Abstract

Parents may develop burnout when they chronically lack the resources to handle parenting stressors. Although the relationship between parental burnout and child-related variables has been explored, its impact on adolescents’ development remains unknown. This study investigates the effect of mothers’ parental burnout on social adaptation and security in adolescents, and the mediating roles of mothers’ parenting styles. Questionnaires were distributed to adolescents and their mothers at three time points with an interval of six weeks. In the first survey, 916 mothers completed a parental burnout assessment. In the second, 1054 adolescents completed maternal rejection and maternal autonomy support scales, and a Harsh Parenting assessment. In the third, 1053 adolescents completed Children and Adolescent Social Adaptation and Security Questionnaires. In total, 411 paired data points were matched (mothers’ age: M = 42.1, SD = 4.65; adolescents’ age: M = 13.1, SD = 0.52). The results of bootstrap** indicated the following: (1) Mothers’ parental burnout negatively predicted adolescents’ social adaptation and security. (2) Mothers’ parenting styles of rejection, harsh parenting, and autonomy support mediated the relationship between parental burnout and social adaptation and security. These findings confirmed the importance of mothers’ influence on adolescents’ parenting activities. Therefore, the enrichment of parenting resources and a decrease in the use of negative parenting styles may promote the healthy psychological development of the children of mothers facing parental burnout.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

With steady worldwide economic and societal development, people are becoming increasingly focused on parenting quality and the development of children. This demands new requirements from parents and increases the difficulties and challenges they face (Mikolajczak & Roskam, 2020). When parents face chronic parenting stress without enough resources, they may develop parental burnout (Roskam et al., 2017), which manifests through four primary symptoms: parents feel exhausted in their parenting role, detach themselves emotionally from their children, do not enjoy being with their children anymore, lose fulfillment in parenting, and do not recognize themselves as the parents they used and want to be (Roskam et al., 2018).

Since Roskam (2017) developed the measurement of parental burnout, this topic has received considerable worldwide attention. Research has shown that parental burnout is associated with factors like socially prescribed perfectionism (Sorkkila & Aunola, 2020; Raudasoja et al., 2022), perfectionistic concerns (Lin et al., 2021; Lin & Szczygieł, 2022; Song et al., 2023), being neurotic or having a lack of emotional or stress management abilities (Le Vigouroux et al., 2017; Roskam et al., 2017), and avoidant attachment (Mikolajczak et al., 2018a). Moreover, interactional factors like a lack of emotional or practical support from a co-parent (Sánchez-Rodríguez et al., 2019) and having children with special needs (Norberg et al., 2014) could also cause parental burnout. However, relatively less attention has been paid to the consequences of parental burnout, with few studies highlighting the seriousness of the consequences of parental burnout. For instance, a prior study found that parental burnout can lead to job burnout (Wang et al., 2022a), depression, anxiety, suicidal ideation, and even to the parent esca** their duties (Mikolajczak et al., 2019). Beyond the parents, it also has consequences for the couple’s relationship, notably by increasing conflicts (Blanchard et al., 2020).

Based on parenting objectives, the parenting activities of burned-out parents will eventually affect the health and growth of their children. Prior studies showed that parental burnout may result in neglectful and violent behavior toward one’s children (Mikolajczak et al., 2018b). In addition, a study found that parental burnout can impact young children by drastically reducing self-control, which could result in problematic behaviors in the future (Wang et al., 2022b). However, only a few studies have directly examined the effects of parental burnout on adolescents’ development (e.g., Chen et al., 2021). As adolescents represent the main force of the future development of any country, their mental health should be one of the most urgent directions of parental burnout research. Thus, this study focuses on the effects of parental burnout on adolescents’ mental health.

Although prior studies explored the impact of parental burnout on adolescents, these focused on a single indicator of adolescent mental health, failing to provide a comprehensive understanding of the impact of parental burnout on adolescents. For example, areas of focus have included adolescents’ phubbing (Zhang et al., 2023), depression, and anxiety (Yang et al., 2021). Based on previous research (An et al., 2004; Nie et al., 2008), this study focuses on adolescents’ social adaptation and security as outcome variables. In this study, social adaptation is viewed as an extrinsic performance indicator and security as an intrinsic perception of adolescents’ psychological development indicators. These may provide a comprehensive and accurate exploration of the negative effects of parental burnout on adolescents. Furthermore, parenting style was selected as a mediating variable for the purposes of this study. A prior study associated parental burnout with specific types of parenting styles (Mikkonen et al., 2022). Following the parenting process model (Belsky, 1984), parental burnout as a negative parental experience may prompt parents to adopt more negative parenting styles and less positive ones, which might negatively affect their children. Therefore, parental burnout may result in parenting behavior changes (Mikkonen et al., 2022), which could affect adolescents’ healthy development (Yang et al., 2021; Chen et al., 2021).

In China, parents are influenced by the traditional family division model that purports that “men work outside while women do the housework at home”. As such, mothers tend to be more involved in daily childcare than fathers (Yu & Wang, 2019; Shu et al., 2016). Therefore, as their primary caregivers, mothers generally have a stronger influence on adolescents (Renk et al., 2003). Furthermore, a study demonstrated that mothers exhibited higher levels of parental burnout (Wang et al., 2022a, 2022b). Similarly, another study indicated that mothers experience more parenting stress than fathers, which renders them more prone to parental burnout (Meeussen & Laar, 2018). Therefore, this study focuses on a sample of mothers.

