Abstract

The present study aims to expand the existing research by uncovering the overlooked role of situational factors in sha** employee perceived shared leadership. To further advance this field of research, our study introduces a novel situational phenomenon called perceived institutional empowerment. Based on social information processing theory and adaptive leadership theory, we assume that perceived institutional empowerment may have a positive impact on perceived shared leadership via a chain mediating mechanism of perceived organizational support (POS) and psychological safety. Using a sample of 302 participants from a large Chinese service company, the hypotheses were successfully validated. Theoretical and practical implications are discussed in our study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

With organizations increasingly moving towards flatter structures to develop, researchers have paid great attention on informal leadership (Marion et al., 2016; Wellman et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2020). Shared leadership, a special type of informal leadership, is regarded as an emergent leadership style that results from the distribution of leadership influence across multiple team members (Carson et al., 2007; D’Innocenzo et al., 2016). Accumulated evidence indicates that shared leadership is of great importance in improving management innovation (Mitchell & Boyle, 2021), creativity (Ali et al., 2020; Gu et al., 2018), and individual learning (Liu et al., 2014). In particular, some studies have found that shared leadership has a more important impact than vertical formal leadership in facilitating group performance (Ensley et al., 2006; Nicolaides et al., 2014). Given the importance of shared leadership, it is crucial to explore ways to enhance employee engagement in this leadership style. Perceived shared leadership reflects an individual’s perception of the extent to which group members engage in shared leadership. In the following, we will use the term of perceived shared leadership to explore its antecedent mechanisms.

So far, researchers have identified employees’ trait (Kalish & Luria, 2021; Pan et al., 2018), ability (Côté et al., 2010), motivation (Badura et al., 2020; Wellman et al., 2019) as predominant antecedents of perceived shared leadership. These studies are mainly built on the assumption that leadership is linked to power, reputation, and status (Campbell et al., 2002; Tost et al., 2013), and that employee is eager to become informal leader (Anderson et al., 2015). As a result, these studies primarily focus on the role of internal factors in sha** perceived shared leadership. However, research suggests that leadership is a volitional behavior that involves personal choices and decisions, which is influenced not only by internal factors such as ability and motivation, but also by external situational factors such as situation (Zhang et al., 2020). For instance, even though employees have strong leadership capabilities and high motivation to lead, they are unwilling to be informal leaders when they perceive that the environment is full of risks. Hence, exploring the role of external situational factors in promoting employee perceived shared leadership is crucial and necessary.

To advance this field of research, the present study introduces a new phenomenon, institutional empowerment, to explain how to enhance the perceived shared leadership from the situational perspective. Institutional empowerment is put forward based on leader empowerment, which can be described as “a series of practices implemented by relying on the organizational institution, which involves delegating responsibilities down the hierarchy so as to give employees increased decision-making authority in executing of their primary work tasks” (cf. Leach et al., 2003, p. 28). Unlike leader empowerment, institutional empowerment enables all employees within the organization to acquire decision-making power regardless of whether leaders are willing to delegate. More importantly, institutional empowerment can shift power from vertical hierarchies to horizontal levels, enabling all members to have opportunities to assume leadership roles. Perceived institutional empowerment reflects employees’ subjective perception regarding the decision-making and autonomy power granted by the organizational institution. When employees perceive that they have been granted more decision-making and autonomy power by the institution, they feel be trusted and thus become more proactive, which is important for enhancing the perceived shared leadership (Badura et al., 2020; Klasmeier & Rowold, 2020).

To further explore how perceived institutional empowerment affects perceived shared leadership, our study introduces two vital internal psychological resources as mediating variables: perceived organizational support (POS) and psychological safety. We draw upon social information processing theory and adaptive leadership theory as the foundation for our research model (see Fig. 1). The present study makes several contributions to the related literature. First, our study proposes a novel empowerment phenomenon, called institutional empowerment, which broadens the scope of empowerment. Perceived institutional empowerment, as a subjective perception, further enriches the understanding of empowerment. Second, our study contributes to the existing literature by revealing the overlooked role of the situational factor (i.e., perceived institutional empowerment) in sha** employee perceived shared leadership. Research indicates that an individual’s decision to serve as an informal leader is influenced by internal and external factors (Kalish & Luria, 2021; Zhang et al., 2020). While prior studies have extensively investigated internal factors such as ability and motivational factors, our study highlights perceived institutional empowerment as a situational cue in sha** employee perceived shared leadership. Last, our study provides a novel perspective for exploring the mechanism through which perceived institutional empowerment affects employee perceived shared leadership. Drawing on social information processing theory and adaptive leadership theory, our study uncovers the chain mediating role of POS and psychological safety in the relationship between perceived institutional empowerment and perceived shared leadership.

Theory and hypotheses

Institutional empowerment

Empowerment is a classic research theme in the organizational behavior and human resources management field. Regarding empowerment, one view is rooted in the organization’s situation. It describes empowerment as “a practice or set of practices that involve the delegation of responsibilities down the hierarchy to give employees increased decision-making authority to execute their work tasks” (Leach et al., 2003, p. 28). Subsequently, studies combine empowerment with leadership and put forward a special type of leadership behavior—leadership empowerment behavior (Ahearne et al., 2005; Kark et al., 2003). Accumulated research has highlighted the importance of leadership empowerment behavior in promoting team and individual output (Cheong et al., 2019; Lee et al., 2018). However, leadership empowerment behavior only occurs in the team. Moreover, not all team leaders are willing to delegate authority to their subordinates. Therefore, organizational practice urgently needs an effective way of empowerment to ensure full delegation to all team members.

