Abstract

Introduction

Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) is a neuromuscular disease caused by deletions and/or mutations in the survival of motor neuron 1 (SMN1) gene. Risdiplam, the first and only oral SMN2 pre-mRNA splicing modifier, is US Food and Drug Administration-approved for the treatment of pediatric and adult patients with SMA. For patients with SMA, long-term adherence to and persistence with an SMA treatment may be important for achieving maximum clinical benefits. However, real-world evidence on patient adherence to and persistence with risdiplam is limited.

Methods

This retrospective study examined real-world adherence and persistence with risdiplam from a specialty pharmacy in patients with SMA over a 12-month period. Adherence was estimated by using proportion of days covered (PDC) and was calculated over variable (time between first and last fill) and fixed (time from first fill to study period end) intervals. Persistence was defined as no gap in supply ≥ 90 days. Patients were included if the time between the index date and study observation period was ≥ 12 months, if they initiated risdiplam between August 2020 and September 2022, received ≥ 2 risdiplam fills, and had an SMA diagnosis associated with a risdiplam fill. Subgroup analyses of risdiplam adherence and persistence were performed by age and primary payer type.

Results

The proportion of patients (N = 1636) adherent at 12 months based on variable and fixed interval PDC was 93% and 79%, respectively. Adherence was high among patients on commercial insurance, Medicaid, or Medicare (range 86–96%). Mean persistence was 330.4 days. The highest proportion of patients who were persistent were on Medicaid (81%).

Conclusion

These findings demonstrate that patient adherence to and persistence with risdiplam treatment were high, including across all subgroups tested.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this study? |

Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) is a genetic, progressive neuromuscular disease that affects both pediatric and adult patients. As a result of the progressive nature of SMA, a short period without treatment can have lasting effects on motor neuron loss. Currently, there is little evidence regarding real-world patient adherence to and persistence with risdiplam, a US Food and Drug Administration-approved disease-modifying therapy for the treatment of SMA. |

The objective of this study was to determine patient-level adherence to and persistence with risdiplam over a 12-month time frame using data from a specialty pharmacy. |

What was learned from the study? |

The proportion of patients adherent calculated by the variable and fixed interval methods for proportion of days covered showed that 93% and 79% were adherent at 12 months, respectively. The mean persistence with risdiplam was 330.4 days. |

The findings from this study demonstrated that mean adherence rates and persistence remained relatively high at 12 months. These results may inform future decisions regarding the selection of disease-modifying therapies for individuals with SMA. |

Introduction

Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) is a progressive, genetic neuromuscular disease caused by biallelic mutations of the survival of motor neuron 1 (SMN1) gene [1,2,3]. A second paralogous SMN gene, SMN2, produces low levels of functional SMN protein, which are insufficient to compensate for the deficiency in SMN1, consequently leading to motor neuron loss [1, 4].

Three disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) designed to increase SMN protein levels are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of SMA. In 2016, nusinersen (SPINRAZA®; Biogen) an intrathecally administered, antisense oligonucleotide that modifies SMN2 pre-mRNA splicing was approved for pediatric and adult patients with SMA [5]. Treatment is initiated with 3 loading doses set at 14-day intervals, and a fourth loading dose is administered 30 days after the third dose. Maintenance doses are required once every 4 months thereafter. In 2019, onasemnogene abeparvovec (ZOLGENSMA®; Novartis Gene Therapies, Inc), an adeno-associated virus vector-based gene therapy, was approved for pediatric patients < 2 years of age. Onasemnogene abeparvovec is administered as a one-time infusion delivering a functional copy of the SMN1 gene to motor neurons [6]. Thereafter in 2020, risdiplam (EVRYSDI®; Genentech, Inc), a once daily, oral SMN2 pre-mRNA splicing modifier was approved. Risdiplam is indicated for the treatment of pediatric and adult patients with SMA [7, 8]. With the availability and effectiveness of DMTs, the traditional classifications of SMA based on age of symptom onset (types 0–4) are becoming obsolete. As such, a new classification system for SMA has emerged that is based on motor function achievement (e.g., non-sitters, sitters, and walkers) [9, 10].

