Abstract

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic is becoming a major hazard to public health worldwide. This is causing a significant impact on life and physical health, as well as on the psychological well-being of the general population. Since the emotional distress and the social restrictions caused by this epidemic, it must be expected that its impact will also extend to sexual health. The purpose of this study, the first including a large sample of the Spanish general population, was to analyze sexual behavior during the 99 days of confinement in Spain (INSIDE Project).

Method

One thousand four hundred forty-eight Spanish people, between 18 and 60 years old, were evaluated through an online survey during April 2020. The variables analyzed were the physical and social environment during confinement, sexual desire, type of sexual activity, masturbation, sexual intercourse, online sexual activity, general sexual frequency, sexual fantasies, degree of self-control over sexual drive, sexual abuse, general impact of confinement on sexuality, and emotional mood.

Results

Confinement has affected the sexual life of half of the Spanish population (47.7%), especially women. Those who reported a worsening of their sexual life are almost three times more (37.9%) than those who reported an improvement (14.4%).

Conclusions

Different factors have been significant predictors of the positive or negative evaluation about the impact of this confinement on sexual life, such as gender, couple life, privacy, stress level, and the perception of confinement as unbearable.

Policy Implications

These results have important implications for the public health and more especially sexual health of the Spanish population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Historical events partly determine the identity of a society and affect the development of the life span of people, together with other biological, environmental, and personal factors (Baltes, 1985). As ocurred with other relevant events, such as the emergence of the Internet in the 1980–1990s (Griffin-Shelley, 2003), in 2020, an agent of a viral nature is writing a new chapter in the history of humanity and, possibly, lead the path for a new way of living and expressing sexuality.

The disease caused by novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 was declared as a Public Health Emergency of International Concern on January 30, 2020, by the International Health Regulations Emergency Committee. After that, this was recognized as a global pandemic on March 11, 2020, by the World Health Organization (WHO) (Instituto de Salud Carlos III, 2020a). According to official sources, on September 27, 2020, COVID-19 has been confirmed in more than 32.7 million people worldwide, around 17% are in the European region (WHO, 2020). On October 2, 2020, Spain (789,932) is the second country with most confirmed cases in the European Union, behind Russia (1,185,231), followed by France (577,505), UK (460,178), Turkey (318,663), and Italy (317,409). Moreover, Spain is the third country with the highest number of deceased people (32,086). More than 150,000 people in this country have needed hospitalization or admission to intensive care units (Ministerio de Sanidad, 2020). This global health emergency has been the greatest challenge that the Spanish health system has faced (Legido-Quigley et al., 2020). As a consequence, more than 40,000 health professionals had been infected on May 10, 2020. This data represents 15.7% of the total reported cases (Instituto de Salud Carlos III, 2020b).

Given the known particular properties of this virus and the absence of a tested treatment and vaccine, prevention is crucial to reverse the pandemic (Sohrabi et al., 2020). In this context, all countries have been forced to take drastic measures based on reducing movement to disminish its spread (Dowd et al., 2020). In Spain, specifically, the Council of Ministers decreed the “State of Alarm” for the entire national territory on March 13, 2020, with an initial duration of 2 weeks that lasted until June 21, 2020. Spanish society has lived for months with strict rules on hygiene, social distancing, suspension of all non-essential activities, and confinement of a large part of the population (Real Decreto 463/2020). After that, the deescalation process for the transition to the “new normality” began with important prevention and containment measures such as the mandatory use of masks (Real Decreto-Ley 21/2020). At the moment, the new wave of infections still continues to progress in this country and causes great suffering, especially among the most vulnerable groups (Ballester-Arnal & Gil-Llario, 2020).

This unprecedented historical moment could influence on different generations (Mira, 2020) and their system of beliefs and values (Li et al., 2020a). At the same time, this is also having significant negative psychological effects on the general population as numerous studies have shown, mainly in eastern countries such as China (Huang & Zhao, 2020; Qiu et al., 2015; Lichtenberg, 2014), and psychological adverse conditions (Badger, 2017; McCann et al., 2019; Rokach, 2019; Weiss et al., 2019) affect sexual functioning and sexual satisfaction, becoming worse the quality of individual and dyadic sexual life. In addition, these also influence on the engagement in risky sexual behaviors. However, there is a lack of studies focused on how a virus, whose transmission routes include body fluids that may be present in everyday gestures such as sweat, tears, or saliva, can affect sexual behavior. Tenkorang (2018) evaluated safe sexual behaviors in a group of Ghanaian men and women in the context of the Ebola virus. Nevertheless, the risk of COVID-19 virus goes much further and, unlike the Ebola virus, it is transmitted through the air and spread by casual contact. Probably, this is the first time that these current generations are living a scenario when social standards, affection, privacy, and sexual rights are at risk. Nevertheless, there are still few studies examining how this pandemic is affecting the sexual life of society and some of them include important methodological deficiencies. Specifically, only two studies with large samples of general population have been only found, one focused on the USA, Canada, the UK, and Australia (Lehmiller et al., 2020), and another on Great Britain (Jacob et al., 2020). A third one also included an important number of participants from the USA although this was restricted to men who have sex with men (MSM) (Sanchez et al., 2020). The remaining of the published studies have only evaluated between 58 and 459 participants belonging to the general population from Bangladesh, India, and Nepal (Arafat et al., 2020), Japan (Taniguchi et al., 2020), and a very small group of women from Italy (Schiavi et al., 2020) and Turkey (Yuksel & Ozgor, 2020). The only study found that has explored the impact of COVID-19 on the Spanish population is the review by Ibarra et al. (2020). This presents preliminary data from 279 participants who responded to an English and Spanish version survey. However, the authors do not provide the characterization of the sample or the methodology used, so we cannot say that the methodological standards are met.

In general, there are diverse results depending on the country of the participants and the variables analyzed. Regarding sexual frequency with respect to the period before confinement, a decrease exists as in the study by Lehmiller et al. (2020) but also an increase as in the study by Yuksel and Ozgor (2020); thus, the results are inconclusive. Other studies, in line with Lehmiller et al. (2020) or Sanchez et al. (2020), indicate that the sexual repertoire has expanded with new activities such as sexting or viewing pornography, the use of recreational drugs, and alcohol consumption. In addition, the use of dating apps would have decreased or the motivation to use them would have changed. Finally, studies by Taniguchi et al. (2020), Yuksel and Ozgor (2020), and Schiavi et al. (2020) have observed a deterioration of sexual function, sexual satisfaction, and quality of life.