Institutional empowerment is a new form of empowerment proposed in this study, which emphasizes that empowerment emerges from the organizational institution. DiMaggio and Powell’s (1983) institutional theory holds that the institution is a key component of the environment, which can exert isomorphism effects on the organization and ensure consistency in the organization’s behaviors under the unified institution. Specifically, the institution stipulates what the organization should do and how to do it and thus plays a critical role in guiding organizational behavior. Institutional empowerment proposed in this study fully combines organizational institution and empowerment, emphasizing two key points: empowerment source and empowerment content. The former is determined by the organizational institution, whereas the latter is consistent with traditional empowerment. Referring to the content of leadership empowerment behavior, in this study, we propose that institutional empowerment includes four components: (a) improving the meaningfulness of work through the institution, (b) providing autonomy from bureaucratic constraints through the institution, (c) promoting participation in decision-making through the institution, and (d) expressing confidence in high performance through the institution (cf. Ahearne et al., 2005). Unlike leadership empowerment behavior, institutional empowerment is expected to apply to all teams within the organization. Specifically, institutional empowerment enables employees of all teams in the organization to acquire decision-making power regardless of whether their team leaders are willing to delegate such power.

Perceived institutional empowerment and perceived shared leadership

Although empirical studies have found that shared leadership can bring many benefits to the organization, employees do not perceive high levels of shared leadership. This lack of perception is related to the informal characteristics of shared leadership (Zhang et al., 2020). According to Morgeson et al. (2010), shared leadership is an informal leadership enacted by employees who are not designated as a formal leader. Compared with formal leader, informal leaders lack a legalized role identity (Zhu et al., 2019), which makes employees hesitant to implement informal leadership due to potential risks such as punishment or rejection by leaders. Chiu et al. (2016) pointed out that legalizing employees’ leadership claiming and maintaining behaviors is an important prerequisite for informal shared leadership to emerge. Therefore, to enhance employees’ perception of shared leadership, the key issue is to enable employees to conduct informal leadership behaviors legitimately.

Based on social information processing theory, we propose that perceived institutional empowerment can enhance employees’ perceived shared leadership by legalizing leadership enacting behaviors. Social information processing theory suggests that individuals rely on environmental cues to interpret workplace events and decide how to develop their attitudes, cognition, and behaviors (Salancik & Pfeffer, 1978). Institutional empowerment measures are designed to help employees by improving the meaningfulness of their work, fostering their participation in the decision-making process, expressing confidence in their high performance, and providing them autonomy from bureaucratic constraints through the institution. These measures provide important information cues for employees that the organization allow and encourage employees to participate in power-sharing. Traditionally, formal leaders are the agents of the organization with absolute dominance and governance authority (Uhl-Bien et al., 2014; Yukl & Van Fleet, 1992). Employees are expected to obey the commands of their formal leaders and not permitted make decisions or take actions on their own. However, institutional empowerment emphasizes that empowerment emerges from the organizational institution, where the institution has a coercive influence (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983). In this sense, institutional empowerment can ensure that the content of empowerment is enforced under the compulsory requirements of the institution regardless of whether the formal leader is willing to delegate. More importantly, institutional empowerment weakens the absolute dominance of the formal leader and makes the power flow from the vertical hierarchy to the horizontal level. As a result, the higher the perceived level of institutional empowerment, the more likely employees are to participate in leadership-sharing, and correspondingly, the higher their perceived level of shared leadership. In line with this discussion, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1

Perceived institutional empowerment positively relates to perceived shared leadership.

The mediating role of perceived organizational support

Adaptive leadership theory indicates that leadership claiming and leadership granting are two typical interpersonal interaction behaviors during the formation of shared leadership (DeRue & Ashford, 2010). Specifically, employees constantly claim their leader identity, while their colleagues consider whether to accept and grant them leader identity and accept themselves as subordinates. If employees stop claiming their leader identity or others are unwilling to grant them leader identity, the position of the informal leader will be altered. In this sense, informal leaders often expend more effort in claiming and maintaining their informal leader status. Consistent with this view, a recent study has shown that both informal leadership claiming and informal status maintaining require considerable resources and effort, and therefore this study emphasizes the importance of supportive resources in preventing energy consumption (Chiu et al., 2021). In summary, providing sufficient supportive resources is key to promoting employees’ perception of shared leadership as it can prevent energy consumption in claiming and maintaining their informal leader status.

