Abstract

Tracer tests in natural porous media sometimes show abnormalities that suggest considering a fractional variant of the advection–diffusion equation supplemented by a time derivative of non-integer order. We are describing an inverse method for this equation: It finds the order of the fractional derivative and the coefficients that achieve minimum discrepancy between solution and tracer data. Using an adjoint equation divides the computational effort by an amount proportional to the number of freedom degrees, which becomes large when some coefficients depend on space. Method accuracy is checked on synthetical data, and applicability to actual tracer test is demonstrated.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Abramowitz, M., Stegun, I.A.: Handbook of Mathematical Functions with Formulas, Graphs and Mathematical Tables, 10th edn. Dover, New York (1972)

Baker, L.E.: Effects of dispersion and dead-end pore volume in miscible flooding. Soc. Pet. Eng. J. 17, 319 (1977)

Benson, D.A., Meerschaert, M.M.: A simple and efficient random walk solution of multi-rate mobile/immobile mass transport equations. Adv. Water Res. 32, 532–539 (2009)

Byrd, R.H., Lu, P., Nocedal, J., Zhu, C.: A limited memory algorithm for bound constrained optimization. SIAM J. Sci. Stat. Comput. 16(5), 1190–1208 (1995)

Cada, M., Torrilhon, M.: Compact third-order limiter functions for finite volume methods. J. Comput. Phys. 228, 4118–4145 (2009)

Chavent, G.: Identification of functional parameters in partial differential equations. In: Goodson, R.E., Polis, M. (eds.) Proceedings of the Joint Automatic Control Conference in Identification of Parameters in Distributed Systems. pp. 31–48. ASME, New York (1974)

Chavent, G.: Nonlinear Least Squares for Inverse Problems. Theoretical Foundations and Step-by-Step Guide for Applications. Springer, Berlin (2009)

Coats, K.H., Smith, B.D.: Dead-end pore volume and dispersion in porous media. Soc. Pet. Eng. J. 4(1), 73–84 (1964)

Deans, H.A.: A mathematical model for dispersion in the direction of flow in porous media. Soc. Pet. Eng. J. 3, 49 (1963)

Diethelm, K., Ford, N.J., Freed, A.D., Luchko, Y.: Algorithms for the fractional calculus: a selection of numerical methods. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 194, 743–773 (2005)

Galucio, A.C., Deü, J.F., Mengué, S., Dubois, F.: An adaptation of the Gear scheme for fractional derivatives. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 195, 6073–6085 (2006)

Gaudet, J.P., Jégat, H., Vachaud, V., Wierenga, J.P.: Solute transfer, with exchange between mobile and stagnant water, through unsaturated sand. Soil Sci. Am. J. 41(4), 665 (1977)

Gerschgorin, S.: Uber die Abgrenzung der Eigenwerte einer Matrix. Izv. Akad. Nauk. USSR Otd. Fiz.-Mat. Nauk 6, 749–754 (1931)

Ghazizadeh, H.R., Azimi, A., Maerefat, M.: An inverse problem to estimate relaxation parameter and order of fractionality in fractional single-phase-lag heat equation. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 55, 2095–2101 (2012)

Gou, T., Sandu, A.: Continuous versus discrete advection adjoints in chemical data assimilation. Atmos. Environ. 45, 4868–4881 (2011)

Haggerty, R., McKenna, S.A., Meigs, L.C.: On the late-time behavior of tracer test breakthrough curves. Water Resour. Res. 36(12), 3467–3479 (2000)

Jittorntrum, K.: An implicit function theorem. J. Optim. Theory Appl. 25(4), 575–577 (1978)

Latrille, C., Cartalade, A.: New experimental device to study transport in unsaturated porous media. In: Birkle, Torres-Alvarado (eds.) Water–Rock Interaction, pp. 299–302. Taylors and Francis Group, London (2010)

Latrille, C., Néel, M.C.: Transport study in unsaturated porous media by tracer test experiment in a dichromatic X-ray experimental device. In: Sixth International Conference in Tracers and Tracing Methods (Tracer 6), Oslo, June 2011, EPJ Web of Conferences (2012)