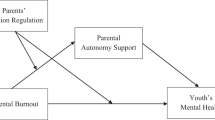

Specifically, the focus of this study is on the effects of mothers’ parental burnout on adolescents’ social adaptation and security, including the mediation effects of mothers’ positive and negative parenting styles in terms of rejection, harsh parenting, and autonomy support.

Parental burnout and adolescents’ social adaptation and security

Adolescence is a critical period in the lives of all human beings. It marks the transition from childhood to adulthood, during which significant physical and psychological changes occur in the body (Das et al., 2016). Social adaptation is the main goal of adolescent socialization and an important indicator of their development (Nie et al., 2008). Regarding socialization, the family plays an essential role in the development of individual social adaptation, as it is the place where most socialization occurs. However, because burned-out parents can only provide basic security to their children, they may be unable to provide their children with enough love and attention (Roskam et al., 2018), thereby hampering these children’s emotional growth. Moreover, burned-out parents tend to ignore children’s needs, leaving them without guidance on how to appropriately deal with problems. Consequently, these children, when approaching adolescence, cannot satisfy their psychological needs, resulting in more negative emotions and lower levels of social adaptation (Nie et al., 2008; Mcdowell & Parke, 2010).

Security is the anticipation of possible dangers or risks and the individual’s sense of power/powerlessness in dealing with them, which is expressed through a sense of certainty and control (An et al., 2004). One study indicated that parent–child conflict and interparental conflict are the main factors affecting adolescents’ security (Allen et al., 2003; Huang et al., 2017). Conflicts between family members could disrupt the family structure and stability, making individuals more sensitive to security and exposing them to a fear of uncertainty. Furthermore, burned-out parents may experience more conflict and estrangement between partners (Mikolajczak et al., 2018b). When adolescents chronically live in an environment that lacks comfort and intimacy over time, the insecurities and tensions that develop in the family may affect their interpersonal interactions and consequently, their life, resulting in reduced security. Therefore, this study explored the negative effects of parental burnout on the psychological development of adolescents using social adaptation as an extrinsic behavior indicator and security as an intrinsic perception of their psychological development. Thus, for this study, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H1a

Parental burnout is negatively related with adolescents’ social adaptation.

H1b

Parenting burnout is negatively related with adolescents’ security.

Parenting styles and adolescents’ social adaptation and security

Across parent–adolescent interaction settings, it has been noted that parenting style has an effect on adolescents’ behavior and outcomes (Darling & Steinberg, 1993), which is expressed through externalizing performance (e.g., social adaptation) and internalizing psychological states (e.g., security). First, it has been found that adolescents’ social adaptation varies according to parenting styles. For instance, a study authoritative parenting with children’s social adaptation, whereas authoritarian and permissive parenting were negatively associated with children’s social adaptation (Zhang et al., 2021).

Second, it has been found that parenting styles are strongly associated with adolescents’ security. For instance, research revealed that negative parenting styles affect the parent–child relationships, which may further affect children’s security (Li et al., 2022). Furthermore, existing research reported that parental love can make children feel a sense of security and reduce loneliness (Gunarsa, 2008). Many prior studies explored the impact of parenting on adolescents’ psychological conditions, investigating both the positive (e.g., autonomy support) and negative (e.g., rejection, harsh parenting) aspects of parenting styles (Bernier et al., 2010; Chang et al., 2003; Zou et al., 2021). However, the influence of parenting style on adolescent development could be investigated more comprehensively by simultaneously focusing on both negative and positive aspects. Therefore, the current study used harsh parenting and rejection as indicators of negative parenting styles, and autonomy support as indicators of positive parenting styles to assess the effects of these different styles on adolescents’ mental health. Thus, the following two hypotheses are proposed:

H2a

Harsh parenting and rejection are negatively related to social adaptation, whereas autonomy support is positively related to it.

H2b

Harsh parenting and rejection are negatively related to security, whereas autonomy support is positively related to security.

Mediation effects of parenting styles

As the parenting process model (Belsky, 1984) posits, parenting styles are influenced by parental experience. Specifically, parents with positive parental experiences may consider themselves good parents and adopt positive parenting styles such as autonomy support and emotional warmth (e.g., Jones & Prinz, 2005). However, when they feel bound by their parenting role, they may adopt negative parenting styles such as excessive rejection, harsh punishment, or even violence (e.g., Shea & Coyne, 2011). Parental burnout as a negative parental experience may increase parent–child conflict or couple conflict and disrupt the family environment (Mikolajczak et al., 2018b), which will likely prompt parents to adopt more negative parenting styles and less positive ones.

Furthermore, as one of the most fundamental family environment factors affecting adolescents’ development, parenting style plays an essential role in their developmental process. This, in turn, affects adolescents’ social adaptation and security (Gunarsa, 2008; Li et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2021). Thus, this study investigates the mediating role of different parenting styles in the relationship between parental burnout and adolescents’ social adaptation and security. To this end, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H3a

The relationship between parental burnout and social adaptation is mediated by parenting styles.

H3b

The relationship between parental burnout and security is mediated by parenting styles.

The framework of this study is shown in Fig. 1.

