If I were a good draughtsman, I could convey an innumerable number of expressions by four strokes […] Such words as ‘pompous’ and ‘stately’ could be expressed by faces. Doing this, our descriptions would be much more flexible and various than they are expressed by adjectives.

Wittgenstein (1966). Lectures and Conversations on Aesthetics, Psychology and Religious Belief.

Abstract

Emoticons and facial emojis are ubiquitous in contemporary digital communication, where it has been proposed that they make up for the lack of social information from real faces. In this paper, I construe them as cultural artifacts that exploit the neurocognitive mechanisms for face perception. Building on a step-by-step comparison of psychological evidence on the perception of faces vis-à-vis the perception of emoticons/emojis, I assess to what extent they do effectively vicariate real faces with respect to the following four domains: (1) the expression of emotions, (2) the cultural norms for expressing emotions, (3) conveying non-affective social information, and (4) attention prioritization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Sometimes, when receiving some short text messages without much context, we are left to wonder whether they are to be taken seriously or ironically. Or maybe, whether the sender is actually “alright”, as they say, or they are resented. During a conversation, much of this kind of information is conveyed by the speaker’s face. Unfortunately, unlike words, the information usually signaled by faces cannot be conveyed in digital written communications… or can they?

Indeed, it might be argued that the communicative toolkit of many forms of digital communication encompasses some sort of ‘artificial faces’ which vicariate the lack of natural ones. I am thinking about emoticons and about a specific subset of emojis, namely, facial emojis.

The term ‘emoticon’, likely derived from a portmanteau of ‘emotion’ and ‘icon’, refers to those icons made up of punctuation which allow me, for instance, to remark my surprise as follows: :-o. While if I am expressing it with a  I am using an emoji (from the Japanese e, “image” and moji, “character”). Despite the many differences between emoticons and facial emojis, in this paper I will mainly focus on what they have in common qua stylized representations of faces. Henceforth, I will refer to them both through the abbreviation EmoT/J. Notice that EmoT/J is not to be interpreted as “Emoticons and Emojis”, but rather as “Emoticons and Facial Emojis”, as several non-facial emojis also exist (although they are used and studied less).

I am using an emoji (from the Japanese e, “image” and moji, “character”). Despite the many differences between emoticons and facial emojis, in this paper I will mainly focus on what they have in common qua stylized representations of faces. Henceforth, I will refer to them both through the abbreviation EmoT/J. Notice that EmoT/J is not to be interpreted as “Emoticons and Emojis”, but rather as “Emoticons and Facial Emojis”, as several non-facial emojis also exist (although they are used and studied less).

EmoT/J have been studied quite extensively by several academic disciplines, e.g.psychology (Cherbonnier and Michinov 2022; Bai et al. 2019), marketing (e.g. Guido et al. 2019), linguistics (e.g. Dresner and Herring 2010; Grosz et al. 2023), and semiotics (e.g. Danesi 2017; Marino 2022).

In comparison, EmoT/J have been underdiscussed in philosophy until recent years. Philosophers sometimes half-jokingly trace the dawn of emoticons to Ludwig Wittgenstein (cf. the opening quote; Krkač 2020). Plebani and Berto (2019) have also half-jokingly developed a sort of logic handbook where logic symbols are replaced by emojis, simplified graphical depictions of images like expressive faces (… and feces). In 2018, King lamented that it is “a bit surprising how little attention philosophy has given to the status of emoji” (2018, p. 1). And, I would add, to that of emoticons. Yet, in recent times the tide is changing.

Quite recently, Maier (2023) provided an in-depth semantic analysis of emojis, construing them as stylized pictures. In particular, Maier distinguishes between emojis that represent entities (e.g. cars, boats), which have truth-conditional contents (i.e., they express some state of affairs in the world), and those that represent bodily parts and gestures (including facial emojis), which have use-conditional contents (i.e., they qualify their user’s perspective toward some state of affairs).

EmoT/J seems a perfect topic for philosophers interested in situated affectivity, the thriving debate regarding how our affective lives are scaffolded by extra-bodily resources. Within the (blurry) perimeter of that debate, Lucy Osler (2020) has noted that in chat apps “text-based conversations [are often] complemented by an ever-increasing archive of emojis” (p. 584). Glazer (2017), construed emoticons as a means to express emotions in writing—unlike words, which can communicate them but in a less direct fashion (see § 3.2). And his analysis can easily apply to (some) emojis too.

However, despite the initial influence of Griffiths and Scarantino’s seminal essay on the role of emotions as tools for navigating social interactions (Griffiths and Scarantino 2009), most discussions in situated affectivity have turned their attention toward the inner, phenomenological side of emotions rather than their social role. Both Piredda’s (2020) definition of affective artifacts and Colombetti’s (2020) taxonomy of affective scaffoldingsFootnote 1 conceive and describe them primarily with respect to their influence on affective experience rather than to affective expression. Yet, since affect is not only something private we attend to by introspecting, but also an eminently social phenomenon, I propose to broaden the agenda of situated affectivity by paying attention (also) to those tools that alter the expression of affective states (Viola 2022).

With that ultimate aim in mind, in this paper I set out to reach the following intermediate step: investigating to what extent the analogy between the communicative role played by natural faces and that played by EmoT/J holds. To do so, in the next section (§ 2) I articulate the face-EmoT/J analogy and succinctly describe its theoretical underpinnings. Then, in each of the four ensuing sections (§§ 3–6) I discuss research on some facet of face perception and consider whether and to what extent the processes regarding hum an face perception might generalize to EmoT/J. More specifically, I discuss the expression of emotions (§ 3), the cultural norms that regulate or modulate them (§ 4), non-affective social information (§ 5), and the prioritized attention toward face-like visual stimuli (§ 6). In the conclusive section I wrap up and suggest further investigations (§ 7).

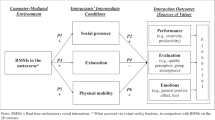

2 Theoretical Background: EmoT/J as Cultural Analogues of Natural Faces

The psychologist Van Kleef (2017) has suggested that “expressions of the same emotion that are emitted via different expressive modalities ([including] emoticons) have comparable effects, provided that the emotional expressions can be perceived by others” (p. 213). This analogy has been vindicated by empirical evidence (Van Kleef et al. 2015; Erle et al. 2022), albeit some important discrepancies also exist between what real faces and EmoT/J can convey (see below). Yet, I think that the analogy runs both broader and deeper than van Kleef’s original formulation suggests.

Why broader? To put it simply, because just as the role of faces in social cognition transcends the mere expression of emotions, so EmoT/J also play other roles in social cognition besides conveying affective states (see §§ 5–6).