Since the response to this pandemic also requires attention to sexual health as a fundamental pillar of physical and mental well-being, the aim of this study is to analyze, in a comprehensive manner, the sexual habits of the Spanish general population during the COVID-19 confinement (INSIDE Project). This study is carried out from the cognitive-behavioral perspectives of human sexuality, which defend that the social and physical environment has a very important influence on our sexual behavior. Therefore, such a specific situation like confinement could change our sexual behavior. In addition, they also incorporate a cognitive vision, in which it understands that not all people have the same reaction to certain events and that there may be important individual differences depending on how that situation is interpreted. For this reason, this study evaluates the physical and social environment, specific sexual behaviors, the perception of the impact of confinement, and also how variables such as emotional state have been able to influence a greater or lesser impact on sexuality. Moreover, gender perspective has been included because it is a relevant factor of the experience of sexuality, as shown by different reviews (Petersen & Hyde, 2010) and articles in which gender differences are shown in different sexual behaviors or aspects, such as, for example, in the experience of the first sexual relationship (Reissing et al., 2012), in performing online sexual activities (Shaughnessy et al., 2011), in sexting (Baumgartner et al., 2014), in the use and acceptance of pornography (Willoughby et al., 2014), in sexual infidelities (Gil-Llario et al., 2017), in masturbation (Driemeyer et al., 2017), or in the use of sex toys (Davis & Hines, 2020).

Method

Participants

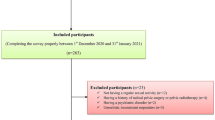

By means of a convenience sampling, 1632 completed answers were obtained (2562 were partial answers). Among all of them, we selected 1478 people who meet the inclusion criteria: being over 18 years old (n = 1623) and living in Spain (n = 1478). Furthermore, eight non-binary transgender people (they did not identify as either male or female) were eliminated, since the low number of people did not allow statistical analyses. In the same way, it was observed that from 60 years of age, there was a great dispersion of age, so we proceeded to eliminate those people older than 60 years (n = 22), since their inclusion could bias the results.

Finally, the sample consisted of 1448 Spanish people aged between 18 and 60 years old, including 67.5% women and 32.5% men. The average age was 31.92 years old (SD = 10.1). In relation to sexual orientation, 78.3% self-identified as heterosexual, 9.9% as bisexual, 8.7% as homosexual, 2.5% as pansexual, 0.2% as asexual, and 0.3% self-identified with “other sexual orientations.” Regarding the romantic relationship status, 43.8% had regular partner, 31.6% were single people, 20.6% were married or with de facto partner, 3.6% were separated or divorced, and 0.4% were widow/widower.

Measures

An ad hoc questionnaire with 59 items, created by the Qualtrics platform, was used. This mainly evaluates different sexual behaviors developed during the COVID-19 confinement, through a subjective and sometimes retrospective report of the participants. For this research, only a total of 42 items based on a varied format were included. The evaluated topics were the following:

Physical and social environment in which the confinement has ocurred. It is evaluated whether people had been alone or in company during this confinement, and in this last case, number of people and if they were people with whom they usually cohabitate. Other question evaluated if there was a possibility of privacy at home, with safe areas where they could have sexual activity without being disturbed.

Sexual desire. The intensity of sexual drive or desire during confinement was evaluated by a Likert-type item with seven response options. The answers ranged from “Much less intense than before” to “Much more intense than before.”

Type of sexual activity. A multiple choice item evaluated the type of sexual behaviors that people carried out during this confinement. There were different options: “I have masturbated,” “I have masturbated using sex toys,” “I have had sex with my partner,” “I have had sex with my boy roommate,” “I have had sex with my girl roommate,” “I have skipped the quarantine to have sex with someone I was not living with,” “I have had online sexual activity (viewing pornography, chats, webcam, sharing photos/videos of my own with sexual content, etc.),” and “Others.”

Masturbation. In case they reported having masturbated, using or not sex toys, there were four more items. First, two items explored the frequency of masturbation before and during confinement. The ordinal scale, of seven response options, ranged from “More than once a day” to “Never.” Furthermore, they were asked about the time invested on each masturbation during confinement. The response scale, of seven ordinal options, ranged from “Much less time than before” to “Much longer time than before.” Finally, they were asked how satisfactory these masturbations were during confinement by a scale of seven ordinal responses ranging from “Much less satisfactory than before” to “Much more satisfactory than before.” In addition, if they reported using sex toys for masturbation, one question explored if they had already carried out this behavior before confinement by a Yes or No response.

Sexual relationships. If they had practiced sex with their partner, their roommate, or if they had skipped confinement to have sex, how often they had sex before and during this confinement was explored through a ordinal scale of seven response options. The response scale ranged from “More than once a day” to “Never.” Second, they were asked about the time invested on each sexual relationship during confinement. The scale, of seven response options, ranged from “Much less time than before” to “Much longer than before.” Finally, they were asked how satisfactory these sexual relations were during confinement by a seven response options scale ranging from “Much less satisfactory than before” to “Much more satisfactory than before.”

Online sexual activity. If they reported online sexual activities during confinement, they were evaluated by three more items. A Likert-type item explored how much time they had invested on each online sexual activity during confinement by a seven-point scale that ranged from “Much less time than before” to “Much more time than before.” In addition, two other items evaluated how many minutes they dedicated to each sexual activity before and during confinement.

General sexual frequency. A Likert-type item evaluated the general frequency of sexual behaviors during confinement, compared to their previous situation, by a scale of seven response options ranging from “Much less frequently than before” to “Much more frequently than before.”

Whether they reported less frequency, they were evaluated with two more multiple-choice items. On the one hand, they were asked what factors they considered had caused this decrease in sexual activity, with the following answer options: “Lack of intimacy,” “Lack of sexual desire,” “Stress,” “Worries,” “Not being able to be with my partner,” “To overload by being with my partner a long time,” “Conflicts with my partner,” “Impossibility to leave home,” and “Other.” On the other hand, the possible consequences that they had experienced due to the decrease in this sexual frequency were evaluated, they could choose between: “Irritability,” “Conflicts,” “Psychological discomfort,” “More sexual fantasies,” “Sexual fantasies I did not have before,” “Sexual behaviors I did not have performed before,” “Thoughts of having sexual relationships with a family member,” or “Other.”