As a result of the progressive nature of the disease, a short period without treatment can have lasting effects on motor neuron loss [11]. Compared with natural history studies, individuals receiving SMA DMTs exhibit prolonged overall survival and enhanced motor function [12,13,14]. Emerging real-world evidence demonstrated long-term DMT treatment may lead to better outcomes such as increased mobility and improved respiratory outcomes [15,16,17]. Furthermore, quality-of-life improvements have been observed in individuals with SMA taking DMTs, particularly those who were receiving therapy for a longer duration [18, 19]. Long-term adherence may also reduce associated comorbidities and hospitalizations, which may subsequently reduce healthcare costs and healthcare resource utilization [20,21,22,23].

Some individuals with SMA and their caregivers may prefer an oral therapy [24]; however, no data exist regarding real-world patient adherence to and persistence with risdiplam, the only oral at-home treatment for SMA. This retrospective study examined real-world risdiplam adherence and persistence over a 12-month period for individuals with SMA in the USA using a specialty pharmacy.

Methods

Data Source and Patient Selection

A retrospective analysis was conducted to evaluate patient-level adherence to and persistence with risdiplam over a 12-month period. Patient-level data were sourced from a specialty pharmacy that captures ≥ 98% of pharmacy claims for patients treated with risdiplam in the USA. The data included de-identified patient demographics and clinical characteristics (e.g., diagnosis code), prescription information, as well as initial fill and refill information (e.g., fill status/dates, refill count).

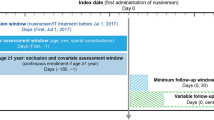

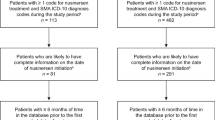

Data were available between August 7, 2020 and September 11, 2022. Patients were included if the time between first risdiplam fill (index date) and September 11, 2022 was ≥ 12 months and if they had received ≥ 2 fills of risdiplam associated with an SMA diagnosis. At least 2 risdiplam fills were required to ensure patients were not receiving a one-time fill. International Classification of Diseases, Ninth and Tenth Revisions (ICD-9 and ICD-10) diagnosis codes for SMA included 335.0x and 335.1x (ICD-9) and G12.0, G12.1, G12.8 and G12.9 (ICD-10).

Ethical Approval

To protect patient privacy, all data presented are compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. A data use agreement with the specialty pharmacy allows for publication of results of analyses using their data in manuscripts. Institutional review board review does not apply because only deidentified data were included.

Study Measures, Outcomes, and Statistical Analyses

Data on patient demographics were assessed at first date of risdiplam fill. Prescriber region and primary payer type were assessed at first and last risdiplam fill. Study outcomes were risdiplam adherence and persistence at 12 months. Subgroup analyses by age and primary payer type were performed to further investigate risdiplam adherence and persistence. Descriptive statistics of the data were performed over the 12-month study period.

Treatment Adherence

Adherence was measured at the patient level using the proportion of days covered (PDC) [25,26,27]. PDC assessed the proportion of days an individual had medication available over a specific time frame. PDC was calculated as (sum of days covered in time frame) ÷ (number of days in time frame) × 100. A sensitivity analysis of adherence was conducted, in which the medication possession ratio (MPR) was calculated. MPR was defined as the proportion of time that the medication was available to the patient. MPR was calculated as (sum of days supply of medication in a given time frame) ÷ (number of days in time frame) × 100. Patients were considered adherent to risdiplam if the PDC or MPR was ≥ 80%.

