Abstract

Introduction

This analysis evaluated the treatment satisfaction of Japanese patients receiving galcanezumab (GMB) as a preventive medication for episodic migraine (4–14 monthly migraine headache days).

Methods

This phase 2, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study enrolled patients aged 18–65 years at 40 centers in Japan. Patients were randomized 2:1:1 to receive monthly subcutaneous injections of placebo (PBO, n = 230), GMB 120 mg (n = 115), or GMB 240 mg (n = 114) for 6 months. Patients’ experience with treatment was measured using the Patient Global Impression of Severity (PGI-S), Patient Global Impression of Improvement (PGI-I), and Patient Satisfaction with Medication Questionnaire-Modified (PSMQ-M) scales. PGI-S was administered at baseline and months 1–6, PGI-I at months 1–6, and PSMQ-M at months 1 and 6. Prespecified analyses were differences between GMB and PBO in PGI-I and the change from baseline in PGI-S, and evaluating positive responses for the PGI-I and PSMQ-M.

Results

Average change ± SE from baseline across months 1–6 was − 0.09 ± 0.05 (PBO), − 0.17 ± 0.07 (GMB 120 mg, p = 0.33), and − 0.30 ± 0.07 (GMB 240 mg, p = 0.013) for PGI-S. Average PGI-I across months 1–6 was 3.39 ± 0.05 (PBO), 2.55 ± 0.07 (GMB 120 mg, p < 0.05), and 2.71 ± 0.07 (GMB 240 mg, p < 0.05). Reductions of 2.8–3.0 monthly migraine headache days corresponded to 25–31% higher positive PGI-I response rates with GMB compared with PBO. Positive PSMQ-M response rates for satisfaction and preference were statistically significantly higher for GMB compared with PBO (odds ratio [95% confidence interval], all p < 0.05 vs. PBO): satisfaction GMB 120 mg (3.142 [1.936–5.098]) and GMB 240 mg (3.924 [2.417–6.369]), and preference GMB 120 mg (3.691 [2.265–6.017]) and GMB 240 mg (3.510 [2.180–5.652]).

Conclusion

Japanese patients with episodic migraine receiving preventive treatment with GMB are significantly more satisfied than those receiving PBO.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT02959177 (registered November 7, 2016).

Graphical Plain Language Summary

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this study? |

Currently, the level of patient satisfaction with preventive treatments for migraine in Japan is unknown. |

We investigated the impact of preventive treatment with galcanezumab on Japanese patients with migraine, by measuring their perceptions of disease severity, improvement in symptoms, treatment satisfaction, medication preference, and side effects. |

What was learned from the study? |

Japanese patients with episodic migraine had higher treatment satisfaction with galcanezumab compared with placebo. |

Patients treated with galcanezumab reported a greater reduction in disease severity and greater improvement in symptoms than patients who received placebo. |

Japanese patients receiving galcanezumab tended to be more satisfied with the medication, and more likely to prefer it to their previous medication, than patients receiving placebo. |

Digital Features

This article is published with digital features, including a summary slide and graphical plain language summary, to facilitate understanding of the article. To view digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14054621.

Introduction

Migraine is a common and chronic neurological disease, which has a substantial impact on function and quality of life [1, 2]. Preventive therapy for people with migraine is indicated when migraine attack frequency is high and/or migraine attacks substantially affect daily life [3, 4]. Numerous preventive medications for migraine have been shown to reduce the number of monthly migraine headache days [5,6,7,8,9] and improve health-related quality of life (QoL) [10,11,12,13]. Despite this, preventive medication is often not prescribed to those who would benefit from it [3]. For those who are prescribed preventive medication, response to treatment can be highly individual [6]. Patients dissatisfied with preventive treatment will likely discontinue or switch medications [14], so patient satisfaction is an important determinant of effective preventive treatment for migraine.