Liu, F., Zhuang, P., Burrage, K.: Numerical methods and analysis for a class of fractional advection-dispersion models. Comput. Math. Appl. 64, 2990–3007 (2012)

Liu, Q., Liu, F., Turner, I., Anh, V., Gu, Y.T.: A RBF meshless approach for modeling fractional mobile/immobile transport model. Appl. Math. Comput. 226, 247–336 (2014)

Maryshev, B., Cartalade, A., Latrille, C., Joelson, M., Néel, M.C.: Adjoint state method for fractional diffusion: parameter identification. Comput. Math. Appl. 66, 630–638 (2013)

Néel, M.C., Zoia, A., Joelson, M.: Mass transport subject to time-dependent flow with nonuniform sorption in porous media. Phys. Rev. E 80, 05631 (2009)

Neupauer, R., Wilson, J.: Adjoint method for obtaining backward and travel time probabilities of a conservative groundwater contaminant. Water Resour. Res. 35(11), 3389–3398 (1999)

Neupauer, R., Wilson, J.: Forward and backward location probabilities for sorbing solutes in groundwater. Adv. Water Res. 27, 689–705 (2004)

Nocedal, J., Wright, S.J.: Numerical Optimization. Springer, Berlin (1999)

Ouloin, M., Maryshev, B., Joelson, M., Latrille, C., Néel, M.C.: Laplace-transform based inversion method for fractional dispersion. Transp. Porous Media 98(1), 1–14 (2013)

Padilla, I.Y., Yeh, T.-C.J., Conklin, M.H.: The effect of water content on solute transport in unsaturated porous media. Water Resour. Res. 35(11), 3303–3313 (1999)

Samko, S.G., Kilbas, A.A., Marichev, O.I.: Fractional Integrals and Derivatives: Theory and Applications. Gordon and Breach, New York (1993)

Sardin, M., Schweich, D., Leu, F.J., van Genuchten, M.: Modeling the nonequilibrium transport of linearly interacting solutes in porous media: a review. Water Resour. Res. 27(9), 2287–2307 (1991)

Schumer, R., Benson, D.A., Meerschaert, M.M., Baeumer, B.: Fractal mobile/immobile solute transport. Water Resour. Res. 39(10), 1296 (2003)

Sun, N.-Z.: Inverse Problems in Groundwater Modeling, Theory and Applications of Transport in Morous Media, vol. 6. Kluwer, Dordrecht (1994)

Sun, N.Z., Yeh, W.W.G.: Coupled inverse problems in groundwater modeling: 1. Sensitivity analysis and parameter identification. Water Resour. Res. 26(10), 2507–2525 (1990)

Sykes, J.F., Wilson, J.L., Andrews, R.W.: Sensitivity analysis for steady state groundwater flow using adjoint operators. Water Resour. Res. 21(3), 359–371 (1985)

Townley, L.R., Wilson, J.L.: Computationally efficient algorithms for parameter estimation in numerical models of groundwater flow. Water Resour. Res. 21(12), 851–1860 (1985)

Tuan, V.K.: Inverse problem for fractional diffusion equation. Frac. Calc. Appl. Anal. 14(1), 31–54 (2011)

Valocchi, A., Quinodoz, H.A.M.: Application of the random walk method to simulate the transport of kinetically adsorbing solutes. In: Abriola LM (ed) Groundwater Contamination, Proceedings of the symposium held during the Third IAHS Scientific Assembly, pp. 35–42. IAHS publ. no. 185, Baltimore, MD

van Genuchten, MTh, Wierenga, P.J.: Mass transfer studies in sorbing porous media I. analytical solutions. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 40(4), 473–480 (1976)

Young, W.R.: Arrested shear dispersion and other models of anomalous diffusion. J. Fluid Mech. 193, 129–149 (1988)

Acknowledgments

The authors have been supported by Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR Project ANR-09-SYSC-015), B. Maryshev being postdoctoral fellow at DEN-DANS-DM2S-STMF-LATF CEA/Saclay in 2011–2013.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1: A Discrete Version of the Fractional MIM

Standard approximations to fractional integrals and derivatives define the discrete problem (6) whose solutions approximate those of (1).

