Abstract

Economic and social conditions have deteriorated worldwide during the COVID-19 pandemic. Migration theory and international organizations indicate that these increasingly fragile social conditions represent powerful incentives to migrate. Normally, studies addressing international migration and COVID-19 focus on transit and destination countries, with substantially less literature centered on origin nations. Trying to close that gap, the present article aims to identify and quantify economic determinants that explain the intention of Salvadorians to migrate abroad. Using a probabilistic sample and a logistic model, a number of renowned economic variables for migration studies were used to investigate Salvadorian’s intention to emigrate. Results demonstrated a stark reduction in migration intentions in 2020. Moreover, the risk of losing one’s job is by far the most prominent factor explaining the intention to migrate. Other aspects, such as employment and salaries, also showed statistically significant values. Additionally, results report women being less likely to migrate and age to have a negligible effect. The text concludes by indicating some public initiatives that could be implemented to support people who choose to act upon their intentions and embark on emigration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Salvadorians have been closely linked to international migration throughout the twenty-first century. In 1974, the laureate and assassinated poet, Roque Dalton, referred to his fellow Salvadorians in his Love Poem as: “the planters of corn deep down foreign jungles, they who were cooked by bullets when crossing the border… the ones who hardly made it back… the eternally undocumented (illegal).” This historical link to international migration has led to large numbers of Salvadorians living abroad. While El Salvador has an estimated population of six million inhabitants living within the country, three more million live abroad (Consejo Nacional para la Protección y Desarrollo de la Persona Migrante y su Familia — CONMIGRANTES, 2017).

In light of the importance of migration, several actors, including governments, academia, and civil society, have devoted to analyzing and understanding this phenomenon. Hence, official information depicts international emigration flows to settle in countries within the American Hemisphere, particularly the USA (CONMIGRANTES, 2017). While residing within this country, Salvadorian diaspora tends to settle in southern border states, such as California and Texas (CONMIGRANTES, 2017; Obinna, 2019). The former east coast state is home to the largest Salvadorian community abroad (CONMIGRANTES, 2017; Obinna, 2019). Other west coast states, such as New York, Maryland, New Jersey, and Virginia, are also common destinations within US territory (CONMIGRANTES, 2017; Obinna, 2019). Salvadorians usually find jobs in low-skilled sectors such as commerce, construction industries, and hospitality (CONMIGRANTES, 2017; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development-OECD, 2021). According to the International Organization for Migration (2017), 48.8% of Salvadorians living abroad possess an irregular statusFootnote 1. Likewise, emigration of Salvadorians is mainly driven by economic factors followed by civil violence and family reunification (CONMIGRANTES, 2017; International Organization for Migrations (IOM), 2017).

The relevance of Salvadorian diaspora is also present in the USA. As of 2018, Salvadorians ranked as the fifth foreign-born population living in the USA (Pew Research Center, 2020). In addition, the Salvadorian diaspora gained two additional spotlights in mainstream US media in 2019–2020 thanks to migrant caravans and the unaccompanied migrant crisis. Numerous people traveling in caravans to the USA came from El Salvador. Along with Guatemalan and Honduran children, El Salvador was the birthplace of many unaccompanied migrant minors traveling to the USA in fiscal year 2020 (Congressional Research Service, 2020). Northern Central American countries together accounted for 77% of all unaccompanied minors registered by the US border service in the same period (Congressional Research Service, 2020).

Despite civil violence being particularly cruel in El Salvador (Martínez, 2014; Valencia, 2011), and in spite of recent attention brought to the topic by international media and renamed politicians (Davis & Chokshi, 2018; Finley & Esposito, 2020), economic drivers seem to be by far the main reasons for emigration. Unemployment, underemployment, or income gaps have been historical incentives for Salvadorians to migrate abroad. Specifically, these economic indicators registered an evident worsening throughout 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. As a result, negative trends were reported for El Salvador in key economic indicators including household income, job destruction, and the number of workers contributing to social security (Fundación Salvadoreña para el Desarrollo Económico y Social-FUSADES, 2020b). Similarly, numerous workers had their contracts suspended in light of the quarantine law and the lockdown order mandated in April 2020. All these indicators were only symptoms of an economic recession for El Salvador, as the International Monetary Fund, IMF (2020) forecasts a 9% real gross domestic product shrinkage, which represents the worst result in the entire Central American region.

This poor economic performance is excepted to have a direct impact on Salvadorian households. Thus, Fundación Salvadoreña para el Desarrollo Económico y Social (FUSADES, 2020a) estimates that multidimensional poverty could increase from 33.7% in 2019 to 51.4% in 2020. Similarly, other well-being indicators are likely to be affected. To this regard, Ayala (2020) highlighted discouraging perspectives on food security for the country through 2020. This concern was already shared by FAO and UNDP in 2016, as they reported that up to 49.4% of Salvadorian households faced some type of food insecurity (Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Alimentación y Agricultura (FAO); Programa de las Naciones Unidas para el Desarrollo (PNUD), 2016). These fragile conditions are coupled with inefficient emergency government policies during the pandemic (Ayala Durán, 2021), exacerbating social indicators in vulnerable populations such as the elderly, the disabled, or those in informal employment.