Why deeper? Because an interesting story must be told, I submit, on how culture has exploited some of our neurobiological endowment. To tell this story, Sperber and Hirschfeld’s (2007) distinction between a proper domain and an actual domain of cognitive capacities can come in handyFootnote 2. The proper domain indicates what a psychological capacity has evolved for, its teleological raison d’ être. An example they describe—and that is also relevant for our present purpose—is the cognitive capacity for face detection, which probably developed in order to spot the face of a conspecific or predator, and to steer our attention towards it. To operate efficiently, cognitive capacities often leverage on some shortcuts. For instance, face detection can be activated also by simple visual patterns resembling a T or an inverted triangle, as in the logic symbol “∵” (see § 6). The mismatch between the actual and the proper domains of a capacity might result in either false negatives or false positives. For instance, we have a hard time spotting a face when eyes and nose do not conform to the aforementioned pattern. More often, given that the mechanism for face detection seems biased toward false positives, we can be misled into seeing faces when there are none—a phenomenon known as facial pareidolia. Interestingly, when the activation of a capacity admits degrees, activating conditions outside its proper domain may elicit the capacity even more intensely than proper conditions. A textbook case dates back to the pioneer of ethology Niko Tinbergen. He reported that some Herring Gull chicks, which typically peck on their parents’ red bills to request food (proper domain), peck more intensely when confronted with some artificial red stimuli. He thus coined the term superstimuli to refer to the class of objects that activate a capacity even more than it was intended to be activated (Tinbergen and Perdeck 1950).

Sperber & Hirschfeld suggest that cultural artifacts may be produced by deliberately reproducing conditions that tap into some capacity’s actual domain, irrespectively of their proper domains. For example, they claim, masks and portraits exploit the mechanism for human face perception, because they exhibit some formal condition that activates its actual domain, despite not falling into its proper domain (real faces).

I claim that, similarly to masks (on which see Viola 2023), EmoT/J are a particular class of artifacts that exploits the (neurotypical) human mechanisms for face perception to convey social information typically conveyed by real human faces (or, at least, that we extract from real faces; cf. § 5)Footnote 3. Psychological research has shown that human faces provide different kinds of social information, whose processing is due to partially distinct neurocognitive mechanisms. Accordingly, the architecture of the next four sections will carve out several aspects of face perception along the joints of these relatively separated mechanisms.

3 Expressing Emotions

3.1 Facial Expressions of Emotions

The intimate connection between facial movements and emotions has been vastly debated in psychologyFootnote 4. Even before Darwin published his influential book The Expression of Emotion in Man and Animals (Darwin 1872), the link between emotions and facial movements had already been discussed by some of his sources, like Charles Bell or Duchenne de Boulogne. The ‘golden age’ of research on facial expressions of emotions was probably around the 1970s due to the research program envisaged by Silvan Tomkins and pursued by Paul Ekman and Carroll Izard. For them, the onset of an emotion inescapably triggers a specific and innate set of facial movements common to all humankind, which they dubbed facial affect program (Ekman and Friesen 1969). The expression-emotion map** hence became the cornerstone of a research agenda that thrived in spite of a hoard of counterevidence and criticisms. Contemporary reappraisals suggest that this universal emotion-expression link might be way more modest than initially predicted (Barrett et al. 2019). The debate is open and heated, but recent empirical and theoretical work suggests that facial expressions of emotion do have some universal and spontaneous core, albeit one that leaves room for ‘accents’ and ‘dialects’ (Elfenbein 2013) and other culturally- and context-driven modulations (Cowen et al. 2021; Jack et al. 2012, 2016; Glazer 2019, 2022; see below, § 4).

On the conceptual level, one of the most radical opponents of the expression-emotion link is probably Alan Fridlund. He rejects the link between facial displays and emotions outright, regarding these as invisible and ineffable entities from the scientific point of view. Instead, he proposes to interpret facial movements in terms of some communicative intention: for instance, instead of ‘happiness’, a smile ought to be interpreted as an attempt to influence the observer to play or to affiliate (Crivelli and Fridlund 2018). While his criticism has the merit of highlighting the appeal to the teleological, strategical notion of facial movements, Scarantino (2017) convincingly shows that we neither need nor should give up on the interpretation of facial expressions in terms of emotions, as the expressive and the teleological facets can go (and often do go) hand-in-hand (see also Van Kleef 2009). Scarantino also points out that emotions can be expressed either via spontaneous movements or via intentional (and potentially deceiving) movements (Scarantino 2019). Most probably, however, the relationship between spontaneous and intentional emotional displays is better construed as a continuum than as a strict dichotomy.

That being said, while these two components are entrenched, some facial movements play certain pragmatic roles that cannot be sensibly couched in terms of emotion. Their discussion is postponed to § 5.

Some lines of evidence inspired by embodied cognition suggest that facial expressions can actually trigger certain affective reactions both in the expressor and the observer. According to the facial feedback hypothesis, observing mouth movements that resemble either a smile or a frowny mouth may induce positive or negative feelings, respectively. After several replications yielding mixed results, a recent massive multi-lab experiment (Coles et al. 2022) has robustly established that this effect occurs… although it is very slight. Unlike ‘cold’ ways to convey emotions, facial expressions have been claimed to induce emotional mimicry and emotional contagion (i.e. they can prompt the observer to mimic the emoter’s expression, and possibly even their emotion), thus promoting bonding and empathy between the expressor and the observers. This mechanism seems to be shared by several primates (Palagi et al. 2020), although in humans it is modulated by several social and contextual variables (Fischer and Hess 2017).

3.2 EmoT/J as Expressions of Emotions

The first and most obvious function of EmoT/J is that of expressing some affective state whose facial display they represent in a stylized fashion (Dresner and Herring 2010; Glazer 2017; Maier 2023: § 5). This EmoT/J- mediated emotional expression can occur alone, or it can accompany some text.

We can express our approbation or scorn about something by means of three typographical signs, as in the emoticons :-) or :-/, or via the corresponding emojis, as in  or

or  .

.

The emotion expressive role of EmoT/J has been vindicated by a solid amount of psychological literature (for reviews, Bai et al. 2019; Cherbonnier and Michinov 2022). Let us examine a few studies. In a recent online experiment on 217 participants from several countries, Neel and collaborators (2023) showed that the same affectively neutral text message (e.g. “It’s on Wednesday”) tends to be interpreted as more positively valenced when accompanied by a positive emoji (a slightly smiling face; avg valence 7.70 on a scale from 1 to 10, SD 1.67) than with a neutral emoji (a couple of eyes; avg 5.53, SD 1.56) or no emoji at all (5.10, SD 1.26), and more negatively with a negative emoji (a slightly frowning face; 3.25, SD 1.48).

The analogy between perceiving emotional emojis and emotional faces is further corroborated by an EEG study by Gantiva et al. (2020). 30 participants observed similar electrophysiological activity when subjects perceived angry, neutral and happy emojis or pictures of facial expressions of emotions from a database. However, the authors also report that the magnitude of some electrocortical activity patterns arguably reflecting salience and motivational force, namely P100 and LPP, were higher for faces than for emojis.

Does this expressive power generalize from emojis to emoticons? Yes, although probably to a lesser extent. An experiment on 127 subjects (Ganster et al. 2012) also employed neutral texts (albeit in the context of a longer chat) to compare the valence-altering effects of character strings (i.e. emoticons) and pictograms (similar to emojis). They found that both categories of stimuli enhance or decrease the emotional valence of a message, but the effect of emoji-like pictograms is bigger.

