Abstract

Introduction

Therapeutic efficacy of disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) for multiple sclerosis (MS) is often hindered by poor persistence and adherence, impacted by patient-perceived efficacy concerns, adverse effects, inconvenience, and forgetfulness. This study measured persistence, adherence, and time to switching to higher-cost therapy among patients with MS initiating teriflunomide, dimethyl fumarate, fingolimod, or diroximel fumarate treatment.

Methods

This retrospective study used Symphony Health US claims data from patients with MS newly initiated on one of four oral DMTs between January and June 2020. Persistence was defined as the duration a patient continued their medication. Adherence was measured using medication possession ratio (MPR); patients with MPR ≥ 80% were considered adherent. Switching was measured by comparing proportions of patients switching and mean time to switch to one of three higher-cost therapies (ocrelizumab, natalizumab, or cladribine). Kaplan–Meier curves assessed persistence. Chi-square tests determined proportions of patients on therapy after 12 months.

Results

A total of 6934 patients newly initiated on oral DMTs met study inclusion criteria (teriflunomide, n = 1968; dimethyl fumarate, n = 3409; diroximel fumarate, n = 616; fingolimod, n = 941). Patients newly initiated on teriflunomide and fingolimod had significantly higher persistence rates after 12 months (60% and 66%, respectively vs 44% dimethyl fumarate and 49% diroximel fumarate; p < 0.0001), and the highest proportion of adherent patients at 6 months (71% and 76%, vs 60% dimethyl fumarate and 58% diroximel fumarate) and 12 months (55% and 59%, vs 40% dimethyl fumarate and 44% diroximel fumarate). Mean time to switching to higher-cost therapies ranged from 247 days (diroximel fumarate to natalizumab) to 342 days (teriflunomide to ocrelizumab), with the highest rate of switching in patients on dimethyl fumarate (7%).

Conclusion

Patients newly initiated on teriflunomide and fingolimod had better real-world persistence and adherence at 6 and 12 months, and longer time to switch to higher-cost therapies, than patients on dimethyl fumarate or diroximel fumarate.

People living with multiple sclerosis (MS for short) can find it difficult to maintain treatment plans. This can impact how well disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) work. This means treatments may not be as effective at controlling symptoms or stop** new symptoms (relapse). In this study, we looked at health records of 6934 previously diagnosed people living with MS in the USA. These people started DMTs for the first time between January and June 2020. Researchers studied how long people continued their treatment (known as persistence) and how often people took their treatment as recommended (adherence). We also studied how many people switched to a more expensive treatment (ocrelizumab, natalizumab, or cladribine). We measured persistence based on how many days people continued their treatment. We measured adherence through the number of people who took their treatment at least 80% of the time. After 1 year, more people who took teriflunomide and fingolimod continued treatment than people on dimethyl fumarate or diroximel fumarate. These people were also more likely to follow their treatment plan. People taking dimethyl fumarate were most likely to switch to a more expensive treatment. On average, people who changed to a more expensive treatment did so after around 8 months. In this study, we found that people with MS who started teriflunomide or fingolimod for the first time were more likely to continue treatment and take treatment as recommended than those on dimethyl fumarate or diroximel fumarate. They also took longer to switch to a more expensive treatment.

AbstractSection Graphical abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this study? |

Disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) underpin current treatment approaches for multiple sclerosis (MS), and can reduce the frequency and severity of relapses, delay disease progression, and limit new disease activity. |

This study is the first to measure persistence, adherence, and time to switching to higher-cost therapies among patients initiating the oral DMTs teriflunomide, dimethyl fumarate, diroximel fumarate, and fingolimod in a real-world setting. |

What was learned from this study? |

Medication persistence and adherence were higher among patients newly initiated on teriflunomide and fingolimod than with patients initiated on dimethyl fumarate and diroximel fumarate. |

The average time to switching ranged from 247 to 342 days. The highest rate of switching was found among patients on dimethyl fumarate, followed by diroximel fumarate, and fingolimod and teriflunomide with the same rate. |

Increased medication persistence and adherence are important factors in achieving therapeutic goals in MS and their clinical and economic benefits are well documented. Our findings can inform and support improved treatment-related decision-making among patients and providers. |

Digital Features

This article is published with digital features, including a graphical abstract, to facilitate understanding of the article. To view digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.20654583.

