Abstract

This study examines the association between sexual desire and sexual satisfaction in sexual double standard typologies (i.e., egalitarian, man-favorable and woman-favorable) in the sexual freedom and sexual shyness areas. The sexual double standard (SDS), sexual desire (partner-focused dyadic, dyadic for an attractive person, and solitary) and sexual satisfaction were assessed in 444 men and 499 heterosexual women with a partner (M = 37.33; SD = 12.09). The results showed that dyadic sexual desire toward a partner was the main positive predictor of sexual satisfaction for men and women in all the SDS typologies, and in both the sexual freedom and sexual shyness areas. Solitary sexual desire was negatively associated with sexual satisfaction in men and women adhered to the woman-favorable SDS typology, and in men in the egalitarian typology in the sexual shyness area. Sexual desire for an attractive person showed no relation with sexual satisfaction. In conclusion, the importance of the SDS in relating sexual desire and sexual satisfaction in men and women is highlighted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Sexual health implies physical, mental and social well-being in relation to sexuality (World Health Organization, 2018). In this context, sexual functioning is a fundamental dimension of sexual health (Fielder, 2013) that is based on consistence (or deviation) of the sexual response in relation to some proposed sexual norms that are influenced by theoretical, empirical and cultural matters (Giraldi et al., 2014). Sexual satisfaction dimensions stand out when considering the last stage of the sexual response cycle (Carrobles & Sanz, 1991; Sierra & Buela-Casal, 2004). Its conceptualisation reflects the degree of well-being and fulfilment experienced in sexual activity (Carrobles & Sanz, 1991). In this sense, “the right of all persons to pursue a satisfying, safe and pleasurable sexual life” is recognised (World Health Organization, 2010, p. 10). The World Association for Sexual Health (2014) also proposes this right as part of sexual rights, affirming the right to the highest attainable standard of health, which encompasses sexual health. This includes the opportunity for pleasurable, satisfying, and safe sexual experiences. It is also a key factor for quality of life and general well-being (Fielder, 2013; Henderson et al., 2009; Sánchez-Fuentes et al., 2014). In the sexual relationships area, it has been defined as “an affective response arising from one’s subjective evaluation of the positive and negative dimensions associated with one’s sexual relationship” (Lawrance & Byers, 1995, p. 268).

Sexual satisfaction can be associated with difficulties in different phases of the human sexual response cycle (Laumann et al., 1999). In line with this, sexual desire stands out for the high prevalence of the dysfunctions related to it in both men and women (American Psychiatric Association, 2022), and is a significant predictor of sexual satisfaction (Chao et al., 2011; Park & MacDonald, 2022; Peixoto, 2019, 2022; Sánchez-Fuentes et al., 2014). Sexual desire refers to the interest that someone shows in sexual activity either alone or as a couple and is quantified by the thoughts that motivate seeking sexual opportunities or being receptive to them (Spector et al., 1996). Thus difficulties in sexual desire have been found to be negatively associated with sexual satisfaction (Chao et al., 2011; Park & MacDonald, 2022; Peixoto, 2019, 2022; Sánchez-Fuentes et al., 2014). Spector et al. (1996) proposed two dimensions of sexual desire: dyadic, referring to interest in participating in sexual relationships with someone else, including intimacy and desire of sharing with other people; solitary, referring to interest in participating in sexual activity with oneself. Subsequently, Moyano et al. (2016) extended this proposal to a tridimensional model in which dyadic sexual desire is divided into sexual desire to a partner and sexual desire to an attractive person. So in the couple relationships context, sexual desire can include three dimensions: dyadic to partner, dyadic to an attractive person and solitary. Previous evidence has shown that partner-focused dyadic sexual desire is positively associated with sexual satisfaction, whereas dyadic sexual desire for an attractive person or solitary sexual desire are negatively associated in men, with no association in women (Moyano et al., 2016; Peixoto, 2019).

Of the sexual attitudes related to sexual satisfaction (Álvarez-Muelas et al., 2020, 2021a, 2023) and sexual desire (Álvarez-Muelas et al., 2020), the sexual double standard (SDS) is included. The SDS involves different criteria for evaluating sexual behavior depending on if it is performed by a man or a woman (Milhausen & Herold, 2002; Sagebin & Mara, 2013). Research indicates stricter standards for women than for men when they define their sexual behavior as appropriate or inappropriate (Foschi, 2000). Men are expected to be more sexually active, dominant and start sexual activity, while women are sexually more reactive, submissive, and passive (Endendijk et al., 2020). In agreement with traditional gender norms, this sexual attitude has been identified in behaviors like having premarital/extramarital sex (Savas & Yol, 2023) or the sexual consent area (Moyano et al., 2022; Rollero et al., 2023). The SDS study is highlighted because of its implications for men and women’s sexual health and dimensions, such as sexual functioning (see Álvarez-Muelas et al., 2020). The presence of a SDS attitude more in favor of man than woman has been negatively associated with sexual functioning, less sexual desire in women (Jackson & Cram, 2003; Kelly et al., 2016), and less sexual satisfaction in men and women (Álvarez-Muelas et al., 2021a, 2023; Haavio-Mannila & Kontula, 2003; Horne & Zimmer-Gembeck, 2006; Santos-Iglesias et al., 2009). In addition, a 10% increase in sexual aggression toward women has been observed in men with a man-favorable SDS typology (Vílchez-Jaén et al., 2022).

