Abstract

Based on the findings of participatory action research conducted in 2020 and 2021 in Karacabey, Bursa (Turkey), the article aims to offer a critical assessment of the current vocabulary that has become prevalent in Migration Studies such as ‘local turn’ and ‘resilience’. In doing so, the article demonstrates the neoliberal logic of governance of migration and integration of migrants and refugees—a logic that is manifested by the Turkish central state in the form of delegating responsibilities to local actors without an attempt to financially strengthen them. Karacabey encounters various problems similar to many other rural and mountainous places in Europe such as depopulation, aging, emigration, deforestation, deinvestment, reduction of agricultural lands and production, and environmental problems. As the last decade has brought about massive migration of Syrians, the article mostly elaborates on their social, economic, and territorial impacts on Karacabey and Bursa—a region that has been historically exposed to various forms of migration, both international and domestic.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Over the past three decades or so, the local municipal level has been a significant point of reference for many scholarly fields (Barber, 2013; Sassen, 1990). The prevalence of local governance in managing large populations across the world corresponds to a kind of ‘local turn’, which has given growing precedence to the cities in general. Migration and refugee studies have also seen a ‘local turn’ that defines municipal actors as the most central actors influential in the management of migration and social cohesion (inter alia, Bendel et al., 2019; Caponio & Borkert, 2010; Caponio et al., 2019; Scholten & Penninx, 2016; Zapata-Barrero et al., 2017). An earlier analysis of the structure of migration and integration governance in the European Union context carried out by Scholten & Penninx, (2016) revealed that there is an increasing dispersal of migration and integration policies over different government levels. While nation-states have handed over power to the European Union (e.g. in immigration regulations, especially to develop a Common European Asylum System), resulting in the Europeanisation and/or regionalisation of migration governance, in integration policy-making, a ‘local turn’ can be noticed instead. While, traditionally, migrant integration was considered a national government task in the EU, as nation-states have specific ideas and path-dependent models about how migrants should integrate, due to the need for pragmatic problem-solving, integration policies evolved at the local level before national integration policies were developed (Scholten & Penninx, 2016). Local authorities and actors take on a double role in migration and integration governance: First, they implement national legislation, and second, they respond to local demands by initiating new policies and practices (Zincone & Caponio, 2006). Hence, local actors have to coordinate with other administrative levels (regional, national, European) as well as a broad variety of actors. Therefore, they play a key role in the processes of integration of migrants (OECD, 2018).

This article addresses the politics and practices of migrant and refugee integration in Karacabey, a rural district of Bursa located in the Marmara region of Turkey and the neighbouring city of Istanbul, from the vantage point of what one could call the politics of subsidiarity. The term refers to the delegation of responsibility for migrant integration from central state actors to local actors. It comprises external conditions, such as various crises or the global impact of neoliberalism underlining resilience, communities, and the internal complexification of immigration and integration politics. Scholten & Penninx, (2016) have shown convincingly that there is a growing complexity of immigration and integration policies being formulated at various levels of government, including the EU and national levels as well as the local and in some cases also the regional level. There is a substantial fragmentation in these policies, imposing the risk of ‘layering’ in a way that may lead to the development of policies at different levels of governance without sufficient strategic and structural connections. Scholten & Penninx, (2016) also reveal that such ‘layering’ leads to a decoupling of policies, resulting in potential policy contradictions and even conflicts between different levels.

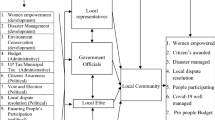

The notion of governance used in this article indicates a new mode of governing that is distinct from the hierarchical control model, a more cooperative mode where state and non-state actors participate in mixed public/private networks (Mayntz, 2003). Hence, migrant integration governance is perceived as a collaborative endeavour to provide migrants with adequate integration measures which involve public (e.g. ministries) and private (e.g. NGOs) collective actors, and operates in a multilevel arena. Needless to say, the ‘cooperative mode’ of governance does not hypostasise any sort of unanimity, or a spirit of solidarity among the actors, but it assumes a more formal mechanism of co-production of policies, rules, and practices. State actors are likely to remain in charge of the reception and protection processes and to delegate the responsibility of integrating migrants to local governments, NGOs, and private individuals through what one could call the politics of subsidiarity (Kaya & Nagel, 2021).

The principle of subsidiarity requires multilevel governance in devolving decision-making to the lowest capable level not only for achieving the tasks required such as integration of migrants and refugees to better engage local bodies, individual actors, and relevant NGOs, but also to preserve strong roles for governments and central state actors in providing direction, standards, guidelines, incentives, and sanctions (Kaya & Nagel, 2021). Multilevel governance was originally defined by Hooghe & Marks, (2001) as the dispersion of authority away from central government—upwards to the supranational level, downwards to subnational jurisdictions, and sideways to the public–private networks. In the field of integration policies, we have seen a distinct shift from the level of the nation-state to the local public–private level. The ‘local turn’ was certainly a necessary shift in the management of migration and integration over the past few decades since the cities have become stronger in taking decisions on many significant problems of their dwellers ranging from the infrastructural necessities to the management of ethno-cultural diversity and social cohesion.

One could also make an alternative reading of this ‘local turn’ and argue that neoliberal forms of governance of nation-states have paved the way to the turn in the making of migrant integration policies and practices. However, these two different interpretations are not mutually exclusive but rather complementary. This article argues that the local turn, which has both empowered and delegated the responsibilities of the central state to municipal authorities as well as to the NGOs, faith-based organisations (FBOs), and private individuals (migrants, refugees, and residents), is a result of neo-liberal forms of governance, at least in the Turkish case. Hence, this article aims to elaborate on the neoliberal face of the local turn in the processes of integration of refugees and migrants in Turkey through the case study of Karacabey, Bursa.

In this article, I will first elaborate on the data collection methods and techniques that are mostly used in the participatory action research (PAR). Following the methodology, the article will be critically engaged in a theoretical discussion on the neoliberal aspects of the terms, ‘local turn’ and ‘resilience’ that have become prevalent in migration and refugee studies. Subsequently, the theoretical debate on such neoliberal aspects will be translated to the Turkish case with the introduction of some religio-political debates on the reception of refugees in Turkey as well as legal discussions in reference to the Municipal Law. To that end, some terms such as community sponsorship, guesthood, Ansar, and fellow citizenship (hemşehrilik) will be discussed in relation to the integration of refugees and migrants at the local level. In what follows, the local case study will be elaborated as far as the challenges, needs, and practices that the research team came across during the participatory action research held in rural places (Karacabey, Bursa) in 2020 and 2021. The article will then focus on the difficulties and precariousness of seasonal and settled Syrian migrants under temporary protection as well as Afghan and Iraqi migrants in the labour market. The discussions on the state of temporality and intersectional forms of discrimination in everyday life will follow. Referring to the testimonies of our interlocutors, the main premise of the article will be that the local turn in the integration of refugees and migrants does not really save them from precariousness since the local actors do not have leverage on making an impact in law and policies.

Methodology

Scientific knowledge is valuable insofar as it expands opportunities for develo** the processes and applications necessary for advancing not only individual well-being but also society as a whole. The idea of collaboration of scientific community members and researchers working together with local individuals and stakeholders to solve problems is necessary for scientific development and social change. Such an approach to knowledge generation is concerned both with changing the lives of individuals and changing the research cultures and institutions (Schneider, 2012). We believe that this is possible with PAR. This is what we tried to do in our field research despite the limitations caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

One of the first scholars who developed participatory action research is Kurt Lewin who was a psychologist working with ethno-cultural minorities in the USA in the 1940s. As someone who originally developed Field Theory, Lewin was one of the scholars who treated psychology as a social science. Lewin demonstrated that research studies with small groups operated most successfully when they were conducted democratically. Based on this democratic, inclusive, and participatory approach, Lewin claimed that research should try to empower and help individuals and social groups to gain self-confidence and self-determination. He argued that allowing individuals to actively engage with research can help them seek independence, equality, and cooperation (Lewin, 1946). PAR proceeds on the premise that there are no generalisable solutions when engaging interlocutors, who are expected to adapt to the changing circumstances and needs in everyday life. Participation is an essential pillar of this approach since ‘action research works on the assumption that all people who affect or are affected, by the issue investigated should be included in the process of inquiry’ (Stringer, 2014, p. 6).