However, if they answered with any of the options that indicated a higher sexual frequency, two other questions were asked. On the one hand, they were asked what factors they considered had caused this increase in sexual activity, with the following response options: “For boredom, to distract me,” “To reduce my anxiety,” “To relax me,” “To make me happy,” “For a sexual drive increase,” “For investing more time with my partner,” “Because I am alone, and nobody controls me,” “Because people are more available to cybersex,” “Because I feel curiosity of being on lockdown,” and “Other.” On the other hand, the possible consequences that they had experienced due to the increase in this sexual frequency were evaluated, they could choose between: “A better mood,” “More relaxation,” “Regrets or guilt,” “Conflicts with my partner,” “Being unfaithful to my partner,” “Lower satisfaction of sexual behaviors,” or “Other.”

Sexual fantasies. It has been observed that people look for ways to satisfy the sexual desire, for example to have same-sex behaviors, in confinement or isolation situations such as in prisons. This occurs in both men (Richters et al., 2012) and women (Einat & Chen, 2012). For this reason, we evaluate possible behaviors that could have occurred with the intention of satisfying sexual desire during this confinement by COVID-19. In particular, three items evaluated the existence of a series of sexual fantasies during confinement. First, when they had a stable partner, were married or with de facto partner, they were asked if they had fantasized about being unfaithful to their partner during confinement. When they self-identified as heterosexual people, they were asked if they had fantasized about having same-sex intercourse during confinement. Finally, when they self-identified as homosexual, it was evaluated whether they had fantasized about having sex with someone of another sex during confinement.

Degree of control over sexual urges. Two items explored what degree of perceived control they had over their sexual activity before and during confinement. By means of a scale of four alternatives, the response options were as follows: “Nothing,” “Something,” “Enough,” or “A lot.”

Sexual abuse during confinement. Two items assessed whether they had been forced by another person to have sex during confinement or whether they had forced another person to have sex with them.

Global evaluation of the confinement impact. One item explored the global impact of confinement on their sexual life by one of these three options: “It has improved my sexual life,” “It has not altered my sexual life,” or “It has made worse my sexual life.” After that, they were asked about what specific aspects had improved or worsened, with non-exclusive alternatives of dichotomous response.

If they answered that their sexual life had improved, through a multiple-choice question, they were asked in what aspects they had done it, being able to choose between: “I have more frequency of sexual activity,” “I have not had pressure to have sex (because my partner was not or was not privacy),” “I have broadened the type of sexual practices in couples,” “I have explored myself more by masturbating,” “I have invested more time on fantasizing,” “I have explored other sexual orientations,” “I have had sex with a person I would never have done with before,” or “Other.”

On the other hand, if they answered that their life worsened, they were asked in what aspects, through a multiple-choice question. The response options were: “The frequency of sexual activity has decreased,” “The frequency of sexual activity has increased,” “I have received pressure by other people to have sex,” “I have not privacy to have sexual relationships,” “I have not privacy to masturbate calmly,” “I have had sexual fantasies that have made me feel bad,” “I have been sexually attracted to a new person and I have felt discomfort,” “I have had same-sex intercourse and I have felt discomfort” (option shown only to heterosexual people), “I have had sex with someone of the other sex and I felt discomfort” (option shown only to homosexual people), “I have been unfaithful to my regular partner,” or “Other.”

Mood. Five Likert-type items evaluated the mean level, during confinement, of anxiety, depressive mood, boredom, stress, and to what extent they had considered that the confinement situation was becoming unbearable. The response options were “Not at all,” “Somewhat,” “Mostly,” and “A lot.”

Procedure

On March 16, 2020, the Spanish Government decreed the State of Alarm due to the health emergency caused by coronavirus, forcing the confinement of the Spanish population until May 2, when the outings were allowed to do sport or to walk in different time bands according to age range. Finally, on June 21, the state of alarm ended.

A descriptive research was desinged and responses were collected through convenience sampling. Since April 3 and during strict confinement, until May 2, an advertisement was disseminated on the Internet on social networks (Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Whatsapp, and Telegram) requesting participation in a study to assess sexual behavior during the COVID-19 confinement.

When participants clicked on the advertisement, before answering the online questionnaire, they reach a screen where they were informed about the anonymous, voluntary, and confidential nature of the research. Moreover, they were asked for their informed consent. The research had the permission of the Deontological Commission of the Universitat Jaume I (Castellón, Spain). Additionally, the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki were followed at all times.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed by the SPSS statistical package (version 25.0). Percentages were calculated for categorical variables for both the total sample and each gender separately. Differences according to gender were analyzed by the chi-square test and the Cramer’s V was used to calculate the effect size. The Wilcoxon test was used to evaluate those percentages that had been compared in related samples (before and after confinement).

Finally, to predict the variables that affect the improvement or the deterioration of the sexual life during the COVID-19 lockdown, a multinomial logistic regression was carried out. The dependent variable was the impact on sexual life, that is, if had improved, had deteriorated, or had not change at all. Among the independent variables were gender, age, sexual orientation, living with a partner during confinement, privacy at home, living alone during the lockdown, how hard the lockdown has been and levels of stress, anxiety, depression, and boredom during that time.

Results

Physical and Social Environment in Which Confinement Has Occurred

As Table 1 shows, most of the people evaluated were in company the months of confinement (88.5%) compared to 11.5% who were alone. The last percentage is significantly higher among men (15.1%) than among women (9.7%) (χ2 = 8.964, p = 0.003). The people with whom they lived were mainly the couple (50.2%), followed by the father/mother (40.9%), the siblings (23.3%), and the children (22.5%). Men have been more accompanied by parents and siblings than women, who have been more accompanied by their partners. There are statistically significant differences in these variables. In many cases (86.4%), those people with whom they were confined were the same with whom they used to live. There are also significant differences in which men (89.3%) exceed women (85.1%) (χ2 = 3.949, p = 0.047). For all these results, the effect size has been small (see Table 1). Finally, 79.4% of the total sample, without differences between men and women, reported that, in the location where they were confined, there were places where they could have a certain privacy.