The SDS has been measured regarding sexual behavior in relation to exercising sexual freedom, which refers to the recognition and approval of having freely sexual relationships while respecting sexual rights (Álvarez-Muelas et al., 2021b), which have been traditionally more positively valued in men (Gómez-Berrocal et al., 2022). Recently, and possibly because of awareness of sexual violence and women’s further empowerment in society (Kettrey, 2016; Tiefer, 2001) when considering that the sexual proactivity of men could pose a risk to their sexual health (Milhausen & Herold, 2002), a reverse SDS to its traditional version has emerged; that is, it is favorable for women. This reverse sexual double standard implies the advocacy for greater sexual freedom for women than for men (Milhausen & Herold, 2002), that is to say, the approval of behaviors that involve the exercise of sexual freedom (e.g., hookup culture, number of sexual partners; see Hensums et al., 2022; Kettrey, 2016). Examples of behaviors that reflect this reverse sexual double standard can be found in the Spanish validation of the Sexual Double Standard Scale (see Sierra et al., 2018): “It’s okay for a woman to have more than one sexual relationship at the same time” or “It’s okay for a woman to have sex with a man she is not in love with”.

In recent years, a sexual script that tends to represent a more conservative conception of sexuality by defending more sexual inhibition or shyness has emerged (Sakaluk et al., 2013). Sexual shyness is defined as demonstration of decorum, chastity and continence in sexual relationships (Álvarez-Muelas et al., 2021b). In line with traditional gender norms, sexual shyness would be seen more appropriate for women (Fasula et al., 2014). According to these two areas of sexual behaviors and different ways this sex attitude is shown, Álvarez-Muelas et al. (2021b) propose evaluating different SDS adherence typologies (i.e., man-favorable, woman-favorable and egalitarian) in two sexual behavior areas: sexual freedom and sexual shyness. The man-favorable SDS typology defends greater sexual freedom for men/greater sexual shyness for women; the women-favorable SDS typology formulates greater sexual freedom for women/greater sexual shyness for men; finally, the egalitarian typology defends the same criteria for evaluating sexual behavior in men and women (Álvarez-Muelas et al., 2021b; Gómez-Berrocal et al., 2022). In the Spanish sample, a higher percentage of men are identified as supporting the man-favorable SDS typology, while women tend to lean toward egalitarian and woman-favorable SDS typologies (Álvarez-Muelas et al., 2021b). Furthermore, in general, the man-favorable SDS typology appears to be observed in middle-aged men in the sexual freedom area and in older groups of women for both sexual areas. In contrast, the woman-favorable typology prevails in younger samples in the sexual freedom area (Álvarez-Muelas et al., 2021b).

By taking into account the relationship between sexual desire and sexual satisfaction, considering the impact of SDS on these two dimensions of sexual functioning, the main objective of this study is to examine the relation of sexual desire with sexual satisfaction in people with a heterosexual partner with different SDS adherence typologies. This study aims to thoroughly understand the significance of a gender-based prejudice sexual attitude on sexual response. Based on the observed differences in sexual desire and sexual satisfaction among SDS adherence type (Álvarez-Muelas et al., 2021a, 2023; Haavio-Mannila & Kontula, 2003; Horne & Zimmer-Gembeck, 2006; Jackson & Cram, 2003; Kelly et al., 2016; Santos-Iglesias et al., 2009), this research hypothesizes differences in the association between the three types of sexual desire (i.e., partner-focused dyadic, dyadic for an attractive person and solitary) and sexual satisfaction according to the SDS adherence typology (i.e., egalitarian, man-favorable, woman-favorable) in the areas of sexual freedom and sexual shyness.

Method

Participants

The sample, obtained through incidental sampling, consisted of 943 participants (444 men and 499 women) aged between 18 and 75 years old (M = 37.33; SD = 12.09). The inclusion criteria were: (a) Spanish nationality, (b) aged 18 years of older; (c) in a heterosexual couple relationship. Table 1 includes the participants’ socio-demographic characteristics.

