Abstract

While the provision of peer feedback has been widely recommended to enhance learning, many students are inexperienced in this area and would benefit from guidance. This study therefore examines the impact of instructions and examples on the quality of feedback provided by students on peer-developed learning resources produced via an online system, RiPPLE. A randomised controlled experiment with 195 students was conducted to investigate the efficacy of the approach. While the treatment group had access to instructions and examples to support their provision of feedback, the control group had no such assistance. Students’ feedback comments were coded using an adaptation of the S.P.A.R.K. (Specific, Prescriptive, Actionable, Referenced, Kind) model. The results indicate that the instructional guide and examples led to students writing more comprehensive comments. The intervention notably enhanced the presence of feedback traits matching the S.P.A.R.K. model and increased instances where multiple traits of quality were observed in a single comment. However, despite the guide’s impact, the students’ ability to provide actionable feedback was limited. These findings demonstrate the potential of develo** and integrating structured guidance and examples into online peer feedback platforms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Students providing feedback on their peers’ work has been recognised as a valuable part of the learning process (Hattie & Timperley, 2007; Nicol, 2012). Peer feedback, as it is commonly called, is the review of peers’ performances using either scores or written comments in line with relevant criteria (Falchikov & Goldfinch, 2000; Hattie & Timperley, 2007). It requires students to conceptualise constructive criticism of the work of others thereby encouraging thoughtful communication of an appraisal of peers’ work (Ballantyne et al., 2002; Jolly & Boud, 2013; McConlogue, 2015; Sluijsmans & Strijbos, 2010). The peer feedback process exposes student reviewers to new knowledge, introduces them to work of diverse quality, fosters critical thinking and evaluative judgement abilities (Carless et al., 2011; Nicol et al., 2014; Sadler, 2010; Tai et al., 2018). Thus, peer feedback both engages student-reviewers in higher-order learning activities and supports student-creators with individualised critiques from different perspectives (Cho & MacArthur, 2011; Kulkarni et al., 2015; Patchan & Schunn, 2015).

Despite the large body of literature advocating for student engagement in the feedback process, concerns have been expressed about its potential negative consequences. For example, educators typically perceive students as lacking the requisite expertise and knowledge to accurately evaluate their peers’ work and hold that their own feedback is of better quality (Hovardas et al., 2014; Patchan & Schunn, 2015). They believe that students’ feedback falls short of the essential standards of quality, reliability and effectiveness (Carless, 2009; Patchan et al., 2018; Sridharan et al., 2019; Watson et al., 2017; Winstone & Carless, 2019). Moreover, if peers provide inaccurate feedback, it may misguide the recipients, hinder their learning, and strain relationships between students. Even when feedback is accurate, students may display reduced trust in peer-assessors’ judgement, demotivating them from amending their work (Carless, 2009; Molloy & Boud, 2012; Shnayder et al., 2016; Shute, 2008; Yeager et al., 2014).

Training is considered an effective way to improve student feedback quality and various forms of training have been implemented in different learning contexts (see discussion below). However, empirical evidence to validate this belief is lacking, resulting in limited understanding of the actual influence of training. Hence, this study investigated the impact of a guide on peer feedback quality, in a context where students were producing learning resources for an online repository. This guide provided instructions and examples for producing constructive and effective feedback (see methodology section, Fig. 4). A randomised controlled trial (RCT) in which the guide was presented to half of the students was conducted to examine its impact. A mixed-method strategy was employed to assess the influence of the guide on three key dimensions: the length of the feedback comments, the appearance of desirable feedback traits (as defined by the S.P.A.R.K. model by the adjectives specific, prescriptive, actionable, referenced and kind), and the concurrent appearance of multiple traits within a single comment.

Related studies

Peer feedback and training

Training has been used in an attempt to equip students with the competence and expertise to offer good quality feedback and to build trust in both their own abilities and those of their peers (Allen & Mills, 2016; Chang, 2016; Liou & Peng, 2009; Min, 2005, 2006; Nicol et al., 2014; Top**, 2009; Van Zundert, et al., 2010; Winstone & Carless, 2019; **ao & Lucking, 2008). Common training strategies are the use of tailored examples, rubrics, checklists, guides, simple grading sheets, instructional videos, teacher modelling, in-class demonstrations and staff-student conferences outside class (Allen & Mills, 2016; Hsu & Wang, 2022; Rahimi, 2013; Wang, 2014; Zhu & Mitchell, 2012). These approaches may be used alone or in combination.