Given the history of emigrating mainly due to economic reasons and in light of deteriorating social conditions within the country, there is a latent possibility that large numbers of people decide to emigrate to traditional destinations. Regarding this possibility, the International Organization for Migration and World Food Program (2020) warned that food insecurity becomes an important driver for emigration. Despite the social fragility observed worldwide during this pandemic, Herm and Poulain (2012, p.148) underline that, when economic conditions deteriorate in rich countries, they may worsen even more in poorer countries of origin, further motivating migration. Similarly, King (2012) states that, following the 2008 economic crisis, migration is likely to continue being important in the future due to continuing strong pressures for global integration and people’s desire to improve their life opportunities. If migration materializes and large numbers of Salvadorians decide to migrate, this could have important social and public health implications.

Assuming people choose the USA as their main destination country, social challenges include increased travel restrictions throughout 2020. It is well established that migration policy under the Trump administration was unwilling to receive migrants from Latin American countries and to process their asylum applications rapidly (Fullerton, 2017; Scribner, 2017). Media reports and academic studies showing underage migrants and infant children being separated from their parents were examples of the difficulty in migrating to the USA during the 2017–2021 period (Garrett, 2020; Mendoza, 2018; Monico et al., 2019). On the other hand, focusing on public health challenges, Guadagno (2020) points out the precarious and unsanitary conditions under which many people migrate. In addition, people attempting to migrate irregularly to the USA may find themselves relying upon overcrowded shelters and mass caravans, thus increasing the risk of COVID-19 infections and transmission. Likewise, once in the USA (as well as in other transit countries), migrants often rely on unstable, informal, and temporal jobs (International Organisation for Migrations (IOM) & World Food Program (WFP), 2020). Moreover, access to health services is not always guaranteed in both transit and destination countries (INTERNATIONAL ORGANISATION FOR MIGRATIONS, IOM, 2019; IOM; WORLD FOOD PROGRAM, WFP, 2020).

Despite the importance of foreseeing migration flows in countries of origin, transit, and destination, studies addressing international migration and the pandemic tend to focus on transit and final destinations (Guadagno, 2020; International Organisation for Migrations, IOM, 2020). Therefore, only a limited number of studies (Bah et al., 2021; Catholic Relief Services, 2020; Programa de las Naciones Unidas para el Desarrollo & Organización Internacional para las Migraciones, 2021) focus on origin countries.

In light of the changing scenario brought about by COVID-19, and given the worsening of social conditions in El Salvador, this research aims to identify and quantify economic determinants explaining the intention of Salvadorians to migrate. Hence, this article arises as an exploratory work to begin understanding possible migration flows linked to COVID-19 in El Salvador. Such a study proves to be increasingly crucial, given that migration can become a strategy for improving household income and food security (IOM & WFP, 2020).

To implement this research, a database composed of a nation-wide probabilistic sample (n = 1222) was employed. This database inquired, among others, people’s strategies for co** with the pandemic. Specifically, some respondents expressed their intention to migrate as a means to counteract increasingly challenging social conditions. For the statistical analysis, a logistic regression was used to model Salvadorians’ intention to emigrate. The rest of this study is structured as follows: A brief review of the literature on migration and economic crisis is presented, providing theoretical grounds to address the Salvadorian case. Subsequently, the materials and methods are described, which paves the way to present the results. After, a discussion section is elaborated. The text closes with concluding remarks.

Materials and Methods

This section is divided into two subparts. First, a brief discussion of migration theory is presented, which justifies the selection of variables and provides an overview of relevant previous studies. After, the model specification is explained.

Literature Review

Focusing on migration theories, relevant literature explores the link between migration and health. Approaches include social determinants of health, transnationalism, and structural vulnerability (Castañeda et al., 2015; Villa-Torres et al., 2011; Rubin & Wagner, 2015), and at a country level (Blomberg & Mody, 2005; Loureiro & Silva, 2010). Negative effects include reduced productivity, poor access to credit, low investment, and slow economic growth. Moreover, climate change and weather abnormalities can also affect migration (Halliday, 2006; Marchiori et al., 2012; Nawrotzki et al., 2013). For instance, Nawrotzki et al. (2013) showed the relevance of disturbed rainfall patterns in explaining rural Mexican migration to the USA. In the case of El Salvador, Halliday (2006) found that adverse agricultural conditions pushed household members to migrate to the USA, while earthquake-affected households showed an opposite tendency.

Despite having a growing body of theory pointing to political, environmental, human rights, and psychological factors influencing international migration (Etling et al., 2020; Halliday, 2006; Hiskey et al., 2014; Lundquist & Massey, 2005; Nawrotzki et al., 2013; Schon, 2019) and a pressing need for interdisciplinary research to better understand human migration (Brettell & Hollifield, 2015); economic factors maintain their prominence as the main drivers in international migration studies. Remarkably, Salvadorians migrate primarly for economic reasons (CONMIGRANTES, 2017; IOM, 2020). Therefore, whether from a theoretical (King, 2012; Lafleur & Stanek, 2017) or empirical perspective (Clark et al., 2007; Herm & Poulain, 2012; Mayda, 2010; Romero-Valiente, 2018), economic performance is critical to understand international migration flows.

The relevance of economic factors as migration drivers in addition to worsening social conditions brought on by the 2020 pandemic add powerful stimuli for Salvadorians to consider migration as a viable option. Drawing upon relevant studies (Brettell & Hollifield, 2015; Herm & Poulain, 2012), this research takes into account key economic aspects such as employment, risk of employment loss, and wages as explanatory factors for the intention to migrate. Other demographic characteristics are included in the analysis, as detailed in the following methodological section.