Methods

Participants

The participants in this study were 411 pairs of middle school students and their mothers in Henan Province, China. The average age of the mothers was 42.1 years (SD = 4.65) and that of the adolescents was 13.1 years (SD = 0.52). There were 204 girls (49.6%) and 207 boys (50.4%). We applied G*power to calculate the minimum sample size required for the hypothesized model. The effect size f2 was set at 0.15, the significance level (α) at 0.05, power at 0.95, and the number of total predictors at 4. The results showed that 129 samples were required to validate the hypotheses of this study, confirming that the 411 samples included in our study were adequate for the analysis.

Procedure

This study used multi-data sources and multi-time points to control for common method bias (Podsakoff et al., 2003; Siemsen et al., 2010). Based on operational definitions of the variables and screening of the questionnaires with good reliability and validity, the measurement of parental burnout was more frequently reported by parents (e.g., Wang et al., 2023), while information on parenting styles (e.g., Liu & Wang, 2021), adolescents’ social adaptation (e.g., Yin et al., 2021) and security (e.g., Shao et al., 2021) were more frequently reported by adolescents. Therefore, the participants were asked to complete three surveys with a six-week time lag between each measurement point in this study. In the first survey, a quick response (QR) code was sent to middle school teachers, which was linked to a questionnaire. The teachers then sent the QR link to the students’ mothers so that they could fill it out. The second and third surveys were completed by students in the classroom.

Adolescents and their mothers were asked to provide the last four digits of their mothers’ phone numbers, which were used to match the three rounds of questionnaire data. In the first round of data collection, 916 mothers completed the Parental Burnout Assessment. In the second round, 1054 adolescents completed the Maternal Rejection Scale, Maternal Autonomy Support Scale, and Harsh Parenting Assessment. In the third round, 1053 adolescents completed the Children and Adolescent Social Adaptation Questionnaire and the Security Questionnaire. In total, 411 paired data points were matched. The attrition rate was 55.1% from the first to third round. The main reasons for sample attrition were the presence of missing data and inconsistent coding across the three rounds.

All participants provided their written informed consent. They were informed that the purpose of the survey was to determine family relationships, and that participation was voluntary. Furthermore, they were assured that there were no repercussions if they did not participate in the survey. The participants were also informed that they could stop responding at any time. Finally, this study was approved by the research ethics committee of the authors’ academic institution.

Measures

Parental burnout

Parental burnout was assessed using the Chinese version of the Parental Burnout Assessment (Wang et al., 2021). It comprises seven items, and each item is rated on a seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (completely inconsistent) to 7 (completely consistent), with a higher score representing higher burnout. [An example item is: “I feel as though I have lost my direction as a mom.”] In this study, the Cronbach’s α was 0.89.

Rejection

Rejection was assessed using the rejection subscale of the Chinese version of the short-form Egna Minnen av Barndoms Uppfostran (Arrindell et al., 1983; Jiang et al., 2010). It comprises six items, with each item rated on a four-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never occurred) to 4 (always so). A higher score on this dimension indicates greater perceived maternal rejection in adolescents’ lives. [An example item is: “It happened that my mother punished me even for small offences.”] In this study, the Cronbach’s α was 0.88.

Harsh parenting

Harsh parenting was assessed using the Chinese version of the HS assessment of harsh parenting (Simons et al., 1991; Wang, 2017). It comprises four items, and each item is rated on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never like that) to 5 (always like that). A higher score on this dimension indicates greater perceived harsh parenting in adolescents’ lives. [An example item is: “When I did something wrong or made my mother angry, she lost her temper or even yelled at me.”] In this study, the Cronbach’s α was 0.86.

Autonomy support

Autonomy support was assessed using the Chinese version of the Parental Autonomy Support Scale (McPartland & Epstein, 1977; Robbins, 1994; Steinberg et al., 1992; Wang et al., 2007), which comprises 12 items measured in 2 dimensions: choice-making and opinion exchange. Each item is rated on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all true) to 5 (very true). A higher score on this dimension indicates greater perceived maternal autonomy support in adolescents’ lives. [An example item is: “My mother allows me to make choices whenever possible.”] In this study, the Cronbach’s α was 0.90.

Social adaptation

Social adaptation was assessed using the Children and Adolescent Social Adaptation Questionnaire (Miao et al., 2021), which comprises 32 items measured in 4 dimensions: interpersonal harmony, environmental identity, independent life, and learning autonomy. Each item was rated on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all true) to 5 (very true), with a higher score representing higher social adaptation. [An example item is: “I always finish my studies on time.”] In this study, the Cronbach’s α was 0.94.

Security

Security was assessed with the Security Questionnaire (Cong & An, 2004), which comprises 16 items measured on 2 dimensions: interpersonal security and certainty in control. Each item was rated on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all true) to 5 (very true), with a higher score representing higher security. [An example item is: “I always worry about bad things happening.”] In this study, the Cronbach’s α was 0.94.

Demographic variables

For the study, the mothers were asked to provide demographic information including their age, monthly income level, education level, and number of children. Adolescents were asked to provide information regarding their age and sex.

Data analysis

The data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 26.0. (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA) with the PROCESS macro (Hayes, 2013), as well as AMOS 24.0. First, the common method bias was examined, and an analysis of missing data and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) were conducted. Second, the descriptive statistics and a correlation matrix were calculated. Third, the hypothesized mediation model was examined using PROCESS 4.0.

