Abstract

Despite the ubiquity of workaholism and workplace incivility, extant research lacks sufficient empirical support on the underlying mechanisms between them, which hinders curtailing the uncivil behavior of workaholics. To systematically investigate the underlying mechanisms, we proposed two mediators: emotional exhaustion and psychological entitlement. The former illustrates why workaholics engage in uncivil behaviors uncontrollably from the existing conservation of resources perspective, which captures the behavioral dimension of workaholism. The latter explains why workaholics engage in workplace incivility voluntarily from a novel moral licensing perspective, which captures the overlooked cognitive dimension of workaholism. Further, we incorporate supervisor-subordinate guanxi as a critical moderator that helps differentiate the above two mediators. Results across two studies suggested that supervisor-subordinate guanxi alleviates the indirect effects of workaholism on workplace incivility via emotional exhaustion, while magnifying the indirect effects via psychological entitlement. Overall, these findings provide evidence that workaholism can also psychologically free employees to engage in subsequent uncivil behaviors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Workaholism refers to “the uncontrollable need to work incessantly” (Oates, 1971, p. 1). Scholars have suggested that workaholism consists of a behavioral dimension (working excessively) as well as a cognitive dimension (working compulsively) (Schaufeli et al., 2009; Xu et al., 2023). Prior studies found that workaholism can lead to workplace incivility (i.e., “low-intensity deviant workplace behavior with ambiguous intent to harm”; Andersson & Pearson, 1999, p. 457). Drawing on the conservation of resources (COR) theory (Halbesleben et al., 2014), extant research contends that workaholics’ excessive allocation of time and energy toward work increases their job stress level, decreases their psychological capital, and hampers work-family enrichment (Lanzo et al., 2016; Taheri et al., 2021). Consequently, they exhibit uncivil behaviors for not having sufficient self-regulatory capacity (Balducci et al., 2021). However, these mediators mentioned above mainly capture the behavioral dimension while overlooking the cognitive dimension of workaholism, thereby suggesting the potential existence of significant mediators associated with the cognitive aspect. Given the ubiquity of workplace incivility and its detrimental effects in organizational settings (Chris et al., 2022; Han et al., 2022), it is imperative to open the “black box” further in order to curtail this costly behavior of workaholics. Thus, the primary goal of this study is to systematically unveil the mechanisms through which workaholism leads to workplace incivility.

Undoubtedly, the COR theory does contribute to our understanding of the aforementioned linkage by capturing the behavioral component of workaholism. Nevertheless, given the insufficient empirical support in existing research (Balducci et al., 2021), our study reevaluates this rationale by incorporating emotional exhaustion, which signifies a state of resource depletion within the COR theory (Lin et al., 2019), as an underlying mechanism to validate the resources depleting nature of workaholism. More importantly, the cognitive aspect of workaholism entails an inherent compulsion to work hard (Taris & de Jonge, 2024; Xu et al., 2023). As per Clark et al. (2020), it is the introjected regulation of workaholics, such as proving self-worth, rather than their personal volition, that drives them to set extremely high performance standards for themselves and engage in excessive work. Consequently, workaholics perceive themselves as exerting more effort and making greater contributions to the organization compared to their colleagues (Balducci et al., 2018; Spagnoli et al., 2021). According to moral licensing theory (Merritt et al., 2010), this heightened sense of self-worth leads workaholics to believe they are superior and deserve special treatment (Ahmad et al., 2021; Grubbs & Exline, 2016), thereby justifying their occasional uncivil behaviors. Hence, this study argues that workaholism can also foster workplace incivility by evoking feelings of psychological entitlement, or the “pervasive sense that one deserves more and is entitled to more than others”(Campbell et al., 2004, p. 31).

Moreover, failing to differentiate between emotional exhaustion and psychological entitlement as mediators may result in inaccurate interventions for workplace incivility among workaholics. Therefore, we introduce supervisor-subordinate guanxi (SSG), or “a personal relationship between a supervisor and a subordinate developed largely from nonwork related social interactions that might extended into the workplace” (Guan & Frenkel, 2019, p. 1753), as a crucial moderator to facilitate the distinction between the above two mechanisms. Given the authority supervisors wield over scarce resources, supervisors can provide good guanxi subordinates with additional access to resources and extra opportunities, thereby elevating their prospects for promotions as well as other rewards (Miao et al., 2020; Ni et al., 2024). Therefore, within the COR framework, preferential treatment from supervisors in a high-quality SSG can serve as supplementary resources that alleviate workaholics’ emotional exhaustion (Stein et al., 2021), thus leading to reduced engagement in workplace incivility. However, from the moral licensing perspective, this research posits that supervisors’ special treatment in high-quality SSG amplifies workaholics’ psychological entitlement by reinforcing their perceived contribution and self-importance relative to colleagues (Grubbs & Exline, 2016; Ogunfowora et al., 2022), thus leading them to engage more frequently in workplace incivility.

Our study makes three main theoretical contributions. Firstly, we provide novel insights into the linkage between workaholism on workplace incivility. Previous research mainly adopted a COR perspective to examine the underlying mechanisms (e.g., psychological capital) between workaholism and workplace incivility, contending that depletion of resources leads workaholics to engage in uncivil behaviors uncontrollably (Lanzo et al., 2016; Taheri et al., 2021). In this study, we introduce psychological entitlement as an additional mediating mechanism based on moral licensing theory. We argue that workaholics’ inflated perception of self-worth and their contributions serve as justifications for their uncivil behaviors, thereby enabling them to engage in such behaviors at will. To this end, the second contribution of our study is that we enhance understanding of the connotation of workaholism. Extant research emphasizing heavy involvement in work mainly captures the behavioral aspect of workaholism from the COR perspective, while ignoring its cognitive aspect (Xu et al., 2023). Our study uncovers that workaholism also engenders psychological entitlement, thereby illuminating the pathological manifestation of heavy work investment (Di Stefano & Gaudiino, 2019). In doing so, our study sheds light on the concealed motivation underlying workaholism and accentuates its cognitive facet. Thirdly, this study addresses the call for more research on investigating how moderators influence the effects of workaholism on outcomes (Clark et al., 2016). In this study, we identify SSG as a critical contingency factor for understanding the impact of workaholism. Interestingly, our finding reveals that SSG mitigates the indirect effect of workaholism on workplace incivility via emotional exhaustion while strengthening the indirect effect via psychological entitlement.

