Abstract

In China, agricultural activities are a major source of greenhouse gas emissions, ranking second only to another significant source. This presents a significant obstacle to reducing emissions and jeopardizes both the availability of food and the sustainable growth of agriculture. It is primarily the farmers who utilize cultivated land and are thus accountable for the initiation of these emissions. Farmers’ role is significant in adopting green and low-carbon (LC) agricultural production practices, and their actions are directly tied to the achievement of the dual goals of carbon reduction. Understanding their motivations for engaging in LC production and the factors that influence their willingness to do so is important for both theory and practice. In this study, data was collected from 260 questionnaires in 13 counties across five major cities in Shaanxi Province. The purpose was to identify factors that impact farmers’ motivation and willingness to engage in LC agriculture using linear regression analysis. A structural equation model was constructed to better understand the underlying mechanisms that influence farmers’ actions towards LC farming practices. The study’s findings indicate that (1) farmers’ behavior towards LC production practices is notably impacted by internal motivation based on joy and internal motivation based on responsibility (IMR); (2) IMR has the most pronounced effect on farmers’ adoption of LC production practices; (3) the internal motivation based on joy, IMR, behavior attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavior control are related to each other; and (4) the multi-group analysis of the data indicates that the impact of internal motivation based on joy and IMR on adopting sustainable farming practices may vary among different groups. It is essential to support farmers who have strong intrinsic motivation to engage in sustainable agriculture. Additionally, policymakers must promote positive attitudes towards sustainable farming to achieve the desired environmental (LC) objectives.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Climate change is a critical global issue that poses severe threats to human survival and development. Rapid urbanization and industrialization have led to increased energy consumption and subsequent carbon emissions, which contribute significantly to climate change (Ali and Yi 2022; Sikder et al. 2022). The consequences of climate change caused by carbon emissions include extreme weather events, ecological fragility, and economic losses, among others (Masson-Delmotte et al. 2021). These consequences highlight the urgent need to develop a low-carbon (LC) society that promotes the coordinated development of the environment and economy to mitigate resource crises and ecological degradation (** et al. 2020). Thus, global carbon emission reduction is a necessity.

Develo** countries are the most vulnerable to climate change, which can undermine their development prospects (UNDP 2011; Gunarathne et al. 2020) (UNDP 2011; Dube et al. 2022). Therefore, these countries must take proactive steps to mitigate the effects of climate change by reducing their carbon emissions. Therefore, develo** countries have the responsibility to adopt new and innovative methods, make use of existing experiences, and incorporate them into a comprehensive policy framework to support development plans, policies, and action plans across multiple sectors and levels (UNDP 2011; Gunarathne et al. 2020). In 2020, ** put forward the goal of “double carbon,” and the net zero commitment was the first step to achieve carbon neutrality (Hao et al. 2022; Lin et al. 2023). According to the latest data on the population of China released by the National Bureau of Statistics, there are 498.35 million rural people, accounting for 35.28% (Pei et al. 2021; Zhu 2021). Although the overall China’s rural population has shown a negative growth trend in recent years, it still occupies a large proportion and its distribution is scattered (Li 2021). As the main body of agricultural production and management, farmers are naturally the “initiators” of agricultural carbon emissions (Cui 2021; Yang 2021; Yue 2021), and they are also the important subjects involved in green and LC agricultural production. Their behavior is directly related to the realization of the double-carbon goal. According to studies, agriculture ranks as the second largest emitter of carbon emissions, after the burning of fossil fuels (Aguilera et al. 2021; Liu and Yang 2021). Capital-intensive modern agricultural development mode relies heavily on the extensive use of production factors such as energy (Khan 2021, Zhou 2021), which makes agricultural carbon emission reduction in China face enormous pressure.

Although the goal of carbon neutrality forced Chinese government to vigorously develop LC agriculture and circular agriculture, increase investment in agricultural LC technology, and promote green agricultural production, the effect was not obvious. Farmers play a crucial role in the use of agricultural land and the adoption of farming technology, making their LC production practices a significant factor in reducing carbon emissions in agriculture (Hou and Hou 2019; Zhao and Zhou 2021). Agricultural production and agricultural carbon emission reduction seem to be a pair of contradictions. When farmers are faced with the trade-off between agricultural output and agricultural carbon emission reduction, giving priority to ensuring the agricultural output level seems to be the “inevitable” choice of “rational” farmers (Lei 2021), but the reality is often complicated and changeable. With the global trend of carbon emission reduction, farmers’ awareness of the environment has been continuously improved. Farmers’ decision-making behavior in agricultural production is not only driven by economic interests (Ethel 2021; Wang 2021; Wu 2021; Deng 2022), but more farmers have the tendency of agricultural LC behavior. How to explain the motivation of farmers’ LC behavior? How does this motivation affect farmers’ willingness and behavior of LC behavior? What role does it play in changing farmers’ LC behavior intention from idea to action? The widespread adoption of LC agricultural practices, encouraging farmers to prioritize LC production methods, and guiding them towards transitioning from high-input, high-output production to LC technologies is crucial in achieving sustainable development in agriculture. Therefore, it is important to explore ways in which farmers can reduce carbon emissions during agricultural production.

Several factors and their interdependent relationships influence the LC production practices of farmers (Huang 2019; Ren 2021; Zhang 2021). Among these factors, internal motivation and external motivation are the two major drivers that encourage farmers to adopt LC production methods (Li 2020). Since the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs launched the zero growth of chemical fertilizers and pesticides in 2015, the efficiency of fertilization and drug use has gradually improved. However, by 2020, the utilization rates of chemical fertilizers and pesticides of rice, wheat and corn were only 40.2% and 40.6%, respectively (www.gov.cn). In 2021, the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs released ten technology models for carbon sequestration in agriculture and rural areas, among which four technologies involved in agricultural production are mainly methane emission reduction technology in rice fields, nitrous oxide emission reduction technology in farmland, carbon sequestration technology in conservation tillage, and carbon sequestration technology in straw returning to fields. The popularization and use of these technologies in rural areas are uneven, and farmers have mixed opinions.

Shaanxi Province strongly advocates LC agricultural economy, but there are many problems. At the beginning of 2006, Shaanxi Province was designated as one of the pilot provinces of China’s National Plan for Climate Change. At the same time, Shaanxi’s Plan for Climate Change was issued, which put forward the guiding ideology, basic principles, guiding objectives, and implementation plans for climate change and LC development. Since then, relevant policies and measures have been introduced continuously, and green economy, LC economy, and circular economy have been regarded as new development concepts. Shaanxi Province is one of the provinces that accepted the idea of LC economy earlier and actively developed LC economy (Gao 2020). With the strong advocacy and encouragement of Shaanxi provincial government, the LC economy has developed and achieved initial results. In 2010, the province’s carbon sink was about 21.23 million tons (Luo 2021). In recent years, Shaanxi has accelerated the rapid transformation from traditional agriculture to modern agriculture, and the comprehensive agricultural production capacity has obviously increased, with grain production exceeding 10 million tons year after year. However, there are still some problems, such as LC agricultural production technology bottleneck, extensive production mode, irrational structure of agricultural machinery and equipment, excessive use of pesticides and fertilizers, low acceptance of LC production mode by farmers, lack of LC awareness of farmers, and imperfect LC technology promotion system (Tang 2018; Yang 2020; Zhang 2021). Therefore, finding out the fundamental and long-term influencing factors of farmers’ LCPB, exploring how to improve the initiative of small farmers to adopt LC production and form endogenous long-term mechanism to guide agriculture to LC, high-quality and efficient development has become the focus of current research.