Results

Analysis of missing data

Since some participants did not complete all three surveys, Welch’s t-test was conducted to examine whether the missing data could bias our results by comparing participants who completed the questionnaires with those who dropped out. The results showed no significant differences between mothers’ education level (t = 1.74, df = 899.37, p = .08), monthly income level (t = − 1.21, df = 881.26, p = .23), and number of children (t = − .26, df = 904.30, p = .80). These results suggest that removing incomplete questionnaires would likely not bias the results.

Common method bias

Since all measures were evaluated using the same source, common method bias (i.e., variance attributable to the measurement method rather than the constructs of the measures) might have influenced the overall results of this study. Therefore, before testing the hypotheses, common method variance was examined using the unmeasured latent method factor (Podsakoff et al., 2003). A measurement model was constructed, and each item was loaded on its respective construct (i.e., parental burnout, rejection, harsh parenting, autonomy support, social adaptation, and security). Furthermore, the common method variance factor was created and allowed to load on all items, and these paths were constrained to be equal. The latent factors were not allowed to correlate with other factors. The variance explained by the latent method factor was 5.7%, which is lower than the median of 25% reported in a previous study (Williams et al., 1989). Therefore, it was confirmed that common method bias did not impact the results.

Reliability and validity analysis

A CFA is performed to investigate construct validity, convergent validity, discrimination validity, and combination reliability (Mueller & Hancock, 2018). Due to the large number of items and small sample size, the items were parceled with an item-to-construct balance method to reduce parameter bias (Alhija & Wisenbaker, 2006).

In this study, a CFA was performed to assess construct validity using Amos 24.0 to demonstrate the fitness of the proposed six-factor model. Table 1 shows that the CFA indicators were good: χ2/df = 2.006, CFI = 0.977, TLI = 0.970, SRMR = 0.036, RMSEA = 0.050. Factor loading shows the correlation between the factor and variable (Mueller & Hancock, 2018). Furthermore, construct validity was examined by checking the factor loadings on variables. The loadings of all items were good at above 0.50. In this study, the item loadings ranged from 0.63 to 0.93, suggesting satisfactory construct validity.

Convergent validity was examined using the average variance extracted (AVE), where an AVE value of at least 0.50 is considered acceptable (Mueller & Hancock, 2018; Hair et al., 2019). As Table 2 shows, the data collected had good convergent validity.

Furthermore, discriminant validity was examined. Discriminant validity is confirmed when the square root of the AVE is greater than the correlation coefficients between the constructs (Fornell & Larcker, 1981; Hair et al., 2019). As Table 2 shows, discriminant validity is confirmed in this study.

Reliability was examined using composite reliability (CR). Reliability is considered accepted when the CR value exceeds 0.7 (Mueller & Hancock, 2018; Hair et al., 2019). As Table 2 indicates, the data collected in this study exhibited good CR.

Descriptive statistics and correlation analysis

Table 2 shows the descriptive statistics and Pearson’s correlations for all the variables. Mothers’ parental burnout was correlated with rejection (r = .16, p < .01), harsh parenting (r = .25, p < .01), autonomy support (r = − .13, p < .01), adolescents’ social adaptation (r = − .10, p < .1), and adolescents’ security (r = − .13, p <.01). Moreover, mothers’ rejection was correlated with adolescents’ social adaptation (r = − .25, p <.01) and security (r = − .39, p < .01), and their harsh parenting with adolescents’ social adaptation (r = − .30, p < .01) and security (r = − .33, p < .01). Finally, mothers’ autonomy support was also correlated with adolescents’ social adaptation (r = .42, p < .01) and security (r = .46, p < .01).

Hypotheses testing

All hypotheses were tested using the conditional process analysis program PROCESS, which computes ordinary least squares regressions to test for direct and indirect effects (Hayes, 2013). We employed PROCESS Model 4 to estimate the regression coefficients and follow-up bootstrap analyses with 5000 bootstrap samples to estimate the 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals for specific and total indirect effects. The results are presented in Figs. 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6.

Mothers’ parental burnout was found to be positively related to mothers’ rejection (β = 0.16, p < .01), and mothers’ rejection was negatively related to adolescents’ social adaptation (β= − 0.24, p < .001). The indirect effect of rejection was significant (indirect effect = − 0.024, SE = 0.01, 95%CI [− 0.05, − 0.01]). In addition, mothers’ rejection was negatively related to adolescents’ security (β= − 0.38, p < .01). The indirect effect was significant (indirect effect = − 0.06, SE = 0.03, 95%CI [− 0.12, − 0.02]).

Mothers’ parental burnout was positively related to mothers’ harsh parenting (β = 0.25, p < .001), and their harsh parenting was negatively related to adolescents’ social adaptation (β = − .29, p < .001). The indirect effect of rejection was significant (indirect effect = − .05, SE = .01, 95%CI [− .07, − .02]). Furthermore, mothers’ rejection was negatively related to adolescents’ security (β= − .32, p < .001). The indirect effect was significant (indirect effect = − .08, SE = .03, 95%CI [− .14, − .04]).

Mothers’ parental burnout was negatively related to mothers’ autonomy support (β= − .13, p < .01), and mothers’ autonomy support was positively related to adolescents’ social adaptation (β = .43, p < .001). The indirect effect of autonomy support was found to be significant (indirect effect = − .03, SE = .01, 95%CI [− .06, − 0.01]). In addition, mothers’ autonomy support was positively related to adolescents’ security (β = .46, p < .001). Finally, the indirect effect was found to be significant (indirect effect = − .06, SE = .03, 95%CI [− .11, − 0.02]).