Galcanezumab (GMB), a preventive medication for migraine, is a humanized IgG4 monoclonal antibody that binds calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP), preventing its biological activity without binding the CGRP receptor. GMB is effective in reducing monthly migraine headache days [7, 8], reducing total pain burden [15], and improving QoL for people with migraine [11,12,13]. Efficacy and QoL improvements of GMB are generally consistent across age groups and migraine headache frequencies [16, 17]. A majority of patients (more than 69%) treated with GMB in an open-label study across five countries responded positively to the medication in terms of overall satisfaction, preference over previous medications, and reduced impact from side effects [18].

In Japan, the prevalence of migraine is estimated to be between 6.0% and 8.4% of the population [19, 20], similar to that in other East Asian countries [21]. Among Japanese people with migraine who seek medical care, 42–69% have used preventive treatment at least once [22]. Despite this relatively large proportion of individuals receiving preventive treatment for migraine, few studies have explicitly addressed Japanese patients’ satisfaction with migraine treatment [19, 20, 22]. Therefore, a knowledge gap exists.

This manuscript describes prespecified analyses of the treatment experience of Japanese patients with episodic migraine (EM; i.e., 4–14 migraine headache days per month) treated with GMB (120 mg or 240 mg) or placebo (PBO) for 6 months in a randomized, double-blind, PBO-controlled clinical trial [23]. We hypothesized that GMB would improve patient satisfaction with their medication, in combination with reducing disease severity and improving symptoms, compared with PBO.

Methods

Study Design

The study design has been reported previously [23]. Briefly, this was a phase 2, four-period, randomized, double-blind, PBO-controlled study of GMB in Japanese patients with EM (NCT02959177). Following protocol approval by local independent ethics review boards and written informed consent from the participants, the study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, the International Council for Harmonisation Guideline for Good Clinical Practice, and applicable laws and regulations at 40 sites in Japan between December 2016 and January 2019.

The four periods of the study comprised a screening period, including full clinical assessment and washout of preventive treatments for migraine for at least 30 days; a baseline period to confirm patient eligibility and establish baseline number of migraine headache days; a 6-month, randomized, double-blind, PBO-controlled treatment phase; and a 4-month washout and follow-up phase. This analysis focuses on patient satisfaction during the 6-month treatment phase.

Study Population

Eligible patients had to have onset of migraine with or without aura before age 50 years and occurring at least 1 year before entering the study, as well as a migraine frequency of 4–14 monthly migraine headache days with at least two attacks per month. Monthly migraine headache days were defined as a calendar day on which a migraine headache or probable migraine headache occurred. Patients currently taking preventive treatments for migraine were not eligible for enrollment in the study unless they stopped prior preventive treatments and went through a washout period of at least 30 days. Other ineligible patients were those who had a higher monthly frequency of headache days (at least 15 monthly migraine headache days during the 3 months before the screening period) or had chronic migraine. Additional exclusion criteria have been previously reported [23].

Treatment Protocol

As previously described [23], patients were randomized (2:1:1) to one of three treatment groups, receiving PBO, GMB 120 mg, or GMB 240 mg. Treatments were administered once a month by subcutaneous injection. A loading dose of 240 mg was given at the first injection (month 0) to patients receiving GMB 120 mg.

Outcome Measures

Patients’ experience of GMB treatment was measured using three scales. The Patient Global Impression of Severity (PGI-S) and Patient Global Impression of Improvement (PGI-I) scales have been developed and used in many conditions/diseases to assess patient-reported severity and health improvements [7, 8, 24,25,26,27]. The PGI-S scale ranges from a score of 1 (“not at all ill”) to 7 (“extremely ill”), and the PGI-I scale ranges from a score of 1 (“very much better”) to 7 (“very much worse”). The PGI-S was measured at baseline (month 0) and at each monthly visit (months 1–6). The PGI-I was measured at each monthly visit (months 1–6).