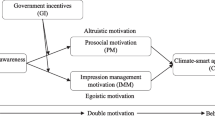

This study covers farmers’ internal and external motivation, LC cognition, behavior attitude, subjective norm, perceived behavior control, LC behavior willingness, and farmers’ LCPB. The purpose of this study is to verify the action path between the internal motivation of farmers’ LC behavior and farmers’ LC behavior and further analyze the possible “motivation crowding” between the internal motivation and external motivation of farmers’ agricultural LC behavior, as well as the relationship between the internal motivation, willingness, and LC behavior of farmers. To begin with, a review of the existing literature was conducted to establish a model outlining the mechanism through which LC behavior is influenced. Subsequently, four hypotheses were formulated. A random questionnaire survey was then conducted in rural areas of Shaanxi Province to gather data on farmers’ motivation, awareness, and LC production practices. The survey data was then used to verify the hypotheses and identify the factors influencing farmers’ willingness to engage in LC production through multiple regression analysis. Additionally, a structural equation model was employed to examine the relationship between farmers’ internal motivation and LCPB. Drawing upon the results and analysis of the research, policy suggestions have been put forth to stimulate and endorse carbon-efficient production practices within the farming community.

Establishing the context: a review of the literature and assumptions

Literature review

The link between human actions and the environment is inseparable. There are two types of LC behavior, which are private and public LC behavior (Chen and Li 2019). The research paper investigates private LCPB among farmers, which consists of five behaviors: employing biological pesticides, utilizing organic fertilizers, recycling agricultural wastes, practicing LC management, and implementing LC technologies. In order to explicate the mechanics of environmentally friendly behavior, four theories of advancement have been proposed, including Planned Behavior Theory (TPB), Norm Activation Model, Value-Belief-Norm Theory, and Attitude-Behavior-External Condition Model. TPB operates on the assumption of rational actor theory (Guagnano et al. 1995). The widely used psychological framework known as Planned Behavior Theory (TPB) can aid in identifying the factors that impact particular behaviors in distinct contexts, such as LC behaviors (Borthakur and Govind 2018; Ding et al. 2018). In accordance with this theory, the intention to act has a significant impact on the behavior that is exhibited. This intention is influenced by behavioral attitudes, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, and the interaction between these factors (Ajzen 1991). TPB provides a model about the determinants of individual behavior (Ajzen 1991). According to TPB model, an individual’s behavior is determined by his or her behavior willingness, which depends on three factors. The first psychosocial factor is behavioral attitude, which is an individual’s positive or negative evaluation of behavior. The second is subjective norm (SN), which refers to an individual’s estimate of social pressure to take action or not to take action. The third is perceived behavior control (PBC), which refers to judging the difficulty of engaging in a certain behavior according to one’s own experience and expectations.

Although TPB has universal practicability, many researchers try to expand its explanatory power and practical application by adding additional structures to TPB models. TPB’s extended theory is widely used to study the transition to a more sustainable and environmentally friendly lifestyle (Conner and Armitage 1998; Han et al. 2010; Paul et al. 2016; Shi et al. 2017). The general results of previous studies show that the factors not specified in the basic TPB model increase the explanatory power of the model and lead to providing more information for decision-making. In this paper, the motivation variable is added to the original TPB model to enhance the model’s explanation of reality.

It is generally believed in the theoretical circles that the external incentive effect on individual behavior is quick, but the duration is short; internal motivation is just the opposite. Although it works slowly, the change of behavior is long-term. As far as farmers’ LCPB is concerned, their internal motivation is often fragile. When external incentives exist, the external motivation will crowd out the internal motivation of farmers’ LC behavior, especially economic incentives, which will lead to changes in people’s values and psychological tendencies, and this change is often long-term. Intrinsic motivation and external environmental changes jointly influence farmers’ behavior decision-making, and the effect of behavior decision-making may also be different (Ma and Chan 2014; Newman and Fernandes 2016).

Carbon-efficient production practices adopted by farmers are influenced by various factors, including internal and external motivation. However, due to the “discount law” (also known as “over justification effect”), individuals may disregard their internal motivation and focus excessively on external motivation (Zhang and Guo 2003). Yao et al. (2016) put forward a theoretical framework that includes “economic rationality” and “ecological rationality,” trying to find the behavioral logic of farmers’ adoption of protective cultivated land technology from the internal psychological mechanism. Some scholars clearly distinguish the differences between economic individuals’ psychological cognition and behavior and are constrained by limited rationality caused by incomplete cognition and uncertain external environment, and farmers have insufficient motivation to adopt straw returning technology (Zhang et al. 2019). Policy-oriented farmers’ LC behavior focuses on external incentives to farmers, often ignoring the existence of internal motivation of farmers’ own environmental protection behavior. This kind of compensation method not only increases the financial burden of the country, but also is not conducive to the formation of farmers’ long-term agricultural environmental protection behavior. Internal motivation is not the difference between “again” and “nothing,” but the difference between strong and weak (Pelletier et al. 1997). Economic incentives are not the only way to promote the development of low carbon agriculture and may not even be an economical and effective way.

Currently, the primary focus of research on farmers’ LCPB is centered on determining the factors that influence such behavior (Ding et al. 2018; Nisa et al. 2019; Yang et al. 2020). This research also highlights the significance of LC agricultural technology (Freibauer et al. 2004; Kroodsma and Field 2006; Norse 2012; Vinholis et al. 2021), explores farmers’ adoption of LC agricultural technology (Shang and Yang 2021; Zhao and Zhou 2021), examines the corresponding adoption effect (Johnson et al. 2009; Norse 2012; Fan and Wei 2016; He et al. 2021), and delves into the development path of these technologies (Arima et al. 2014; Rees et al. 2016; Piwowar 2019; **ong et al. 2021).

In a word, although there have been many studies on LC behavior, there are still four limitations. (1) Most of the previous studies focused on residents’ LC behavior or LC purchase behavior, but there were few studies on farmers’ LCPB, and there were obvious regional differences due to the different terrain, climate, and socio-economic development conditions, which were not properly focused. (2) The majority of literature fails to acknowledge the role that farmers’ carbon-efficient production practices play in curbing agricultural carbon emissions and their significance in attaining the objective of reaching peak carbon dioxide emissions by 2030 and achieving carbon neutrality by 2060. (3) In previous studies, Probit, Tobit, Logit, Bootstrap, and hierarchical regression methods were used to test the mediating effect and regulating effect of a certain variable step by step (**ang et al. 2020). These models do not have a theoretical framework to combine and accommodate the relationships among various potential impacts of LC behaviors. (4) Previous literatures have paid more attention to the process of LC willingness changing into LC behavior but have not paid attention to the long-term influence of internal motivation on farmers’ behavior.

Assumptions

The TPB theory was proposed by Ajzen, drawing upon the Rational Action Theory (Ajzen 2005). The actual behavior is determined by both motivation (intention) and ability (behavior control). In this paper, farmers’ internal motivation is divided into internal motivation based on joy and internal motivation based on responsibility, which are incorporated into TPB theoretical model. An analytical framework has been developed to investigate the carbon-efficient production practices adopted by farmers, thus augmenting the model’s capacity to explain real-world phenomena.

Internal motivation, behavior attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavior control are used to predict behavior. Internal motivation refers to the motivation generated by an individual's interest in the activity itself. Individuals do not need external forces to engage in this activity, and the internal motivation is adaptive (Zhang and Guo 2003), which is often described as the reason, purpose, and strength of people’s behavior. Behavior attitude refers to an individual’s personal evaluation of a specific behavior, either positively or negatively. Another predictor is a social factor called subjective norm, which refers to the social pressure an individual feels to perform or not perform a particular behavior. Perceived behavior control is the third predictor, which refers to the perceived difficulty of performing the behavior, reflecting past experiences, expected obstacles, and barriers. Generally, the more favorable the attitude and subjective norm towards a particular behavior, the stronger the perceived behavior control, and the stronger the intention to perform the behavior. Based on the research discussed in this paper, the following assumptions are proposed.

