Abstract

Metabolic and inflammatory pathways are highly interdependent, and both systems are dysregulated in Type 2 diabetes (T2D). T2D is associated with pre-activated inflammatory signaling networks, aberrant cytokine production and increased acute phase reactants which leads to a pro-inflammatory ‘feed forward loop’. Nutrient ‘excess’ conditions in T2D with hyperglycemia, elevated lipids and branched-chain amino acids significantly alter the functions of immune cells including neutrophils. Neutrophils are metabolically active cells and utilizes energy from glycolysis, stored glycogen and β-oxidation while depending on the pentose phosphate pathway for NADPH for performing effector functions such as chemotaxis, phagocytosis and forming extracellular traps. Metabolic changes in T2D result in constitutive activation and impeded acquisition of effector or regulatory activities of neutrophils and render T2D subjects for recurrent infections. Increased flux through the polyol and hexosamine pathways, elevated production of advanced glycation end products (AGEs), and activation of protein kinase C isoforms lead to (a) an enhancement in superoxide generation; (b) the stimulation of inflammatory pathways and subsequently to (c) abnormal host responses. Neutrophil dysfunction diminishes the effectiveness of wound healing, successful tissue regeneration and immune surveillance against offending pathogens. Hence, Metabolic reprogramming in neutrophils determines frequency, severity and duration of infections in T2D. The present review discusses the influence of the altered immuno-metabolic axis on neutrophil dysfunction along with challenges and therapeutic opportunities for clinical management of T2D-associated infections.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Nutrients and metabolites significantly regulate effector functions of innate immune cells in both steady state and during infections. Bidirectional crosstalk between the innate immune system and metabolic pathways form an immuno-metabolic axis that is intricately regulated. Accordingly, metabolic diseases such as obesity, type 2 diabetes (T2D) and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease are characterized by chronic low-grade inflammation with elevated pro-inflammatory mediators that alter innate immune functions and overt into a feed-forward loop leading to excessive inflammation [1]. Neutrophils are metabolically active and effector functions carried out by these cells are energy dependent [2]. Neutrophils constituting about 60–70% of white blood cells are the first non-local immune cells to respond to both inflammatory or infectious stimuli and thus making these cells as the first line of defense [3, 4]. During physiological conditions, neutrophils are generated through ‘steady state granulopoiesis’, where about 1011 neutrophils per day are released from bone marrow and this process is regulated by a master transcription factor CEBPα in association with chemokine axis, adhesion molecules and growth factors. Steady-state granulopoiesis shifts to ‘emergency mode’ during acute infections to increase neutrophil numbers which is driven by CEBPβ and associated with elevated levels of pro-inflammatory mediators including G-CSF [5]. Neutrophils are the short lived, fugitive, most abundant and terminally differentiated innate immune cells, eliminate infections through evolutionary conserved biological processes such as phagocytosis, degranulation, producing extracellular traps and regulating macrophages and B cell functions [3]. These processes rely upon glycolysis, stored glycogen, pentose phosphate pathway, TCA cycle intermediates and glutaminolysis for the source of energy [6].

Although neutrophils are attributed to their beneficial effects to eliminate infections, mounting evidences have shown that these cells display adverse effects associated with several diseases including T2D. Several labs including our own studies using pre-clinical and clinical models have demonstrated that hyperglycemia activates neutrophils constitutively and impedes their response to infections [7]. Hyperglycemia in T2D significantly reprograms neutrophil metabolism and reduces effector functions. As a consequence of elevated glucose concentrations in T2D, molecular shunting of glucose metabolism from glycolysis to polyol pathways is observed. In normoglycemic conditions, the glucose flux through the polyol pathway is limited due to low affinity and high Km (Michaelis constant) value of aldose reductase for glucose (50–100 mM) and hence, a major proportion of glucose is metabolized by hexokinase feeding into glycolysis [8, 9]. However, the excess glucose concentration triggers aldose reductase resulting in depleted Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) levels, a reducing equivalent and subsequently, accumulates osmotically active sorbitol [10,11,12]. Interestingly, several studies have demonstrated that the km value of aldose reductase for glucose varies among tissues such as 70 mM for the human placenta [13], 0.15 mM in rat lens, 0.11 mM for bovine lens and 651 mM for muscle tissue [13]. Aldose reductase activity was three times higher in diabetic individuals in erythrocytes and a significant correlation was observed between the enzyme activity and sorbitol levels [14]. Our metabolomics analysis in neutrophils isolated from T2D individuals also showed increased sorbitol levels [15]. These changes lead to reduced availability of NADPH for the normal functioning of neutrophils there by decreasing levels of the intracellular ROS scavengers, glutathione and modifies transcription factors activating pro-inflammatory genes (IL-6, TGF-α, TGF-β) [16].