Data and Methods

Obtaining reliable and up-to-date information on migrants is always a major challenge for any country in the world and, as the pandemic drags on, the task becomes even more arduous. Moreover, there is no public database collecting migration information for Salvadorians to the knowledge of this author, adding yet another layer of difficulty. As such, information collected by Centro de Estudios Ciudadanos (2020) was used. This organization, which is part of Francisco Gavidia University, conducted a much larger study and surveyed people via phone call in 2020. Their study focused on the Salvadorian State’s handling of the COVID-19 pandemic (three branches). This was one of the earliest studies carried out in the country, collecting information only a month after the beginning of the pandemic in 2020. Using a probabilistic sample of adults (18 years or older) and gathering information at the national level, a total of 1222 respondents were surveyed, relying on a 95% confidence interval with an estimated error of 2.5%. Those parameters allow for this to be a representative sample of the Salvadorian population. People were surveyed between the 23rd and 27th of April 2020, at the beginning of the quarantine and lockdown mandate. By the time people were surveyed, internal movement within the country was prohibited. Similarly, international travel was banned, including Salvadorian nationals trying to return to the country. The few exceptions to this strict quarantine were essential workers and humanitarian travel.

Among questions included in the Centro de Estudios Ciudadanos (2020) survey, one pertained to the strategies people used to cope with the COVID-19 pandemic in El Salvador. Some responses reflected an intention to migrate, an action that was materially impossible at the time of data collection. However, these questions serve to question people’s intention to migrate as a survival strategy. For the implementation of the model, the intention to migrate was coded into a binary variable assigning the value 1 when people expressed the intention to migrate and 0 otherwise. Subsequently, logistic regression was used to predict the associated characteristics using economic performance indicators widely employed in migration studies as independent variables, according to Table 2. These economic variables have been widely assessed as determinants of migrations, both from a theoretical perspective (Castles, 2009; King, 2012); and an empirical one (Etling et al., 2020; Hiskey et al., 2014; Romero-Valiente, 2018). Similarly, demographic variables such as age, gender, or residence in rural areas were included as control variables, in line with other relevant studies (Etling et al., 2020; Fundación para la Educación Superior, 2019; Hiskey et al., 2014; Schon, 2019). The database and this paper were not of longitudinal nature and could not attest to whether or not respondents actually migrated. However, the literature indicates that migration intention serves as an appropriate proxy of actual migration behavior (Tjaden et al., 2019; van Dalen & Henkens, 2008; Wanner, 2021). Remittances can also serve as an approximation of household members who have already migrated, namely a migrant network (Chinchilla & Hamilton, 1999).

Hosmer & Lemeshow test and the area under the curve were used to evaluate the model fit. The first test reported a statistical significance of 0.422. The area under the curve reported 0.710, and its statistical significance was 0.00, all indicating a good model fit. All variables and analysis were performed with SPSS 26.

Results

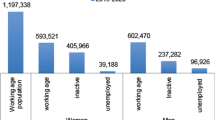

Descriptive statistics are summarized in Table 3. Information presented depicts that the majority of people intending to migrate are men. Likewise, a notable proportion of people express receiving international remittances. The average age difference between people who report having an intention to migrate and those who do not accounts to 5 years. The total number of people expressing an intention to migrate is low, representing only 6.38% of the total sampleFootnote 2. This represents an evident decrease from other surveys inquiring Salvadorians’ intention to migrate. For example, America’s Barometer by Vanderbilt University shows a historical trend of 23.5–36.3% of Salvadorians expressing their intention to migrate (Vanderbilt University, 2021). Other recent studies (Instituto Universitario de Opinión Pública, 2021; Organización Internacional para las Migraciones, 2020) report figures similar to Venderbilt University (2021). This sharp decline appears to be explained by the conditions imposed by the pandemic in El Salvador and around the world.

According to Programa de las Naciones Unidas para el Desarrollo & Organización Internacional para las Migraciones (2021), deterrents for Salvadorian emigration during the pandemic include fear of COVID-19 infection, reduced work opportunities abroad, enhanced migration restrictions, and decreased personal and family income. Other studies in the Gambia (Bah et al., 2021) and neighboring Guatemala (Catholic Relief Services, 2020) have indicated similar reasons discouraging emigration, particularly those related to lower perceived job opportunities abroad and household financial liquidity.

Despite these added complications, and as noted by Herm and Poulain (2012), challenging economic conditions in rich countries may be even more dramatic in develo** nations, further stimulating migration. In light of publicly available information, this appears to be the case: initially, an original reduction emigration was observed, followed by a rapid increase in US inflows (US Custom and Border Patrol, 2021; Voice of America, 2021). In particular, at the end of fiscal year 2021, US authorities registered a record high of Salvadorians apprehended at the southern border (Voice of America, 2021). This would indicate the existence of an initial and temporary deceleration of Salvadorian emigration. However, official data suggests the temporary trend has ended, as high numbers of apprehensions are now being recorded (US Custom and Border Patrol, 2021) and newer surveys reflect increased migration intentions (Instituto Universitario de Opinión Pública, 2021).

Additionally, results from the logistic regression are presented in Table 4. Overall, employment-related variables do influence the intention to migrate. Thus, being employed (p value ≤ 0.028) and the risk of losing one’s employment (p value ≤ 0.006) present a negative relationship with the decision to migrate. Likewise, age and squared age also present significant values, although their influence seems to be almost imperceptible. In addition, certain monthly income substrata seem to be associated with the intention to migrate, particularly those with average income of 211–$350 (p value ≤ 0.033), 350.01–$500 (p value ≤ 0.055), and 700.01–$1000 (p value ≤ 0.088). Finally, women are less prone to migrate than men.