Discussion

This study examined the association between mothers’ parental burnout with adolescents’ social adaptation and security through the mediating effects of parenting styles. The sample included adolescents and their mothers. In general, our results support all our hypotheses.

Parental burnout negatively affects adolescents’ social adaptation and security. First, studies have shown that adolescents’ level of social adaptation increases with an increase in their connectedness to social relationships, and parent–child connectedness is the most significant part thereof (Lee & Robbins, 1995). However, exhausted parents detach themselves emotionally and ignore their children’s emotional demands to protect themselves from further burnout (Roskam et al., 2017). This may decrease social connectedness with adolescents, worsen the development of parent–child relationships, and result in a lower level of social adaptation and an increase in social adaptation problems among adolescents (Lee et al., 2001). Therefore, the direct impact of mothers’ parental burnout on adolescents’ social adaptation showed that mothers who are burned out may distance themselves from adolescents (Roskam et al., 2017; Mikolajczak et al., 2019). This may reduce parent–child connectedness and further harm the development of social adaptation in adolescents (Lee et al., 2001). These results are aligned with those of previous research showing that mothers’ parental burnout had predictive effects on children’s internalizing and externalizing problem behaviors (Chen et al., 2021).

Second, in general, children receive adequate, consistent, and coherent love from their parents. They experience security, extended trust in others, self-respect, a sense of certainty, and control over reality or the future, which are provided to them by their parents (Erikson, 1950). However, burned-out parents no longer enjoy being with their children and lose parental fulfillment to the point that they are unable to devote the same love and attention as they once did (Roskam et al., 2017). Furthermore, parental burnout is associated with higher marital conflicts (Mikolajczak et al., 2019) and may destabilize the family environment. These negative changes lead adolescents to lose a sense of certainty over reality and belonging to the family, which results in their feeling a lack of security (Allen et al., 2003; Huang et al., 2017). Therefore, mothers’ parental burnout was found to predict adolescents’ security over time.

This study found that parenting style had predictive effects on adolescents’ social adaptation and security. According to Darling and Steinberg (1993), parenting styles are perceivable attitudes of parents toward the child that create an emotional climate in which the parents’ behavior is expressed. It has been shown that adolescents may display higher levels of social adaptation when parents use positive parenting styles such as warmth and encouragement. Nevertheless, when parents use negative parenting styles such as harsh parenting, adolescents may display lower levels of social adaptation (Schoeps et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2021). This is consistent with the findings of the current study, which found that maternal autonomy support positively predicted adolescent social adaptation and maternal rejection, whereas harsh parenting negatively predicted it. This study also identified a direct predictive effect of maternal parenting style on adolescent security. This is aligned with the results of previous research on parenting styles and adolescent security (Gunarsa, 2008; Li et al., 2022). For instance, mothers’ positive parenting styles such as being supportive and engaged may positively predict children’s security, while their negative parenting styles including hostility and threats may negatively predict it (Li et al., 2022).

In addition, this study identified the mediating role of parenting style. According to Belsky’s (1984) process model, the stress created by a parent’s environment, as well as the support it provides, affects their parental experience, and thus, their parenting. Parental burnout is the result of chronic and overwhelming stress (Roskam et al., 2017), which can reflect the negative parental experience of the parent, which according to Belsky’s model (1984), may directly impact parenting. Therefore, parents with burnout more frequently use negative parenting styles such as rejection and harsh parenting, and less frequently use positive parenting styles like autonomy support. This result is supported by another study (Mikkonen et al., 2022). Furthermore, in parent–child interactions, mothers’ parenting styles influence their children through their behaviors (Darling & Steinberg, 1993). As mentioned, parenting styles have predictive effects on adolescents’ social adaptation and security (Zhang et al., 2021; Schoeps et al., 2020; Li et al., 2022). Thus, mothers’ parental burnout may indirectly affect adolescents’ social adaptation and security through their different parenting styles.

Theoretical and practical implications

First, this study found that parental burnout may directly affect parenting styles, which supports the parenting process model (Belsky, 1984). Parenting styles are influenced by parental experiences: Parental burnout as a negative experience may prompt parents to adopt more negative parenting styles and less positive parenting styles. Second, except for the existing literature that found a relationship between parental burnout and adolescents’ internalizing and externalizing problems (Chen et al., 2021), the present findings provide the first empirical evidence that mothers’ parental burnout is related to adolescents’ social adaptation and security, which enriches the field of research on the consequences of parental burnout.

Furthermore, mothers are considered the primary caregivers and are responsible for providing food and shelter for their children (Renk et al., 2003). The results of this study support the essential role of mothers in child development (Wang et al., 2019). Therefore, in the practical management and prevention of parental burnout, mothers should still be considered the main subject.

Limitations and future directions

Although the present study enriches our understanding of the consequences of parental burnout, several limitations should be noted. First, we only explored the negative effects of parental burnout on adolescents’ psychological development. In this study, social adaptation was selected as an extrinsic performance, and security as an intrinsic perception of psychological development. However, adolescent psychological development is multifaceted, and parental burnout may affect other aspects of it (Mikolajczak & Roskam, 2020). Future studies should thus include both positive and negative psychological development in adolescents to investigate the various consequences of parental burnout.