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic, immune-mediated neurodegenerative disease of the central nervous system that causes inflammation, demyelination, and axonal degeneration [1, 2]. MS is estimated to affect over 2.8 million people globally and 400,000 people in the USA [3, 4]. Although the course of MS is highly heterogeneous, most patients experience episodes of new or worsening neurological deficits and accumulation of unremitting disability which are both present from the very earliest stages of the disease [1, 5]. Relapsing–remitting MS (RRMS) is the most common form of MS, accounting for roughly 85% of cases [1]. RRMS is characterized by relapses, in which symptoms flare up, followed by periods of remission [1].

Although there is no curative treatment for MS, several disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) have been developed to reduce the frequency and severity of relapses, delay disease progression, and limit new disease activity [6,7,8]. There are currently more than 15 approved therapies available, with various routes of administration (injection, intravenous infusion, and oral), modes of action, and dosing schedules [5]. With so many therapies available, the appropriate choice for a given patient will depend on several considerations, including level of disease activity, disease progression, medication-related factors (tolerability profile, administration method, efficacy, and cost), and patient characteristics and preferences [9].

For medications to reach optimal therapeutic efficacy, they must be taken as prescribed. However, like those with many chronic illnesses, patients with MS may struggle with persistence (the duration of time from initiation to discontinuation of therapy) and adherence (the degree to which they follow their treatment plan) [7, 10,11,12]. Factors impacting persistence and adherence of MS DMTs include patient-perceived lack of efficacy, adverse effects, inconvenience, and forgetfulness [7, 12]. Real-world studies have shown that nonpersistence and nonadherence to DMTs can lead to negative clinical and economic outcomes for patients with MS, including higher rates of relapse, disease progression, hospitalization, and increased medical costs [7, 13]. Furthermore, patients who are dissatisfied with their treatment are more likely to switch therapies. Previous studies have shown that up to 30% of patients with MS switch to an alternative DMT at least once within 2 years of initiating treatment [14, 15], with lack of efficacy and adverse effects cited as the most common reasons for switching [16]. As with nonpersistence and nonadherence, DMT switching is associated with higher rates of relapse and healthcare costs [15,16,17].

Previous studies have compared treatment persistence and adherence between available oral DMTs excluding diroximel fumarate, and injectable DMTs, with results suggesting that oral DMTs have improved persistence and adherence. A retrospective study of hospitalization and outpatient data from 10,240 patients with MS newly initiated on a first-line DMT for RRMS reported significantly higher persistence and adherence with oral DMTs (teriflunomide and dimethyl fumarate) than injectable DMTs (interferons and glatiramer acetate) [9]. Another retrospective database study also found that patients who received injectable DMTs discontinued significantly sooner than oral DMT users [18].

Oral DMTs are convenient and easy to administer and have similar or superior efficacy to platform injectable therapies [6, 19]. Recent studies suggest that orally administered products are preferred over all parenteral routes of administration [20,21,22]. The first oral agents to treat RRMS were approved in the USA between 2010 and 2013 and include teriflunomide, dimethyl fumarate, and fingolimod [19, 23,24,25]. A fourth oral treatment, diroximel fumarate was approved in the USA in 2019 and recently in the European Union (EU) in 2021 for the treatment of RRMS [26]. Diroximel fumarate is converted to monomethyl fumarate, the pharmacologically active metabolite of dimethyl fumarate. As a result of diroximel fumarate’s chemical structure, it may have a similar efficacy and safety profile to dimethyl fumarate with fewer gastrointestinal (GI) tolerability issues [27]. The extent to which diroximel fumarate may differ in treatment persistence and adherence to other oral DMTs is inexplicit and needs to be confirmed in real-world settings.

Previous real-world studies have measured persistence and adherence to teriflunomide, dimethyl fumarate, and fingolimod; however, there is a lack of real-world evidence on diroximel fumarate. Therefore, the objective of this study was to measure persistence, adherence, and time to switching to a higher-cost therapy among patients with MS initiating treatment with these four oral DMTs.

Methods

Data Source

This retrospective analysis was conducted using data from the Symphony Health US database. The Symphony Health database is one of the largest integrated repositories of healthcare data in the USA, capturing more than 93% of prescriptions dispensed and housing data from more than 317 million active individual patients. The database includes medical, hospital, and prescription claims across all payment types, enhanced with diagnostic, lab, and registry data; demographic and affiliation data; and e-health record data. This study is based on information from an existing retrospective claims database and is exempt from review or approval by institutional review boards, ethics committees, or informed consent. Data were de-identified and comply with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act and the Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Data sets were obtained under contract with Symphony Health to perform the analyses for this study.