A similar trend is also observed in a study by Fischer and Herbert (2021). Their subjects (83 valid) were shown emojis, emoticons and pictures of facial expressions of emotions, and were asked to provide ratings of arousal (activated-sleepy), valence (pleasure-displeasure) and ‘emotionality’ (how well a given stimulus represents the emotion it is meant to represent). For all three dimensions, the ratings received by emojis were similar to those received by faces. Both were higher than those received by emoticons.

Some evidence even suggests that, in some circumstances, emojis could work as superstimuli when it comes to conveying emotions, namely, they convey certain emotions better than the corresponding expressions on real faces. For instance, a recent study on the recognition of Ekman’s 6 basic emotionsFootnote 5 from facial expressions and emojis performed on 96 male and female university students showed that male participants are better at recognizing emojis than female ones; and that males’ accuracy is higher with emojis than with actual faces (Dalle Nogare et al. 2023). According to the authors, this may be due to the fact that males tend to use emojis more than females.

In another study, Cherbonnier and Michinov (2021) designed and validated ‘superstimuli’ emojis, i.e. a set of emojis that represent ‘the basic six’ better than both facial counterparts and other emojis setsFootnote 6—where ‘better’ means “associated with the target emotion with higher accuracy”.

The evidence discussed thus far—not to mention the dozen studies I could not discuss for the sake of length—provides strong support for the intuitive idea that EmoT/J seem perfectly capable of conveying emotional states. Of course, EmoT/J must be conceived as analogous to intentional displays rather than spontaneous ones—and as such, they are more open to deception. Unlike spontaneous facial movements during in face-to-face interactions, sending a (message containing an) EmoT/J often requires a deliberative action, such as pressing “send”. In theory, that might give the sender enough time to reconsider and edit the message, potentially for the sake of strategic interactions—including deceiving ones. In practice, many digital interactions are also rather spontaneous: after all, people may often send chat messages impulsively only to regret them a minute later.Footnote 7

We may want to distinguish between two ways of ‘conveying’ emotion—say, a ‘cold’ way and a ‘hot’ one. Unlike an emotion word like “sadness”, which can refer to sadness without manifesting it (but see Glazer 2017; 2023), a facial expression seems capable of doing something more: at least in some cases (as in spontaneous expressions), it conveys emotions with vivid affective force, reflecting the emoter’s own state and possibly altering the observers’ affective states. So, are EmoT/J capable of conveying emotions in the ‘hot’ way, similarly to facial expressions, or are they only confined to the ‘cold’ way, just like emotion words?Footnote 8 Indeed, the literature presents some evidence for a ‘hot’ status of EmoT/J. In a large study, Lohmann and collaborators (2017) showed the same text message to 1745 female participants, accompanied by either a positive or a negative emoji, and asked them to imagine that it had been received from a dear friend. Other than promoting the ascription of a positive or negative state to the imaginary friend, emojis also produced congruent effects on the subjects’ mood, which Lohmann and collaborators interpreted in terms of elicited emotional contagion.

Arguments in favor of the ‘hot’ and affectively efficacious nature of emojis can also be found in a study on 100 subjects by Gantiva et al. (2021), who reported that emojis effectively altered several physiological parameters within the observers: the activity of the facial muscles regulating smiling and frowning, skin conductance (reflecting sweat), heart rate. These modifications were comparable to those induced by facial expressions of the same emotion. For instance, both happy faces and happy emojis induced activation of the zygomaticus major, the muscle that raises lips during smiles, suggesting that emojis may successfully trigger facial mimicry. Moreover, an EEG study by Liao and colleagues (2021) showed similar electrophysiological and self-reported responses to pain when expressed by faces and emojis, although the pain was perceived as more intense in faces than in emojis, both in self reports and in neural data.

There is, however, an important limitation to EmoT/J’s ability to scaffold bonding via emotional mimicry. A pivotal ingredient of mimicry-based bonding is pupil mimicry (Prochazkova et al. 2018). To put it simply, when someone’s pupil diameter co-varies with mine while we interact, I am more likely to trust them. Yet, as EmoT/J have fixed pupil size, their potential for emotional mimicry is largely limited—although it would be intriguing to check, for example, whether similar EmoT/J with dilated or narrow pupils (e.g. °_° vs. O_O) could be perceived differently by an observer based on their own pupil size while observing it.

For those who accept some degree of constructionism in emotion theory, i.e. for those who think that emotions are constituted by means of some conceptual act based on raw affective ingredients such as undifferentiated arousal (e.g. Schachter and Singer 1962; Russell 2003; Barrett 2017), EmoT/J can also help shape the sender’s own affect. By ty** :-), the sender is endorsing an interpretation of their own affective states along the ‘plot’ of happiness, and manifesting it not only to the receiver, but also to themselves. In sum, it seems reasonable to conceive EmoT/J as a sort of ‘affective attractor’ which allows the receiver and the sender to synchronize on some affective state.

4 Cultural Norms

4.1 Cultural Norms and Emotions

While the tension between natural/innate and cultural/learnt is a cliché of most psychological topics, it rarely manifests itself as intensely as in the debate over the facial expression of emotions. Even a herald of innatism in emotion like Ekman conceded that culture plays a role in facial expression—after all, he dubbed his own theory neurocultural (Ekman and Friesen 1969). In fact, while the functioning of the facial affect programs in themselves is pretty rigid, Ekman granted culture and learning a modulating role both upstream and downstream. Upstream, cultural and idiosyncratic factors may alter the conditions elicited by the facial affect programs (e.g., eating bugs may be disgusting in some cultures but not in others). Downstream, the so-called display rules regulate the appropriateness of displaying certain emotions in given contexts, often nudging the emoter to inhibit, alter, or artificially display an emotional expression that suits the moment (e.g., in most Western countries you are not supposed to laugh at a funeral).

Display rules, albeit often with different labels, have been studied by several historians and sociologists of emotion (e.g. Hoschild 1983; Stearns and Stearns 1985). In particular, Hoschild’s notion of emotional labor, i.e. the idea that some jobs (typically those performed by women) impose strict rules upon which emotions to express (and perhaps even to feel), germinated in a rich strand of studies about the social expectation that negative emotions get suppressed and positive ones (over)expressed in the workplace—possibly resulting in emotional dissonance and other forms of distress that place a burden on the workers’ well-being (Zapf 2002).

As compared to Ekman, many contemporary experimental psychologists are more inclined to ascribe a larger role to the cultural modulation of facial expression (see for instance Jack et al. 2012, 2016; Elfenbein 2013; Cowen and Keltner 2021). These modulations interest both the expressor and the observer. For instance, Jack and collaborators (2012) highlighted that in Eastern Asia the eye region is more diagnostic for many emotions than in Western countries, whose inhabitants rely more heavily on the mouth. As Glazer (2022) points out, a moderately universalistic stance on the expression of emotion leaves room for cultural modulators. For instance, as mentioned above, cultural norms may dictate whether to amplify or demote a particular facial muscular movement in order to endorse or suppress emotional communication in the presence of a specific audience (see Matsumoto et al. 2008). But they can also have a role in fine-tuning the facial movements prompted by some innate facial affect program-like mechanisms, or teaching an observer where to stare to recognize an emotion (take a stroll amidst the bookshelves dedicated to preschoolers: you will find a plethora of books aiming to teach kids how to identify, regulate and express their emotions; cf. Widen and Russell 2010).