Despite the claimed relevance of these forms of training, few studies examine their effects. One exception is that by Liou and Peng (2009), investigating the effects of a guide on written peer reviews. Comparisons between reviews by trained and untrained authors showed that after receiving training students made more revision-oriented comments and were also successful in revising their own writing. A study by Min (2005) examined the impact of a feedback guide on the quality and quantity of students’ comments. The findings indicated a notable increase in the number of comments following the training. Furthermore, the students demonstrated an enhanced ability to generate more pertinent global comments (relating to content and organisation). In a recent review of nine previous studies, Hsu and Wang (2022) focussed on the training effects of asynchronous computer-mediated feedback with regards to quality of peer feedback, the adoption rate and quality of student revision in L2 writing revision. The papers reviewed showed that the training type deployed led to an improvement in feedback quality. Specifically, most studies found an increased emphasis on global-oriented comments, particularly suggestions for improvement.

Some studies have also combined approaches such as the use of tips, self-monitoring and regulation strategies and student–teacher conference to enhance feedback quality. For example, Rahimi (2013) combined training via a guide and student–teacher conferencing to support the review of different types of paragraphs and provision of effective feedback on them. The findings showed that this approach significantly improved student feedback quality, shifting attention to writing global comments (focus on content and organization). Darvishi et al. (2022) also used multiple methods of training—the provision of tips with negative and positive examples, self-monitoring and AI assistance—to enhance students’ feedback quality. The results indicated that these strategies encouraged longer feedback that the researchers perceived as useful to peers.

The limited existing research does therefore suggest the benefits of training, but across a restricted range of contexts. In addition, these training methods can be demanding in terms of time and effort for both students and staff, posing further challenges and cost concerns for teachers, especially with larger groups of students. Our investigation looks at the largely unstudied learner-sourcing context, where students were producing and moderating learning resources for an online repository, using RiPPLE, a teaching and research platform. The study explores the impact of a guide with instructions and examples for producing constructive, effective feedback. The training option adopted, here administered to 95 students, can easily be applied to much larger cohorts with no additional outlay of time or resources.

Criteria for good quality peer feedback

Various suggestions have been made as to how to judge the quality of peer feedback. Content analysis research investigating features of desirable feedback (e.g. Cavalcanti et al., 2020; Zhu & Carless, 2018) suggests that good feedback includes comments of various kinds: it follows that better feedback is therefore typically longer. As a result, length has been widely adopted as a quick quantitative indicator of quality. One study which directly reports a significant positive relationship between comment length and perceived feedback quality is that of Zong et al. (2021). However, despite the usefulness of length as a metric, debates still arise as to whether it is a reliable indicator of quality.

Qualitative approaches are also used to investigate peer feedback (Hattie & Timperley, 2007; Nicol & Macfarlane-Dick, 2006). For instance, judgements as to whether feedback is detailed or simple; praises or criticizes; identifies problems or/and gives solutions; is general or specific, descriptive or explanatory have been used as indicators of feedback quality (Cho & MacArthur, 2011; Sluijsmans & Strijbos, 2010; Wu & Schunn, 2020). Other scholars have cited factors such as the incorporation of positive and negative judgements along with constructive suggestions for revision as qualitative criteria for the analysis or coding of students’ feedback (Hovardas et al., 2014; Prins et al., 2006; Tsai & Liang, 2009).

This study combines quantitative and qualitative metrics to determine the impact of an instructional guide on comments provided by peer reviewers. In addition to measuring comment length, it adapts an existing framework for traits of high-quality feedback, as outlined below.

Research questions

The questions below guided the study:

What is the impact of the instructional guide and examples on:

-

1.

The length of comments?

-

2.

The presence of traits of good quality feedback in comments?

-

3.

The co-occurrence of traits within the same piece of feedback?

It was hypothesized that the training, in the form of the instructional guide and examples, would encourage students to provide longer and more detailed comments (H1). Additionally, there would be a significant difference between feedback from the trained and untrained groups with respect to the presence of the traits of good quality feedback (H2) and the extent to which the traits of quality feedback co-occurred within the same piece of feedback (H3).

Methodology

Research tool—representation in peer personalised learning environment (RiPPLE)

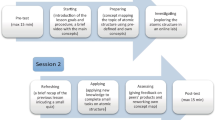

RiPPLE, a tool developed at the University of Queensland, was the main instrument used for the study. It aims to enhance students’ creativity and evaluative skills as experts-in-training by involving them in the creation and evaluation of a bank of high-quality learning resources which can be used in a given course (Khosravi et al., 2019, 2020). To this end, the platform provides students with templates through which they can create a range of learning materials, namely multiple-choice questions, multi-answer questions, worked examples and the open-ended resource called “notes”. Figure 1 shows the interface used for creating a “note” learning resource as used in this study.