Decreased scavenge and increased formation of cytokines activates naive neutrophils, causing a feed-forward loop of excessive inflammation in diabetes [17, 18]. Clinically, T2D subjects show increased pre-disposition to infections including sepsis, fungal infections, foot ulcers, bacterial pneumonia, urinary tract infections, blood stream infections, skin infections, soft tissue and eye infections. Interestingly, metabolic health of an individual determines the frequency, duration and severity of the infections. Nutrient ‘excess’ condition in T2D characterised by hyperglycemia, elevated lipids and branched-chain amino acids significantly alter immuno-metabolic axis, there by leading to constitutive activation, compromised mobilization and impeded acquisition of effector or regulatory activities of neutrophils and render these subjects for recurrent infections. In the present review, we catalogue and discuss how the altered immuno-metabolic axis in T2D influence neutrophil functioning during various infections. Further, we discuss challenges and opportunities to restore neutrophil function in T2D subjects for the clinical management of infections.

Neutrophils reprogram their metabolism to carry out effector functions

Neutrophils are metabolically active cells and rely on distinct metabolic pathways for their energy need. The neutrophils contain a modest number of mitochondria which makes them rely on other sources of the metabolic processes for their effector functions [2]. During differentiation, neutrophils utilize larger proportions of energy from glycolysis and FAO-mediated mitochondrial respiration and after being released into circulation, upon encountering harsh environment such as acute inflammation and infections, with the inaccessibility of glucose these cells adapt to glycogenolysis [19]. However, in hypoxic conditions, neutrophils shunt to glycolysis rather than mitochondrial respiration [20]. Neutrophils perform diverse immunological functions including ROS formation, phagocytosis, degranulation and extracellular trap formation to immobilize and eliminate pathogens. Even though glycolysis is the fundamental metabolic process, under glucose-depleted conditions, neutrophils depend on glycogenolysis for functions including phagocytosis [20]. Primed/activated neutrophils express increased levels of GLUT receptors on their surfaces associated with increased glucose uptake [13]. Rodríguez-Espinosa et al., demonstrated the metabolic requirement of NETs formation where, chromatin condensation was glucose independent and however, glucose was required for chromatin release during NETosis [21]. Primarily neutrophils depend on glycolysis as an energy source for NETs production. Neutrophils treated with a hexokinase inhibitor, 2-deoxyglucose (2-DG) reduced NETs formation in response to IL-6 and glucose [7].

Neutrophils are only myeloid cells that are competent in gluconeogenesis and glycogenesis, where these cells convert glucose-1-phosphate to glucose-6-phosphate, which is hydrolysed to glucose by glucose-6-phosphatases (G6Pase) which serves as a main source of ATP [22,23,24]. Robinson et al., showed an increased accumulation of glycogen in neutrophils that were isolated from inflammatory exudates in the peritoneal cavity of guinea pigs’ inflammation site compared to peripheral neutrophils [25]. In spite of limited oxygen and metabolic substrate, neutrophils survive and perform their functions in infected and injured tissue. A recent study showed that neutrophils undergo dynamic metabolic adaptation with a net increase in glycogen generation and storage by activating metabolic pathways gluconeogenesis and glycogenesis for their survival and effector functioning in infected sites. Further, authors demonstrated that neutrophils regulate glycogenesis and also utilize non-glucose substrates to generate glycogen stores by using radioactive flux and LC–MS tracing of U-13C glucose, glutamine, pyruvate and U-14C glucose in LPS treated or altitude-induced hypoxia in neutrophils [22].