4.2 Cultural Norms and EmoT/J

Since social norms modulate how and when emotions are expressed via facial movements, it should not surprise that some researchers have undertaken investigations concerning the norms that can be at play in EmoT/J-mediated expressions.

The available evidence seems rather in line with this hypothesis. In one of the first studies of this kind, Derks and colleagues (2007) asked 158 secondary school students from Netherlands to respond to internet chats regarding task-oriented and socio-emotional contexts (working on a class assignment and choosing a present for a common friend, respectively). Subjects could respond with text or emojisFootnote 9, or with a combination thereof. The results showed that “people use more emoticons [sic] in socio-emotional contexts than in task-oriented contexts” (Derks et al. 2007, p. 846) leading the authors to conclude that “display rules for Internet communication are comparable to display rules for face-to-face communication” (ibid.).

More recently, Liu (2023) has reported a nuanced set of display rules based on a large sample of young Japanese participants (age 12–29, N = 1289, only 78 males). As in the study by Derks and colleagues (2007), subjects had to provide answers to some chat messages with or without emojis, but they were allowed a larger set of emojis to pick from in order to best represent real-life contexts. The chats differed in several social variables, e.g. the interactor was unfamiliar or familiar, a friend of the same or of the opposite sex, of higher or equal social status, in a private or in a public context. The results show that “participants [express] most emotions toward same-sex friends, followed by opposite-sex friends, unfamiliar individuals, and those of high status” (Liu 2023, p. 12). Moreover, different emojis were typically employed for each context. Another interesting observation is that “smiling emojis were used when participants de-intensified their expression of negative emotions” (p. 13).

However, some studies warn us that the rules regulating facial movements and EmoT/J usage are not perfectly parallel. Somewhat ironically, one of those was performed by a team led by the scholar who explicitly proposed the face-EmoT/J analogy, Van Kleef. In three experiments, he and his team asked their participants to assign warmth and competence ratings to some text messages. The same texts were compared either with or without ‘smileys’, i.e. a rather stylized smiling emoticon—as well as to neutral and smiling face photos used as control conditions. It was found that “contrary to actual smiles, smileys do not increase perceptions of warmth and actually reduce perceptions of competence” (Glikson et al. 2018), but only in formal settings.

Yet, cultural influences on EmoT/J may go beyond display rules dictating when to use which EmoT/J. As for cultural dialect and accents in facial expressions, they may also bring about slight modifications in EmoT/J shape and meaning.

For instance, on noting how in Western countries the expression and recognition of facial expressions is more mouth-driven than in Eastern Asia, Jack and collaborators (2012) trace a parallel with the corresponding emoticons, remarking that often “In Eastern Asia, (^.^) is happy and (>.<) is angry” (p. 7242). Their suggestion opens up an intriguing but under-investigated research hypothesis, namely that EmoT/J may contribute to sha** our facial expressions of emotions, as well as our gazing patterns when looking at someone else’s facial expressions. A simple prediction could be that Western subjects exposed to a huge amount of East Asian, eye-centered emoticons would increase their ocular movements at the expense of mouth movements when expressing emotions, and/or take the eye region to be more diagnostic for reading emotions from an expressing face.

5 Non-affective Information

5.1 Non-affective Information from the Face

As already hinted, not all the social information an observer can retrieve from a face pertains to the affective domain. First and most obviously, faces allow for the recognition of one’s identity. From a neurocognitive point of view, this process of recognizing the identity of a familiar person is thought to be largely independent of that of emotion recognition (Bruce and Young 1986): the former is mainly based on invariant features of the face and hinges upon neural machinery going from the occipital to the temporal cortex, while the latter is based on facial movements and hinges upon the workings of an occipito-parietal neural pathway (Haxby et al. 2000). Of course, we cannot recognize the personal identity of someone we have never met. However, the first time we see someone we tend to form some heuristic judgment about their social identity. For instance, a rapid gaze often suffices to infer someone’s age and biological sex with some accuracy. But since our information-hungry brains are prone to fill gaps in knowledge of the social world by making bold generalizations, we often form first impressions of someone’s personality based on their facial appearance. Such impressions are often ill-founded, and yet they exert a worryingly sizable influence on our attitudes toward strangers (Todorov et al. 2015; Smortchkova 2022).

Besides the information we draw from a still face, some facial movements also exist that play several communicative functions not pertaining to the emotional domain. Many such movements—sometimes construed as gestures—often complement verbal communication, playing a relevant pragmatic role. An obvious example are facial movements for nodding or denying. Moreover, gaze may have multiple functions in social interactions, such as engaging in (or disengaging from) interaction when we move our gaze upon (or away from) an interactor’s eyes; or regulating turn-taking (for a review, see Rossano 2013). Domaneschi and colleagues (2017) have shown that pictures of the upper region of certain facial expressions suffice to alter the illocutionary force of some sentences: depending on different contractions of the muscles surrounding the eye regions (eyebrows, eyelids, and cheeks), the same sentence is perceived by the subject as belonging to a different illocutionary type, such as an assertion, an order, or advice, among others.

5.2 Non-affective Information from EmoT/J

While emoticons have been invented multiple timesFootnote 10, the most famous inventor of the smiley face is probably the scientist Scott E. Fahlman. On September 19,1982, he made the following proposal on Usenet—a discussion board at the Carnegie Mellon University, a sort of precursor of internet forums, seemingly loaded with irony:

I propose that the following character sequence for joke markers:

:-)

Read it sideways. Actually, it is probably more economical to mark.

things that are NOT jokes, given current trends. For this, use.

:-(.

(Fahlman 1982)

Despite being partly (meta-)ironical in itself, Fahlman’s proposal also anticipates something that linguists will later concede about emoticons (e.g. Dresner and Herring 2010), and subsequently about emojis (e.g. Gawne and McCulloch 2019), namely, that they can play some pragmatic functions. For instance, Dresner and Herring (2010, p. 256) interpret the winking face emoticon—i.e. ;-)—as “an indicator that the writer is joking, teasing, or otherwise not serious about the message’s propositional content”, immediately clarifying that “joking is not an emotion—one could joke while being in a variety of distinct affective states. Rather, joking is a type of illocutionary force, something that we do by what we say” (ibid.). Similarly, smiling faces may be used, among other things, to smooth down the illocutionary force of some speech acts – e.g. downgrading an order into a piece of advice. In that respect, their working seems comparable to that of (the upper region of) faces in Domaneschi et al.’s experiment (2017).

As soon as we shift the focus of our analysis from the representation of facial movements to the representation of still facial features, the face-EmoT/J analogy reveals its greatest shortcomings. It goes without saying that, unlike actual faces, EmoT/J cannot be used to infer personal identity. In fact, in virtue of their stylization (Maier 2023), EmoT/J are meant to represent anyone’s face in general, but no face in particularFootnote 11.

