Abstract

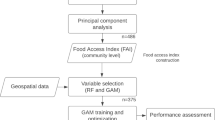

Cities in sub-Saharan Africa are characterised by rapid urban sprawl, which has implications for urban food accessibility. Urban sprawl results in inefficient structures of cities, and is often related to patterns of socioeconomic segregation. An important research gap in food accessibility studies is that these local socioeconomic imbalances are not considered in broad-scale studies. This research analyses how the dimensions of food access (physical, social and economic) relate to the food insecurity and dietary diversity of inhabitants of different socioeconomic groups in the rapidly growing Greater Kampala Metropolitan Area (Uganda). We use the Food Insecurity Experience Scale and Household Dietary Diversity Score to assess the overall state of food consumption. To measure physical accessibility, we geographically map the formal food system potential. A radar chart was used to visualise the vulnerability of different socioeconomic groups within the city food system. The results show that more established urban dwellers experience different access vulnerabilities than newly migrated residents, depending on their income. Lower income groups compensate their limited economic accessibility by participating in food sharing networks. Obtaining a better understanding of the dimensions of urban food accessibility can aid stakeholders in the urban food system in their policy making processes towards a more food secure and sustainable future.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

As wealthier groups reside on larger plots of land, this map corresponds to the dominant housing type in terms of area coverage and not in terms of population.

References

Atukunda, G., & Maxwell, D. (1996). Farming in the city of Kampala: Issues for urban management. African Urban Quarterly, 11(2–3), 264–276.

Ballard, T. J., Kepple, A. W., Cafiero, C., & Schmidhuber, J. (2014). Better measurement of food insecurity in the context of enhancing nutrition. Ernaehrungs Umschau, 61(2), 38–41.

Battersby, J., & Crush, J. (2014). Africa’s urban food deserts. Urban Forum, 25, 143–151.

Battersby, J., & Marshak, M. (2016). Map** the informal food economy of cape town South Africa. Hungry Cities Partnership Discussion Papers (No. 5).

Battersby, J., & Watson, V. (2019). Urban Food Systems Governance and Poverty in African Cities. Routledge.

Brunelli, C., Viviani, S., Ballard, T., Viviani, S., Nord, M., Grossi, M. Del, et al. (2014). Exploring gender-based disparities with the FAO Food Insecurity Experience Scale. In 2014 Global Forum on Gender Statistics. Mexico: Aguascalientes

Cafiero, C., Viviani, S., & Nord, M. (2018). Food security measurement in a global context: The food insecurity experience scale. Measurement, 116, 146–152.

Caley, D. (2016). The Nature and Measurement of Food Insecurity in Urban Slums: a Mixed-Methods Study in Kampala, Uganda. USA: New York University (PhD thesis)

Chaput, J. P., Gilbert, J. A., & Tremblay, A. (2007). Relationship between food insecurity and body composition in Ugandans living in urban Kampala. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 107(11), 1978–1982.

Charreire, H., Casey, R., Salze, P., Simon, C., Chaix, B., Banos, A., et al. (2010). Measuring the food environment using geographical information systems: A methodological review. Public Health Nutrition, 13(11), 1773–1785.

Cochran, W. G. (1963). Sampling Techniques (2nd ed.). John Wiley and Sons Inc.

Cohen, M. J., & Garrett, J. L. (2010). The food price crisis and urban food (in)security. Environment and Urbanization, 22(2), 467–482.

Crush, J. (2014). Approaching food security in cities of the Global South. In S. Parnell & S. Oldfield (Eds.), The Routledge Handbook on Cities of the Global South (pp. 543–555). Routledge.

Crush, J., & Battersby, J. (2016). Rapid Urbanisation, Urban Food Deserts and Food Security in Africa. Springer International Publishing.

Crush, J., & Riley, L. (2017). Urban Food Security Rural Bias and the Global Development Agenda. Hungry Cities Partnership Discussion Papers (No. 11).