POS refers to employees’ general perception regarding the extent to which the organization values their contributions and cares about their well-being (Rhoades et al., 2001). The concept of POS is based on the organizational support theory, which posits that the organization provides valuable resources, such as pay raises and training opportunities, to help employees to replenish their energy (Eisenberger et al., 1986; Rhoades & Eisenberger, 2002). In addition, the theory emphasizes the principles of reciprocity, stating that employees with a high level of POS will strive to repay the organization by hel** it achieve its goals (Eisenberger et al., 2014; Rhoades & Eisenberger, 2002). Shared leadership can inspire employees to work together toward organizational goals (Pearce & Conger, 2003). Therefore, to repay the organization for its support, employees with sufficient energy actively participate in informal leadership claiming and leadership maintaining behaviors to help the organization achieve its goals. Empirical research confirms that employees with higher POS have an increased willingness to claim leadership influence (Klasmeier & Rowold, 2020). Consequently, the higher the level of POS, the more likely employees are to engage in shared leadership behaviors driven by the reciprocity principle, which leads to a higher level of perceived shared leadership.

Given that institutional empowerment is a supportive organizational management practice that can promote POS by creating beneficial working conditions, it is reasonable to assume that perceived institutional empowerment would also be positively related to POS. Specifically, if employees perceive that they have a greater degree of institutional empowerment, such as improving work meaningfulness, providing autonomy from bureaucratic constraints, promoting participation in decision-making, expressing confidence in high performance, they may be more likely to perceive that the organization cares about their well-being and values their contributions. In summary, perceived institutional empowerment enhances employees’ POS by creating favorable working conditions. In turn, employees with high POS are motivated to engage in shared leadership behaviors as a way of reciprocating the organization’s support, which further enhances their perceived level of shared leadership. Therefore, we hypothesize as follows:

Hypothesis 2

POS mediates the positive relationship between perceived institutional empowerment and perceived shared leadership.

The mediating role of psychological safety

Psychological safety is an important intervening mechanism that refers to a belief that one is able to show and express oneself without fear of negative consequence to self-image, status, or careers (Kahn, 1990). With a high level of psychological safety, employees are more likely to seek feedback, express constructive opinions, and discuss solutions to resolve problems (Sherf et al., 2021; Qian et al., 2022). Conversely, a lack of psychological safety can lead employees to perceive the interpersonal environment as threatening and worry about being punished for expressing themselves (Liang et al., 2012). Given the characteristics of psychological safety, we argue that it can elucidate the mechanism through which perceived institutional empowerment affects perceived shared leadership.

Perceived institutional empowerment provides vital environmental cues that organizational institutions allow and encourage employee to actively engage in decision-making. Singh et al. (2013) found that supportive organizational practices are instrumental in sha** employees’ psychological safety. Therefore, perceived institutional empowerment, as a subjective evaluation of organizational practices, not only decreases employees’ psychological concerns (e.g., being punished or excluded) but also increases their willingness to take risks. In short, perceived institutional empowerment contributes to psychological safety.

Psychological safety also plays a critical role in enhancing employee perceived shared leadership. Research suggests that is associated with many benefits for organizational development, yet employees’ perception of shared leadership is still low. One important reason for this is that employees lack psychological safety. Shared leadership means that employee who usually are not the leader share leadership responsibilities (Carson et al., 2007; D’Innocenzo et al., 2016), which can pose a status threat for formal leaders, particularly those who display high levels of authoritarian leadership (Stewart et al., 2017). As a result, formal leaders may take stern measures such as punishment or exclusion to suppress the emergence of shared leadership. These negative feedbacks make employees realize that the environment is unsafe to enact shared leadership. Similar to this view, Zhu et al. (2018) proposed that implementing shared leadership can be difficult and challenge in contexts where authoritarian leadership is dominant, as employees lack psychological safety. Thus, the lack of psychological safety is a key reason that contributes to employees being unwilling to assume informal shared leadership and consequently leads to low perception of shared leadership. In other words, there is a positive relationship between psychological safety and perceived shared leadership. Taking all these aspects together, we assume that psychological safety may serve as a bridge between perceived institutional empowerment and perceived shared leadership. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3

Psychological safety mediates the positive relationship between perceived institutional empowerment and perceived shared leadership.

The chain mediating role of perceived organizational support and psychological safety

As noted above, we further assume that perceived institutional empowerment can enhance employees’ psychological safety by improving POS in the workplace, ultimately enhancing employees’ perception of shared leadership. In other words, we propose that POS and psychological safety play a chain mediating role in the relationship between perceived institutional empowerment and perceived shared leadership.

According to social information processing theory, perceived institutional empowerment releases a series of signals that the organizational institution allows employees to participate in the decision-making process. These favorable organizational policies can significantly promote employees’ POS (Rhoades & Eisenberger, 2002). POS, as an available instrumental resource, can generate a gain spiral effect; in particular, it results in increased intrinsic resources, namely, psychological safety (Singh et al., 2018). An empirical study also suggested that the improvement of POS is of great importance for improving individual psychological safety during the period of COVID-19 (Xu et al., 2022). Consequently, POS is closely related to psychological safety. In situations where there is a high level of psychological safety, employees feel that the environment is safe, which generates a belief that they can take risks to assume leadership responsibility. This ultimately results in a higher perception of participation in shared leadership (DeRue & Ashford, 2010; Klasmeier & Rowold, 2020). Based on the above analysis, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4

POS and psychological safety sequentially mediate the positive relationship between perceived institutional empowerment and perceived shared leadership.