Neither can they provide clues for social identity, if not indirectly. It is certainly possible to make accurate inferences about someone’s personality traits based on how they use emojis in digital communication (especially extraversion and openness; see Wall et al. 2016). Yet, unlike actual faces, EmoT/J provide no clues about the socio-demographic factors of their users. This is not to say that emojis (both facial and non-facial) cannot encode some demographic factors: for instance, they can encode ethnicity via skin color, or old/young age. Yet, the way in which using an emoji of a certain skin color represents ethnicity entails a different sense of representation than actually belonging to some ethnic group: the latter is a natural and non-intentional representation, while the former is a deliberate and iconic representation, which is freely available to users irrespective of their own skin colors. In fact, many white-skinned Twitter users have used dark-skinned emojis to express their endorsement to the Black Lives Matter movement (Alfano et al. 2022).

6 Face Detection: Increasing Salience and Activating Theory of Mind

6.1 Detecting Actual Faces

While a lot of social information can be inferred from faces (correctly or not), the very first bit of information that a natural face provides is that there is a face, and hence an agent. The mechanism for detecting faces is prone to false positives: it gets automatically and mandatorily triggered by whatever stimulus exhibits a face-like gestalt, i.e., whatever visual pattern resembles a T or an inverted triangle (∵). Once detected, faces are quick to grab our attention (i.e., they get rapidly foveated) and slow to let it go (Palermo and Rhodes 2007; Langton et al. 2008; Devue et al. 2012).

Face detection is also deeply inscribed in our ontogeny: experiments on human newborns show that they preferentially pay attention to face-like patterns (∵), as compared to an upside-down-face-like pattern (∴) or to randomly scrambled dots (Goren et al. 1975; Buiatti et al. 2019). Impressively, by projecting face-like dots on the uterine wall of pregnant mothers thanks to ultrasound, Reid and collaborators (2017) observed a similar preference even in fetuses at the third trimester, revealed by fetuses’ head movements toward the face-like stimuli.

Once our face detection mechanism locks onto something—be it an actual face or a pareidolia (see Alais et al. 2021)—it ignites a cascade of inferences to extract social information from it, including all the mechanisms described in the previous section of this paper. In a slogan, we can say that face detection triggers theory of mind or person perception. When we see a face (or face-like visual pattern), we cannot even decide not to recognize its identity or emotional expression, or not to form any impressions about its bearer. In fact, once we see a face, it takes less than 100 milliseconds to decode a lot of social information and to formulate a hoard of first impressions about it (Todorov et al. 2015).

6.2 Detecting EmoT/J

Despite clearly falling outside the proper domain of face detection, most EmoT/J fall within its actual domainFootnote 12. As such, they may benefit from the privileged ‘attention-grabbing’ status of face-detection-triggering stimuli. While most studies in experimental psychology refer to facial pareidolias in general (usually employing accidental paraidolias as stimuli), with due prudence their results may be generalized to EmoT/J too.

Besides the studies on abstract face-like patterns (∵) mentioned in the previous sub-section about infants (Goren et al. 1975; Buiatti et al. 2019) and highly developed fetuses (Reid et al. 2017), more recent investigations attest the effects of more ecological pareidolias in adults. For instance, in two experiments on Australian students (N = 18 for each experiment), Keys and collaborators (2021) demonstrated that pictures of inanimate objects resembling faces are located more rapidly than similar ‘face-less’ objects in visual search tasks.

More recently, Jakobsen and collaborators (2023) performed a series of experiments using the probe-dot task, a paradigm where subjects are briefly exposed to a pair of images (cues) both to the right and to the left of the center of the screen, and then to a target image (probe) appearing either on the right or on the left. Subjects have to indicate the side of the target probe as fast and accurately as possible. When used as cues in a congruent location, pareidolic images facilitated faster and more accurate recognition of the probe (unless they were presented upside-down), probably because they drew subjects’ attention in that direction.

Caruana and Seymour (2022) provide further evidence that face-like objects grab attention, as they reach perceptual awareness more easily than corresponding non-face-like ones. They showed pictures of several face-like and face-less objects to 41 subjects, masking them with breaking continuous flash suppression,Footnote 13 and reported that face-like stimuli reached awareness more often than non-facial stimuli.

Interestingly, in two EEG experiments where subjects (N = 17 and N = 22, respectively) were shown both actual faces and pareidolic face-like objects amidst several other images shifting at high frequencies, Rekow and colleagues (2022) described similar electrophysiological patterns for subjects who reported awareness of either faces or pareidolias, supporting the similarity of both kinds of stimuli from a neural point of view.

Some research on marketing and advertising also corroborates the power of (accidental) pareidolic stimuli to attract consumers’ attention (e.g. Guido et al. 2019; Noble et al. 2023). In the field of marketing research, Valenzuela-Gálvez and others (2023) report higher customer engagement in emails containing emojis—although, somehow surprisingly, non-face emojis were even more efficient than face emojis in the context of their experiments.

All things considered, despite being barely mentioned in theoretical reviews about the roles of EmoT/J (but see Gawne and McCulloch 2019) and possibly underappreciated by EmoT/J users themselves, it seems that exploiting the attention-prioritizing powers of face detection could be reasonably listed among the powers of EmoT/J.

7 Conclusion and Caveats

The aim of this paper was to investigate whether the empirical literature vindicates the status of emoticons and facial emojis—in short, EmoT/J—as cultural artifacts that vicariate our natural faces, allowing us to convey emotions and other facial information. Like other cultural artifacts, EmoT/J exploit a misalignment between the proper domain of certain psychological capacities (the thing they were teleologically selected to do) and their actual domain (the way in which they actually work). In particular, they exploit the fact that face perception seems to operate on some non-facial stimuli to convey some of the social information typically conveyed by actual faces. Hence, I have offered a philosophical reading of the empirical evidence regarding the analogy between actual faces and EmoT/J, highlighting where it pertains and where it does not, with respect to the following aspects of face perception: the expression of emotions, the cultural norms that surround it, non-affective social information, and attention prioritization. In many respects, EmoT/J seem to be up to their task of constituting “face avatars”—though not without some “buts”. Indeed, they seem capable of expressing emotion, and even eliciting emotional contagion; but they can never be spontaneous like some facial expressions, and as a result they cannot be as reliable. They also seem influenced by cultural norms about when to express emotion, and even about how to express it; yet, the appropriate contexts for smiles do not perfectly match those for smileys. They substitute faces for some non-affective pragmatic roles like setting the illocutionary force of some speech act; but they are silent about most of the social information one could infer from faces. And finally, similar to actual faces, they are attention-grabbing.

I do not claim this discussion to be exhaustive. For instance, I have not discussed the possibility that EmoT/J may undertake complex semantical roles. The project Emoji Dick, for example, a translation of Melville’s Moby Dick made up only of emojis (https://www.emojidick.com/), seems to suggest that they may have the resources to replace written language, at least in some cases. However, it is doubtful that emoji-only texts possess the grammatical richness that allows for complex sentences (see Cohn et al. 2019). And in any case, it is highly likely that richer semantics pertains to non-facial emojis (Maier 2023), which remain outside the scope of the present discussion.