Sexual Desire

Regarding sexual desire, the total sample is divided into three quite similar subgroups. Approximately one third, 35.9% stated that they had a higher sexual desire during confinement, 34.9% had a lower desire and 29.1% nearly the same (see Table 2). However, there are significant differences according to gender (χ2 = 15.844, p = 0.015, V = 0.105). In particular, women revealed a higher percentage of those who had more desire than usual (37.8%) than men done (29.1%), but the opposite ocurred with those who felt less sexual desire (39.5% in men and 34.3% in women). That is, in general terms, men decreased desire while women increased it.

Types of Sexual Activity

In general, in the total sample, the most performed sexual practices were in order, traditional masturbation (without using sex toys) (61%), followed by sexual relationships with the partner (40%), online sexual activities (28.4%), and masturbation using sex toys (20.2%), highlighting that 4.1% skipped confinement to have sexual relationships with another person (see Table 2). Except for the last behavior, there are statistically significant differences according to gender. Men report higher percentages for traditional masturbation (χ2 = 105.895, p < 0.001, V = 0.270), and online sexual activity (χ2 = 83.198, p < 0.001, V = 0.240), both with a moderate effect size; and women for masturbation using sex toys (χ2 = 36.562, p < 0.001, V = 0.159), and intercourses with partners (χ2 = 25.774, p < 0.001, V = 0.133) (see Table 2).

For each of these practices, we explored if there had been any changes from the pre-confinement situation. Regarding masturbation, the most usual frequency before confinement for men was 4–7 times per week (44.4%), followed by 2–3 times per week (29%) and more than once a day (12.5%) (see Table 3). However, during confinement, the percentage of those who did it more than once a day rose to 25.8%. The changes were significant when applying the Wilcoxon test (p = 0.001). The changes were also significant for women (p < 0.001). Thus, before confinement, the most prevalent frequencies were 2–3 times per week (33.8%), followed by 1 time per week (19.4%), 2–3 times per month (18%), and 4–7 times per week (17.8%). Only 2.5% did it more than once a day. However, during confinement, this last percentage increased to 8.1% and the previous one to 20.5%. Regarding the invested time on masturbation (see Table 2), half of those evaluated, 49.6%, invested the same time as before, while for the other half, confinement had an impact on the amount of time dedicated to masturbation. However, similar as sexual desire results, this was in two different directions: 27.2% invested more time and 23.1% less time. Regarding the satisfaction obtained by masturbating, something similar occurs. Slightly more than half (57.3%) perceived it as satisfactory as before, while almost the other half is divided between those who stated that it was less satisfactory (26.4%) and those who indicated that it was more satisfactory (16.3%). For neither of these two variables, there were statistically significant differences according to gender (see Table 2).

The use of sex toys in masturbation slightly varied due to the situation of confinement. Most of people who used them (98.3%) had already done before confinement, with no differences between men and women. This also occurred for most of those who had sexual relationships with their partner or roommate (see Table 2).

Regarding sexual relations, the most common frequency for men before confinement was 2–3 times per week (45.6%) followed by once a week (19%), 4–7 times per week (15.2%), and 2–3 times per month (13.9%) (see Table 3). During confinement, the percentages were respectively 38%, 14.6%, 20.3%, and 17.7%, not revealing significant differences by the Wilcoxon test (p = 0.788). Nor was it for women (p = 0.702) for whom the most common frequency before confinement was 2–3 times per week (41.5%) followed by once a week (26%), 2–3 times per month (14.9%) and 4–7 times per week (11.6%). After that, these percentages were respectively 31.4%, 22.1%, 17.9% and 16.6%. About the invested time on sexual relationships (see Table 2), half of those evaluated (52.3%) maintained it and in the other half, 20.5% invested less time and 27.1% invested more time. Just over half (59.1%), these were equally satisfactory, while for 20.1%, they were less satisfactory and an almost identical 20.8% stated that these were more satisfactory. These two variables did not obtain satistically significant differences according to gender (see Table 2).

Finally, regarding online sexual activities (see Table 2), the percentage of those who maintained the invested time on them was lower (34.1%). Among those who were affected by confinement (65.9%), only 19.3% stated spending less time on these activities compared to 46.7% who admitted spending more to them. Once again, there were not statistically significant gender differences. Adittionally, those who did it, reported investing significantly more time on each online sexual activity. Among men, the mean before confinement was 23.8 min (SD = 27.9) and during it was 35.2 min (SD = 36.4) (t = 5.04, p < 0.001). Among women, the mean increased from 18.8 min (SD = 23.4) to 30.8 min (SD = 43.1) during it (t = 3.50, p = 0.001).

Global Frequency of General Sexual Activity, Reasons, and Consequences of Changing

The frequency of general sexual activity has maintained in 26.6% of participants and has been affected in most of them, almost equally in the two opposite directions. In particular, it has been lower for 38% and higher for 35.5%. This variable has obtained significant differences according to gender (χ2 = 26.025, p < 0.001, V = 0.134). In men, 30.1% have maintained the same frequency, while the percentage of women has been lower (24.9%). Contrarily, more women (41.3%) than men (31%) have had less frequency. Moreover, more men (39.8%) than women (33.8%) have had a higher frequency (see Table 4).

The main reasons for the lower sexual frequency have been in order: worries (41.5%), stress (37.5%), lack of desire (35.3%), lack of privacy (27.3%), not being able to be with the partner (26.4%), or being locked up at home (24.8%). In any case, 7.8% reported overloading by being with the partner a long time or having conflicts with them (7.7%) and these are also interesting. None of these reasons revealed significant differences according to gender, except for the stress (χ2 = 4.628, p = 0.031, V = 0.092) and lack of sexual desire (χ2 = 4.581, p = 0.032 V = 0.091) in which the percentages of women are higher. Only for the lack of privacy and being locked up at home, the percentages of men have exceeded those of women, although not significantly.

Moreover, the main consequences of the lower sexual frequency have been in order: none (42.1%), irritability (24.6%), psychological discomfort (22.4%), having more sexual fantasies (17.3%), and couple conflicts (11.5%). Additionally, other consequences have highlighted such as having fantasies that they had never had (5.5%), engaging in sexual behavior that they had not performed before (1.5%) or even having thoughts of having sexual relationships with a family member (0.7%). Irritability is the only one that reveals statistically significant differences by gender (χ2 = 8.376, p = 0.004, V = 0.124), being more present in women. Men only exceed women in a non-significant term for having new sexual fantasies and thoughts of having sexual relationships with a family member (see Table 4).