Discussion

Among demographic features associated with the intention to migrate, gender and squared age reported statistically significant values. Results showed that women were less likely to migrate than men (p value ≤ 0.017, OR = 0.532). A similar trend was identified by official reports (Consejo Nacional para la Protección y Desarrollo de la Persona Migrante y su Familia-CONMIGRANTES, 2017). Additionally, squared age seems to only have minor effects on the intention to migrate, being near imperceptible. This trend contradicts Sandoval’s (2020) findings, as he portrays young people participating more actively in emigration even under adverse circumstances. Sandoval (2020, 97) summarizes these comments by stating,

The question then arises, why do people continue to cross all of Mexico and arrive at the US border to try to enter [the US] illegally if it is increasingly difficult? One possible answer is structural, criminal and gender-based violence. This materializes as mentioned above in unemployment, lack of educational opportunities, extortion and death, as well as many other life-threatening situations (Author’s translation).

Other studies have also identified a large proportion of Salvadorian men migrating before 20 years of age (Fundación para la Educación Superior- FES, 2019). Similarly, Tintori and Romei (2017) state that after the 2008 economic crisis, Italian youth were much more likely to emigrate driven by economic and labor reasons.

Focusing on the economic characteristics regarding the decision to migrate, results show that employment, risk of employment loss, and some substrata of income are significant. Therefore, an employed person is less prone to migrate (p value ≤ 0.028, OR = 0.544). Similar results have been found by Simon et al. (2022) during the COVID pandemic, as they highlight the prominence of employment in migration intentions. Some pre-pandemic studies also highlight that employment and employment quality are key in emigration behavior from southern European countries (Lafleur & Stanek, 2017; Marques & Góis, 2017; Tintori & Romei, 2017). To that extent, Tintori and Romei (2017) highlight how Italians with a stable employment (positions not regulated by the 2003 and 2012 labor reform) are less likely to emigrate. Therefore, job stability and working conditions seem to be important in the decision to migrate, both in Italy and in El Salvador.

Closely related to employment, people who face the risk of losing their job consider migration to be a valid option for co** with the economic crisis. This variable was by far the most influential in explaining the intention to migrate (p value ≤ 0.006, OR = 2.018). In addition, El Salvador reported a marked decrease in the number of jobs, suspension of contracts, and a decrease in the number of people contributing to social security during 2020 (FUSADES, 2020b). The intention to emigrate from the origin country when facing the risk of losing one’s job can be explained, from a theoretical point of view, as a perception of the labor demand in other nations (push-pull) or as a way for families to reduce the risk of losing income (NELM) (King, 2012). In addition, Simon et al. (2022) reported that employment served during the current pandemic as a social anchor for staying in origin countries. As reported by CONMIGRANTES (2017) and given the vast majority of Salvadorians abroad live in the US (2.89 million, 93% of the total), it is likely that people will consider migrating to this North American nation. Should such a scenario materialize, transit and destination countries (Guatemala, Mexico, and the United States) would also face health challenges associated with increased migration flows, as people normally travel in groups (Marchand, 2021; Martínez, 2021). Even when faced with extreme mobility restrictions in Central and North America, migrant caravans were increasingly used as a method for traveling to the US since 2011 (Marchand, 2021). After a pause caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, migrant caravans re-emerged in late 2020 and early 2021 (Martínez, 2021; Semple & Wirtz, 2021).

In addition, some income levels also showed statistically significant values. Therefore, people reporting a monthly household income of 211–$350 (p value ≤ 0.033, OR = 0.448), 350.01–$500 (p value ≤ 0.055, OR = 0.449), and 700.01–$1000 (p value ≤ 0.088, OR = 0.416) were less prone to migrate when compared to people having a monthly family income of less than $211 (base category). These account for mixed results, with the top and bottom strata showing a lower propensity to migrate compared to the base category. Focusing on the 211–$350 strata, the aversion to migrate can be explained by the monetary constraints and resources needed to undertake the migratory journey. For example, IOM (2017) estimates that attempts to enter the USA by Salvadorians can cost between 3090 and $6384. This difference depends on the method chosen to migrate: individually for the lower amount and accompanied/supported by smugglers (pollero, collote) for the upper limit. Additionally, at the time of data collection, a reduction in family income was expected due to a lockdown order in El Salvador. This expectation could represent an important deterrent to engage in migration, even when it is only referring to intentions to migrate.

While the former explanation is possible, the 350.01–$500 and 700.01–$1000 strata also implied a less favorable tendency to migrate than those in the base category. This could be explained by two reasons: economic needs already covered and lower expected returns abroad. Theoretical approaches emphasize the importance of economic performance as a key pushing factor in international migration (de Haas, 2010; King, 2012; Tilly, 2011). Salvadorian emigration, although multi-caused, is fueled by poor economic indicators, particularly work opportunities and income differentials (Organización Internacional para las Migraciones, 2020). People with higher income and who have their basic needs met may be unwilling to emigrate. To this regard, Simon et al. (2022) refer to employment as a social anchor in countries of origin. Additionally, in the face of the foreseeable global economic recession, migration could represent a less attractive option for Salvadorians with these income substrata. In neighboring Guatemala, for example, the reduction of expected employment opportunities abroad emerged as a deterrent in the decision to migrate (Catholic Relief Services, 2020). Similarly, Bah et al. (2021) point in the same direction by emphasizing the reduction of pulling factors for Gambian immigration to Europe, as unemployment rises, COVID-19 infections increase, and expected income declines in destination countries.

