Abstract

This paper presents a meta-ranking of philosophy journals based on existing rankings, and a new ranking of philosophy journals developed through a survey involving a thousand authors (351 respondents, data collection May 2022) of articles from the most recent issues of 40 general philosophy journals. In addition to assessing journal quality, data were gathered on various variables such as gender, age, years in academia, number of refereed publications, area of specialization, and journal affiliation (as an author or editor). Findings indicate that only area of specialization and affiliation have some influence on respondents’ assessments. Authors affiliated with particular journals rate them higher than non-affiliated authors. The paper discusses criticisms of both citation-based and survey-based journal rankings, and offers words of caution regarding the practical use of rankings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

We think a lot about our own field—more, perhaps, than people working in other academic disciplines. This may be unsurprising, because philosophy, unlike many other fields, has an immense array of tools that facilitate such thinking. But when it comes to journal rankings, we are far less self-reflective than most other scholars. In many fields, journal rankings are published in the best journals, and are continuously evaluated, criticized, revised, and regularly updated. Philosophy, by contrast, has no ranking rigorously developed on the basis of up-to-date bibliometric and scientometric conventions (Merllié, 2010; Stekeler-Weithofer, 2010). This paper makes a start filling that lacuna. It presents a meta-ranking based on existing rankings of philosophy journals, and develops a new ranking based on a survey among authors of articles that appeared in the most recent issues of 40 general philosophy journals.

The lack of research in philosophy on journal rankings, in comparison to other fields, sparks speculation about its underlying reasons. One possibility lies in our field’s more diverse range of methods, traditions, and topics. Another explanation could be that journal ranking papers, employing methods outside the traditional philosophical toolkit, do not align with what we consider typical philosophy style, presenting results in ways that most of us, unlike social scientists who are accustomed to detailed methods and results sections, do not experience as particularly attention-grabbing.

Nevertheless, empirical work has explored topics such as gender and ethnic diversity, ideological diversity, and publication networks in philosophy (Bourget & Chalmers, 2014; Conklin et al., 2023; Demarest et al., 2017; Dobbs, 2020; Haslanger, 2008; Hassoun et al., 2022; Iliadi et al., 2020; Noichl, 2021; Peters et al., 2020; Schwitzgebel & Jennings, 2017; Schwitzgebel et al., 2021). This body of work has hopefully broadened our receptiveness to research presented in non-traditional philosophical formats. This paper contributes to this literature.

Whatever explains the absence of published work on journal rankings in philosophy, we do not care less about rankings than other academics. Brian Leiter, for instance, has developed several rankings that are widely discussed in our field. His rankings use survey data. Google Scholar, Scimago, and Scopus provide rankings based on various measures of article or journal impact. The European Reference Index for the Humanities (ERIH) categorizes philosophy journals based on the input of experts. And many professional organizations and universities have their own rankings.

While philosophers may differ in the weight they assign to journal rankings, it is evident that these rankings frequently serve as indicators of the quality and impact of philosophical work. They play a crucial role in decisions regarding hiring, remuneration, and promotion. They determine publication strategies of individual researchers. Funding bodies and their reviewers are influenced by rankings when making decisions. Journal rankings influence academic awards, and shape, in not always too subtle ways, the recognition and accolades we receive from our colleagues.

It is important to recognize that there is significant criticism of journal rankings in various fields, including philosophy. Journal rankings often favor established viewpoints, may discourage innovative interdisciplinary work, and can be biased against minority perspectives. These criticisms are discussed later in the paper. However, it is plausible to maintain that if rankings are to be used, then they should be robustly established according to widely accepted standards. Therefore, this paper offers two things. It presents a meta-ranking of general philosophy journals based on information from relevant bibliometric databases and metrics, using standard bibliometric techniques. And it develops a new ranking based on a methodology of high repute, the Active Scholar Assessment methodology (Currie & Pandher, 2011).

The remaining sections of the paper are structured as follows. The paper begins by giving a concise overview of prior research on ranking philosophy journals, providing the necessary background for our study. It then proceeds to describe the first study, which is the meta-ranking. This includes an explanation of the approach used to aggregate the rankings, the presentation of results, and the robustness tests conducted. The paper then moves on to the second study. This section discusses the methodology, presents the results, and compares them with existing philosophy journal rankings, including the meta-ranking. Subsequently, limitations are discussed as well as some more general criticisms of journal rankings. The paper ends with a word of caution.

1 Background

It helps to distinguish the following three concepts: rankings, data, and metrics. This distinction is standard in the bibliometric and scientometric literature (Aksnes et al., 2019; Walters, 2017; Waltman, 2016). More details about existing rankings in philosophy (Brian Leiter’s, etc.) as well as relevant databases (Google Scholar, etc.) can be found in the Supplementary Materials.

First: rankings. A ranking is simply an ordering of journals. Various individuals and organizations have developed actual rankings of philosophy journals. Examples are Brian Leiter’s rankings (based on opt-in online surveys), the “Philosophy” list of the European Reference Index for the Humanities (ERIH), the Scimago “Philosophy” and “History and Philosophy of Science” lists, and the many lists that are designed by philosophy departments for hiring and promotion decisions.

Second: data. Relevant data include citations of journal articles in journal articles, in book chapters (edited volumes), in books, and in other publications, which are gathered by various organizations in bibliographic databases, some publicly available, others subscription-based. The most important ones are Web of Science, Scopus, and Google Scholar. For survey-based approaches to journal ranking, such as Brian Leiter’s rankings and the survey-based ranking developed in this paper, the data are respondents’ answers to survey items.

For citations, the construction of the citation pool depends on such factors as time (typically only citations to an article within a maximum of two years from the date of publication are included, although citation windows of five years are also used), publication type (typically academic journals, but increasingly also books published by academic publishers, sometimes including conference proceedings and trade publications, but not always), language (mostly English), publication nationality (international or also national journals), and a host of other non-trivial issues that we do not discuss here (Walters, 2017).

Third: metrics. Here we have to think of such measures the Journal Impact Factor (JIF), which is among the oldest metrics, the h-index, the Eigenfactor Score, the number of citations per paper, or less orthodox methods as the Condorcet method that Brian Leiter uses, and which has attracted some attention in the scientometric literature (Subochev et al., 2018). JIF was developed by Eugene Garfield (1955), initially as an attempt to help librarians decide on which journal subscriptions to take out. Garfield also developed the Science Citation Index, now part of the World of Science. The JIF is calculated by taking the total number of citations, in a given year, to articles published in the journal in the two previous years, divided by the total number of articles published in the journal in the two previous years. A five-year impact factor can be calculated analogously. The h-index of a journal is the largest h such that the journal has h publications such that each of these h publications is cited at least h times. It was developed by a physicist, Jorge Hirsch (2005), to measure the scientific output of individual researchers, particularly in his own field, but the h-index has readily been extended to other fields and to journals instead of researchers. Important here is that some metrics will apply normalization techniques to define metrics that take into account the considerable differences between citation practices between fields.