-

H1: FLCB is directly affected by their internal motivation.

-

H1a: FLCB is directly influenced by internal motivation based on joy.

-

H1b: FLCB is directly influenced by internal motivation based on responsibility.

-

-

H2: FLCB is directly influenced by their behavior attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavior control.

-

H2a: FLCB is directly influenced by behavior attitude.

-

H2b: FLCB is directly influenced by subjective norm.

-

H2c: FLCB is directly influenced by perceived behavior control.

-

-

H3: Internal motivation based on joy and internal motivation based on responsibility are associated with behavior attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavior control.

-

H3a: The internal motivation based on joy and the internal motivation based on responsibility influence each other.

-

H3b: The internal motivation and behavior attitude based on joy influence each other.

-

H3c: The internal motivation based on joy and subjective norm influence each other.

-

H3d: Internal motivation based on joy and perceived behavior control influence each other.

-

H3e: Internal motivation based on responsibility and behavior attitude influence each other.

-

H3f: Internal motivation based on responsibility and subjective norm influence each other.

-

H3g: Internal motivation based on responsibility and perceived behavior control influence each other.

-

-

H4: Behavioral attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavioral control are interrelated

-

H4a: There is an interactive relationship between behavioral attitude and subjective norm.

-

H4b: There is an interactive relationship between behavior attitude and perceived behavior control.

-

H4c: There is an interactive relationship between subjective norm and perceived behavior control.

-

Research methodology

Research sites and samples

Shaanxi Province is located in the northwest of China, connecting the eastern, central, and western regions, with a unique geographical position. According to the statistics of Shaanxi Provincial Bureau of Statistics, the cultivated land in Shaanxi Province is 2,934,300 hectares (44,015,100 mu). Among them, dry land is 1,964,200 hectares (29,464,300 mu), accounting for 66.94%. Eighty-one percent of cultivated land is distributed in northern Shaanxi Plateau and Guanzhong Plain. Yulin City, Weinan City, ** green economy. The Loess Plateau in northern Shaanxi is criss-crossed, with barren land and serious soil erosion, which is suitable for develo** ecological agriculture with soil and water conservation. In this study, 13 counties in Baoji City, **anyang City, Weinan City, Tongchuan City, and **an City were randomly sampled and 260 valid questionnaires were collected, including 102 in Baoji City, 57 in **anyang City, 42 in Tongchuan City, 40 in Weinan City, and 19 in **’an City. Each questionnaire is completed under random and independent conditions, because behavioral attitude and subjective norm predict intentions better under the condition of careful reaction than under the comparative condition. Figure 1 shows cultivated land and carbon emission of cities in Shaanxi Province.

Structural equation model (SEM)

SEM offers more advanced analysis of the relationship between potential and observed variables compared to the general regression model. SEM allows for the investigation of complex relationships between potential variables (Wang et al. 2019). The SEM consists of two models, the structural model and the measurement model, which are commonly expressed as follows:

In Eq. (1), the variable η is a latent variable, while δ is an exogenous latent variable, and Λ and Γ are the path coefficients. The residual term is represented by γ. Equation (2) is the measurement model that describes the relationship between each latent variable and its observed variable. The observed variables of the exogenous latent variable are X and Y, and δ and η are the endogenous latent variables. The factor loading matrix of observed variables to latent variable δ is represented by ΛX, and the factor loading matrix of observed variables to latent variable η is represented by ΛY. The residual terms of the exogenous and endogenous variables are represented by ξ. The structural equation model (SEM) is useful in exploring the intricate relationships between latent and observed variables and can provide more insights than the general regression model (Wang et al. 2019).

Factor analysis is a statistical method that can extract essential information from multiple variables while minimizing information loss ((Dong et al. 2020; Zaleski and Michalski 2021). The method is designed to group variables based on their correlation, with variables in the same group having a high correlation, while variables in different groups have a low correlation. These groups of variables are referred to as common factors, and they reveal important information about the data.

Questionnaire design and socioeconomic characteristics

This research questionnaire adopts a 5-item scale adapted from Ali et al. (2020) and Li and Li (2019) to measure the internal motivation, external motivation, behavior attitude, subjective norm, perceived behavior control, behavior willingness, and LC behavior. The questionnaire collected information about farmers and their families from four parts. (1) Basic information of interviewees, including individual characteristics, family characteristics, planting characteristics and trends, external conditions, and social capital, such as gender, age, education level, cultivated land area, whether to attend training, mobile phone contacts, whether to join cooperatives, relationship with neighbors, summary of relatives within three generations, etc. (2) Farmers’ LC cognition and social norm, to investigate farmers’ cognition level of agricultural LC production, and to know the LC behavior standards of surrounding members. (3) The internal motivation, LCPB attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavior control of farmers’ LC behavior. (4) Investigating farmers’ LC production willingness, and actual adoption behavior. Researchers conducted a field survey in the form of face-to-face interviews with families and collected 260 valid questionnaires.

Basic characteristics of interviewees

A total of 260 households were interviewed, with an average household population of 3.85, with only 1.78 farming member in the household, and 88.5% of the interviewees were heads of households, so they knew more about the family situation and planting situation. The respondents accounted for 88.8% of men and 11.2% of women. 98.1% of the respondents’ household registration is rural household registration.

Most of the farmers interviewed are middle-age or elder; 97% is over 45 years. The interviewed farmers have an average age up to 61.36 years old, whereas maximum and minimum ages are 93 and 30, respectively. Of the interviewed farmers, 16.2% have never been to school; with primary school education account for 22.3%; with junior high school education, being the most common, account for 47.7%; and with senior high school education or above account for 13.8%. Among the farmers interviewed, village cadres accounted for 5.8%, and party member farmers accounted for 10.4%. The average annual income of the interviewed households is 52,000 yuan, and the average agricultural income is 10,000 yuan.

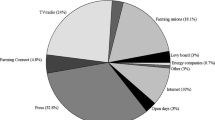

Production and sales

Shaanxi is located in the northwest of China. The average planting area of ordinary farmers is 10.11 mu, mainly are wheat, corn, apples, and kiwi fruit. The average planting years of the interviewed farmers are 38.84 years. More than half of the users think that the prices of future crops are similar to the current ones, accounting for 52.69% of the sample size. Of the interviewed farmers, 84.62% indicated that they would not expand the planting area, mainly because of the rural land allocation policy and their unwillingness to bear the economic burden brought by contracted land. Farmers’ sales channels mainly rely on vendors’ street-to-street sales, accounting for 75.38% of the sample size. Of the farmers, 27.69% think that natural disasters are the biggest threat to planting, and the remaining risks are unstable selling price, low yield, difficulty in selling, lack of equipment, and complicated field management, and 14.62% of the farmers think that there is no planting risk. Of the farmers, 72.69% think that the difficulty of selling crops is easy and very easy. Only 34.2% of the farmers surveyed have purchased agricultural insurance, and most of them are kiwifruit and apple growers. The responses to the 24 items were categorized into 5 dimensions, and their levels and structures are illustrated in Fig. 2.

Testing of reliability and validity

The total scale reliability includes 53 items, including internal motivation, LC cognition, LC behavior, and social norms. The subscale reliability consists of the measurement items of subscale. The reliability of the total scale is 0.854, and the reliability of the subscales are all above 0.7 (0.758–0.981), which indicates that the questionnaire structure is good (Table 1).

Results

Analysis of the internal motivating factors behind LCPB among farmers

Internal motivation measurement

The reliability values of internal motivation dimension of FLCB are 0.944 and 0.819 (Table 2), the scale has high reliability, and the measurement variables are set reasonably. Bartlett spherical test and KMO test show that the eight measurement variables of internal motivation are more suitable for factor analysis.