Patient Selection

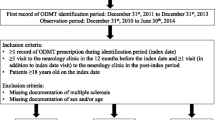

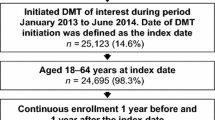

Patients who were newly initiated on teriflunomide, dimethyl fumarate, diroximel fumarate, or fingolimod within the qualifying time period (January 1, 2020 through June 30, 2020) were identified. Patients were required to have at least one diagnosis of MS (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification code [ICD-9-CM] 340 OR [ICD-10-CM] G35) between January 1, 2016 and January 1, 2020 and at least one diagnosis of MS during the qualifying time period. Evidence of prescription or medical claims activity in both the 2020 and 2021 calendar years was also required. Patients who had evidence of using more than one study drug were assigned to the drug that they initiated first during the time period of interest. There was no restriction in age for patients. Patients were excluded if they were treated with teriflunomide, dimethyl fumarate, diroximel fumarate, or fingolimod within 12 months before the qualifying time period. Patients were followed for 12 months from the start of the initial treatment during the qualifying period. Patient selection and study inclusion and exclusion criteria are summarized in Fig. 1. The National Drug Codes and procedure codes are listed in Supplementary Material Tables 1 and 2, respectively.

Study Measures

Baseline Demographics

Patient demographics were collected for each patient and included age, sex, age at MS diagnosis, and treatment history (including treatment-naïve and previous DMT use).

Outcome Measures

Outcome measures included treatment persistence, treatment adherence, and time to switching to higher-cost therapies. Persistence was measured by the duration a patient continued on their medication, as defined by having their prescription dispensed with less than a 30-day gap (the “grace period”) during the 12-month follow-up period from treatment initiation. Patients who exceeded the 30-day grace period to refill their prescriptions were deemed nonpersistent. If nonpersistent patients reinitiated treatment during the study period, they were reestablished within the product’s persistence curve. A grace period of 30 days was established because this reflects the average monthly supply for treatments.

Adherence was measured using the medication possession ratio (MPR), a commonly used measure in administrative claims studies, which assesses the number of days covered by supply of the medication over a fixed length of time. The MPR was calculated for both 6- and 12-month durations by dividing the total days of medication supply in the first 6 and 12 months of treatment by 183 and 366, respectively. Maximum adherence was capped at 1 for those with over 183 or 366 days of medication filled. Mean adherence to each drug was calculated at 6 and 12 months, regardless of persistence status. Using a commonly applied threshold [13, 28], we considered patients with MPR ≥ 80% to be adherent to their index treatment and patients with MPR < 80% to be nonadherent.

Switching was measured by comparing the proportion of patients who switched DMTs and the mean time to switch from each of the four index therapies (teriflunomide, dimethyl fumarate, diroximel fumarate, or fingolimod) to one of three higher-cost therapies (ocrelizumab, natalizumab, or cladribine). Patients were followed for a minimum of 16 months and a maximum of 22 months (from treatment initiation until October 31, 2021).

Statistical Analyses

Patient demographics were stratified by treatment group (teriflunomide, dimethyl fumarate, diroximel fumarate, or fingolimod) and summarized by percentage or mean ± standard deviation. Kaplan–Meier curves were used to assess persistence on each of the four study drugs, and a chi-square test was performed using the PROC FREQ procedure (World Programming System; World Programming, Hampshire, UK) to determine the proportion of patients on therapy after 12 months for each pair of drugs. No statistical tests were performed to analyze differences in adherence or switching and no adjustments were made for confounding variables.

Results

Patient Characteristics

The baseline characteristics of the 6934 patients included in this study are shown in Table 1. The majority of patients were on dimethyl fumarate (49%; n = 3409), followed by teriflunomide (28%; n = 1,968), fingolimod (14%; n = 941), and diroximel fumarate (9%; n = 616). The mean age for the treatment cohorts ranged from 44 to 51 years (population mean, 48 ± 12.6), whereas the mean age at MS diagnosis ranged from 39.1 to 45.8 years (population mean, 43 ± 11.5). The majority of patients were female (77%). A total of 59% of patients were treatment-naïve (no previous experience with a DMT), whereas 41% of patients had used a DMT (excluding the four study drugs) on one or more occasions in the last year. The fingolimod and dimethyl fumarate treatment groups had the highest proportion of treatment-naïve patients (69% and 68%, respectively), followed by teriflunomide (46%) and diroximel fumarate (38%).

