised what was considered key in the management of these patients. Moreover, the method for reaching the recommendations is based on consensus; therefore, they should be considered with the low certainty associated with their level of evidence. The main strength is that the study followed a recognized qualitative methodology for reaching consensus on a relevant topic with uncertainties in patients with epilepsy. Our recommendations are focused on the management of depression in PWE. We do not pay attention to other important issues on the management of epilepsy, such as the occurrence of sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP; i.e., death in a patient with epilepsy that is not due to trauma, drowning, status epilepticus, or other known causes). For instance, the potential risk of SUDEP in PWE who switch from an ASM due to its undesirable effects on depression has not been considered. Similarly, we have not included information on the potential drug–drug interactions between ASMs and antidepressants.

Conclusions

Despite the high prevalence of major depressive episodes in PWE, the evidence management guidelines are limited. Data from recent surveys suggest that there can be relevant improvements in the detection and treatment of depression, as well as a need to perform an active screening for suicide.

We provide recommendations based on expert opinion consensus to help health professionals manage depression in PWE. The detection and treatment of major depressive disorders are key factors for improving epilepsy outcomes and avoiding suicide risk.

References

Gurgu RS, Ciobanu AM, Danasel RI, Panea CA. Psychiatric comorbidities in adult patients with epilepsy (a systematic review). Exp Ther Med. 2021;22:909.

Kim M, Kim YS, Kim DH, Yang TW, Kwon OY. Major depressive disorder in epilepsy clinics: a meta-analysis. Epilepsy Behav. 2018;84:56–69.

Gutierrez-Rojas L, Porras-Segovia A, Dunne H, Andrade-Gonzalez N, Cervilla JA. Prevalence and correlates of major depressive disorder: a systematic review. Braz J Psychiatry. 2020;42:657–72.

Mula M. Developments in depression in epilepsy: screening, diagnosis, and treatment. Expert Rev Neurother. 2019;19:269–76.

Kanner AM, Ribot R, Mazarati A. Bidirectional relations among common psychiatric and neurologic comorbidities and epilepsy: do they have an impact on the course of the seizure disorder? Epilepsia Open. 2018;3:210–9.

Abraham N, Buvanaswari P, Rathakrishnan R, et al. A meta-analysis of the rates of suicide ideation, attempts and deaths in people with epilepsy. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:1451.

Liu X, Chen H, Zheng X. Effects of seizure frequency, depression and generalized anxiety on suicidal tendency in people with epilepsy. Epilepsy Res. 2020;160: 106265.

Zhao Y, Liu X, **ao Z. Effects of perceived stigma, unemployment and depression on suicidal risk in people with epilepsy. Seizure. 2021;91:34–9.

Kanner AM. Suicidality in patients with epilepsy: why should neurologists care? Front Integr Neurosci. 2022;16:898547.

Mula M. Suicidality and antiepileptic drugs in people with epilepsy: an update. Expert Rev Neurother. 2022;22:405–10.

Gandy M, Modi AC, Wagner JL, et al. Managing depression and anxiety in people with epilepsy: a survey of epilepsy health professionals by the ILAE Psychology Task Force. Epilepsia Open. 2021;6:127–39.

Scott AJ, Sharpe L, Thayer Z, et al. How frequently is anxiety and depression identified and treated in hospital and community samples of adults with epilepsy? Epilepsy Behav. 2021;115: 107703.

Barry JJ, Ettinger AB, Friel P, et al. Consensus statement: the evaluation and treatment of people with epilepsy and affective disorders. Epilepsy Behav. 2008;13(Suppl 1):S1–29.

Kerr MP, Mensah S, Besag F, et al. International consensus clinical practice statements for the treatment of neuropsychiatric conditions associated with epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2011;52:2133–8.

Mula M, Brodie MJ, de Toffol B, et al. ILAE clinical practice recommendations for the medical treatment of depression in adults with epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2022;63:316–34.

Jones J, Hunter D. Consensus methods for medical and health services research. BMJ. 1995;311:376–80.