PDC and MPR were calculated using variable and fixed intervals [25, 28]. The variable interval used the time between the first and last fills representing the time patients were on treatment. The fixed interval used the time from the first fill to the end of the 12-month study period, regardless of whether treatment was discontinued. The variable interval approach provides an evaluation of patient adherence during a known time period when a patient is being prescribed medication and is on treatment. In contrast, the fixed interval approach assumes a patient is prescribed the medication over the entire analysis period. Variable and fixed interval approaches may skew adherence estimates toward higher and lower values, respectively. Therefore, adherence results are provided as a range, where fixed interval PDC and MPR serve as the lower bound for adherence and variable interval PDC and MPR serve as the upper bound.

Adherence rates (mean and median) and the proportion of patients who were adherent at 12 months (out of the total patients in each cohort) were reported for the overall cohort. Additional adherence and persistence analyses were carried out where patients were stratified by age and primary payer type.

Treatment Persistence

Persistence was defined as no gap in supply ≥ 90 days during the post-index period. This supply gap was selected on the basis of the overall distribution of fills, which indicated that most patients had truly discontinued (i.e., non-persistent) and had not restarted treatment after a ≥ 90 day gap in supply. To assess robustness of results, a sensitivity analysis in which persistence was defined as no gap in supply ≥ 60 days was also performed. Persistence in days (mean and median) and the proportion of patients who were persistent with risdiplam at 12 months were reported stratified by age and primary payer type.

Results

Patient Characteristics

A total of 1636 individuals with SMA were included in the analysis (Fig. 1). ICD-10 codes G12.1 (n = 902 [57%]), G12.9 (n = 354 [22%]), and G12.0 (n = 323 [20%]) comprised the majority of diagnosis codes at first risdiplam fill. The mean (standard deviation [SD]) age at first risdiplam fill was 23.3 (16.9) years, and nearly half (n = 804 [49%]) were ≥ 18 years of age.

Primary payer type at first risdiplam fill mainly consisted of commercial (n = 722 [44%]), Medicaid (n = 569 [35%]), or Medicare (n = 312 [19%]) coverage (Fig. 1). Primary payer type at last risdiplam fill was similar and consisted primarily of commercial (n = 733 [45%]), Medicaid (n = 576 [35%]), or Medicare (n = 320 [20%]). Over half of the prescribers were located in the South or Midwest at first risdiplam fill (n = 995 [61%]) and at last risdiplam fill (n = 998 [61%]).

Patient Adherence to Risdiplam Treatment

PDC: Variable Interval

The mean (SD) PDC calculated using a variable interval was 95% (10%) at 12 months (Table 1), and the proportion of patients who were adherent to treatment at 12 months was 93% (Fig. 2). When stratified by age categories, the PDC was consistently high across age groups (Table 2). Across all age categories, the mean PDC (SD) was 94–95% (9–11%) and the proportion of patients who were adherent at 12 months ranged from 91% to 95%. PDC was also high regardless of primary payer type. Patients on Medicare had the highest mean (SD) PDC (96% [9%]) followed by those on commercial insurance (95% [9%]) and Medicaid (93% [11%]) (Table 2).

PDC: Fixed Interval

At 12 months, the mean (SD) PDC calculated using a fixed interval was 87% (22%) (Table 1), and the proportion of patients who were adherent to risdiplam was 79% (Fig. 2). When stratified by age categories, the mean PDC calculated at a fixed interval was consistently high across all age groups, similar to that of the variable interval (Table 2). Across all age categories, the mean (SD) PDC ranged from 86% to 92% (17–23%). Patients aged 3–5 years exhibited the highest mean (SD) PDC (92% [17%]) followed by patients aged 6–17 (87% [21%]), 0–2 (87% [23%]), and ≥ 18 years (86% [23%]). The proportion of patients who remained adherent across age groups ranged from 77% to 90%. Patients insured with Medicare at last risdiplam fill had the highest mean (SD) PDC of 88% (21%), compared with patients receiving commercial insurance (87% [21%]) or Medicaid (86% [21%]; Table 2).