Adopting this approach, we applied different data collection tools/techniques, which are (1) qualitative interviews, (2) participatory observation, and (3) focus groups. Our research team was highly engaged in finding ways to actively involve the participants in the process of research design, conducting the fieldwork, setting up the research agenda, and finding out the challenges, problems, and opportunities of the district as well as different remedies they proposed. We conducted fieldwork in Karacabey and Bursa in 2020 and 2021, following the footprints of participatory action research (Lewin, 1946; McTaggart, 2010; Schneider, 2012; Stringer, 2014). To elaborate on the coexistence of migrant and native communities in Karacabey, depicting the role of central state actors, local municipal actors, civil society actors, and migrants themselves, we conducted 16 semi-structured interviews with migration experts, migrant employees (Syrians), seasonal migrant workers (Syrians and Afghans), small-scale migrant entrepreneurs (Syrians), employers, and local stakeholders involved in health, employment, and education sectors (see Appendix Table 1). The interviews held with migrants were all conducted in rural spaces. Three different sets of questions were originally prepared to be asked to the migration experts, migrants, and local stakeholders.

PAR is not something that is imposed on subjects of research. People are not treated as objects but as autonomous, active, reflexive, responsible, and knowing agents, who work together to achieve change and improvement. Those who are engaged in participatory action research systematically evolve and change. To that end, the practice of selecting the settings for research to happen required a dialogical process in which the research team continually discussed the potential of different organisations, research participants, intermediaries, etc. The kind of questions (e.g. ‘Can you please talk about yourself?’, ‘How do you find the neighbourhood you live in?’) research team members asked in the interviews and their practices of listening to speech acts (Spivak, 2010) removed the research participants (migrants) from the subject status and allowed them to open up and spontaneously illustrate the kinds of internal values they have rather than simply announcing their ethno-cultural, religious, and migrant positionalities. The field researchers’ efforts to listen (Spivak, 2010) allowed research participants to sometimes enact conflicting beliefs they have and negotiate their dilemmatic mix of values during the conversations.

The research team was composed of the principal investigator, researcher, and translator from Arabic to Turkish. Owing to the COVID-19 pandemic, five of the interviews (mostly the ones conducted at national and regional policy levels) had to be carried out online by using the Zoom conferencing tool. After having received the interlocutors’ consent, all of the remote interviews were audio-recorded. Afterwards, they were transcribed verbatim and analysed using thematic analysis. For the remaining face-to-face interviews, the research team used a note-taking technique to communicate better with the interlocutors.

Before the actual participatory action research, the research team paid regular visits to Karacabey to better understand the societal, economic, political, and environmental challenges resulting from the demographic, environmental, political, and societal constraints. During the initial visits to the field as well as the actual field research, we had the opportunity to make participant observations regarding the everyday lives of seasonal migrants, permanent migrants, and residents of the district. Some local actors such as the members of the Migrant Health CentreFootnote 1 accompanied the research team during the site visits to the places where both seasonal and permanent migrants resided.

Another technique we used to collect data was to organise focus group meetings in Karacabey (see Appendix Table 2). Three thematic focus group meetings were organised with the collaboration of our local partner Support to Life (STL) with the specific aim to communicate with local actors and introduce migrant-origin and local community leaders to each other. The participants of the focus groups were selected in such a way that they exhibit a variety of roles at the local level. The roundtable meeting hall of the Karacabey Chamber of Commerce and Industry was selected as a neutral and easy-access location to deter any cost for the participants. Since the focus of the activities was on the impact of migration on the labour markets in rural-mountain regions, selecting the Chamber hall as the event location played a facilitating role in attracting the local stakeholders. The other two focus group meetings were organised with the members of the migrant communities in their habitats. One of them was with the migrant-origin health professionals, and the other was with the seasonal migrants working in the agricultural lands.

Neoliberalism, Local Turn, and Resilience: Responsibilisation of Individuals and Local Actors

Local actors and migrant communities have been increasingly exposed to a discourse of resilience by the post-social states, which have already left their major responsibilities of education, health, security, and pension services to a multitude of specific actors such as individuals, families, communities, local municipal actors, and charities (Inda, 2006, p. 12). The post-social state requires individual actors, families, migrants, local actors, excluded, and subordinated groups who are expected to secure their well-being by themselves. The market is believed to be playing a crucial role in assuring the life of the population concerning the prevention of the risks related to old age, ill health, sickness, poverty, illiteracy, accidents, and so forth. Thus, the rationality of the post-social state, or market state, is extended to all kinds of domains of welfare, security, and health, which were formerly governed by the social and bureaucratic state (Inda, 2006, p. 13). Public provision of welfare and social protection ceases to exist as an indispensable part of governing the well-being of the population. Heteronomous communities of all sorts have become essential in the age of the post-social state because as Inda, (2006) claims the post-social form of governmentality requires the fragmentation of the society into a multitude of communities and the prudentialisms. This implies that individual actors are expected to take proper care of themselves within the framework of existing free market conditions; the social welfare state is no longer there to finance and secure the well-being of the population as the prudent, responsible, self-managing, and ethical political subjects are in charge to take over her role. This is what Inda, (2006) calls the transition from welfarism to prudentialism. Active individual citizens must then be responsible for a variety of risks ranging from the risk of sexually acquired disease to the risk of physical/mental disorder (Rose, 1999, p. 159). This kind of prudentialism can be considered as a technology of governmentality that responsibilises individual actors for their risks of unemployment, health, poverty, security, crime, and so on. Neoliberal governmentality emerges as a form of governance that relies on a generalised praxis of ‘responsibilisation’ (Pyysiäinen et al., 2017). It can be seen as a practice of producing individuals who are responsible for their destinies with the assistance of a variety of private enterprises and independent experts that are the indispensable actors of the free market economy.

In this article, I argue that there is an increasing tendency in migration and refugee studies to translate the prudentialist component of neoliberal governance to ‘resilience’ on the one hand, and the community component to what Tan, (2022) calls ‘refugee protection through community sponsorship’ on the other. As far as the management of mass migrations and integration of migrants/refugees/asylum seekers are concerned, local actors are delegated and responsibilised by the central state actors to take the required steps such as providing migrants and refugees with health services, training opportunities, employment possibilities, housing opportunities, and infrastructural services. It is also a prerequisite for local actors such as municipalities to generate institutional resilience to endure the fact that the central state does not allocate additional financial support to municipal actors to meet the needs of a growing number of refugees in the given local territory. As will be explained shortly, this is the case in Turkey. Neoliberal governance in Turkey under the Justice and Development Party (AKP, Adalet ve Kalkinma Partisi) rule has accommodated various discourses and practices for the management of integration of Syrian migrants under temporary protection as well as other irregular migrants such as Afghanis, Pakistanis, and Iranians, which have so far delegated responsibilities to the municipal actors, NGOs, migrants, and refugees themselves. This is how the ‘local turn’ is operating in Turkey: delegating responsibilities to local actors without any financial assistance from the central state. It is this context where individual local citizens, individual migrants/refugees, local NGOs, and municipal actors are expected to generate resilience to survive (Lewis, 2020; Kaya, 2020).

Resilience has become a popular catchphrase that is being used by governments, international finance organisations, NGOs, community groups, and activists all over the world. Despite its widespread use, there remains confusion over what resilience is and the purpose it serves. Sometimes, resilience may speak to a desire to successfully respond and adapt to disruptions outside of the status quo. However, this conceptualisation of resilience is far from uncontested. Emerging research has shown a lack of consideration for power, agency, and inequality in the popular and academic use of such frameworks. Criticism has also been raised regarding the use of resilience to justify projects informed by neoliberal ideologies aiming to decrease state involvement, increase community self-reliance, and restructure social services (inter alia, Baumgärtel & Miellet, 2022; Cretney, 2014; Joseph, 2013).