Second, as our data were collected at three different time points using a time-lagged design, it was impossible to collect data on all variables at each time point, which resulted in ineffective control of the variables. With this in mind, future studies should adopt other approaches to address these limitations and extend the existing body of research on parental burnout.

Third, in this study, the attrition rate is relatively high for two reasons. First, we adopted both online and offline methods of data collection, which may result in ineffectively controlled participation. However, to improve the quality of the questionnaire, adolescents and their mothers were asked to provide the last four digits of their mothers’ phone numbers, which resulted in some questionnaires being mismatched. Therefore, future studies should adopt better data collection methods to reduce the attrition rate.

Conclusions

This study makes significant contributions by elucidating the associations between parental burnout, parenting style, and adolescents’ social adaptation and security. The results showed that mothers’ parental burnout indirectly affected adolescents’ social adaptation and security through different parenting styles. Mothers should thus be aware of their crucial role in supporting and protecting their children’s development while being mindful that their parental burnout can be disruptive in the pathway of adolescent development. Thus, steps should be taken by family members and other social acquaintances to alleviate any stress faced by mothers.

Data availability

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

References

Alhija, F. N. A., & Wisenbaker, J. (2006). A Monte Carlo study investigating the impact of item parceling strategies on parameter estimates and their standard errors in CFA. Structural Equation Modeling-A Multidisciplinary Journal, 1(2), 204–228. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15328007sem1302_3.

Allen, J. P., McElhaney, K. B., Land, D. J., Kuperminc, G. P., Moore, C. W., Beirne-Kelly, O., & Kilmer, H., S. L (2003). A secure base in adolescence: Markers of attachment security in the mother-adolescent relationship. Child Development, 74(1), 292–307. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.t01-1-00536.

An, L. J., Cong, Z., & Wang, X. (2004). Research of High School Students’ security and the related factors. Chinese Mental Health Journal, 18(10), 717–722. (In Chinese).

Arrindell, W. A., Emmelkamp, P. M. G., Brilman, E., & Monsma, A. (1983). Psychometric evaluation of an inventory for assessment of parental rearing practices. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 67(3), 163–177. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb00338.

Belsky, J. (1984). The determinants of parenting: A process model. Child Development, 55(1), 83–96. https://doi.org/10.2307/1129836.

Bernier, A., Carlson, S. M., & Whipple, N. (2010). From external regulation to self-regulation: Early parenting precursors of Young Children’s executive functioning. Child Development,81(1), 326–339. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01397

Blanchard, A-L., Roskam, I., Mikolajczak, M., & Heeren, A. (2020). A network approach to parental burnout. Child Abuse & Neglect, 111, 104826. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104826.

Chang, L., Schwartz, D., Dodge, K. A., & McBride-Chang, C. (2003). Harsh parenting in relation to child emotion regulation and aggression. Journal of Family Psychology, 17(4), 598–606. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.17.4.598.

Chen, B., Qu, Y., Yang, B., & Chen, X. (2021). Chinese mothers’ parental burnout and adolescents’ internalizing and externalizing problems: The mediating role of maternal hostility. Developmental Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0001311. Advance online publication.

Cong, Z., & An, L. (2004). Develo** of Security Questionnaire and its reliability and validity. Chinese Mental Health Journal, 18(2), 97–99. (In Chinese).

Darling, N., & Steinberg, L. (1993). Parenting style as context: An integrative model. Psychological Bulletin, 113(3), 487–496. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.113.3.487.

Das, J. K., Salam, R. A., Lassi, Z. S., Khan, M. N., Mahmood, W., Patel, V., & Bhutta, Z. A. (2016). Interventions for adolescent Mental Health: An overview of systematic reviews. Journal of Adolescent Health, 59(4), S49–S60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.06.020.

Erikson, E. H. (1950). Childhood and Society. Norton.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104.

Gunarsa, S. D. (2008). Psikologi perkembangan anak dan remaja. BPK Gunung Mulia.

Hair, J. F., Anderson, R. E., Babin, B. J., & Black, W. C. (2019). Multivariate data analysis (8th ed.). Cengage Learning.

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. The Guilford.

Huang, B., Zhou, C., Li, L., Huang, H., & Liu (2017). Perceived parental conflict of Junior School Students and Security: The Mediating Effect of Resilience. China Journal of Health Psychology, 25(1), 897–902. https://doi.org/10.13342/j.cnki.cjhp.2017.06.026(In Chinese).

Jiang, J., Lu, Z., Jiang, B., & Xu, Y. (2010). Preliminary revision of the Chinese version of the simplified parenting style questionnaire. Psychological Development and Education, 26(1), 94–99. (in Chinese). https://doi.org/10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2010.01.017.

Jones, T. L., & Prinz, R. J. (2005). Potential roles of parental self-efficacy in parent and child adjustment: A review. Clinical Psychology Review, 25(3), 341–363. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2004.12.004.

Le Vigouroux, S., Scola, C., Raes, M. E., Mikolajczak, M., & Roskam, I. (2017). The big five personality traits and parental burnout: Protective and risk factors. Personality and Individual Differences, 110, 216–219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.07.023.

Lee, R. M., & Robbins, S. B. (1995). Measuring belongingness: The social connectedness and the social assurance scales. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 42(2), 232–241. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.42.2.232.

Lee, R. M., Draper, M., & Lee, S. (2001). Social connectedness, dysfunctional interpersonal behaviors, and psychological distress: Testing a mediator model. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 48(3), 310–318. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.48.3.310.