Sensitivity Analysis

MPR: Variable Interval

A sensitivity analysis was conducted using MPR over 12 months. The mean (SD) MPR calculated at a variable interval was 95% (10%) overall (Table 1), and the proportion of patients who were adherent to risdiplam was 93% (Supplementary Fig. S1). When stratified by age categories, the mean (SD) MPR was consistently high across all age groups, from 95% to 96% (9–11%) (Table 3). At last risdiplam fill, the MPR remained relatively high regardless of insurance coverage (Table 3). The mean (SD) MPR ranged from 94% to 96% (8–11%) across commercial insurance, Medicaid, and Medicare.

MPR: Fixed Interval

For the overall population, the mean (SD) MPR calculated at a fixed interval was 88% (22%) at 12 months (Table 1), and the proportion of patients adherent was 79% (Supplementary Fig. S1). Similar to the mean MPR calculated at a variable interval, the mean MPR calculated at a fixed interval remained high irrespective of age (Table 3). The analysis revealed a mean (SD) range of 87–93% (17–23%) across age groups. In addition, the mean (SD) MPR ranged from 88% to 89% (22%) across patients covered by commercial insurance, Medicaid, and Medicare (Table 3).

Patient Persistence with Risdiplam Treatment

The majority of patients (80%) included in this study were considered persistent with risdiplam treatment at 12 months (Fig. 2). For the overall patient population, the mean (SD) treatment persistence using the ≥ 90-day gap rule was 330.4 (80.8) days at 12 months (Table 1). There were 65 patients (4%) who restarted risdiplam treatment after the 90-day gap; among these patients the mean (SD) treatment gap was 173.3 (145.1) days. Patients aged 3–5 years had the highest mean (SD) persistence of 348.2 (63.3) days and those insured by Medicaid had the highest percent persistence with risdiplam (81%; Table 4).

Sensitivity Analysis: ≥ 60-Day Gap Rule

When the ≥ 60-day gap rule was used, the mean (SD) treatment persistence was 328.0 (83.5) days at 12 months for the entirety of the patients included, and 79% were considered persistent with risdiplam using this rule. There were 107 patients (7%) who restarted risdiplam treatment after the gap, and the mean (SD) treatment gap was 155.0 (134.7) days. Patients aged 3–5 years had the highest mean (SD) persistence (345.5 [68.5]) and those commercially insured had the highest percent persistence with risdiplam (80%; Table 5).

Discussion

Study Findings and Implications

High adherence to and persistence with risdiplam were observed among patients with SMA over the 12-month study period, regardless of age and insurance coverage. For both the fixed and variable PDC methodologies, mean PDC values were high (87% and 95%, respectively). To our knowledge, this is the first study that evaluates real-world risdiplam adherence and persistence.

The high adherence and persistence observed in this study may be attributed to the route of administration and setting for drug administration. Risdiplam is a daily, oral medication that can be taken at home without requiring the scheduling of appointments and travel to a specialized clinic, which could delay treatment [29]. Adherence was high in all age groups examined. In younger age groups, high adherence may have been due to parents’ view that treatment for their child was not a choice, but a necessity as the alternative would be death or severe disability [30]. For older patients, their desire to maintain or improve their current functional ability may be a motivator to adhere to treatment [31, 32].

A previously cited drawback of at-home, oral medications is that it cannot be confirmed that the medication is being taken by the patient as prescribed. MPR and PDC, which were used to estimate medication adherence, cannot confirm whether medication was taken as prescribed; however, they can provide insights into whether medication was available to the patient. Persistence is another method to understand medication use as it measures the duration of time in which a patient continues the prescribed treatment. Indeed, as both measures of adherence and persistence were high in this study, it indicates the medication was available to a large percentage of patients who continued to take it as prescribed. As such, the high risdiplam adherence and persistence in the present study may lead to lower rates of comorbidities, costs, and healthcare resource utilization [20].