The integration systems in many European as well as in non-European countries can only be understood against the backdrop of this neo-liberal turn in the sense that many states have delegated their responsibilities to local actors including the locals, migrants, and refugees themselves. In times of crisis such as war, an epidemic or a natural disaster, the weakened ‘centre’, such as a nation-state or the EU, is likely to ‘escape responsibility’ by delegating crucial tasks to local actors or individual members of the civil society in the periphery (Panizzon & Riemsdijk, 2019, p. 1233). On a semantic level, these developments were closely associated with the increasing popularity of the term ‘resilience’ in everyday life as well as in the fields of migration and refugee studies (e.g. Bourbeau, 2015; Mythen, 2012).

One of the most common definitions of the term was made by Adger, (2000). Accordingly, resilience is the ability to persist, i.e. to absorb shocks and stresses and still maintain the functioning of society and the integrity of ecological systems; it is also the ability to adapt to change, unforeseen circumstances, and risks. Some disciplines, such as psychology and public health, embrace ‘resilience’ as a valuable analytical concept. For instance, resilience literature in the field of public health helps explain the co** mechanisms of individuals and collectives (inter alia see Simich & Andermann, 2014). From a critical perspective though, one may also address the relationality between the prevalent forms of neoliberal governance in everyday life and the growing popularity of the term ‘resilience’. It is important to note that the term ‘resilience’ has also met a lot of criticism for its relevance to a late-modern form of governance. For instance, Chandler, (2014) has criticised the promotion of the term in contemporary scholarship from a Foucauldian perspective, according to which the current forms of neo-liberal governance seek to govern the complexity of everyday life ‘from below’ and to delegate the responsibility for structural problems to the (weakest) individuals and institutions. Other scholars have also explored how resilience has become a defining feature of a neoliberal governmental regime that is progressively shifting from equilibrium to adaptation. Dean, (2014) argues that this shift is a product of a qualitative transformation of neoliberalism. Based on a constant pattern of crises (e.g. financial crisis, refugee crisis, pandemic), poor economic growth, and growing injustice and inequality, neoliberalism seeks to fashion ways to make individuals, communities, migrants, refugees, systems, and institutions fit for rigidities of ‘the catastrophe yet to come’ (Dean, 2014, p. 161). Lately, the COVID-19 pandemic has further legitimised the claim for individual and institutional resilience in everyday life. The notion of resilience thus entails an ultimate acceptance of the view that the world can neither be changed nor mastered; hence, the only rational strategy for survival is to adapt to externally imposed changes (Joseph, 2013; Mavelli, 2017; Walker & Cooper, 2011).

It is necessary to underline the fact that the government and state actors, especially after the loss of metropolitan areas by the ruling party AKP, in the May 2019 local election (Erdoğan et al., 2021), the political discourse of return replaced the discourses of Ansar and hospitality (Rottmann & Kaya, 2020). Since then the ruling party members have refrained from voicing the issue of integration in the public sphere, thus leaving the issue of integration to local actors to a large extent. The radical change in the discourse of the ruling party has also encouraged the other political parties as well as the majority of the public to generate hostile sentiments against the refugees (Aydemir, 2022) leading to further exploitation and precariatisation of the refugees in the labour market. Since then refugees have increasingly become vulnerable because they have been perceived as cheap labour by pro-government small- and mid-sized business circles. Coupled with the growing hostility, mainly initiated by the oppositional parties such as Zafer Partisi against Syrians in particular, and Arabs in general (see Aydemir, 2022), neither religious nor instrumentalist approaches under such circumstances do not help local actors find ways to prevent migrants’ precariatisation. In what follows, first, the migration dynamics of Turkey and Bursa since 2011 will be discussed in general terms; second, the dynamics that lead to the precariatisation of refugees in Karacabey and Bursa will be conveyed to demonstrate that the promotion of both local turn and resilience that highlights the agency of local actors and refugees is not sufficient for refugees to better integrate into their new destinations.

Migrants and Natives in Local Settings: from Community Sponsorship to Fellow Citizenship (Hemşehrilik)

From the onset of the mass migration of Syrians to Turkey in April 2011 to the EU-Turkey Refugee StatementFootnote 2 put into implementation on 18 March 2016, the Turkish state mostly leaned on a religious discourse to accommodate the Syrian migrants under temporary protection: Ansar discourse. Following the implementation of the EU-Turkey refugee statement, local municipalities and other local actors became more involved in the accommodation of the refugees. The attitudes of the municipalities in Turkey towards migrants and refugees demonstrate a great variety. While many municipalities have better performances, there are still others that can be defined as hostile regarding their governance practices (Kaya, 2020; Betts et al., 2021; Memisoglu & Yavcan, 2022). In this section, I will briefly summarise the transformation of migration management from a type of refugee protection through community sponsorship (Tan, 2022) to the delegation of responsibilities to the local municipalities by the Municipal Law (Law No. 5393). Turkish state actors initially perceived the Syrian forced migrants as ‘guests’, with a strong emphasis on the Islamic discourse of Ansar based on the notions of hospitality, benevolence, and temporality.

Community sponsorship has no settled definition, but inherent to the model is shared responsibility between civil society and the state for the admission and/or integration of refugees (Tan, 2022, p. 252). Community sponsorship has been described by the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) as programmes where individuals or groups of individuals come together to provide financial, emotional, and practical support toward the reception and integration of refugees (UNHCR, 2019, p. 8). To this end, there were not only charity organisations in Turkey hel** the refugees but also many rights-based non-governmental organisations were instrumental in absorbing the societal and humanitarian shocks caused by the sudden mass migration of Syrians (Mackreath & Sağnıç, 2017). Hospitality and ‘welcome culture’ towards the refugees over the last decade were visible in many countries including Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, and Turkey from the very beginning of Syrian mass migration. It became more tangible in European countries after the image of the drowned infant Aylan Kurdi shook the West in the summer of 2015 (Smith, 2015).

In both non-EU and EU countries, it was the Qur’anic, Biblical, and theological understandings of guesthood that played an important role among the host communities initially embracing the refugees (Saunders et al., 2016). It was both a political and practical move by many EU citizens who saw the need to protect vulnerable people who were in immediate need. Many EU citizens as well as the Churches opened their arms to asylum-seekers (Chemin & Nagel, 2020). However, this ‘welcome culture’ did not last too long in either the Middle Eastern countries or the EU countries. Across Europe and the Middle East, refugees have encountered several problems in everyday life due to the burgeoning of inhuman conditions in reception centres, long periods of assessing asylum applications, difficulties in the labour market, education and housing facilities, and paternalistic treatment (Kaya & Nagel, 2021).

Traditionally known as an emigration country, Turkey has also become a settlement and transit country for forced migrants. Syrian refugees have been considered ‘guests’ by the Turkish state. At the beginning of their mass migration, Syrian refugees have been presented as if they are ‘welcome’ by the Turkish state and society based on some deep-rooted values such the ‘Turkish hospitality’, ‘Muslim fraternity’, and ‘guesthood’ traditions (Chatty, 2013). However, all these values address that the Syrian refugees have been perceived by the Turkish state actors and society on the basis of temporality (Mencütek et al., 2023).