McMillan SS, King M, Tully MP. How to use the nominal group and Delphi techniques. Int J Clin Pharm. 2016;38:655–62.

Martinez-Juarez IE, Flores-Sobrecueva A, Alanis-Guevara MI, et al. Clinical guidelines: epilepsy and psychiatric comorbidities. Rev Mex Neurocienc. 2020;21:39–55.

Maguire MJ, Marson AG, Nevitt SJ. Antidepressants for people with epilepsy and depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;4:CD010682.

Gill SJ, Lukmanji S, Fiest KM, Patten SB, Wiebe S, Jette N. Depression screening tools in persons with epilepsy: a systematic review of validated tools. Epilepsia. 2017;58:695–705.

Kim DH, Kim YS, Yang TW, Kwon OY. Optimal cutoff score of the neurological disorders depression inventory for epilepsy (NDDI-E) for detecting major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis. Epilepsy Behav. 2019;92:61–70.

Gandy M, Sharpe L, Perry KN. Cognitive behavior therapy for depression in people with epilepsy: a systematic review. Epilepsia. 2013;54:1725–34.

Noble A, Reilly J, Temple J, Fisher P, Snape D. Cognitive-behavioural therapy does not meaningfully reduce depression in most people with epilepsy: a systematic review with a reliable change analysis. Epilepsia. 2018;59:S242–3.

Mula M, Kanner AM, Jette N, Sander JW. Psychiatric comorbidities in people with epilepsy. Neurol Clin Pract. 2021;11:e112–20.

Gilliam FG, Barry JJ, Hermann BP, Meador KJ, Vahle V, Kanner AM. Rapid detection of major depression in epilepsy: a multicentre study. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5:399–405.

World Health Organization. The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1992.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5-TR (Fifth Edition, Text Revision). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2022.

Horowitz LM, Snyder DJ, Boudreaux ED, et al. Validation of the ask suicide-screening questions for adult medical inpatients: a brief tool for all ages. Psychosomatics. 2020;61:713–22.

Kanner AM. The treatment of depressive disorders in epilepsy: what all neurologists should know. Epilepsia. 2013;54(Suppl 1):3–12.

Kanner AM, Bicchi MM. Antiseizure medications for adults with epilepsy: a review. JAMA. 2022;327:1269–81.

Kanner AM, Patten A, Ettinger AB, Helmstaedter C, Meador KJ, Malhotra M. Does a psychiatric history play a role in the development of psychiatric adverse events to perampanel… and to placebo? Epilepsy Behav. 2021;125:108380.

Chen B, Choi H, Hirsch LJ, et al. Psychiatric and behavioral side effects of antiepileptic drugs in adults with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2017;76:24–31.

Mula M, Sander JW. Negative effects of antiepileptic drugs on mood in patients with epilepsy. Drug Saf. 2007;30:555–67.

Kim J, Schwartz TL. Psychiatric comorbidity in major depressive disorder. In: McIntyre RS, editor. Major depressive disorder. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2020. p. 91–102.

McIntyre RS, Filteau MJ, Martin L, et al. Treatment-resistant depression: definitions, review of the evidence, and algorithmic approach. J Affect Disord. 2014;156:1–7.

Asadi-Pooya AA, Beniczky S, Rubboli G, Sperling MR, Rampp S, Perucca E. A pragmatic algorithm to select appropriate antiseizure medications in patients with epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2020;61:1668–77.

Hadady L, Klivenyi P, Perucca E, et al. Web-based decision support system for patient-tailored selection of antiseizure medication in adolescents and adults: an external validation study. Eur J Neurol. 2022;29:382–9.

Villanueva V, Sanchez-Alvarez JC, Carreno M, Salas-Puig J, Caballero-Martinez F, Gil-Nagel A. Initiating antiepilepsy treatment: an update of expert consensus in Spain. Epilepsy Behav. 2021;114: 107540.

Kanner AM. Management of psychiatric and neurological comorbidities in epilepsy. Nat Rev Neurol. 2016;12:106–16.