Instruments

The Socio-Demographic and Sexual History Questionnaire. It collects socio-demographic information about sex, age, level of education, nationality, sexual orientation, relationship (yes/no) and information about the relationship (sex and age of the partner and duration of the relationship), together with information about sexual history referring to sexual relationships (experience of sexual relationships, age of first sexual relationships and number of sexual partners) and masturbation experience (experience of solitary masturbation and age of first masturbation).

The Spanish Version of the Sexual Double Standard Scale (SDSS; Muehlenhard & Quackenbush, 2011) by Sierra et al. (2018). It includes two factors (Acceptance of sexual freedom [SF] and Acceptance of sexual shyness [SS]), consisting of four pairs of items written in parallel to represent the same sexual behavior performed by the man and the woman (e.g., A woman who initiates sex is too aggressive / A man who initiates sex is too aggressive). They are answered on a 4-point Likert-type scale (0 = strongly disagree, 3 = strongly agree). The scores of both factors allow the Index of Double Standard for Sexual Freedom scores (IDS-SF) and the Index of Double Standard for Sexual Shyness scores (IDS-SS) to be obtained. These indices are acquired by subtracting scores between the pairs of items comprising it. They represent a bipolar measure with scores ranging from − 12 to + 12. Positive scores in the index (+ 1 to + 12) define the man-favorable SDS typology, negative scores (− 1 to − 12) denote the woman-favorable SDS typology, and a score equaling zero in the subtraction of each pairs refers to the egalitarian typology. The scores of both factors present adequate psychometric properties (Sierra et al., 2018). In this study, Cronbach's alpha values for both men and women are above 0.75.

The Spanish Version of the Sexual Desire Inventory (Spector et al., 1996) by Moyano et al. (2016). It assesses three types of sexual desire: partner-focused dyadic, dyadic for an attractive person and solitary. It consists of 13 items (e.g., How strong is your desire to engage in sexual activity with a partner? or How strong is your desire to engage in sexual behavior by yourself?) answered on a Likert-type scale with different formats depending on the item. It presents good psychometric properties (Moyano et al., 2016). The Cronbach's alpha values obtained in this study were above 0.75 in all cases.

The Spanish Version of the Global Measure of Sexual Satisfaction (GMSEX; Lawrance & Byers, 1995) by Sánchez-Fuentes et al. (2015). It evaluates overall sexual satisfaction in the couple's relationship. It consists of five items with a seven-point bipolar response scale (good-bad, pleasant-unpleasant, positive–negative, satisfying-unsatisfying, valuable-worthless). Scores range from 5 to 35 points, with higher scores corresponding to greater sexual satisfaction. The GMSEX scores present good indicators of reliability and validity (Sánchez-Fuentes et al., 2015). In this study, Cronbach's alpha is 0.93 for men and 0.92 for women.

Procedure

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee on Human Research of the University of Granada (n. 682/CEIH/2018). An online battery of instruments, created with LimeSurvey software and distributed through various virtual platforms (Facebook®, Twitter®, WhatsApp® and email), was used. Participation in the study was voluntary and unpaid. To participate, the informed consent form had to be read and accepted, which specified the overall study objective. Anonymity and data confidentiality were guaranteed. Automatic responses were avoided by using a CAPTCHA (a security question consisting of a simple random arithmetic operation) and three control items.

Data Analysis

First, the scores on both the SDS indices (IDS-SF and IDS-SS) were compared between men and women using a Student's t-test. As significant differences were identified for the sexual freedom (IDS-SF; t = 1.93; p = 0.05) and sexual shyness (IDS-SS; t = 4.51; p < 0.001) areas, analyses were conducted separately for men and women. Next linear regression models were performed using the Introduce method to explain the variance of sexual satisfaction from age, partner-focused dyadic sexual desire, dyadic sexual desire toward an attractive person, and solitary sexual desire in all three SDS adherence typologies of the sexual freedom and sexual shyness areas. The R® program (version 3.6.3) with the Rstudio® interface (version 1.2.5042) was used to impute missing values. The rest of the statistical analyses were performed with the IBM® SPSS® Statistics software (version 22).