The most prevalent metaphor to qualify the role that the Turkish state actors played for Syrians in the initial years was the Ansar spirit (Arabic for ‘helpers’). As a metaphor, Ansar refers to the people of Medina who supported the Prophet Mohammad and the accompanying Muslims (muhajirun, or migrants) who migrated there from Mecca, which was under the control of the pagans. The metaphor of Ansar originally points to a temporary situation as the Muslims later returned to Mecca after their forces recaptured the city from the pagans. Hence, the state actors in these four Middle Eastern countries used a kind of Islamic symbolism to legitimise their acts on the resolution of the Syrian refugee crisis. The government leaders consistently compared their role in assisting the Syrian refugees to that of the Ansar, referring to the Medinans who helped Mohammad and his entourage after their forced migration from Mecca to Medina, esca** from the brutality of the paganist Qureshi tribe. Framing the Syrian refugees within the discourse of Ansar has elevated public and private efforts to accommodate Syrian refugees from a humanitarian responsibility to a religious and charity-based duty with the understanding of a kind of community sponsorship (Chatty, 2013; Tan, 2022). The Ansar spirit was visible in Turkey during the first years of the mass migration of Syrians. However, this spirit is now replaced with return discourse to deter newcomers, while the local municipal actors became more engaged in the management of mass migration and integration on the basis of the principle of ‘fellow citizenship’ (hemsehrilik) (Mencütek et al., 2023).

Turkish municipalities follow the principle of fellow citizenship (Hemsehrilik in Turkish), embodied in Article 13 of the Municipal Law,Footnote 3 strive to provide equal services to non-citizen residents, and initiate projects that foster social cohesion between native and migrant communities. The Syrian refugees have been forced to migrate, and most have suffered extreme trauma and impoverishment due to the civil war, and are extremely vulnerable, and face significant challenges, including the language barrier, as they struggle to rebuild their lives and meet their many needs with minimal resources in a foreign country. It is not surprising that their vulnerability and inability to communicate with locals tend to make Syrians introverted (Erdoğan et al., 2021; Rottmann & Kaya, 2020).

Municipalities have so far played a pivotal role in integrating refugees at the local level in Turkey as well as elsewhere (Durmuş, 2022). Municipal responsibilities include ensuring that native and migrant communities coexist in peace, and their role in this is far more important than that of national and international actors (Scholten & Penninx, 2016). Challenges faced by nation-states in realising the 2016 UN Sustainable Development Goals and in managing migration and social cohesion have increased significantly, and they must be also addressed at the local level. Migration studies literature (Durmuş, 2022; Scholten & Penninx, 2016) confirms that this is happening, and Turkish municipalities have played a more active role in this regard, which was given further impetus by the 2016 EU-Turkey Refugee Statement.

The local environment for which municipalities are responsible is where migrants and native populations live, work, interact, use infrastructure and receive services, the availability, and quality of which affect social harmony, inclusion, and coexistence. Turkish Municipal Law includes the principle of ‘fellow citizenship’, and municipalities are responsible for meeting the day-to-day needs of all residents and for promoting a culture of coexistence irrespective of residents having Turkish citizenship. Article 13 of the Turkish Municipal Law states that ‘Everyone is a fellow citizen of the city in which he resides. Fellow citizens shall be entitled to participate in the decisions and services of the municipality, to be informed about municipal activities, and to benefit from the aid of the municipal administration’. This article makes municipalities responsible for improving social and cultural relations among ‘fellow citizens’ and grants equal rights and responsibilities to all, whether legal citizens or not, and it is important that the general public is made aware of this, about coexistence and social cohesion between the native and migrant communities.

However, Article 14 makes an implicit distinction between citizens and non-citizens in the statement ‘Municipal services shall be rendered most appropriately at the places nearest to the citizens’, which appears to be inconsistent with Article 13 which refers to ‘fellow citizens’, defined as all residents. Nevertheless, most municipalities accept and act according to the principle of fellow citizenship in Article 13, rather than trying to avoid their equal responsibilities regarding resident migrants by appealing to Article 14, and a literal interpretation thereof.

Local municipalities in Turkey still lack central-government funding for refugees. Since the amount of the budget allocation from the national budget is indexed to the number of Turkish citizens only, the presence of refugees does not lead to an increase in financial allocation (Betts et al., 2021; Coşkun & Uçar, 2018). On the other hand, refugees do not also contribute to the municipalities’ budgets since they are not subject to paying local taxes (Coşkun & Uçar, 2018). So, the limitation on financial resources becomes a critical issue for those municipalities that host a high number of refugees. A growing number of refugees in many cities increase the demand for infrastructure services such as garbage and wastewater, which need to be compensated for without any extra budget (Coşkun & Uçar, 2018). Furthermore, municipal administrators are also exposed to criticisms from residents who do not feel comfortable with the usage of municipal resources for non-citizens (Kale & Erdoğan, 2019).

The contradiction between these two articles demonstrates that the central state delegates responsibilities to the municipalities while refraining from allocating financial resources to meet the needs of a growing number of residents resulting from the mass migration of incoming refugees. Hence, there is a ‘local turn’ in terms of increasing responsibilities of local municipalities to integrate refugees and a quest for generating ‘resilience’ among the local municipalities, local NGOs, and refugees, while the central state actors have gradually opted for withdrawing themselves from being engaged in integration of refugees at the local level. This may seem rather normal at first glance, but the delegation of responsibilities without the allocation of resources makes it very difficult for local actors to manage the integration of a growing number of refugees. Karacabey is an example that presents such inconsistencies. Analytically, such devolutionary trends can be understood as a function of the proliferation of neoliberal governance (Dobrowolsky, 2013; Filomeno, 2016, p. 4). One of our interlocutors working as an officer in the Bursa Metropolitan Municipality states the following when asked about the role of the central state in managing the integration of Syrian refugees under temporary regulation settled in Bursa:

I don’t think that the Turkish state has a feasible migration policy toward the Syrians and others. Syrian migration has always been politicised in one way or another. So far, the most common discourse raised by the central state actors is as follows ‘Syrians were in a dire situation, and we look after them’. Apart from this charity-based approach, the central state has not really assigned any particular role to neither central state actors nor municipal actors. Our municipality and others have been left alone to find ways to meet the needs of migrants and refugees (Interview, WP3TR004).

All kinds of local actors, be it municipal, NGO, local individuals, or migrants, are expected to be resilient in their code of conduct in everyday life to meet the needs of their districts resulting from the mass migration of refugees in metropolitan cities, towns, and rural places. Local authorities cooperate with civil society organisations to provide free services and orientation to Syrians about education, health services, and training opportunities. To overcome financial constraints, actively engaged municipalities seek external funding through establishing partnerships with NGOs and international actors. In other words, local municipalities have discovered some ‘bypass methods’ to reach extra funds for the welfare of refugees (Betts et al., 2021; Coşkun & Uçar, 2018). Local governments have no legal, financial, or political-administrative responsibility and authority (Sotomayor & Gilbert, 2022). Although they are not active in the formulation and implementation of legal regulations and policies to tackle the refugee issue (Coşkun & Uçar, 2018), and they are not provided by the central state any extra budget to meet the needs of migrants under temporary protection, they are still important actors in the field with responsibilities.

Socio-economic and Spatial Distribution of Migrants and Refugees in Bursa and Karacabey

Historically, Bursa has always been a sanctuary city for many migrants and refugees including Hannibal, the Carthaginian general, and many others to come. Thousands of Turkish-origin and Muslim migrants mainly originating from the Balkans and North Caucasus were settled in Bursa in the late nineteenth century and twentieth century. Migratory inflows to Bursa yielded several positive outcomes: hard-working migrants contributed significantly to the city’s economy, resulting in substantial developments in trade and agriculture, and they enhanced Bursa’s ethno-cultural diversity (Pınar, 2014).

Having vast and fertile plains as well as vast and richly varied forests of the surrounding mountainous region, the geographical location gives the city a special feature of a rare agricultural region along with industrial and trade centres (Ak, (2017)). Bursa’s population in 2021 was 3,101,833. Karacabey is one of its 17 municipalities, with a population of 84,666 as of 2021. Karacabey includes 64 villages in its district. Regarding population per gender, it has a balanced demographic structure, having 50.06% (42,013) male and 49.94% (41,910) female population. The ratio of foreigners to the total population in this district is 3.65% which corresponds to 3063 in numbers. The foreign population figures include the Syrian population (2828 in numbers) under temporary protection, which corresponds to 3.37% of the total population located in Karacabey.