Davis, J., Magadzire, N., Hemerijckx, L. M., Maes, T., Durno, D., Kenyana, N., et al. (2022). Precision approaches to food insecurity: A spatial analysis of urban hunger and its contextual correlates in an African city. World Development, 149, 105694.

FAO. (2010). Guidelines for measuring household and individual dietary diversity. (G. Kennedy, T. Ballard, & M. C. Dop, Eds.). Rome: FAO.

FAO. (2016). Methods for estimating comparable prevalence rates of food insecurity experienced by adults throughout the world. (C. Cafiero, M. Nord, S. Viviani, M. E. Del Grossi, T. Ballard, A. Kepple, et al., Eds.) (Vol. 1). Rome: FAO.

FAO, Ifad, UNICEF, WFP, & WHO. (2017). The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2017 - Building resilience for peace and food security. FAO.

Frayne, B., & McCordic, C. (2015). Planning for food secure cities: Measuring the influence of infrastructure and income on household food security in Southern African cities. Geoforum, 65, 1–11.

Gallaher, C. M., Kerr, J. M., Njenga, M., Karanja, N. K., & WinklerPrins, A. M. G. A. (2013). Urban agriculture social capital and food security in the Kibera slums of Nairobi Kenya. Agriculture and Human Values, 30(3), 389–404.

Hamidi, S. (2020). Urban sprawl and the emergence of food deserts in the USA. Urban Studies, 57(8), 1660–1675.

Hansen, W. G. (1959). How accessibility shapes land use. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 25(2), 73–76.

Hemerijckx, L.-M., Van Emelen, S., Rymenants, J., Davis, J., Verburg, P. H., Lwasa, S., & Van Rompaey, A. (2020). Upscaling household survey data using remote sensing to map socioeconomic groups in Kampala Uganda. Remote Sensing, 12(20), 3468.

Heynen, N., Kurtz, H. E., & Trauger, A. (2012). Food justice hunger and the city. Geography Compass, 6(5), 304–311.

Janusz, K., Kesteloot, C., Vermeiren, K., & Van Rompaey, A. (2019). Daily mobility, livelihoods and transport policies in Kampala, Uganda: A Hägerstrandian analysis. Tijdschrift Voor Economische En Sociale Geografie, 110(4), 412–427.

Karg, H., Drechsel, P., Akoto-Danso, E., Glaser, R., Nyarko, G., & Buerkert, A. (2016). Foodsheds and city region food systems in two West African cities. Sustainability, 8, 1175.

Kuusaana, E. D., & Eledi, J. A. (2015). As the city grows, where do the farmers go? Understanding Peri-urbanization and food systems in Ghana - Evidence from the Tamale Metropolis. Urban Forum, 26(4), 443–465.

Leite, M. A., de Assis, M. M., & do Carmo, A. S., Nogueira, M. C., Netto, M. P., & Mendes, L. L. (2020). Inequities in the urban food environment of a Brazilian city. Food Security, 13(3), 39–549.

Mackay, H. (2019). Food sources and access strategies in Ugandan secondary cities: An intersectional analysis. Environment and Urbanization, 31(2), 375–396.

OpenStreetMap contributors. (2020). Spatial data points for marketplaces, markets and supermarkets in Kampala. https://overpass-turbo.eu/. Accessed 6 March 2020

Páez, A., Mercado, R. G., Farber, S., Morency, C., & Roorda, M. (2010). Relative accessibility deprivation indicators for urban settings: Definitions and application to food deserts in montreal. Urban Studies, 47(7), 1415–1438.

Poelmans, L., & Van Rompaey, A. (2009). Detecting and modelling spatial patterns of urban sprawl in highly fragmented areas: A case study in the Flanders-Brussels region. Landscape and Urban Planning, 93(1), 10–19.

Pottier, J. (2015). Co** with urban food insecurity: Findings from Kampala Uganda. Journal of Modern African Studies, 53(2), 217–241.