Our study begins with the theory and hypotheses for our conceptual model. Subsequently, we proceeded to conduct two studies to validate it. Study 1 examined the indirect effect of workaholism on workplace incivility through emotional exhaustion and psychological entitlement. Study 2 examined the integrated model where the indirect effect of workaholism on workplace incivility (via emotional exhaustion and psychological entitlement) is moderated by SSG. Finally, this work discussed the theoretical and practical contributions of our study, acknowledge its limitations, and suggest potential avenues for future investigation.

Theory and hypotheses

A COR perspective on the mediating role of emotional exhaustion

COR theory posits that individuals actively strive to acquire, defend, and retain resources in order to achieve their goals (Halbesleben et al., 2014; Hobfoll, 1989). According to the COR theory, losing resources engenders greater psychological harm than gaining resources. This psychological harm often manifests as emotional exhaustion, leading individuals to refrain from further resource expenditure for self-protection (Halbesleben et al., 2014). Notably, feelings of emotional exhaustion become particularly salient when there is a lack of resource acquisition following significant expenditure (Fan et al., 2020; Lin et al., 2019). Taking together, the COR theory provides insight into why workaholics experience heightened emotional exhaustion and subsequently engage in workplace incivility.

Specifically, workaholism is positively related to emotional exhaustion. The behavioral aspect of workaholism indicates that workaholics continuously spend excessive time and energy on work-related activities, disregarding the necessity of recovery (Farasat et al., 2021). Despite their high productivity, workaholics may not receive adequate rewards due to their poor social relations and negative performance evaluation from coworkers (Clark et al., 2016; Spence & Robbins, 1992). Besides, their excessive job involvement reduces the time available for social entertainment (Geurts & Sonnentag, 2006). Moreover, workaholics’ heavy workload hinders their contributions to family domain. As a consequence, they experience increased negative interactions and conflict with family members while receiving less emotional and instrumental support from them (Clark et al., 2021). According to the COR theory, due to the lack of resource gain following their significant resource expenditure, workaholics are more likely to experience emotional exhaustion (Halbesleben et al., 2014). Indeed, prior research has already revealed a robust relationship between workaholism and overall burnout as well as its specific facets of emotional exhaustion (Balducci et al., 2018, 2021; Clark et al., 2016). We further propose that emotional exhaustion is positively associated with workplace incivility. Scholars have depicted withstanding hostile and aggressive impulses as an effortful process that requires self-regulatory resource investment and, thus, drains individuals’ resource base (Dionisi & Barling, 2019; Fan et al., 2020; Lam et al., 2017; Qin et al., 2018). Logically, then, emotionally exhausted workaholics may be less inclined to invest their remaining resources in restraining aggressive impulses due to limited self-regulatory capacity resulting from resource depletion(Banks et al., 2012; Thau & Mitchell, 2010). Following this rationale, emotionally exhausted workaholics are more likely to engage in uncivil behaviors toward others. In fact, prior research already has illustrated individuals’ resource deprivation as a proximal cause of aggressive workplace behaviors (Khan et al., 2021; Rafique, 2023). In sum, given workaholism is more likely to trigger emotional exhaustion and that emotional exhaustion can subsequently lead to workplace incivility, we propose that emotional exhaustion mediates the relationship between workaholism and workplace incivility. Thus, this study hypothesizes:

H1

Workaholism has a positive indirect effect on workplace incivility via emotional exhaustion.

A moral licensing perspective on the mediating role of psychological entitlement

Moral licensing theory is grounded in the moral balance model, which posits that individuals with strong moral values may occasionally engage in behaviors perceived as morally questionable when confronted with ethical dilemmas (Nisan, 1991). Moral licensing theory holds that engaging in socially desirable and morally commendable behaviors can grant individuals a sense of moral and/or psychological permission, enabling them to rationalize subsequent involvement in unethical behaviors (Merritt et al., 2010; Zhang & Du, 2023). In other words, performing socially desirable actions can psychologically justify one’s subsequent immoral behaviors by reducing their concerns about losing moral credits. For example, prior research revealed that employee volunteering promotes the likelihood of engaging in workplace deviance (Loi et al., 2020). Also, leaders’ ethical behaviors were found to raise their abusive behaviors the next day (Lin et al., 2016). According to moral licensing theory, this study proposes that psychological entitlement mediates the effect of workaholism on workplace incivility.

Extant research suggests a similarity between moral credentials and the experience of psychological entitlement, wherein engaging in virtuous behavior leads to a subsequent sense of moral laxity (Polman et al., 2013; Sachdeva et al., 2009). The cognitive aspect of workaholism indicates that workaholics are driven to work compulsively because of introjected motivation (Van Beek et al., 2012). Such introjected motivation can be the result of perfectionism, which propels workaholics to set unreasonably high standards for themselves (Taris et al., 2010). Excessive hard work coupled with standards of perfection makes workaholics believe that their hard work should be beneficial to their organizations and their performance outperforms their colleagues (Balducci et al., 2018; Yam et al., 2017). According to moral licensing theory, workaholics in this case may take it for granted that they deserve more than others, enhancing their feeling that they are superior to others and should be specially treated (Grubbs & Exline, 2016). Generally, such feelings evoke their feelings of psychological entitlement.

We further posit that psychological entitlement positively influences workplace incivility. According to moral licensing theory, highly entitled workaholics take it for granted to engage in uncivil behaviors because their inflated feelings of self-worth help them rationalize such immoral behaviors (Lee et al., 2019). In other words, highly entitled workaholics truly believe that they are above organizational rules and thus have limited moral concerns about their socially irresponsible uncivil behaviors (Lee et al., 2019; Yam et al., 2017). Moreover, prior research has provided empirical evidence indicating that psychological entitlement exerts a positive influence on individuals’ engagement in aggressive behaviors, financial misconduct, and workplace deviant behaviors (Campbell et al., 2004; Li et al., 2022; Qin et al., 2020). Taking together, this research argues that workaholism may lead to workplace incivility by increasing psychological entitlement. Hence, this study hypothesizes:

H2

Workaholism has a positive indirect effect on workplace incivility via psychological entitlement.

The moderating role of SSG

SSG refers to the informal personal connection between supervisors and their subordinates outside the workplace, which is built on long-term mutual benefits and interests (Wong et al., 2003). Consequently, supervisors prefer to offer special treatment to subordinates within a high-quality SSG, including additional access to valuable resources and inside information, favorable participation in the organizational decision-making process, higher performance evaluations, and increased promotional opportunities (Cheung & Wu, 2011; Miao et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2016; Zhong et al., 2022). However, subordinates within low-quality guanxi have greater difficulties in obtaining resources and recognition from their supervisors and organizations (Cheung & Wu, 2011; Guan & Frenkel, 2019). In this study, we argue that SSG plays a critical role in differentiating the mediating role of emotional exhaustion and psychological entitlement between workaholism and workplace incivility.