The third scale was the Patient Satisfaction with Medication Questionnaire-Modified (PSMQ-M), which assesses patients’ levels of satisfaction with medication [28]. The PSMQ-M is a self-rated scale, which has been used in one previous open-label study of GMB [18]. It assesses three items related to clinical treatment over the previous 4 weeks: satisfaction, preference, and side effects. Satisfaction with the current medication was rated from “very unsatisfied” to “very satisfied”. Preference, in relation to previous medications used, was rated from “much rather prefer my previous medication” to “much rather prefer the medication administered to me during the study”. Side effects, in relation to previous preventive medications used, were rated from “significantly more side effects” to “significantly less side effects.” The PSMQ-M was administered at months 1 and 6.

Statistical Analysis

Mean changes from baseline to each visit for PGI-S were assessed using a restricted maximum likelihood (REML)-based mixed-model repeated measures (MMRM) technique and are reported as least squares (LS) means ± standard error (SE). The PGI-S MMRM analysis included fixed categorical effects (treatment, month, the baseline number of monthly migraine headache days [< 8, ≥ 8], and treatment-by-month interaction) and continuous fixed covariates (baseline value and baseline-by-month interaction). The PGI-I raw values for each visit were also analyzed using a MMRM technique, including the same fixed categorical effects (treatment, month, the baseline number of monthly migraine headache days [< 8, ≥ 8], and treatment-by-month interaction), with PGI-S baseline value and PGI-S baseline-by-month interaction included as continuous fixed covariates. PGI-I results are reported as LS means ± SE. For each treatment group, frequency tables of PGI-I score and PGI-S change from baseline at each month were generated and summarized as frequency heatmaps.

An analysis of positive PGI-I responses explored the relationship between PGI-I and monthly migraine headache days (the primary efficacy measure [23]) using conditional expectation. Positive PGI-I responses were defined as “very much better” and “much better.” The analysis translated the difference in the primary efficacy measure (monthly migraine headache days for months 1–6) between treatment groups into the difference in the positive PGI-I response rate (month 6), resulting in a measure of clinical importance (improvement in symptoms) that allowed comparison of treatment benefit. The estimated positive PGI-I response rate in month 6 was calculated as the conditional expectation E[Y120 − Y0|(− 1)[X120 − X0] = Δ] for GMB 120 mg, and E[Y240 − Y0|( − 1)[X240 − X0] = Δ] for GMB 240 mg. Y0, Y120, and Y240 are the positive PGI-I response rates at month 6 for PBO, GMB 120 mg, and GMB 240 mg, respectively. X0, X120, and X240 are overall changes from baseline in monthly migraine headache days (average of months 1–6) for PBO, GMB 120 mg, and GMB 240 mg, respectively. Δ is the prespecified difference in monthly migraine headache days between GMB 120 mg (or GMB 240 mg) and PBO. For computational purposes, we set Δ as integer values. For GMB 120 mg, monthly migraine headache days were reduced on average by 3.0 per month vs. PBO [23]; therefore, Δ was set at 3. For GMB 240 mg, monthly migraine headache days were reduced on average by 2.8 per month vs. PBO [23]; therefore, Δ was set at 2 or 3. The 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for this analysis were generated using a nonparametric Monte Carlo bootstrap (1000 replications). This analysis was previously used for the tadalafil benign prostatic hyperplasia new drug application in Japan [29].

Three analyses of the PSMQ-M data were conducted: a descriptive summary of each item (satisfaction, preference, and side effects) for months 1 and 6; a descriptive summary of the positive PSMQ-M responses in months 1 and 6; and a logistic regression analysis of the month 6 positive responses. Positive PSMQ-M responses were defined as follows: for satisfaction, reports of “somewhat satisfied” or “very satisfied”; for preference, reports of “much prefer study medication” or “prefer study medication”; and for side effects, reports of “significantly less side effects” or “less side effects” than their previous medication. The logistic regression model included the categorical effects of treatment and baseline number of monthly migraine headache days (< 8, ≥ 8).