An additional glucose-dependent metabolic pathway in neutrophils is the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP) also known as hexose monophosphate shunt which has been observed in both activated and resting neutrophils [26]. PPP is also involved in NETs formation induced by PMA and AF, which was demonstrated by blocking glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase of PPP by adding 6-aminonicotinamide (6-AN) [26]. For the synthesis of ROS, neutrophils switch to PPP to produce NADPH for superoxide generation which is catalysed by NADPH oxidase in phagosomes. Mutations in genes coding for subunits of the NADPH complex fail to produce ROS and leads to insufficient production of NETs which subsequently manifests into chronic granulomatous disease (CGD) [27]. As an alternative to PPP, mitochondrial glutaminolysis supports ROS formation by contributing to the formation of NADPH [6]. Chemotaxis is a pre-requisite for neutrophils to combat infections. The energy required for the migration of neutrophils towards the chemoattractant is provided by ATP generated from purinergic signaling from the mitochondrial TCA cycle and glycolysis [19]. Furthermore, neutrophils adopt/activate fatty acid metabolism during limited glucose availability. Mitochondrial FAO converts fatty acids to acyl-CoAs then it enters to TCA cycle as acetyl-CoA, and energy in form of ATP is generated through the electron transport chain (ETC).

Studies have demonstrated the significant role of glutaminolysis as a source of energy in neutrophils in performing their effector functions. Under glucose-depleted conditions cells including neutrophils, glutamate undergoes glutaminolysis and form α-ketoglutarate to enter the citric acid cycle and subsequently makes malate and further transform to pyruvate [28]. Using rat models, neutrophils displayed higher consumption and utilization of glutamine than glucose [29]. Glutamine has also been shown to play a significant role in the regulation of NADPH oxidase in rat neutrophils. Glutamine elevated the expression of gp91, p22 and p47 subunits of NADPH oxidase and generated increased super oxides [170]. Neutrophils from Wistar rat showed maximum uptake of glutamine when cultured in glutamine-rich media [28] and utilized energy for antimicrobial activity [30]. Furukawa et al., 1997 in post-operative subjects found decreased levels of glutamine and further showed that neutrophils from these subjects upon culturing with glutamine showed increased bactericidal activity [31]. Subsequently, the same group showed glutamine supplementation increased the ability of neutrophils from post-operative patients to perform efficient phagocytosis and produce elevated levels of reactive oxygen species [171]. Neutrophils display defective bacterial killing when gluconeogenesis and glutaminolysis are disrupted. Glutaminolysis plays a major role in glycogen synthesis in neutrophils. Glycogen levels were reduced in neutrophils stimulated with LPS in the presence of glutaminase/glutaminolysis inhibitor BPTES and MB05032 [22]. Taken together, these studies indicate glutamine plays an important role in regulating the effector functions of neutrophils.

Influence of hyperglycemia-induced inflammation on over-functioning of neutrophils