Yet, much more should be said even within the broad categories of the face perception processes I have identified. For instance, Palmer and Clifford (2020) have showed that not only do pareidolic face-like objects attract our gazes toward them: they may also steer our gaze toward the direction in which they are looking, just like natural faces. Shall we conclude that emojis with sufficiently detailed gaze direction can steer our gaze where they want?

Perhaps it is too early to ‘conclude’ anything. In fact, rather than concluding anything, this paper is aimed at inspiring new empirical studies. But it also aims, echoing King (2018), to invite further philosophical reflections about EmoT/J. The ability to free our oral language from the spatiotemporal constraints of the “here and now” by means of writing has changed our societies (Ong 1982) and our brains (Dehaene 2009) forever. Now that the same power has been endowed to our faces, where to next?

Notes

The label ‘artifact’ is usually reserved to objects that have undergone some act of creation or modification that makes them suited for a given function (Hilpinen 1992). To also include objects that have not undergone such a transformation, one should rather speak of scaffoldings (as in Colombetti 2020). EmoT/J being human-made objects, we can sidestep this worry since they fully qualify as artifacts.

Sperber & Hirschfeld’s (2007) distinction between proper and actual domains was originally framed in terms of domains of a cognitive module, as they embraced the massive modularity hypothesis. However, while using the distinction I am obviously assuming some degree of domain specificity in the psychological mechanisms for face perception, I prefer to use the theoretically uncommitted term ‘capacity’ rather than the theoretically-laden notion of module, which is today controversial (see Zerilli 2019). This is also because face perception is a complex capacity involving many partially independent mechanisms, each one yielding a partially distinct output.

This idea was partially inspired by the ethologist and neuroscientist Giorgio Vallortigara, who compared EmoT/J to superstimuli both in a scientific paper (Buiatti et al. 2019, p. 4628) and in popular science interviews. However, while some EmoT/J may act as superstimuli, i.e. they activate face perception processes more than do actual faces, this hardly applies to the whole category of EmoT/J.

While most scholars acknowledge that an intimate relationship exists between facial movements and emotions (but see Crivelli and Fridlund 2018), the exact nature of this relationship is a matter of debate among philosophers. In fact, while facial (and bodily) movements are often taken as ‘by-products’ of some emotion, advocates of some theory of direct social perception (e.g. Newen et al. 2015) hold that expressive behaviors (e.g. crying) are proper parts of emotions (e.g. sadness). As such, it is literally possible to see someone’s sadness (the whole) when we see them crying (a part), just like we literally see a tridimensional object although we necessarily see only a side of it (but see Glazer 2018; cf. fn. 8 below).

Anger, Disgust, Fear, Happiness, Sadness, Surprise.

This is nicely attested by the very existence of apps like On a second thought, a “delay/recall platform for mobile and desktop applications” which enables “customers control over their messages and peer-to-peer payments, allowing them to “undo” mistakes before they get to the other person” https://www.onsecondthought.co/.

If we accept a view on emotion according to which we can directly perceive emotions via their manifestations because expressive behaviors are proper parts of emotions (e.g. Newen et al. 2015; cf. fn. 4 above), does it follow that we might see someone’s happiness via a smiley or some other EmoT/J? While this question requires extensive philosophical arguments that cannot be fleshed out in this paper, I suggest that a necessary (but not sufficient) condition for EmoT/J to be considered as proper (expressive) parts of emotions is that they are capable of conveying emotions in the ‘hot’ way.

Derks et al. (2007) speak of emoticons, but the list of six emoticons they denote includes highly graphical elements, e.g. a devil “emoticon”, suggesting that they are referring to pictograms, which are commonly called emojis. Similar terminological mix-ups are not infrequent, especially in the early years of emojis, when the terminology still had to be consolidated.

See for instance Krkač (2020); Marino (2022).

Could it be the case that, in particular circumstances, some EmoT/J could be redeployed to refer to someone in particular? Consider a chat of friends where only Paul wears eyeglasses. Someone asks “remind me, who is preparing dinner this evening?” and someone else replies with an emoji with eyeglasses to refer to Paul. However, due to their limited scope, such cases do not seem to pose a worrisome counterexample for the claim that EmoT/J normally aim to express universal facial features. Moreover, the inclusion of eyeglasses suggests that the eyeglass emoji might not be a purely facial emoji, but more likely a hybrid facial/non-facial emoji, the latter category being more apt to play a semantic role like referring (Maier 2023).

I say “many EmoT/J” because horizontal ones, such as the emoticons :-) or XD, may fall outside the actual domain of the face detection mechanism, or at least count as borderline cases. Similar to identity recognition, which is knowingly impaired when faces are perceived in atypical orientations (e.g. upside-down faces; see Yin 1969), the attention allocation effect of the face detection mechanism seems diminished when stimuli are presented in an atypical orientation (Olk and Garay-Vado 2011; Jakobsen et al. 2023, exp2).

Breaking continuous flash suppression is a technique for exposing subjects to visual stimuli that usually do not reach awareness. Subjects are shown different visual stimuli for the two eyes: the target stimulus gradually appears and disappears in the non-dominant eye, while the dominant eye is presented with a distractor, usually a colorful pattern.

References

Alais D, Xu Y, Wardle SG, Taubert J (2021) A shared mechanism for facial expression in human faces and face pareidolia. Proc Royal Soc B 288(1954):20210966

Alfano M, Reimann R, Quintana IO, Chan A, Cheong M, Klein C (2022) The affiliative use of emoji and hashtags in the black lives matter movement in twitter. Social Sci Comput Rev. https://doi.org/10.1177/08944393221131928

Bai Q, Dan Q, Mu Z, Yang M (2019) A systematic review of emoji: current research and future perspectives. Front Psychol 10:2221

Barrett LF (2017) The theory of constructed emotion: an active inference account of interoception and categorization. Soc Cognit Affect Neurosci 12(1):1–23

Barrett LF, Adolphs R, Marsella S, Martinez AM, Pollak SD (2019) Emotional expressions reconsidered: Challenges to inferring emotion from human facial movements. Psychol Scie Public Interest 20(1):1–68

Bruce V, Young A (1986) Understanding face recognition. Br J Psychol 77(3):305–327

Buiatti M, Di Giorgio E, Piazza M, Polloni C, Menna G, Taddei F, Vallortigara G (2019) Cortical route for facelike pattern processing in human newborns. Proc Natl Acad Sci 116(10):4625–4630

Caruana N, Seymour K (2022) Objects that induce face pareidolia are prioritized by the visual system. Br J Psychol 113(2):496–507

Cherbonnier A, Michinov N (2021) The recognition of emotions beyond facial expressions: comparing emoticons specifically designed to convey basic emotions with other modes of expression. Comput Hum Behav 118:106689

Cherbonnier A, Michinov N (2022) The Recognition of emotions conveyed by Emoticons and emojis: a systematic literature review. Technol Mind Behav, 3(2)