Method

Participants and procedure

We conducted this study in a large comprehensive service company located in northeast China. We chose this firm as the research object for the following reasons: First, this company, which we have tracked for ten years, implemented a series of institutional reforms before we conducted this investigation. Among them, institutional empowerment is one of the most representative reform measures. Second, this is a service company, which integrates hotel service, catering, and leisure tourism. Service-oriented firms face a more complex and changeable business environment. Their profits come from frontline stores, which not only must meet the needs of customers and maintain operational stability but also address emergencies and additional requirements put forward by customers in the shortest time. Therefore, it is necessary to achieve a high degree of autonomy through shared leadership to complete tasks effectively. Based on practical observation and the research purpose, we thought it appropriate to choose this company as the research object.

All data were collected onsite through paper questionnaires. After obtaining permission from the management and human resource departments of the targeted organization, we entrusted the human resources department to distribute the survey to all departments. The purpose and instructions of the survey were presented to participants in detail in writing. To improve data collection quality, all participants were given a school souvenir gift box as a reward. 339 questionnaires were obtained preliminarily. After deleting invalid questionnaires with excessive missing data or repeated answers, the final effective sample size was 302, yielding an effective response rate of 89.09%. All 302 participants were frontline employees from the food and beverage, purchasing, sale, entertainment, logistics, security, front office, housekee**, and management departments. Among them, 157 (51.99%) were female and 145 (48.01%) were male employees. The majority were aged 36 to 45 years (32.50%), and 60.26% had more than five years of work experience.

Measures

Because all the measurement scales we adapted were in English, we used a double-translation procedure to translate them into Chinese (Brislin, 1980). Participants responded to all survey items using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Perceived institutional empowerment

To assess perceived institutional empowerment, we modified Leadership Empowerment Behavior Scale (Ahearne et al., 2005) by changing the words from manager to institution and asked individuals to what extent they experienced the following items. Thus, we used a four-dimensional scale to measure perceived institutional empowerment, including employees’ perceived: (a) enhancement of work meaningfulness (three items, α = 0.92; e.g., “The company’s institution helps me understand the importance of my work to the overall effectiveness of the company”), (b) facilitation of participation in decision-making (three items, α = 0.88; e.g., “The company’s institution allows me to participate in major decisions of the company”), (c) expression of confidence in high performance (three items, α = 0.84; e.g., “The company’s institution believes in my ability to improve even when I make mistakes”), and (d) provision of autonomy from bureaucratic constraints (three items, α = 0.82; e.g., “The company’s institution allows me to do my job my way”). The results of a second-order confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) showed that the four sub-dimensions of perceived institutional empowerment could be aggregated into a single underlying dimension (χ2/df = 4.03, RMSEA = 0.08; CFI = 0.94; TLI = 0.92). Thus, we used the average scores of the four sub-dimensions to reflect perceived institutional empowerment. The Cronbach’s α of the overall construct was 0.90.

Perceived organizational support

POS was measured using an eight-item scale developed by Eisenberger et al. (1986). A sample item is “The organization fails to appreciate any extra effort from me”. The Cronbach’s α of POS was 0.88.

Psychological safety

Psychological safety was measured using a two-item scale developed by May et al. (2004). The scale was formed mainly by using Kahn’s (1990) concept of psychological safety. A sample item is “I am not afraid to express their opinions at work”. The Cronbach’s α of psychological safety was 0.68.

Perceived shared leadership

Perceived shared leadership was measured using a brief 16-item scale developed by Hiller et al. (2006), in which employees rated the extent to which they perceived their team members engaging in shared leadership behaviors. A sample item is “I perceived our team members plan how the work gets done”. The Cronbach’s α of perceived shared leadership was 0.98.

Control variables

Following prior studies on shared leadership, we controlled for participants’ education level and work tenure, because these demographic variables are related to shared leadership (Nicolaides et al., 2014; Wellman et al., 2019). Participants’ education level was coded as follows: 1 = high school degree or below, 2 = junior college degree, 3 = bachelor’s degree, and 4 = master’s degree or higher. Their work tenure was coded as follows: 1 = 5 years or less, 2 = 6–10 years, 3 = 11–15 years, 4 = 16–20 years, and 5 = 21 years or more.

Data analysis

First, preliminary analyses (e.g., descriptive statistics and composite reliability) were implemented through SPSS 22.0. Second, the measurement model was estimated via Amos 21.0 with CFA. Third, SPSS PROCESS Macro (model 6) was used to test the whole proposed model. Model fit was evaluated by using the following criteria: χ2/df < 3.00, CFI ≥ 0.90, TLI ≥ 0.90, and RMSEA ≤ 0.08 (Hu & Bentler, 1999).

Results

Confirmatory factor analysis

Before testing the hypotheses, we conducted a CFA to examine construct validity by using Amos 21.0. As shown in Table 1, compared with the three-factor, two-factor and one-factor models, the four-factor hypothesized model has a significantly better data fitting (χ2/df = 2.84, CFI = 0.96, TLI = 0.94, RMSEA = 0.08). The CFA results demonstrated that our four main variables were distinguishable.