Results

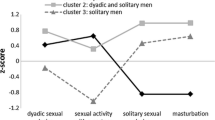

For men in the sexual freedom area, it was observed that, in those with the egalitarian typology, 19% of the variance of sexual satisfaction (F (4, 193) = 12.89; p < 0.001) was explained negatively by age (β = − 0.15) and positively by partner-focused dyadic sexual desire (β = 0.40). In the man-favorable SDS typology, the model explained up to 16% of the variance in sexual satisfaction (F (4, 64) = 4.24; p = 0.004) from partner-focused dyadic sexual desire as the only predictor variable (β = 0.37). In the woman-favorable SDS typology, 11% of the variance in sexual satisfaction (F (4, 158) = 6.02; p < 0.001) was explained by partner-focused dyadic sexual desire in the positive direction (β = 0.25) and solitary sexual desire in the negative sense (β = − 0.20). In the sexual shyness area, for the men with the egalitarian typology, 22% of the variance in sexual satisfaction was explained by age (β = − 1.15) and solitary sexual desire (β = − 0.14) in the negative sense, and by partner-focused dyadic sexual desire in the positive sense (β = 0.41) (F(4, 215) = 16.62; p < 0.001). In the man-favorable SDS (F (4, 88) = 3.67; p = 0.008) and woman-favorable SDS (F (4, 107) = 4.51; p = 0.002) typologies, the only predictor variable was partner-focused dyadic sexual desire (β = 0.30; β = 0.31), which explained 10% and 11% of the variance in sexual satisfaction, respectively. See Table 2.

For women in the sexual freedom area, those with the egalitarian typology (F (4, 225) = 24.37; p < 0.001) and the man-favorable SDS typology (F (4, 46) = 9.89; p < 0.001), 29% and 42% of the variance in sexual satisfaction was respectively explained by partner-focused dyadic sexual desire in the positive sense (β = 0.55; β = 0.67). In the woman-favorable SDS typology, 44% of the variance in sexual satisfaction (F (4, 199) = 40.71; p < 0.001) was explained by partner-focused dyadic sexual desire in the positive sense (β = 0.69) and solitary sexual desire in the negative sense (β = − 0.14). In the sexual shyness area, the only variable with explanatory capacity for the variance of sexual satisfaction was partner-focused dyadic sexual desire in the positive sense, which explained 27% of the model in the egalitarian typology (F (4, 247) = 24. 01; p < 0.001; β = 0.54), 48% in the man-favorable SDS typology (F (4, 46) = 12.56; p < 0.001; β = 0.72) and 47% in the woman-favorable SDS typology (F (4, 159) = 37.13; p < 0.001; β = 0.70). See Table 3.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to examine the association between sexual desire (i.e., partner-focused dyadic, attractive person-focused dyadic, solitary) and sexual satisfaction in people with a heterosexual partner who shows different SDS adherence typologies (i.e., egalitarian, man-favorable, woman-favorable) for the sexual freedom and sexual shyness areas. As far as the authors are aware, no previous studies have analysed the relationship of the three sexual desire dimensions, proposed by Moyano et al. (2016), and sexual satisfaction by taking into account a gender-based prejudice sexual attitude, such as the SDS. The results obtained confirm the hypothesis of this study by revealing that the SDS adherence typology in the sexual freedom and sexual shyness areas has an implication for the relationship between sexual desire and sexual satisfaction of men and women in heterosexual relationships.

The positive association of partner-focused dyadic sexual desire with sexual satisfaction in the three SDS adherence typologies (i.e., egalitarian, man-favorable, woman-favorable) is first highlighted for sexual freedom and sexual shyness. In both men and women, greater partner-focused dyadic sexual desire is associated with higher sexual satisfaction in the romantic relationship context. As previously noted by Moyano et al. (2016) and Peixoto (2019), this result was expected and underscores the significance of partner-focused dyadic sexual desire for sexual satisfaction with the partner. Furthermore, this finding is congruent with previous evidence to suggest that the socio-emotional aspects of the relationship may be among the most relevant factors for understanding sexual satisfaction (Parish et al., 2007). Specifically in women, this type of desire was the primary variable with explanatory capacity for the variance in sexual satisfaction, which is consistent with previous evidence showing that they often evaluate their sexual satisfaction by considering that of their partners (McClelland, 2011; Pascoal et al., 2014; Sánchez-Fuentes & Santos-Iglesias, 2016; Vowels et al., 2022).

It is also worth mentioning that partner-focused dyadic sexual desire was the only variable to be significantly associated with sexual satisfaction in men and women with a man-favorable SDS adherence typology for both the sexual freedom and shyness areas. The type of SDS that approves greater sexual freedom for men/greater sexual shyness for women is consistent with the traditional sexual script that assigns men a proactive attitude for initiating sexual encounters, and showing more willingness, knowledge, and skills in sexual relationships, while for women an emotional, submissive and passive orientation in sex is expected (Endendijk et al., 2020; Sakaluk et al., 2013). The traditional sexual script is characterized by being heteronormative and gendered (Sakaluk et al., 2013), which could emphasize the role of partner-focused dyadic sexual desire in the man-favorable typology.