Thus, for opposite reasons, the upper and lower-income strata appear to have fewer incentives (or less capacity) to migrate. Considering this mixed evidence in El Salvador, it becomes increasingly important to further study income levels and intention to migrate in more depth, particularly since much of migration theory relies on wage and labor differences between origin and destination countries. Similarly, the number of people showing an intention to migrate is relatively low in this study, making it necessary to study migration intentions with larger samples in the post-COVID-19 era.

A variable that is commonly associated with migrant networks and even to family members living abroad is the reception of remittances. Surprisingly, remittances did not report any significant relationship with the intention to migrate. According to IOM (2017) estimates, 20% of Salvadorian households receive remittances. Under the new economics of labor migration (King, 2012), this could indicate that, if a household already has a family member working abroad and sending remittances to the home country, it would then be unnecessary for an additional member to embark on emigration. However, it is also possible that more than one household member has emigrated abroad, which in turn would allow for more than one person to contribute with remittances.

Focusing on remittances and development, Fernandez (2010) pointed out that these international cash flows can represent a valid strategy for co** with economic crises in develo** countries. In the case of El Salvador, Acevedo and Cabrera (2014) highlight how remittances have helped to reduce income inequality in the country. According to these authors, remittances contributed for households to cope with ineffective public policies, thus generating an equalizing effect (Acevedo & Cabrera, 2014). Similarly, the International Organisation for Migration- IOM and World Food Program, WFP (2020) stress the importance of remittances to reduce household uncertainty and to satisfy basic needs within origin countries. In addition, these social and family networks have proven to be fundamental when migrating to the USA, especially when traveling irregularly. To this regard, IOM (2017) reports that in 41.2% of cases, family members support and finance the migratory journey, thus reinforcing the link between family, migration, and remittances. This can represent a migrant network (Chinchilla & Hamilton, 1999).

On the other hand, people from rural areas are not more likely to migrate, despite having more fragile economic indicators. According to Fundación para la Educación Superior, FES (2019), people living in rural settlements more intensively report economic grounds as main reasons for emigrating. Similarly, rural areas and farmers in Central America (especially the dry corridor) face additional climate challenges that threaten their livelihoods (IOM & WFP, 2020). Under this circumstances, it would have been expected that people living in rural areas would be more willing to migrate. However, migratory journeys are costly, which could imply that people from rural areas would face greater difficulties to cover those expenses. To that extent, the cost of migrating to the USA (solo travel) is much higher than the annual minimum wage of rural workers in El Salvador (IOM, 2017).

With all of the above findings, it is critical to provide adequate assistance to Salvadorian migrants who effectively materialize their intention to emigrate in the midst of this ongoing pandemic, particularly for those engaging in irregular migration. Therefore, IOM and WFP (2020) already provide several valuable recommendations to address this vulnerable group: securing access to critical services and inclusive information, as well as ensuring that migrants facing acute hardship can access humanitarian assistance. Similarly, the Salvadorian State holds a key role in providing appropriate aid through its consular and diplomatic network, which could deliver vital assistance during the current public health emergency. Additionally, working with transit and destination countries becomes increasingly crucial, as shelters and detention centers for asylum seekers can become COVID-19 hotspots (Keller & Wagner, 2020).

Final Remarks

Understanding potential international migration flows during the COVID-19 pandemic has become a pressing need for countries of origin, transit, and destination. For a society such as El Salvador’s, with a longstanding tradition of emigration and with almost half of its inland population living abroad, the need becomes even more vital. This public health emergency may generate additional social and health risks for an already fragile population of irregular Salvadorian migrants. According to the results presented, only a small proportion of people intend to emigrate to counteract the effect of the pandemic. However, this tendency appears to be a momentary lapse explained by the health and mobility restrictions brought by the pandemic, with a bounce-back tendency and a record high in migration flows.

Based on migration theory, this research has identified some economic determinants crucial for understanding the decision to leave. Among these factors, the risk of losing employment arises as the most prominent variable explaining the intention to migrate. In light of this and regardless of income level, people are more likely to emigrate when faced with the possibility of losing their work. Surprisingly, receiving international remittances, which could represent a proxy for the existence of migrant networks, does not significantly affect the intention to migrate. However, and as previously noted, this could be partially explained by migration theory, particularly by the new economics of labor migration.

Moreover, it is important to highlight that a share of people considering migration as a valid option might not properly consider the related social, economic, or health risks. However, following Herm and Poulain (2012), when economic conditions deteriorate in rich countries, they may worsen even further in poorer countries of origin, thus adding an additional motivation to engage in migration. It becomes then an increasing need to provide valid information and relevant assistance to those who do migrate. Likewise, providing assistance to irregular migrants, especially those who participate in migration caravans, may be a priority for public and international institutions. To that effect, the Salvadorian government and the international community should consider these economic determinants when formulating public policies and cooperation schemes for the country, since focusing on these determinants could have a direct impact on Salvadorian migration flows. Lastly, public action and resources to understand migration flows during the COVID-19 pandemic should remain a high priority.

Notes

According to IOM, irregular migration is the movement of persons that takes place outside the laws, regulations, or international agreements governing the entry into or exit from the state of origin, transit, or destination. Further information can be found at the International Organization for Migration, 2019

In light of the low number of people expressing their intention to migrate, results hereinafter should be read with caution, as this may have an effect on statistical inference

References

Acevedo, C., & Cabrera, M. (2014). Social policies or private solidarity? The equalizing role of migration and remittances in El Salvador. In Falling Inequality in Latin America (pp. 164–187). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198701804.003.0008

Ayala, C. (2020). Seguridad alimentaria y nutricional en tiempos de COVID-19: perspectivas para el Salvador. Revista Latinoamericana de Investigación Social, 3(1), 42–46.