Descriptive statistics

The means, standard deviation, correlations, and variance inflation factor (VIF) of the main variables are presented in Table 2. As expected, perceived institutional empowerment, POS, psychological safety, and perceived shared leadership were all positively correlated. Moreover, we examined VIF, which is a widely applied indicator to detect collinearity (García et al., 2015). If VIF is less than 10, indicating that there is no excessive or serious collinearity. The maximum VIF was 1.56, indicating no potentially confounding collinearity problems among the variables (Hair et al., 1998). These results provided preliminary evidence for the next stage of hypothesis testing.

Mediating effect test

We used model 6 of the PROCESS Macro program developed by Hayes (2017) to test the chain mediating model. After controlling for education level and work tenure, the results of the regression analysis were as follows (see Table 3): perceived institutional empowerment could significantly positively predict perceived shared leadership (β = 0.34, p < 0.001); perceived institutional empowerment was significantly and positively related to POS (β = 0.56, p < 0.001) and psychological safety (β = 0.20, p < 0.01); POS could significantly and positively predict psychological safety (β = 0.34, p < 0.001) and perceived shared leadership (β = 0.26, p < 0.001); and psychological safety could significantly positively predict perceived shared leadership (β = 0.26, p < 0.001).

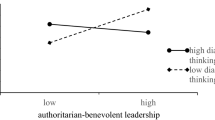

To test the mediating effects, the Bootstrap method was used to calculate the 95% confidence intervals for each of the 5000 repeated samplings. The results of the mediation effect size analysis (see Table 4; Fig. 2) showed that there was a significant indirect path from perceived institutional empowerment to perceived shared leadership through POS (indirect effect coefficient = 0.15, SE = 0.04, 95% CI = [0.08, 0.24]) and through psychological safety (indirect effect coefficient = 0.05, SE = 0.03, 95% CI = [0.01, 0.12]). Furthermore, the indirect path from perceived institutional empowerment to perceived shared leadership through the link “POS → psychological safety” was also significant (indirect effect coefficient = 0.05, SE = 0.02, 95% CI = [0.02, 0.09]). Hence, Hypotheses 1, 2, 3 and 4 were supported.

Discussion

The present study aims to offer deep insights into how perceived institutional empowerment influences employee perceived shared leadership in order to enrich the literature of shared leadership from a situational perspective. Based on social information processing theory and adaptive leadership theory, we propose that perceived institutional empowerment affects perceived shared leadership through the chain mediating mechanism of POS and psychological safety. Specifically, we find that perceived institutional empowerment has a positive direct impact on perceived shared leadership. In addition, the positive effects between perceived institutional empowerment and perceived shared leadership can be realized via the chain mediation effects of POS and psychological safety.

Theoretical contributions

Our study makes several contributions to the literature on empowerment and shared leadership. First, this study combines empowerment with the organizational institution and puts forward the concept of institutional empowerment, which enriches the understanding of empowerment. Traditionally, research on empowerment has mainly focused on leadership empowerment, which holds that leaders delegate autonomy and responsibility to employees (Amundsen & Martinsen, 2014). While the effectiveness of leadership empowerment has been proven, it is noteworthy that leadership empowerment only occurs within the teams they oversee, and not all leaders are willing to delegate authority to their subordinates. Therefore, the institutional empowerment proposed in this study addresses this theoretical limitation. Moreover, as a subjective perception, perceived institutional empowerment further enriches the understanding of empowerment from a cognitive perspective.

Second, this study enriches the understanding of perceived shared leadership by investigating its antecedents from the situational perspective. Previous research has a view that leadership is related to power, reputation, and status (Campbell et al., 2002; Tost et al., 2013), and employees aspire to become informal leaders (Anderson et al., 2015). Consequently, prior studies on the antecedents of perceived shared leadership primarily focused on internal factors such as ability, and motivation, while giving little attention to external situational factors. However, recent research suggests that external situational factors also play a critical role in sha** employees’ decision to implement informal leadership (Zhang et al., 2020). Based on this perspective, our study places greater emphasis on the importance of situational factors in sha** employees’ perceived shared leadership.

Finally, the present study investigates the mechanism by which perceived institutional empowerment promotes employee perceived shared leadership. Based on social information processing theory and adaptive leadership theory, we introduce POS and psychological safety to reveal the influence mechanism. We find that perceived institutional empowerment can enhance perceived shared leadership by the following three ways: (a) by enhancing employees’ POS, they can promptly compensate for the energy consumed during the process of implementing shared leadership, enabling them to continuously participate in leadership-claiming and leadership-maintaining activities; (b) by improving employees’ psychological safety when they engage in informal leadership, thereby making them realize that they are allowed and encouraged to share power; (c) on the basis of (a) and (b), employees’ enhanced POS through perceived institutional empowerment leads to a gain spiral effect, which further activates their psychological safety and ultimately promotes perceived shared leadership.

Managerial implications

Our study provides several implications for management practitioners. First, our study suggest that perceived institutional empowerment increases employees’ perceived shared leadership. To motivate employees to assume leadership responsibility, organizations should focus on improving perceived institutional empowerment. For example, organizations could consider implementing top-down institutional empowerment measures to weaken the absolute dominance of formal leaders and give employees decision-making and self-management power. In addition, considering that institutional empowerment measures can pose a threat to the status of formal leaders, leading to potential resistance to implementing such measures. Therefore, organizations should provide substantial resources and guarantees, such as process design and policy support, to ensure the smooth implementation of institutional empowerment measures.