Sabiiti, E. N., & Katongole, C. B. (2014). Urban agriculture: A response to the food supply crisis in Kampala city, Uganda. In B. Maheshwari, R. Purohit, H. Malano, V. P. Singh, & P. Amerasinghe (Eds.), The Security of Water, Food, Energy and Liveability of Cities, 233–242. Dordrecht: Springer Science+Business Media.

Shaw, H. J. (2016). Food deserts: Towards the development of a classification. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography, 88(2), 231–247.

Smets, P., & Salman, T. (2008). Countering urban segregation: Theoretical and policy innovations from around the globe. Urban Studies, 45(7), 1307–1332.

Swanepoel, J. W., Van Niekerk, J. A., & D’Haese, L. (2017). The socio-economic profile of urban farming and non-farming households in the informal settlement area of the Cape Town Metropole in South Africa. South African Journal of Agricultural Extension, 45(1), 131–140.

Swindale, A., & Bilinsky, P. (2006). Household Dietary Diversity Score (HDDS) for measurement of household food access: Indicator guide. Washington, D.C.: FHI 360/FANTA.

Tevera, D., & Simelane, N. (2014). Food for the urban poor: Safety nets and food-based social protection in Manzini, Swaziland. Urban Forum, 25, 241–252.

UBOS. (2016a). Uganda National Population and Housing Census 2014 - Main Report. Kampala, Uganda.

UBOS. (2016b). 2016 Statistical Abstract. Kampala, Uganda.

UBOS. (2018). Uganda National Household Survey Report 2016/2017. Kampala, Uganda.

UN-DESA. (2015). World Urbanization Prospects: The 2014 Revision. United Nations.

UN-DESA. (2017). World Population Prospects 2017 - Volume II: Demographic Profiles. New York: United Nations.

Van Vliet, J., Birch-Thomsen, T., Gallardo, M., Hemerijckx, L.-M., Hersperger, A. M., Li, M., et al. (2020). Bridging the rural-urban dichotomy in land use science. Journal of Land Use Science, 15(5), 585–591.

Vermeiren, K., Adiyia, B., Loopmans, M., Tumwine, F. R., & Van Rompaey, A. (2013). Will urban farming survive the growth of African cities: A case-study in Kampala (Uganda)? Land Use Policy, 35, 40–49.

Vermeiren, K., Van Rompaey, A., Loopmans, M., Serwajja, E., & Mukwaya, P. (2012). Urban growth of Kampala, Uganda: Pattern analysis and scenario development. Landscape and Urban Planning, 106(2), 199–206.

Vermeiren, K., Vanmaercke, M., Beckers, J., & Van Rompaey, A. (2016). ASSURE: A model for the simulation of urban expansion and intra-urban social segregation. International Journal of Geographical Information Science, 30(12), 2377–2400.

Wambogo, E. A., Ghattas, H., Leonard, K. L., & Sahyoun, N. R. (2018). Validity of the Food Insecurity Experience Scale for Use in Sub-Saharan Africa and Characteristics of Food-Insecure Individuals. Current Developments in Nutrition, 2(9), 1–10.

Wanyama, R., Gödecke, T., Chege, C. G. K., & Qaim, M. (2019). How important are supermarkets for the diets of the urban poor in Africa? Food Security, 11(6), 1339–1353.

Warshawsky, D. N. (2016). Civil Society and the Governance of Urban Food Systems in Sub-Saharan Africa. Geography Compass, 10(7), 293–306.

Yeudall, F., Sebastian, R., Cole, D. C., Ibrahim, S., Lubowa, A., & Kikafunda, J. (2007). Food and nutritional security of children of urban farmers in Kampala Uganda. Food and Nutrition Bulletin, 28(2), 237–246.