Second, a negative association appeared between solitary sexual desire and sexual satisfaction in men and women with a woman-favorable typology in the sexual freedom area, and in men with an egalitarian typology in the sexual shyness area. A higher frequency of masturbation, a behavior closely associated with solitary sexual desire (Cervilla et al., 2023), may be associated with difficulties in sexual functioning and less sexual satisfaction with a partner (Brody & Costa, 2009; Kontula & Miettinen, 2016). In this regard, the compensatory model has been proposed to explain the negative relationship between masturbation and sexual satisfaction by considering that masturbation is practiced as a substitute for sexual relationships with a partner due to the inability to maintain such relationships or to be dissatisfied with them (Regnerus et al., 2017). In contrast, the complementary model supports a positive association between masturbation and sexual satisfaction (Regnerus et al., 2017). Previous findings point out that the compensatory model could be more associated in men and the complementary model would be evidenced more with women (Fischer & Træen, 2022). Nevertheless, our results demonstrate independence of gender in the compensatory or complementary role of masturbation (Das et al., 2009). The negative relationship between solitary sexual desire and satisfaction has been observed in the SDS woman-favorable typology. In men with an SDS attitude that favors their own sexual inhibition and encourages women's proactivity and willingness to initiate sexual encounters, masturbation could be a compensatory measure of not satisfactorily fulfilling their unmet expectations. For a woman who takes this SDS attitude, in which her dominance in sexual relations prevails, masturbation may be a substitute for dissatisfaction during sexual activity with her partner when the responsibility of having an orgasm is mainly hers. The negative relationship between solitary sexual desire and sexual satisfaction has also been observed in men with an egalitarian typology in the sexual shyness area. While more egalitarian attitudes in evaluating the sexual behaviors of men and women are expected in societies that value sexual freedom, the sexual shyness area could more subtly represent prejudice, for which less research is available (Gómez-Berrocal et al., 2022). A person with an egalitarian typology for sexual shyness would defend the same criteria for evaluating behaviors related to sexual inhibition in both men and women. However, it could manifest their approval of showing sexual inhibition. Therefore, there is a need for more in-depth studies of adherence to different SDS typologies in behaviors related to this sexual behavior area (Gómez-Berrocal et al., 2022). For example, by considering the intensity of defending sexual inhibition in relation to solitary sexual desire and masturbation behavior.

Finally, it is worth noting that significant relationships are lacking between attractive person-focused dyadic sexual desire and sexual satisfaction. This finding falls in line with the results of Moyano et al. (2016), who observed that while partner-focused dyadic sexual desire is strongly associated with sexual satisfaction, desire for an attractive person does not play a significant role. Once again, this confirms the importance of partner-focused sexual desire in the study of sexual satisfaction in a romantic relationship context, where the emotional aspects are key (Sakaluk et al., 2013).

This study has limitations that should be considered when generalizing the results. More than half of the participants have completed university education, which is known to be associated with SDS (Sierra et al., 2018). Another limitation is the study of sexual satisfaction in a couple relationship context by considering only individual perspectives. It would be interesting for future research to study the dyad and include other characteristics of the relationship, such as its duration, cohabitation status, whether or not there are children, the possibility of intimacy or the presence of physical barriers, the use of contraceptives, or occupational factors, because these variables can impact satisfaction in a couple relationship (Sánchez-Fuentes et al., 2014).

It is important to consider the implications of this study. The significant relevance of the Sexual Double Standard (SDS) in the connection between sexual desire and sexual satisfaction underscores the necessity of considering sexual attitudes in the exploration of sexual functioning (Sierra et al., 2021). Furthermore, sexual attitudes may play a crucial role in the field of sexual therapy, particularly within the context of couples. This is especially true given the high prevalence of challenges related to sexual desire (Parish & Hahn, 2016) and the importance of sexual satisfaction (Fallis et al., 2016). Therefore, having evidence that delves into the understanding of the interrelations between sexual attitudes is essential for an enhanced approach to addressing sexual difficulties in couples. In particular, this research highlights that in the association between sexual desire and satisfaction, a sexual attitude based on gender bias, such as the SDS, stands out. Its presence mediates the implication of sexual desire types in the sexual satisfaction of both men and women. Likewise, the results underscore the need to enhance educational programs by incorporating a gender perspective. The effectiveness of sexual education programs is increased when including a gender perspective, specifically addressing the sexual double standard (Ubillos-Landa et al., 2021). Therefore, this research encourages the consideration of this sexual attitude to promote a healthy and enjoyable sexuality, free from the inequality of sexual behaviors between men and women.

In conclusion, this study examines the relationship among partner-focused dyadic sexual desire, attractive person-focused dyadic sexual desire, solitary sexual desire and sexual satisfaction according to sexual attitude based on gender prejudice, such as the SDS. The results lead to the conclusion that the SDS attitude can act as a significant variable in the relationship between desire and sexual satisfaction. Furthermore, the obtained results support the three-dimensional model of sexual desire described by Moyano et al. (2016) by confirming the relative independence of the three types of sexual desire. The positive association between partner-focused dyadic sexual desire and sexual satisfaction in both men and women particularly stands out, while solitary sexual desire is negatively related to sexual satisfaction in individuals with SDS adherence typologies that have emerged from new sexual scripts (i.e., woman-favorable and egalitarian).

