Abstract

The market equilibrium that is generated in the presence of both price collusion and free entry is analyzed taking under consideration the case of a homogeneous product and the case of differentiated products. The outcomes of this market regime are compared with those of other regimes, including competition (or monopolistic competition), monopoly, fixed price with collusive entry limitation. Some welfare implications of the market regime of price collusion with free entry are examined, with respect to the maximum social welfare allocation and the allocations of other market regimes, so to highlight the inefficiency of price collusion with free entry. The number of producers results to be the maximum number of firms that can produce without incurring into losses. Therefore, social distress is caused by a displacement from the price collusion equilibrium with free entry. Its defence can thus be considered in reference to the desirability of social goals that are in contradiction with economic efficiency.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

See, for instance, Motta (2004) on collusion, in particular where entry is discussed with respect to a monopolistic or oligopolistic situation. Entry in the case of the Cournot oligopoly is particularly examined by Eaton and Ware (1987). With reference to tacit collusion in oligopoly, McLeod et al. (1987) examine the sustainability of collusion even with free entry, by introducing an entry-deterring collusive equilibrium, in which profits are positive. They take into account a competitive market with spatially differentiated products (Löschian competition), where, the number of producers is determined in the first stage under the condition of the Bertrand-Nash equilibrium. The price is determined by collusion in the second stage, so leading to positive profits. Incumbents can deter new entrants by switching to the Bertrand-Nash price.

Pareto often refers to “competition” only in terms of free entry, while current analyses refer to it in terms of price-taking behavior (see, for instance, Debreu 1959) and Walras refers to it both in terms of price-taking and free entry (on this aspects, Montesano 1991). Price collusion makes competition (free entry), “parasitic”, since free entry determines the stealing of consumers rather than the lowering of prices, so generating a severe inefficiency for productions with a fix-cost. Paretian parasitic competition has been forgotten in the economic literature: it is revisited and commented by Zanni in Pareto (1906, 2006), pp. 620–625.

The term corporation indicates in this paper that kind of association of producers which can fix some conditions of production, like the number of producers and/or their selling price.

On collusion, see, for instance, Feuerstein (2005). Brander and Spencer (1985) introduce an analysis which deals with the presence of both collusion and free entry. They consider the case of tacit collusion and base their model on conjectural variation (which is a generalization of Cournot model). However, as the authors specify, “the use of conjectural variation parameter to reflect collusion is a useful but not uncontroversial simplification”. Brander and Spencer aim to model how an equilibrium of tacit collusion can emerge with free entry, and introduce, with this goal in mind, the controversial conjectural variation.

The inefficiency of free entry is examined by Mankiw and Whinston (1986).

The use of the social welfare function in a partial equilibrium analysis could seem unnecessary since the surplus function can be justified in a simpler way following the Marshallian approach. However, taking into account in particular the case with differentiated products which is examined in Sect. 6, I believe that the reference to the social welfare function may be useful to the reader in order to have a rigorous foundation for the surplus function. In any case, the approach followed here is similar to the approach indicated by Mas-Colell et al. (1995, pp. 325–331) for the partial equilibrium context.

If there is not a solution for the equation MC(q) = AC(q), then the maximum total surplus allocation is not an internal solution.

This result, for which \( n^{PC} > n^{C} \), agrees with the statement (Mankiw and Whinston 1986) that, when the product is homogeneous, free entry generates a number of firms larger than the socially optimal number.

If \( F \in \left( {\beta \left( {\frac{A - \alpha B}{1 + 2\beta B}} \right)^{2} ,\frac{{(A - \alpha B)^{2} }}{4B(1 + \beta B)}} \right) \), then no price-taker firm can obtain a non-negative profit, whereas, assuming \( n = 1 \), a monopolist can gain a positive profit and generate a social surplus: this situation corresponds to a natural monopoly.

Specifically, we find that \( S^{PC} < S^{M} \) if \( \frac{A - \alpha B}{{B\sqrt {\beta F} }} > \frac{2}{\sqrt 3 - 1} = 2.732 \) and \( S^{PC} > S^{M} \) if \( \beta B > \frac{2}{\sqrt 3 } = 1.1547 \) and \( \frac{A - \alpha B}{{B\sqrt {\beta F} }} \in \left( {2\sqrt {\frac{1 + \beta B}{\beta B}} ,_{{}} 2.732} \right) \).

Of course, the price cannot be so high that profit is negative even if only one firm is active.