The relationship between internal and external motivation

Pearson correlation coefficient is used to examine the compatibility between internal motivation and external motivation of FLCB.

The internal motivation and external motivation of farmers’ LCPB are highly correlated within the dimension, while the cross-dimensional correlation weakens or becomes negative. The internal motivation based on joy is negatively correlated with the variable EM3 in external motivation (is bio-pesticide used to avoid the punishment of local government), and positively correlated with other variables in external motivation (as shown in Table 3). Internal motivation based on responsibility is negatively correlated with the variable EM3 in external motivation (is bio-pesticide used to avoid the punishment of local government), and positively correlated with other variables in external motivation (as shown in Table 4).

The above-mentioned correlation analysis shows that there is a negative correlation between internal motivation and external motivation variable EM3 (is bio-pesticide applied to avoid the punishment of local government), which may be due to the lack of relevant punishment policies of local government. Both the internal motivation based on joy and the internal motivation based on responsibility are positively correlated with other variables in external motivation.

Analysis of factors influencing farmers’ internal motivation of LCPB

The influencing factors of internal motivation of farmers’ LCPB are mainly discussed in the following aspects: individual characteristics 7, family characteristics 4, planting characteristics 3, external conditions 2, social capital 4, LC cognition 7, and social norms 3. A total of 30 models are as follows:

Among them, I1, I2 represent internal motivation based on joy and external motivation based on responsibility, Individuality represents individual characteristics of farmers, Family represents family characteristics of farmers, Planting represents planting characteristics of farmers, External-condition represents external factors, Social-capital represents social capital of farmers, Cognition represents LC cognition of farmers, and Social-Norm represents social norms of farmers.

Taking 30 variables of individual characteristics, family characteristics, planting characteristics, external conditions, social capital, LC cognition, social norm, and other dimensions as independent variables, the internal motivation based on pleasure feeling as dependent variables makes regression analysis. The results show that there is no serious collinearity problem among the independent variables (VIF “variance inflation factor” is between 1.170 and 1.995), and the regression fit is good, R2 = 0.399. Among the independent variables included, it has statistical significance on the internal motivation based on pleasure (P < 0.05).

According to Table 5, age, household registration type, agricultural labor force, planting training, and LC cognition, and social norm have a significant positive impact on farmers’ internal motivation based on joy. At the same time of blessing various rights and interests in agricultural-registered permanent residence, with the growth of age and the increase of agricultural labor force, farmers’ feelings and connections for agriculture are strengthened, and farmers’ internal motivation based on joy is stronger. Training has a significant positive impact on farmers’ internal motivation based on joy; consistent with expectations, farmers’ LC cognition and social norm with a significant positive effect on the farmers’ internal motivation based on joy. Contrary to expectations, social capital with negative effect on the farmers’ internal motivation based on joy, which may be due to the limited psychological intervention of neighbors and relatives, and most farmers’ psychological satisfaction comes from themselves. It should be noted that the influence direction of the status of party member and village cadres is inconsistent with expectations, which may be the reason why there are fewer farmers with the status of party member and village cadres in the sample. There are only 15 village cadres and only 27 in party member in the sample. The influence direction of planting years is inconsistent with expectations. According to the actual investigation, planting is only a means of survival for the elderly farmers, and it does not matter whether they are happy or not. Moreover, the older farmers have lower labor ability and pay more attention to income, so they don't think that LC production of farmers is a pleasant thing. The influence direction of annual household income is inconsistent with the expectation, because most of the income of farmers with more annual household income comes from non-agricultural income, and the pleasure brought by agricultural production is minimal. However, agricultural insurance has a negative impact on the internal motivation of farmers’ happiness, mainly because the popularization of agricultural insurance was not standardized at first, and the claims were not settled in time, resulting in poor experience of farmers.

Factors such as education level, social capital, LC cognition, and social norms have a noteworthy positive impact on farmers’ intrinsic motivation, which is grounded in a sense of responsibility. Among them, higher education level enhances the farmers’ internal motivation based on responsibility. However, social capital has a negative impact on farmers’ internal motivation based on responsibility, contrary to expectations; LC cognition and social norms can significantly promote farmers’ internal motivation based on responsibility. It is worth noting that the influence of planting years and ages on farmers’ internal motivation based on responsibility is inconsistent with expectations. In reality, older farmers have lower labor ability and pay more attention to survival. The impact of agricultural insurance on farmers’ internal motivation based on joy and responsibility is inconsistent with expectations, which may be due to the low payout ratio and low compensation amount of agricultural insurance in the actual situation. Farmers’ LC production needs to meet basic material needs such as “food, clothing, housing and transportation” first, and then they will weigh the economic utility brought by income against the satisfaction brought by LC agricultural production.

Analysis of influencing factors of farmers’ LCPB intention

The KMO (= 0.859) and Bartlett spherical test results of farmers' LC intention show that five variables are suitable for factor analysis, and the factor analysis results show that there is only one dimension in five variables. The factor coefficients are all greater than 0.7, which indicates that all measurement dimensions can well reflect the farmers’ LC behavior intention. Cronbach’s alpha value is 0.908, which indicates that the measured variables have high reliability. Descriptive statistics show that FLCB intention is strong, and the average values of five measurement variables are all greater than 3, of which 61.15% are willing and very willing to choose LCPB, 60.77% are willing and very willing to use LC biological pesticides instead of general pesticides, 62.31% are willing and very willing to use LC organic fertilizer instead of general chemical fertilizer, and 75.38% are willing and very willing to recycle agricultural production wastes. Farmers who are willing and very willing to learn LC management technology account for 58.08%. On the whole, the cumulative proportion of those who are willing and very willing to recycle agricultural production wastes is the highest among the five variables, which may be due to the low cost of this kind of behavior.

In Table 6, the R square of the model is 0.647; that is, the variance explanation rate of independent variables to dependent variables is 64.7%, and the DW value is 1.757, which is close to 2. It is considered that the variables have no auto-correlation, and the significance is 0.000, which is determined by individual characteristics, family characteristics, planting characteristics, external conditions, social capital, LC cognition, social norms, internal motivation based on joy, internal motivation based on responsibility, external motivation, behavior attitude, and social norm. The results show that the independent variables have no serious collinearity problem, and the regression fitting is good, R2 = 0.647. Among the independent variables included, the influence on FLCB intention is statistically significant.

In Table 7, the aspects that have significant impact on FLCB intention are family size, internal motivation based on joy, external motivation, behavior attitude, subjective norm, perceived behavior control, the number of mobile phone contacts, and the relationship with neighbors. The larger the number of families, the greater the survival pressure of farmers, and thus, the lower their willingness to act. The internal motivation based on joy has a significant impact on FLCB intention, which shows that for most farmers interviewed, LC behavior is more driven by pleasure than constrained by sense of responsibility. The external motivation of the interviewed farmers also significantly affects their LC behavior intention. At the same time, the LC behavior attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavior control of the interviewed farmers have a significant positive impact on their LC behavior intention which is the same with expectations. At the same time, the more the number of mobile phone contacts of the head of household, the more general the relationship with neighbors; the more obvious the farmers’ LC intention, mainly because the more contacts, the more sources of information the head of household receives; and the more general the relationship with neighbors, the more inclined they are to get information through other channels, such as TV and mobile phones. Education level has a negative impact on farmers’ LC behavior intention, which is inconsistent with expectations. The possible reason is that most of the interviewed farmers have low education level, and only 2.7% of the interviewed farmers have college degree or above. The results show that age has a negative impact on farmers’ LC behavior intention, but it is not significant, which may be due to the fact that with the increase of age, the old people’s cognition of new things cannot be synchronized, and some old people are more concerned about survival. The results show that the more land you own, the more reluctant you are to carry out LC production, probably because of the cost. The more land you own, the higher the cost of LC production. At the same time, the longer the planting years, the more reluctant they are to engage in agricultural LC production, mainly because the traditional ideas are deeply rooted and they do not think their agricultural production can play much role. Whether or not you have participated in planting training has an inconsistent impact on farmers’ LC intention, mainly because most of the current training focuses on the popularization of technology, which more affects farmers’ familiarity with various agricultural technologies and equipment than their awareness of LC technology or LC management. However, whether or not to join the cooperative has a positive impact on farmers’ LC behavior intention, which is consistent with expectations, but not significant. The influence of capital on farmers’ willingness to LC behavior is negative, mainly because the interaction between the interviewed farmers and the outside world is extremely limited, and the social network is relatively simple. The impact of social norms on farmers’ willingness to LC behavior is not same with expectations, and it has a negative impact. The main reason is that most of the interviewed farmers said they did not know whether village cadres, demonstration households, or relatives and neighbors had LC behavior in agricultural production, or directly denied that village cadres, demonstration households, or relatives and neighbors had LC behavior in agricultural production.