Yiga, P., Ogwok, P., Seghers, J., Achieng, J., Auma, M. D., Matthys, C., et al. (2020). Determinants of dietary and physical activity behaviors among women of reproductive age in urban Uganda, a qualitative study. Public Health Nutrition Journal, 24(12), 3624–3636.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the colleagues and data collectors from the Urban Action Lab at Makerere University and KU Leuven: Teddy Kisembo, Judith Mbabazi, Gloria Nsangi, Hakimu Sseviiri, Disan Byarugaba and Desmond Khisa Situma. Moreover, we thank the local council leaders of the visited parishes in the GKMA for their guidance on the field.

Funding

This research fulfils the first work package in project 11C6120N titled ‘Spatial analysis of food systems transformations in rapidly growing African cities’, funded by Fonds Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek (FWO) Vlaanderen (grant number 11C6120N). In addition, this work was supported by the Food4Cities research project, funded by the LEAP-Agri program of the European Union.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed significantly to the intellectual development of the article and approved the final version. The first named author took the lead in framing and writing the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

The household survey protocol was approved with approval number G-2019 06 1664 by the KU Leuven Social and Societal Ethics Committee (SMEC) on June 19th 2019.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Appendices

Appendix 1 Survey protocol

1. A. Socioeconomic variables used for defining the SEC

Categorical variables are indicated as either binary (B), ordinal (O) or nominal (N). Table from Hemerijckx et al., (2020, p.7).

Variable Collection | Numeric Variables | Categorical Variables |

|---|---|---|

Household characteristics | Total number of household members Number of children (< 18 y.o.) Number of adult women (≥ 18 y.o.) Average commuting time Average education level Number of years lived in Kampala | Household tribe (N) Most spoken language (N) Urban agricultural activity (B) Housing type (N) Roofing type (N) Toilet type (N) Road type in front of home (N) Water source (13 dummy var.) (B) Energy source (9 dummy var.) (B) Cooking energy source (7 dummy var.) (B) |

Neighborhood characteristics | Distance to nearest water source | Parish name (N) Neighborhood reputation (O) Neighborhood cleanliness (O) Neighborhood safety (O) Gated home infrastructure (O) Tarmacked road infrastructure (O) Flooding prevalence (O) Overall happiness in neighborhood (O) |

Income and ownership | Income (2 var.) Workers employed at household Food expenditure (2 var.) Vehicle ownership (5 var.) | Tenure status (N) Ownership of air-conditioning (B) Ownership of a radio (B) Ownership of a television (B) Online activity (3 var.) (B) Ownership of a telephone (3 var.) (B) |

1. B. Food Insecurity Experience Scale questionnaire

FAO questionnaire (Ballard et al., 2014, p.39), English version. Answers are yes/no.

During the last 12 months, was there a time when:

Question number | Variable | Survey Question |

|---|---|---|

1 | WORRIED | You were worried you would not have enough food to eat because of a lack of money or other resources? |

2 | HEALTHY | You were unable to eat healthy and nutritious food because of a lack of money or other resources? |

3 | FEWFOOD | You ate only a few kinds of foods because of a lack of money or other resources? |

4 | SKIPPED | You had to skip a meal because there was not enough money or other resources to get food? |

5 | ATELESS | You ate less than you thought you should because of a lack of money or other resources? |

6 | RUNOUT | Your household ran out of food because of a lack of money or other resources? |

7 | HUNGRY | You were hungry but did not eat because there was not enough money or other resources for food? |

8 | WHLDAY | You went without eating for a whole day because of a lack of money or other resources? |

1. C. Household Dietary Diversity Score questionnaire

FAO questionnaire (FAO, 2010, p.7), English version. Answers are yes/no for each food group.

Please describe the foods (meals and snacks) that you ate or drank yesterday during the day and night, whether at home or outside the home. Start with the first food or drink of the morning.