The interaction of metrics and data can lead to considerable confusion. Consider the Scimago Journal Rank. This ranking is published by Scimago. It does not, however, have its own metrics or data. To calculate the ranking, Scimago uses the PageRank algorithm of Google Scholar, and applies it to data from Elsevier’s Scopus database. More generally, therefore, we cannot sensibly speak of, say, “the” h-index of a journal without specifying the underlying database. If an article is cited by another article in a journal that does not appear in the database, that citation is missed. Philosophy as a field is decidedly underrepresented in the Web of Science database, and non-English and national publications are excluded from Web of Science and Scopus. As it can be expected that some work is more often cited in such publications than others (think of citations to moral and political philosophy in national policy-oriented publications), these effects likely do not cancel out across philosophical subdisciplines. In other terms, while rankings, data, and metrics are conceptually distinct, they often come intertwined. Leiter’s ranking is, it seems, currently the only ranking using the Condorcet method, and Leiter does not report alternative rankings based on the same data. The Scimago Journal Rank is only available for Scopus data, while the Eigenfactor is only available for Web of Science data.

Another relevant observation is that some metrics compare citations against a class of reference publications for the purpose of normalization. This generally requires that a set of journals be specified representing a particular discipline or subdiscipline. Precise reference classes for philosophy have not been provided yet, which has led to inconsistent normalization. Consider Scimago again. They provide two lists that are relevant for our purposes: a “Philosophy” list, with 651 journals (2019), and a “History and Philosophy of Science” list, with 169 journals (2019). The criteria for including journals in these categories make them highly unreliable for the purposes of our profession. The “Philosophy” list includes, besides Noûs and Philosophical Review, such journals as Political Psychology, European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, and Journal of Sociolinguistics in the top 20. The “History and Philosophy of Science” list includes Psychological Bulletin, Journal of Econometrics, and Journal of Sex Research in the top 10. This does not affect the reported h-indices of the individual journals. It may, however, affect the reported values of the Scimago Journal Rank, of which the precise formula is unfortunately communicated with insufficient precision to fully verify this claim. And it surely affects the relative ranks that Scimago reports.

It should be noted that it is possible to calculate some of metrics (mainly the h-index and its cognates) for databases that do not typically publish these metrics. An oft-used software package for this purpose is Anne-Wil Harzing’s Publish or Perish (version 7, 2019). This package allows researchers to calculate metrics themselves instead of relying on metrics provided by third parties. It is important to emphasize that the reliability of the retrieved metrics is somewhat difficult to gauge. Publish or Perish downloads articles/citations from the internet, and then calculates resulting metrics. Google Scholar itself, by contrast, has a larger dataset to its disposal. This entails that it would not be correct to compare, say, the hI-index we calculate using Publish or Perish (on the basis of Google Scholar data!) with the hI-index that Google Scholar itself reports. When we compare metrics across journals, they should be calculated on the basis of the same underlying database, using the same software. This is sometimes ignored.

2 Meta-ranking

Metrics were computed and/or retrieved as per Brian Leiter’s ranking (“general” philosophy journals, 2018), Scopus and Scimago (2019), Google Scholar (collected using Publish or Perish, data collection in 2021), Google Scholar (2019), and Web of Science (2019). A quick analysis of the way these metrics correlate (pairwise Spearman rank correlations) yields coefficients ranging from 0.14 (between Scimago h-index and Web of Science Journal Normalized Citation Impact, not statistically significant) or 0.38 (Google Scholar, two h-indices, p < 0.05) to 1.00 (Google Scholar, among various versions of the h-index, p < 0.001). About 40% of the coefficients are larger than 0.75, while some 15% are smaller than 0.50. The conclusion must be that even though some metrics tap into highly similar aspects of journal quality, most of them measure quite different aspects of the concept.

How do we aggregate these rankings? There are various approaches in the bibliometric literature. The simplest is to compute, for each metric, the induced ordinal ranking, and then to compute the average. In fact, we can construe averages in several ways, for instance along the lines of the three classical Pythagorean means (arithmetic, geometric, harmonic). This paper follows the literature by reporting the arithmetic and harmonic means, noting that, as Seiler and Wohlrabe (2014) show, these aggregation procedures entail slightly different types of biases (towards low and high rankings, respectively). These two rankings are presented in Table 1 (columns “AM” and “HM,” respectively).

It may appear a bit pedantic to introduce the harmonic means besides the more standard arithmetic means. The reason for reporting it is not just to align with what is standard in some of the bibliometric literature, but also to demonstrate to what extent decisions at the level of designing a metric have consequences for the relative position of the ranked journals. One could argue that if different aggregation procedures led to vastly diverging rankings, this would count against the aggregation procedure and/or the underlying rankings. The data do not lead to very big differences. For more than half of the journals, the difference between the arithmetic and harmonic means is at most 1, and for only one journal the difference is 4. Yet, for a journal such as Philosophical Quarterly its top-10 status (in our data) depends on the choice of aggregation method.

This is not to say that averaging is the best aggregation strategy. A disadvantage of this approach is that the resulting aggregate ranking is to some extent determined by the sheer availability of metrics for journals in our field. Information about the h-index and variants thereof is plentiful, but other metrics are scarce. So if we take an average, we may expect it to be skewed in favor of the h-index methodology. There are essentially two ways to address this difficulty.

2.1 Weighting

One is to develop an ex ante weighting of rankings on the basis of conceptual arguments about the specific metrics (ex ante in the sense that it precedes the statistical analysis). This can be done in various ways, but we believe that it is plausible to distinguish four kinds of metrics available for the journals in our sample. One is the h-index or variants: the Scimago h-index, Google Scholar h-index, g-index, hI (norm), hI (annual), hA, h5-index, and h5-median. One variable takes the average of all of these, where each metric is first transformed into an ordinal rank. The second category includes two metrics, each based on the idea of calculating the number of citations per document (Scimago cites per document and Google Scholar cites per paper). The third category is built on the idea of measuring the percentage of cited documents (Scopus Percentage Cited and Web of Science Percentage Cited). The fourth category takes the average of the Leiter rank and the ranks induced by Scimago (Scimago Journal Rank), Scopus (CiteScore), and Web of Science (Journal Normalized Citation Impact).

These four categorical metrics are then averaged again. Table 1 (column “Weighted”) reports this alternative ranking.

2.2 Principal component analysis

An altogether different approach assigns ex post weights to the metrics. It is ex post in that it assigns weightings to the metrics based on Principal Component Analysis (PCA), a common statistical tool used for dimension reduction. As pointed out in the introduction, philosophers are generally not very familiar with this type of tools. But PCA has been used more recently in research on the philosophical views of philosophers (Bourget & Chalmers, 2014), and is somewhat related to the technique of factor analysis that has attracted more attention from philosophers (van Eersel et al., 2019).

The assumption that underlies the use of PCA in the case at hand is that journal quality is a “latent” property of a journal such that each of the metrics offers a particular type of observation concerning this latent property. We can then use PCA to lay bare the latent property based on such observations. This approach is fairly common in the bibliometric literature (Bornmann et al., 2018). In line with this literature, and expressed in the jargon, we find that around 75% of the variance of journal quality is explained by one component. Factor loadings on this component help us to assign weights to the various metrics. Details of this procedure are unimportant here. The resulting PCA ranking is displayed in Table 1 (column “PCA”).