Second, our study shows that POS acts as a bridge in the relationship between perceived institutional empowerment and perceived shared leadership. Given the importance of POS, organizations should pay closer attention to the needs of their frontline employees and provide them with substantial support, especially if these informal leaders are highly motivated to contribute more. To achieve this, organizations can provide different types of people-oriented support for employees, including psychological support (e.g., organizational trust), material support (e.g., a good salary), and managerial support (e.g., teaching managerial skills or providing more sufficient feedback). Additionally, organizations should consider providing task-oriented support, such as granting informal leaders more autonomy in decision-making and providing them with training. These series of support measures can protect informal leaders from draining their energy. Organizational managers can choose to implement the measures according to their organizational culture.

Third, our research findings also indicate that psychological safety plays a crucial role in linking perceived institutional empowerment with perceived shared leadership. To support employees in taking on leadership responsibilities without fear of punishment, organizations should strive to create a psychologically safe work environment. To achieve this, organizations can develop series of institutional empowerment measures such as encouraging participation in decision-making, improving the meaning of the work, exhibiting confidence in employees, and eliminating bureaucratic obstacles. In addition, it is important to note that psychological safety is fragile and requires constant reinforcement (Joo et al., 2023). Therefore, providing ongoing organizational support is essential for maintaining and strengthening it.

Limitations and future directions

Our study has several limitations, which are worth exploring in future research. First, we tested our model using self-reported measures, which may cause common method bias, although the results showed that there was no obvious common method bias. We encourage researchers to collect data through multiple assessment means and multiple sources to reduce common method bias in future studies. For example, they can assess shared leadership by using the index of network density or decentralization (Carson et al., 2007; DeRue et al., 2015).

Second, while the present study investigates the mediating mechanism of perceived institutional empowerment on perceived shared leadership, it does not explore its boundary conditions. Namely, our study only addresses the questions of whether and how perceived institutional empowerment affects perceived shared leadership, but not consider the question of when the influence occurs. To provide a more comprehensive understanding, we encourage scholars to further explore the boundary of the mediating mechanism to explain when the effects will strengthen or weaken. Prior studies suggest that task characteristics (e.g., task complexity and task interdependence) and cultural characteristics (e.g., power distance and collectivism) are important moderators (Chiu et al., 2016; Zhu et al., 2018). We hope that future research will take these moderators into account.

Third, the reliability of psychological safety in the present study is slightly lower than 0.70, although it is close to the results of previous studies (Liang et al., 2012; May et al., 2004). We speculate that this lower reliability may be related to the number of items on the scale. Although we used a mature scale to measure psychological safety, only two items remained after removing a reverse-scoring item with low factor loading (below 0.30), which result in the lower reliability. Thus, we recommend that future studies use a scale with more items to measure psychological safety in order to improve its reliability.

Finally, we only considered the positive effect of perceived institutional empowerment on perceived shared leadership. Our findings suggest that perceived institutional empowerment positively influences employees’ POS and psychological safety, ultimately enhancing perceived shared leadership. However, it is possible that too much institutional empowerment may result in employees having excessive autonomy and power, which raises more conflict or loss of control. From this perspective, perceived institutional empowerment may not always be beneficial for the emergence of perceived shared leadership. Therefore, we encourage future researchers to investigate the double-edged sword effect of perceived institutional empowerment on perceived shared leadership in the future.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Ahearne, M., Mathieu, J., & Rapp, A. (2005). To empower or not to empower your sales force? An empirical examination of the influence of leadership empowerment behavior on customer satisfaction and performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(5), 945–955. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.90.5.945

Ali, A., Wang, H., & Johnson, R. E. (2020). Empirical analysis of shared leadership promotion and team creativity: An adaptive leadership perspective. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 41(5), 405–423. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2437

Amundsen, S., & Martinsen, Ø. L. (2014). Empowering leadership: Construct clarification, conceptualization, and validation of a new scale. The Leadership Quarterly, 25(3), 487–511. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2013.11.009

Anderson, C., Hildreth, J. A. D., & Howland, L. (2015). Is the desire for status a fundamental human motive? A review of the empirical literature. Psychological Bulletin, 141(3), 574–601. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038781

Badura, K. L., Grijalva, E., Galvin, B. M., Owens, B. P., & Joseph, D. L. (2020). Motivation to lead: A meta-analysis and distal-proximal model of motivation and leadership. Journal of Applied Psychology, 105(4), 331–354. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000439

Brislin, R. W. (1980). Translation and content analysis of oral and written materials (pp. 389–444). Methodology.