In terms of the economic structure, the district economy in Karacabey is based on the sectors such as agriculture, trade, industry, transportation, and service. Besides, animal husbandry, especially horse and sheep breeding, is also a highly developed sector in the district. As agriculture and animal husbandry have an important place in production, the agriculture-based industry in the district has considerably developed, and the district has been the centre of attraction for important investments. Leading factories operating in the food industry sector (e.g. Nestle, Sütaş) are centred in the district. Those working in the industry and agriculture sector mostly work as seasonal workers (Ak, (2017)).

Despite the historical relevance and potential of Karacabey in terms of being a strategically essential rural centre for the supply of agricultural products, it continues to lose population over the last couple of decades. Depopulation in rural areas is a worldwide problem with its socio-economic and ecological consequences (Tenza-Peral et al., 2022). The lack of structural measures for boosting rural development and providing self-sustaining enterprises that would help rural producers stand on their own feet has resulted in the shrinking of agricultural-based businesses in Turkey (Arıcı & Kirmikil, 2017, p. 39). The lack of laws and policies to boost rural development has dispersed young locals in Karacabey towards the urban centre (Bursa), or to the big cities, especially the neighbouring metropolitan city of Istanbul. This demographic pressure coupled with the fragmentation of inheritances has made the agricultural lands idle for the past two decades (Ak, (2017), p. 235).

Considering its vast agricultural lands, there is a pressing need in agricultural workforce in Karacabey, especially in the summer periods. Agricultural lands in Karacabey are attracting thousands of seasonal workers coming from the southeastern and southern parts of Turkey each year between April and September, some of whom are Turkish citizens and some of whom are Syrians, particularly for the last 10 years. Both seasonal and permanent migrants and refugees meet an urgent need that is the continuation of harvesting fertile agricultural lands, an activity that seems to be neglected by the locals due to the reluctance of young people in taking part in agricultural production, its concomitant growing emigration pattern, and the fragmentation of inheritances.

The lack of support by the central state actors and the municipal actors does not help reversing the process of agricultural decline. The legal regulation changing the status of villages and boundaries of metropolitan municipalities in 2012 under the neoliberal AKP rule has deteriorated even more the issue of allocating enough resources for rural development. The Law on Greater Municipalities (No. 6360) rescaled the urban areas by absorbing rural areas.Footnote 4 Towns and villages have been eliminated along with their legal personality within the boundaries of metropolitan areas; villages have been transformed into neighbourhoods; and the common goods of villages have been transferred to metropolitan municipalities. In addition to the problem of depopulation generating territorial imbalances, this law has posed further hindrance for the peasants and villagers to be productive in agricultural production processes. The main logic behind formulating such a law was to transform agricultural lands into non-agricultural uses and to exploit them for capitalist mode of urbanisation (Arıcı & Kirmikil, 2017, pp. 42–44). The interlocutors and local stakeholders during our research activities raised this issue, an issue that does not help in preventing depopulation. Our interlocutors in Karacabey described incoming migration and seasonal migrants as the most feasible way to curb depopulation and agricultural decline at the time of the research activities.

Bursa is one of the cities most affected by the forced mass migration of Syrians. Bursa has recently attracted thousands of Syrian workers with an expertise on textile production in their home province, Aleppo, to find jobs in the city’s traditionally strong textile sector. According to the official figures, Bursa was home to 181,266 Syrians in September 2021.Footnote 5 Syrians in Bursa mostly arrived in the last few years to benefit from its labour market, housing, health care, and educational opportunities, along with its multicultural environment created by the city’s rich migration history. The majority of Syrians residing in Bursa today are originally from Aleppo. Already existing historical, cultural, and commercial ties between Bursa and Aleppo, especially in the silk and textile industries, make the city a sanctuary for the Syrian migrants (Kaya, 2020).

Based on their proportion among foreign nationals in Bursa, Syrian migrants under temporary protection as well as other migrant workers such as Afghans and Iraqis are the particular focus of the case study. The specific subgroup is represented by the Syrians under temporary protection whose population rate corresponds to more than 5% of the province’s current population. Karacabey hosts around 3000 Syrians under temporary protection out of 225,015 migrants (180,910 Syrians under temporary protection and 48,595 regular migrants with residence permits) in total residing in Bursa as of 19 August 2021.Footnote 6 Karacabey is also a district that stands out with its agricultural production as well as with its industrial facilities based on agricultural production. The interaction between the local citizens living in rural areas and seasonal agricultural migrant workers (mostly Syrians) who live in tent cities built in the surroundings of the district of Karacabey will be amplified in what follows in order to demonstrate the precarious conditions of migrant workers in everyday life that are not appropriately addressed and resolved by the local actors due to their lack of capacity in making an impact on laws and policies at the macro level.

Informality in the Labour Market and Work Permits

As of May 2019, before the COVID-19 pandemic, employment in the informal sector made up 34.3% of the total employment of the Turkish economy. Among those who were employed, the informality rates were 17.1% without Syrians and 20.1% with Syrians. The nationwide informality rates, including self-employed persons, were about 34.34% without Syrians and 36% with Syrians. In certain sectors such as garment, construction, agriculture, food, and beverage services, higher informality rates are observed (Akay & Doğan Yenisey, 2021; Caro, 2020). Bursa and Karacabey are not any different from the rest of Turkey in terms of the prevalence of informal labour market that is far from the reach of local municipal actors due to their incapacity in making impact in laws and policies to curb informality.

During the interviews, several Syrian migrant workers stated that the jobs that were offered for them via labour networks turned out to have poor working conditions as well as low salaries that were oftentimes not paid on time and consistently. Migrants under temporary protection were given in January 2016 a limited formal access to the labour market. According to Article 11 of the Regulation of Work Permits of Foreigners under Temporary Protection issued on 15 January 2016 (No: 29594), associations holding a particular status of ‘associations functioning for the public benefit’ may lodge an application for the employment of foreigners under temporary protection in humanitarian assistance activities.Footnote 7 Article 8 of the same regulation also states that the number of workers under temporary protection cannot be more than 10% of the overall workforce held by the Turkish citizens. Jobs are mostly found in the textile, construction, service, and agricultural sectors in Karacabey and Bursa. Wages for Syrians are generally reported to be only half of the minimum legal salary, and some participants in Karacabey reported making as little as 80 TL a day (equivalent of 8 Euro in August 2021) (Interview WP5TRB009). It should be mentioned of course that none of these jobs provides job security, occupational safety, or social security benefits.

The lack of formal structures at local level to help migrants find jobs has made their integration even more difficult. Many Syrians had to work in underpaid jobs which mostly did not correspond with their qualifications. As the safety net in big cities was not very strong, the difficulties in the labour market even triggered the exploitation of child labour among Syrian families. A 45-year-old Syrian woman, who came to Şanlıurfa in 2012, temporarily working in Karacabey as a seasonal agricultural worker in the summer of 2021, uttered the following words when she was asked about her children:

We came to Şanlıurfa first in 2012 to work in the agricultural sites and green houses. Between April and September, we are coming to Karacabey as seasonal workers to work in the fields to harvest tomatoes, or whatever is offered to us. Our children also work with us. We all get paid the same salary. If the children are too small then one of the elderly children stay with them at the tent. When we are back in Şanlıurfa in September then we work in the fields to harvest apples (Interview WP5TRB010).

Child labour, exploitation of men and women in the labour market, low salaries, lack of social security, difficult working conditions, lack of formal channels to help migrants find jobs, and lack of official controls in the labour market have been repeatedly expressed by our interlocutors. A 48-year-old man from Kobani in northern Syria said the following when asked about their conditions in the labour market:

I was working in agriculture in Syria, and I am doing the same job here. Now we are harvesting tomatoes, and soon we will travel to Mersin to harvest apples. In the winter, we continue to work in the green houses. Our children also have to work with us. We all get the same salary. They cannot g oto school as we are always on the move (Interview WP5TRB011).