Since the resources students initially create could be incorrect or ineffective, a standard practice is for them to be evaluated before release to the final resource bank. To reduce dependency on instructors, and to promote learning, RiPPLE further relies on students to evaluate the quality of learning resources which they and their peers have created, by calling on their competencies associated with evaluative judgement, “the ability to make decisions about the quality of one’s own work and that of others” (Tai et al., 2018; see also Gyamfi et al., 2021a). When students log on to the site as moderators, they are presented with resources to evaluate and on the basis of the scores of multiple peers, a resource is either returned to the original author for improvement or released into the resource bank for general use. Figure 2 shows a sample interface with multiple moderations of the same resource and the final decision. This peer-moderation process in RiPPLE may be supported by rubrics (of varying degrees of complexity e.g. grading scheme/open ended questions), and provision of exemplars. RiPPLE further provides generic training guides that are efficiently applicable in different course contexts. The guides can also be customized to suit the demands of specific courses.

RiPPLE is also a research tool which allows experimentation and data gathering, supporting sound, large-scale empirical educational research designs such as RCTs and quasi-observational experiments by collecting data through reliable, sustainable, and ethical means (Abdi et al., 2021; Darvishi et al., 2022; Khosravi et al., 2019, 2020). The impact of RiPPLE on learning gains has been analysed and reported in two peer-reviewed studies (Gyamfi et al., 2021b; McDonald et al., 2021).

Context and participants

One hundred and ninety-five (195) postgraduate students enrolled in a 13-week applied linguistics course participated in this study. The course provided students with an overview of second language development and use in formal and naturalistic settings. The students were asked to produce “notes” in the form of weekly reflections in response to questions posed by the lecturer to support learning and revision. The resources had to meet a masters-level standard of writing and criticality and be at least 150 words in length. Students produced at least 10 of these “notes” during the semester (one resource per week over ten weeks).

Once created, the learning resources were randomly allocated for peer review. Each student carried out at least three evaluations per week over ten weeks, thus producing a minimum of 30 evaluations over the semester. The students used a rubric to score the quality of their peers’ work out of five and rated their confidence in their scores. Written comments justified their ratings and provided feedback for the improvement of resources.

A resource had to be evaluated at least 3 times with an average result of at least 3.5/5 before it passed moderation and was made available for use by peers. This use of multiple evaluations ensured that a decision on the quality of a resource was not based on a single individual’s opinion.

Intervention

In line with research on improving peer feedback quality, the RiPPLE team designed a set of tips for students to consider while writing their reviews (Henderson et al., 2019; Nelson & Schunn, 2009; Nicol & Macfarlane-Dick, 2006; Zong et al., 2021). The aim was that students both write and receive better feedback. The guide, housed on RiPPLE, popped up the first time students began to provide feedback. Subsequently, it was accessible any time and as often as needed. This reinforced the use of the guidelines and helped students check whether they had incorporated them in their feedback. The following traits were presented as desirable: 1. alignment with the rubric used for grading resource quality (see the resource feedback section in Fig. 3.), 2. detail and specificity, 3. inclusion of suggestions for improvement and 4. use of constructive language. An outline of all the tips was displayed on the first slide (Fig. 4.). The subsequent slides gave more detailed explanations and, for each of the four tips, sample comments demonstrated how feedback should be constructed highlighting, for example, the importance of being kind, being specific, offering suggestions for improvement, and highlighting areas of strength and weakness.

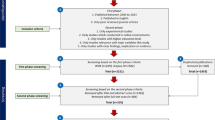

Experimental design

The study employed an RCT design, which is widely recognized as a highly rigorous and reliable approach to assessing the effectiveness of interventions in educational research (Torgerson & Torgerson, 2001). Through random assignment of students to treatment and control groups, any observed disparities in outcomes can be directly linked to the intervention rather than other factors.

In this study, the RCT was designed to explore the impact of the guide described above on the feedback provided by students. The students were randomly divided into a trained group, which had access to the guide, and an untrained group which did not.

Data collection

Data were collected from 195 consenting students who participated in resource creation and moderation, an untrained control group (n = 100) and a trained experimental group (n = 95). The dataset collected from both groups during the 13-week period of the study comprised students’ scores and comments justifying their scoring and providing feedback. The students completed a total of 7231 moderations, more than the expected 5850 moderations (195 students × 10 weeks × 3 weekly reviews). This means that some students evaluated more than the required three learning resources each week.