Impact of internal motivation on farmers' LCPB

At present, the academic circles are mainly divided into two types to study the behavior of the target object. One is to study the behavior of the target object with willingness as the proxy variable, and the other is to study the behavior of the target object directly. Although it is generally believed that the premise of behavior is intention, in reality, it takes certain conditions for intention to be transformed into behavior. Obviously, intention is not the same as behavior. This paper has discussed farmers’ LC behavior intention; therefore, farmers’ LCPB in this paper is farmers’ real behavior, not their intention.

Table 8 presents the goodness-of-fit index for the SEM model, with a chi-square ratio (436.644) to degrees of freedom (193) of 2.447, falling within the acceptable range of 1–3. At the same time, other specific indicators, such as RMSEA, CFI, GFI, TLI, PNFI, and PGFI, have reached an acceptable range (Yin and Shi 2021). Thus, the SEM is an ideal fitting model, which is reasonable and effective for analyzing the influence mechanism of farmers’ LC behavior.

In order to verify the hypothesis between the internal motivation, behavior attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavior control and farmers’ LC behavior in the theoretical model, this study builds a structural equation model through AMOS22.0 software, and tests the theoretical hypothesis put forward in this study according to the path analysis results. The established structural equation model is shown in Fig. 3, including measurement model, structural model, and corresponding path coefficients.

Structural equation model path analysis diagram. Note: IMJ stands for internal motivation based on joy, IMR stands for internal motivation based on responsibility, BA stands for behavior attitude, SN stands for subjective norm, PBC stands for perceived behavior control, and LCB stands for farmers’ LC behavior

From the path analysis results (Fig. 3.), it can be found that the structural equation model results verify the hypothesis H1, H2, H3, and H4 mentioned above, and the summary of hypothesis test results is shown in Table 9.

Multi-group analysis

A multi-group analysis was carried out to identify potential dissimilarities in the influence mechanism of carbon-efficient behavior among groups with varying demographic characteristics. The observation results were divided into two groups based on each fault removal factor. The estimated coefficients of 14 models’ influence paths for different groups are presented in Table 10, including education level below and above middle school, family income < 50,000 yuan and family income ≥ 50,000 yuan, agricultural income < 5000 yuan and agricultural income ≥ 5000 yuan, planting area ≤ 5 mu and planting area > 5 mu, planting years ≤ 35 years and planting years > 35 years, attendance at training sessions, and purchase of agricultural insurance. The chi-square test confirmed the validity of all models based on their p value.

The results of the fourteen models reveal significant differences in their action mechanisms and provide some insightful findings. These mechanisms are consistent with the results obtained from the analysis of 260 questionnaires, in terms of their interrelationships. In all 14 models, the interaction paths of IMJ and IMR, IMJ and BA, IMJ and SN, IMR and BA, IMR and SN, BA and SN, BA and PBC, and SN and PBC are all significant.

Further interpretation will now be provided to discuss the distinct features of the 14 models’ paths. Firstly, compared with those with middle education or below, the LCPB of farmers is significantly positively impacted by the subjective norm and perceived behavior control of the group with middle junior school and above education levels. Additionally, the LCPB of farmers in the middle school and below groups is significantly influenced by their internal motivation based on joy. Secondly, the finding indicates that farmers with middle junior school and above education levels are positively influenced by subjective norms and perceived behavior control when it comes to LCPB. The farmers with household incomes above 50,000 yuan are positively influenced by internal motivation based on joy, while those with household incomes below 50,000 yuan are positively influenced by subjective norms and perceived behavior control. The finding reveals that farmers with agricultural incomes less than 5000 yuan are positively influenced by internal motivation based on responsibility, while those with agricultural incomes higher than 5000 yuan are positively influenced by internal motivation based on joy. The finding highlights that when the planting area of farmers is ≤ 5 mu, internal motivation based on responsibility, behavior attitude, and subjective norm have a significant impact on LCPB. The finding shows that internal motivation based on joy of farmers whose planting years are less than or equal to 35 years has a significant positive impact on their LCPB, while internal motivation based on responsibility of farmers whose planting years are more than 35 years has a significant positive impact on their LCPB. The finding indicates that compared to farmers who have participated in agricultural training, those who have not participated are more significantly influenced by internal motivation based on joy, internal motivation based on responsibility, and perceived behavior control with regard to LCPB. The finding suggests that internal motivation based on responsibility of the groups who have bought agricultural insurance has a significant impact on farmers’ LCPB, while internal motivation based on joy and perceived behavior control of the groups who have not bought agricultural insurance have a significant impact on their LCPB.

Discussion

LC production practices in agriculture refer to the actions and strategies that farmers and agricultural organizations take to reduce their carbon emissions and mitigate the impacts of climate change. Examining the motivations behind these practices is important for understanding how to effectively promote sustainable development and address climate change through the attainment of LC goals. One motivation for LC production practices in agriculture is the potential for economic benefits.

The study has uncovered significant results that require further discussion. Initially, a theoretical structural model was created to scrutinize the factors that impact carbon-efficient production practices. The structural model is designed by TPB theory and motivation theory. Internal motivation is divided into internal motivation based on joy and internal motivation based on responsibility.

Internal motivation refers to the personal reasons or drivers that lead individuals or organizations to engage in certain behaviors. In the context of LC production practices in agriculture, internal motivation can be based on two main drivers: joy and responsibility. Examining these drivers is important for understanding how to effectively promote sustainable development and address climate change through the attainment of LC goals.

Internal motivation based on joy refers to the personal satisfaction and enjoyment that individuals or organizations may experience from engaging in LC production practices. A study by Van der Ploeg et al. (2019) found that farmers who had an intrinsic interest in environmental conservation were more likely to adopt sustainable farming practices, such as agroforestry, and reported higher levels of satisfaction with their work. Another study by Peeters et al. (2021) found that farmers who had a positive attitude towards sustainable agriculture were more likely to adopt LC production practices, such as precision agriculture, and experienced greater levels of well-being.

Internal motivation based on responsibility refers to the sense of moral or ethical obligation to address climate change and promote sustainable development. A study by Darnhofer et al. (2018) found that farmers who had a strong sense of social responsibility were more likely to adopt LC production practices, such as precision agriculture, as a means of reducing their environmental impact. Another study by Bindraban et al. (2019) found that farmers who had a strong sense of environmental stewardship were more likely to adopt sustainable practices, such as conservation agriculture, as a means of mitigating the impacts of climate change.

Both internal motivations, joy and responsibility, can drive farmers and agricultural organizations to adopt LC production practices; however, the study of Peeters et al. (2021) suggests that motivation based on joy may lead to more sustained engagement over time.