Before the enactment of Law 8375 in January 2016, which allowed Syrians under temporary protection to have work permits only under certain conditions and with certain restrictions, there were only 7351 work permits issued to Syrians.Footnote 8 They were mostly issued to those who started a business. The number of Syrians who received work permits in 2019, released by the Ministry of Labour and Social Security, was around 65,000 (see Appendix Table 3).Footnote 9 The number of work permits issued in Bursa in 2019 was 8609. Also, according to data provided by Bursa Provincial Directorate Social Security Institution, as of August 2021, there were 9172 foreigners registered in the Social Security system in Bursa. While 8300 were male, 872 were female. In Karacabey, there were only 37 males registered in the social security scheme and 3 female (see Appendix Charts 1 and 2). Our interviews and observations also affirm this data since there is high informality among the foreigners working in Karacabey.Footnote 10

It is reported that there was no substantial change in this figure during 2020 and 2021 due to the negative impact of COVID-19 pandemic in the labour markets. Syrians living in urban areas have to work to sustain their livelihood, and several hundred thousands have joined the informal workforce. Anecdotal evidence points to a boom in the construction sector arising from the arrival of the refugees, particularly in the provinces bordering Syria, and that textiles and clothing manufacturing, agriculture and service sector were other major sectors of informal employment for refugees (Erdoğan et al., 2021). The field research findings indicate that one of the main reasons for the reluctance of Syrians to apply for work permits is the fact that they knew that they would no longer be able to benefit from financial (e.g. ESSN) and in-kind assistance once they are given a formal work permit.

Turkish labour market has its ongoing chronic structural problems such as high informality, low skill sets of the labour force, and low labour force participation rates of women. Formal jobs are more difficult to secure for the low skilled workers such as the young, the women, and Syrian refugees. Laws and policies to protect migrant populations are in the reach of local actors; they are still under the jurisdiction of the central state actors in Turkey. Delegating the responsibility of employing migrant workforce to the local stakeholders without an attempt to fully formalise their entry to the labour market makes them more vulnerable to exploitation, discrimination, low wages, and long working hours. In terms of discrimination and wage gaps between migrants and nationals, recent research shows that Turkish natives earn 63% more than Syrians (Akay & Doğan Yenisey, 2021; Caro, 2020).

The local business actors in Karacabey try to include the Syrians in the formal labour market despite the bureaucratic inefficiency of the central state actors to do so. For instance, Karacabey Chamber of Commerce and Industry Vocational Training Center provides an opportunity for foreigners in their region to receive occupational training that includes theoretical and practical training. Those graduating from the programme are entitled to obtain vocational high school diploma. However, most of the foreigners such as the Syrians cannot be issued a high school diploma since they cannot demonstrate their secondary school graduation diploma while registering to the school. Hence, such foreigners are only entitled to receive a certificate of attendance. An officer working in the Chamber of Commerce and Industry stated the following when asked about the conditions of foreigners which they cannot resolve at local level:

Vocational training courses offer important opportunities to everyone including immigrants. The Ministry of National Education has given instructions for the registration of immigrants to the courses this year, but the problem is that those who may attend the trainings must be secondary school graduates. Immigrants do not have their graduation certificates with them. As they cannot present their documents, we cannot issue them an occupational school diploma (Interview WP5TRB003).

Vocational training is one of the important ways to close the labour shortage in Karacabey. Our interviews conducted in both regional and local levels also reveal that there is intermediate and technical staff shortage:

There is no such thing as not being able to find a job for qualified personnel in Karacabey. Technical staff can get more salaries than an engineer. No matter a citizen or an immigrant, the firms are dependent on them, so to speak (Interview WP5TRB003).

Despite the fact that there is a growing need for skilled labour in the region—a need that can be partly reciprocated by migrant youth—the local stakeholders are not able to resolve the bureaucratic difficulties without the support of the central state actors.

Temporary Protection Status as a Challenge

In an economy where informality is merely a reflection of the underlying structural problems of the national labour market, it is very difficult to secure formality for migrants in general, and migrants under temporary protection in particular. More than 1.6 million Syrians in Turkey relied on the financial assistance provided by the European Union under the Emergency Social Safety Net (ESSN).Footnote 11 Some argue that the financial aid provided by the EU under the ESSN program is creating an increasingly dependent and passive population of migrants. The Ministry of Labour and Social Services prepared an Exit Strategy from the Social Cohesion Assistance Program for Syrians in 2018 to define strategies for incorporating migrants into social life as active participants, particularly as registered, formal participants in the labour market.Footnote 12 The document recognises that the Syrians under temporary protection are more settled in Turkey (p. 4) and that the Turkish government is willing to ‘implement more development-oriented assistance programs rather than humanitarian assistance. For this reason, a graduation strategy is considered vital for enhancing the skills and competences of the Syrians under temporary protection and making them less dependent on the social assistance’. The strategic purpose of this ‘graduation’ process is identified as ‘to increase the social cohesion of the Syrians under temporary protection by supporting their adaptation to the labour market’ in Turkey (p. 13). However, the COVID-19 pandemic has made it difficult for the Turkish state actors to pursue such a goal.

Syrians under temporary protection in Karacabey and Bursa have also expressed some other concerns regarding the graduation to formality, mainly resulting from the lack of political will of the AKP rule that has always perceived the Syrians as cheap labour source. The difficulties encountered in naturalisation and having work permit are two common impediments expressed by our interlocutors. A 33-year-old businessman who came to Bursa with his family in 2011 when the civil war erupted in Syria has complained about such difficulties. Although he received Turkish citizenship, he stated that citizenship application for the rest of his family is still pending:

We are from Aleppo. We are a wealthy family. We used to do business with Saudi Arabia and other countries before the war… After the war erupted we came here with a lot of money. We invested in a dairy product factory in Karacabey where we employ both Turkish and Syrian workers. We were planning to do export, but because of the depreciation of the TL against the foreign currencies lately, we decided to produce for the domestic market. The COVID-19 pandemic initially affected us badly, but now we are doing fine. I received my Turkish citizenship in 2017. But the rest of the family, my father, brother, uncle could not yet receive citizenship. The workers in my factory received citizenship but my family members could not… I think investors should be given citizenship immediately… (Interview WP5TRB008).

Temporary protection regulation blocks the path for the Syrians to citizenship and access to individual international protection application. For this reason, the Turkish government grants citizenship to Syrians under temporary protection through ‘exceptional citizenship’. Some Syrians are naturalised under the article of exceptional citizenship of the Turkish Citizenship Law introduced in 2009. According to the Article 12 (exceptions in acquiring Turkish citizenship) of this Law (No. 5901), ‘those persons who bring into Turkey industrial facilities or have rendered or believed to render an outstanding service in the social or economic arena or in the fields of science, technology, sports, culture or arts’ can acquire the citizenship.Footnote 13 As of 31 March 2022, Turkey has issued citizenship to around 200 thousand Syrians under temporary protection.Footnote 14

The discourse of ‘cheap labour source’ was made even more prevalent by the members of the ruling party, AKP, during the fieldwork in the summer of 2021. When the Taliban forces started to control larger parts of Afghanistan after the US forces started to withdraw in August 2021, the Turkish mainstream media coverage of irregular Afghan migrants entering the country from the Iranian border alerted the oppositional parties in Turkey to generate a stronger anti-refugee hostility.Footnote 15 Such hostility has been immediately reflected towards the Syrians by a large number of the Turkish population, who were chanting ‘refugees out’, ‘Syrians out’, and ‘Afghans out’.Footnote 16 The members of the ruling government explicitly stated that Turkey would economically suffer even more if the Syrians were deported. It was Yasin Aktay, advisor to the Turkish President, who said Turkish economy would collapse if the Syrians had to leave the country.Footnote 17

Our observations and interviews with the local stakeholders in Bursa and the local region, Karacabey, also confirm the widespread perception of Syrians and other migrants as cheap labour contributing to the local economy. One of our interlocutors involved in the occupational training programs provided by the Bursa Metropolitan Municipality shared with us his thoughts about the employability of Syrians in particular.