Table 2 presents the Spearman correlation coefficients for all meta-rankings and the most prominent extant journal rankings considered in this article, and Table 4 includes correlations for our new survey-based ranking, discussed below, as well. As one should expect, the PCA approach correlates very strongly with the other three meta-rankings (based on the arithmetic, harmonic, and weighted mean): correlations with these three meta-rankings are all above 0.96 (p < 0.001). This attests to the fact that the meta-rankings are fairly robust. Correlations with existing rankings range from 0.46 for Journal Normalized Citation Impact (Web of Science) to 0.95 (p < 0.05) for the h5-index as published by Google Scholar. It is also worth noting that among the existing rankings, CiteScore is the one that correlates most strongly with all four meta-rankings. Tentatively this might be a reason to prefer CiteScore as a source of information on a journal if it has no other rankings.

3 Survey ranking

The goal of this section is to present our new ranking of philosophy journals. A survey gathered input from active scholars to assess the quality of these journals (Currie & Pandher, 2011). This section explains the design of the survey, data collection, and results. Starting point was a pilot phase to test the survey and to determine which journals to include. The Supplementary Materials give details on the pilot.

3.1 Survey design and data collection

In view of the pilot and bibliometric standard practice, participants were invited who have published in the past year. All journals from the meta-rankings were included as well as the journals that were excluded in the meta-ranking because of missing rankings (Analytic Philosophy, Ergo, Philosophical Perspectives, Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, Midwest Studies in Philosophy, and Philosophical Topics). The resulting journals can be found in Table 5 (column “Journal”).

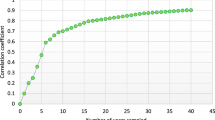

Per journal 25 authors were selected, working backwards starting from the most recent issue. Participants were invited through the Qualtrics software package, with the invitation sent to a total of 1,010 participants. 351 finished the survey completely, which is a response rate of 35%. This is considered adequate for bibliometric purposes.

The survey started with a brief explanation. Participants were informed that they were asked to rate journals on a scale from 1 (“low quality”) to 5 (“high quality”), and that we were interested in their “personal assessment of the journal’s quality,” and not in their assessment of “the journal’s reputation in the philosophy community.” Furthermore, it was stated that if a participant is “insufficiently familiar with the journal to assess its quality,” they should select the sixth option, “Unfamiliar with journal.” It was also made clear that the survey was fully anonymous, and that data will be retrieved, stored, processed, and analyzed in conformance with all applicable rules and regulations, and that participants could voluntarily cease cooperation at any stage. Then respondents were asked to assess the quality of all journals. The journals appeared in random order, which is the received strategy to control for decreasing interest among participants and for fatigue bias. Subsequently, participants were asked to provide information about their affiliation with journals (editorial board member, reviewer/referee, author), and a number of demographic questions were asked (gender, age, ethnicity/race, country of residence, area of specialization, number of refereed publications, etc.). An open question with space for comments concluded the survey.

The respondent characteristics are displayed in Table 3. Can we say something about the representativeness of the sample along such variables as gender and ethnicity? Conklin et al. (2023) estimate that 22% of philosophy papers published in the 2010s had a female first author. Hassoun et al. (2022) give an estimate of more than 10% for “top” philosophy journals and slightly more than 25% for “nontop” philosophy journals (no precise figures reported). Schwitzgebel and Jennings (2017) provide an estimate of around 10% female authors in “five leading journals.” Haslanger (2008) provides estimates for the first decade of the millennium that are very much in line with these figures. Figures ranging between 10 and 20% are also reported outside the Anglophone context (Araújo, 2019; Ávila Cañamares, 2020). This warrants the conclusion that the 17% of female respondents in our sample is sufficiently representative. Note also that, unlike the literature cited here above, the gender item was not binary, but had five alternatives: agender, gender fluid, non-binary, or third gender; female; male; any other sex/gender; prefer not to say. In the sample, 10% of the responses do not fall in the female and male categories. Assuming that the earlier literature has on average identified half of this 10% as female, the relevant number for reasons of comparison is 17% + 5% = 22%. We should say, then, that while the sample is predominantly male, it is not disproportionally male.

Ethnicity has also been examined in the literature. The estimates obtained by Schwitzgebel et al. (2021) entail (if we interpret their data correctly) that less than 20% of people earning a PhD in philosophy in the US in 2019 had a non-white ethnicity. Our sample has 26%, and is, then, slightly more ethnically diverse.

Existing research does not seem to provide reliable data about the other variables. One might, however, want to argue on methodological grounds that what matters here is not whether the sample of participants is sufficiently representative of the profession, but rather whether it is representative of the set of philosophers that were invited, that is, of the group of philosophers that published in the year before data collection in the selected journals. There is no fully reliable way to accomplish this. Even if we use first names as proxies (which some scholars have done using machine learning techniques), this is unsatisfactory for present purposes as there is a sizeable category of respondents not identifying as “male” or “female,” as well as a sizeable group of non-English first names. Despite this, however, we can be confident that the sample is sufficiently representative of our profession for the purposes of generating a new ranking.

3.2 Methodology and data

As said, journal’s quality is measured on a 5-point anchored Likert scale ranging from 1 (“low quality”) to 5 (“high quality”). To be precise, variable \({Q}_{ij}\) represents the quality judgment that respondent \(i\) assigns to journal \(j\). Variable \({A}_{ij}\) captures a respondent’s awareness. It assumes the value of 0 if respondent \(i\) does not find themselves (sufficiently) familiar with journal \(j\) to give it a ranking, and it assumes the value of 1 otherwise.

The average quality of journal \(j\) is then defined by \({Q}_{j}= \frac{1}{{n}_{j}} \sum_{i=1}^{{n}_{j}}{Q}_{ij}\), where nj is the total number of respondents who are aware of journal \(j\) (that is, the total number of respondents who have assessed journal \(j\)). Following McKercher, Law and Lam (2006), awareness-adjusted quality of journal \(j\) is defined as \({AQ}_{j}= \frac{{Q}_{j}}{5} \times \frac{{n}_{j}}{N} \times 100\). The motivation that underlies dividing by 5 is that 5 is the maximum quality assignment journal \(j\) could get, so \(\frac{{Q}_{j}}{5}\) captures the “relative” quality of journal \(j\). The number \(N\) is the total number of respondents. As a result, \(\frac{{n}_{j}}{N}\) is a measure of the “relative” awareness of the journal. If all respondents are aware of journal \(j\), the value of this fraction will be 1. If no one knows it, the value will be 0. One standard interpretation of \({AQ}_{j}\) is that it is somewhat similar to the concept of expected utility. The “utility” of publishing in journal j is its relative quality \(\frac{{Q}_{j}}{5}\). The “expectations” of publishing in journal \(j\) would be proportional to how widely it is known, a concept represented by \(\frac{{n}_{j}}{N}\). That is why some authors call this construct the importance to the field score. We use the more descriptive awareness-adjusted quality.