Meanwhile, social capital, external motivation, LC cognition, and social norm are investigated. At the same time, farmers’ LC production intention and behavior are also investigated. Compared with previous structural models (Chen and Li 2019; Gunarathne et al. 2020), the model is richer and more perfect. At the same time, the path and the corresponding hypothesis are verified by the results, and it is confirmed that the internal motivation plays an important role in the process of intention to action. Studies indicate that enhancing intrinsic motivation can concurrently promote carbon-efficient attitudes and practices, which is in line with prior research (Kaffashi and Shamsudin 2019; Wang 2019; Liu 2021; Yang 2021; Zhao et al. 2022).

Secondly, this survey found that farmers’ awareness, concern, and practice of LC issues in Shaanxi Province are relatively low (Ren 2015). Given its status as a developed province in the western region, Shaanxi should set an example and lead the way, but the actual situation is the opposite. The behavior of individuals is largely influenced by their intentions. The scores for carbon-efficient intentions among farmers in Shaanxi Province were found to be higher than their behavior scores, indicating the possibility of a potential increase in the adoption of LC practices in the future. This suggests that the implementation of carbon-reducing policies and measures in Shaanxi Province has been effective in promoting sustainable behavior.

The primary aim of this study was to explore the factors that impact carbon-efficient practices among farmers. Results indicate that both intrinsic motivations based on pleasure and responsibility significantly influence farmers’ adoption of LC production methods (Wang 2019; Li 2020; Yang et al. 2022). LC production attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavior control have a significant impact on farmers’ LCPB. Internal motivation based on joy, internal motivation based on responsibility, behavior attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavior control influence each other (Wiium et al. 2006). Multi-group analysis shows that different groups’ internal motivation based on joy and internal motivation based on responsibility have not all significant effects on LCPB. The actual situation of farmers’ LCPB in Shaanxi Province is not ideal. The main reason is that hypnotic effect prevents administrative regulations and policies from doing what they want (Asensio and Delmas 2016). The findings suggest that certain policies and regulations may have shortcomings in both their formulation and implementation, indicating the need for appropriate modifications and continued application.

In summary, recent literature suggests that internal motivation based on joy and responsibility can play a significant role in driving farmers and agricultural organizations to adopt LC production practices as a means of addressing climate change and promoting sustainable development. Motivation based on joy may lead to more sustained engagement over time. Identifying and addressing these motivations can be an effective approach to encouraging the adoption of LC production practices in agriculture. These motivations are critical in addressing climate change and promoting sustainable development through the attainment of LC goals.

This study deeply discusses the “black box” that supports the relationship between internal motivation and farmers’ LCPB. Farmers’ LCPB is a non-compulsory voluntary behavior, and it usually takes extra time or money to carry out LC production (Li 2020; Wu 2021; Jiang et al. 2022). Therefore, intrinsic motivation is the mechanism that affects farmers’ LCPB. This study reveals that internal motivation is a spiritual medium, and LC cognition has changed farmers’ view on how LC production mode can meet their psychological needs, which in turn leads to the change of personal internal motivation and ultimately affects farmers’ LCPB.

While this research has yielded valuable findings, there remain several limitations that must be addressed in future studies. First, the original data was collected using a questionnaire survey. This inevitably leads to the deviation of the mechanism affecting LC behavior. While this study provides valuable insights, there are several limitations that must be addressed in future research. Firstly, the data was collected through a questionnaire survey, which may have limitations in terms of accuracy and scope. Therefore, future studies should consider more precise and extensive data collection methods to improve the results. Secondly, this study employed a consistent hypothetical structural model for multi-group analysis. However, it is important to note that the factors influencing LC behavior may differ across various groups. While this study focused on farmers in Shaanxi Province, future research should develop specific models to verify the influence mechanism of different groups. To enhance the accuracy of future research, it is recommended to conduct more extensive and precise investigations. Additionally, the study employed a consistent hypothetical structural model for multi-group analysis, while in reality, different groups may have different mechanisms affecting LC behavior. Although this study focused on the influence mechanism of farmers’ LCPB in Shaanxi Province, it did not develop a specific model to verify the influence mechanism of different groups. Future studies could investigate more specific paths and structural models and propose more targeted policy suggestions based on research findings. Lastly, this study considered 7 dimensions and 29 items of the questionnaire, and it is suggested that future studies could incorporate more dimensions and items in assessing LC behavior. The research on LC behavior should include more scientific disciplines. Despite these limitations, this study is helpful to understand LC behavior and its influencing factors, thus contributing to LC development.

Concluding remarks

The study outcomes demonstrate, firstly, that farmers’ LCPB is significantly influenced by both their internal motivation based on joy and their internal motivation based on responsibility. Thus, it is essential to mentor farmers who have strong intrinsic motivation toward LCPB development. The fulfillment of the demands for autonomy, ability, and relationship are prerequisites for the development of intrinsic motivation. Among these three psychological needs, the relationship is more easily affected by the policy. This research thus recommends that the establishment of agricultural infrastructure by the government and enterprises will strengthen farmers’ sense of social support. By doing so, we can address the corresponding psychological needs. For example, the provision of LC biological pesticides and organic fertilizers. On the other side, through increased feedback, policies should direct the people toward greater environmental identity awareness. For example, the government and enterprises should award honorary titles to outstanding LC production participants, thus giving them intangible rewards. There is a “consciousness-behavior gap,” that is, LC consciousness can slightly regulate LCPB through psychological factors. Secondly, the internal motivation based on responsibility has a stronger influence on farmers’ LCPB than other factors. Individual LCPB is influenced by many factors, and the mechanism is complex. The findings demonstrate that the internal motivation based on responsibility has a greater impact on farmers’ LCPB than other factors. As a result, it is important to increase farmers’ knowledge of LC production and their sense of ownership. The award of honorary title makes farmers experience the value brought by the sense of responsibility. Thirdly, different groups' internal motivation based on joy and internal motivation based on responsibility have different influences on farmers’ LCPB. Therefore, different drugs should be given to different groups, and one size fits all. For example, for farmers whose family income exceeds 50,000 yuan and farmers whose agricultural income exceeds 5000 yuan, we will take paid measures to promote LC production and related LC products and subsidize low-income groups to increase the recycling price.

This study’s results offer policy suggestions for policymakers to achieve effective and LC development. The government should prioritize the significance of farmers’ LCPB, which can play a crucial role in achieving LC objectives. Under the background of LC development, the awareness and behavior of farmers in Shaanxi Province have great room for improvement. Policymakers and managers must continue to strengthen farmers’ attitude towards LC production and guide their behavior in LC production. It is necessary to strengthen the popularization of LC knowledge and LC production education for farmers, so as to promote farmers’ LC production. In addition, traditional media and new media are used to encourage LC production publicity activities, to improve farmers’ positive attitude towards LC production. The specialties concerned must enhance their monitoring during the formulation and implementation of policies. As farmers in Shaanxi Province have limited knowledge of low carbon, policies and regulations should be optimized, and more precise measures should be implemented to raise awareness among the farmers. Third, considering the local differences, it is important to explore options for providing diverse technical equipment and technical instructors on-site., so as to popularize LC management and LC technologies while solving the actual needs of farmers. Fourthly, it is essential to tailor technical equipment and technical instructions based on local differences. Policies and regulations should also be flexible and consider local customs and conditions. One-size-fits-all policies should be avoided, and specific policies should be formulated for different groups. For instance, subsidies could be provided to low-income groups by increasing the recycling price.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Aguilera E, Reyes-Palomo C, Díaz-Gaona C, Sanz-Cobena A, Smith P, García-Laureano R, Rodríguez-Estévez V (2021) Greenhouse gas emissions from Mediterranean agriculture: Evidence of unbalanced research efforts and knowledge gaps. Glob Environ Chang 69:102319

Ajzen I (1991) The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 50:179–211