Data Availability

The datasets generated by the survey research are available in https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.24574756.v1.

References

Álvarez-Muelas, A., Gómez-Berrocal, C., & Sierra, J. C. (2020). Relationship of sexual double standard with sexual functioning and risk sexual behaviors: A systematic review. Revista Iberoamericana de Psicología y Salud, 11, 103–116. https://doi.org/10.23923/j.rips.2020.02.038

Álvarez-Muelas, A., Gómez-Berrocal, C., & Sierra, J. C. (2021a). Study of sexual satisfaction in different typologies of adherence to the sexual double standard. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 609571. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.609571

Álvarez-Muelas, A., Gómez-Berrocal, C., & Sierra, J. C. (2021b). Typologies of sexual double standard adherence in Spanish population. The European Journal of Psychology Applied to Legal Context, 13, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.5093/ejpalc2021a1

Álvarez-Muelas, A., Mateo, V., & Sierra, J. C. (2023). Comparison of the components of the interpersonal exchange model of sexual satisfaction between different typologies of adherence to the sexual double standard. Revista Iberoamericana de Psicología y Salud, 14, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.23923/j.rips.2023.01.060

American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Fifth Edition. Text Revision (DSM-5-TR). Author.

Brody, S., & Costa, R. M. (2009). Satisfaction (sexual, life, relationship, and mental health) is associated directly with penile-vaginal intercourse, but inversely with other sexual behavior frequencies. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 6, 1947–1954. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01303.x

Carrobles, J. A., & Sanz, A. (1991). Terapia sexual. Fundación Universidad-Empresa.

Cervilla, O., Jiménez-Antón, E., Álvarez-Muelas, A., Mangas, P., Granados, R., & Sierra, J. C. (2023). Solitary sexual desire: Its relation to subjective orgasm experience and sexual arousal in the masturbation context within a Spanish population. Healthcare, 11, 805. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11060805

Chao, J. K., Lin, Y. C., Ma, M. C., Lai, D. J., Ku, Y. C., Kuo, W. H., & Chao, I. C. (2011). Relationship among sexual desire, sexual satisfaction, and quality of life in middle-aged and older adults. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 37, 386–403. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2011.607051

Das, A., Parish, W. L., & Laumann, E. O. (2009). Masturbation in urban China. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 38, 108–120. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-007-9222-z

Endendijk, J. J., van Baar, A. L., & Deković, M. (2020). He is a stud, she is a slut! A meta-analysis on the continued existence of sexual double standards. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 24, 163–190. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868319891310

Fallis, E. E., Rehman, U. S., Woody, E. Z., & Purdon, C. (2016). The longitudinal association of relationship satisfaction and sexual satisfaction in long-term relationships. Journal of Family Psychology, 30, 822–831. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000205

Fasula, A. M., Carry, M., & Miller, K. S. (2014). A multidimensional framework for the meanings of the sexual double standard and its application for the sexual health of young black women in the U.S. Journal of Sex Research, 51, 170–183. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2012.716874

Fielder, R. (2013). Sexual functioning. In M. D. Gellman & J. R. Turner (Eds.), Encyclopedia of behavioral medicine (pp. 1774–1777). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-1005-9_668

Fischer, N., & Træen, B. (2022). A seemingly paradoxical relationship between masturbation frequency and sexual satisfaction. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 51, 3151–3167. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-022-02305-8

Foschi, M. (2000). Double standards for competence: Theory and research. Annual Review of Sociology, 26, 21–42. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.26.1.21

Giraldi, A., Kristensen, E., & Sand, M. (2014). Endorsement of models describing sexual response of men and women with a sexual partner: An online survey in a population sample of Danish adults ages 20–65 years. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 12, 116–128. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsm.12720

Gómez-Berrocal, C., Moyano, N., Álvarez-Muelas, A., & Sierra, J. C. (2022). Sexual double standard: A gender-based prejudice referring to sexual freedom and sexual shyness. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 1006675. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1006675

Haavio-Mannila, E., & Kontula, O. (2003). Single and double sexual standards in Finland, Estonia and St. Petersburg. Journal of Sex Research, 40, 36–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224490309552165

Henderson, A. W., Lehavot, K., & Simoni, J. M. (2009). Ecological models of sexual satisfaction among lesbian/bisexual and heterosexual women. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 38, 50–65. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-008-9384-3

Hensums, M., Overbeek, G. Y., & Jorgensen, T. D. (2022). Not one sexual double standard but two? Adolescents’ attitudes about appropriate sexual behavior. Youth and Society, 54, 23–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X20957924