Drawing upon the principles of COR theory, we argue that the provision of special treatment associated with high-quality SSG can serve as critical social resources that effectively alleviate workaholics’ emotional exhaustion and subsequent workplace incivility (Stein et al., 2021). As previously mentioned, the primary reason why workaholism results in symptoms of emotional exhaustion lies in that they can hardly get replenishment of resources following excessive expenditure in the workplace (Balducci et al., 2021; Halbesleben et al., 2014). A high-quality SSG brings both instrumental and affective resources to workaholics (Guan & Frenkel, 2019), thereby mitigating the positive linkage between workaholism and emotional exhaustion by replenishing their resource pool (Halbesleben et al., 2014). On the contrary, in a low-quality SSG context, workaholics suffer more severe emotional exhaustion due to the greater difficulties in acquiring resources and receiving recognition from supervisors and organizations (Wu & Ma, 2023), making it even harder for them to compensate for their resources losses through replenishment (Halbesleben et al., 2014).

Given emotional exhaustion serves as an underlying mechanism that links workaholism and workplace incivility, and that the positive relationship between workaholism and emotional exhaustion is contingent on the quality of SSG. Hence, it is logical to hypothesize that SSG also moderates the indirect linkage between workaholism and workplace incivility with emotional exhaustion. Specifically, given workaholics within high-quality SSG are less likely to feel emotionally exhausted, we expect the indirect effect of workaholism on workplace incivility via emotional exhaustion to be less pronounced. Conversely, the indirect linkage between workaholism and workplace incivility through emotional exhaustion should be stronger for workaholics within low-quality SSG. Therefore, this study hypothesizes:

H3a

SSG moderates the positive relationship between workaholism and emotional exhaustion, such that this positive effect is more pronounced when SSG is low rather than high.

H3b

SSG moderates the positive indirect relationship between workaholism and workplace incivility via emotional exhaustion, such that the indirect effect is more pronounced when SSG is low rather than high.

As stated above, the reason why workaholics develop a sense of entitlement is due to their inflated perceptions of self-worth and contributions (Merritt et al., 2010; Zhang & Du, 2023). Drawing on moral licensing theory, this study posits that supervisors’ bestowal of special treatment within a high-quality SSG can function as crucial contextual cues regarding the contributions of workaholics to organizations, thereby influencing the development of psychological entitlement and their subsequent engagement in uncivil behaviors. Specifically, within a high-quality SSG, workaholics may perceive themselves as having high status than their colleagues because supervisors grant them privileges such as access to valuable resources and information, which may not be available to others (Cheung et al., 2009). Besides, their opinions and suggestions are more likely to be acknowledged and adopted by supervisors and organizations, further enhancing their perceived importance relative to colleagues (Cheung & Wu, 2011; Miao et al., 2020). Consequently, these workaholics are prone to experience an exaggerated sense of self-worth, which induces heightened levels of psychological entitlement (Qin et al., 2020). In contrast, within a low-quality SSG context, the prestigious feelings experienced by workaholics will diminish since they may encounter difficulties in receiving recognition within the organization (Zhang & Gill, 2019). Consequently, they are less inclined towards develo** inflated perceptions of self-worth and contributions, which results in reduced feelings of entitlement.

Given psychological entitlement mediates the relationship between workaholism and workplace incivility, and that the positive linkage between workaholism and psychological entitlement is contingent on the quality of SSG. Hence, it is logical to hypothesize that SSG also moderates the indirect linkage between workaholism and workplace incivility with psychological entitlement. Specifically, given workaholics within high-quality SSG likely develop an amplified sense of entitlement, we expect the indirect effect of workaholism on workplace incivility via psychological entitlement to be stronger. Conversely, the indirect linkage between workaholism and workplace incivility through psychological entitlement should be less pronounced for workaholics within low-quality SSG. Hence, this study hypothesizes:

H4a

SSG moderates the positive relationship between workaholism and psychological entitlement, such that this positive effect is stronger when SSG is high rather than low.

H4b

SSG moderates the positive indirect relationship between workaholism and workplace incivility via psychological entitlement, such that the indirect effect is stronger when SSG is high rather than low.

Study 1

Method

Sample and procedure

To validate the mediating role of emotional exhaustion and psychological entitlement, this research collected data from participants and their co-workers in two companies via questionnaires at two time periods over one month. Before distributing the survey questionnaires, we first clearly informed participants about the voluntary nature of their participation. Additionally, we explained the internal research purpose and assured them that their survey information would be kept confidential and anonymous. At time 1, 267 participants rated the workaholism scale and their demographic characteristics. At time 2 (one month after time 1), 231 participants filled in a follow-up questionnaire rating their emotional exhaustion and psychological entitlement. Meanwhile, we randomly invited one co-worker of the focal participants to assess his or her workplace incivility. The final sample included 182 matched effective questionnaires, resulting in a response rate of 68.16%. Among the 182 participants, 41.2% were male, the average age was 33.93, 44.2% had completed a college degree, and 70.9% had worked in the current organization for less than 6 years.

Measures

Survey items were back-translated following procedures from Brislin (1983). Our research adopted a response format of 1 = “strongly disagree” to 5 = “strongly agree”, unless otherwise noted. Participants assessed workaholism with the 9-item scale from Robinson (1999) (e.g., “I feel guilty when I am not working on something”); emotional exhaustion with the 5-item scale from Schaufeli et al. (1996) (e.g., I feel emotionally drained from my work”); psychological entitlement with the 9-item scale from Campbell et al. (2004) (e.g., “I demand the best because I’m worth it”). The co-worker rated the focal participant’s workplace incivility with the 7-item scale from Blau and Andersson (2005). The lead-in phrase was “In the past year, how often have this person exhibited the following behaviors to someone at work (e.g. co-worker, other employees, supervisor)?”. A sample item reads “Addressed someone in unprofessional terms either publicly or privately” (1 = “never”, 5 = “many times”). We also concluded focal participants’ gender, age, education, and tenure as control variables.