Ajzen I (2005) EBOOK: Attitudes, Personality and Behaviour. McGraw-hill education (UK)

Ali MAS, Yi L (2022) Evaluating the nexus between ongoing and increasing urbanization and carbon emission: a study of ARDL-bound testing approach. Environ Sci Pollut Res 29:27548–27559

Ali F, Ashfaq M, Begum S, Ali A (2020) How “Green” thinking and altruism translate into purchasing intentions for electronics products: The intrinsic-extrinsic motivation mechanism. Sustain Prod Consum 24:281–291

Arima EY, Barreto P, Araújo E, Soares-Filho B (2014) Public policies can reduce tropical deforestation: Lessons and challenges from Brazil. Land Use Policy 41:465–473

Asensio OI, Delmas MA (2016) The dynamics of behavior change: Evidence from energy conservation. J Econ Behav Organ 126:196–212

Bindraban PS, Kuyper TW, van der Meer F (2019) Climate-smart agriculture: A review of the state of the art. Agron Sustain Dev 39:1–13

Borthakur A, Govind M (2018) Public understandings of E-waste and its disposal in urban India: from a review towards a conceptual framework. J Clean Prod 172:1053–1066

Chen W, Li J (2019) Who are the low-carbon activists? Analysis of the influence mechanism and group characteristics of low-carbon behavior in Tian**, China. Sci Total Environ 683:729–736

Conner M, Armitage CJ (1998) Extending the theory of planned behavior: A review and avenues for further research. J Appl Soc Psychol 28:1429–1464

Cui P (2021) Evaluation of carbon emission reduction effectiveness of energy consumption in the Yellow River Basin and research on emission reduction potential. Nan**g Normal University, Nan**g

Darnhofer I, Balmann A, Gibon A (2018) Precision agriculture: opportunities and challenges for sustainability. Sustainability 10:1416

Deng Y (2022) Research on the impact of agricultural green technology progress on carbon emissions. Northwest A&F University

Ding Z, Jiang X, Liu Z, Long R, Xu Z, Cao Q (2018) Factors affecting low-carbon consumption behavior of urban residents: A comprehensive review. Resour Conserv Recycl 132:3–15

Dong F, Pan Y, Zhang X, Sun Z (2020) How to evaluate provincial ecological civilization construction? The case of Jiangsu province, China. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17:5334

Dube, K (2022) South African Hotels and Hospitality Industry Response to Climate Change-Induced Water Insecurity Under the Sustainable Development Goals Banner

Ethel AA (2021) Factors Influencing Water Resources Availability and Water Use Efficiency:evidence from Sub-Saharan Africa. Jiangsu University

Fan C, Wei T (2016) Effectiveness of integrated low-carbon technologies: Evidence from a pilot agricultural experiment in Shanghai. Int J Clim Change Strat Manag 8:758–776

Freibauer A, Rounsevell MD, Smith P, Verhagen J (2004) Carbon sequestration in the agricultural soils of Europe. Geoderma 122:1–23

Gao L (2020) An Empirical Study on the Relationship between Industrial Carbon Emissions and Economic Growth in Shaanxi Province. **’an University of Science and Technology, **’an

Guagnano GA, Stern PC, Dietz T (1995) Influences on attitude-behavior relationships: A natural experiment with curbside recycling. Environ Behav 27:699–718

Gunarathne AN, Kaluarachchilage PKH, Rajasooriya SM (2020) Low-carbon consumer behaviour in climate-vulnerable develo** countries: A case study of Sri Lanka. Resour Conserv Recycl 154:104592

Han H, Hsu L-TJ, Sheu C (2010) Application of the theory of planned behavior to green hotel choice: Testing the effect of environmental friendly activities. Tour Manage 31:325–334

Hao J, Chen L, Zhang N (2022) A Statistical Review of Considerations on the Implementation Path of China’s “Double Carbon” Goal. Sustainability 14:11274

He P, Zhang J, Li W (2021) The role of agricultural green production technologies in improving low-carbon efficiency in China: Necessary but not effective. J Environ Manage 293:112837

Hou J, Hou B (2019) Farmers’ adoption of low-carbon agriculture in China: An extended theory of the planned behavior model. Sustainability 11:1399

Huang X (2019) Research on the Influence of Capital Endowment and Government Support on Farmers' Adoption Behavior of Soil and Water Conservation Technology. Northwest A&F University

** G, Guo B, Deng X (2020) Is there a decoupling relationship between CO2 emission reduction and poverty alleviation in China? Technol Forecast Soc Chang 151:119856

Jiang L, Huang H, Zhang J, LuoY (2022) Research on Dual-path Intervention Strategies of Rice Farmers' Low-Carbon Production Behavior——A Grounded Analysis Based on More than 500,000 Words of In-Depth Interview Data. World Agriculture 76–86

Johnson TM, Alatorre C, Romo Z, Liu F (2009) Low-carbon development for Mexico. World Bank Publications

Kaffashi S, Shamsudin MN (2019) Transforming to a low carbon society; an extended theory of planned behaviour of Malaysian citizens. J Clean Prod 235:1255–1264

Khan ZA (2021) Study on the Factors Affecting the Growth of Agricultural Products Export in Pakistan. Northwest A&F University.

Kroodsma DA, Field CB (2006) Carbon sequestration in California agriculture, 1980–2000. Ecol Appl 16:1975–1985

Lei H (2021) Research on pro-environmental behavior of farmers' land use based on the inconsistency of binary interests. Northwest A&F University

Li L (2020) Research on the impact of non-agriculturalization of water resources on food production and countermeasures. Shandong Agricultural University, Shandong

Li W (2021) Research on the Change and Simulation of Urban and Rural Construction Land Use in Zhejiang Province Based on CA-Markov Model. Zhejiang University of Commerce and Industry

Li H, Li S (2019) Agricultural environmental protection behavior of farmers: from the perspective of motivation. Social sciences academic press (CHINA)

Lin G, Jiang D, Yin Y, Fu J (2023) A carbon-neutral scenario simulation of an urban land–energy–water coupling system: A case study of Shenzhen, China. J Clean Prod 383:135534

Liu M, Yang L (2021) Spatial pattern of China’s agricultural carbon emission performance. Ecol Ind 133:108345

Liu H (2021) Research on the driving mechanism of voluntary carbon reduction behavior of urban residents in Jiangsu Province. China University of Mining and Technology

Luo J (2021) Research on the Evaluation of Ecological Level of Light Industry in Shaanxi Province. Shaanxi University of Science and Technology

Ma WW, Chan A (2014) Knowledge sharing and social media: Altruism, perceived online attachment motivation, and perceived online relationship commitment. Comput Hum Behav 39:51–58

Masson-Delmotte V, Zhai P, Pirani A, Connors SL, Péan C, Berger S, Caud N, Chen Y, Goldfarb L, Gomis M (2021). Climate change 2021: the physical science basis. Contribution of working group I to the sixth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change 2

Newman TP, Fernandes R (2016) A re-assessment of factors associated with environmental concern and behavior using the 2010 General Social Survey. Environ Educ Res 22:153–175

Nisa CF, Bélanger JJ, Schumpe BM, Faller DG (2019) Meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials testing behavioural interventions to promote household action on climate change. Nat Commun 10:1–13

Norse D (2012) Low carbon agriculture: Objectives and policy pathways. Environ Dev 1:25–39

Paul J, Modi A, Patel J (2016) Predicting green product consumption using theory of planned behavior and reasoned action. J Retail Consum Serv 29:123–134

Peeters P, De Lange W, Van der Ploeg JD (2021) Positive attitudes towards sustainable agriculture as a driver of farmers’ well-being and adoption of sustainable practices. Sustainability 13:1544

Pei Y, Shi M and Xu W (2021) Research on the Development of Local Public Pension Security System--Based on the Perspective of Fiscal Sustainability. Nan**g University Press