Regarding the reasons for the higher frequency, the main ones are the following: increase of desire (48.6%), seeking to relax (45.7%), distracting oneself from boredom (39.9%), investing more time on partner (29.2%), or reduce anxiety (29%). In the distance, are reported more available people to cybersex (6.6%), being alone and perceiving that nobody controls them (6%) and curiosity about feeling trapped (1.9%). There were only significant gender differences, in favor of men, in searching for distraction (χ2 = 17.151, p < 0.001, V = 0.183) and more available people to cybersex (χ2 = 4.774, p = 0.029, V = 0.096). Moreover, women exceed men in increasing sexual drive (χ2 = 4.898, p = 0.027, V = 0.098) and investing more time on partner, showing a moderate effect size (χ2 = 22.492, p < 0.001, V = 0.209).

Finally, the consequences of this higher frequency have been in order feeling more relaxed (44.7%) and having a better mood (41.2%), although for 30.2%, there have been none. Others showed a lower percentage such as less sexual satisfaction (6%), remorse or guilt (2.9%), being unfaithful (1.2%), and conflicts with the partner (1%). In most of these consequences, there are significant differences according to gender. Men exceed women in the appreciation of no consequence (χ2 = 14.263, p < 0.001, V = 0.167), lower sexual satisfaction (χ2 = 5.324, p = 0.021, V = 0.102), and remorse or guilt (χ2 = 4.068, p = 0.044, V = 0.089). However, women exceed men in more relaxation (χ2 = 4.068, p = 0.044, V = 0.089) and better mood, with a moderate effect size (χ2 = 26.440, p < 0.001, V = 0.227) (see Table 4).

Sexual Fantasies

During confinement, 27.4% of the general sample stated that they had the fantasy of being unfaithful to their stable partner, being significantly higher in men (35.2%) than in women (24.5%) (χ2 = 10.538, p = 0.001, V = 0.107). If there had been fantasies opposed to self-assigned sexual orientation was also evaluated. Once again, there were also significant differences according to gender. Among those who self-identified as heterosexual people, 13.8% had homoerotic fantasies, although the percentage in men (7%) is half of the women’s percentge (16.5%) (χ2 = 17.084, p < 0.001, V = 0.124). Moreover, 12.8% of those who self-identified as homosexual people stated that they had heteroerotic fantasies; the percentage among men is three times lower (9.1%) than for women (26.9%) (χ2 = 5.867, p = 0.015, V = 0.217).

Degree of Control Over Sexual Activity

The perceived degree of control over sexual activity decreased significantly during confinement in both men and women (Wilcoxon’s p < 0.001). Thus, those men who reported to have “nothing, some, enough, or much control” before confinement were respectively 3.6%, 19.7%, 58.8%, and 17.8%, compared to 8.9%, 29.1%, 43.1%, and 18.9% during confinement. Among women, the percentages were respectively 3.3%, 16%, 51.3%, and 29.5% before confinement compared to 7.9%, 23.1%, 42%, and 27% during this.

Sexual Abuse During Confinement

Among participants, 2.8% reported having felt sexually forced by another person during confinement. The percentage was higher among men (3.3%) than among women (2.6%), but the differences were far from significance (χ2 = 0.459, p = 0.498, V = 0.019). On the contrary, 1.1% acknowledged having forced another person, and despite the fact that the percentage was higher in men (1.7%) than in women (0.8%), once again the differences were not significant (χ2 = 2.430, p = 0.119, V = 0.043).

Global Evaluation About the Confinement Impact

In line with the heterogeneity of aspects mentioned, the global evaluation about the confinement impact on sexual life was explored (see Table 5). For approximately half of participants (47.7%), their sexual lives have not changed, being higher the percentage for men (53.3%) than for women (45%). However, for the other half of participants, it has changed. For 14.4% of people, it has improved, being more women (16.3%) than men (10.4%). In a larger percentage (37.9%), they reported a deterioration, with similar percentages in men (36.3%) and women (38.7%). The gender differences between three options are statistically significant (χ2 = 12.640, p = 0.002, V = 0.093).

In case there was an improvement, the aspects more pointed were having a higher sexual frequency (76.4%), having spent more time fantasizing (33.7%), having diversified the type of sexual practices with their partner (30.8%), and having explored more through masturbation (24.5%). In addition, 8.7% highlights as positive not having felt pressured to have sex because of not being with the partner or not having privacy. Moreover, 2.9% mentioned having sexual relations with a person with whom they had not had it and 1.4% exploring other sexual orientations. For these variables, there are not statistically significant differences according to gender. However, it should be emphasized some aspects such as more men have found positive not feeling pressured to have sex or more women have explored more through masturbation (see Table 5).

Contrarily, among those who reported a deterioration of sexual life, the main aspects identified are as follows: the decrease in sexual frequency (82%), not having the privacy to masturbate calmly (26%) or to have sexual relations (21.3%) and in far distance, having sexual fantasies that caused discomfort (6.7%), feeling attracted to a new person (5.3%), having increased their sexual frequency (3.5%), being forced to have sex (2.6%), being unfaithful to their regular partner (0.5%), or having had same-sex intercourse while self-identifying as heterosexual people (0.2%). The only significant differences according to gender were found for the decrease in the frequency of sexual activity that was considered more negative by women (86.5%) than by men (71.9%) (χ2 = 16.928, p < 0.001, V = 0.176). However, the increase in frequency was considered more negative by men (7.6%) than by women (1.6%) (χ2 = 12.750, p < 0.001, V = 0.152) (see Table 5).

Predictive Variables of a Better or Worse Sex Life as a Consequence of COVID-19

To predict what variables affect the improvement or the deterioration of sexual life during the COVID-19 lockdown, a multinomial logistic regression was carried out. Our dependent variable had 3 levels, where sample had to response if their sexual life had improved, had deteriorated, or had not change at all. The option “lockdown has not altered my sex life” was used as the reference category. Eleven variables were included in this analysis: gender, age, sexual orientation, being in a relationship, privacy at home, living alone during the lockdown, how hard the lockdown has been and levels of stress, anxiety, depression, and boredom during that time. However, in order to summarize and comment just one model, we only present the five variables that are significative and meaningfully contribute to the full effect.