No adjustments for multiplicity were made among arms, time points, and analyses. Significance was based on a two-sided alpha level of 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS® software version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Demographic and Baseline Clinical Characteristics

Patient demographics and clinical characteristics were similar across all treatment groups and have been previously reported [23]. Briefly, the mean age of patients was 44.1 years, the majority were female (84.3%), and their mean duration of migraine was more than 20 years. The mean number of monthly migraine headache days was 8.6–9.0 across the treatment groups. Baseline PGI-S ratings (± Standard deviation (SD)) were similar across all treatment groups: 3.5 ± 1.1 (GMB 240 mg), 3.5 ± 1.2 (GMB 120 mg), and 3.6 ± 1.2 (PBO).

Severity and Symptom Improvement Outcomes

The primary efficacy result for treatment with GMB reported by Sakai et al. [23] was the mean change from baseline during the double-blind phase in monthly migraine headache days. The treatment difference for the reduction in monthly migraine headache days compared with PBO was 3.0 days for GMB 120 mg and 2.8 days for GMB 240 mg [23].

Treatment with GMB at a dose of 240 mg statistically significantly decreased the overall PGI-S rating (average over months 1–6) from baseline compared with PBO (Fig. 1; p = 0.013), indicating improved patient perceptions of their migraine severity. The change from baseline in PGI-S was statistically significantly greater with GMB 240 mg than PBO at month 4, and this difference was maintained through month 6 (Table 1). There was no statistically significant difference in the change from baseline in overall PGI-S between GMB 120 mg and PBO (Fig. 1) or at any time point (Table 1).

LS mean change from baseline in overall PGI-S rating (average of months 1–6). More negative scores indicate a greater improvement from baseline (score range 1–7). GMB galcanezumab, LS least squares, MMRM mixed-model repeated measures, PBO placebo, PGI-S Patient Global Impression of Severity. *p = 0.013 vs. PBO (MMRM analysis). The MMRM analysis included fixed categorical effects (treatment, month, the baseline number of monthly migraine headache days [< 8, ≥ 8], and treatment-by-month interaction) and continuous fixed covariates (baseline value and baseline-by-month interaction)

Treatment with GMB statistically significantly improved PGI-I (Fig. 2). The overall mean PGI-I score was statistically significantly lower for both GMB groups compared with the PBO group, indicating a greater improvement in migraine symptoms (Fig. 2a; p < 0.05). The effect of both doses of GMB on PGI-I score was observed at month 1 and was maintained through month 6 (Fig. 2b). The PGI-I response analysis indicated that for GMB 120 mg, a difference of 3.0 monthly migraine headache days corresponded to a 31% (95% CI 18.8–43.0) higher positive PGI-I response rate compared with PBO (Table 2). Similarly, for GMB 240 mg, a difference of 2.8 monthly migraine headache days corresponded to between 25% (95% CI 12.7–37.4) and 30% (95% CI 17.7–41.9) higher positive PGI-I response rates compared with PBO (Table 2). The differences in positive response rates between GMB and PBO in PGI-I were statistically significant.

Effect of GMB treatment on PGI-I score. Lower scores indicate greater improvement (score range 1–7). a Overall average (over months 1–6). b Monthly PGI-I score. GMB galcanezumab, LS least squares, MMRM mixed-model repeated measures, PBO placebo, PGI-I Patient Global Impression of Improvement, PGI-S Patient Global Impression of Severity, SE standard error. *p < 0.05 vs. PBO (MMRM analysis). The MMRM analysis included fixed categorical effects (treatment, month, the baseline number of monthly migraine headache days [< 8, ≥ 8], and treatment-by-month interaction), with PGI-S baseline value and PGI-S baseline-by-month interaction included as continuous fixed covariates

Patient distributions for PGI-I and PGI-S change from baseline at each month are summarized using frequency heatmaps in the electronic supplementary material, Fig. S1 (month 1)–Fig. S6 (month 6).There is an interesting trend in all months for all treatment groups. Almost all patients who had negative PGI-S change from baseline (i.e., an improvement in disease severity) showed improvement or no change (score 1, 2, 3, or 4) in PGI-I. However, the majority of patients who did not have a negative (0, 1, 2, 3, or 4) PGI-S change from baseline (no change or a worsening of disease severity) also showed improvement or no change (score 1, 2, 3, or 4) in PGI-I. This trend is most noticeable in patients who had no change from baseline in PGI-S.