Since we are also interested in finding out whether the way a respondent ranks a journal depends on some of their characteristics, we also need a concept of awareness-adjusted quality at the respondent level, respondent quality. This construct is defined as \({RQ}_{ij}= \frac{{Q}_{ij}}{5} \times \frac{{n}_{j}}{N} \times 100\) if \(i\) has rated the quality of \(j\), and remains undefined if \(i\) is insufficiently aware of \(j\) to assess quality. Note that, just like awareness-adjusted quality \({AQ}_{j}\), respondent quality \({RQ}_{ij}\) adjusts for the awareness of the journal; but unlike \({AQ}_{j}\), the construct \({RQ}_{ij}\) considers the individual quality assessment that participant \(i\) gives to journal \(j\). This reflects the different use of the two variables: awareness-adjusted quality \({AQ}_{j}\) is used to determine the ultimate survey-based ranking, while respondent quality \({RQ}_{ij}\) figures in the statistical analyses conducted to find out what, if anything, is the influence of a respondent’s personal characteristics (age, affiliation, area of specialization, etc.) on their assessment of the quality of journals.

3.3 Ranking

Table 5 reports the resulting rankings. The second column reports the average quality \({Q}_{j}\) of journal \(j\), the third column reports the journal’s awareness score \({A}_{j}\), and the fourth column reports the journal’s awareness-adjusted quality \({AQ}_{j}\). The next two columns (“Quality ranking” and “Awareness-Adjusted Quality ranking”) display the ranking induced by the average quality and the awareness-adjusted quality, respectively.

We can see that the average quality ranges from 4.64 to 2.13, awareness from almost 97% to about 44%, and awareness-adjusted quality from about 90 to about 20. It may be slightly surprising that only about two-thirds of the respondents feel sufficiently familiar to assess the quality of Philosophical Issues and Philosophical Perspectives, and that no journal reaches a 100% awareness score. Yet, to appreciate the awareness scores, it is important to realize that they do not capture the familiarity with the journal name, but are elicited by asking people to consider whether they are sufficiently familiar with the journal to assess its quality. While it is likely the case that all professional philosophers are familiar with names of journals in the top 10, not all of them will consider themselves qualified to judge their quality.

How does this ranking compare with the meta-ranking presented in the previous section? Table 4 displays the pairwise Spearman rank correlations between the rankings induced by the quality and the awareness-adjusted quality measures, and the rankings that are used in the meta-ranking. It turns out that the quality and awareness-adjusted quality ranking correlate very highly with Brian Leiter’s 2018 “general philosophy” ranking. But correlation does not entail that they “agree.” While they agree on which journal should enter the top ten, they disagree about their ordering. For Leiter’s ranking, the ordering is: Philosophical Review, Mind, Noûs, Journal of Philosophy, Philosophy & Phenomenological Research, Australian Journal of Philosophy, Philosopher’s Imprint, Philosophical Studies, Philosophical Quarterly, Analysis. The quality ranking gets the following ordering: Noûs, Philosophy & Phenomenological Research, Mind, Philosophical Review, Journal of Philosophy, Australasian Journal of Philosophy, Philosophers’ Imprint, Philosophical Quarterly, Analysis, Philosophical Studies.

So if a high correlation does not mean that the present ranking agrees with Leiter’s ranking, then what does it mean? Leiter’s ranking is just as our ranking an attempt to find out the perceptions among professional philosophers of journal quality. This sets them apart from rankings based on such things as the h-index or the Scimago Journal Rank. If we had found a low correlation between Leiter’s ranking and our ranking, this would have suggested that the ranking developed in this section does not tap into the same construct, and that it may be just as different from Leiter’s as from the h-index or Scimago Journal Rank. In other words, finding a high correlation coefficient should be seen as evidence to the effect that it measures the quality perceptions of professional philosophers. However, it can be argued that our survey has been developed in a methodologically more rigorous manner than Leiter’s. So when it comes to making statements about how exactly the profession orders journals, the ranking presented in this paper is arguably a better guess than Leiter’s. Similarly, while the survey-based ranking is quite in line with Leiter’s, Table 4 shows that it is rather different from the meta-ranking. This suggests that the rankings do indeed distinguish two concepts: quality assessments made by professionals, and citation-based impact estimates. A qualified judgment about the relative merits of the two rankings has to wait until the last section of the paper.

3.4 Regression analysis

The survey data also allow us to answer the following question: to what extent does the assessment of the quality of a journal depend on specific characteristics of the person making the assessment? Is there any influence on a philosopher’s judgment about journal quality of, for instance, their gender, age, ethnicity, rank, years in academia, number of refereed publications, country, or area of specialization (AOS)? A straightforward regression of each individual journal’s average quality on these respondent characteristics yields mixed results. Gender, age, ethnicity, rank, years in academia, and refereed publications are statistically significant at the 5% level only in fewer than ten journals. An AOS in “Epistemology, etc.” or in “Ethics, etc.” only in one or two journals. The only striking finding here is that an AOS in “History, etc.” is statistically significant in slightly less than half of the journals, where the robustness of these findings is underscored by the fact that this is largely independent of whether we take a strict measure of AOS (where one counts as having a “History, etc.” AOS if one has not checked any box in the “Epistemology, etc.” or “Ethics, etc.” domain) or a more relaxed measure where one counts as having a “History, etc.” AOS when one has checked at least one box in that domain.

All in all, this should give us confidence to claim that there is no indication that the perception of journal quality depends on gender, ethnicity, or country of origin (Table 5).

A final (and different) question is whether a person’s assessment of a journal’s quality depends on whether the person is affiliated with the journal as an editor or author. We can test this in the following way. For each journal \(j\), the sample is divided in two: one group of respondents who are not editor nor author, another group of respondents who are author and/or editor. We then compute the average quality assessments of \(j\) in both groups, and conduct a t-test to see if the difference between the quality assessments is statistically significant. This is indeed the case. For more than 75% of the journals, affiliated respondents give a statistically significant higher quality assessment to a journal than non-affiliated respondents; for the remaining journals there is no statistically significant effect. The size of the difference varies considerably, however, from 0.162 to 1.470, where this has to be interpreted as a difference on the Likert scale ranging from 1 (“low quality”) to 5 (“high quality”). The average size is 0.5. That means that affiliated respondents give their “own” journals about half a Likert point more, on average. In sum, editors and authors are upwardly biased, but not a lot.

4 Discussion and conclusion

Philosophers care about the relative standing of their professional journals just as much as other academics. But unlike in other fields, work on journal rankings has not been published in philosophy journals. That is one of the reasons to carry out the research reported in this paper. The paper’s contributions are two-fold. It presents the first meta-ranking of philosophy journals, based on a variety of existing rankings. And it presents a new survey-based ranking of philosophy journals. The meta-ranking and the survey-based ranking were both construed using up-to-date standards of bibliometric rigor.