1.1 Approximating Temporal Integrals and Derivatives

In \(p_2\partial _t+p_3\partial _tI_{0,+}^{1-\alpha }\) and in (2), the Riemann–Liouville integral \(I_{0,+}^{1-\alpha }\) accounts for past history since time \(t=0\). An approximation of order \(O(\Delta t^{2})\) is (Diethelm et al. 2005)

Combining (15) with the standard backward finite difference approximation \(\frac{y^{k}-y^{k-1}}{\Delta t}\) to the first-order derivative yields

with

1.2 Approximating Spatial Derivatives and Boundary Conditions

At each time step \(k>0\) and for each \(s\in \{1,\ldots ,N_{Sp}\}\), standard central finite differences

approximate \(-\partial _{x}(\partial _{x}p_1u-Vu)|_{s\Delta x}^{k\Delta t}\) at order \(O(\Delta x^2)\). Applying non-centered finite differences to the boundary conditions in (4) links \(u_{0}^{k}\) and \(u_{N_{Sp}+1}^{k}\) to immediately neighboring \(u_{s}^{k}\), but is accurate at first order only:

Hence, Eqs. (16) and (18) yield approximations to

at order \(O(\Delta x)+O(\Delta t)\) for each \(s\in \{1,\ldots ,N_{Sp}\}\) representing an interior point of \([0,\ell ]\) and each index \(k>0\). Equating them to zero and eliminating \(u_{0}^{k}\) and \(u_{N_{Sp}+1}^{k}\) with the help of (19) yields a system of equations determining the \(u_s^k\) that approximate the \(u(s\Delta x, k\Delta t)\) at interior points of \([0,\ell ]\). It accounts for solute injection at column inlet. Remembering the initial condition, we set these equations in the compact form (6) reproduced below

by defining linear map** A and array \(\mathbf r \). Each array \(\mathbf u \) of \({\mathcal D}(A)\equiv \{{\mathbf {u}}\in X{/}{\mathbf {u}}^{0}=0\}\) satisfies the initial condition included in (4) and A maps it onto array \(A({\mathbf {q}}, \mathbf{u })\) whose each rank k column \((A({\mathbf {q}}, \mathbf{u }))^{k}\) is

where \(\mathbf u ^k=(u_{1}^{k},\ldots ,u_{N_{Sp}}^{k})^\dag \) represents the rank k column of \(\mathbf u \). Matrices \(\mathbf{G }\) and \( \mathbf W (j,k)\) are defined at the end of the section, and array \(\mathbf r \) recollects the \(r_s^k\) defined by

Each rank k column \((r_{1}^{k},\ldots ,r_{N_{Sp}}^{k})^\dag \) of \(\mathbf r \) being noted \(\mathbf r ^k\), (6) is equivalent to the system of equations

With \(\mu =\frac{p_1\Delta t}{\Delta x^{2}}\) and \(\nu =\frac{V\Delta t}{2\Delta x}\), the entries \(g_{s,s^{\prime }}\) of \(\mathbf G \) are

where all interior diagonal entries exhibit the same \(\varOmega _s=2\mu \) (for \( s\ne 1\) and \(s\ne N_{Sp}\)), while boundary conditions (19) result into \( \varOmega _1=\mu (1+\frac{1}{2+\mu {/}\nu })\) and \(\varOmega _{N_{Sp}}=\mu +\nu \) at both ends. We see that matrix \(\mathbf G \) depends on \(\mathbf q \), \(\Delta x\) and \(\Delta t\). The \(\mathbf W (j,k)\) are \(N_{Sp}\times N_{Sp}\) diagonal matrices of entries \((\mathbf W (j, k))_{s,s}=W_s(j,k)\). In (20), each \(\mathbf W (j,k)\) operates on columns of rank smaller than k stored in \(\mathbf u \).