Pelletier LG, Tuson KM, Haddad NK (1997) Client motivation for therapy scale: A measure of intrinsic motivation, extrinsic motivation, and amotivation for therapy. J Pers Assess 68:414–435

Piwowar A (2019) Low-carbon agriculture in Poland: Theoretical and practical challenges. Pol J Environ Stud 28

Rees RM, Barnes AP and Moran D (2016) Sustainable intensification: the pathway to low carbon farming? Springer, pp. 2253–2255

Ren Z (2015) Climate Change Adaptation Strategies and Sustainable Development Model Selection in Guanzhong Region. Shaanxi Normal University

Ren J (2021) Research on Influencing Factors and Hierarchical Structure of Low-Carbon Agricultural Technology Adoption by Tobacco Farmers in Shaanxi. Northwest A&F University

Shang G-Y, Yang X (2021) Impacts of policy cognition on low-carbon agricultural technology adoption of farmers. Ying Yong Sheng tai xue bao: J Appl Ecol 32:1373–1382

Shi H, Fan J, Zhao D (2017) Predicting household PM2. 5-reduction behavior in Chinese urban areas: An integrative model of Theory of Planned Behavior and Norm Activation Theory. J Clean Prod 145:64–73

Sikder M, Wang C, Yao X, Huai X, Wu L, KwameYeboah F, Wood J, Zhao Y, Dou X (2022) The integrated impact of GDP growth, industrialization, energy use, and urbanization on CO2 emissions in develo** countries: evidence from the panel ARDL approach. Sci Total Environ 837:155795

Tang H (2018) Research on carbon emission efficiency and emission reduction potential of land use in Northwest China. **njiang Agricultural University

UNDP (2011) Preparing Low-emission Climate-resilient Development Strategies

Van der Ploeg JD, Verburg PH, De Lange W (2019) The role of farmers’ intrinsic motivations in sustainable agriculture: A review. Agric Hum Values 36:1–15

Vinholis MDMB, Saes MSM, Carrer MJ, de Souza Filho HM (2021) The effect of meso-institutions on adoption of sustainable agricultural technology: A case study of the Brazilian Low Carbon Agriculture Plan. J Clean Prod 280:124334

Wang J, Fan J and Cao J (2019) System Optimization, Risk Compensation and Agricultural Land Financial Risk Control——SEM Demonstration Based on Incomplete Contract Theory. Rural Econ 2

Wang X (2019). Research on the Influencing Factors of Farmers' Pro-environmental Behavior. Zhongnan University of Economics and Law

Wang Y (2021) Research on farmers' willingness to participate in carbon trading projects and its influencing factors——Taking biogas CCER project as an example. Huazhong Agricultural University

Wiium N, Torsheim T, Wold B (2006) Normative processes and adolescents’ smoking behaviour in Norway: a multilevel analysis. Soc Sci Med 62:1810–1818

Wu Y (2021) Analysis of Cognition and Behavioral Decision-Making of Low-Carbon Utilization of Farm Households——Based on the Moderating Effect of Environmental Regulation. Huazhong Agricultural University

**ang C, Pan Q, Wang Z (2020) To reduce or not to reduce——An empirical study on farmers' weight loss and drug reduction behavior from the perspective of contradictory attitudes. Agric Technol Econ 83–92

**ong C, Wang G, Su W, Gao Q (2021) Selecting low-carbon technologies and measures for high agricultural carbon productivity in Taihu Lake Basin, China. Environ Sci Pollut Res 28:49913–49920

Yang B (2020) Research on Low-carbon Performance Evaluation and Emission Reduction Policy of Planting Industry in Shandong Province. Northeast Forestry University

Yang X (2021) Research on driving mechanism and diffusion simulation of urban residents' green purchasing behavior. China University of Mining

Yang Y, Guo Y, Luo S (2020) Consumers’ intention and cognition for low-carbon behavior: A case study of Hangzhou in China. Energies 13:5830

Yang X, Zhou X, Deng X (2022) Modeling farmers’ adoption of low-carbon agricultural technology in Jianghan Plain, China: An examination of the theory of planned behavior. Technol Forecast Soc Chang 180:121726

Yao L, Zhao M, Xu T (2016) Economic Rationality or Ecological Rationality? Research on the Behavior Logic of Farmer’s Farmland Protection. J Nan**g Agric Univ (Soc Sci Ed) 16:86–95

Yin J, Shi S (2021) Social interaction and the formation of residents′ low-carbon consumption behaviors: An embeddedness perspective. Resour Conserv Recycl 164:105116

Yue L (2021) Research on Agricultural Ecological Efficiency and Its Influencing Factors in Guizhou Province. Guizhou University of Finance and Economics

Zaleski S, Michalski R (2021) Success factors in sustainable management of IT service projects: exploratory factor analysis. Sustainability 13:4457

Zhang J, Guo D (2003) A review on the relationship between intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. Adv Psychol Sci 11:545

Zhang T, Yan T, Hu K, Zhang J (2019) Altruistic Tendency, Bounded Rationality and Farmers’ Green Agricultural Technology Adoption Behavior. J NW A&F Univ (Soc Sci Edition) 19:115–124

Zhang, K (2021) Research on Green Production Behavior of Rice Farmers from the Perspective of Industrial Organization Model. Chin Acad Agric Sci

Zhao D, Zhou H (2021) Livelihoods, Technological Constraints, and Low-Carbon Agricultural Technology Preferences of Farmers: Analytical Frameworks of Technology Adoption and Farmer Livelihoods. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18:13364

Zhao S, Duan W, Zhao D, Song Q (2022) Identifying the influence factors of residents’ low-carbon behavior under the background of “Carbon Neutrality”: An empirical study of Qingdao city, China. Energy Rep 8:6876–6886

Zhou X (2021) Research on Industry Selection and Cultivation of Small Towns in Guanzhong Area Northwest University

Zhu C (2021) Research on the aging of population in the process of China's modernization and its countermeasures. Jilin University

Funding

Research on the Livelihood Recovery of Farmers in the Loess Plateau Co** with Multiple Risks under the Coupling Effect of COVID-19 and Meteorological Disaster, National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC,2021.1.1–2024.12.31, No. 42075172), Sponsor and host Jianjun Huai. Study on the countermeasures of rapidly improving community management and service level in epidemic prevention and control, **anyang Science and Technology Bureau, Project of “Exposing the List and Being in Command,” 2022 Jan 1–2022 Dec 31, No. JBGS-005, Sponsor and host Jianjun Huai. Study on the Supporting System of Coordinated Development of Ecological Value Realization and Rural Revitalization in Typical Regions of Shaanxi Province, Shaanxi Provincial Federation of Social Sciences, 2021 Key Think Tank Research Project on Major Theoretical and Practical Problems of Philosophy and Social Sciences in Shaanxi Province, 2022.1.1–2022.12.31, No. 2021D1042, Sponsor and host Jianjun Huai.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yuling Gao: Conceptualization, data curation, investigation, modeling, formal analysis, writing original draft. Arshad Ahmad Khan: Data curation, investigation, formal analysis, review, and editing. Sufyan Ullah Khan: Software and methodology, data curation, investigation. Muhammad Abu Sufyan Ali: Data curation, investigation, review and editing. Jianjun Huai: Funding acquisition, project administration, and supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

This is an observational study, and we confirmed that no ethical approval is required.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent to publish

Not applicable.

Competing interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Responsible Editor: Zhihong Xu

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Gao, Y., Khan, A.A., Khan, S.U. et al. Investigating the rationale for low-carbon production techniques in agriculture for climate change mitigation and fostering sustainable development via achieving lowcarbon targets. Environ Sci Pollut Res (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-023-26630-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-023-26630-0