Precise neutrophil recruitment to infected tissue/organ is very important to combat microbes and to restore immune homeostasis during inflammation modulation and resolution, wound healing and tissue repair. Indeed, subjects with reduced absolute neutrophil counts are more prone to repeated infections while uncontrolled/abnormal neutrophil function may lead to tissue damage and associated autoimmune disorders [33]. Over the years, studies have demonstrated that in T2D, hyperglycemic milieu affects the normal functioning of neutrophils. Tian et al., in 2016, showed that exposure to advanced glycation products diminished neutrophil viability, accelerated cellular apoptosis, and hindered neutrophil migration [34. Neutrophils upon exposure to AGEs showed an increase in the production of inflammatory mediators and oxidative stress. However, no morphological changes were observed in neutrophils in T2D subjects [35]. Hyperglycemia impaired neutrophil mobilization and led to an enhanced metastatic spread in cancer [36]. Kuwabara et al., 2018 treated bronchoalveolar (BAL) tissue of Goto-Kakizaki (GK) and High Fat Diet (HFD) mouse with LPS and demonstrated an impaired in the chemotactic property of neutrophils, decrease in the neutrophil count, reduced release of IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α and MPO activity along with an increase in CXCL3 levels. These results revealed impaired response of neutrophils to LPS in HFD mouse [37]. Proteins such as Phospho-IKBα, phospho-NFκB and NFκB involved in the activation of TLR4 pathway in neutrophils were decreased in LPS-treated BAL of HFD-fed mice suggesting neutrophils from diabetic mouse were LPS insensitive [37]. In T2D, degradation of the extracellular matrix by proteases was overruled even in the presence of protease inhibitors indicating accelerated activity of proteases in T2D. Protease isoforms of membrane bound and intracellular cathepsin B and leukocyte elastase were significantly increased in T2D conditions [38]. Platelet activation plays an important role in process of atherogenesis and thrombosis in T2D-associated myocardial ischemia. Neutrophils in hyperglycemic conditions are triggered to produce S100 calcium-binding protein A8/A9 which binds to the receptors of Kupffer cells to enhance the production of thrombopoietin, which in turn interacts with c-MPL receptor on megakaryocytes and bone marrow progenitor cells to increase the proliferation resulting in reticulated thrombocytosis [39]. Umsa-ard et al., 2015 showed that hyperglycemia increased the expression of CD11b and CD66b in neutrophils which in turn induced the adherence of neutrophils to endothelial cells, may or at least in part involved in the development and progression of atherosclerosis in diabetic subjects [40]. Comparative transcriptome analysis of T2D and normal neutrophils deciphered significant differential expression of nearly 50 genes related to inflammation and lipid metabolizing genes including SLC9A4, NECTIN2, LILRB5, AKR1C1 and PLPP3 [41]. Methylglyoxal, a metabolite observed significantly higher in T2D subjects stimulated neutrophils to release cytokines such as IL-6, TNF-α and IL-8 rendering neutrophils to a pro-inflamed condition which may lead to reduced response to infections [42]. Bcl-2 is an anti-apoptotic protein and Bax is a pro-apoptotic protein. In T2D, significant apoptotic changes are seen where Bax expression is comparatively higher than Bcl-2 indicating increased apoptotic neutrophils [43]. Microarray analysis deciphered differential expression of miRNAs in neutrophils isolated from diabetic skin wound in comparison with non-diabetic derived neutrophils, particularly miR-129-2-3p. This miRNA regulates Ccr2 and Casp6 translation and is involved in inflammatory responses, phagocytosis, apoptosis, endocytosis, chemotaxis and endocytosis in neutrophils. The deregulation of miR-129-2-3p contributed to the dysfunction of diabetic-derived neutrophils [44].