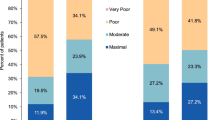

Patient Satisfaction with Medication

According to the PSMQ-M scores, patients treated with GMB were more satisfied with their medication and were more likely to prefer it to their previous medication compared with patients receiving PBO (Table 3). Higher proportions of patients receiving GMB gave positive responses for satisfaction and preference compared with patients receiving PBO. At month 6, patients who were receiving GMB treatment had statistically significantly higher positive response rates for satisfaction and preference compared with those receiving PBO (Table 4; p < 0.05). The majority of patients (ca. 51–62% at month 6) reported less and significantly less side effects relative to their previous medication for migraine across all three groups (Table 4), although a small percentage of patients receiving GMB (ca. 7–12% at month 6) experienced more side effects than with their previous medication (Table 3). Responses for side effects were statistically significantly positive only for GMB 240 mg compared with PBO (Table 4; p < 0.05).

Discussion

This is the first randomized controlled trial in Japanese patients with EM to show that patients have higher treatment satisfaction with GMB 120 mg and 240 mg compared with PBO. Improvements in patient-reported symptoms (measured by PGI-I) were observed as early as 1 month after initiation of GMB and were maintained through month 6.

According to the PSMQ-M, a majority of patients reported positive satisfaction and preference responses at month 1 and month 6. The results of this analysis provide important information on patient treatment satisfaction and may provide clinicians with a better understanding of patient perspectives regarding their preventive migraine treatment.

Patients’ impressions of their overall migraine disease severity (PGI-S) were slow to respond to treatment with GMB, with statistically significant differences vs. PBO observed only from month 4 onwards. This is unsurprising given the chronic nature of migraine and the severity of symptoms experienced by many patients during a migraine attack. In the present study, only GMB 240 mg had any effect on PGI-S ratings. Similarly, in the phase 3 REGAIN trial of GMB for patients with chronic migraine, a statistically significant improvement from baseline in the average PGI-S rating at month 3 was only reported in patients receiving GMB 240 mg [25]. By contrast, the phase 3 global EVOLVE-1 and EVOLVE-2 trials of GMB reported a statistically significant improvement from baseline in the average PGI-S rating over months 4–6 for both GMB 120 mg and 240 mg [7, 8]. To date, randomized controlled trials of monoclonal CGRP antibodies other than GMB have not included patients’ self-report of disease severity (or improvement) [30].

In the present study, similar positive responses to treatment with GMB in PGI-I and PGI-S were observed, although the effects of GMB on PGI-I were observed earlier in the study (month 1) and were maintained throughout the treatment period at both GMB doses. The frequency heatmap analyses may partially explain the discrepancy in the improvement observed between PGI-S and PGI-I, possibly resulting from a difference in signal detection levels between PGI-S and PGI-I. This discrepancy in signal detection levels may also explain why patients receiving GMB 120 mg did not show a statistically significant improvement over placebo in PGI-S, even though point estimates indicated GMB 120 mg was superior to placebo. At first glance the findings from this prespecified subanalysis might suggest that the preferred dosage of GMB might be 240 mg; however, it is important to note that in the clinical setting, the approved dosage of GMB is 120 mg. The suitability of this dose is borne out in this study by the clinically relevant benefit of this dose on both reduced monthly migraine headache days [23] and patient satisfaction measured using PSMQ-M.

As evidenced by the positive response analysis, reductions of 2.8–3.0 monthly migraine headache days corresponded to 25–31% higher positive PGI-I response rates in GMB-treated patients than in PBO-treated patients, suggesting that clinical improvements translate into patient-perceived improvements of their overall migraine disease. However, PGI-I response does not correspond solely to a reduction in monthly migraine headache days; for example, when the difference in monthly migraine headache days between GMB 120 mg and PBO was zero, 15% of patients receiving GMB 120 mg felt their migraine headache condition had improved (Table 2). This positive effect on patient improvement beyond the reduction in monthly migraine headache days may reflect reductions in side effects (as shown by the PSMQ-M results), reductions in migraine headache days that required acute medication use, reductions in total pain burden [15], or other areas of improvement. This improvement effect requires further investigation.