While this paper’s primary aim is to present methodologically rigorous work on journal rankings, some words of caution and criticism about journal rankings, and some observations about the limitations are in place. But let us start with the question of whether our results are sufficiently “surprising.”

4.1 Insights

What have we learned by going through this exercise? It is tempting to expect the answer to this question to refer to Brian Leiter’s rankings, particularly since the survey-based ranking correlates highly with his. Apart from questions about methodological rigor, the survey-based ranking, unlike Leiter’s ranking and other rankings, contains information about the familiarity of philosophers with particular journals, which as explained above may guide publication strategies. It may be useful to know that Philosophia and International Philosophical Quarterly are perceived to have very similar average quality (2.43 and 2.33, respectively), but that Philosophia has an awareness score (74.07) placing it in the range of journals such as Thought (71.23), Inquiry (78.92), and Ratio (78.35), which all have average quality scores above 3. In contrast, International Philosophical Quarterly has an awareness score of 43.88. Moreover, as we saw, a high level of correlation does not entail that the rankings agree.

Yet much of the value of having conducted a survey-based ranking lies elsewhere. If we consider not the mere position in the ranking, but the absolute values of the average quality that respondents assign to the individual journals, we see that there is not a lot of variation between the perceived quality of the top 10 journals: it ranges from 4.64 (Nous, Philosophy & Phenomenological Research) to 4.16 (Philosophical Studies), less than 0.5 point on a Likert scale ranging from 1 to 5, so about the size of the affiliation bias discussed above. In fact, the top 5 differs only by slightly more than 0.1 point. Therefore, the survey-based ranking reveals a key insight: there is insufficient evidence to make definitive claims about quality disparities among the top journals in our field. Survey-based rankings may actually be better construed as measuring reputation rather than quality, and they come with quite a bit of uncertainty due to the fact that ultimately we estimate the views of the profession about these journals. So the main take-away is that rankings do not give us compelling reasons to distinguish, say, between Philosophical Review and Noûs in terms of perceived quality.

A slightly speculative way to make this claim more tangible is as follows. The journals that respondents had to rank do not represent the whole spectrum of philosophy journals. Journals at the bottom of our ranking (such as Metaphilosophy and Philosophia) are still respectable in the profession. Had respondents ranked all philosophy journals (or a sufficiently large representative selection of all philosophy journals), then journals could have been “tiered” in four groups (A, B, C, and D) in ways that are fairly standard in many fields: the top 10 percentile is tier A, the next 25 percentile is B, the next 40 percentile is C, and the lowest 25 percentile is D.

We can assign tiers if we assume – this is fairly big if indeed – that perceived journal quality in our field is distributed the way it is distributed in other fields; for if that is true, we can simply associate average quality to specific tiers. Following Currie and Pandher (2011), who cover a very wide selection of journals in financial economics, journals with average quality 3.70–5.00 are then in tier A, 3.10–3.70 in tier B, 2.30–3.10 in tier C, and below 2.30 in tier D. Map** this on to the survey-based ranking leads to the first 12 journals assigned to tier A, journals ranked 13–26 are in B, and all remaining journals except the lowest ranked journal are in C.

In the end, however, the answer to the question of what is “surprising” about the results is that our meta-ranking, rather than our survey-based ranking, may prove most relevant to the philosophical community. With a much lower correlation with Leiter’s ranking as well as with our own survey-based ranking (about 0.85, p < 0.001), the meta-ranking is really a different construct of journal quality or impact. Despite the many drawbacks of journal rankings, a meta-ranking is much less prone to be influenced by bias; the research reported in this paper may therefore help the project of mitigating bias in our profession (De Cruz, 2018; Saul, 2012). But to make that work, further meta-rankings should be developed for a much wider range of journals and subfields of philosophy, and surveys should cover a much larger variety of philosophers from subdisciplines (and be more diverse on other relevant dimensions just as well). Hopefully, this paper facilitates such work.

4.2 Limitations

Several limitations warrant acknowledgment. First: an important limitation is the sole focus on what is often called the “Western” tradition of philosophy. While the journals that appear in the rankings do publish work in African, Asian, and other traditions, such work is rare, and may still be criticized for ultimately being construed through Western eyes (Hidayat, 2000). Extending the methodologies to a broader range of journals should be straightforward, though.

Second and relatedly: the focus of the present paper is on Anglophone philosophy. Important philosophy journals (in the “Western” tradition) such as Revue internationale de philosophie and Deutsche Zeitschrift für Philosophie are, therefore, left out, as are multi-lingual journals such as Revista Portuguesa de Filosofia. Here, too, it should in principle be easy to extend our methodology, but the sheer absence of non-English publications in two of the main databases and the unreliability of Google Scholar (in this respect) form a considerable obstacle.

Third: any user of rankings will have to take into account that develo** a ranking is best seen as an attempt to estimate the quality of a journal on the basis of raw and never fully reliable data. We approximate the views held in the profession by focusing on those members of our profession that published in a number of preselected journals in the year before data collection; and we approximate, again, the views of these amply one thousand philosophers by studying survey responses of 35% of them. This is a good response rate, and the estimation techniques are standard methodology, but the results should be interpreted with care, among others, by realizing that the estimates reported here come with uncertainty. While in the past the uncertainty inherent in journal rankings was hardly ever mentioned, a new line of research in (primarily) economics attempts to develop accurate measures of ranking uncertainty (Lyhagen & Ahlgren, 2020; Mogstad et al., 2022). The current state of research does not allow us to adopt a definite stance on what the right measures are, and that is why these statistics are not included. Future journal rankings in philosophy will be able to take these insights into account. But among the reason for reporting various aggregate rankings (in the meta-ranking section) as well as separate rankings for subfields (in the survey-based ranking section) is that they illustrate the impact that small changes in design and sampling will have on the ultimate ranking one obtains. For instance, we may find it odd that Philosophers’ Imprint obtains a ranking below Inquiry even though it scores higher on all rankings reported in Table 1. This is a consequence of including a variety of h-index like metrics (not reported in Table 1) in the aggregation, on which these journals score quite differently.

Fourth: focusing on journal quality suggests a commitment to the view that journals are the primary outlet for philosophical work. It does not need to be that way. A staggering 30,000 papers on Covid-19 were published outside journals, on preprint servers (Triggle et al., 2022), and this trend can be witnessed in a large variety of disciplines. Whether our field is better served with or without journals is a question we must leave unanswered here, though.

4.3 Criticism

The bibliometric literature distinguishes between objective and subjective approaches to ranking journals. Rankings following the objective approach are based on publication data of journals, such as citation indices, citation impact scores, SSRN downloads, Google Scholar citations, and so forth (Law & Van Der Veen, 2008). For philosophy, objective journal rankings are largely unexplored territory. The meta-ranking is an attempt to construe one. The subjective approach, by contrast, uses the assessments of professionals or peers working in the field. In early bibliometric research, assessments were solicited from department chairs or other alleged experts, but nowadays the more common method is to focus on researchers who are active in the field at the moment of conducting the survey (Currie & Pandher, 2011). That is the methodology underlying the survey-based ranking.