As onasemnogene abeparvovec is a one-time treatment, nusinersen is the only other SMA DMT for which adherence and persistence results have been previously reported (Table 6). Compared with risdiplam, nusinersen had lower adherence and persistence values in prior real-world studies. There is evidence that repeated intrathecal injections and dosing schedule management has negative impacts on the adherence to and persistence with nusinersen [21, 33, 34]. These impacts may be more pronounced during the loading dose phase when dosing is the most frequent [33]. Some patients have expressed fear and anxiety of the intrathecal procedures, which reduces overall treatment satisfaction and may be another reason for lower adherence with nusinersen. One observational study found patients receiving nusinersen preferred to switch to risdiplam because of pain or anxiety attributed to the intrathecal procedure despite the increased dosing frequency of risdiplam [29]. In addition, for patients receiving nusinersen, regular doses must be received through intrathecal administration at specialized treatment centers. These treatment facilities are often located far from a patient’s home, which can cause delays in treatment due to increased economic burden associated with travelling, work leave, and healthcare resource utilization [35, 36].

The differences observed between nusinersen and risdiplam in adherence and persistence may also be related to different study methodologies, including how adherence and persistence were defined, datasets used, number of individuals included, and length of follow-up. As a result of the nature of the dosing administration of nusinersen, adherence can be calculated at the patient level [21], dose level [22], or both [20]. Patient-level adherence considers the adherence of each individual within the study population to estimate a population’s overall adherence. Dose-level adherence records all doses received for each individual in the study population to provide estimates on the number of doses that were received on time. Dose-level adherence could be highly influenced by a small number of patients contributing more doses within the analysis [37]. For example, analyses of nusinersen adherence at the dose level (e.g., Youn et al.) [22] have reported higher levels of adherence to nusinersen than studies analyzing adherence at the patient level (e.g., Fox et al.) [21]. Differences in adherence at the dose level (e.g., 72–76%) versus at the patient level (e.g., 27–44%) are apparent even within the same study [20]. The present study assessed patient-level adherence using prescription fills.

In addition, Elman et al. [38] reported adherence and persistence data from nine SMA specialized centers, whereas Gauthier-Loiselle et al. [20] and Fox et al. [21] made use of nationally representative claims databases. Specialized treatment centers such as those reported by Elman et al. may report higher rates of medication adherence and persistence, as they have a higher concentration of resources and individuals with expertise in a specific disease area [22, 33].

A strength of this study is that the data analyzed originated from a specialty pharmacy that included ≥ 98% of the dispensing information on risdiplam in the USA. Using this specialty pharmacy is advantageous because it is independent of insurance coverage claims and relies on prescription fill information. Therefore, individuals who switched insurance or were uninsured and made self-pay cash payments were included in this study as long as they received ≥2 fills of risdiplam within a 12-month period. Despite SMA being a rare disease, the sample size from this study is quite large (N = 1636) compared with other studies of SMA DMTs, meaning the results are representative of individuals with SMA in the USA treated with risdiplam.

This study has some limitations. Reasons for gaps in risdiplam refills cannot be determined with claims data alone. The gaps in risdiplam refills observed could be due to patient-related or insurance-related (e.g., denial of reapproval for treatment) reasons. Certain patient-related factors are not captured in claims data, such as socioeconomic factors and patient and provider preferences, which may influence treatment adherence and persistence [39]. Patients with a higher socioeconomic status and those with better healthcare access (e.g., more advanced health literacy and more in-depth insurance coverage) are more likely to remain adherent to medication [40–42]. Additionally, the level of disease severity could affect adherence and persistence to medication [43]. In the present study, patient socioeconomic status, education level, or characteristics of disease severity such as SMA type or SMN2 copy number were not available. As with all claims-based studies, data may be subject to measurement error due to miscoding. Approximately 14% of individuals (n = 234) included in the analyses did not have a recorded age, which may have impacted the analyses of adherence and persistence by age. Although this specialty pharmacy reports ≥ 98% of all risdiplam dispensing information in the USA, dispensing information for patients receiving risdiplam through the free drug program or through third parties was not captured, which may have impacted adherence and/or persistence results Lastly, the study period was 12 months; an increased follow-up time is needed to understand long-term adherence and persistence.