Data analysis

Of the 7231 moderations, 3778 and 3452 were completed by the untrained group and the trained group respectively. These were used to answer RQ1 (on length).

For the qualitative analysis, comments with 5 or less words were excluded, leaving a total of 5907 comments: 3054 and 2852 comments written by the untrained and the trained groups respectively. Of these, 305 and 285 comments, comprising every tenth comment based on time of creation, were then sampled from each group for content analysis. Table 1 provides a quantitative summary of the dataset.

The following metrics were used to determine the impact of the guide on the quality of feedback:

Length of comments

We undertook a student level analysis of the average word length of comments provided per student across multiple moderations. The average length and standard deviation were then computed for each group. The Mann Whitney U test and Cohen’s d were used to perform the statistical analysis of comment length and estimate the effect size of the feedback guide respectively.

Presence of S.P.A.R.K. traits of optimal feedback in comments

Comments were coded for the traits of the S.P.A.R.K. model (Specific, Prescriptive, Actionable, Referenced, Kind) (see below). We calculated the percentage of the sampled comments from each group that included the S.P.A.R.K. traits, and also how the traits were represented in the dataset, relative to each other.

Co-occurrence of S.P.A.R.K. traits in the same piece of feedback

A further analysis measured the co-occurrence of multiple traits in the same comment. This indicated the overall quality of feedback, that is, the more the co-occurrences the better the feedback.

Framework to determine the quality of feedback

The comments were coded in NVIVO using criteria derived from Gardner’s (2019) S.P.A.R.K. model. The use of these independent criteria rather than those of the feedback guide was motivated by the need to avoid unduly exaggerating any difference between the groups. That is, it was deemed inappropriate to assess the untrained group based on specific criteria to which they did not have access. The mnemonic S.P.A.R.K. presents five recommended traits of feedback: it should be Specific, Prescriptive, Actionable, Referenced, Kind. However, since the five points were designed as easily memorized suggestions rather than as a coding scheme, to suit the purpose of the study they were adapted to enable the analysis of peer feedback quality. For instance, the original definitions of the criteria “prescriptive” and “actionable” overlapped and were difficult to differentiate consistently. Hence, for coding purposes, the definitions were revised for a tighter and clearer distinction between the traits. In line with Braun and Clark (2006), a double coder was consulted to ensure that the adapted definitions had been sufficiently described to produce clarity, replicability and validity. 30% of the comments provided by each group were randomly selected for double coding by the lead researcher and the double coder. Cohen’s Kappa coefficient analysis was conducted to measure the degree of inter-rater agreement was excellent at 0.83 between the coders with an inter-rater agreement of 95.2% across all the codes. A final consensus was reached on the definitions after highlighting similarities, differences and unanticipated insights generated by the original codebook. Table 2 shows the coding scheme of agreed definitions between coders along with sample comments.

Findings

Impact of the training guide on length of comments

A student level analysis of the length of comments was undertaken to determine how the guide impacted students’ apparent effort and willingness to provide feedback to peers. To do this the average length of comments provided by each student across multiple moderations was calculated. Figure 5, below, shows that on average students from the trained group provided longer comments (µ = 26.23, Mdn = 23, σ = 20.05) than the untrained group (µ = 21.47, Mdn = 20, σ = 18.14) across multiple moderations. As shown in Table 3, this difference was statistically significant, U = 42,621 p < 0.001, however the effect size was small, d = 0.24. Whether longer comments indicated the incorporation of more suggestions from the feedback guide remains to be seen in the subsequent analysis.

Presence of S.P.A.R.K. traits in feedback

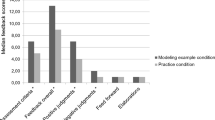

Figure 6 shows the percentages of comments that were coded as including/omitting the S.P.A.R.K.-derived traits. A higher percentage of comments from the trained group, 71.20%, displayed at least one S.P.A.R.K. trait compared to those from the untrained group (59.10%).

Further analysis determined the presence of each of the S.P.A.R.K. traits in the feedback from each group. This revealed that each individual S.P.A.R.K. trait could be identified in a higher percentage of comments from the trained group compared to the untrained group (Fig. 7). Although there was a difference in percentages, the relative presence of traits was similar in the two groups: the code “specific” was applied to the highest percentage of comments for both the trained (36.1%) and untrained group (23.3%) while the code “actionable” matched the lowest percentage of comments. Overall, the chi-square goodness of fit test revealed a statistically significant difference between the groups in the extent to which each S.P.A.R.K. trait was displayed, p < 0.05.