Objective and subjective approaches to journal rankings can both be criticized. Objective measures can suffer from self-citation bias arising when a journal explicitly or tacitly encourages authors to cite articles that have appeared in the journal itself (Giri & Chaudhuri, 2021; Shehatta & Al-Rubaish, 2019). Research has shown that journals run by for-profit publishers, with lower impact factors, published in less prominent geographical areas of the academic community, and younger in age, are more prone to engaging in self-citation practices (Siler & Larivière, 2022). There is also evidence of “cartels” of mutually citing journals (Perez et al., 2019). It has also been pointed out that objective measures are often published without sufficient attention to the statistical reliability of the techniques used to derive the ranking, and that this results in overblown and/or unjustified applications of the rankings (Lyhagen & Ahlgren, 2020; Metze & Borges da Silva, 2022; Mogstad et al., 2022).

Survey-based rankings may suffer from all of the usual drawbacks of using questionnaires. This includes the representativeness of the samples, which are often small and atypical. Respondents may suffer from a variety of biases (fatigue bias, social desirability bias, etc.), may not care to give very considered answers to the questions asked, and may pretend to possess knowledge and insights on journals that they do not have. Participants were asked to give their judgment of the quality of 29 journals. But how many articles in a given journal must a philosopher have read to come up with a judgment that is based solely on their own views, and not on the views of others? The average scientist reads 22 scholarly articles per month, spending about half an hour on each article (Van Noorden, 2014). It is unlikely that this figure accurately represents reading habits in philosophy. How many Philosophical Review papers has the median respondent read over the last few years to be so sure that it merits a 5 on the Likert scale? It is also questionable whether researchers actually differentiate between journals. Anecdotal evidence suggests that professional philosophers have less than accurate memories for the journals in which particular articles were published.

As Table 4 shows, the survey-based ranking is quite close to Leiter’s ranking, and quite different from the meta-ranking, which suggest that the two rankings really estimate two different constructs: the quality of journals as it is perceived by professional philosophers, and the quality of journals as a latent construct that depends on citations. It is important to further examine the question of whether surveys retrieve information about actual judgments about the journal quality based on familiarity with work published in these journals. That is to say, when philosophers are asked to assess the quality of a journal, their response might primarily reflect their perception of the journal’s reputation within the academic community. If these views reflect prejudice and bias, a ranking based on citations may be preferable.

But citation-based rankings have received a great deal of criticism just as well. There is, for instance, significant criticism surrounding the formal and statistical properties of various metrics used in journal rankings. At a very fundamental level, Csató (2019) has proved an impossibility theorem that no ranking of journals satisfies all intuitive axioms that rankings should satisfy. Setting such formal concerns aside, another fundamental issue centers round the motivations researchers have to cite each other’s research. Generally, the view that underlies citation-based journal rankings is that researchers cite precisely those sources on which they base their contributions, by way of intellectual acknowledgement (Garfield & Merton, 1979). In empirical fields, this happens mostly in the literature review section of the paper, and the relatively low impact factors of philosophy journals may partly be explained by citation practices that do not follow this model. However, research suggests that citation motivation is a nuanced and multifaceted phenomenon (Bornmann & Daniel, 2008). Additionally, there is little justification for assuming that the reference section of an academic article provides a comprehensive and accurate representation of the work upon which the reported research is built (Aksnes et al., 2019). Reference sections may rather be seen as the result of strategic decisions (Śpiewanowski & Talavera, 2021), and betray sexist and racist attitudes (Davies et al., 2021).

Ample criticism has been directed at what is arguably the oldest and most well-known metric, the Journal Impact actor (JIF). Critics argue that the JIF’s reliance on the mean (average) instead of the median has resulted in an overemphasis on outliers, neglecting the fact that citation distributions often exhibit skewness (Kiesslich et al., 2020). This may well be the most often voiced criticism. A recent systematic survey showed that of a sample of 84 academic publications devoted to the topic, more than 65% criticize the JIF for failing to capture skewness (and also for being an inadequate measure of quality of individual researchers and individual articles) (Mech et al., 2020). This phenomenon is likely relevant in our field as well, even though this has not been systematically studied. To illustrate this phenomenon, consider that about 75% of all articles published in Science in 2015 and 2016 had a number of citations below the JIF value of 2015, which was 38; the most cited article in Science from that range was cited 694 times (Larivière et al., 2016). As Osterloh and Frey (2020) aptly write, this leads to a situation in which “[t]hree quarters of authors benefit from the minority of authors with many citations.” Figures for Nature and PLOS ONE are quite similar.

Another criticism of the JIF and other metrics is that the emphasis on citations within the past two years neglects the substantial variations in publication practices across different fields. This criticism is particularly pertinent in philosophy, where even “expedited” review processes can extend for over a year from submission to online publication. More generally, this is a question of how broad we want to construe the potential citation pool. Typically, the citation pool of a journal such as Science includes a much larger variety of journals than, say, Synthese. For indeed, Science publishes work from almost any field, while Synthese publishes only philosophy. The consequence of this is, however, that comparing the impact of journals solely on the basis of JIF may lead to counterintuitive results. To illustrate, the Journal of Business Ethics counts among the higher-ranking journals publishing philosophy. But as this journal mostly publishes theoretical and empirical work in the field of business and management (with vastly different citation practices), its 2021 JIF amounts to 6.331. Compare this to a 2021 JIF of 1.595 for Synthese. In other words, cross-disciplinary comparisons are not adequately facilitated by the JIF, and intradisciplinary comparisons become difficult where philosophy journals also publish non-philosophy work.

As mentioned in the beginning of this paper, work on rankings was initiated by Garfield (1955), who developed the JIF to aid librarians in making decisions about journal subscriptions. Since then, numerous alternatives have been proposed. The meta-ranking incorporated rankings based on metrics such as the Scimago Journal Rank, CiteScore, and the h-index. Notably, Brian Leiter also proposed the use of the Condorcet method. Most of these metrics are considered as substitutes for the JIF. However, it remains debatable to what extent these alternatives effectively address the inherent problems associated with the JIF. The Scimago Journal Rank privileges prestigious journals. The Eigenfactor cannot compare across disciplines. The h-index, developed by Hirsch (2005), fails to consider citations beyond the minimum threshold required to achieve a specific level h. Additionally, it tends to favor older and more established journals, while it does not effectively facilitate meaningful cross-disciplinary comparisons, and it privileges fields in which references are relatively young, unlike philosophy in which the average “age” of a reference may be about 40 years (Ferrara & Bonaccorsi, 2016). An average humanities paper has less than one citation in 10 years, as opposed to 40 citations in 10 years for biomedical research (Aksnes et al., 2019). The fact that the h-index is not normalized (adjusted to the relevant discipline) is, therefore seen as a significant obstacle. Another feature of the h-index is that it is sensitive to the number of articles a journal publishes per year. Harzing and van der Wal (2009) give the example of two well-known economics journals, one “small” journal publishing 15–20 highly cited papers, and one “big” journal with 160–170 not very highly cited papers. The “big” journal ends up with the highest h-index, which, according to the authors, accurately reflects the fact that this journal makes a “more substantial contribution to the field of economics” (Harzing & van der Wal, 2009, p. 44). Yet they also acknowledge that when it is one’s goal to evaluate individual economists, a publication in the “small” journal should be assigned “higher importance” (Harzing & van der Wal, 2009, p. 44). This is clearly of considerable relevance to philosophy, where the total annual output of some journals may equal the monthly output of others: the h-index of a journal must not be used to evaluate individual philosophers.