Campbell, L., Simpson, J. A., Stewart, M., & Manning, J. G. (2002). The formation of status hierarchies in leaderless groups: The role of male waist-to-hip ratio. Human Nature, 13, 345–362. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12110-002-1019-0

Carson, J. B., Tesluk, P. E., & Marrone, J. A. (2007). Shared leadership in teams: An investigation of antecedent conditions and performance. Academy of Management Journal, 50(5), 1217–1234. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2007.20159921

Cheong, M., Yammarino, F. J., Dionne, S. D., Spain, S. M., & Tsai, C. Y. (2019). A review of the effectiveness of empowering leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 30(1), 34–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2018.08.005

Chiu, C. Y. C., Owens, B. P., & Tesluk, P. E. (2016). Initiating and utilizing shared leadership in teams: The role of leader humility, team proactive personality, and team performance capability. Journal of Applied Psychology, 101(12), 1705–1720. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000159

Chiu, C. Y., Nahrgang, J. D., Bartram, A., Wang, J., & Tesluk, P. E. (2021). Leading the team, but feeling dissatisfied: Investigating informal leaders’ energetic activation and work satisfaction and the supporting role of formal leadership. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 42(4), 527–550. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2511

Côté, S., Lopes, P. N., Salovey, P., & Miners, C. T. (2010). Emotional intelligence and leadership emergence in small groups. The Leadership Quarterly, 21(3), 496–508. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2010.03.012

D’Innocenzo, L., Mathieu, J. E., & Kukenberger, M. R. (2016). A meta-analysis of different forms of shared leadership–team performance relations. Journal of Management, 42(7), 1964–1991. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206314525205

DeRue, D. S., & Ashford, S. J. (2010). Who will lead and who will follow? A social process of leadership identity construction in organizations. Academy of Management Review, 35(4), 627–647. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.35.4.zok627

DeRue, D. S., Nahrgang, J. D., & Ashford, S. J. (2015). Interpersonal perceptions and the emergence of leadership structures in groups: A network perspective. Organization Science, 26(4), 1192–1209. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2014.0963

DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48(2), 147–160. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2095101

Eisenberger, R., Huntington, R., Hutchison, S., & Sowa, D. (1986). Perceived organizational support. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71(3), 500–507. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.71.3.500

Eisenberger, R., Shoss, M. K., Karagonlar, G., Gonzalez-Morales, M. G., Wickham, R. E., & Buffardi, L. C. (2014). The supervisor POS–LMX–subordinate POS chain: Moderation by reciprocation wariness and supervisor’s organizational embodiment. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 35(5), 635–656. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1877

Ensley, M. D., Hmieleski, K. M., & Pearce, C. L. (2006). The importance of vertical and shared leadership within new venture top management teams: Implications for the performance of startups. The Leadership Quarterly, 17(3), 217–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2006.02.002

García, C. B., García, J., López Martín, M. M., & Salmerón, R. (2015). Collinearity: Revisiting the variance inflation factor in ridge regression. Journal of Applied Statistics, 42(3), 648–661. https://doi.org/10.1080/02664763.2014.980789

Gu, J., Chen, Z., Huang, Q., Liu, H., & Huang, S. (2018). A multilevel analysis of the relationship between shared leadership and creativity in inter-organizational teams. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 52(2), 109–126. https://doi.org/10.1002/jocb.135

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E., & Tatham, R. L. (1998). Multivariate data analysis. Uppersaddle River. Multivariate Data Analysis. Upper Saddle River, 5(3), 207–219. 5th ed).

Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Press.

Hiller, N. J., Day, D. V., & Vance, R. J. (2006). Collective enactment of leadership roles and team effectiveness: A field study. The Leadership Quarterly, 17(4), 387–397. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2006.04.004

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Joo, B. K., Yoon, S. K., & Galbraith, D. (2023). The effects of organizational trust and empowering leadership on group conflict: Psychological safety as a mediator. Organization Management Journal, 20(1), 4–16. https://doi.org/10.1108/OMJ-07-2021-1308

Kahn, W. A. (1990). Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Academy of Management Journal, 33(4), 692–724. https://doi.org/10.5465/256287

Kalish, Y., & Luria, G. (2021). Traits and time in leadership emergence: A longitudinal study. The Leadership Quarterly, 32(2), 101443. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2020.101443

Kark, R., Shamir, B., & Chen, G. (2003). The two faces of transformational leadership: Empowerment and dependency. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(2), 246–255. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.2.246

Klasmeier, K. N., & Rowold, J. (2020). A multilevel investigation of predictors and outcomes of shared leadership. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 41(9), 915–930. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2477

Leach, D. J., Wall, T. D., & Jackson, P. R. (2003). The effect of empowerment on job knowledge: An empirical test involving operators of complex technology. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 76(1), 27–52. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317903321208871

Lee, A., Willis, S., & Tian, A. W. (2018). Empowering leadership: A meta-analytic examination of incremental contribution, mediation, and moderation. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 39(3), 306–325. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2220

Liang, J., Farh, C. I., & Farh, J. L. (2012). Psychological antecedents of promotive and prohibitive voice: A two-wave examination. Academy of Management Journal, 55(1), 71–92. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2010.0176

Liu, S., Hu, J., Li, Y., Wang, Z., & Lin, X. (2014). Examining the cross-level relationship between shared leadership and learning in teams: Evidence from China. The Leadership Quarterly, 25(2), 282–295. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2013.08.006

Marion, R., Christiansen, J., Klar, H. W., Schreiber, C., & Erdener, M. A. (2016). Informal leadership, interaction, cliques and productive capacity in organizations: A collectivist analysis. The Leadership Quarterly, 27(2), 242–260. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2016.01.003