Results

First, we conducted Harman’s single-factor test to examine the common method bias (CMB) in our study. We draw out 4 factors and the largest explains 34.161% of the variance, which suggested that there were no serious CMB problems (Podsakoff et al., 2003). Then, we conducted confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) to assess the discriminant validity of the scale measures in this study. Results in Table 1 indicated that the four-factor model provides significantly better fit to the data than the other three models (χ2 = 704.991, df = 399, χ2/df = 1.77, CFI = 0.923, TLI = 0.916, RMSEA = 0.065).

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics, inter-correlations, and reliabilities of the variables. Consistent with our hypotheses, workaholism was positively related to emotional exhaustion (r = 0.293, p < 0.01) and psychological entitlement (r = 0.299, p < 0.001). In addition, emotional exhaustion and psychological entitlement respectively had a positive correlation with workplace incivility (r = 0.440, p < 0.001; r = 0.394, p < 0.001).

This study conducted multiple regressions in SPSS 22.0 to test the proposed hypotheses (see Table 3 for results). H1 proposed that emotional exhaustion mediates the effect of workaholism on workplace incivility. As shown in Table 3, workaholism was positively related to emotional exhaustion (β = 0.347, p < 0.001; see Model 2 in Table 3), and emotional exhaustion was positively related to workplace incivility (β = 0.318, p < 0.001; see Model 7 in Table 3). Also, the positive effect of workaholism on workplace incivility weakens from β = 0.391, p < 0.001 to β = 0.281, p < 0.001 when we entered emotional exhaustion in the model. Therefore, emotional exhaustion partially mediates the positive effect of workaholism on workplace incivility (Baron & Kenny, 1986). Hence, H1 was supported.

H2 argued that psychological entitlement mediates the effect of workaholism on workplace incivility. Similarly, as shown in Table 3, workaholism was positively related to psychological entitlement (β = 0.309, p < 0.001; see Model 4 in Table 3), and psychological entitlement was positively related to workplace incivility (β = 0.299, p < 0.001; see Model 8 in Table 3). The positive effect of workaholism on workplace incivility weakened from β = 0.391, p < 0.001 to β = 0.299, p < 0.001 when including psychological entitlement. Therefore, psychological entitlement partially mediates the positive effects of workaholism on workplace incivility (Baron & Kenny, 1986). Hence, H2 received support.

Besides, this research adopted bootstrap** procedures with macro program PROCESS in SPSS 22.0 to further examine the above mediating effects. Bootstrap** times were 5000. As shown in Table 4, the linkage between workaholism and workplace incivility via emotional exhaustion was positive and significant (indirect effect = 0.149, SE = 0.048, 95% CI [0.006, 0.248], excluding 0), and the relationship between workaholism and workplace incivility via psychological entitlement was also positive and significant (indirect effect = 0.124, SE = 0.055, 95% CI [0.004, 0.252], excluding 0) (Hayes, 2015). Therefore, H1 and H2 received further support.

Study 2

Method

Sample and procedure

To further validate our proposed framework, this research collected employee–supervisor dyadic data with a snowball sampling technique, which has been adopted to assess deviant workplace behaviors in prior studies (Greenbaum et al., 2012; Harold & Holtz, 2015). Data were collected from four companies via questionnaires at three time points over two months. Prior to distributing the survey questionnaires, we explicitly informed participants about the voluntary nature of their participation. Moreover, we elucidated the internal research purpose of the survey and ensured that their survey information would be treated with utmost confidentiality and anonymity. At time 1, 482 participants rated their demographic characteristics, workaholism, and SSG. At time 2 (one month after time 1), 393 participants filled in a follow-up questionnaire rating their emotional exhaustion and psychological entitlement. At time 3 (two months after time 1), 345 participants’ direct supervisors rated their employees’ workplace incivility. The final sample included 298 employee–supervisor dyads, yielding a response rate of 61.83%. Among the 298 employees, 156 were male (52.3%). Age was assessed using age bands as follows (along with percentage of sample in each band): below 30 years (29.5%), 31 to 40 years (47.7%), 41 to 50 years (21.5%), over 50 years (1.3%). Tenure was reported as follows: less than 3 years (50.0%), 4 to 6 years (16.4%), 7 to 9 years (10.7%), over 10 years (22.8%). In terms of education, 2.3% had a high school diploma or lower, 19.5% had completed a college degree, 59.7% held a bachelor degree, 18.5% had postgraduate qualifications or higher.

Measures

For survey items, this research followed a back-translated procedure (Brislin, 1983). Workaholism was measured using the 10-item Dutch Work Addiction Scale from Schaufeli et al. (2009). A sample item reads “I feel that there’s something inside me that drives me to work hard” (1 = “never”, 5 = “always”). SSG was measured with the 6-item scale from Law et al. (2000). A sample item reads “When there are conflicting opinions, I will definitely stand on my supervisor’s side” (1 = “strongly disagree”, 5 = “strongly agree”). Emotional exhaustion was assessed with the 3-item scale from Watkins et al. (2014). A sample item reads “I feel emotionally drained from my work” (1 = “never”, 5 = “always”). Psychological entitlement was assessed with the 4-item scale developed by Yam et al. (2017). An example item is “I honestly feel I’m just more deserving than others” (1 = “strongly disagree”, 5 = “strongly agree”). Workplace incivility was rated by supervisor with a 7-item scale from Blau and Andersson (2005). The lead-in phrase was “How often have this person exhibited the following behaviors in the past year to someone at work (e.g. co-worker, other employees, supervisor)?”. A sample item reads “Addressed someone in unprofessional terms either publicly or privately” (1 = “never”, 5 = “many times”).

Analytic strategy

This study adopted path analysis in Mplus 7.4 to test the hypothesized model. This approach allowed researchers to integrate tests of mediation and moderation simultaneously using a bootstrap** methodology (Heck & Thomas, 2020). Hypotheses were tested via two steps. First, this study examined the mediating effect (H1 & H2) by calculating 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of the bootstrap simulation (5000 iterations). Second, this study centered workaholism and SSG to estimate the moderating effects of SSG (H3a & H4a) and the conditional indirect effect (H3b & H4b) with 95% confidence intervals of bootstrap** approach (5000 iterations) (Preacher et al., 2010).

Results

This research conducted confirmatory factor analyses to assess whether the scale measures have eligible discriminant validity. The results in Table 5 indicated that our five-factor model provided a significantly better fit than other four alternative models (χ2 = 864.428, df = 395, χ2/df = 2.19, CFI = 0.914, TLI = 0.906, RMSEA = 0.056), which supports the distinctiveness of key variables in this study.