Conclusion

This study determined that over a 12-month period, adherence to and persistence with risdiplam were high among patients with SMA, regardless of age and payer type. Potential topics of interest for the future include a direct comparison of adherence and persistence with other SMA DMTs using a single dataset, analyzing factors that impact risdiplam-specific adherence and persistence, and understanding any gaps in supply and treatment discontinuation. Determining the impact of non-adherence and non-persistence on SMA-related comorbidities, healthcare resource utilization, and costs may be useful to further understand the SMA DMT landscape.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available because our study used deidentified data that are proprietary to a third-party data vendor, and thus these data cannot be made available to readers.

References

Darras BT. Spinal muscular atrophies. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2015;62(3):743–66.

Kolb SJ, Kissel JT. Spinal muscular atrophy. Neurol Clin. 2015;33(4):831–46.

Lefebvre S, Bürglen L, Reboullet S, et al. Identification and characterization of a spinal muscular atrophy-determining gene. Cell. 1995;80(1):155–65.

Prior TW, Leach ME, Finanger E. Spinal muscular atrophy. In: Adam MP, et al., editors. GeneReviews®. Seattle, WA: University of Washington; 1993.

Biogen Inc. SPINRAZA® (nusinersen) US prescribing information. December 2016. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2016/209531lbl.pdf. Accessed Apr 2024.

Novartis Gene Therapies, Inc. ZOLGENSMA® (onasemnogene abeparvovec-xioi) US prescribing information. December 2023. https://www.novartis.com/us-en/sites/novartis_us/files/zolgensma.pdf. Accessed Apr 2024.

US Food and Drug Administration. EVRYSDI™ highlights of prescribing information. 2020. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2020/213535s000lbl.pdf. Accessed Apr 2024.

Cure SMA. FDA approves Genentech’s Evrysdi (risdiplam) for use in babies under two months with spinal muscular atrophy. 2022. https://www.curesma.org/fda-approves-genentechs-evrysdi-risdiplam-for-use-in-babies-under-two-months-with-spinal-muscular-atrophy/. Accessed Apr 2024.

Schorling DC, Pechmann A, Kirschner J. Advances in treatment of spinal muscular atrophy—new phenotypes, new challenges, new implications for care. J Neuromuscul Dis. 2020;7(1):1–13.

Mercuri E, Finkel RS, Muntoni F, et al. Diagnosis and management of spinal muscular atrophy: part 1: recommendations for diagnosis, rehabilitation, orthopedic and nutritional care. Neuromuscul Disord. 2018;28(2):103–15.

Sumner CJ, Crawford TO. Early treatment is a lifeline for infants with SMA. Nat Med. 2022;28(7):1348–9.

Masson R, Mazurkiewicz-Beldzinska M, Rose K, et al. Safety and efficacy of risdiplam in patients with type 1 spinal muscular atrophy (FIREFISH part 2): secondary analyses from an open-label trial. Lancet Neurol. 2022;21(12):1110–9.

Finkel RS, Mercuri E, Darras BT, et al. Nusinersen versus sham control in infantile-onset spinal muscular atrophy. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(18):1723–32.

Day JW, Finkel RS, Chiriboga CA, et al. Onasemnogene abeparvovec gene therapy for symptomatic infantile-onset spinal muscular atrophy in patients with two copies of SMN2 (STR1VE): an open-label, single-arm, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet Neurol. 2021;20(4):284–93.