Syrians are perceived to be cheap labour. Employers are not willing to go through all that hassle to pay all that money for social security purposes… On the other hand, I also witness that many Syrian entrepreneurs are doing business in Bursa. They have already created a niche economy. Take a look at the Çarşamba district of the city centre. There are many shops owned by the Syrians. They are very organised actually (Interview WP5TRB002).

The interview data demonstrate that Syrians and other migrants are aware of the opportunities existing in the labour market in Karacabey and Bursa. The state of temporariness and the lack of interactions between the locals and migrant communities make it difficult for the migrants to contribute better to the local setting. The state of the temporality of the Syrians is not something that could be changed by the local actors. It could only be changed by the jurisdiction and executive power of the central state actors.

Gender Dimension and Other Challenges in the Labour Market

The situation of Syrian refugees in the Turkish labour market has a strong gender dimension. Syrian women work as flexible labourers at the workplace and at the same time look after their families. They struggle on both ends, i.e. the production and re-production sides of life. At the workplace, they are the most affected and vulnerable agents of the labour market because they are employed with lower wages in comparison with males from other origins. It is very difficult to engage migrant women in having access to the labour market because they are also responsible for domestic household issues. Despite working as a nurse, a female migrant interlocutor in Karacabey puts the challenges into words by stating the following:

There is a disabled person in my family. It is difficult to work and take care of their needs but we try to manage it somehow (…) Life is hard, my husband takes care of the kids until I return, then he leaves to work [collect waste paper] (Interview WP5TRB006).

Addressing the household responsibilities, one of our interlocutors, a female Senior Project Manager from the International Centre for Migration Policy Development (ICMPD) in Ankara, talked about a project that they have currently been working on:

We know that on average migrant-origin individuals are more into entrepreneurial spirit… Turkey has not received a very-well educated group of Syrians, we know that. But they brought different kinds of artisanship, which they learned from their parents and grandparents. They are very good at shoe-making, furniture, other kinds of artisan works. But it is rather difficult to make women involved in employment facilities… We are now working on a Project called ‘Home-based entrepreneurship’. We are trying to find ways to incorporate women into the labour market by engaging them in home-based entrepreneurship on the one hand, and letting them take care of their household responsibilities on the other (Interview WP5TR003).

On the other hand, Syrian males are employed with lower wages in comparison to the Turkish male workers (Tören, 2018). A 50-year-old man from Afrin working in Karacabey as a seasonal worker in the fields said the following to refer to the low salaries that the Syrians earn in the agricultural sector:

We earn 80 TL per day, and 10 percent of this goes to the commissioner who brings us here from Mersin [a coastal city in the eastern Mediterranean region of Turkey]. We are not getting paid the same salary as the Turks. I don’t know how much they earn. We have to meet all the costs resulting from our back and forth travel from Mersin (Interview WP5TRB009).

Both migrant women and men working in Bursa and Karacabey are vulnerable. The vulnerability of seasonal workers employed in the agricultural sector is even more. Gendered assignments made in the vocational training schemes make it harder for migrants to have different options and opportunities existing in the local settings. So far, community sponsorship demonstrated by religious-based local charity institutions was far from equally treating female and male migrants in Karacabey and elsewhere. As UNHCR, (2019, p. 12) notes, community sponsorship should be ‘non-discriminatory and not distinguish on the basis of nationality, race, gender, religious belief, class or political opinion’. The Law on Foreigners and International Protection introduced in 2014 essentially regulates the rules regarding the rights to family union, long-term residence, education, health services, and labour market mobility of regular and irregular migrants. However, it does not specifically regulate the rules regarding political participation, access to nationality, and anti-discrimination.Footnote 18 Discrimination based on gender is also a matter that cannot be left to the discretion of local actors, and it needs to be handled with the introduction of laws and policies formulated at the national level.

Conclusion

This article has revealed the challenges and opportunities in Karacabey, Bursa, by means of a participatory action research conducted in 2020 and 2021. Despite the limitations posed by the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, local participants and migrants were very collaborative in sharing their insight with the research team. Based on the findings of the research, one could conclude that locals are very well aware of the challenges and opportunities in terms of the socio-economic impact of migration on rural development and agricultural production in particular. However, the lack of rural-based approach at the central state level makes it difficult for the local stakeholders in Karacabey to generate stronger models of co-existence between local citizens and migrant-origin individuals engaged in agricultural production processes.

It was also revealed that multilevel governance of mass migration of Syrians and their integration started to have a local turn in the aftermath of the so-called 2015 Refugee crisis since the EU offered financial assistance to Turkey for the incorporation of Syrians under temporary protection to different spheres of life such as having access to education, health services, and labour market. At first glance, the local turn sounds the most appropriate approach in the management of mass migration since its societal, economic, and cultural impacts are mostly local. However, there is a neoliberal logic that lies behind the willingness of the central state actors to delegate responsibilities to local actors (municipalities, NGOs, migrants). Delegation of responsibilities to the local actors has not been in tandem with the allocation of resources by the central state to the local municipalities for instance. Furthermore, the prevalence of the discourse of resilience has been a deliberate attempt of the central state actors to responsibilise refugees in everyday life. Hence, delegation of responsibilities without allocation of resources has not strengthened the local municipalities, NGOs, and refugees.

One of the key challenges of the Turkish ‘local turn’ in migration governance and politics is the fact that local municipalities have a rather minor status in the formation of legal regulations and politics. With reduced delegated power and authority, municipalities lack administrative capacity and adequate resources, which leave them with few legal tools to formulate and implement policies. Many refugees in Turkey have joined racialised and marginalised groups affected by everyday violence of dispossession and neoliberal capitalism and have become the members of the new precariat class in the form of cheap labour. Refugees’ precariousness has been reinforced even more over the last few years since there is a growing popular resentment and hostility against them due to the troubling domestic economic conditions that hit the entire population. Municipal authorities do very little in challenging national immigration regimes that are rendering many people ‘temporary’ and ‘unwanted’. Sanctuary policy of cities and local districts is also limited by jurisdictional mismatch between governments and neoliberal competition for services. The research in Karacabey and Bursa has demonstrated that the local actors are not capable of resolving the socioeconomic challenges and precariousness resulting from the growing numbers of refugees in the rural places without the financial and administrative support of the central state actors. Under current circumstances, neither Karacabey nor any other city can hardly offer migrants and refugees genuine sanctuary conditions.

Change history

17 April 2023

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-023-01037-5

Notes

Since 2017, Turkish Ministry of Health has initiated a project funded by the European Union to offer health services to the migrants: SIHHAT Project (Health Project). During the research, there were 177 Migrant Health Centres in 29 provinces in Turkey. For more details on SIHHAT Project, see https://eng.sihhatproject.org/. Accessed 21 December 2022.

For the EU-Turkey Refugee Statement see https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2016/03/18/eu-turkey-statement/. Accessed 09 December 2022.

For the full text of the July 3, 2005, dated Municipal Law No. 5393, see https://www.mevzuat.gov.tr/mevzuat?MevzuatNo=5393&MevzuatTur=1&MevzuatTertip=5. Accessed 03 December 2022.

For the Law No. 6360 see https://www.resmigazete.gov.tr/eskiler/2012/12/20121206-1.htm. Accessed 10 December 10, 2022.

For the distribution of Syrians under temporary protection by province, see the website of DGMM, https://www.goc.gov.tr/gecici-koruma5638. Accessed 09 August 2022.

See https://www.goc.gov.tr/gecici-koruma5638. Accessed 09 August 2022.

For the Regulation of Work Permits of Foreigners under Temporary Protection, see https://www.mevzuat.gov.tr/mevzuatmetin/3.5.20168375.pdf. Accessed 03 December 2022.