This is the first study to use patient-reported outcome measures to characterize patient satisfaction with GMB treatment in Japanese people with migraine. The results of the PSMQ-M indicate that, compared with patients receiving PBO, those receiving GMB were more satisfied with the medication and more likely to prefer it to their previous medication. This is clinically relevant because a previous study identified that the most common problems reported by Japanese patients with migraine for both acute and preventive therapies were a lack of efficacy of the medication and side effects [22]. Problems with preventive medication were experienced by more than 20% of Japanese adults who sought medical care for migraine [22]. The results of this study are therefore particularly pertinent to the experience of Japanese patients with migraine.

An intriguing aspect of this study is the potential role of patient satisfaction in treatment adherence. Patient adherence and persistence with treatment are known to be impacted by the efficacy of preventive medications [4], and dissatisfaction with preventive treatment may lead to discontinuation or a medication switch [12]. In the present study, patients receiving GMB reported global improvements in their condition and high levels of satisfaction with, and preference for, GMB as early as month 1. Mean treatment compliance for patients in all treatment groups was 100%, and the trial had a high continuation rate (95.9%) [23]. In combination with the reduction in average monthly migraine headache days within 1 month of GMB treatment [23], these early indicators of treatment satisfaction bode well for patient adherence with GMB treatment in a clinical setting.

The strengths of this study include its randomized, controlled, double-blind design. The 6-month duration allowed for measurement of changes in patient satisfaction over time. In addition, the study population of Japanese patients with migraine has been previously understudied, with respect to both treatment satisfaction and CGRP therapies generally.

The patient-reported outcomes detailed here were not the primary endpoints of the clinical trial and so were not considered in the statistical power and sample size calculations for the trial. Another limitation of the present study was that the 6-month duration may have been too short to observe substantial changes in patient assessments of disease severity. In addition, GMB was administered as a monotherapy. Although acute medications were allowed under certain circumstances, patient satisfaction outcomes for concurrent usage of GMB with other preventives are unknown.

Conclusions

This is the first study to demonstrate patient satisfaction with GMB at doses of 120 mg and 240 mg, and the relationship between treatment satisfaction and improvement in monthly migraine headache days in Japanese patients with EM.

References

Stovner LJ, Nichols E, Steiner TJ, et al. Global, regional, and national burden of migraine and tension-type headache, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17(11):954–76.

Lipton RB, Bigal ME, Kolodner K, Stewart WF, Liberman JN, Steiner TJ. The family impact of migraine: population-based studies in the USA and UK. Cephalalgia. 2003;23(6):429–40.

Lipton RB, Bigal ME, Diamond M, Freitag F, Reed ML, Stewart WF. Migraine prevalence, disease burden, and the need for preventive therapy. Neurology. 2007;68(5):343–9.

Blumenfeld AM, Bloudek LM, Becker WJ, et al. Patterns of use and reasons for discontinuation of prophylactic medications for episodic migraine and chronic migraine: results from the second international burden of migraine study (IBMS-II). Headache. 2013;53(4):644–55.

Agostoni EC, Barbanti P, Calabresi P, et al. Current and emerging evidence-based treatment options in chronic migraine: a narrative review. J Headache Pain. 2019;20(1):92.

Loder E, Rizzoli P. Pharmacologic prevention of migraine: a narrative review of the state of the art in 2018. Headache. 2018;58(Suppl 3):218–29.

Stauffer VL, Dodick DW, Zhang Q, Carter JN, Ailani J, Conley RR. Evaluation of galcanezumab for the prevention of episodic migraine: the EVOLVE-1 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol. 2018;75(9):1080–8.

Skljarevski V, Matharu M, Millen BA, Ossipov MH, Kim B-K, Yang JY. Efficacy and safety of galcanezumab for the prevention of episodic migraine: results of the EVOLVE-2 phase 3 randomized controlled clinical trial. Cephalalgia. 2018;38(8):1442–54.

