Abstract

Chronic inflammation induced by infection, autoimmune disorders, and immune reaction against foreign bodies are recognized as causative factors for the development of lymphoma. Here, a case of B cell lymphoma arising after augmentation rhinoplasty with filler injection is reported. A 48-year-old Japanese woman underwent rhinoplasty with filler injection at a cosmetic clinic 10 years ago. She, presently, came with complaints of a nodule at the nasal root. Histologic examination of the biopsy specimen revealed diffuse infiltration of centrocyte-like cells with plasmacytic differentiation in the subcutis and procerus muscle. Immunohistochemistry showed that the tumor cells were CD3−, CD5−, CD10−, CD20+, CD79+, bcl-2+, bcl-10+, IgG+, IgA−, and IgM−. In situ hybridization for Epstein-Barr virus small RNAs was negative. The final diagnosis was extranodal marginal zone lymphoma. This is a case of foreign body-induced carcinogenesis. Various aspects of chronic inflammation that propel lymphoma development are discussed with their morphology, immunophenotype, and viral association.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

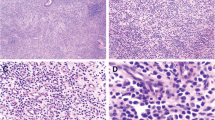

Chronic inflammation is an important etiological factor of lymphomagenesis. The prototype of lymphoma associated with chronic inflammation is pyothorax-associated lymphoma (PAL), which was described by Aozasa et al. in 1987 [1]. Diffuse large B cell lymphoma associated with chronic inflammation (DLBCL-CI), enlisted in the revised fourth edition of the WHO Classification of Tumors of Hematopoietic and Lymphoid tissues (2017), is nearly synonymous with PAL [2]. Extranodal marginal zone lymphoma (EMZL) arising from chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis (Hashimoto’s disease), an organ-specific autoimmune disease, and chronic gastritis caused by Helicobacter pylori are other example of lymphomas associated with chronic inflammation. PAL is Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) positive, whereas EMZL is negative, except for unusual cases under immunosuppression or immune dysfunction [ A 48-year-old Japanese woman noticed swelling in the nasal bridge with no B symptoms 1 month before admission. She had undergone augmentation rhinoplasty with filler injection in the nasal root at a cosmetic clinic more than 10 years ago. Physical examination and imaging studies using PET/CT and MRI revealed a nodular lesion approximately 1 cm in diameter in the left nasal root, which showed accumulation of 2-[18F]-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose (SUVmax = 6.7) (Fig. 1). There was no lymphadenopathy in the head and neck region, thorax, or abdomen. Blood tests showed mild anemia and thrombocytosis. Serum lactate dehydrogenase levels were slightly elevated (254UI/L). The anti-human immunodeficiency virus antibody level was not elevated. Histopathological examination of a biopsy specimen from the nasal subcutaneous tumor revealed cutaneous EMZL. After definitive diagnosis, she was admitted to another hospital for systemic work-up and received 6 courses of chemotherapy with rituximab, pirarubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisolone according to her request to avoid facial surgery. She was survived without recurrence 5 months after diagnosis. Biopsied tissues were routinely formalin-fixed and embedded in paraffin. Histological sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Immunohistochemical staining was performed using the paraffin-embedded sections with BOND-III fully automated IHC and ISH system (Leica Biosystems, Nussloch, Germany). The panel of primary antibodies used included CD3 (clone PS1) (Nichirei Biosciences, Tokyo, Japan), CD5 (clone 4C7) (Leica Biosystems), CD10 (clone 56C6) (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA), CD20 (clone L26) (Nichirei Biosciences), CD79 (clone JCB117) (Nichirei Biosciences), bcl-2 (clone 124) (Agilent), bcl-10 (clone 151) (Agilent), IgG (clone A57H) (Nichirei Biosciences), IgA (polyclonal), and IgM (clone R1/69) (Nichirei Biosciences). In situ hybridization (ISH) for EBV-encoded small RNA (EBER) and fluorescent ISH for using a break-apart probe for MALT1 (Leica Biosystems) was performed using the same system supplied by Leica Biosystems. Gene rearrangement studies for IGH, IGK, and IGL were performed using BIOMED-2 multiplex PCR-based methods with DNA extracted from paraffin-embedded tumor tissues. Histological examination of a biopsy specimen revealed diffuse infiltration of small lymphoid cells in the subcutaneous tissue and procerus muscle (Fig. 2a). Most lymphoid cells had centrocyte-like appearance, a small nucleus with a slightly irregular contour, and inconspicuous nucleoli (Fig. 2b). Some of them showed plasmacytic differentiation. Granulomatous change against the foreign body was not observed in the specimen. Mitotic figures were not discernible. Immunohistochemically, they showed the following results: CD3−, CD5−, CD10−, CD20+, CD79+, bcl-2+, bcl-10+, IgG+, IgA−, and IgM− (Fig. 2c and d). The Ki-67 labeling index was low (< 10%) (Fig. 2e). ISH for EBER was negative. Fluorescent ISH using a break-apart probe did not reveal a translocation involving MALT1. Although gene rearrangement studies for IGH, IGK, and IGL were performed using PCR-based methods with DNA extracted from paraffin-embedded tumor tissues, significant data were not obtained because of DNA degeneration. Histological and immunohistochemical findings. Diffuse infiltration of small lymphoid cells in subcutaneous tissue and procerus muscle was observed (a) (hematoxylin and eosin staining (HE), original magnification × 20). Small lymphoid cells with centrocyte-like appearance monotonously infiltrated among muscular fibers (b) (HE, × 400). Immunohistochemistry showed that tumor cells were CD20-positive (c) and CD10-negative (d), with low Ki-67 labeling index (e) (× 400) Extranodal lymphoma, comprising 24–48% of all non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas, occasionally develops in association with foreign bodies. A representative example is breast implant-associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma (BIA-ALCL); it usually presents with an accumulation of serous fluid (so-called seroma) around a silicone implant placed for reconstruction after mastectomy or purely cosmetic purposes [6, 7]. Neoplastic cells of BIA-ALCL are similar to those of systemic ALCL; these cells exhibit a T-/null-cell phenotype and are CD30-positive, and EBV-negative, although they are usually embedded non-cohesively in seroma and/or adherent to capsular lumen without forming a tumorous mass, with the exception of a minor subset (~ 30%) of the cases showing a mass. Another major example of a foreign body-associated lymphoma is metallic implant-associated lymphoma (MIAL), which develops in association with metallic prosthesis placed in orthopedic procedures [8]. Most MIALs are histologically DLBCLs. Two previously reported cases in which patients were examined based on ISH and/or PCR revealed EBV positivity. MIALs, usually presenting without tumorous masses like BIA-ALCLs, are incidentally found during prosthesis replacement. The average latency between implantation and diagnosis in BLA-ALCL and MIAL ranges from 8 to 11 years [6,7,8]. Lymphoma development related to various medical implants or devices such as cardiac pacemakers, defibrillators, valvular prostheses, grafts, subcutaneous venous access ports, surgical mesh implants, and intraocular silicone have also been reported [5]. Most of these implant-associated lymphomas are DLBCLs and are often EBV-positive. To date, lymphoma development after filler injection into extramammary dermal or subcutaneous tissues for cosmetic purposes has rarely been reported. Lee et al. reported a EMZL 50 years after dermal filler injection (filler material unknown) [9]. Their and our cases share similar clinicopathological characteristics, such as EBV-negativity, EMZL histology, a long latency period, association with dermal filler injection in the face, and favorable prognosis. Previous reports described rare cases of EMZLs that arose after paraffin injection for cosmetic purposes or vaccine inoculation and large B cell lymphoma that developed from pseudolymphoma formed in response to tattoo dye, given the unknown EBV status in these cases [10,11,12]. It seems that these cases and our case differ from BIA-ALCL and MIAL in both biological characteristics and clinical settings. Lymphoma associated with foreign bodies could be subsumed under lymphomas associated with chronic inflammation (Table 1). The prototype of lymphoma develo** in chronic inflammation is PAL, which is a B cell lymphoma develo** in the pleural cavity affected by long-standing pyothorax after artificial pneumothorax for the treatment of tuberculosis or tuberculous pleuritis [1]. Lymphomas associated with chronic osteomyelitis and minute lymphomatous lesions associated with pseudocysts and hydrocele incidentally diagnosed based on histological sections have also been reported [13]. These types of lymphomas share several features: (i) chronic inflammatory background, (ii) long latency period until diagnosis, (iii) occurrence in an enclosed cavity, (iv) DLBCL histology, and (v) EBV-positivity. In the revised 4th edition of the WHO classification of Tumors of Hematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues (2017), these lymphomas are categorized as DLBCL-CI and fibrin-associated DLBCL [2]. Most lymphomas associated with chronic inflammation are B cell lymphomas. This could be partly explained by the hypothesis that persistent antigenic stimulation of lymphocytes by foreign bodies and infectious pathogens underlies oncogenesis driven by chronic inflammation. Antigenic stimulation provides an advantageous environment for selective expansion of B cell clones and subsequent development of B cell neoplasms. Additionally, regarding the relationship between EBV and B cell lymphomagenesis in chronic inflammation, it is interesting to note that EMZLs are largely EBV-negative with the exception of EBV-positive cases under immunosuppression or immune dysfunction, while DLBCLs are usually EBV-positive. Primary gastric and thyroid DLBCLs often arise from antecedent EMZL through transformation, and almost all cases are EBV-negative. This suggests that most cases of EBV-positive DLBCL associated with chronic inflammation may not be related to EMZL and there may be a significant difference in oncogenesis between these two types of lymphoma, although some reports suggest that EBV infection might induce transformation from EMZL to DLBCL [14, 15]. We present a rare case of cutaneous EMZL arising after filler injection. Our case supports the hypothesis that chronic inflammation due to persistent antigen stimulation by foreign body implantation could play a pivotal role in malignant lymphoma development. Our case and previously reported cases of lymphoma associated with chronic inflammation show that this disease concept includes diseases with variable clinicopathological characteristics and oncogenesis, such as BIA-ALCL, EBV-positive DLBCL, and EMZL.Clinical history