Horne, S., & Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J. (2006). The female sexual subjectivity inventory: Development and validation of a multidimensional inventory for late adolescents and emerging adults. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 30, 125–138. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.2006.00276.x

Jackson, S. M., & Cram, F. (2003). Disrupting the sexual double standard: Young women´s talk about heterosexuality. British Journal of Social Psychology, 42, 113–127. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466603763276153

Kelly, M., Inoue, K., Barratt, A., Bateson, D., Rutherford, A., & Richters, J. (2016). Performing (heterosexual) femininity: Female agency and role in sexual life and contraceptive use—A qualitive study in Australia. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 19, 240–255. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2016.1214872

Kettrey, H. H. (2016). What´s gender got to do with it? Sexual double standards and power in heterosexual colleague hookups. Journal of Sex Research, 53, 754–765. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2016.1145181

Kontula, O., & Miettinen, A. (2016). Determinants of female sexual orgasms. Socioaffective Neuroscience & Psychology, 6, 31624. https://doi.org/10.3402/snp.v6.31624

Laumann, E. O., Paik, A., & Rosen, E. C. (1999). Sexual dysfunction in the United States: Prevalence and predictors. JAMA, 281, 537–544. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.281.6.537

Lawrance, K. A., & Byers, E. S. (1995). Sexual satisfaction in long-term heterosexual relationships: The interpersonal exchange model of sexual satisfaction. Personal Relationships, 2, 267–285. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6811.1995.tb00092.x

McClelland, S. I. (2011). Who is the ‘“self”’ in self reports of sexual satisfaction? Research and policy implications. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 8, 304–320. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-011-0067-9

Milhausen, R. R., & Herold, E. S. (2002). Reconceptualizing the sexual double standard. Journal of Psychology & Human Sexuality, 13, 63–83. https://doi.org/10.1300/J056v13n02_05

Moyano, N., Sánchez-Fuentes, M. M., Parra-Barrera, S. M., & Granados de Haro, R. (2022). Only ‘yes’ means ‘yes’: Negotiation of sex and its link with sexual violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 38, 2759–2777. https://doi.org/10.1177/08862605221102483

Moyano, N., Vallejo-Medina, P., & Sierra, J. C. (2016). Sexual desire inventory: Two or three dimensions? The Journal of Sex Research, 54, 105–116. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2015.1109581

Muehlenhard, C. L., & Quackenbush, D. M. (2011). The sexual double standard scale. In T. D. Fisher, C. M. Davis, W. L. Yarber, & S. L. Davis (Eds.), Handbook of sexuality-related measures (pp. 199–200). Taylor & Francis.

Parish, S. J., & Hahn, S. R. (2016). Hypoactive sexual desire disorder: A review of epidemiology, biopsychology, diagnosis, and treatment. Sexual Medicine Reviews, 4, 103–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sxmr.2015.11.009

Parish, W. L., Luo, Y., Stolzenberg, R., Laumann, E. O., Farrer, G., & Pan, S. (2007). Sexual practices and sexual satisfaction: A population based study of Chinese urban adults. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 36, 5–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-006-9082-y

Park, Y., & MacDonald, G. (2022). Single and partnered individuals’ sexual satisfaction as a function of sexual desire and activities: Results using a sexual satisfaction scale demonstrating measurement invariance across partnership status. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 51, 547–564. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-021-02153-y

Pascoal, P. M., Narciso, I. D. S. B., & Pereira, N. M. (2014). What is sexual satisfaction? Thematic analysis of lay people’s definitions. Journal of Sex Research, 51, 22–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2013.815149

Peixoto, M. M. (2019). Sexual satisfaction, solitary, and dyadic sexual desire in men according to sexual orientation. Journal of Homosexuality, 66, 769–779. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2018.1484231

Peixoto, M. M. (2022). Problematic sexual desire discrepancy in heterosexuals, gay men and lesbian women: Differences in sexual satisfaction and dyadic adjustment. Psychology & Sexuality, 13, 1231–1241. https://doi.org/10.1080/19419899.2021.1999313

Regnerus, M., Price, J., & Gordon, D. (2017). Masturbation and partnered sex: Substitutes or complements? Archives of Sexual Behavior, 46, 2111–2121. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-017-0975-8

Rollero, C., Moyano, N., & Roccato, M. (2023). The role of sexual consent and past non-consensual sexual experiences on rape supportive attitudes in a heterosexual community sample. Sexuality & Culture, 27, 1352–1368. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-023-10066-2

Sagebin, G., & Mara, T. (2013). Sexual double standard: A review of the literature between 2001 and 2010. Sexuality & Culture, 17, 686–704. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-012-9163-0