Question number | Food group | Examples |

|---|---|---|

1 | CEREALS | corn/maize, rice, wheat, sorghum, millet or any other grains or foods made from these (e.g. bread, noodles, porridge or other grain products) + insert local foods e.g. ugali, nshima, porridge or paste |

2 | WHITE ROOTS AND TUBERS | white potatoes (in any form), white yam, white cassava, Matooke, Irish Potatoes, or other foods made from roots |

3 | VITAMIN A RICH VEGETABLES AND TUBERS | pumpkin, carrot, squash, or sweet potato that are orange inside + other locally available vitamin A rich vegetables (e.g. red sweet pepper) |

4 | DARK GREEN LEAFY VEGETABLES | dark green leafy vegetables, including wild forms + locally available vitamin A rich leaves such as amaranth, cassava leaves, kale, spinach |

5 | OTHER VEGETABLES | other vegetables (e.g. tomato, onion, eggplant) + other locally available vegetables |

6 | VITAMIN A RICH FRUITS | ripe mango, cantaloupe, apricot (fresh or dried), ripe papaya, dried peach, watermelon, passion fruit and 100% fruit juice made from these + other locally available vitamin A rich fruits |

7 | OTHER FRUITS | other fruits, including wild fruits and 100% fruit juice made from these |

8 | ORGAN MEAT | liver, kidney, heart or other organ meats or blood-based foods |

9 | FLESH MEATS | beef, pork, lamb, goat, rabbit, game, chicken, duck, other birds, insects |

10 | EGGS | eggs from chicken, duck, guinea fowl or any other egg |

11 | FISH AND SEAFOOD | fresh or dried fish or shellfish |

12 | LEGUMES, NUTS AND SEEDS | dried beans, dried peas, lentils, nuts, seeds or foods made from these (eg. hummus, peanut butter) |

13 | MILK AND MILK PRODUCTS | milk, cheese, yogurt or other milk products |

14 | OILS AND FATS | oil, fats or butter added to food or used for cooking |

15 | SWEETS | sugar, honey, sweetened soda or sweetened juice drinks, sugary foods such as chocolates, candies, cookies and cakes |

16 | SPICES, CONDIMENTS, BEVERAGES | spices (black pepper, salt), condiments (soy sauce, hot sauce), coffee, tea, alcoholic beverages |

1. D. Food accessibility

Variable | Survey Question |

|---|---|

Food expenditure | What is your household’s average daily expenditure on food? |

Household income | What is the total monthly household income in UGX? |

Proximity to most used food source | How long does it take you to travel to [most frequented market by respondent]? |

Urban agricultural activity | Does this household produce any kind of food or other agricultural products, whether sold or consumed? |

Food sharing activity | Do you receive or give food from/to neighbours, family members or other sources? |

Tribe | Which tribe (or if not Ugandan: nationality) do the members of your household identify as? |

Appendix 2 Sampling information (Hemerijckx et al., 2020)

Between July and December 2019, six surveyors approached homes in 15 contrasting parishes (the small administrative units, SAU) of the Greater Kampala Metropolitan Area (GKMA). We aimed to survey households at SAU that are contrasting both in terms of their location within the GKMA and in terms of socioeconomic population dynamics. The socioeconomic information was based on prior geographic research on the population of the SAU by Vermeiren et al. (2016), combined with consulting local experts at the Urban Action Lab of Makerere University. In addition, to select the final sampled parishes, we considered neighbourhood accessibility and surveyor safety. The sample size was thus limited by the practical access to the SAU. Within the selected SAU, a snowball strategy was adopted to sample households. This implied that a local council representative, after giving their informed consent, led the surveyors to households and assisted surveyors to clarify the purpose of the research.

As such, a convenience sampling method was adopted on the field. However, as a guideline to target sample size we calculated that with a desired confidence interval of 95%, the sample size of 541 households results in a margin of error of 1.97% based on Cochran's (1963) sample size formula for estimating prevalence:

where:

-

n is the sample size (541 households, with 2487 individuals).

-

p is the population proportion (assumed at 0.5 for complete uncertainty).

-

Z the Z-score (1.96 for a confidence interval of 95%).

-

e is the error margin (1.97%).