It is also important to point out that the quality of the databases has been criticized, for instance because of missing, duplicate, or incorrect citations, and (specifically for Google Scholar) for breadth of coverage (see Waltman, 2016 for a review). For our field, however, Google Scholar retrieves a significantly larger number of citations than Web of Science (Wildgaard, 2015). Philosophy shares this characteristic with the social sciences and humanities, which often have less prominence on the Web of Science due to their more national (non-English) orientation and relative prevalence of books, which may not be accurately covered by the Web of Science (Nederhof, 2006).

This is not to say that no further alternatives exist to assess journal quality. Various qualitative approaches have emerged to assess journal quality, encompassing factors such as the editorial process, peer review, publication charges, editorial board composition (Crookes et al., 2010). Moreover, the citation pool can be expanded to include articles published further in the past, typically ranging from two to five years. Metrics such as the total number of citations or article downloads have also been suggested to evaluate impact. Altmetrics, which encompasses social media and non-academic sources, can be used to gauge broader societal impact. Another measure involves assessing the quality of a journal based on the mean h-index of its editors. Regardless of the strengths of these alternatives, however, it is crucial to acknowledge that their success ultimately hinges on how we choose to use them.

4.4 Caution

So how should we use these rankings? The influential Leiden Manifesto (Hicks et al., 2015) gives some guidance here. Specifically relevant to our field is the recommendation to protect excellence in “locally relevant” research and to account for variation by field in publication and citation data. Philosophy is highly diverse when it comes to methods and traditions, but methods and traditions are unevenly distributed across journals. The background against which moral and political philosophy work is published in the highest-ranking general philosophy journals is overwhelmingly US centered, and to the extent that non-US institutions incentivize philosophers to publish in high-ranking journals, their involvement with domestic and more locally relevant questions will decrease. Philosophers are not alone in this respect (Bankovsky, 2019; Hojnik, 2021; López Piñeiro & Hicks, 2015).

The San Francisco Declaration on Research Assessment (DORA), which emerged from the 2012 meeting of the American Society for Cell Biology and has gained widespread acceptance among academics, universities, and research councils globally, urges researchers to refrain from using the Journal Impact Factor (JIF) as “a surrogate measure of the quality of individual research articles, to assess an individual scientist’s contributions, or in hiring, promotion, or funding decisions” (Alberts, 2013). And according to the “Statement on good practice in the evaluation of researchers and research programmes by three national Academies—Académie des sciences, Leopoldina and Royal Society,” journal impact factors “should not be considered in evaluating research outputs” (Statement, 2017). This may go too far if it extends to other forms of ranking journals than the JIF. But the cautious attitude underlying these statements should have our full endorsement.

So, while surveys and citations have value, journal quality surely involves a broader spectrum of factors. Quality is not solely determined by quantitative measures, but also by editorial board composition, rigorous academic standards, the integrity of the peer review process, among others. But what makes a journal a good philosophy journal was not the question this paper set out to answer.

References

Aksnes, D. W., Langfeldt, L., & Wouters, P. (2019). Citations, citation indicators, and research quality: An overview of basic concepts and theories. SAGE Open. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244019829575

Alberts, B. (2013). Impact factor distortions. Science, 340(6134), 787. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1240319

Araújo, C. (2019). Quatorze anos de desigualdade: mulheres na carreira acadêmica de Filosofia no Brasil entre 2004 e 2017. Cadernos De Filosofia Alemã: Crítica e Modernidade, 24(1), 13–33. https://doi.org/10.11606/issn.2318-9800.v24i1p13-33

Ávila Cañamares, I. (2020). Mujeres y filosofía. Ideas y Valores, 69(173), 9–36. https://doi.org/10.15446/ideasyvalores.v69n173.78354

Bankovsky, M. (2019). No proxy for quality: Why journal rankings in political science are problematic for political theory research. Australian Journal of Political Science, 54(3), 301–317. https://doi.org/10.1080/10361146.2019.1609412

Bornmann, L., Butz, A., & Wohlrabe, K. (2018). What are the top five journals in economics? A new meta-ranking. Applied Economics, 50(6), 659–675. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2017.1332753

Bornmann, L., & Daniel, H. D. (2008). What do citation counts measure? A review of studies on citing behavior. Journal of Documentation, 64(1), 45–80. https://doi.org/10.1108/00220410810844150

Bourget, D., & Chalmers, D. J. (2014). What do philosophers believe? Philosophical Studies, 170(3), 465–500. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-013-0259-7

Conklin, S. L., Nekrasov, M., & West, J. (2023). Where are the women. European Journal of Analytic Philosophy, 19(1), SI4-48. https://doi.org/10.31820/ejap.19.1.3

Crookes, P. A., Reis, S. L., & Jones, S. C. (2010). The development of a ranking tool for refereed journals in which nursing and midwifery researchers publish their work. Nurse Education Today, 30(5), 420–427. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2009.09.016

Csató, L. (2019). Journal ranking should depend on the level of aggregation. Journal of Informetrics, 13(4), 2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2019.100975

Currie, R. R., & Pandher, G. S. (2011). Finance journal rankings and tiers: An Active Scholar Assessment methodology. Journal of Banking & Finance, 35(1), 7–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2010.07.034

Davies, S. W., Putnam, H. M., Ainsworth, T., Baum, J. K., Bove, C. B., Crosby, S. C., Côté, I. M., Duplouy, A., Fulweiler, R. W., Griffin, A. J., Hanley, T. C., Hill, T., Humanes, A., Mangubhai, S., Metaxas, A., Parker, L. M., Rivera, H. E., Silbiger, N. J., Smith, N. S., ... Bates, A. E. (2021). Promoting inclusive metrics of success and impact to dismantle a discriminatory reward system in science. PLOS Biology, 19(6), e3001282. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3001282

De Cruz, H. (2018). Prestige bias: An obstacle to a just academic philosophy. Ergo: an Open Access Journal of Philosophy, 5, 259–287. https://doi.org/10.3998/ergo.12405314.0005.010

Demarest, H., Robertson, S., Haggard, M., Martin-Seaver, M., & Bickel, J. (2017). Similarity and enjoyment: Predicting continuation for women in philosophy. Analysis, 77(3), 525–541. https://doi.org/10.1093/analys/anx098

Dobbs, C. (2020). Evidence supporting pre-university effects hypotheses of women’s underrepresentation in philosophy. Hypatia, 32(4), 940–945. https://doi.org/10.1111/hypa.12356

Ferrara, A., & Bonaccorsi, A. (2016). How robust is journal rating in Humanities and Social Sciences? Evidence from a large-scale, multi-method exercise. Research Evaluation, 25(3), 279–291. https://doi.org/10.1093/reseval/rvv048

Garfield, E., & Merton, R. K. (1979). Citation indexing: Its theory and application in science, technology, and humanities (Vol. 8). Wiley.