May, D. R., Gilson, R. L., & Harter, L. M. (2004). The psychological conditions of meaningfulness, safety and availability and the engagement of the human spirit at work. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 77(1), 11–37. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317904322915892

Mitchell, R., & Boyle, B. (2021). Too many cooks in the kitchen? The contingent curvilinear effect of shared leadership on multidisciplinary healthcare team innovation. Human Resource Management Journal, 31(1), 358–374. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12309

Morgeson, F. P., DeRue, D. S., & Karam, E. P. (2010). Leadership in teams: A functional approach to understanding leadership structures and processes. Journal of Management, 36(1), 5–39. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206309347376

Nicolaides, V. C., LaPort, K. A., Chen, T. R., Tomassetti, A. J., Weis, E. J., Zaccaro, S. J., & Cortina, J. M. (2014). The shared leadership of teams: A meta-analysis of proximal, distal, and moderating relationships. The Leadership Quarterly, 25(5), 923–942. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2014.06.006

Pan, J., Liu, S., Ma, B., & Qu, Z. (2018). How does proactive personality promote creativity? A multilevel examination of the interplay between formal and informal leadership. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 91(4), 852–874. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12221

Pearce, C. L., & Conger, J. A. (2003). Shared leadership: Reframing the hows and whys of leadership. Sage Publications.

Qian, S., Liu, Y., & Chen, Y. (2022). Leader humility as a predictor of employees’ feedback-seeking behavior: The intervening role of psychological safety and job insecurity. Current Psychology, 41, 1348–1360. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-00663-x

Rhoades, L., & Eisenberger, R. (2002). Perceived organizational support: A review of the literature. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(4), 698–714. https://doi.org/10.1037//0021-9010.87.4.698

Rhoades, L., Eisenberger, R., & Armeli, S. (2001). Affective commitment to the organization: The contribution of perceived organizational support. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(5), 825–836. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.5.825

Salancik, G. R., & Pfeffer, J. (1978). A social information processing approach to job attitudes and task design. Administrative Science Quarterly, 23(2), 224–253. https://doi.org/10.2307/2392563

Sherf, E. N., Parke, M. R., & Isaakyan, S. (2021). Distinguishing voice and silence at work: Unique relationships with perceived impact, psychological safety, and burnout. Academy of Management Journal, 64(1), 114–148. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2018.1428

Singh, B., Winkel, D. E., & Selvarajan, T. T. (2013). Managing diversity at work: Does psychological safety hold the key to racial differences in employee performance? Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 86(2), 242–263. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12015

Singh, B., Shaffer, M. A., & Selvarajan, T. (2018). Antecedents of organizational and community embeddedness: The roles of support, psychological safety, and need to belong. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 39(3), 339–354. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2223

Stewart, G. L., Astrove, S. L., Reeves, C. J., Crawford, E. R., & Solimeo, S. L. (2017). Those with the most find it hardest to share: Exploring leader resistance to the implementation of team-based empowerment. Academy of Management Journal, 60(6), 2266–2293. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2015.1173

Tost, L. P., Gino, F., & Larrick, R. P. (2013). When power makes others speechless: The negative impact of leader power on team performance. Academy of Management Journal, 56(5), 1465–1486. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2011.0180

Uhl-Bien, M., Riggio, R. E., Lowe, K. B., & Carsten, M. K. (2014). Followership theory: A review and research agenda. The Leadership Quarterly, 25(1), 83–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2013.11.007

Wellman, N., Newton, D. W., Wang, D., Wei, W., Waldman, D. A., & LePine, J. A. (2019). Meeting the need or falling in line? The effect of laissez-faire formal leaders on informal leadership. Personnel Psychology, 72(3), 337–359. https://doi.org/10.1111/peps.12308

Xu, D., Zhang, N., Bu, X., & He, J. (2022). The effect of perceived organizational support on the work engagement of chinese nurses during the COVID-19: The mediating role of psychological safety. Psychology Health & Medicine, 27(2), 481–487. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2021.1946107

Yukl, G., & Van Fleet, D. D. (1992). Theory and research on leadership in organizations. In M. D. Dunnette, & L. M. Hough (Eds.), Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology (pp. 147–197). Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Zhang, C., Nahrgang, J. D., Ashford, S. J., & DeRue, D. S. (2020). The risky side of leadership: Conceptualizing risk perceptions in informal leadership and investigating the effects of their over-time changes in teams. Organization Science, 31(5), 1138–1158. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2019.1350

Zhu, J., Liao, Z., Yam, K. C., & Johnson, R. E. (2018). Shared leadership: A state-of‐the‐art review and future research agenda. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 39(7), 834–852. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2296

Zhu, F., Wang, L., Sun, M., Sun, X., & Müller, R. (2019). Influencing factors of horizontal leaders’ role identity in projects: A sequential mixed method approach. International Journal of Project Management, 37(4), 582–598. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2019.02.006

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by “the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities” (Grant No. HIT.OCEF.2021021).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Mi, Y., Zhang, X., Liang, L. et al. To share or not to share: How perceived institutional empowerment shapes employee perceived shared leadership. Curr Psychol 43, 4918–4929 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04701-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04701-2