Co-occurrence of S.P.A.R.K. traits within the same piece of feedback

The findings show that both groups could produce comments which displayed more than one S.P.A.R.K. trait. However, the trained group provided a higher percentage of comments (87%) with multiple codes compared to the untrained group (55.72%): see Fig. 8 where the Y axis indicates the percentage of comments while the X axis refers to the number of traits that occurred in the same piece of feedback. However, the low percentage of comments that displayed all five traits, 16.50% and 6.42% for the trained and untrained group respectively, means that the peer assessors had difficulties in providing comprehensive feedback. The guide did, however, allow the trained group to be more successful in producing high quality feedback.

An additional analysis was conducted to determine whether the difference between the two groups with respect to the co-occurrence of the S.P.A.R.K. criteria was significant. The chi square statistic showed a significant difference (p < 0.05), except for feedback that had two codes, p = 0.937. This means that the guidance provided to students made a difference in the quality of their feedback.

Discussion

Impact on length of comments

The findings confirmed our first hypothesis that the feedback guide would enable students to provide lengthier comments. As established in the analysis above, the comments provided by the trained group were longer because they contained more features of quality compared to those provided by the untrained group. This shows the enabling role of the guide in assisting students to provide more detailed feedback. The finding aligns with previous research indicating that trained students provide detailed feedback which researchers perceive as more likely to be valuable to receivers (Cho & MacArthur, 2011; Deiglmayr, 2018; Lundstrom & Baker, 2009; Wichmann et al., 2018). Hence, while it may not necessarily be the case that length always aligns with quality, in this case a higher word count was an indicator of better feedback.

Presence of the S.P.A.R.K. traits in the feedback provided

The results showed a significant difference in the presence of S.P.A.R.K. traits in the comments provided by the two groups. That is, the guide encouraged the trained group to provide a greater percentage of comments containing traits of high-quality feedback. Despite this difference, there were similarities in the extent to which specific traits appeared in the feedback from the two groups. “Specific” was the most present trait in both sets of feedback while "actionable” was the least. That “specific” was applied to the highest percentage of comments suggests both that students are commonly exposed to specificity in feedback and could draw on models, even without explicit training, and that it was relatively easy for them to provide comments of this kind.

Another instance of the shared understanding of the nature of good quality feedback pertains to comments coded as “prescriptive”, (such as recommending the inclusion of content from different weeks, practical examples, or references to literature). Both groups produced such feedback, although it was not specifically recommended by the guide.

“Actionable”, the least-present trait in comments from both groups was applied to comments which told the author exactly what to do to amend a resource, rather than simply making a recommendation. Students may have perceived that such direct assertion of authority was not commensurate with their standing as peers, that they were neither positioned nor equipped to offer such advice, which would be the purview of experts (Hyland, 2000; Patton, 2012). It is noteworthy, however, that the trained group did offer more “actionable” comments (14%) than the untrained group (9.5%). This therefore suggests that the guide encouraged students to perceive themselves as potential contributors of such feedback, and that some of them accepted the invitation to do so: the instructions presented the notion that offering “actionable” recommendations is not an exclusive domain of experts but also within the capacity of students. At the same time, the low percentages for actionable feedback may be reassuring to instructors who fear that peer review is a source of incorrect guidance: it seems that students largely held back from explicit direction involving domain knowledge.

Concerning comments that were coded as “referenced”, directly referencing the task criteria, requirements, or target skills, analysis of the content reveals an interesting contrast between the two groups. The points of reference for the untrained group were mainly the rubric for scoring resource quality, task criteria and course requirements. Some members of the trained group on the other hand, apparently acted on the explanation of Tip 1 to provide comments on how a resource did or did not encourage the targeted skill of higher-order thinking.

In relation to the criterion “kind,” the guide explained the importance of using constructive language to provide feedback in a professional and respectful tone. The higher percentage of comments from the trained group suggests that the tips enabled students to better understand how their feedback could impact their peers’ feelings.

In sum, while there were some similarities in peer feedback quality, the guide made a difference by enabling the provision of a higher percentage of comments containing traits of effective feedback.