Diabetic microenvironment impedes phagocytic ability in neutrophils

Phagocytosis is a central function of neutrophils to eradicate pathogens during infections and this key process is altered in T2D. The process of phagocytosis involves proteins such as cathepsin, defensin, lactoferrin and lysozyme to kill the pathogens [45]. Neutrophil apoptosis regulates effector functions, longevity, and free radical-mediated injury. Neutrophil-mediated phagocytosis is an effective immune function in Mycobacterium tuberculosis infections [46]. The major metabolic product of gut microbiota are short-chain fatty acids such as butyrate, propionate and formate. Increased levels of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) cause decreased neutrophilic mycobacterial phagocytosis along with decreased production of superoxide, hydrogen peroxide and hypochlorous acid. Due to altered levels of SCFAs, T2D confers a threefold increased risk for the development of tuberculosis [46]. T2D is the highly associated factor responsible for the complication of septic endophthalmitis and correlated to K. pneumoniae-induced liver abscess. Neutrophil-mediated phagocytosis of capsular serotypes K1/K2 of K. pneumoniae was lower in patients with T2D than normal healthy controls. Poor glycemic control in endophthalmitis and meningitis was associated with a decreased phagocytic rate of K. pneumoniae [47]. This defective killing of K1 and K2 strains was compensated by NETs-mediated killing [48]. Davidson et al., (1984) showed that phagocytic impairment in neutrophil was partially due to the reaction between the plasma protein and glucose concerned with opsonisation [49]. Staphylococcus aureus induced phagocytic activity was decreased in diabetic subjects in comparison with control after both the groups were treated with nicotinamide [50]. Mazade et al., 2001 demonstrated that in T2D, neutrophil-mediated phagocytosis of type 3 group B. Streptococcus was impaired. Authors showed that upon using alrestatin which is an inhibitor of the aldose reductase pathway, superoxides were generated for a significant increase in phagocytosis of GBS [51]. Adiponectin has been shown to reduce the production of ROS and also inhibited the process of phagocytosis. Adiponectin reduced the binding of E. coli bacteria to the surface of bacteria by reducing the complement receptor Mac-1 and further inhibited the phosphorylation of PKB and ERK1/2 to reduce the phagocytic process [52]. Neutrophil functions require ATP-as an energy source, which is produced mainly by the metabolism of glucose to lactate. As neutrophils from diabetic hosts display impaired glucose metabolism, the reduced energy of neutrophils in diabetic hosts may render them functionally refractory [53]. Taken together, T2D subjects are extensively prone to infections due to the defective phagocytic function and elucidating pathways to re-activate phagocytosis may be important to maintain homeostasis of the innate immune system.

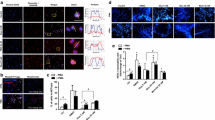

T2D neutrophils form constitutive NETs and renders to reduced response to infections

Upon activation, neutrophils expel their DNA and granular proteins to form a web like structure known as Neutrophil Extracellular Traps (NETs). Highly activated neutrophils produce NETs through which the pathogens are trapped and eliminated [45]. NETs consist of DNA to which histones and proteins released from granules are bound [54]. NETs immobilize the pathogens, preventing pathogens from spreading and also facilitates phagocytosis of the captured pathogen [4]. T2D is associated with increased levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-8 and which leads to the constitutive activation of NETs. Earlier studies from our lab have shown that hyperglycemic conditions in T2D induced constitutive NETosis and further neutrophils failed to form NETs in response to LPS [7]. Impaired or excessive NETosis play a role in promoting inflammation, thrombosis and endothelial dysfunction which contribute to diabetic complications [55]. It has been shown that elevated levels of homocysteine in T2D as a potent inducer of NETs. Mechanistically, NETs formed by homocysteine varied from other inducers by their requirement for calcium flux and mitochondrial superoxide [56]. PMA is a potent inducer of NETs, glucose ability to mimic PMA to induce NETs was related to its effect on PKC. Glucose also induced NADPH oxidase required by neutrophil for NETs formation [7, 55]. In T2D, neutrophils have a higher concentration of intracellular calcium and on the other hand, calcium flux is required for the formation of NETs. Increase in calcium flux elevated PAD4 levels which mediate histone citrullination [57]. It was observed that in T2D, neutrophils on treatment with IL-6, LPS and TNF-α did not form any extended NETs [7, 55, 58]. Miyoshi et al., demonstrated that serum MPO-DNA complexes associated with circulating NETs were significantly higher in T2D patients and suggested that elevated NETs formation in T2D patients may be a risk of microvascular complications. NETs formation is linked to both impaired wound healing and microvascular complications [59].