Materials and methods

Results

Discussion

References

Iuchi K, Ichimiya A, Akashi A, Mizuta T, Lee YE, Tada H, Mori T, Sawamura K, Lee YS, Furuse K, Yamamoto S, Aozasa K (1987) Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma of the pleural cavity develo** from long-standing pyothorax. Cancer 60:1771–1775

Chan JKC, Aozasa K, Gaulard P (2017) Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma associated with chronic inflammation. In: Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Pileri SA, Stein H, Thiele J, Arber DA, Hasserjian RP, Le Beau MM, Orazi A, Siebert R (ed) WHO classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues, revised 4th edn. IARC, Lyon, pp. 309–311

Gong S, Crane GM, McCall CM, **ao W, Ganapathi KA, Cuka N, Davies-Hill T, ** L, Raffeld M, Pittaluga S, Duffield AS, Jaffe ES (2018) Expanding the spectrum of EBV-positive marginal zone lymphomas: a lesion associated with diverse immunodeficiency settings. Am J Surg Pathol 42:1306–1316

Gibson SE, Swerdlow SH, Craig FE, Surti U, Cook JR, Nalesnik MA, Lowe C, Wood KM, Bacon CM (2011) EBV-positive extranodal marginal zone lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue in the posttransplant setting: a distinct type of posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder? Am J Surg Pathol 35:807–815

Bizjak M, Selmi C, Praprotnik S, Bruck O, Perricone C, Ehrenfeld M, Shoenfeld Y (2015) Silicone implants and lymphoma: the role of inflammation. J Autoimmun 65:64–73

Jones JL, Hanby AM, Wells C, Calaminici M, Johnson L, Turton P, Deb R, Provenzano E, Shaaban A, Ellis IO, Pinder SE, National Co-ordinating Committee of Breast Pathology (2019) Breast implant-associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma (BIA-ALCL): an overview of presentation and pathogenesis and guidelines for pathological diagnosis and management. Histopathology 75:787–796

Rastogi P, Riordan E, Moon D, Deva AK (2019) Theories of etiopathogenesis of breast implant-associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma. Plast Reconstr Surg 143:23S–29S

Sanchez-Gonzalez B, Garcia M, Montserrat F, Sanchez M, Angona A, Solano A, Salar A (2013) Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma associated with chronic inflammation in metallic implant. J Clin Oncol 31:e148–e151

Lee SH, Kim HC, Kim YJ (2017) B-cell lymphoma in a patient with a history of foreign body injection. J Craniofac Surg 28:504–505

Cha JA, Kim B, Lee KA (2017) B cell lymphoma underlying paraffinoma of glabella. J Craniofac Surg 28:798–800

May SA, Netto G, Domiati-Saad R, Kasper C (2005) Cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasia and marginal zone B-cell lymphoma following vaccination. J Am Acad Dermatol 53:512–516

Sangueza OP, Yadav S, White CR Jr, Braziel RM (1992) Evolution of B-cell lymphoma from pseudolymphoma. A multidisciplinary approach using histology, immunohistochemistry, and southern blot analysis. Am J Dermatopathol 14:408–413

Boroumand N, Ly TL, Sonstein J, Medeiros JF (2012) Microscopic diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) occurring in pseudocysts: do these tumors belong to the category of DLBCL associated with chronic inflammation? Am J Surg Pathol 36:1074–1080

Camacho Castañeda FI, Dotor A, Manso R, Martín P, Prieto Pareja E, Palomo Esteban T, García Vela JA, Santonja C, Piris MA, Rodríguez Pinilla SM (2020) Epstein-Barr virus-associated large B-cell lymphoma transformation in marginal zone B-cell lymphoma: a series of four cases. Histopathology 77:112–122

Tao J, Kahn L (2000) Epstein-Barr virus-associated high-grade B-cell lymphoma of mucosal-associated lymphoid tissue in a 9-year-old boy. Arch Pathol Lab Med 124:1520–1524

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Dr. Katsuyuki Aozasa (Emeritus Professor, Osaka University) for useful discussions and would like to thank Mr. Shinya Sasaki and Mr. Masaharu Kohara for their technical assistance with fluorescence ISH and gene rearrangement analysis. The authors would like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The report was designed and written by SN and reviewed by all authors. MK and HK contributed to the clinical data collection. The manuscript was approved by all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Statement of ethics

The patient provided written informed consent for publication.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nakatsuka, Si., Kadowaki, M. & Kaneko, H. Cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma of the nose arising after rhinoplasty with filler injection. J Hematopathol 14, 177–181 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12308-021-00441-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12308-021-00441-z