Using (20) will help us seeing that problem (6) has exactly one solution in \({\mathcal D}(A)\) provided these parameters make matrix \(\mathbf G \) invertible.

1.3 Well-Posedness of (6)

If \(\mathbf G \) is invertible, we easily determine the single solution \({\mathbf {u}}_{\mathbf {q}}\) of (22) in \({\mathcal D}(A)\) by setting \(\mathbf{u }^{0}=0\) and recursively solving Eq. (22), increasing k from 1 to \(N_T\). Gershgorin circle theorem (Gerschgorin 1931) gives us a sufficient condition for matrix \(\mathbf G \) invertibility in the form of

\(\delta _{i,j}\) being Kronecker index. This condition is satisfied when \( \mathbf{q }\) belongs to any closed convex set \( {Q}_\varepsilon = {R}_+\times [\frac{V\Delta t}{\Delta x}+\varepsilon ,+\infty [^{n+1}\times {R}_+^{n+1}\times [0,1]\) with \(\varepsilon >0\) arbitrarily small.

By implicit function theorem (Jittorntrum 1978), the map** \(\mathbf q \mapsto \mathbf u _{{\mathbf {q}}}\) is of \({\mathcal C}^\infty \) class in \(Q_\varepsilon \), matrices \(\mathbf G \) and \(\mathbf W (j,k)\) having elements of class \({\mathcal C}^\infty \) in \( {Q}_\varepsilon \) with respect to the components of \( \mathbf{q }\).

1.4 Numerical Scheme Accuracy

We validate the above scheme and fix \(\Delta x\) and \(\Delta t\) by considering a \({\mathcal R}\ne 0\) so that the continuous problem (1 and 4) with \(C_0=0\) has an exact solution which we compare with the still noted \(u_s^k\) issues of the above scheme. We set

and take \(\sigma \) defined by

\(u(x,t)\equiv t\varphi _0(x)\) solves (1 and 4) provided we set

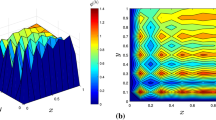

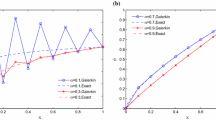

Steps \(\Delta x\) and \(\Delta t\) must satisfy \(p_{2}(s\Delta x)> \frac{V\Delta t}{\Delta x}\) to ensure \(\mathbf q \in Q_\varepsilon \). For instance, with \(L=1\), \(p_1=0.05\), \(V=1\), \(\alpha =0.8\), \(p_2(x)=0.5+0.3\sin {(4\pi x})\) and \(p_3(x)=0.5-0.4\sin {(4\pi x)}\), taking \(N_{Sp}=360\) and \(\Delta t=\Delta x/10\) results into relative errors \(|\frac{u_s^k-u(s\Delta x,k\Delta t)}{u(s\Delta x,k\Delta t)} |\) smaller than \(2\times 10^{-4}\), for \(t<1\).

This gives us an idea of which grid we can use. A posteriori checks are applied, especially when parameter identification returns large Péclet numbers. In this case, the centered finite difference approximation used in “Approximating Spatial Derivatives and Boundary Conditions” section for the advection term \(V\partial _xu\) may be flawed by numerical diffusion. Hence, we compare with a modified version of the discrete direct problem (6) in which \(\frac{V}{6\Delta x}(3u_s^n+u_{s-2}^n-6u_{s-1}^n+2u_{s+1}^n)\) approximates \(V\partial _xu\). This is Eq. (4.9) of Cada and Torrilhon (2009) which corresponds to a flux limiter given by the first line of (3.8) in this reference, in view of the small \(\partial ^2_{x^2}u\) which we observe. Other a posteriori checks are comparisons with random walks whose probability density function is \(p_2u\), as in Ouloin et al. (2013).