First of all, the goodness-of-fit of the model has to be checked. As the Pearson chi-square statistic has a value of 212.37 (204 df; p = 0.329) and it is not significant, we can assure that our model fits well the data. Furthermore, in Table 6, we can see how our final model is statistically better than the reference model, with lower AIC and BIC values, having our model a good adjustment.

Once the fit has been checked, Table 7 shows what variables are statistically significant. Firstly, when the lockdown has increased the sexual life, women experimented an improvement in this, with an odds ratio (OR) value of 1.52 (1/0.657). Furthermore, living with your partner has a positive effect on having a better sexual life. In fact, those who were living with their partner have a OR 2.15 times bigger than those who were not living with their partner in having a better sexual life. However, to have got some privacy at home do not have a significant effect on a better sexual life. Similarly, different levels of stress do not have a significative effect on having a good sexual life. Nevertheless, how people lived the lockdown has a significative effect on the improvement of their sexual experiences. Those who lived the lockdown as a fairly hard moment or as a hard moment affirmed that their sexual life did not improve, given that coefficients has a negative value. For example, those who lived the lockdown as a hard moment have an OR 2.45 (1/0.408) times bigger than those who not lived that moments as a hard time in not improving their sexual life.

Secondly, in Table 7, we can see variables that explain when lockdown deteriorated sexual life. In this context, gender is not a significative variable; thus, there are no differences between women and men. However, those who were living with their partner affirmed that their sexual life did not decay during the lockdown, with an OR of 1.61 (1/0.621), compared with people who were not living with their partners. Now, privacy at home gave to our sample the feeling that their sexual life did not decay, given that the Privacy coefficient has a negative value. In this case, the OR are 1.40 (1/0.713) times higher for people who had a private place at home and did not have a bad sexual life, compared to those who did not have that private place. Related to the stress variable, those who were very or quite stressed have an OR higher than 2 of having experienced a decrease in their sexual life during the lockdown, compared to those who did not experienced that levels of stress. Finally, all people who lived the lockdown as an unbearable o very hard situation agree that their sexual life suffered a deterioration, being really difficult for those who lived that situation as a very hard or a hard lockdown.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to analyze the impact of COVID-19 confinement on the sexual behavior of the Spanish general population. Regarding the confinement conditions and the social environment, the results have shown that the majority of the participants stayed in company, half with their partner and the other half with their parents and siblings or with their children. In any case, most of the times, they were the people with whom they already cohabitated, and in most cases their environment allowed a certain privacy to have sexual activity. This information should be considered since it is very likely that the higher or lower and more positive or negative impact of confinement on sexual life may depend on these type of determinants. In fact, ignoring them could be a serious limitation in any research. Other studies such as those by Jacob et al. (2020), Lehmiller et al. (2020), or Schiavi et al. (2020) also take them into account, although there are clear differences among the variables evaluated by one or the other studies.