Ayala Durán, C. (2021). COVID-19 monetary transfer in El Salvador: Determining factors. Revista de Administração Pública, 55(1), 140–150. https://doi.org/10.1590/0034-761220200421

Bah, T., Batista, C., Gubert, F., & Mckenzie, D. J. (2021). How has COVID-19 affected the intention to migrate via the backway to Europe and to a neighboring African country? Survey evidence and a salience experiment in The Gambia (No. 9658; Policy Researcg Working Papers). World Bank Group.

Blomberg, S. B., & Mody, A. (2005). How severely does violence deter international investment? SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.722812

Bogoch, I. I., Creatore, M. I., Cetron, M. S., Brownstein, J. S., Pesik, N., Miniota, J., Tam, T., Hu, W., Nicolucci, A., Ahmed, S., Yoon, J. W., Berry, I., Hay, S. I., Anema, A., Tatem, A. J., MacFadden, D., German, M., & Khan, K. (2015). Assessment of the potential for international dissemination of Ebola virus via commercial air travel during the 2014 west African outbreak. The Lancet, 385(9962), 29–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61828-6

Brettell, C. B., & Hollifield, J. F. (2015). Migration theory: Talking across disciplines (3rd ed.). Routledge.

Brück, T., Naudé, W., & Verwimp, P. (2011). Small business, entrepreneurship and violent conflict in develo** countries. Journal of Small Business and Entrepreneurship, 24(2), 161–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/08276331.2011.10593532

Brück, T., D’Errico, M., & Pietrelli, R. (2019). The effects of violent conflict on household resilience and food security: Evidence from the 2014 Gaza conflict. World Development, 119, 203–223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.05.008

Castañeda, H., Holmes, S. M., Madrigal, D. S., Young, M.-E. D., Beyeler, N., & Quesada, J. (2015). Immigration as a social determinant of health. Annual Review of Public Health, 36(1), 375–392. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182419

Castles, S. (2009). Migration and the global financial crisis: A virtual symposium. Update 1.A: an overview.

Catholic Relief Services. (2020). Entre el arraigo y la decisión de migrar. Un estudio sobre los principales factores que influyen en la intención de permanecer en el país de origen o migrar. CRS.

Centro de Estudios Ciudadanos. (2020). Bukele: Inmune a la pandemia del COVID19. Revista Disruptiva. https://www.disruptiva.media/bukele-inmune-a-la-pandemia-del-covid19/. Accessed 2 June 2020.

Chinchilla, N., & Hamilton, N. (1999). Changing networks and alliances in a transnational context: Salvadoran and Guatemalan immigrants in Southern California. Social Justice, 26(3 (77), 4–26.

Clark, X., Hatton, T. J., & Williamson, J. G. (2007). Explaining US immigration, 1971–1998. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 89(2), 359–373.

Congressional Research Service. (2020). Unaccompained alien children: An overview. CRS.

CONMIGRANTES, C. N. para la P. y D. de la P. M. y su F.-. (2017). Política nacional para la protección y desarrollo de la persona migrante salvadoreña y su familia, julio (CONMIGRANT).

Davis, J. H., & Chokshi, N. (2018). Trump defends ‘animals’ remark, saying it referred to MS-13 gang members. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/05/17/us/trump-animals-ms-13-gangs.html. Accessed 3 June 2020.

de Haas, H. (2010). Migration and Development: A theoretical perspective. International Migration Review, 44(1), 227–264. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-7379.2009.00804.x

Etling, A., Backeberg, L., & Tholen, J. (2020). The political dimension of young people’s migration intentions: Evidence from the Arab Mediterranean region. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 46(7), 1388–1404. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2018.1485093

FAO, O. de las N. U. para la A. y A.-, & PNUD, P. de las N. U. para el D.-. (2016). Seguridad Alimentaria y nutricional. Camino hacia del desarrollo humano. FAO & PNUD.

Fargues, P., & Fandrich, C. (2012). Migration after the arab spring. https://cadmus.eui.eu/bitstream/handle/1814/23504/MPCRR-2012-09.pdf?sequence=1. Accessed 20 June 2020.

Fernandez, B. (2010). Cheap and disposable? The impact of the global economic crisis on the migration of Ethiopian women domestic workers to the Gulf. Gender and Development, 18(2), 249–262. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552074.2010.491335

Finley, L., & Esposito, L. (2020). The immigrant as bogeyman: Examining Donald Trump and the right’s anti-immigrant, anti-PC rhetoric. Humanity and Society, 44(2), 178–197.

Fullerton, M. (2017). Trump, turmoil, and terrorism: The US immigration and refugee ban. International Journal of Refugee Law, 29(2), 327–338. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijrl/eex021

Fundación para la Educación Superior - FES. (2019). ¿ Irse ? ¿ Quedarse ? ¿ Volver ? Dinámicas migratorias y su efecto en la educación de los salvadoreños. FES y ESEN.

FUSADES, F. S. para el D. E. y S.-. (2020a). Impacto del COVID-19 en la pobreza en El Salvador. Nota de política pública No. 7 (Issue 7). FUSADES.

FUSADES, F. S. para el D. E. y S.-. (2020b). Informe de coyuntura económica. Noviembre 2020 (FUSADES).