Iglesias-Gonzalez M, Aznar-Lou I, Gil-Girbau M, et al. Comparing watchful waiting with antidepressants for the management of subclinical depression symptoms to mild-moderate depression in primary care: a systematic review. Fam Pract. 2017;34:639–48.

Iglesias-Gonzalez M, Aznar-Lou I, Penarrubia-Maria MT, et al. Effectiveness of watchful waiting versus antidepressants for patients diagnosed of mild to moderate depression in primary care: a 12-month pragmatic clinical trial (INFAP study). Eur Psychiatry. 2018;53:66–73.

American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder. 3rd ed. Arlington: American Psychiatric Association; 2010.

Kennedy SH, Lam RW, McIntyre RS, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) 2016 clinical guidelines for the management of adults with major depressive disorder: section “RESULTS”. Pharmacological treatments. Can J Psychiatry. 2016;61:540–60.

McAllister-Williams RH, Baldwin DS, Cantwell R, et al. British Association for Psychopharmacology consensus guidance on the use of psychotropic medication preconception, in pregnancy and postpartum 2017. J Psychopharmacol. 2017;31:519–52.

Byatt N, Deligiannidis KM, Freeman MP. Antidepressant use in pregnancy: a critical review focused on risks and controversies. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2013;127:94–114.

Parikh SV, Segal ZV, Grigoriadis S, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) clinical guidelines for the management of major depressive disorder in adults. II. Psychotherapy alone or in combination with antidepressant medication. J Affect Disord. 2009;117(Suppl 1):S15-25.

Parikh SV, Quilty LC, Ravitz P, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) 2016 clinical guidelines for the management of adults with major depressive disorder: section “METHODS”. Psychological treatments. Can J Psychiatry. 2016;61:524–39.

Quilichini JB, Revet A, Garcia P, et al. Comparative effects of 15 antidepressants on the risk of withdrawal syndrome: a real-world study using the WHO pharmacovigilance database. J Affect Disord. 2022;297:189–93.

Fava GA, Cosci F. Understanding and managing withdrawal syndromes after discontinuation of antidepressant drugs. J Clin Psychiatry. 2019;80:19com12794.

Gabriel M, Sharma V. Antidepressant discontinuation syndrome. CMAJ. 2017;189:E747.

Kessler RC, Bromet EJ. The epidemiology of depression across cultures. Annu Rev Public Health. 2013;34:119–38.

Acknowledgements

Funding

This project and journal fee was funded by Laboratorios Bial, S.A. (Madrid, Spain). However, Laboratorios Bial, S.A. (Madrid, Spain) did not participate in any of the steps of the project or in the preparation of this manuscript.

Medical Writing and/or Editorial Assistance

The authors thank Hector de Paz (Outcomes’10, Castellón de la Plana, Spain) for the coordination of the project and for acting as a facilitator during the nominal groups, Fernando Rico-Villademoros (COCIENTE S.L., Madrid, Spain) for his support in the literature search and preparing a draft of this manuscript, and Isabel San Andrés (Incimed, Madrid, Spain) for performing the literature search. This assistance was funded by Laboratorios Bial, S.A. (Madrid, Spain).

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors criteria for authorship. All authors approved the version to be published and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy of integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Author Contributions

Vicente Villanueva and Julio Bobes were responsible for the study concept. All authors (Vicente Villanueva, Jesús Artal, Clara-Isabel Cabeza-Alvarez, Dulce Campos, Ascensión Castillo, Gerardo Flórez, Manuel Franco-Martin, María Paz García-Portilla, Beatriz G. Giráldez, Francisco Gotor, Luis Gutiérrez-Rojas, Albert Molins Albanell, Gonzalo Paniagua, Luis Pintor, Juan José Poza, Teresa Rubio-Granero, Manuel Toledo, Diego Tortosa-Conesa, Juan Rodríguez-Uranga and Julio Bobes) participated in the consensus group discussion, contributed to the development of the recommendations, as well as reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Disclosures