Li, F., Cao, E., & Ma, M. (2022). The Mediator Role of Empathy ability in the relationship between parenting style and sense of security in 3–6-Year-old Chinese children. International Journal of Early Childhood. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13158-021-00310-x. Advance online publication.

Lin, G.-X., & Szczygieł, D. (2022). Basic personal values and parental burnout: A brief report. Affective Science, 3(2), 498–504. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42761-022-00103-y.

Lin, G., Szczygieł, D., Hansotte, L., Roskam, I., & Mikolajczak, M. (2021). Aiming to be perfect parents increases the risk of parental burnout, but emotional competence mitigates it. Current Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01509-w. Advance online publication.

Liu, Q., & Wang, Z. (2021). Associations between parental emotional warmth, parental attachment, peer attachment, and adolescents? character strengths. Children and Youth Services Review. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105765

Mcdowell, D. J., & Parke, R. D. (2010). Parental control and affect as predictors of children’s display rule use and social competence with peers. Social Development, 14(3), 440–457. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9507.2005.00310.x.

McPartland, J. M., & Epstein, J. L. (1977). Open schools and achievement: Extended tests of a finding of no relationship. Sociology of Education, 50(2), 133–144. https://doi.org/10.2307/2112375.

Meeussen, L., & Laar, C. V. (2018). Feeling pressure to be a perfect mother relates to parental burnout and career ambitions. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 2113. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02113.

Miao, H., Guo, C., Wang, T., Liu, X., & Zhang, Y. (2021). On reliability and validity evaluation and application of children and adolescent Social Adaptation Questionnaire. Journal of Southwest China Normal University (Natural Science Edition), 46(10), 106–113. https://doi.org/10.13718/j.cnki.xsxb.2021.10.016.

Mikkonen, K., Veikkola, H-R., Sorkkila, M., & Aunola, K. (2022). Parenting styles of Finnish parents and their associations with parental burnout. Current Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03223-7. Advance online publication.

Mikolajczak, M., & Roskam, I. (2020). Parental burnout: Moving the focus from children to parents. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 177, 7–13. https://doi.org/10.1002/cad.20376.

Mikolajczak, M., Raes, M. E., Avalosse, H., & Roskam, I. (2018a). Exhausted parents: Socio-demographic, child-related, parent-related, parenting and family-functioning correlates of parental burnout. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 27(2), 602–614. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-017-0892-4.

Mikolajczak, M., Brianda, M. E., Avalosse, H., & Roskam, I. (2018b). Consequences of parental burnout: Its specific effect on child neglect and violence. Child Abuse & Neglect, 80(1), 134–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.03.025.

Mikolajczak, M., Gross, J. J., & Roskam, I. (2019). Parental burnout: What is it, and why does it Matter? Clinical Psychological Science, 7(6), 1319–1329. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702619858430.

Mueller, R. O., & Hancock, G. R. (2018). Structural equation modeling. The Reviewer?s Guide to Quantitative Methods in the Social Sciences (pp. 445–456). Routledge.

Nie, Y., Lin, C., Pang, Y., Ding, L., & Gan, X. (2008). The development characteristic of adolescents’ Social Adaptive Behavior. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 40(9), 1013–1020. https://doi.org/10.3724/SP.J.1041.2008.01013(In Chinese).

Norberg, A. L., Mellgren, K., Winiarski, J., & Forinder, U. (2014). Relationship between problems related to child late effects and parent burnout after pediatric hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Pediatric Transplantation, 18(3), 302–309. https://doi.org/10.1111/petr.12228.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879.

Raudasoja, M., Sorkkila, M., & Aunola, K. (2022). Self-Esteem, socially prescribed perfectionism, and parental burnout. Journal of Child and Family Studies. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-022-02324-y. Advance online publication.

Renk, K., Roberts, R., Roddenberry, A., Luick, M., Hillhouse, S., Meehan, C., & Phares, V. (2003). Mothers, fathers, gender role, and time parents spend with their children. Sex Roles, 48(7–8), 305–315. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022934412910.

Robbins, R. J. (1994). An assessment of perceptions of parental autonomy support and control: Child and parent correlates. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Rochester.

Roskam, I., Raes, M. E., & Mikolajczak, M. (2017). Exhausted parents: Development and preliminary validation of the parental burnout inventory. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 163. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00163.

Roskam, I., Brianda, M. E., & Mikolajczak, M. (2018). A Step Forward in the conceptualization and measurement of parental burnout: The parental burn-out Assessment (PBA). Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 758. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00758.

Sánchez-Rodríguez, R., Perier, S., Callahan, S., & Séjourné, N. (2019). Revue De La littérature relative Au burnout parental. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie Canadienne. https://doi.org/10.1037/cap000016. Advance online publication.

Schoeps, K., Valero-Moreno, S., Perona, A. B., Pérez-Marín, M., & Montoya-Castilla, I. (2020). Childhood adaptation: Perception of the parenting style and the anxious-depressive symptomatology. Journal for Specialists in Pediatric Nursing, 25(4), e12306. https://doi.org/10.1111/jspn.12306.

Shao, L., Dong, Y., & Zhang, D. H. (2021). Effects of security on social trust among Chinese adults: Roles of life satisfaction and ostracism. The Journal of Social Psychology, 161(5), 560–569. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.2020.1871312.