Therapy Persistence

Teriflunomide and fingolimod patients had the highest persistence rates (60% and 66%, respectively), whereas dimethyl fumarate and diroximel fumarate patients had the lowest persistence rates (44% and 49%, respectively) after 12 months (Fig. 2). The persistence rates for fingolimod and teriflunomide patients were statistically significantly different from both diroximel fumarate and dimethyl fumarate patients at 6 and 12 months (p < 0.001 in all cases).

Therapy Adherence

The proportion of patients adherent (MPR ≥ 80%) to teriflunomide and fingolimod at 6 months (71% and 76%, respectively) and 12 months (55% and 59%, respectively) was higher than the proportion of patients adherent to dimethyl fumarate and diroximel fumarate at 6 months (60% and 58%, respectively) and 12 months (40% and 44%, respectively) (Fig. 3).

Switching to a Higher-Cost Therapy

Patients newly initiated on dimethyl fumarate had the highest rate of switching to a higher-cost therapy (7%; n = 233), followed by patients newly initiated on diroximel fumarate (6%; n = 37), fingolimod (5%; n = 51), and teriflunomide (5%; n = 103).

The mean time to switching to higher-cost therapies in patients newly initiated on treatment with one of the four oral DMTs ranged from 247 days (diroximel fumarate to natalizumab) to 342 days (teriflunomide to ocrelizumab) (Fig. 4). Teriflunomide had the longest mean time to switch to ocrelizumab (342 days) and cladribine (337 days), while the fumarates had the shortest mean time to switch to ocrelizumab (diroximel fumarate, 283 days) and cladribine (dimethyl fumarate, 294 days). The mean time to switch to natalizumab was longest from fingolimod (306 days) and the shortest from diroximel fumarate (247 days).

Discussion

This retrospective real-world database study is the first to measure persistence, adherence, and time to switching to a higher-cost therapy (ocrelizumab, natalizumab, or cladribine) among patients with MS initiating treatment with the recently approved medication diroximel fumarate alongside three commonly used oral DMTs (teriflunomide, dimethyl fumarate, and fingolimod).

In this study, patients with MS newly initiated on teriflunomide and fingolimod had higher persistence rates and mean adherence at 6 and 12 months than patients treated with dimethyl fumarate and diroximel fumarate. Patients newly initiated on the fumarates (dimethyl fumarate and diroximel fumarate) had a larger percentage of patients switching and a shorter time to switching to a higher-cost therapy than patients newly initiated on the other oral DMTs.

Our findings are generally consistent with results from previous real-world studies of persistence and adherence to DMTs in patients with MS [9, 29]. A retrospective French database study analyzed adherence to first-line DMTs in 10,240 patients with RRMS newly initiating therapy [9]. Persistence and adherence were found to be higher overall in patients initiating therapy with an oral DMT, with better persistence observed in patients receiving teriflunomide than those receiving dimethyl fumarate. Likewise, a retrospective US database study of 1498 patients newly prescribed oral DMTs for MS reported significantly greater persistence and adherence among patients receiving fingolimod compared with patients receiving other oral DMTs over a 12-month period [6].

Nonpersistence and nonadherence can occur for a variety of reasons, including administration method, efficacy, tolerability profile, cost, and treatment satisfaction[9]. Additionally, previous adherence studies have reported greater DMT adherence for patients with RMS with once daily administration over other dosing schemes [6, 9, 29], which may partially explain the higher adherence observed for teriflunomide and fingolimod (administered once daily) versus dimethyl fumarate and diroximel fumarate (administered twice daily) in this study.

Regarding tolerability, among oral DMTs for MS, the fumarates are associated with GI adverse events that can lead to premature discontinuations [30,31,32]. A systematic review and meta-analysis that compiled data from 12,380 patients treated with dimethyl fumarate found that GI symptoms were the most common adverse event (occurring in 36% of patients), as well as the most commonly stated reason for discontinuing treatment (9% of all patients) [30]. A recent randomized, double-blind, phase 3 study demonstrated fewer GI tolerability issues with diroximel fumarate compared with dimethyl fumarate. Among the 500 patients included in the study, lower rates of GI adverse events were experienced with diroximel fumarate than dimethyl fumarate (34.8% vs 49.0%) and lower discontinuation rates due to GI adverse effects (1.6% vs 5.6%) [27]. However, findings from our real-world study of 6934 patients suggest that persistence and adherence among patients receiving diroximel fumarate and dimethyl fumarate were similar.