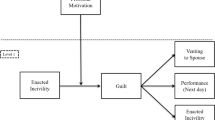

Table 6 provides the descriptive statistics, reliabilities, and inter-correlations of the variables. Consistent with our hypotheses, workaholism was positively related to emotional exhaustion (r = 0.200, p < 0.01) and psychological entitlement (r = 0.457, p < 0.001). In addition, emotional exhaustion and psychological entitlement respectively have a positive correlation with workplace incivility (r = 0.211, p < 0.001; r = 0.373, p < 0.001). Hypotheses testing. In order to estimate the hypothesized model, this study included focal participants’ gender, age, education, and work tenure as control variables with fixed effects on workplace incivility. The path analysis results were shown in Fig. 2.

H1 argued that emotional exhaustion mediates the relationship between workaholism and workplace incivility. Results in Fig. 2 showed that workaholism positively related to emotional exhaustion (γ = 0.227, p < 0.001), and emotional exhaustion positively related to workplace incivility (γ = 0.213, p < 0.01). The bootstrap simulation results indicated that there was a positive indirect relationship between workaholism and workplace incivility via emotional exhaustion (indirect effect = 0.052, SE = 0.021, 95% CI [0.020, 0.104]). Hence, H1 received support.

H2 suggested that psychological entitlement mediates the linkage between workaholism and workplace incivility. Results in Fig. 2 showed that workaholism has a positive significant effect on psychological entitlement (γ = 0.376, p < 0.001), and psychological entitlement has a positive significant effect on workplace incivility (γ = 0.228, p < 0.001). The bootstrap simulation results suggested that workaholism has a positive indirect effect on workplace incivility via emotional exhaustion (indirect effect = 0.080, SE = 0.029, 95% CI [0.031, 0.144]). Therefore, H2 received support.

H3a stated that SSG moderates the relationship between workaholism and emotional exhaustion. As presented in Fig. 2, SSG negatively and significantly moderates the linkage between workaholism and emotional exhaustion (γ=-0.182, P < 0.05). Thus, H3a received initial support. To better illustrate the moderating effects, we also plotted the interactions according to Aiken and West (1991) (as shown in Fig. 3). In Fig. 3, simple slope analyses suggested that there was a more significantly positive linkage between workaholism and emotional exhaustion when SSG was low (1 SD below the mean: simple slope = 0.343, t = 4.659, p < 0.001) than when SSG was high (1 SD above the mean: simple slope = 0.157, t = 2.338, p < 0.05). Hence, H3a was supported.

H3b proposed that SSG moderates the indirect effects of workaholism on workplace incivility through emotional exhaustion. The results in Table 7 showed that the conditional indirect effect of workaholism on workplace incivility through emotional exhaustion was significantly positive under low SSG (Effect size = 0.082, SE = 0.028, 95% CI [0.037, 0.152]) but was nonsignificant under high SSG (Effect size = 0.022, SE = 0.022, 95% CI [-0.015, 0.073]). The significant difference between the above two conditional indirect effects (Effect size = -0.060, SE = 0.029, 95% CI [-0.131, -0.014]) indicated that SSG plays a critical role in conditioning the indirect effect of workaholism on workplace incivility via emotional exhaustion. Thus, H3b received support.

H4a argued that SSG moderates the linkage between workaholism and psychological entitlement. As presented in Fig. 2, SSG positively and significantly moderates the link between workaholism and psychological entitlement (γ = 0.236, P < 0.01). Thus, H4a received initial support. Our research plotted the interactions to better illustrate the moderating effects (as shown in Fig. 4) (Aiken & West, 1991). In Fig. 4, simple slope analyses revealed that there was a more significantly positive relationship between workaholism and emotional exhaustion when SSG was high (1 SD above the mean: simple slope = 0.438, t = 7.532, p < 0.001) than when SSG was low (1 SD below the mean: simple slope = 0.200, t = 3.474, p < 0.01). As such, H4a was supported.

H4b proposed that SSG moderates the indirect effect of workaholism on workplace incivility via psychological entitlement. The results in Table 7 showed that the conditional indirect effect of workaholism on workplace incivility through psychological entitlement was stronger and significant when SSG was high (Effect size = 0.116, SE = 0.038, 95% CI [0.048, 0.198]) but was weaker and significant when SSG was low (Effect size = 0.044, SE = 0.025, 95% CI [0.007, 0.109]). The significant difference between the above two conditional indirect effects (Effect size = 0.072, SE = 0.030, 95% CI [0.025, 0.144]) indicated that SSG serves a critical role in conditioning the indirect effect of workaholism on workplace incivility via psychological entitlement. Thus, H4b received support.

Discussion

To date, research has not drawn convincing evidence regarding the underlying mechanism between workaholism and workplace incivility. To open this “black box”, our research combined insights from COR theory (Halbesleben et al., 2014) with a moral licensing perspective (Merritt et al., 2010) to systematically examine the underlying mechanism between workaholism and workplace incivility as well as the critical boundary conditions that helps differentiate the above two mechanisms. Findings across two studies suggested that workaholism can impact workplace incivility through the mediating role of both emotional exhaustion and psychological entitlement. Importantly, SSG, on the one hand, serves as critical social resources that neutralize the effect of workaholism on emotional exhaustion and subsequent workplace incivility. On the other hand, SSG serves as contextual cues that magnify the influence of workaholism on psychological entitlement, which in turn is associated with more uncivil behaviors. Next, we discuss the theoretical contributions and practical implications of our findings.

Theoretical contributions

First, our research enriches understanding of the link between workaholism and workplace incivility by elucidating the dual mediating role of emotional exhaustion and psychological entitlement. Drawing on the COR theory, previous research has revealed a positive association between workaholism on workplace incivility. This stream of research emphasizes the depleting nature of workaholism (Clark et al., 2021), contending that excessive time and energy investment in work-related activities by workaholics can diminish their psychological capital, impede work-family enrichment, or increase job stress levels, thereby leading to workplace incivility. However, empirical support for these underlying mechanisms other than psychological capital is lacking (Lanzo et al., 2016; Taheri et al., 2021). Hence, our study first introduces emotional exhaustion, which is triggered by resource loss and represents a primary outcome of COR theory (Lin et al., 2019), as an additional mechanism to existing literature. Besides, our research also highlights psychological entitlement as a novel mechanism to explain the relationship between workaholism and workplace incivility from the moral licensing perspective (Merritt et al., 2010). By doing so, our dual process model addresses the call to investigate more mediators between workaholism and workplace incivility (Taheri et al., 2021), deepening understanding regarding the underlying mechanisms between this linkage.