Cohn N, Engelen J, Schilperoord J (2019) The grammar of emoji? Constraints on communicative pictorial sequencing. Cogn Res Princ Implic 4:1–18

Coles NA, March DS, Marmolejo-Ramos F, Larsen JT, Arinze NC, Ndukaihe IL, Liuzza MT (2022) A multi-lab test of the facial feedback hypothesis by the many smiles collaboration. Nat Hum Behav 6(12):1731–1742

Colombetti G (2020) Emoting the situated mind: a taxonomy of affective material scaffolds. JOLMA. J Philos Lang Mind Arts 1(2):215–236

Cowen AS, Keltner D (2021) Semantic space theory: a computational approach to emotion. Trends Cogn Sci 25(2):124–136

Cowen AS, Keltner D, Schroff F, Jou B, Adam H, Prasad G (2021) Sixteen facial expressions occur in similar contexts worldwide. Nature 589(7841):251–257

Crivelli C, Fridlund AJ (2018) Facial displays are tools for social influence. Trends Cogn Sci 22(5):388–399

Danesi M (2017) The semiotics of emoji: the rise of visual language in the age of the Internet. Bloomsbury, London Oxford, New York, Sydney, Delhi

Dalle Nogare L, Cerri A, Proverbio AM (2023) Emojis are comprehended better than facial expressions, by male participants. Behavioral Sci 13(3):278

Dehaene S (2009) Reading in the brain: the science and evolution of a human invention. Viking, New York

Derks D, Bos AE, Von Grumbkow J (2007) Emoticons and social interaction on the internet: the importance of social context. Comput Hum Behav 23(1):842–849

Devue C, Belopolsky AV, Theeuwes J (2012) Oculomotor guidance and capture by irrelevant faces. PLoS One 7(4):e34598

Domaneschi F, Passarelli M, Chiorri C (2017) Facial expressions and speech acts: experimental evidences on the role of the upper face as an illocutionary force indicating device in language comprehension. Cog Process 18:285–306

Dresner E, Herring SC (2010) Functions of the nonverbal in CMC: emoticons and illocutionary force. Commun Theory 20(3):249–268

Ekman P, Friesen WV (1969) The repertoire of nonverbal behavior: categories, origins, usage, and coding. Semiotica 1(1):49–98

Elfenbein HA (2013) Nonverbal dialects and accents in facial expressions of emotion. Emot Rev 5(1):90–96

Erle TM, Schmid K, Goslar SH, Martin JD (2022) Emojis as social information in digital communication. Emotion 22(7):1529

Fahlman SE (1982) Original bboard thread in which:-) was proposed. http://www.cs.cmu.edu/~sef/Orig-Smiley.htm. Accessed Mar 12 2024

Fischer A, Hess U (2017) Mimicking emotions. Curr Opin Psychol 17:151–155

Fischer B, Herbert C (2021) Emoji as affective symbols: affective judgments of emoji, emoticons, and human faces varying in emotional content. Front Psychol 12:645173

Franco CL, Fugate JM (2020) Emoji face renderings: exploring the role emoji platform differences have on emotional interpretation. J Nonverbal Behav 44(2):301–328

Fugate J, Franco CL (2021) Implications for emotion: Using anatomically based facial coding to compare emoji faces across platforms. Front psychol 12:605928

Ganster T, Eimler SC, Krämer NC (2012) Same same but different!? The differential influence of smilies and emoticons on person perception. Cyberpsychol Behav Social Netw 15(4):226–230

Gantiva C, Sotaquirá M, Araujo A, Cuervo P (2020) Cortical processing of human and emoji faces: an ERP analysis. Behav Inform Technol 39(8):935–943

Gantiva C, Araujo A, Castillo K, Claro L, Hurtado-Parrado C (2021) Physiological and affective responses to emoji faces: effects on facial muscle activity, skin conductance, heart rate, and self-reported affect. Biol Psychol 163:108142

Gawne L, McCulloch G (2019) Emoji as digital gestures. Language@Internet, 17, 2, Available at https://www.languageatinternet.org/articles/2019/gawne

Glazer T (2017) On the virtual expression of emotion in writing. Br J Aesthet 57(2):177–194

Glazer T (2018) The part-whole perception of emotion. Conscious Cogn 58:34–43

Glazer T (2019) The social amplification view of facial expression. Biol Philos 34(2):33

Glazer T (2022) Emotionsha**: a situated perspective on emotionreading. Biology Philos 37(2):13

Glazer T (2023) Expressing 2.0. Anal Philos. https://doi.org/10.1111/phib.12308

Glikson E, Cheshin A, Kleef GAV (2018) The dark side of a smiley: effects of smiling emoticons on virtual first impressions. Social Psychol Personality Sci 9(5):614–625

Goren CC, Sarty M, Wu PY (1975) Visual following and pattern discrimination of face-like stimuli by newborn infants. Pediatrics 56(4):544–549

Griffiths PE, Scarantino A (2009) Emotions in the wild: the situated perspective on emotion. In: Robbins P, Aydede M (eds) The Cambridge handbook of situated cognition. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Guido G, Pichierri M, Pino G, Nataraajan R (2019) Effects of face images and face pareidolia on consumers’ responses to print advertising: an empirical investigation. J Advertising Res 59(2):219–231

Haxby JV, Hoffman EA, Gobbini MI (2000) The distributed human neural system for face perception. Trends Cogn Sci 4(6):223–233

Hilpinen R (1992) On artifacts and works of art. Theoria 58(1):58–82

Hochschild AR (1983) The Managed Heart: Commercialization Of Human Feeling. University of California Press, Berkeley, Los Angeles, London

Jack, R. E., Garrod, O. G., Yu, H., Caldara, R., & Schyns, P. G. (2012). Facial expressions of emotion are not culturally universal. Proceed Nat Academy Sci 109(19):7241–7244

Jack RE, Sun W, Delis I, Garrod OG, Schyns PG (2016) Four not six: revealing culturally common facial expressions of emotion. J Exp Psychol Gen 145(6):708

Jakobsen KV, Hunter BK, Simpson EA (2023) Pareidolic faces receive prioritized attention in the dot-probe task. Atten Percept Psychophys 85(4):1106–1126

Keys RT, Taubert J, Wardle SG (2021) A visual search advantage for illusory faces in objects. Atten Percept Psychophys 83:1942–1953

King A (2018) A Plea for Emoji. The American Society for aesthetics: an association for aesthetics. Crit Theory arts 38(3):1–3

Krkač K (2020) Wittgenstein’s four-stroke faces and the idea of visual philosophy. Wittgenstein-Studien 11(1):31–52

Langton SR, Law AS, Burton AM, Schweinberger SR (2008) Attention capture by faces. Cognition 107(1):330–342

Liao W, Zhang Y, Huang X, Xu X, Peng X (2021) Emoji, I can feel your pain–neural responses to facial and Emoji expressions of pain. Biol Psychol 163:108134

Liu M (2023) Are you really smiling? Display rules for emojis and the relationship between emotion management and psychological well-being. Front Psychol 14:1035742