In addition to medication tolerability, greater satisfaction with treatment has been associated with higher adherence across a range of chronic conditions [33], including RRMS [34]. A large, global, phase 4 study measuring patient-reported outcomes (treatment satisfaction, disability, tolerability, clinical effectiveness, and quality of life) using the Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire for Medication (TSQM) in patients with MS treated with teriflunomide reported high levels of treatment satisfaction, including patients who switched from other oral or injectable DMTs [35]. In addition, teriflunomide maintained effectiveness over the course of the study on two patient-reported disability scales [35]. Although approximately 82% of patients experienced adverse events, these were mostly mild to moderate in nature and led to treatment discontinuation in only a subset (10.9%) of patients [35].

There are limited real-world studies investigating the rates and reasons of switching DMTs. Our switching analyses focused on higher-cost agents given switching due to efficacy concerns, the most common reason for switching in MS, generally results in the choice of a high efficacy, thus often higher-cost, therapy [16, 36]. A retrospective, multicenter, Italian study of data from 2954 patients newly diagnosed with RRMS found that 48% of patients switched therapy within 3 years, with poor efficacy listed as the most common reason for switching [37]. Switching may also vary with symptom severity. A cross-sectional German study of 595 patients with MS reported higher rates of switching to an alternate DMT in patients with mild to moderate MS (54.3%) compared with patients with active or highly active MS (43.5%) [16].

Treatment persistence and adherence can result in better clinical and economic outcomes, including lower rates of relapses, risks for MS-related hospitalization, and MS-related medical costs [13, 38, 39]. A retrospective claims database study of 12,431 patients with MS calculated the predicted mean cost savings among adherent patients in the 12 months after initiation of a DMT [13]. They reported a total reduction in medical (nondrug) costs per patient of $5815.47 (− 41.7%), hospitalization costs of $1953.01 (− 58.5%), emergency department costs of $171.40 (− 46.9%), and outpatient admission costs of $2801.63 (− 32.9%). Likewise, studies have shown that patients who switched or discontinued their DMT had higher medical utilization and costs, suggesting that disruptions in therapy may result in serious unintended consequences [17, 40].

Treatments that overcome some of the challenges associated with MS therapies (side effects, lack of treatment satisfaction, and perceived effectiveness) may improve persistence and adherence, delay time to switch, and consequently result in better therapeutic outcomes and reduced costs.

Limitations

Our results were obtained from a claims database, which has several inherent limitations. Claims data provide only an indirect measure of medication-taking behavior, and details on the patient’s clinical presentation and demographic characteristics are constrained to what can be extracted from health records. To obtain the largest and most representative sample, we included all patients who initiated treatment on the four study products during the study period, which included unequal numbers of patients in each analysis. However, unequal numbers across analyses were a necessary component of capturing patients who switched to higher-cost DMTs. Additionally, our outcomes are largely reported using descriptive measures, and no adjustments were made for possible confounding variables, such as any potential baseline differences between groups, e.g., age or MS severity. Other factors which may further contextualize our findings, such as information on treatment efficacy, and reasons for nonpersistence, nonadherence, and switching were not available in the database.

Conclusion

This real-world claims data study demonstrates that patients with MS newly initiated on teriflunomide and fingolimod had better persistence and adherence at 6 and 12 months than patients treated with dimethyl fumarate or diroximel fumarate. Patients newly initiated on the fumarates (dimethyl fumarate and diroximel fumarate) were more likely to switch and had a shorter time to switching to a higher-cost therapy than patients newly initiated on teriflunomide and fingolimod. Given the importance of treatment persistence, adherence, and time to switching on clinical and economic outcomes for patients with MS, our findings can be used to inform treatment decision-making by healthcare providers, payers, and patients.

References

Goldberg MM. Multiple sclerosis review. PT. 2012;37:175–84.

Bandari DS, Sternaman D, Chan T, Prostko CR, Sapir T. Evaluating risks, costs, and benefits of new and emerging therapies to optimize outcomes in multiple sclerosis. J Manag Care Pharm. 2012;18:1–17.