Vicente Villanueva has received honoraria and/or research funds from Angelini Pharma, Bial, Eisai, of Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Neuraxpharm, Novartis, Nutricia, Takeda, UCB Pharma and Zogenix. Jesús Artal has received honoraria from Janssen, Lundbeck, Rovi, Alter. Dulce Campos has received speaker honorarium from UCB, Eisai; advisory honorarium from Angelini; and travel grants from Jazz Pharmaceutical. Manuel Franco-Martin has received consulting honorarium from Boehringer Ingelheim; speaker honorarium from Lundbeck, Janssen, Rovi, Adamed; researcher of clinical trials from Acadia, Roche, Otsuka, Janssen, Oryzon, Boehringer Ingelheim, Lundbeck, Karuna Therapeutics, Alpha Bioresearch, Stalicla SA, Compass Pathfinder Limited. María Paz García-Portilla has been a consultant to and/or has received honoraria/grants from Alter, Angelini, Cassen-Recordati, Janssen-Cilag, Idorsia, Lundbeck, Otsuka, and SAGE Therapeutics. Beatriz G. Giráldez has received speaker and consulting honorarium from UCB pharma, EISAI, BIAL and Angelini Pharma. Francisco Gotor has been advisory board member for Bial, Eysay, and Lundbeck; has received speaker honorarium from Adamed, Bial, Lundbeck and Janssen. Luis Gutiérrez-Rojas has been speaker for and advisory board member of Janssen-Cilag, Lundbeck, Otsuka, Angelini and Pfizer. Gonzalo Paniagua has received speaker honorarium from Janssen, Otsuka, Ludbeck; and travel grants from Janssen, Otsuka, Ludbeck. Juan José Poza has received speaker honorarium from Adamed, Angelini, Bial, Eisai, Esteve, Glaxo, Jansen, Jazz Pharmaceutical, Neuraxfarm, UCB and Zogenix; and advisory honorarium from Angelini, Bial, Eisai, Jazz Pharmaceutical, UCB and Zogenix. Manuel Toledo has received honoraria and/or research funds from Angelini Pharma, Bial, Eisai, of Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Neuraxpharm, UCB Pharma and Zogenix. Juan Rodríguez-Uranga has been advisory board member for Angelini, UCB, EISAI, GW pharma; has received speaker honorarium from UCB, Angelini, Bial, Eisai, Phiser, Livanova, Novartis; and has received consulting honorarium from Stada, Angelini, UCB, Bial, Eisai. Julio Bobes has received research grants and served as consultant, advisor or speaker within the last 3 years for: AB-Biotics, Acadia Pharmaceuticals, Alkermes, Angelini, Ambrosseti-Angelini, Biogen, Casen Recordati, D&A Pharma, Exeltis, Gilead, Indivior, GW Pharmaceuticals, Janssen-Cilag, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Lundbeck, Otsuka, Pfizer, Roche, Sage Therapeutics, Servier, Shire, Takeda, research funding from the Competitiveness–Centro de Investigación Biomedica en Red area de Salud Mental (CIBERSAM) and Instituto de Salud Carlos III-, Spanish Ministry of Health. Clara-Isabel Cabeza-Alvarez, Ascensión Castillo, Gerardo Flórez, Albert Molins Albanell, Luis Pintor, Teresa Rubio-Granero and Diego Tortosa-Conesa declare no conflict of interest.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This work is based on previously conducted studies and the clinical expertise of the authors in treating patients with epilepsy and/or depression. No new clinical studies were performed by the authors. No patient-specific efficacy or safety data were reported; therefore, institutional review board (IRB)/ethics approval was not required for the consensus recommendations. All panelists were aware of the objectives of the study and verbally agreed to participate in the development and publication of the recommendations.

Data Availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article, as no data sets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Villanueva, V., Artal, J., Cabeza-Alvarez, CI. et al. Proposed Recommendations for the Management of Depression in Adults with Epilepsy: An Expert Consensus. Neurol Ther 12, 479–503 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40120-023-00437-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40120-023-00437-0