Degranulation is a process where neutrophils release their antimicrobial cytotoxic and other granular proteins from secretory vesicles. Azurophilic granules form first at different stages of neutrophil development, followed by specialised granules such as gelatinase granules, and finally secretory vesicles [60]. According to the formed-first-released-last hypothesis, these granules are easily mobilised upon an inflammatory stimulus at the plasma membrane in reverse order to their production [61]. Neutrophils produce a mixture of proteins from primary granules (azurophilic), secondary granules (specific) and tertiary granules, content of these granules has an antimicrobial function and help in eliminating infections. However, uncontrolled secretion of these mediators during the degranulation causes respiratory burst and leads to cell-mediated tissue damage [62]. Azurophilic granules constitute various peptides/protein including MPO, alpha-defensins, BPI, elastase, proteinase-3, and cathepsin G. Azurophilic granules constitute various peptides/protein includes alpha-defensins, MPO, elastase, cathepsin G, BPI, and proteinase-3. Small peptides such as alpha-defensins and cathelicidins play a role in the immune response by forming transmembrane pores that protect against a variety of fungi, bacteria, protists, and enveloped viruses. BPI neutralizes gram-negative bacteria by binding to the negatively charged LPS neutralizes the microbial activity [63]. Specific or secondary granules mainly constitute MMP, neutrophil collagenase-2, gelatinase-B, stromomelysin and leukolysin. Studies have shown that high glucose levels hinder neutrophil functions including degranulation. Hyperglycemia resulted in decreased E. coli endotoxin-induced neutrophil degranulation and an increase in coagulation [64]. Hyperglycemic conditions diminished inflammation-induced neutrophil degranulation and exacerbated procoagulant responses, whereas hyperinsulinemia inhibited fibrinolysis during the early inflammatory reaction due to extra stimulation of PAI-1 activity [65]. A Study showed reduced bacterial infections in diabetic mice with controlled blood glucose level [66]. Juan Huang et al., showed that high concentrations of plasma neutrophil elastase (NE) may also be considered as a marker of the development of complications, such as diabetic angiopathy and coronary artery disease [Full size image

Hence, inhibiting aldose reductase may facilitate in maintaining NADPH pools to utilize for forming NETs during infections. Earlier studies have elegantly demonstrated the kinetics aldose reductase reactions in lower and higher levels of its substrate glucose [128]. Under normal physiological conditions, about 3% of cytosolic glucose is processed via the polyol pathway, however, at higher concentrations of glucose, about 30% of the glucose enters the polyol pathway which makes it important in disposing of the glucose molecules and subsequent conversion to sorbitol [128]. Aldose reductase effectively catalyzes about 100 mM of D-glucose with a low Michaelis-Menton Constant, Km. This value is 20 times greater than the normal glycaemic level of 5 mM [129]. Accumulation of sorbitol results in elevated levels of reactive oxygen species, increased cellular damage and osmotic stress leading to diabetic complications [130]. Higher levels of ROS due to sorbitol may be one of the reasons for the constitutive production of NETs in hyperglycemic conditions [7].

Genetic variations in ALR2 gene have been demonstrated in predisposition to the onset and progression of diabetic complications. Independent studies have shown that ALR2 is activated by TNF-α [128, 129], synchrotron X-ray irradiation and oxidative stress during T2D leading to vascular damage [128]. Analysis of the transcription start site 2.1 kb upstream of the ALR2 gene was studied in the Chinese population residing in Hong Kong who are diagnosed with non-insulin-dependent diabetes. The study revealed 7 alleles of ALR2 of which (Z-2) was significantly associated with the early onset of retinopathy [131]. Abu-Hassan et al., performed a case–control study in the Jordanian population and revealed that C106T polymorphisms in the ALR2 gene were associated with diabetic retinopathy [130]. A case–control study among the natives of the Bali region in Indonesia showed that C(-104)T polymorphism in the ALR2 gene as a risk factor for diabetic retinopathy [132].