Lohmann K, Pyka SS, Zanger C (2017) The effects of smileys on receivers’ emotions. J Consumer Market 34(6):489–495

Maier E (2023) Emojis as pictures. Ergo, 10

Marino G (2022) Colon + hyphen + right paren: at the origins of face semiotics from smileys to memes. Signs Soc 10(1):106–125

Matsumoto D, Yoo SH, Fontaine J, Grossi E (2008) Map** expressive differences around the world: the relationship between emotional display rules and individualism versus collectivism. J Cross-Cult Psychol 39(1):55–74

Neel LA, McKechnie JG, Robus CM, Hand CJ (2023) Emoji alter the perception of emotion in affectively neutral text messages. J Nonverbal Behav 47(1):83–97

Newen A, Wel**hus A, Juckel G (2015) Emotion recognition as pattern recognition: the relevance of perception. Mind Lang 30(2):187–208

Noble E, Wodehouse A, Robertson DJ (2023) Face pareidolia in products: the effect of emotional content on attentional capture, eagerness to explore, and likelihood to purchase. Appl Cogn Psychol 37(5):1071–1084

Olk B, Garay-Vado AM (2011) Attention to faces: effects of face inversion. Vision Res 51(14):1659–1666

Ong WJ (1982) Orality and literacy: the technologizing of the word. Routledge, London, New York

Osler L (2020) Feeling togetherness online: a phenomenological sketch of online communal experiences. Phenomenol Cogn Sci 19(3):569–588

Palagi E, Celeghin A, Tamietto M, Winkielman P, Norscia I (2020) The neuroethology of spontaneous mimicry and emotional contagion in human and non-human animals. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 111:149–165

Palermo R, Rhodes G (2007) Are you always on my mind? A review of how face perception and attention interact. Neuropsychologia 45(1):75–92

Palmer CJ, Clifford CW (2020) Face pareidolia recruits mechanisms for detecting human social attention. Psychol Sci 31(8):1001–1012

Plebani M, Berto F (2019) Logica con i social network. Carocci

Piredda G (2020) What is an affective artifact? A further development in situated affectivity. Phenomenol Cognitive Sci 19: 549–567

Prochazkova E, Prochazkova L, Giffin MR, Scholte HS, De Dreu CK, Kret ME (2018) Pupil mimicry promotes trust through the theory-of-mind network. Proc Natl Acad Sci 115(31):E7265–E7274

Reid VM, Dunn K, Young RJ, Amu J, Donovan T, Reissland N (2017) The human fetus preferentially engages with face-like visual stimuli. Curr Biol 27(12):1825–1828

Rekow D, Baudouin JY, Brochard R, Rossion B, Leleu A (2022) Rapid neural categorization of facelike objects predicts the perceptual awareness of a face (face pareidolia). Cognition 222:105016

Rossano F (2013) Gaze in conversation. In: Sidnell J, Stivers T (eds) The handbook of conversation analysis. Blackwell Publishing. Oxford.

Russell JA (2003) Core affect and the psychological construction of emotion. Psychol Rev 110(1):145

Saarinen JA (2019) Paintings as solid affective scaffolds. J Aesthet Art Crit 77(1):67–77

Scarantino A (2017) How to do things with emotional expressions: the theory of affective pragmatics. Psychol Inq 28(2–3):165–185

Scarantino A (2019) Affective pragmatics extended: from natural to overt expressions of emotions. The social nature of emotion expression: what emotions can tell us about world, pp. 49–81

Schachter S, Singer J (1962) Cognitive, social, and physiological determinants of emotional state. Psychol Rev 69(5):379

Smortchkova J (2022) Face perception and mind misreading. Topoi 41(4):685–694

Sperber D, Hirschfeld L (2007) Culture and Modularity. In: Carruthers P, Laurence S, Stich S (eds) The innate mind: culture and cognition. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 149–164

Stearns PN, Stearns CZ (1985) Emotionology: clarifying the history of emotions and emotional standards. Am Hist Rev 90(4):813–836

Tigwell GW, Flatla DR (2016) September Oh that’s what you meant! reducing emoji misunderstanding. In: Proceedings of the 18th international conference on human-computer interaction with mobile devices and services adjunct. pp. 859–866

Tinbergen N, Perdeck AC (1950) On the stimulus situation releasing the begging response in the newly hatched Herring Gull Chick (Larus argentatus Pont). Behaviour 3:1–39

Todorov A, Olivola CY, Dotsch R, Mende-Siedlecki P (2015) Social attributions from faces: determinants, consequences, accuracy, and functional significance. Ann Rev Psychol 66:519–545

Valenzuela-Gálvez ES, Garrido-Morgado A, González-Benito Ó (2023) Boost your email marketing campaign! Emojis as visual stimuli to influence customer engagement. J Res Interact Mark 17(3):337–352

Van Kleef GA (2009) How emotions regulate social life: the emotions as social information (EASI) model. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 18(3):184–188

Van Kleef G (2017) The social effects of emotions are functionally equivalent across expressive modalities. Psychol Inq 28(2–3):211–216

Viola M (2022) Seeing through the shades of situated affectivity. Sunglasses as a socio-affective artifact. Philosophical Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515089.2022.2118574

Viola M (2023) Masked faces A tale of functional redeployment between biology and material culture. In Leone, M. (Ed.) The Hybrid Face: Paradoxes of the Visage in the Digital Era. Taylor & Francis, 1–21

Van Kleef GA, Van den Berg H, Heerdink MW (2015) The persuasive power of emotions: effects of emotional expressions on attitude formation and change. J Appl Psychol 100(4):1124

Wall HJ, Kaye LK, Malone SA (2016) An exploration of psychological factors on emoticon usage and implications for judgement accuracy. Comput Hum Behav 62:70–78

Widen SC, Russell JA (2010) Differentiation in preschooler’s categories of emotion. Emotion 10(5):651–661

Yin RK (1969) Looking at upside-down faces. J Exp Psychol 81(1):141-145

Zapf D (2002) Emotion work and psychological well-being: a review of the literature and some conceptual considerations. Hum Resource Manage Rev 12(2):237–268

Zerilli J (2019) Neural reuse and the modularity of mind: where to next for modularity? Biol Theory 14(1):1–20

Acknowledgements

Many ideas from this paper are grounded in the time I spent as a PostDoc research fellow within the ERC project FACETS at the University of Turin (2019–2022). I am also indebted to Enrico Terrone and to the attendance of the workshop he organized in Genoa in May 2023 within his ERC project PEA for many valuable insights, and to Marco Facchin, Gabriele Marino, Maria Oliva, and two anonymous referees for the many useful comments on an earlier version of this manuscript. In particular, I owe the thought-provoking questions discussed in footnotes 8 and 11 to Reviewer1 and Marco Facchin, respecitvely.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi Roma Tre within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author declares having no conflict of interest with respect to the present paper.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Viola, M. Almost Faces? ;-) Emoticons and Emojis as Cultural Artifacts for Social Cognition Online. Topoi (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11245-024-10026-x

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11245-024-10026-x