For the Law 8375 see https://turkishlaborlaw.com/news/legal-news/362-turkey-grants-work-permit-for-syrian-refugees. Accessed 03 December 2022.

Source: Bursa Provincial Directorate Social Security Institution, 10 August 2021.

For detailed information about the Emergency Social Safety Net (ESSN), see http://www.essncard.com/tr/. Accessed 28 July 2022.

See https://www.ailevecalisma.gov.tr/uigm/duyurular/04042019-nolu-duyuru/. Accessed 12 August 2022.

See https://www.legislationline.org/download/id/6585/file/Turkey_citizenship_law_2009_en.pdf. Accessed 12 August 2022.

See https://multeciler.org.tr/turkiyedeki-suriyeli-sayisi/. Accessed 12 August 2022.

For a review of the anti-refugee hostility raised by the oppositional parties such as the Republican People’s Party (CHP), see https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2021/aug/05/fleeing-the-taliban-afghans-met-with-rising-anti-refugee-hostility-in-turkey/. Accessed 14 August 2022.

For more debate on this, see https://bianet.org/english/world/248842-the-west-will-pray-for-erdogan-s-reelection-as-new-refugee-crisis-looms-says-chp-leader. Accessed 19 August 2022.

See https://newsbeezer.com/turkeyeng/erdogans-advisor-yasin-aktay-turkey-has-to-live-with-syrian-refugees/. Accessed 15 August 2022.

For a detailed analysis of the state of integration policies of the Turkish Republic, see the website of the Migration Integration Policy Index (http://www.mipex.eu) based in Brussels. For further information on MIPEX see http://www.mipex.eu, accessed 10 December 2022.

References

Adger, W. N. (2000). Social and ecological resilience: Are they related? Progress in Human Geography, 24(3), 347–364.

Ak, I. (Ed.) (2017). Karacabey Sempozyumu Bildiriler Kitabı. Bursa: Dora Basın Yayın Dağıtım.

Akay, K., & Doğan Yenisey, K., (2021). Report Turkey. In M. L. Caputo, M. Bianchi, M. Lo Cascio, & S. Baglioni (Eds.), 10 Country reports economic impact 278–303. Deliverable 4.3 MATILDE Horizon 2020 project.

Arıcı, I., & Kirmikil, M. (2017). Büyükşehir Belediyesi Kanunundan Sonra Kırsal Alandaki Olası Gelişmeler, In I. Ak (ed.), Karacabey Sempozyumu Bildiriler Kitabı. Bursa: Dora Basın Yayın Dağıtım 39–46.

Aydemir, N. (2022). Framing Syrian refugees in Turkish politics: A qualitative analysis on party group speeches. Territory, Politics, Governance. https://doi.org/10.1080/21622671.2021.2012247

Barber, B. R. (2013). If mayors ruled the world: Dysfunctional nations, rising cities. Yale University Press.

Baumgärtel, M., & Miellet, S. (Eds.). (2022). Theorizing local migration law and governance. Cambridge University Press.

Bendel, P., Schammann H., Heimann C., & Sturner, J. (2019). A local turn for European refugee politics recommendations for strengthening municipalities and local communities in refugee and asylum policy of the EU (March). Heinrich Böll Foundation.

Betts, A., Memisoglu, F., & Ali, A. (2021). What difference do mayors make? The role of municipal authorities in Turkey and Lebanon’s response to Syrian Refugees. Journal of Refugee Studies, 34(1), 491–519.

Bourbeau, P. (2015). Migration, resilience and security: Responses to new inflows of asylum seekers and migrants. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 41(12), 1958–1977.

Caponio, T., & Borkert, M. (2010). The local dimension of migration policymaking. Amsterdam University Press.

Caponio, T., Scholten, P., & Zapata-Barrero, R. (Eds.). (2019). The Routledge handbook of the governance of migration and diversity in cities. Routledge.

Caro, L. P. (2020). Syrian refugees in the Turkish labour market. International Labour Organisation.

Chandler, D. (2014). Beyond neoliberalism: Resilience, the new art of governing complexity. Resilience, 2(1), 47–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/21693293.2013.878544

Chatty, D. (2013). Guests and hosts: Arab hospitality underpins a humane approach to asylum policy. The Cairo Review of Global Affairs, 19 (22 April). http://www.aucegypt.edu/GAPP/CairoReview/Pages/articleDetails.aspx?aid=335. Accessed 22 October 2022.

Chemin, E. J., & Nagel, A. K. (2020). Germany: reception policies, practices and responses. WP4 Germany Country Report, RESPOND Project. https://www.respondmigration.com/wp-blog/refugee-reception-policies-practices-responses-germany-country-report.

Coşkun, G. B., & Uçar, A. Y. (2018). Local responses to the Syrian refugee movement. Movements, 4(2), 103–246.

Cretney, R. (2014). Resilience for whom? Emerging Critical Geographies of Socio-Ecological Resilience. Geography Compass, 8(9), 627–640.

Dean, M. (2014). Rethinking neoliberalism. Journal of Sociology, 50(2), 150–163.

Dobrowolsky, A. (2013). Nuancing neoliberalism: Lessons learned from a failed immigration experiment. Journal of International Migration and Integration, 14, 197–218.

Durmuş, E. (2022). Breaking free: local governments’ boundary-defying engagement with human rights and migration. Unpublished PhD Dissertation, University of Utrecht.

Erdoğan, M., Kirişçi, K., & Uysal, G. (2021). Multi-country project on covid-19 impacts on refugees in Jordan, Lebanon and Turkey: Turkey report. Report, World Refugee and Migration Council and IGAM Academy.

Filomeno, F. A. (2016). Global cities and local immigration policy in Latin America. Proceedings of the XXXIV International Congress of the Latin American Studies Association, New York City, May, 27–30.

Hooghe, L. & Marks, G. (2001). Types of multi-level governance. European Integration Online Papers.

Inda, J. X. (2006). Targetting immigrants: Government, technology and ethics. Blackwell Publishing.

Joseph, J. (2013). Resilience as embedded neoliberalism: A governmentality approach. Resilience, 1(1), 38–52.

Kale, B., & Erdoğan, M. (2019). The impact of GCR on local governments and Syrian refugees in Turkey. International Migration, 57(6), 224–242.

Kaya, A., & Nagel, A. K. (2021). Politics of subsidiarity in refugee reception: Comparative perspectives. Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies, Special Issue, 19(3), 235–244.

Kaya, A. (ed.) (2020). Syrian migration to Turkey and municipal experiences: mass migrations and local responses, RESLOG, Ankara, http://www.reslogproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/reslog_KIT_birlikte_yasam_ENG_ONLINE.pdf

Lewin, K. (1946). Action research and minority problems. Journal of Social Issues, 2, 34–46.

Lewis, D. (2020). The concept of resilience: emergence, evolution and operationality. Ankara: Reslog Project, http://www.reslogproject.org/en/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/reslog_KIT_goc_ve_yonetisim_ENG_ONLINE-2-1.pdf

Mackreath, H. & Sağnıç, Ş. G. (2017). Civil society and Syrian refugees in Turkey, İstanbul: Citizens' Assembly

Mavelli, L. (2017). Governing the resilience of neoliberalism through biopolitics. European Journal of International Relations, 23(3), 489–512.

Mayntz, R. (2003). New challenges to governance theory. In H. Bang (Ed.), Governance as social and political communication (pp. 27–40). Manchester University Press.

McTaggart, R. (2010). Participatory action research: international contexts and consequences. SUNY Series, teacher preparation and development. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Memisoglu, F., & Yavcan, B. (2022). Beyond ideology—a comparative analysis of how local governance can expand national integration policy: The case of Syrian refugees in Istanbul. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 48(3), 503–523.

Mencütek, Z. Ş, Aras, E., Kaya, A., & Rottmann, S. (2023). Syrian refugees in Turkey: Between reception and integration. Imiscoe.