Global Burden of Disease Study Group. Global, regional, and national burden of neurological disorders, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2019;18:459–80.

Walton C, King R, Rechtman L, et al. Rising prevalence of multiple sclerosis worldwide: Insights from the Atlas of MS, third edition. Mult Scler. 2020;26:1816–1821.

Engmann NJ, Sheinson D, Bawa K, Ng CD, Pardo G. Persistence and adherence to ocrelizumab compared with other disease-modifying therapies for multiple sclerosis in US commercial claims data. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2021;27:639–49.

Johnson KM, Zhou H, Lin F, Ko JJ, Herrera V. Real-world adherence and persistence to oral disease-modifying therapies in multiple sclerosis patients over 1 year. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2017;23:844–52.

Menzin J, Caon C, Nichols C, White LA, Friedman M, Pill MW. Narrative review of the literature on adherence to disease-modifying therapies among patients with multiple sclerosis. J Manag Care Pharm. 2013;19:S24-40.

National Multiple Sclerosis Society. Disease-modifying therapies for MS. https://nms2cdn.azureedge.net/cmssite/nationalmssociety/media/msnationalfiles/brochures/brochure-the-ms-disease-modifying-medications.pdf. Accessed 22 Mar 2022.

Vermersch P, Suchet L, Colamarino R, Laurendeau C, Detournay B. An analysis of first-line disease-modifying therapies in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis using the French nationwide health claims database from 2014–2017. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2020;46: 102521.

Cramer JA, Roy A, Burrell A, et al. Medication compliance and persistence: terminology and definitions. Value Health. 2008;11:44–7.

Riñon A, Buch M, Holley D, Verdun E. The MS Choices Survey: findings of a study assessing physician and patient perspectives on living with and managing multiple sclerosis. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2011;5:629–43.

Pardo G, Pineda ED, Ng CD, Bawa KK, Sheinson D, Bonine NG. Adherence to and persistence with disease-modifying therapies for multiple sclerosis over 24 months: a retrospective claims analysis. Neurol Ther. 2022;11:337–51.

Burks J, Marshall TS, Ye X. Adherence to disease-modifying therapies and its impact on relapse, health resource utilization, and costs among patients with multiple sclerosis. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2017;9:251–60.

Degli Esposti L, Piccinni C, Sangiorgi D, et al. Changes in first-line injectable disease-modifying therapy for multiple sclerosis: predictors of non-adherence, switching, discontinuation, and interruption of drugs. Neurol Sci. 2017;38:589–94.

Nicholas J, Ko JJ, Park Y, et al. Assessment of treatment patterns associated with injectable disease-modifying therapy among relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis patients. Mult Scler J Exp Transl Clin. 2017;3:2055217317696114.

Mäurer M, Tiel-Wilck K, Oehm E, et al. Reasons to switch: a noninterventional study evaluating immunotherapy switches in a large German multicentre cohort of patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2019;12:1756286419892077.

Freeman L, Kee A, Tian M, Mehta R. Retrospective claims analysis of treatment patterns, relapse, utilization, and cost among patients with multiple sclerosis initiating second-line disease-modifying therapy. Drugs Real World Outcomes. 2021;8:497–508.

Agashivala N, Wu N, Abouzaid S, et al. Compliance to fingolimod and other disease modifying treatments in multiple sclerosis patients, a retrospective cohort study. BMC Neurol. 2013;13:138.

Garg N, McCarthy M, Karmarkar A. Oral therapies for MS. Pract Neurol. 2019;Nov–Dec.

Hincapie AL, Penm J, Burns CF. Factors associated with patient preferences for disease-modifying therapies in multiple sclerosis. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2017;23:822–30.

Wilson LS, Loucks A, Gipson G, et al. Patient preferences for attributes of multiple sclerosis disease-modifying therapies: development and results of a ratings-based conjoint analysis. Int J MS Care. 2015;17:74–82.

Lynd LD, Traboulsee A, Marra CA, et al. Quantitative analysis of multiple sclerosis patients’ preferences for drug treatment: a best-worst scaling study. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2016;9:287–96.

Genzyme Overview of Aubagio (teriflunomide) tablets, for oral use. https://products.sanofi.us/Aubagio/Aubagio.pdf. Accessed 22 Mar 2022.

Biogen Tecfidera (dimethyl fumarate) delayed-release capsules, for oral use. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2013/204063lbl.pdf. Accessed 22 Mar 2022.