Co-occurrence of S.P.A.R.K. criteria within the same comment

Comments from the trained group also had a higher co-occurrence of S.P.A.R.K. traits in the same piece of feedback (Fig. 8). This tended to confirm our hypothesis that the guide would support students to provide comments including multiple characteristics of high-quality feedback (H3). The statistically significant difference in the percentage of multiple codes applied to the comments means that the guide drew students’ attention to the fact that effective feedback incorporates more than one trait of quality. Nonetheless, providing good quality, comprehensive feedback is still a challenge for students, as evidenced by the low percentage of comments that displayed all five traits, even from the trained group (16.50% and 6.42% for the trained and untrained group respectively). Therefore, although the guide supported students to refine and apply their understanding of what constitutes high quality feedback, that is, to develop their evaluative judgement (Tai et al., 2018) in relation to feedback, there is still much room for improvement.

Conclusion

Overall, the study revealed that giving guidance to students can make a difference in the quality of feedback they provide. The training guide, with its concise tips and examples which were easily accessible while students were writing their feedback, proved useful by encouraging them to write longer and more detailed comments that incorporated multiple traits of high-quality feedback. The study also revealed areas of students’ strengths and limitations in their ability to provide effective feedback. In particular, the analysis led to the discovery that while it is relatively easy to provide “specific” feedback, the offering of “actionable” feedback was a common difficulty on the part of peer assessors whether trained or untrained. As noted above, while the trained group consistently did “better”, there was still room for improvement. Nonetheless, the results are encouraging when we remember that this intervention took a very light touch approach. The training was provided to 95 students with no demands on instructors or class time, and students were in fact free to ignore it. If feedback quality were an important course outcome, a greater impact could potentially be achieved with some in-class discussion of the tips or other requirements that students read and reflect on them. What further distinguishes this study from others and represents a contribution to literature, is its emphasis on cultivating students’ evaluative judgement regarding feedback quality. The guide, with instructions and examples, offered students a chance to enhance their evaluative judgement in relation to feedback quality by comprehending, applying, and discerning the characteristics of high-quality feedback.

Limitations, recommendations, and future work

A major limitation of this research relates to the duration of the study. While the short-term intervention produced some improvement, future studies could examine the effect of long-term training over time (beyond a semester) on peer feedback quality. Secondly, we have limited understanding of the extent to which the students read the guide or consulted it after it had popped up the first time. In addition, given the challenges of designing sustainable training interventions, it would be valuable to explore student perceptions of the guide, the advice it offered and the format in which it was presented. While this study assumed certain characteristics of high-quality feedback identified in preceding research, future work could explore peers’ views of the usefulness of the feedback they received. Furthermore, the study did not take into consideration demographics such as language background, past feedback experiences and how they potentially affected the quality of student feedback, nor did it compare these postgraduate students with undergraduate students. Future experimental designs could take this into account to enable a more nuanced understanding of the impact of training on the quality of peer feedback provided by different populations.

References

Abdi, S., Khosravi, H., Sadiq, S., & Demartini, G. (2021). Evaluating the quality of learning resources: A learnersourcing approach. IEEE Transactions on Learning Technologies, 14(1), 81–92. https://doi.org/10.1109/TLT.2021.3058644

Allen, D., & Mills, A. (2016). The impact of second language proficiency in dyadic peer feedback. Language Teaching Research, 20(4), 498–513.

Ballantyne, R., Hughes, K., & Mylonas, A. (2002). Develo** procedures for implementing peer assessment in large classes using an action research process. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 27(5), 427–441.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101.

Carless, D. (2009). Trust, distrust and their impact on assessment reform. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 34(1), 79–89.

Carless, D., Salter, D., Yang, M., & Lam, J. (2011). Develo** sustainable feedback practices. Studies in Higher Education, 36(4), 395–407.

Cavalcanti, A. P., Diego, A., Mello, R. F., Mangaroska, K., Nascimento, A., Freitas, F., & Gašević, D. (2020). How good is my feedback? A content analysis of written feedback. In Proceedings of the Tenth International Conference on Learning Analytics & Knowledge (pp. 428–437).

Chang, C. Y. H. (2016). Two decades of research in L2 peer review. Journal of Writing Research, 8(1), 81–117.

Cho, K., & MacArthur, C. (2011). Learning by reviewing. Journal of Educational Psychology, 103(1), 73–84.

Darvishi, A., Khosravi, H., Abdi, S., Sadiq, S., & Gašević, D. (2022). Incorporating training, self-monitoring and AI-assistance to improve peer feedback quality. In Proceedings of the Ninth ACM Conference on Learning @ Scale June 2022 (pp. 35–47) https://doi.org/10.1145/3491140.3528265

Deiglmayr, A. (2018). Instructional scaffolds for learning from formative peer assessment: Effects of core task, peer feedback, and dialogue. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 33(1), 185–198.