Second, from a more general perspective, our study contributes to the workaholism literature by revealing the connotation of workaholism more comprehensively. Workaholism consists of the behavioral dimension (working excessively hard) and cognitive dimension (working compulsively) (Schaufeli et al., 2009). However, extant research on the impacts of workaholism mainly focused on the behavioral component by revealing the resources-depleting consequences of workaholism (Balducci et al., 2021; Farasat et al., 2021). In this study, by illuminating the mediating role of psychological entitlement, we highlight workaholism’s cognitive feature of uncontrollable inner drive to work and internal requirements to work beyond reasonably expected standards (Clark et al., 2020; Taris et al., 2010). As such, our study enriches understanding regarding the connotation of workaholism, addressing the call to pay attention to the motives behind workaholism (Clark et al., 2016).

Finally, our study makes contributions by identifying SSG as a critical contingency, which helps differentiate the two mediating mechanisms in our study. Specifically, from the COR perspective, SSG can be seen as important social resources that help reduce workaholism’s resource shortage risks, thus mitigating the influence of workaholism on emotional exhaustion and subsequent workplace incivility. From a moral licensing perspective, SSG can be seen as crucial contextual hints that enhance workaholism’s sense of entitlement, thus heightening the effect of workaholism on psychological entitlement and subsequent workplace incivility. By investigating the moderating role of SSG, our study addresses the calls for exploring more situational factors that influence the effects of workaholism on outcomes (Clark et al., 2016; Taheri et al., 2021).

Practical implications

Our findings also provide two main practical implications. First, organizations should keep vigilant about and try to avoid workaholism, which can lead to workplace incivility via emotional exhaustion and psychological entitlement. For example, organizations can provide training to improve workaholics’ work efficiency, which helps reduce their time and energy depletion in the workplace. In addition, if necessary, organizations need to provide workaholics with psychological intervention to reduce compulsory work and the associated sense of privilege. Moreover, supervisors need to be aware of the benefits and risks of high levels of SSG. From the COR perspective, SSG helps alleviate subordinates’ emotional exhaustion derived from workaholism, thus reducing subsequent uncivil behaviors. From the moral licensing view, SSG, however, magnifies the positive influence of workaholism on subordinates’ workplace incivility via psychological entitlement. Hence, supervisors should pay attention to the potential negative consequences to workaholics’ mental health when offering extra resources and opportunities to them.

Limitations and future research directions

Despite the abovementioned theoretical and practical implications, our research also has several limitations that need to be acknowledged. First, this study could not disentangle voluntary from involuntary workplace incivility. Although the two mechanisms in our study reflect workaholics engaging in uncivil behaviors passively and actively respectively, the adopted workplace incivility measures cannot fully distinguish them. Hence, future research could benefit from making a distinction between active and passive workplace uncivil behaviors. Secondly, although we posit SSG as a unique contingency that moderates the effects of workaholism, our results cannot exclude the possibility that other organizational factors (e.g., organizational resilience) can also affect workaholism’s influence, which is worth further investigation. Finally, although this study used a time-lagged design and collected data from multiple sources, the data in this research are cross-sectional data in essence. Since individuals have daily fluctuations in workaholism (Clark et al., 2021), we encourage future studies to conduct longitudinal studies to better capture the effects of workaholism.

Conclusion

The main purpose of our study is to integrate and expand our understanding of the underlying mechanisms between workaholism and workplace incivility. Based on prior studies, this study introduces emotional exhaustion and psychological entitlement as two dual mediators that link workaholism and workplace incivility. Also, our research highlights SSG as a critical contingency to differentiate these two mechanisms. Given the prevalence of workaholism and workplace incivility in the modern workplace, this research offers practical implications for organizations to establish policies to prevent workaholics’ uncivil behaviors and for supervisors to interact appropriately with subordinates.

Data availability

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

References

Ahmad, M. G., Klotz, A. C., & Bolino, M. C. (2021). Can good followers create unethical leaders? How follower citizenship leads to leader moral licensing and unethical behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 106(9), 1374–1390. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000839

Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage.

Andersson, L. M., & Pearson, C. M. (1999). Tit for tat? The spiraling effect of incivility in the workplace. Academy of Management Review, 24(3), 452–471. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1999.2202131

Balducci, C., Avanzi, L., & Fraccaroli, F. (2018). The individual costs of workaholism: An analysis based on multisource and prospective data. Journal of Management, 44(7), 2961–2986. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206316658348

Balducci, C., Alessandri, G., Zaniboni, S., Avanzi, L., & Fraccaroli, F. (2021). The impact of workaholism on day-level workload and emotional exhaustion, and on longer-term job performance. Work and Stress, 35(1), 6–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2020.1735569

Banks, G. C., Whelpley, C. E., Oh, I. S., & Shin, K. (2012). How) are emotionally exhausted employees harmful? International Journal of Stress Management, 19(3), 198–216. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029249

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173

Blau, G., & Andersson, L. (2005). Testing a measure of instigated workplace incivility. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 78(4), 595–614. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317905X26822

Brislin, R. W. (1983). Cross-cultural research in psychology. Annual Review of Psychology, 34(1), 363–400. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ps.34.020183.002051

Campbell, W. K., Bonacci, A. M., Shelton, J., Exline, J. J., & Bushman, B. J. (2004). Psychological entitlement: Interpersonal consequences and validation of a self-report measure. Journal of Personality Assessment, 83(1), 29–45. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa8301_04

Cheung, M. F., & Wu, W. (2011). Participatory management and employee work outcomes: The moderating role of supervisor–subordinate guanxi. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 49(3), 344–364. https://doi.org/10.1177/1038411111413528

Cheung, M. F., Wu, W. P., Chan, A. K., & Wong, M. M. (2009). Supervisor–subordinate guanxi and employee work outcomes: The mediating role of job satisfaction. Journal of Business Ethics, 88(Suppl 1), 77–89. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-008-9830-0

Chris, A. C., Provencher, Y., Fogg, C., Thompson, S. C., Cole, A. L., Okaka, O., Bosco, F. A., & González-Morales, M. G. (2022). A meta-analysis of experienced incivility and its correlates: Exploring the dual path model of experienced workplace incivility. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 27(3), 317–338. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000326

Clark, M. A., Michel, J. S., Zhdanova, L., Pui, S. Y., & Baltes, B. B. (2016). All work and no play? A meta-analytic examination of the correlates and outcomes of workaholism. Journal of Management, 42(7), 1836–1873. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206314522301