Appendix 2: Discrete Adjoint State for Discrete Direct Problem (6)

The linear operator A is described by (20), which implies

for each \((\mathbf u ,\mathbf w )\) in \({\mathcal D}(A)\times X\). Matrices \(\mathbf G \) and \(\mathbf W (j,k)\) are defined in “Approximating Spatial Derivatives and Boundary Conditions” section, and each \(\langle \mathbf G {} \mathbf u ^{k}\cdot \mathbf w ^{k}\rangle _{ {R}^{N_{Sp}}}\) is equal to \(\langle \mathbf u ^{k}\cdot \mathbf G ^{\dagger } \mathbf w ^{k}\rangle _{ {R}^{N_{Sp}}}\), superscript \({\dagger }\) denoting transpose. Re-arranging the double sum in the right-hand side of (25) proves that the adjoint \(A^{*}\) of A is the operator that transforms each array \(\mathbf w \) of X into array \(A^{*}(\mathbf q ,\mathbf w )\) whose each column of rank k is

This implies that Eq. (13) is equivalent to the set of all equations

obtained for \(0\le k\le N_T\). When \(\mathbf G \) is invertible it is the same for \( \mathbf G ^{\dagger }\); hence, the system of all these equations has exactly one solution in  because the final simulation time T is such that \(\max \{{\bar{k}} / ({\bar{k}},{\bar{s}})\in {\mathcal M}^{(d)}\}<N_{T}\) which implies \((\frac{\partial f_{{\bar{s}}}^{{\bar{k}}}}{\partial \mathbf u } )^{N_{T}}(\mathbf q , \mathbf u )=0\), hence \(\varvec{\psi }^{N_T}=0\) because \(\mathbf G \) is invertible. Then, for each \(k<N_T\) Eq. (27) is of the form of

because the final simulation time T is such that \(\max \{{\bar{k}} / ({\bar{k}},{\bar{s}})\in {\mathcal M}^{(d)}\}<N_{T}\) which implies \((\frac{\partial f_{{\bar{s}}}^{{\bar{k}}}}{\partial \mathbf u } )^{N_{T}}(\mathbf q , \mathbf u )=0\), hence \(\varvec{\psi }^{N_T}=0\) because \(\mathbf G \) is invertible. Then, for each \(k<N_T\) Eq. (27) is of the form of

and has exactly one solution in \({R}^{N_{Sp}}\) entirely determined by \(\varvec{\psi }^{k+1},\ldots ,\varvec{\psi }^{N_T}\), \(\mathbf q \), \(\theta \) and \(\mathbf C \). All these \(\varvec{\psi }^{k}\) form the unique solution of Eq. (13) in \({\mathcal D}(A^*)\), which we call \(\varvec{\psi }_\mathbf{q }\).

Appendix 3: The Derivatives of E w.r.t. the Parameters

The adjoint problem (13) depends on the differential of f w.r.t. \(\mathbf u \), and determining the gradient of E w.r.t. \(\mathbf q \) also needs the derivatives of f, A, and \(\mathbf r \) w.r.t. the entries \(q_h\) of \(\mathbf q \). Though standard algebra returns these derivatives, two points are worth being mentioned.

First, for \(j=2,3\), the \(\partial E{/}\partial p_{j}^{(i)}\) are obtained by applying chain rule to (14) and (5).

Then, the derivative w.r.t. \(\alpha \) involves \(\frac{\partial {\mathcal I}^0}{\partial \alpha }\), \(\frac{\partial ({\mathcal I}^{j-1,k-1}-{\mathcal I}^{j-1,k-1})}{\partial \alpha }\) and \(\frac{\partial f_{{\bar{s}}}^{{\bar{k}}}}{\partial \alpha }\) for which we need the digamma function \(\frac{\varGamma ^{\prime }}{\varGamma }\) (Abramowitz and Stegun 1972)

where \(\gamma \) is Euler constant. We obtain

and

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Maryshev, B., Cartalade, A., Latrille, C. et al. Identifying Space-Dependent Coefficients and the Order of Fractionality in Fractional Advection–Diffusion Equation. Transp Porous Med 116, 53–71 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11242-016-0764-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11242-016-0764-1