Targeting aldose reductase which drives the polyol pathway during diabetes could be a potential therapeutic strategy in the treatment and prevention of diabetic complications. A study by Varma et al. used quercitrin an isoflavone as aldose reductase inhibitors to prevent the accumulation of sorbitol formation in the cataract of diabetic patients [133]. Providing a Sorbinil-galactose diet proved to effectively abolish the polyol pathway of sugar metabolism, as evidenced by a progressive decrease in the lenticular dulcitol level and re-establishment of normal lens physiology in Sprague–Dawley rats [134]. Epalrestat (ONO-2235) and fidarestat (SNK-860) treatment were protective against diabetic nephropathy in clinical settings [135]. NADPH oxidase is required for glucose-formed NETs and its deficiency caused by aldose reductase’s competitive NADPH utilisation under high glucose conditions may be the cause of the impaired NET production. Ranirestat, a putative inhibitor of aldose reductase, also reduced cytosolic ROS and neutrophil elastase induced by high glucose. The formation of NETs was suppressed when neutrophils pre-treated with ranirestat under high glucose conditions. NADPH supplementation in neutrophil cultures in high glucose environments also markedly enhanced NET formation in response to LPS [15]. Additionally, two phase III clinical trials of the aldose reductase inhibitor ranirestat were completed successfully, and authors demonstrated its beneficial effects on diabetic neuropathy. The ranirestat therapy reduced the production of NETs by targeting aldose reductase activity and may serve as an effective method for preventing and treating cardiovascular problems in T2D [59]. Ranirestat treatment to streptozotocin (STZ)-diabetic rats and spontaneously diabetic Torii (SDT) rats showed inhibition of aldose reductase in both the sciatic nerve and lens [136, 137]. Another observational study by Ishibashi et al., demonstrated that comparatively to epalrestat, 500 nM ranirestat inhibited the effects of high glucose on elevated sorbitol levels, vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 mRNA levels in umbilical vein endothelial cells, and THP-1 cell adherence to human umbilical vein endothelial cells [138].

High glucose induces the formation of ROS and renders to increased oxidative stress. Using synthetic and natural anti-inflammatories may be another alternative to supress over functioning of neutrophils and NETs formation. A substantial drop in cysteinyl glycine, a crucial metabolic intermediate in the glutathione synthesis pathway, was observed in a metabolomic analysis of T2D neutrophils [15]. Glutathione supplementation effectively diminished glucose-induced neutrophil elastase and cytosolic ROS production and suppressed NETs formation in high glucose environment [15]. Inhibiting glucose-induced signalling changes and simultaneous activation of neutrophils to combat infections may be one of the potential approaches. The development of functional NETs may be aided by the combined autophagy and Nox2-dependent chromatin decondensation in intact neutrophils as well as the suppression of caspases. It has been shown that the PI3K/autophagy and NADPH oxidase inhibitors wortmannin and diphenylene iodinium (DPI), respectively, attenuated PMA-induced NETosis [139]. High glucose influences the phosphorylation of various upstream kinases, including AKT, ERK, and JNK (C-jun N terminal kinase). However, when neutrophils were precultured in high glucose and stimulated with LPS, these effects were abrogated. Newer insights into upstream kinases induced by glucose may aid in the development of therapeutic targets to block the effects of glucose and simultaneously restoring NETs in the presence of infections [140]. A metabolic regulator, itaconic acid (4-OI) blocked the Nrf2/HO-1/Hif-1-dependent pathways that lead to NET release. According to a study by Gabriela Burczyk et al., pre-treatment with 4-OI, a metabolic regulator, reduced the formation of NETs by increasing the expression/activation of Nrf2 and HO-1 and diminishing the expression of HIF-1, which was otherwise reduced and elevated by LPS, respectively, in mice's bone marrow-derived neutrophils [141]. It has been demonstrated that hyperglycemia reduces LPS-induced neutrophil degranulation, which in turn reduces the release of myeloperoxidase and elastase from azurophilic granules. This implies that neutrophil degranulation is abolished by elevated blood glucose levels in inflammatory situations [142, 143]. Accumulating evidence in T2D subjects, the reduced phagocytic activity of PMBCs is significantly reversible if glycaemic management is improved. The reduced phagocytic activity in T2D patients can mostly be attributed to blood glucose management. A study has demonstrated that the anti-inflammatory drug propofol, when combined with a lipid emulsion prevented the formation of NETs by suppressing PMA-induced ROS [144]. High glucose induces the release of neutrophil elastase during NETs formation. In rodent models, silvestat, a neutrophil elastase inhibitor delivered via nanoparticles, prevented NETs formation, reduced clinical signs of lung damage, and lowers serum levels of NE and other proinflammatory cytokines [145]. Yang Liu et al. (2018) illustrated that intravenous injection of CRISPR-Cas9 plasmids encoding gRNAs that target NE were encapsulated into the cationic lipid-assisted nanoparticles (CLANpCas9/gNE) successfully diminished expression of NE in epididymal white adipose (eWAT) and in the liver, whereby they successfully mitigated the insulin resistance of T2D [146]. Prostaglandin E2 is a critical regulator of inflammation, inhibited NETosis by activation of the cAMP–PKA pathway through the activation of its Gαs‐coupled receptors, EP2 and EP4 [147]. Consequently, restoring neutrophil functions may serve as a therapeutic strategy to manage infections in T2D.

Nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN) is an intermediate of NAD + biosynthesis, result of a reaction between a phosphate group and a nucleoside containing ribose and nicotinamide (NAM) [148]. Studies have shown that NAMPT-mediated NAD+ biosynthesis is severely conceded in metabolic organs such as liver and WAT of high-fat diet-fed mice (HFD). Strikingly, the administration of NMN a crucial NAD + intermediate and product of the NAMPT reaction improves glucose intolerance by restoring NAD+ levels in HFD-induced T2D mice. Further showed positive augments hepatic insulin sensitivity and activates SIRT1 which helps in restoring gene expression related to oxidative stress, inflammatory response, and circadian rhythm after NMN therapy [149]. A Randomized double-blind clinical trial of nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN) therapy on postmenopausal overweight/obese women with prediabetes showed positive effects on Insulin-stimulated glucose disposal, insulin signaling, and muscle insulin sensitivity [150]. Study on HFD mice by Jun Yoshino et al., stated that administration of the NMN to diet and age-induced T2D mice can be an effective intervention to treat the pathophysiology of T2D. Recent studies showed that Sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) one of the mediators of NMN can be used as a target in T2D which will be a promising therapeutic target since it actively participates in regulating insulin resistance, inflammation, glucose/lipid metabolism oxidative stress, and mitochondrial function. which is one of the mediators for these beneficial effects of NMN [149, 151]. Deacetylation of SIRT1 regulates NF-κB which plays a major role in hepatic insulin resistance [152, 153] and a report by Yoshino et al., 2011 showed increased level of acetylated p65, a component of NF-κB in HFD-fed mice evidenced that SIRT1 activity was suppressed by HFD. Long-term NMN administration may be a highly effective strategy to maintain improved SIRT1 activity in tissues and organs [149]. Other sirtuin family members (SIRT2-7) also contribute to the metabolic effects of NMN. Deficits in NAMPT-mediated NAD + production may specifically impair the functioning of mitochondrial sirtuins (SIRT3-5), which may contribute to the mitochondrial dysfunction seen among T2D [154]. It would be interesting to find influence of NMN therapy on neutrophil (dys)function in T2D.

T2D is a major health concern worldwide. According to IDF Diabetes Atlas 10th edition, it has been estimated that around 537 million people are suffering from diabetes globally, which will rise to 643 million (11.3%) by 2030 and to 783 million (12.2%) by 2045 with a huge mortality rate and more than 3.96 million people die worldwide every year due to T2D-associated complications including infections. Numerous theories have been put up to explain the relationship between diabetes and a higher risk of infections and many studies focusing on the possibly impaired neutrophil functions. However, mounting evidences confirm that glucotoxicity serve as a major cause for metabolic reprogramming of immune cells and render them incapable of effector functions. Collective data shows that metabolic routes like glycolysis, glutaminolysis and PPP are the major source of energy for the proper functioning of neutrophils which finds altered in diabetes individuals with infections. Therapeutic lowering of blood glucose may not be sufficient to manage T2D-associated infections due to the process of metabolic memory in different cell types. Shunting the metabolic pathways by treating with enzyme inhibitors may help in restoring NADPH pools to resensitize neutrophil functioning. Future studies are warranted to test these hypotheses in clinical models.