Sakaluk, J. K., Todd, L. M., Milhausen, R., & Lachowsky, N. J. (2013). Dominant heterosexual sexual scripts in emerging adulthood: Conceptualization and measurement. Journal of Sex Research, 51, 516–531. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2012.745473

Sánchez-Fuentes, M. M., & Santos-Iglesias, P. (2016). Sexual satisfaction in Spanish heterosexual couples: Testing the interpersonal exchange model of sexual satisfaction. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 42, 223–242. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2015.1010675

Sánchez-Fuentes, M. M., Santos-Iglesias, P., Byers, E. S., & Sierra, J. C. (2015). Validation of the Interpersonal Exchange Model of Sexual Satisfaction Questionnaire in a Spanish sample. Journal of Sex Research, 52, 1028–1041. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2014.989307

Sánchez-Fuentes, M. M., Santos-Iglesias, P., & Sierra, J. C. (2014). A systematic review of sexual satisfaction. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 14, 67–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1697-2600(14)70038-9

Santos-Iglesias, P., Sierra, J. C., García, M., Martínez, A., Sánchez, A., & Tapia, M. I. (2009). Índice de Satisfacción Sexual (ISS): Un estudio sobre fiabilidad y validez. International Journal of Psychology and Psychological Therapy, 9, 259–273.

Savas, G., & Yol, F. (2023). Contradicting perceptions of women´s and men´sexuality: Evidence of gender double standards in Türkiye. Sexuality & Culture, 27, 1661–1678. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-023-10083-1

Sierra, J. C., & Buela-Casal, G. (2004). Evaluación y tratamiento de las disfunciones sexuales. In G. Buela-Casal & J. C. Sierra (Eds.), Manual de evaluación y tratamientos psicológicos (2nd ed., pp. 439–485). Biblioteca Nueva.

Sierra, J. C., Gómez-Carranza, J., Álvarez-Muelas, A., & Cervilla, O. (2021). Association of sexual attitudes with sexual function: General vs. specific attitudes. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18, 10390. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph181910390

Sierra, J. C., Moyano, N., Vallejo-Medina, P., & Gómez-Berrocal, C. (2018). An abridged Spanish version of sexual double standard scale: Factorial structure, reliability and validity evidence. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 18, 69–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijchp.2017.05.003

Spector, I. P., Carey, M. P., & Steinberg, L. (1996). The Sexual Desire Inventory: Development, factor structure, and evidence of reliability. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 22, 175–190. https://doi.org/10.1080/00926239608414655

Tiefer, L. (2001). A new view of women´s sexual problems: Why new? Why now? Journal of Sex Research, 38, 89–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224490109552075

Ubillos-Landa, S., Goiburu-Moreno, E., Puente-Martínes, A., & Pizzaro-Ruíz, J. (2021). Influence in sex education programs: An empirical study. Revista de Psicodidáctica, 26, 123–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psicod.2021.01.001

Vílchez-Jaén, C., Álvarez-Muelas, A., & Sierra, J. C. (2022). Analysis of sexual victimization/aggression through typologies of adherence to sexual double standard in general population. Revista Iberoamericana de Psicología y Salud, 13, 28–40. https://doi.org/10.23923/j.rips.2022.01.052

Vowels, L. M., Vowels, M. J., & Mark, K. P. (2022). Identifying the strongest self-report predictors of sexual satisfaction using machine learning. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 39, 1191–1212. https://doi.org/10.1177/02654075211047004

World Association for Sexual Health. (2014). WAS declaration on sexual rights 2014. https://worldsexualhealth.net/was-declaration-of-sexual-rights-2014/

World Health Organization. (2010). Measuring sexual health: Conceptual and practical considerations and related indicators. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-RHR-10.12

World Health Organization. (2018). La salud sexual y su relación con la salud reproductiva: Un enfoque operativo. Author. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/274656/9789243512884-spa.pdf?sequence=1

Funding

Funding for open access publishing: Universidad de Granada/CBUA. This research was funded by Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades (Grant No. RTI2018-093317-B-I00), Grants for University Professor Training (Grant No. FPU18/03102). Funding for open access charge: Universidad de Granada/CBUA.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, JCS; methodology, OC, AÁ-M, and JCS; formal analysis, OC, AÁ-M, LJF, and JCS; investigation, OC, AÁ-M, LJF, and JCS; writing—original draft preparation, OC, AÁ-M, LJF, and JCS; writing—review and editing, OC, AÁ-M, and JCS; and funding acquisition, JCS. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Authors have no financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethics approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by Ethics Committee on Human Research of the University of Granada (n. 682/CEIH/2018).

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cervilla, O., Álvarez-Muelas, A., Jimeno Fernández, L. et al. Relation Between Desire and Sexual Satisfaction in Different Typologies of Adherence to the Sexual Double Standard. Sexuality & Culture (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-024-10196-1

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-024-10196-1