Clark, M. A., Smith, R. W., & Haynes, N. J. (2020). The multidimensional workaholism scale: Linking the conceptualization and measurement of workaholism. Journal of Applied Psychology, 105(11), 1281–1307. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000484

Clark, M. A., Hunter, E. M., & Carlson, D. S. (2021). Hidden costs of anticipated workload for individuals and partners: Exploring the role of daily fluctuations in workaholism. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 26(5), 393–404. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000284

Di Stefano, G., & Gaudiino, M. (2019). Workaholism and work engagement: How are they similar? How are they different? A systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Work & Organizational Psychology, 28(3), 329–347. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2019.1590337

Dionisi, A. M., & Barling, J. (2019). What happens at home does not stay at home: The role of family and romantic partner conflict in destructive leadership. Stress and Health, 35(3), 304–317. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.2858

Fan, X. L., Wang, Q. Q., Liu, J., Liu, C., & Cai, T. (2020). Why do supervisors abuse subordinates? Effects of team performance, regulatory focus, and emotional exhaustion. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 93(3), 605–628. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12307

Farasat, M., Azam, A., & Hassan, H. (2021). Supervisor bottom-line mentality, workaholism, and workplace cheating behavior: The moderating effect of employee entitlement. Ethics & Behavior, 31(8), 589–603. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508422.2020.1835483

Geurts, S. A., & Sonnentag, S. (2006). Recovery as an explanatory mechanism in the relation between acute stress reactions and chronic health impairment. Scandinavian Journal of Work Environment & Health, 32(6), 482–492. https://doi.org/10.2307/40967600

Greenbaum, R. L., Mawritz, M. B., & Eissa, G. (2012). Bottom-line mentality as an antecedent of social undermining and the moderating roles of core self-evaluations and conscientiousness. Journal of Applied Psychology, 97(2), 343–359. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025217

Grubbs, J. B., & Exline, J. J. (2016). Trait entitlement: A cognitive-personality source of vulnerability to psychological distress. Psychological Bulletin, 142(11), 1204–1226. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000063

Guan, X., & Frenkel, S. J. (2019). Explaining supervisor–subordinate guanxi and subordinate performance through a conservation of resources lens. Human Relations, 72(1), 1752–1775. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726718813718

Halbesleben, J. R. B., Neveu, J. P., Paustian-Underdahl, S. C., & Westman, M. (2014). Getting to the COR: Understanding the role of resources in conservation of resources theory. Journal of Management, 40(5), 1334–1364. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206314527130

Han, S., Harold, C. M., Oh, I. S., Kim, J. K., & Agolli, A. (2022). A meta-analysis integrating 20 years of workplace incivility research: Antecedents, consequences, and boundary conditions. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 43(3), 497–523. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2568

Harold, C. M., & Holtz, B. C. (2015). The effects of passive leadership on workplace incivility. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 36(1), 16–38. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1926

Hayes, A. F. (2015). An index and test of linear moderated mediation. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 50(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273171.2014.962683

Heck, R. H., & Thomas, S. L. (2020). An introduction to multilevel modeling techniques: MLM and SEM approaches. Routledge.

Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist, 44(3), 513–524. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.44.3.513

Khan, J., Saeed, I., Ali, A., & Nisar, H. G. (2021). The mediating role of emotional exhaustion in the relationship between abusive supervision and employee cyberloafing behaviour. Journal of Management and Research, 8(1), 160–178. https://doi.org/10.29145/jmr/81/080107

Lam, C. K., Walter, F., & Huang, X. (2017). Supervisors’ emotional exhaustion and abusive supervision: The moderating roles of perceived subordinate performance and supervisor self-monitoring. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 38(8), 1151–1166. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2193

Lanzo, L., Aziz, S., & Wuensch, K. (2016). Workaholism and incivility: Stress and psychological capital’s role. International Journal of Workplace Health Management, 9(2), 165–183. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJWHM-08-2015-0051

Law, K. S., Wong, C. S., Wang, D., & Wang, L. (2000). Effect of supervisor–subordinate guanxi on supervisory decisions in China: An empirical investigation. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 11(4), 751–765. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585190050075105

Lee, A., Schwarz, G., Newman, A., & Legood, A. (2019). Investigating when and why psychological entitlement predicts unethical pro-organizational behavior. Journal of Business Ethics, 154, 109–126. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3456-z

Li, J., Shi, W., Connelly, B. L., Yi, X., & Qin, X. (2022). CEO awards and financial misconduct. Journal of Management, 48(2), 380–409. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206320921

Lin, S. H. J., Ma, J., & Johnson, R. E. (2016). When ethical leader behavior breaks bad: How ethical leader behavior can turn abusive via ego depletion and moral licensing. Journal of Applied Psychology, 101(6), 815–830. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000098

Lin, S. H., Scott, B. A., & Matta, F. K. (2019). The dark side of transformational leader behaviors for leaders themselves: A conservation of resources perspective. Academy of Management Journal, 62(5), 1556–1582. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2016.1255

Loi, T. I., Kuhn, K. M., Sahaym, A., Butterfield, K. D., & Tripp, T. M. (2020). From hel** hands to harmful acts: When and how employee volunteering promotes workplace deviance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 105(9), 944–958. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000477

Merritt, A. C., Effron, D. A., & Monin, B. (2010). Moral self-licensing: When being good frees us to be bad. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 4(5), 344–357. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2010.00263.x

Miao, C., Qian, S., Banks, G. C., & Seers, A. (2020). Supervisor-subordinate guanxi: A meta-analytic review and future research agenda. Human Resource Management Review, 30(2), 100702. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2019.100702

Ni, X., Zhu, X., Bian, W., Li, J., Pan, C., & Pan, C. (2024). How does leader career calling stimulate employee career growth? The role of career crafting and supervisor–subordinate guanxi. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 45(1), 21–34. https://doi.org/10.1108/LODJ-07-2023-0400

Nisan, M. (1991). The moral balance model: Theory and research extending our understanding of moral choice and deviation. In W. M. Kurtines, & J. L. Gewirtz (Eds.), Handbook of moral behavior and development (pp. 213–249). MIT Press.

Oates, W. E. (1971). Confessions of a workaholic: The facts about work addiction. World Publishing Company.