The final sample contained 541 households. Information was gathered on a total of 2487 individuals within these households. Prior to clustering the households by socioeconomic group, 16 households that exceeded a threshold of 37% of missing data (i.e. the respondent did not respond to over 37% of the survey questions) were excluded from analysis. Participants had an average of 4.25% missing data (SD = 10.91%, range = 0–95%). This threshold minimises the number of households that would be excluded, while also balancing adequate sampling per participant. This way, 525 households were included in the final dataset that was used for the present study. Figure 6 below shows the spatial distribution of the sampled households compared to the formal food markets as registered on OpenStreetMap.

Appendix 3 Comparison of the food group categories used in the FAO dietary diversity questionnaire (16 food groups), the required aggregation to obtain the Household Dietary Diversity Score (HDDS, 12 food groups) (FAO, 2010), and the Uganda food consumption census data from the national household survey 2016/2017 (9 food groups) (UBOS, 2018)

FAO dietary diversity questionnaire | HDDS aggregation | Uganda national household survey |

|---|---|---|

Cereals | Cereals | Staples (cereals, roots and tubers) |

White roots and tubers | White roots and tubers | |

Vitamin A rich vegetables and tubers | Vegetables | Vegetables |

Dark green leafy vegetables | ||

Other vegetables | ||

Vitamin A rich fruits | Fruits | Fruits |

Other fruits | ||

Organ meat | Meat | Meat, fish, eggs |

Flesh meats | ||

Eggs | Eggs | |

Fish and seafood | Fish and seafood | |

Legumes, nuts and seeds | Legumes, nuts and seeds | Pulses and nuts |

Milk and milk products | Milk and milk products | Milk |

Oils and fats | Oils and fats | Oil and fats |

Sweets | Sweets | Sugar |

Spices, condiments, beverages | Spices, condiments, beverages | Spices |

Appendix 4 Results of the Rasch model

Item | Severity | Standard Error | Infit | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

SEC | EH | EL | NM | NL | EH | EL | NM | NL | EH | EL | NM | NL |

WORRIED | -2.32 | -1.75 | -1.55 | -1.61 | 0.31 | 0.41 | 0.38 | 0.30 | 0.99 | 1.10 | 1.14 | 1.12 |

HEALTHY | -0.78 | -0.72 | -1.10 | -0.20 | 0.31 | 0.38 | 0.36 | 0.26 | 1.08 | 1.68 | 1.14 | 1.51 |

FEWFOOD | -1.70 | -1.35 | -1.55 | -1.11 | 0.31 | 0.40 | 0.38 | 0.28 | 0.99 | 0.75 | 0.82 | 0.83 |

SKIPPED | 0.51 | -0.36 | 0.32 | 0.13 | 0.35 | 0.37 | 0.35 | 0.25 | 0.82 | 0.79 | 0.97 | 0.83 |

ATELESS | -0.36 | -0.84 | -0.48 | -0.49 | 0.32 | 0.38 | 0.34 | 0.26 | 1.06 | 0.83 | 0.89 | 0.87 |

RUNOUT | 1.08 | 0.81 | 0.94 | 0.55 | 0.38 | 0.38 | 0.36 | 0.25 | 1.26 | 0.62 | 0.71 | 0.82 |

HUNGRY | 1.08 | 1.40 | 0.62 | 0.97 | 0.38 | 0.39 | 0.35 | 0.25 | 0.86 | 0.83 | 1.05 | 0.83 |

WHLDAY | 2.50 | 2.82 | 2.78 | 1.76 | 0.48 | 0.51 | 0.50 | 0.27 | 1.12 | 1.25 | 1.19 | 1.25 |

SEC | Rasch reliability |

|---|---|

EH | 0.748 |

EL | 0.751 |

NM | 0.732 |

NL | 0.715 |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hemerijckx, LM., Janusz, K., Van Emelen, S. et al. Food accessibility of different socioeconomic groups in sub-Saharan African cities: a mixed-method analysis in Kampala, Uganda. Food Sec. 14, 677–694 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-021-01248-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-021-01248-7