Novartis US Gilenya (fingolimod) capsules. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2012/022527s008lbl.pdf. Accessed 22 Mar 2022.

Alkermes Vumerity (diroximel fumarate) delayed-release capsules, for oral use. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2019/211855s000lbl.pdf. Accessed 22 Mar 2022.

Naismith RT, Wundes A, Ziemssen T, et al. Diroximel fumarate demonstrates an improved gastrointestinal tolerability profile compared with dimethyl fumarate in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: results from the randomized, double-blind, phase III EVOLVE-MS-2 study. CNS Drugs. 2020;34:185–96.

Mardan J, Hussain MA, Allan M, Grech LB. Objective medication adherence and persistence in people with multiple sclerosis: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2021;27:1273–95.

Lahdenperä S, Soilu-Hänninen M, Kuusisto HM, Atula S, Junnila J, Berglund A. Medication adherence/persistence among patients with active multiple sclerosis in Finland. Acta Neurol Scand. 2020;142:605–12.

Liang G, Chai J, Ng HS, Tremlett H. Safety of dimethyl fumarate for multiple sclerosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2020;46: 102566.

Min J, Cohan S, Alvarez E, et al. Real-world characterization of dimethyl fumarate-related gastrointestinal events in multiple sclerosis: management strategies to improve persistence on treatment and patient outcomes. Neurol Ther. 2019;8:109–19.

Hoogendoorn A, Avery TD, Li J, Bursill C, Abell A, Grace PM. Emerging therapeutic applications for fumarates. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2021;42:239–54.

Barbosa CD, Balp MM, Kulich K, Germain N, Rofail D. A literature review to explore the link between treatment satisfaction and adherence, compliance, and persistence. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2012;6:39–48.

Haase R, Kullmann JS, Ziemssen T. Therapy satisfaction and adherence in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: the THEPA-MS survey. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2016;9:250–63.

Coyle PK, Khatri B, Edwards KR, et al. Patient-reported outcomes in relapsing forms of MS: real-world, global treatment experience with teriflunomide from the Teri-PRO study. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2017;17:107–15.

Patti F, Chisari CG, D’Amico E, et al. Clinical and patient determinants of changing therapy in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (SWITCH study). Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2020;42: 102124.

Saccà F, Lanzillo R, Signori A, et al. Determinants of therapy switch in multiple sclerosis treatment-naïve patients: a real-life study. Mult Scler. 2019;25:1263–72.

Ivanova JI, Bergman RE, Birnbaum HG, Phillips AL, Stewart M, Meletiche DM. Impact of medication adherence to disease-modifying drugs on severe relapse, and direct and indirect costs among employees with multiple sclerosis in the US. J Med Econ. 2012;15:601–9.

Tan H, Cai Q, Agarwal S, Stephenson JJ, Kamat S. Impact of adherence to disease-modifying therapies on clinical and economic outcomes among patients with multiple sclerosis. Adv Ther. 2011;28:51–61.

Reynolds MW, Stephen R, Seaman C, Rajagopalan K. Healthcare resource utilization following switch or discontinuation in multiple sclerosis patients on disease modifying drugs. J Med Econ. 2010;13:90–8.

Acknowledgements

Funding

This study and the journal’s Rapid Service Fee were funded by Sanofi.

Editorial Assistance

Editorial support was provided by Elevate Scientific Solutions (Tina Peckmezian, PhD, and Renee Granger, PhD) and was funded by Sanofi.

Author Contributions

All authors were involved in the study concept and design. All authors critically revised the manuscript.

Disclosures

This research was funded by Sanofi. Lita Araujo, Svend S Geertsen, Allen Amedume, Keiko Higuchi and Janneke van Wingerden are employed by Sanofi and may hold stock or stock options.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This study is based on information from an existing retrospective claims database and is exempt from review or approval by institutional review boards, ethics committees, or informed consent. Data were de-identified and comply with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act and the Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Data sets were obtained under contract with Symphony Health to perform the analyses for this study.

Data Availability

The data sets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available because they are proprietary administrative health claims data owned by Symphony Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Araujo, L., Geertsen, S.S., Amedume, A. et al. Persistence, Adherence, and Switching to Higher-Cost Therapy in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis Initiating Oral Disease-Modifying Therapies: A Retrospective Real-World Study. Neurol Ther 11, 1735–1748 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40120-022-00404-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40120-022-00404-1