Łusakowska A, Wójcik A, Frączek A, et al. Long-term nusinersen treatment across a wide spectrum of spinal muscular atrophy severity: a real-world experience. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2023;18(1):230.

Ñungo Garzón NC, Pitarch Castellano I, Sevilla T, Vázquez-Costa JF. Risdiplam in non-sitter patients aged 16 years and older with 5q spinal muscular atrophy. Muscle Nerve. 2023;67(5):407–11.

Sitas B, Hancevic M, Bilic K, Bilic H, Bilic E. Risdiplam real world data—looking beyond motor neurons and motor function measures. J Neuromuscular Dis. 2023;11:75–84.

Kakazu J, Walker NL, Babin KC, et al. Risdiplam for the use of spinal muscular atrophy. Orthop Rev (Pavia). 2021;13(2):25579.

Weaver MS, Yuroff A, Sund S, Hetzel S, Halanski MA. Quality of life outcomes according to differential nusinersen exposure in pediatric spinal muscular atrophy. Children (Basel). 2021;8(7):604.

Gauthier-Loiselle M, Cloutier M, Toro W, et al. Nusinersen for spinal muscular atrophy in the United States: findings from a retrospective claims database analysis. Adv Ther. 2021;38(12):5809–28.

Fox D, To TM, Seetasith A, Patel AM, Iannaccone ST. Adherence and persistence to nusinersen for spinal muscular atrophy: a US claims-based analysis. Adv Ther. 2022;40(3):903–19.

Youn B, Proud CM, Wang N, et al. Examining real-world adherence to nusinersen for the treatment of spinal muscular atrophy using two large US data sources. Adv Ther. 2023;40(3):1129–40.

Droege M, Sproule D, Arjunji R, Gauthier-Loiselle M, Cloutier M, Dabbous O. Economic burden of spinal muscular atrophy in the United States: a contemporary assessment. J Med Econ. 2020;23(1):70–9.

Monette A, Chen E, Bazzano A, Dixon S, David Arnold W, Shi L. Treatment preference among patients with spinal muscular atrophy (SMA): a discrete choice experiment. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2021;16:36.

Canfield SL, Zuckerman A, Anguiano RH, et al. Navigating the Wild West of medication adherence reporting in specialty pharmacy. J Manage Care Spec Pharm. 2019;25(10):1073–7.

Engmann NJ, Sheinson D, Bawa K, Ng CD, Pardo G. Persistence and adherence to ocrelizumab compared with other disease-modifying therapies for multiple sclerosis in U.S. commercial claims data. J Manage Care Spec Pharm. 2021;27(5):639–49.

Pardo G, Pineda ED, Ng CD, Bawa KK, Sheinson D, Bonine NG. Adherence to and persistence with disease-modifying therapies for multiple sclerosis over 24 months: a retrospective claims analysis. Neurol Ther. 2022;11(1):337–51.

Kozma CM, Dickson M, Phillips AL, Meletiche DM. Medication possession ratio: implications of using fixed and variable observation periods in assessing adherence with disease-modifying drugs in patients with multiple sclerosis. Patient Prefer Adher. 2013;7:509–16.

Powell JC, Meiling JB, Cartwright MS. A case series evaluating patient perceptions after switching from nusinersen to risdiplam for spinal muscular atrophy. Muscle Nerve. 2023;69(2):179–84.

**ao L, Kang S, Djordjevic D, et al. Understanding caregiver experiences with disease-modifying therapies for spinal muscular atrophy: a qualitative study. Arch Dis Child. 2023;108(11):929–34.

Gusset N, Stalens C, Stumpe E, et al. Understanding European patient expectations towards current therapeutic development in spinal muscular atrophy. Neuromuscul Disord. 2021;31(5):419–30.

Wan HWY, Carey KA, D'Silva A, Kasparian NA, Farrar MA. “Getting ready for the adult world”: how adults with spinal muscular atrophy perceive and experience healthcare, transition and well-being. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2019;14(1):74.