Falchikov, N., & Goldfinch, J. (2000). Student peer assessment in higher education: A meta-analysis comparing peer and teacher marks. Review of Educational Research, 70(3), 287–322.

Gardner, M. (2019). Teaching students to give peer feedback. Retrieved from https://www.edutopia.org/article/teaching-students-give-peer-feedback

Gyamfi, G., Hanna, B. E., & Khosravi, H. (2021a). The effects of rubrics on evaluative judgement: A randomised controlled experiment. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 47(1), 126–143.

Gyamfi, G., Hanna, B., & Khosravi, H. (2021b). Supporting peer evaluation of student-generated content: A study of three approaches. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 47(7), 1129–1147.

Hattie, J., & Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), 81–112.

Henderson, M., Phillips, M., Ryan, T., Boud, D., Dawson, P., Molloy, E., & Mahoney, P. (2019). Conditions that enable effective feedback. Higher Education Research & Development, 38(7), 1401–1416.

Hovardas, T., Tsivitanidou, O. E., & Zacharia, Z. C. (2014). Peer versus expert feedback: An investigation of the quality of peer feedback among secondary school students. Computers & Education, 71, 133–152.

Hsu, K. C., & Wang, Y. (2022). A review on the training effects and learners’ perceptions towards asynchronous computer-mediated peer feedback for L2 writing revision. International workshop on learning technology for education challenges (pp. 139–152). Springer.

Hyland, F. (2000). ESL writers and feedback: Giving more autonomy to students. Language Teaching Research, 4(1), 33–54.

Jolly, B., & Boud, D. (2013). Written feedback: What is it good for and how can we do it well? In D. Boud & E. Molloy (Eds.), Feedback in higher and professional education: Understanding it and doing it well (pp. 104–124). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203074336

Khosravi, H., Kitto, K., & Williams, J. J. (2019). RiPPLE: A crowdsourced adaptive platform for recommendation of learning activities. Journal of Learning Analytics, 6(3), 91–105.

Khosravi, H., Sadiq, S., & Gasevic, D. (2020). Development and adoption of an adaptive learning system: Reflections and lessons learned. In Proceedings of the 2020 ACM SIGCSE Technical Symposium on Computer Science, Education (pp. 58–64).

Kulkarni, C. E., Bernstein, M. S., & Klemmer, S. R. (2015). PeerStudio: Rapid peer feedback emphasizes revision and improves performance. In Proceedings of the second (2015) ACM Conference on Learning@ scale (pp. 75–84).

Liou, H. C., & Peng, Z. Y. (2009). Training effects on computer-mediated peer review. System, 37(3), 514–525.

Lundstrom, K., & Baker, W. (2009). To give is better than to receive: The benefits of peer review to the reviewer’s own writing. Journal of Second Language Writing, 18(1), 30–43.

McConlogue, T. (2015). Making judgements: Investigating the process of composing and receiving peer feedback. Studies in Higher Education, 40(9), 1495–1506.

McDonald, A., McGowan, H., Dollinger, M., Naylor, R., & Khosravi, H. (2021). Repositioning students as co-creators of curriculum for online learning resources. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 37(6), 102–118. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.6735

Min, H. T. (2005). Training students to become successful peer reviewers. System, 33(2), 293–308.

Min, H. T. (2006). The effects of trained peer review on EFL students’ revision types and writing quality. Journal of Second Language Writing, 15, 118–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2006.01.003

Molloy, E., & Boud, D. (2012). Changing conceptions of feedback. In D. Boud & E. Molloy (Eds.), Feedback in higher and professional education (pp. 21–43). Routledge.

Nelson, M. M., & Schunn, C. D. (2009). The nature of feedback: How different types of peer feedback affect writing performance. Instructional Science, 37(4), 375–401.

Nicol, D. (2012). Resituating feedback from the reactive to the proactive. In D. Boud & E. Molloy (Eds.), Feedback in higher and professional education (pp. 44–59). Cham: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203074336

Nicol, D., Thomson, A., & Breslin, C. (2014). Rethinking feedback practices in higher education: A peer review perspective. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 39(1), 102–122.

Nicol, D. J., & Macfarlane-Dick, D. (2006). Formative assessment and self-regulated learning: A model and seven principles of good feedback practice. Studies in Higher Education, 31(2), 199–218.

Patchan, M. M., & Schunn, C. D. (2015). Understanding the benefits of providing peer feedback: How students respond to peers’ texts of varying quality. Instructional Science, 43(5), 591–614.