Sacco S, Bendtsen L, Ashina M, et al. European headache federation guideline on the use of monoclonal antibodies acting on the calcitonin gene related peptide or its receptor for migraine prevention. J Headache Pain. 2019;20(1):6.

Dodick DW, Silberstein S, Saper J, et al. The impact of topiramate on health-related quality of life indicators in chronic migraine. Headache. 2007;47(10):1398–408.

Ayer DW, Skljarevski V, Ford JH, Nyhuis AW, Lipton RB, Aurora SK. Measures of functioning in patients with episodic migraine: findings from a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled phase 2b trial with galcanezumab. Headache. 2018;58(8):1225–35.

Ford JH, Ayer DW, Zhang Q, et al. Two randomized migraine studies of galcanezumab: effects on patient functioning and disability. Neurology. 2019;93(5):e508–17.

Shibata M, Nakamura T, Ozeki A, Ueda K, Nichols RM. Migraine-Specific Quality-of-Life Questionnaire (MSQ) version 2.1 score improvement in Japanese patients with episodic migraine by galcanezumab treatment: Japan phase 2 study. J Pain Res. 2020;13:3531–8.

Bigal ME, Serrano D, Reed M, Lipton RB. Chronic migraine in the population: burden, diagnosis, and satisfaction with treatment. Neurology. 2008;71(8):559–66.

Ailani J, Andrews JS, Rettiganti M, Nicholson RA. Impact of galcanezumab on total pain burden: findings from phase 3 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies in patients with episodic or chronic migraine (EVOLVE-1, EVOLVE-2, and REGAIN trials). J Headache Pain. 2020;21(1):123.

Silberstein SD, Stauffer VL, Day KA, Lipsius S, Wilson MC. Galcanezumab in episodic migraine: subgroup analyses of efficacy by high versus low frequency of migraine headaches in phase 3 studies (EVOLVE-1 and EVOLVE-2). J Headache Pain. 2019;20(1):75.

Stauffer VL, Turner I, Kemmer P, et al. Effect of age on pharmacokinetics, efficacy, and safety of galcanezumab treatment in adult patients with migraine: results from six phase 2 and phase 3 randomized clinical trials. J Headache Pain. 2020;21(1):79.

Ford JH, Foster SA, Stauffer VL, Ruff DD, Aurora SK, Versijpt J. Patient satisfaction, health care resource utilization, and acute headache medication use with galcanezumab: results from a 12-month open-label study in patients with migraine. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2018;12:2413–24.

Sakai F, Igarashi H. Prevalence of migraine in Japan: a nationwide survey. Cephalalgia. 1997;17(1):15–22.

Takeshima T, Ishizaki K, Fukuhara Y, et al. Population-based door-to-door survey of migraine in Japan: the Daisen study. Headache. 2004;44(1):8–19.

Takeshima T, Wan Q, Zhang Y, et al. Prevalence, burden, and clinical management of migraine in China, Japan, and South Korea: a comprehensive review of the literature. J Headache Pain. 2019;20(1):111.

Ueda K, Ye W, Lombard L, et al. Real-world treatment patterns and patient-reported outcomes in episodic and chronic migraine in Japan: analysis of data from the Adelphi migraine disease specific programme. J Headache Pain. 2019;20(1):68.

Sakai F, Ozeki A, Skljarevski V. Efficacy and safety of galcanezumab for prevention of migraine headache in Japanese patients with episodic migraine: a phase 2 randomized controlled clinical trial. Cephalalgia Rep. 2020;3:1–10.

Camporeale A, Kudrow D, Sides R, et al. A phase 3, long-term, open-label safety study of galcanezumab in patients with migraine. BMC Neurol. 2018;18(1):188.

Detke HC, Goadsby PJ, Wang S, Friedman DI, Selzler KJ, Aurora SK. Galcanezumab in chronic migraine: the randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled REGAIN study. Neurology. 2018;91(24):e2211–21.