Ogunfowora, B. T., Nguyen, V. Q., Steel, P., & Hwang, C. C. (2022). A meta-analytic investigation of the antecedents, theoretical correlates, and consequences of moral disengagement at work. Journal of Applied Psychology, 107(5), 746–775. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000912

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

Polman, E., Pettit, N. C., & Wiesenfeld, B. M. (2013). Effects of wrongdoer status on moral licensing. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 49(4), 614–623. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2013.03.012

Preacher, K. J., Zyphur, M. J., & Zhang, Z. (2010). A general multilevel SEM framework for assessing multilevel mediation. Psychological Methods, 15(3), 209–233. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020141

Qin, X., Huang, M., Johnson, R. E., Hu, Q., & Ju, D. (2018). The short-lived benefits of abusive supervisory behavior for actors: An investigation of recovery and work engagement. Academy of Management Journal, 61(5), 1951–1975. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2016.1325

Qin, X., Chen, C., Yam, K. C., Huang, M., & Ju, D. (2020). The double-edged sword of leader humility: Investigating when and why leader humility promotes versus inhibits subordinate deviance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 105(7), 693–712. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000456

Rafique, M. (2023). Supervisor role overload and emotional exhaustion as antecedents of supervisor incivility: The role of time consciousness. Journal of Management & Organization, 29(3), 481–503. https://doi.org/10.1017/jmo.2022.39

Robinson, B. E. (1999). The work addiction risk test: Development of a tentative measure of workaholism. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 88(1), 199–210. https://doi.org/10.2466/pms.1999.88.1.199

Sachdeva, S., Iliev, R., & Medin, D. L. (2009). Sinning saints and saintly sinners: The paradox of moral self-regulation. Psychological Science, 20(4), 523–528. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02326.x

Schaufeli, W. B., Leiter, M. P., Maslach, C., & Jackson, S. E. (1996). The Maslach Burnout Inventory-General Survey. In C. Maslach, S. E. Jackson, & M. P. Leiter (Eds.), MBI Manual (3rd ed.). Consulting Psychologists.

Schaufeli, W. B., Shimazu, A., & Taris, T. W. (2009). Being driven to work excessively hard: The evaluation of a two-factor measure of workaholism in the Netherlands and Japan. Cross-cultural Research, 43(4), 320–348. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069397109337239

Spagnoli, P., Kovalchuk, L. S., Aiello, M. S., & Rice, K. G. (2021). The predictive role of perfectionism on heavy work investment: A two-waves cross-lagged panel study. Personality and Individual Differences, 173, 110632. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2021.110632

Spence, J. T., & Robbins, A. S. (1992). Workaholism: Definition, measurement, and preliminary results. Journal of Personality Assessment, 58(1), 160–178. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa5801_15

Stein, M., Schuemann, M., & Vincent-Hoeper, S. (2021). A conservation of resources view of the relationship between transformational leadership and emotional exhaustion: The role of extra effort and psychological detachment. Work & Stress, 35(3), 241–261. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2020.1832610

Taheri, F., Asarian, M., & Shahhosseini, P. (2021). Workaholism and workplace incivility: The role of work–family enrichment. Management Decision, 59(2), 372–389. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-08-2019-1035

Taris, T. W., & de Jonge, J. (2024). Workaholism: Taking stock and looking Forward. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 11, 113–138. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-111821-035514

Taris, T. W., Beek, I., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2010). Why do perfectionists have a higher burnout risk than others? The meditational effect of workaholism. Romanian Journal of Applied Psychology, 12(1), 1–7. https://lirias.kuleuven.be/handle/123456789/486841

Thau, S., & Mitchell, M. S. (2010). Self-gain or self-regulation impairment? Tests of competing explanations of the supervisor abuse and employee deviance relationship through perceptions of distributive justice. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95(6), 1009–1031. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020540

Van Beek, I., Hu, Q., Schaufeli, W. B., Taris, T. W., & Schreurs, B. H. (2012). For fun, love, or money: What drives workaholic, engaged, and burned-out employees at work? Applied Psychology, 61(1), 30–55. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2011.00454.x

Watkins, M. B., Ren, R., Umphress, E. E., Boswell, W. R., Triana, M. C., & Zardkoohi, A. (2014). Compassion organizing: Employees’ satisfaction with corporate philanthropic disaster response and reduced job strain. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 88(2), 436–458. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12088

Wong, Y. T., Ngo, H. Y., & Wong, C. S. (2003). Antecedents and outcomes of employees’ trust in Chinese joint ventures. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 20, 481–499. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026391009543

Wu, X., & Ma, F. (2023). How perceived overqualification affects radical creativity: The moderating role of supervisor-subordinate guanxi. Current Psychology, 42(29), 25127–25141. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03561-6

Xu, X., Peng, Y., Ma, J., & Jalil, D. (2023). Does working hard really pay off? Testing the temporal ordering between workaholism and job performance. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, in press. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12441

Yam, K. C., Klotz, A. C., He, W., & Reynolds, S. J. (2017). From good soldiers to psychologically entitled: Examining when and why citizenship behavior leads to deviance. Academy of Management Journal, 60(1), 373–396. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2014.0234

Zhang, Y., & Du, S. (2023). Moral cleansing or moral licensing? A study of unethical pro-organizational behavior’s differentiating effects. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 40(3), 1075–1092. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-022-09807-y

Zhang, J., & Gill, C. (2019). Leader–follower guanxi: An invisible hand of cronyism in Chinese management. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 57(3), 322–344. https://doi.org/10.1111/1744-7941.12191

Zhang, L., Deng, Y., Zhang, X., & Hu, E. (2016). Why do Chinese employees build supervisor-subordinate guanxi? A motivational analysis. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 33, 617–648. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-015-9430-3

Zhong, J., Zhang, L., & Xu, G. (2022). Is supervisor-subordinate Guanxi always good for subordinate commitment toward organizations? An inverted U-shaped perspective. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 43(4), 517–532. https://doi.org/10.1108/LODJ-06-2021-0292

Funding

This research was supported by the Huaqiao University’s Academic Project Supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (22KGC-QG01), High-level Talents Research Initiation Project of Huaqiao University (21SKBS021), National Natural Science Foundation of China (72,172,048, 72,272,057).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Academic Ethics Committee of Huaqiao University and conducted in line with Helsinki Declaration principles. We used only standard procedures and measurement instruments. With the assistance of internal coordinators (human resource personnel), we first made clear to participants the scientific research purpose only and the confidentiality of our survey. All participants filled in a written informed consent form, claimed their understanding of the study purposes and that they would like to participate in the study voluntarily. After completion, participants were instructed to return the survey directly to the researchers, in closed envelopes.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, X., He, P. & Jiang, S. Workaholism and workplace incivility: a moderated dual-process model. Curr Psychol 43, 21057–21071 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-05946-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-05946-1