Patchan, M. M., Schunn, C. D., & Clark, R. J. (2018). Accountability in peer assessment: Examining the effects of reviewing grades on peer ratings and peer feedback. Studies in Higher Education, 43(12), 2263–2278.

Patton, C. (2012). ‘Some kind of weird, evil experiment’: Student perceptions of peer assessment. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 37(6), 719–731.

Prins, F. J., Sluijsmans, D., & Kirschner, P. A. (2006). Feedback for general practitioners in training: Quality, styles, and preferences. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 11(3), 289–303.

Rahimi, M. (2013). Is training student reviewers worth its while? A study of how training influences the quality of students’ feedback and writing. Language Teaching Research, 17(1), 67–89.

Sadler, D. R. (2010). Beyond feedback: Develo** student capability in complex appraisal. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 35(5), 535–550.

Shnayder, V., Agarwal, A., Frongillo, R., & Parkes, D. C. (2016). Informed truthfulness in multi-task peer prediction. In Proceedings of the 2016 ACM Conference on Economics and Computation (pp. 179–196).

Shute, V. J. (2008). Focus on formative feedback. Review of Educational Research, 78(1), 153–189.

Sluijsmans, D. M., & Strijbos, J. W. (2010). Flexible peer assessment formats to acknowledge individual contributions during (web-based) collaborative learning. In B. Ertl (Ed.), E-collaborative knowledge construction: Learning from computer-supported and virtual environments (pp. 139–161). Information Science Reference/IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-61520-729-9.ch008

Sridharan, B., Tai, J., & Boud, D. (2019). Does the use of summative peer assessment in collaborative group work inhibit good judgement? Higher Education, 77(5), 853–870.

Tai, J., Ajjawi, R., Boud, D., Dawson, P., & Panadero, E. (2018). Develo** evaluative judgement: Enabling students to make decisions about the quality of work. Higher Education, 76(3), 467–481.

Top**, K. J. (2009). Peer assessment. Theory into Practice, 48(1), 20–27.

Torgerson, C. J., & Torgerson, D. J. (2001). The need for randomised controlled trials in educational research. British Journal of Educational Studies, 49(3), 316–328.

Tsai, C. C., & Liang, J. C. (2009). The development of science activities via on-line peer assessment: The role of scientific epistemological views. Instructional Science, 37(3), 293–310.

Van Zundert, M., Sluijsmans, D., & Van Merriënboer, J. (2010). Effective peer assessment processes: Research findings and future directions. Learning and Instruction, 20(4), 270–279.

Wang, W. (2014). Students’ perceptions of rubric-referenced peer feedback on EFL writing: A longitudinal inquiry. Assessing Writing, 19, 80–96.

Watson, F. F., Castano Bishop, M., & Ferdinand-James, D. (2017). Instructional strategies to help online students learn: Feedback from online students. TechTrends, 61(5), 420–427.

Wichmann, A., Funk, A., & Rummel, N. (2018). Leveraging the potential of peer feedback in an academic writing activity through sense-making support. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 33(1), 165–184.

Winstone, N., & Carless, D. (2019). Designing effective feedback processes in higher education: A learning-focused approach (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351115940

Wu, Y., & Schunn, C. D. (2020). From feedback to revisions: Effects of feedback features and perceptions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 60, 101826.

**ao, Y., & Lucking, R. (2008). The impact of two types of peer assessment on students’ performance and satisfaction within a Wiki environment. The Internet and Higher Education, 11(3–4), 186–193.

Yeager, D. S., Purdie-Vaughns, V., Garcia, J., Apfel, N., Brzustoski, P., Master, A., & Cohen, G. L. (2014). Breaking the cycle of mistrust: Wise interventions to provide critical feedback across the racial divide. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 143(2), 804.

Zhu, Q., & Carless, D. (2018). Dialogue within peer feedback processes: Clarification and negotiation of meaning. Higher Education Research & Development, 37(4), 883–897.

Zhu, W., & Mitchell, D. A. (2012). Participation in peer response as activity: An examination of peer response stances from an activity theory perspective. TESOL Quarterly, 46(2), 362–386.

Zong, Z., Schunn, C. D., & Wang, Y. (2021). Learning to improve the quality peer feedback through experience with peer feedback. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 46(6), 973–992.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gyamfi, G., Hanna, B.E. & Khosravi, H. Impact of an instructional guide and examples on the quality of feedback: insights from a randomised controlled study. Education Tech Research Dev 72, 1419–1437 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-024-10346-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-024-10346-0