Shea, S. E., & Coyne, L. W. (2011). Maternal dysphoric mood, stress, and parenting practices in mothers of Head Start preschoolers: The role of experiential avoidance. Child & Family Behavior Therapy, 33(3), 231–247.

Shu, Z., He, Q., Li, X., Zhang, J., Zhang, Y., & Fang, X. (2016). Effect of maternal stress on preschoolers’ creative personality: The mediating role of mothers’ parenting styles. Psychological Development and Education, 32(3), 276–284. https://doi.org/10.16187/i.cnki.issn1001-4918.2016.03.03(In Chinese).

Siemsen, E., Roth, A., & Oliveira, P. (2010). Common method bias in regression models with linear, quadratic, and interaction effects. Organizational Research Methods, 13(3), 456–476. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428109351241.

Simons, R. L., Whitbeck, L. B., Conger, R. D., & Wu, C. (1991). Intergenerational transmission of harsh parenting. Developmental Psychology, 27(1), 159–171. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.27.1.159.

Song, T., Wang, W., Chen, S., Li, W., & Li, Y. (2023). Examining the effects of positive and negative perfectionism and maternal burnout. Personality and Individual Differences. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2023.112192

Sorkkila, M., & Aunola, K. (2020). Risk factors for parental burnout among Finnish parents: The role of socially prescribed perfectionism. Journal of Child and Family Studies. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01607-1. Advance online publication.

Steinberg, L., Lamborn, S. D., Dornbusch, S. M., & Darling, N. (1992). Impact of parenting practices on adolescent achievement: Authoritative parenting, school involvement, and encouragement to succeed. Child Development, 63(5), 1266–1281. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb01694.x.

Wang, M. (2017). Harsh parenting and peer acceptance in Chinese early adolescents: Three child aggression subtypes as mediators and child gender as moderator. Child Abuse & Neglect, 63, 30–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2016.11.017.

Wang, Q., Pomerantz, E. M., & Chen, H. (2007). The role of parents’ control in early adolescents’ psychological functioning: A longitudinal investigation in the United States and China. Child Development, 78(5), 1592–1610. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01085.x.

Wang, M., Wu, X., & Wang, J. (2019). Paternal and maternal harsh parenting and Chinese adolescents’ social anxiety: The different mediating roles of attachment insecurity with fathers and mothers. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260519881531. Advance online publication.

Wang, W., Wang, S., Cheng, H., Wang, Y., & Li, Y. (2021). Revision of the simplified parental burnout Scale Chinese version. Chinese Journal of Mental Health,35(11), 941–946. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1000-6729.2021.11.010. (In Chinese).

Wang, W., Wang, S., Chen, S., & Li, Y. (2022a). Parental burnout and job burnout in working couples: An actor-partner interdependence model. Journal of Family Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000953. Advance online publication.

Wang, W., Wang, Y., Song, T., & Li, Y. (2022b). Parental burnout and children’s problem behaviors: The mediating role of children’s self control. Journal of **nyang Normal University,42(3), 84–89. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03667-x. (In Chinese).

Wang, W., Song, T., Chen, S., Li, Y., & Li, Y. (2023). Work-family enrichment and parental burnout: The mediating effects of parenting sense of competence and parenting stress. Current Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04874-w. Advance online publication.

Williams, L. J., Cote, J. A., & Buckley, M. R. (1989). Lack of method variance in self-reported affect and perceptions at work: Reality or artifact? Journal of Applied Psychology, 74(3), 462–468. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.74.3.462.

Yang, B., Chen, B., Qu, Y., & Zhu, Y. (2021). Impacts of parental burnout on Chinese youth?s Mental health: The role of parents? Autonomy support and emotion regulation. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-021-01450-y

Yin, H., Qian, S., Huang, F., Zeng, H., Zhang, C., & Ming, W. (2021). Parent-child attachment and Social Adaptation Behavior in Chinese College students: The mediating role of School Bonding. Frontiers Psychology, 12, 711669. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.711669.

Yu, J., & Wang, J. (2019). Relationship between maternal marital satisfaction and adolescent maladaptive perfectionism: The Mediating Effect of Psychological Control. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 27(02), 367–372. https://doi.org/10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2019.02.032(In Chinese).

Zhang, G., Liang, M., & Liang, Z. (2021). A longitudinal study of the influence of parenting styles on Social Adjustment of Preschool Children: Mediating effects of Self-control. Psychological Development and Education, 37(6), 800–807. https://doi.org/10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2021.06.06(In Chinese).

Zhang, H., Hu, Q., & Mao, Y. (2023). Parental burnout and adolescents’ phubbing: Understanding the role of parental phubbing and adolescents, psychological distress. School Psychology International. https://doi.org/10.1177/014303432312018. Advance online publication.

Zou, W., Wang, H., & **e, L. (2021). Examining the effects of parental rearing styles on first-year university students’ audience-facing apprehension and exploring self-esteem as the mediator. Current Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02287-1. Advance online publication.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all those who participated in this study.

Funding

This study was supported by the Chinese National Social Science Fund (23BRK035).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Ethics approval

This study, which involved human participants, was reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Institute of Psychology and Behavior, Henan University. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Song, T., Wang, W., Chen, S. et al. Mothers’ parental burnout and adolescents’ social adaptation and security: the mediating role of parenting style. Curr Psychol (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-06045-x

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-06045-x