Our results indicate that confinement in Spain has had an impact on sexual desire. It only remained the same for 29% of participants. Among those that changed, two opposite directions was revealed with almost identical percentages: for 36% of participants increased and for 35% decreased. There are also certain gender differences, increasing more in women and decreasing more in men. This differential effect in the same situation may seem contradictory, but it is not so much. In those who live apart from their partner, this confinement has exacerbated the desire towards the other, although it could not be satisfied due to the physical distance. In Li’s online study (Li et al., 2020), who find a decrease in the general sexual frequency, also point out that some aspects would increase the sexual frequency such as a longer time with the partner, fewer leisure opportunities, less workload, and less social or family obligations. However, others could also worsen it as a higher possibility of interpersonal conflicts, stress, lack of privacy or health problems. In China, where a decrease in sexual frequency is also observed (Li et al., Allen, M. S., & Walter, E. E. (2018). Health-related lifestyle factors and sexual dysfunction: A meta-analysis of population-based research. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 15(4), 458–475. Altena, E., Baglioni, C., Espie, C. A., Ellis, J., Gavriloff, D., Holzinger, B., et al. (2020). Dealing with sleep problems during home confinement due to the COVID-19 outbreak: practical recommendations from a task force of the European CBT-I Academy. Journal of Sleep Research. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsr.13052 Arafat, S. Y., Mohamed, A. A., Kar, S. K., Sharma, P., Kabir, R. (2020). Does COVID-19 pandemic affect sexual behaviour? A cross-sectional, cross-national online survey. Psychiatry Research, 289, 113050. Badger, R. L. (2017). Sexuality and stress. In S. Wadhwa (Ed.), Stress in the modern world: Understanding science and society, Vol. 1. (pp. 221–236). Greenwood Press/ABC-CLIO. Ballester-Arnal, R., & Gil-Llario, M. D. (2020). The virus that changed Spain: Impact of COVID-19 on people with HIV. AIDS and Behavior, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461–020–02877–3 Baltes, P.B. (1985). Psicología evolutiva del ciclo vital. Algunas observaciones convergentes sobre historia y teoría [Evolutionary psychology of the life cycle. Some converging observations on history and theory]. In A. Marchesi et al. (Eds.), Psicología Evolutiva, tomo 1 (pp. 247–267). Madrid: Alianza Editorial. Bancroft, J., Janssen, E., Strong, D., Carnes, L., Vukadinovic, Z., Long, S. (2003). The relation between mood and sexuality in heterosexual men. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 32, 217–230. Baumgartner, S. E., Sumter, S. R., Peter, J., Valkenburg, P. M., Livingstone, S. (2014). Does country context matter? Investigating the predictors of teen sexting across Europe. Computers in Human Behavior, 34, 157–164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.01.041 Brooks, S. K., Webster, R. K., Smith, L. E., Woodland, L., Wessely, S., Greenberg, N., et al. (2020). The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. The Lancet, 395, 912–920. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8 Colson, M. H. (2016). Sexual dysfunction and chronic illness. Part 1: Epidemiology, impact and significance. Sexologies: European Journal of Sexology and Sexual Health, 25(1), e5–e11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sexol.2016.01.007 Davis, J. T., & Hines, M. (2020). How large are gender differences in toy preferences? A systematic review and meta-analysis of toy preference research. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 49, 373–394. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-019-01624-7 Dowd, J. B., Adriano, L., Brazel, D. M., Rotondi, V., Block, P., Ding, X., et al. (2020). Demographic science aids in understanding the spread and fatality rates of covid-19. PNAS. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2004911117 Driemeyer, W., Janssen, E., Wiltfang, J., Elmerstig, E. (2017). Masturbation experiences of Swedish senior high school students: Gender differences and similarities. The Journal of Sex Research, 54(4–5), 631–641. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2016.1167814 Einat, T., & Chen, G. (2012). What’s love got to do with it? Sex in a female maximum-security prison. The Prison Journal, 92(4), 484–505. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0032885512457550 Fisher, W. (2015). Loneliness and sexuality. In A. Shaked & A. Rokach (Eds.), Addressing loneliness: Co**, prevention and clinical interventions. (pp. 34–50). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group. Gil-Llario, M. D., Giménez, C., Ballester-Arnal, R., Cárdenas-López, G., Durán-Baca, X. (2017). Gender, sexuality, and relationships in young Hispanic people. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 43(5), 456–462. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2016.1207732 Griffin-Shelley, E. (2003). The Internet and sexuality: A literature review 1983–2002. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 18(3), 355–370. https://doi.org/10.1080/1468199031000153955 Ho, C. S., Chee, C. Y., Ho, R. C. (2020). Mental health strategies to combat the psychological impact of COVID-19 beyond paranoia and panic. Annals of the Academy of Medicine, Singapore, 49(3), 155–160. Huang, Y., & Zhao, N. (2020). Generalized anxiety disorder, depressive symptoms and sleep quality during COVID-19 outbreak in China: a web-based cross-sectional survey. Psychiatry Research, 112954. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112954 Hussein, J. (2020). COVID-19: What implications for sexual and reproductive health and rights globally? Sexual and Reproductive Health Matters, 28, 1746065. https://doi.org/10.1080/26410397.2020.1746065 Ibarra, F. P., Mehrad, M., Di Mauro, M., Godoy, M. F. P., Cruz, E. G., Nilforoushzadeh, M. A., et al. (2020). Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the sexual behavior of the population. The vision of the east and the west. International Brazilian Journal of Urology, 46(Suppl 1), 104–112. https://doi.org/10.1590/s1677–5538.ibju.2020.s116 Instituto de Salud Carlos III (2020a). Informe sobre la situación de COVID-19 en España. Informe COVID-19 nº 23. 16 de abril de 2020 [Report on the situation of COVID-19 in Spain. COVID-19 Report No. 23. April 16, 2020]. https://www.isciii.es/QueHacemos/Servicios/VigilanciaSaludPublicaRENAVE/EnfermedadesTransmisibles/Documents/INFORMES/Informes%20COVID-19/Informe%20n%C2%BA%2023.%20Situaci%C3%B3n%20de%20COVID-19%20en%20Espa%C3%B1a%20a%2016%20de%20abril%20de%202020.pdf Instituto de Salud Carlos III (2020b). Análisis de los casos de COVID-19 en personal sanitario notificados a la RENAVE hasta el 10 de mayo en España. Informe a 29 de mayo de 2020 [Analysis of COVID-19 cases in health personnel notified to RENAVE until May 10 in Spain. Report as of May 29, 2020]. https://www.isciii.es/QueHacemos/Servicios/VigilanciaSaludPublicaRENAVE/EnfermedadesTransmisibles/Documents/INFORMES/Informes%20COVID-19/COVID-19%20en%20personal%20sanitario%2029%20de%20mayo%20de%202020.pdf Jacob, L., Smith, L., Butler, L., Barnett, Y., Grabovac, I., McDermott, D., et al. (2020). Challenges in the practice of sexual medicine in the time of COVID-19 in the United Kingdom. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 17(7), 1229–1236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2020.05.001 Jung, S. J., Jun, J. Y. (2020). Mental health and psychological intervention amid COVID-19 outbreak: Perspectives from South Korea. Yonsei Medical Journal, 61(4), 271–272. https://doi.org/10.3349/ymj.2020.61.4.271 Legido-Quigley, H., Mateos-García, J. T., Campos, V. R., Gea-Sánchez, M., Muntaner, C., McKee, M. (2020). The resilience of the Spanish health system against the COVID-19 pandemic. The Lancet Public Health. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30060-8 Lehmiller, J. J., Garcia, J. R., Gesselman, A. N., Mark, K. P. (2020). Less sex, but more sexual diversity: Changes in sexual behavior during the COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic. Leisure Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400.2020.1774016 Li, S., Wang, Y., Xue, J., Zhao, N., Zhu, T. (2020a). The impact of COVID-19 epidemic declaration on psychological consequences: A study on active weibo users. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(6), 2032. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17062032 Li, W., Li, G., **n, C., Wang, Y., Yang, S. (2020b). Challenges in the practice of sexual medicine in the time of COVID-19 in China. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 17, 1225–1228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2020.04.380 Li, Z., Ge, J., Yang, M., Feng, J., Qiao, M., Jiang, R., et al. (2020c). Vicarious traumatization in the general public, members, and non-members of medical teams aiding in COVID-19 control. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.03.007 Lichtenberg, P. A. (2014). Sexuality and physical intimacy in long-term care. Occupational Therapy In Health Care, 28(1), 42–50. https://doi.org/10.3109/07380577.2013.865858 Lippi, G., Henry, B. M., Bovo, C., Sanchis-Gomar, F. (2020). Health risks and potential remedies during prolonged lockdowns for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Diagnosis. https://doi.org/10.1515/dx-2020-0041 McCann, E., Donohue, G., de Jager, J., Nugter, A., Stewart, J., Eustace-Cook, J. (2019). Sexuality and intimacy among people with serious mental illness: A qualitative systematic review. JBI Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation Reports, 17(1), 74–125. https://doi.org/10.11124/JBISRIR-2017–003824 Mestre-Bach, G., Blycker, G. R., Potenza, M. N. (2020). Pornography use in the setting of the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 9(2), 181–183. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.2020.00015 Ministerio de Sanidad (2020). Actualización nº 220. Enfermedad por el coronavirus (COVID-19) [Update No. 200. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19)]. https://www.mscbs.gob.es/profesionales/saludPublica/ccayes/alertasActual/nCov/documentos/Actualizacion_220_COVID-19.pdf Mira, J. J. (2020). PANDEMIA COVID-19: Y ahora ¿qué? [PANDEMIC COVID-19: Now what?]. Journal of Healthcare Quality Research. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhqr.2020.04.001 Petersen, J. L., & Hyde, J. S. (2010). A meta-analytic review of research on gender differences in sexuality, 1993–2007. Psychological Bulletin, 136(1), 21–38. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017504 Qiu, J., Shen, B., Zhao, M., Wang, Z., **e, B., Xu, Y. (2020). A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Chinese people in the COVID-19 epidemic: implications and policy recommendations. General Psychiatry, 33, Article e100213. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/gpsych-2020–100213 Real Decreto 463/2020 [Gobierno de España]. Por el que se declara el estado de alarma para la gestión de la situación de crisis sanitaria ocasionada por el COVID-19. 14 de marzo de 2020 [By which the state of alarm is declared for the management of the health crisis situation caused by COVID-19. March 14, 2020]. https://www.boe.es/diario_boe/txt.php?id=BOE-A-2020-3692 Real Decreto-Ley 21/2020 [Gobierno de España]. De medidas urgentes de prevención, contención y coordinación para hacer frente a la crisis sanitaria ocasionada por el COVID-19. 9 de junio de 2020 [Of urgent prevention, containment and coordination measures to face the health crisis caused by COVID-19. June 9, 2020]. https://www.boe.es/diario_boe/txt.php?id=BOE-A-2020-5895 Reissing, E. D., Andruff, H. L., Wentland, J. J. (2012). Looking back: the experience of first sexual intercourse and current sexual adjustment in young heterosexual adults. Journal of Sex Research, 49(1), 27–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2010.538951 Richters, J., Butler, T., Schneider, K., Yap, L., Kirkwood, K., Grant, L., et al. (2012). Consensual sex between men and sexual violence in Australian prisons. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 41(2), 517–524. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-010-9667-3 Rokach, A. (2019). The effect of psychological conditions on sexuality: A review. Psychopharmacology, 29, 259–266. http://dx.doi.org/10.31031/pprs.2019.02.000534 Sanchez, T. H., Zlotorzynska, M., Rai, M., Baral, S. D. (2020). Characterizing the impact of COVID-19 on men who have sex with men across the United States in April, 2020. AIDS and Behavior, 24, 2024–2032. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007%2Fs10461–020–02894–2 Sandín, B., Valiente, R. M., García-Escalera, J., Chorot, P. (2020). Impacto psicológico de la pandemia de COVID-19: Efectos negativos y positivos en población española asociados al periodo de confinamiento nacional [Psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic: Negative and positive effects on the Spanish population associated with the period of national confinement]. Revista de Psicopatologia y Psicologia Clinica, 25(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.5944/rppc.27569 Schiavi, M. C., Spina, V., Zullo, M. A., Colagiovanni, V., Luffarelli, P., Rago, R., et al. (2020). Love in the time of COVID-19: Sexual function and quality of life analysis during the social distancing measures in a group of Italian reproductive-age women. The Journal of Sexual Medicine. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.jsxm.2020.06.006 Shaughnessy, K., Fudge, M., Byers, E. S. (2017). An exploration of prevalence, variety, and frequency data to quantify online sexual activity experience. The Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 26(1), 60–75. https://doi.org/10.3138/cjhs.261-A4 Shaughnessy, K., Byers, E. S., Walsh, L. (2011). Online sexual activity experience of heterosexual students: Gender similarities and differences. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 40(2), 419–427. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-010-9629-9 Sohrabi, C., Alsafi, Z., O’Neill, N., Khan, M., Kerwan, A., Al-Jabir, A., et al. (2020). World Health Organization declares global emergency: A review of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19). International Journal of Surgery, 76, 71–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.02.034 Taniguchi, H., Hisasue, S. I., Sato, Y. (2020). Challenges in the practice of sexual medicine in the time of COVID-19 in Japan. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 17(7), 1237–1238. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.jsxm.2020.05.031 Tenkorang, E. Y. (2018). Sexual behaviours in the context of the Ebola virus disease (EVD) in Ghana. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 20(7), 746–760. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2017.1372633 Wang, C., Pan, R., Wan, X., Tan, Y., Xu, L., Ho, C. S., et al. (2020). Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(5), e1729. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17051729 Weiss, N. H., Walsh, K., DiLillo, D. D., Messman-Moore, T. L., Gratz, K. L. (2019). A longitudinal examination of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and risky sexual behavior: Evaluating emotion dysregulation dimensions as mediators. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 48, 975–986. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-019-1392 Willoughby, B. J., Carroll, J. S., Nelson, L. J., Padilla-Walker, L. M. (2014). Associations between relational sexual behaviour, pornography use, and pornography acceptance among US college students. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 16(9), 1052–1069. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2014.927075 World Health Organization [WHO] (2020). Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): Weekly Epidemiological Update. 28 September 2020. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200928-weekly-epi-update.pdf?sfvrsn=9e354665_6 Yuksel, B., Ozgor, F. (2020). Effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on female sexual behavior. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.13193References

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study conception and design, material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by Rafael Ballester-Arnal, Juan E. Nebot-Garcia, and Maria Dolores Gil-Llario. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Rafael Ballester-Arnal, Estefanía Ruiz-Palomino, Juan E. Nebot-García, and Cristina Giménez-García, and revised by María Dolores Gil-Llario, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics Approval

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Universitat Jaume I (Castellón, Spain) and was performed in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

Informed Consent

Participants were informed about the objectives of the survey, completion times, benefits, and risks, as well as about the anonymity of the responses and the right to stop the survey in any point and for any reasons. Furthermore, participants were informed that the data collected would have been published in scientific journals in aggregate form. After reading all information, participants had to give their consent to participate in the online survey by clicking on the bottom “I accept to take part in the survey.”

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ballester-Arnal, R., Nebot-Garcia, J.E., Ruiz-Palomino, E. et al. “INSIDE” Project on Sexual Health in Spain: Sexual Life During the Lockdown Caused by COVID-19. Sex Res Soc Policy 18, 1023–1041 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-020-00506-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-020-00506-1