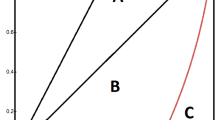

Function \( p^{coll} = \varphi (n) = \arg \mathop {\max }\limits_{p} \left( {\frac{pD(p)}{n} - f\left( {\frac{D(p)}{n}} \right)} \right) \) requires, in this example, \( p^{coll} = \frac{1}{2B}\frac{(A + \alpha B)n + 2\beta AB}{n + \beta B} \), which is a decreasing function with \( \varphi (0) = \frac{A}{B} \) and \( \lim_{n \to \infty } \varphi (n) = \frac{1}{2B}(A + \alpha B) \). Function \( n^{fe} = \psi (p) \) derives from the condition \( p = AC(q) \), where \( q = \frac{D(p)}{n} \). It is \( n^{fe} = \frac{1}{2F}(p - \alpha )(A - Bp)\left( {1 \pm \sqrt {1 - \frac{4\beta F}{{(p - \alpha )^{2} }}} } \right) \) for the case under consideration.

This formulation differs from Spence’s (1976) proposal of a utility function of the type \( G\left( {\sum\nolimits_{i = 1}^{n} {f_{i} (q_{i} )} } \right) \). Spence starts with this assumption on the aggregate utility function and analyzes the case of differentiated products accordingly. In this paper we start from demand functions and derive from them the aggregate utility function.

It is \( p^{PC} < p^{M} \) in the example presented in the following Sect. 7. We can find examples for which \( p^{PC} > p^{M} \). For instance, let us introduce the demand function \( p_{i} = 20 - 3q_{i} - \sum\nolimits_{j = 1,j \ne i}^{n} {q_{j} + \frac{1}{6}} q_{i}^{2} \) for \( q_{i} < 5 \) and the cost function \( c_{i} = 9 + \frac{1}{2}q_{i} \), for every \( i = 1, \ldots ,n \). The monopoly equilibrium requires \( q^{M} = 3 \), \( n^{M} = 2 \), and \( p^{M} = 9.5 \). The equilibrium of price collusion with free entry requires \( q^{PC} = 0.93 \), \( n^{PC} = 8.72 \) and \( p^{PC} = 10.17 \).

It is equivalent to use the direct demand function \( q_{i} = a - bp_{i} + d\sum\nolimits_{j = 1,j \ne i}^{n} {p_{j} } \), with \( d < b \), in place of the above inverse demand function.

Also Mankiw and Whinston (1986), as well as other scholars, indicate that free entry can generate a number of firms larger or smaller than the socially optimal number.

Pareto remarks the importance of considering social factors in economics. He writes (Pareto 1906): “Scientifically, it can be proved that protection usually causes a destruction of wealth. […] But is that sufficient to condemn protection in the concrete case? Certainly not: it is necessary to think about the other social consequences of that regime and to make a decision only after completing this review.”

References

Brander JA, Spencer BJ (1985) Tacit collusion, free entry and welfare. J Ind Econ 33:277–294

Chandler AD Jr (1977) The visible hand. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge

De Robertis FM (1973) Storia delle corporazioni e del regime associativo nel mondo romano, I–II, Adriatica, Bari

Debreu G (1959) Theory of value. Yale University Press, New Haven

Eaton BC, Ware R (1987) A theory of market structure with sequential entry. Rand J Econ 18:1–16

Feuerstein S (2005) Collusion in industrial economics – A survey. J Ind Compet Trade 5:163–198

Giocoli N (2010) Games judges don’t play: predatory pricing and strategic reasoning in US Antitrust. Available at SSRN: htpp://ssrn.com/abstract=1676095

Mankiw NG, Whinston MD (1986) Free entry and social inefficiency. Rand J Econ 17:48–58

Marshall A (1890, 1925) Some aspects of competition. In: Pigou AC (ed) Memorials of Alfred Marshall. Macmillan, London, pp 256–291

Mas-Colell A, Whinston MD, Green JR (1995) Microeconomic theory. Oxford University Press, New York

McLeod WB, Norman G, Thisse J-F (1987) Competition, tacit collusion and free entry. Econ J 97:189–198

Montesano A (1991) L’impresa e la produzione nella teoria dell’equilibrio economico generale. In: Zamagni S (ed) Imprese e mercati. Utet, Torino, pp 31–78

Motta M (2004) Competition policy, theory and practice. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Pareto V (1906, 2006) Manuale di economia politica. In: Montesano A, Zanni A, Bruni L (eds) Critical edition. Università Bocconi Editore, Milano

Spence M (1976) Product selection, fixed costs, and monopolistic competition. Rev Econ Stud 43:217–235

Van Nijf O (1997) The civic world of professional associations in the roman east. J.C. Gieben, Amsterdam

Acknowledgments

I thank Michele Grillo, Michael McLure, Ivan Moscati, Marco Ottaviani, the participants to the Symposium on Economic Theory (Bocconi University, Milan, 6–7 July 2009), and two anonymous referees for their helpful comments and discussions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Montesano, A. Price collusion with free entry: the parasitic competition. Int Rev Econ 59, 41–65 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12232-011-0141-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12232-011-0141-x