Garrett, T. M. (2020). COVID-19, wall building, and the effects on migrant protection protocols by the Trump administration: The spectacle of the worsening human rights disaster on the Mexico-U.S. border. Administrative Theory & Praxis, 42(2), 240–248. https://doi.org/10.1080/10841806.2020.1750212

Greenaway, C., & Gushulak, B. (2017). Pandemics, migration and global health security. In P. Bourbeau (Ed.), Handbook on Migration and Security (pp. 316–338)). Edward Elgar Publishing. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781785360497

Guadagno, L. (2020). Migrants and the COVID-19 pandemic: An initial analysis. International Organization for Migration Geneva.

Halliday, T. (2006). Migration, risk, and liquidity constraints in El Salvador. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 54(4), 893–925. https://doi.org/10.1086/503584

Hazans, M. (2016). Migration experience of the baltic countries in the context of economic crisis. In Labor Migration, EU Enlargement, and the Great Recession (pp. 297–344). Springer Berlin Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-45320-9_13

Herm, A., & Poulain, M. (2012). Economic crisis and international migration. What the EU data reveal? Revue Européenne des Migrations Internationales, 28(4), 145–169.

Hiskey, J., Montalvo, J. D., & Orcés, D. (2014). Democracy, governance, and emigration intentions in Latin America and the Caribbean. Studies in Comparative International Development, 49(1), 89–111. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12116-014-9150-6

IMF, I. M. F.-. (2020). World economic outlook: A long and difficult ascent. International Monetary Fund Washington, DC.

Instituto Universitario de Opinión Pública. (2021). La población salvadoreña evalúa el segundo año de Gobierno del presidente Nayib Bukele. IUDOP.

International Organisation for Migrations- IOM. (2019). World migration report 2020. IOM. https://publications.iom.int/books/world-migration-report-2020. Accessed 15 June 2020.

International Organization for Migration. (2019). Glossary on migration. IOM.

IOM, International Organisation for Migrations -. (2017). Encuesta Nacional de Migración y Remesas El Salvador 2017. IOM.

IOM, International organisation for migrations-. (2020). Effects of COVID -19 on Migrants Main Findings (Issue June). IOM.

IOM, International Organisation for Migrations-, & World Food Program - WFP. (2020). Populations at risk : Implications of COVID-19 for hunger , migration and displacement (I. WFP (ed.); Issue November).

Keller, A. S., & Wagner, B. D. (2020). COVID-19 and immigration detention in the USA: Time to act. The Lancet Public Health, 5(5), e245–e246. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30081-5

Khan, K., Arino, J., Hu, W., Raposo, P., Sears, J., Calderon, F., Heidebrecht, C., Macdonald, M., Liauw, J., Chan, A., & Gardam, M. (2009). Spread of a novel influenza A (H1N1) virus via global airline transportation. New England Journal of Medicine, 361(2), 212–214. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMc0904559

King, R. (2012). Theories and typologies of migration: An overview and a primer (Willy Brandt Series of Working Papers in International Migration and Ethnic Relations 3/12). Malmö: Malmö University.

Lafleur, J.-M., & Stanek, M. (2017). Lessons from the South-north migration of EU citizens in times of crisis (Spring Nat, pp. 215–224). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-39763-4_12

Loureiro, P. R. A., & Silva, E. C. D. (2010). Does violence deter investment, hinder economic growth? Brazilian Review of Econometrics, 30(1), 53. https://doi.org/10.12660/bre.v30n12010.3500

Lundquist, J. H., & Massey, D. S. (2005). Politics or economics? International migration during the Nicaraguan Contra War. Journal of Latin American Studies, 37(1), 29–53. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022216X04008594

Marchand, M. H. (2021). The caravanas de migrantes making their way north: Problematising the biopolitics of mobilities in Mexico. Third World Quarterly, 42(1), 141–161. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2020.1824579

Marchiori, L., Maystadt, J.-F., & Schumacher, I. (2012). The impact of weather anomalies on migration in sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 63(3), 355–374. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeem.2012.02.001

Marques, J. C., & Góis, P. (2017). Structural emigration: The revival of Portuguese outflows. In South-North migration of EU Citizens in times of crisis (pp. 65–82). Springer.

Martínez, O. (2014). Asesinaron al Niño de Hollywood (y todos sabíamos que eso ocurriría). El Faro. https://salanegra.elfaro.net/es/201411/cronicas/16293/asesinaron-al-niño-de-hollywood-(y-todos-sabíamos-que-eso-ocurriría).htm. Accessed 15 June 2020.

Martínez, C. (2021). ¿ DE QUÉ HUYEN LAS CARAVANAS ? Revista de La Universidad de México, 869(1), 126–130.

Mayda, A. M. (2010). International migration: A panel data analysis of the determinants of bilateral flows. Journal of Population Economics, 23(4), 1249–1274. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-009-0251-x

Mendoza, C. (2018). How Trump’s land of the free turned into the home of the cages for immigrant families seeking asylum. Pub. Int. L. Rep., 24, 73.

Monico, C., Rotabi, K. S., & Lee, J. (2019). Forced child–family separations in the southwestern U.S. border under the “zero-tolerance” policy: Preventing human rights violations and child abduction into adoption (part 1). Journal of Human Rights and Social Work, 4(3), 164–179. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41134-019-0089-4

Nawrotzki, R. J., Riosmena, F., & Hunter, L. M. (2013). Do rainfall deficits predict U.S.-bound migration from rural Mexico? Evidence from the Mexican census. Population Research and Policy Review, 32(1), 129–158. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-012-9251-8

O. for E. C. and Development. (2021). International migration outlook 2020. OECD.

Obinna, D. N. (2019). Transiciones e Incertidumbres: Migration from El Salvador, Honduras and Guatemala. Latino Studies, 17(4), 484–504. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41276-019-00209-8

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2014). International migration outlook 2014. OECD. https://doi.org/10.1787/migr_outlook-2014-en.