Yalcin I, Bump RC. Validation of two global impression questionnaires for incontinence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189(1):98–101.

Hossack T, Woo H. Validation of a patient reported outcome questionnaire for assessing success of endoscopic prostatectomy. Prostate Int. 2014;2(4):182–7.

Kalali A. Patient satisfaction with, and acceptability of, atypical antipsychotics. Curr Med Res Opin. 1999;15(2):135–7.

Pharmaceutical and Medical Devices Agency (Japan). PMDA expert discussion report. 2013. https://www.pmda.go.jp/drugs/2013/P201300159/530471000_22600AMX00007_A100_2.pdf. Accessed 23 Jul 2020 (in Japanese).

Torres-Ferrus M, Alpuente A, Pozo-Rosich P. How much do calcitonin gene-related peptide monoclonal antibodies improve the quality of life in migraine? A patient’s perspective. Curr Opin Neurol. 2019;32(3):395–404.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all study participants, their families, the site investigators, and clinical staff. A patient review of the graphical PLS was provided by a member of the Envision the Patient panel. Project management support was provided by Aki Yoshikawa from Eli Lilly Japan K.K. Eli Lilly Japan K.K. was involved in the study design, data collection, data analysis, and preparation of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was sponsored by Eli Lilly and Company, manufacturer of galcanezumab. Publication costs, including the journal’s Rapid Service Fee, were funded by Eli Lilly Japan K.K. and Daiichi Sankyo Company, Limited.

Medical Writing and/or Editorial Assistance

Medical writing assistance was provided by Koa Webster, PhD, and Tania Dickson, PhD, CMPP, of ProScribe – Envision Pharma Group, and was funded by Eli Lilly Japan K.K. and Daiichi Sankyo Company, Limited. ProScribe’s services complied with international guidelines for Good Publication Practice (GPP3).

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published. All authors participated in the interpretation of the study results, and in the drafting, critical revision, and approval of the final version of the manuscript.

Authorship Contributions

Akichika Ozeki was involved in the study design and statistical analyses. Yoshihisa Tatsuoka and Takao Takeshima were investigators in the study and were involved in data collection.

Disclosures

Akichika Ozeki and Taka Matsumura are employees of Eli Lilly Japan K.K. Akichika Ozeki and Taka Matsumura own shares in Eli Lilly. Takao Takeshima has received speaker bureau fees regarding migraine for Pfizer Japan Inc., Eisai Co. Ltd., Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Kyowa Kirin Co. Ltd., Sawai Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Amgen Astellas BioPharma, Eli Lilly Japan K.K., and Daiichi Sankyo Company, Limited. Yoshihisa Tatsuoka has no conflicts of interest to declare. The patient reviewer of the graphical PLS received an honorarium, funded by Eli Lilly Japan K.K.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, the International Council for Harmonisation Guideline for Good Clinical Practice, and applicable laws and regulations. Ethical approval for the study, including the protocol and informed consent form, was obtained from the institutional review board (IRB) at each of the 40 study sites (see Table S1 in the electronic supplementary material for list of IRBs). All participants provided written informed consent.

Data Availability

Lilly provides access to all individual participant data collected during the trial, after anonymization, with the exception of pharmacokinetic or genetic data. Data are available to request 6 months after the indication studied has been approved in the USA and EU and after primary publication acceptance, whichever is later. No expiration date of data requests is currently set once data are made available. Access is provided after a proposal has been approved by an independent review committee identified for this purpose and after receipt of a signed data sharing agreement. Data and documents, including the study protocol, statistical analysis plan, clinical study report, blank or annotated case report forms, will be provided in a secure data sharing environment. For details on submitting a request, see the instructions provided at www.vivli.org.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tatsuoka, Y., Takeshima, T., Ozeki, A. et al. Treatment Satisfaction of Galcanezumab in Japanese Patients with Episodic Migraine: A Phase 2 Randomized Controlled Study. Neurol Ther 10, 265–278 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40120-021-00236-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40120-021-00236-5