Michelson D, Ciafaloni E, Ashwal S, et al. Evidence in focus: Nusinersen use in spinal muscular atrophy: report of the guideline development, dissemination, and implementation subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2018;91(20):923–33.

Zingariello CD, Brandsema J, Drum E, et al. A multidisciplinary approach to dosing nusinersen for spinal muscular atrophy. Neurol Clin Pract. 2019;9(5):424–32.

Chen E, Dixon S, Naik R, et al. Early experiences of nusinersen for the treatment of spinal muscular atrophy: results from a large survey of patients and caregivers. Muscle Nerve. 2021;63(3):311–9.

Cordts I, Lingor P, Friedrich B, et al. Intrathecal nusinersen administration in adult spinal muscular atrophy patients with complex spinal anatomy. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2020;13:1756286419887616.

Vrijens B, De Geest S, Hughes DA, et al. A new taxonomy for describing and defining adherence to medications. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;73(5):691–705.

Elman L, Youn B, Proud CM, et al. Real-world adherence to nusinersen in adults with spinal muscular atrophy in the US: a multi-site chart review study. J Neuromuscul Dis. 2022;9(5):655–60.

Lam, WY, Fresco, P. Medication Adherence Measures: An Overview. Biomed Res Int, 2015. 2015: p. 217047

Wilder ME, Kulie P, Jensen C, et al. The impact of social determinants of health on medication adherence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36(5):1359–70.

Osterberg L, Blaschke T. Adherence to medication. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(5):487–97.

Osborn CY, Kripalani S, Goggins KM, Wallston KA. Financial strain is associated with medication nonadherence and worse self-rated health among cardiovascular patients. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2017;28(1):499–513.

DiMatteo MR, Haskard KB, Williams SL. Health beliefs, disease severity, and patient adherence: a meta-analysis. Med Care. 2007;45(6):521–8.

Medical Writing, Editorial, and Other Assistance

Medical writing assistance for this manuscript was provided by Kathryn Russo, PhD, of Nucleus Global. Editing assistance was provided by Lee Ann Pastorello of Nucleus Global. Support for this assistance was funded by F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd, Basel, Switzerland, in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP 2022) guidelines (http://www.ismpp.org/gpp-2022).

Funding

Sponsorship for this study, including the journal’s Rapid Service and Open Access fees, was funded by Genentech Inc, South San Francisco, CA, USA.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Elmor D. Pineda, Tu My To, Travis Dickendesher, Sheila Shapouri, and Susan T. Iannaccone contributed to the conception and design, material preparation, data collection, and writing. All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interests

Elmor D. Pineda, Tu My To, Travis Dickendesher, and Sheila Shapouri are employees of Genentech Inc and shareholders of F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd. Susan T. Iannaccone has received funding from the National Institutes of Health, Muscular Dystrophy Association, Parent Project Muscular Dystrophy, Cure SMA, Department of Defense, Ave**s, Biogen, PTC Therapeutics, Sarepta, FibroGen, Pfizer and ScholarRock.

Ethical Approval

The present study made use of deidentified data and was thus exempt from the institutional review board review. This research was compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. Genentech, Inc, has a data use agreement with the specialty pharmacy utilized in this study, which allows Genentech-associated researchers to use and analyze their data and to publish the corresponding results.

Additional information

Prior Presentation: A subset of results presented in this manuscript were presented at the International TREAT-NMD Conference, December 7–9, 2022, the Muscular Dystrophy Association Clinical and Scientific Conference March 19–22, 2023, and the Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy Annual Meeting, March 21–24, 2023.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pineda, E.D., To, T.M., Dickendesher, T.L. et al. Adherence and Persistence Among Risdiplam-Treated Individuals with Spinal Muscular Atrophy: A Retrospective Claims Analysis. Adv Ther 41, 2446–2459 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-024-02850-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-024-02850-9