Organización Internacional para las Migraciones. (2020). El Salvador- Encuesta de medios de vida a población migrante retornada en El Salvador en el marco del COVID-19. Ronda 2. OIM.

Organización Internacional para las Migraciones. (2021). Tendencias migratorias en Centroamérica, Norteamérica y El Caribe - Agosto 2021. OIM.

Parella Rubio, S., & Petroff, A. (2014). Voluntary return programmes in Bolivia and Spain in the context of crisis Olga Serradell Pumareda. Afers Internacionals, 171–192. www.cidob.org. Accessed 15 June 2020.

Parella, S., Petroff, A., Piqueras, C., & Speroni, T. (2017). Employment crisis in Spain and return migration of Bolivians : An overview (Issue 34). https://repositori.upf.edu/bitstream/handle/10230/33595/GRITIMWP 34.pdf. Accessed 15 June 2020.

Pew Research Center. (2020). Facts on U.S. immigrants, 2018. https://www.pewresearch.org/hispanic/2020/08/20/facts-on-u-s-immigrants-current-data/. Accessed 10 June 2020.

Programa de las Naciones Unidas para el Desarrollo, & Organización Internacional para las Migraciones. (2021). Impacto del COVID-19 en hogares con personas migrantes en la Unión, El Salvador. PNUD & OIM.

Romero-Valiente, J. M. (2018). Causas de la emigración española actual: la “movilidad exterior” y la incidencia de la crisis económica. Boletín de La Asociación de Geógrafos Españoles, 76, 303. https://doi.org/10.21138/bage.2524

Rubin, J., & Wagner, R. (2015). Destroying collateral: Asset security and the financing of firms. Applied Economics Letters, 22(9), 704–709. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504851.2014.969823

Sandoval, C. (2020). Centroamérica desgarrada : demandas y expectativas de jóvenes residentes en colonias empobrecidas. Consejo Latinoamericano de Ciencias Sociales.

Schon, J. (2019). Motivation and opportunity for conflict-induced migration: An analysis of Syrian migration timing. Journal of Peace Research, 56(1), 12–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343318806044

Scribner, T. (2017). You are not welcome here anymore: Restoring support for refugee resettlement in the age of Trump. Journal on Migration and Human Security, 5(2), 263–284. https://doi.org/10.1177/233150241700500203

Security, D. of H. (2019). Yearbook of Immigration Statistics 2019. https://www.dhs.gov/immigration-statistics/yearbook/2019. Accessed 10 June 2020.

Semple, K., & Wirtz, N. (2021). Migrant caravan, now in Guatemala, tests regional resolve to control migration. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/17/world/americas/migrant-caravan-us-biden-guatemala-immigration.html. Accessed 21 July 2021.

Serneels, P., & Verpoorten, M. (2015). The impact of armed conflict on economic performance. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 59(4), 555–592. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002713515409

Simon, M., Schwartz, C., & Hudson, D. (2022). COVID-19 insecurities and migration aspirations. International Interactions, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050629.2022.1991919

Tilly, C. (2011). The impact of the economic crisis on international migration: A review. Work, Employment and Society, 25(4), 675–692. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017011421799

Tintori, G., & Romei, V. (2017). Emigration from Italy after the crisis: The shortcomings of the brain drain narrative. In South-North migration of EU citizens in times of crisis (pp. 49–64). Springer.

Tjaden, J., Auer, D., & Laczko, F. (2019). Linking migration intentions with flows: Evidence and potential use. International Migration, 57(1), 36–57. https://doi.org/10.1111/imig.12502

U.S Custom and Border Patrol. (2021). Southwest Land Border Encounters. Demographics for U.S. border patrol (USBP) and office of field operations (OFO) include: https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/southwest-land-border-encounters. Accessed 21 July 2021.

Valencia, R. (2011). Yo violada. El Faro. https://salanegra.elfaro.net/es/201107/cronicas/4922/Yo-violada.htm. Accessed 20 June 2020.

van Dalen, H. P., & Henkens, K. (2008). Emigration intentions: Mere words or true plans? Explaining international migration intentions and behavior. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1153985

Vanderbilt University. (2021). El Salvador year of study: 2021. https://www.vanderbilt.edu/lapop/el-salvador.php. Accessed 15 June 2020.

Villa-Torres, L., González-Vázquez, T., Fleming, P. J., González-González, E. L., Infante-**bille, C., Chavez, R., & Barrington, C. (2017). Transnationalism and health: A systematic literature review on the use of transnationalism in the study of the health practices and behaviors of migrants. Social Science & Medicine, 183, 70–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.04.048

Voice of America. (2021). Reportan cifra récord de migrantes salvadoreños detenidos en la frontera sur de EE. UU. en 2021. Voice of America. https://www.vozdeamerica.com/a/cbp-reporta-record-salvadorenos-detenidos-en-frontera-eeuu-2021/6285119.html. Accessed 25 July 2021.

Wanner, P. (2021). Can Migrants’ Emigration intentions predict their actual behaviors? Evidence from a Swiss survey. Journal of International Migration and Integration, 22(3), 1151–1179. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-020-00798-7

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Manuscript was independently drafted in mid-2020. The views expressed are personal and may not reflect opinions of organizations associated with the author.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Durán, C.A. Intention to Migrate Due to COVID-19: a Study for El Salvador. Int. Migration & Integration 24, 349–368 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-022-00952-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-022-00952-3