Garfield, E. (1955). Citation indexes for science: A new dimension in documentation through association of ideas. Science, 122(3159), 108–111. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.122.3159.108

Giri, R., & Chaudhuri, S. K. (2021). Ranking journals through the lens of active visibility. Scientometrics, 126(3), 2189–2208. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-020-03850-6

Harzing, A.-W., & van der Wal, R. (2009). A Google Scholar h-index for journals: An alternative metric to measure journal impact in economics and business. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 60(1), 41–46. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.20953

Haslanger, S. (2008). Changing the ideology and culture of philosophy: Not by reason (alone). Hypatia, 23(2), 210–223. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1527-2001.2008.tb01195.x

Hassoun, N., Conklin, S., Nekrasov, M., & West, J. (2022). The past 110 years: Historical data on the underrepresentation of women in philosophy journals. Ethics, 132(3), 680–729. https://doi.org/10.1086/718075

Hicks, D., Wouters, P., Waltman, L., de Rijcke, S., & Rafols, I. (2015). Bibliometrics: The Leiden Manifesto for research metrics. Nature, 520(7548), 429–431. https://doi.org/10.1038/520429a

Hidayat, F. (2000). On the struggle for recognition of Southeast Asian and regional philosophy. Prajñā Vihāra, 16(2), 35–52.

Hirsch, J. E. (2005). An index to quantify an individual’s scientific research output. PNAS, 102(46), 16569–16572. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0507655102

Hojnik, J. (2021). What shall I compare thee to? Legal journals, impact, citation and peer rankings. Legal Studies, 41(2), 252–275. https://doi.org/10.1017/lst.2020.43

Iliadi, S., Theologou, K., & Stelios, S. (2020). Is the lack of women in philosophy a universal phenomenon? Exploring women’s representation in Greek Departments of Philosophy. Hypatia, 33(4), 700–716. https://doi.org/10.1111/hypa.12443

Kiesslich, T., Beyreis, M., Zimmermann, G., & Traweger, A. (2020). Citation inequality and the journal impact factor: Median, mean, (does it) matter? Scientometrics, 126(2), 1249–1269. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-020-03812-y

Larivière, V., Kiermer, V., MacCallum, C. J., McNutt, M., Patterson, M., Pulverer, B., Swaminathan, S., Taylor, S., & Curry, S. (2016). A simple proposal for the publication of journal citation distributions. bioRxiv, 062109. https://doi.org/10.1101/062109

Law, R., & Van Der Veen, R. (2008). The popularity of prestigious hospitality journals: A Google Scholar approach. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 20, 113–125. https://doi.org/10.1177/1096348019838028

López Piñeiro, C., & Hicks, D. (2015). Reception of Spanish sociology by domestic and foreign audiences differs and has consequences for evaluation. Research Evaluation, 24(1), 78–89. https://doi.org/10.1093/reseval/rvu030

Lyhagen, J., & Ahlgren, P. (2020). Uncertainty and the ranking of economics journals. Scientometrics, 125(3), 2545–2560. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-020-03681-5

Mech, E., Ahmed, M. M., Tamale, E., Holek, M., Li, G., & Thabane, L. (2020). Evaluating journal impact factor: A systematic survey of the pros and cons, and overview of alternative measures. Journal of Venomous Animals and Toxins including Tropical Diseases. https://doi.org/10.1590/1678-9199-jvatitd-2019-0082

Merllié, D. (2010). Un « périmètre de scientificité » pour les « produisants ». Le nouveau classement des revues de philosophie par l’aeres. Revue Philosophique De La France Et De L’étranger, 135(4), 495–507. https://doi.org/10.3917/rphi.104.0495

Metze, K., & Borges da Silva, F. A. (2022). Ranking of journals by journal impact factors is not exact and may provoke misleading conclusions. Journal of Clinical Pathology. https://doi.org/10.1136/jclinpath-2021-208051

Mogstad, M., Romano, J., Shaikh, A., & Wilhelm, D. (2022). Statistical uncertainty in the ranking of journals and universities. AEA Papers and Proceedings, 112, 630–634. https://doi.org/10.1257/pandp.20221064

Nederhof, A. J. (2006). Bibliometric monitoring of research performance in the Social Sciences and the Humanities: A review. Scientometrics, 66(1), 81–100. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-006-0007-2

Noichl, M. (2021). Modeling the structure of recent philosophy. Synthese, 198(6), 5089–5100. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-019-02390-8

Osterloh, M., & Frey, B. S. (2020). How to avoid borrowed plumes in academia. Research Policy. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2019.103831

Perez, O., Bar-Ilan, J., Cohen, R., & Schreiber, N. (2019). The network of law reviews: Citation cartels, scientific communities, and journal rankings. The Modern Law Review, 82(2), 240–268. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2230.12405

Peters, U., Honeycutt, N., De Block, A., & Jussim, L. (2020). Ideological diversity, hostility, and discrimination in philosophy. Philosophical Psychology, 33(4), 511–548. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515089.2020.1743257

Saul, J. (2012). Ranking exercises in philosophy and implicit bias. Journal of Social Philosophy, 43, 256–273. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9833.2012.01564.x

Schwitzgebel, E., & Jennings, C. D. (2017). Women in philosophy: Quantitative analyses of specialization, prevalence, visibility, and generational change. Public Affairs Quarterly, 31(2), 83–105. https://doi.org/10.2307/44732784

Schwitzgebel, E., Bright, L. K., Jennings, C. D., Thompson, M., & Winsberg, E. (2021). The racial, ethnic, and gender diversity of philosophy students and faculty in the United States: Recent data from several sources. The Philosopher’s Magazine, 93, 71.

Seiler, C., & Wohlrabe, K. (2014). How robust are journal rankings based on the impact factor? Evidence from the economic sciences. Journal of Informetrics, 8(4), 904–911. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2014.09.001

Shehatta, I., & Al-Rubaish, A. M. (2019). Impact of country self-citations on bibliometric indicators and ranking of most productive countries. Scientometrics, 120(2), 775–791. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-019-03139-3

Siler, K., & Larivière, V. (2022). Who games metrics and rankings? Institutional niches and journal impact factor inflation. Research Policy. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2022.104608

Śpiewanowski, P., & Talavera, O. (2021). Journal rankings and publication strategy. Scientometrics, 126(4), 3227–3242. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-021-03891-5

Statement. (2017). Statement by three national academies (Académie des Sciences, Leopoldina and Royal Society) on good practice in the evaluation of researchers and research programmes.

Stekeler-Weithofer, P. (2010). Publikationsverhalten in der Philosophie. Philosophische Rundschau, 57(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1628/003181510791058902

Subochev, A., Aleskerov, F., & Pislyakov, V. (2018). Ranking journals using social choice theory methods: A novel approach in bibliometrics. Journal of Informetrics, 12(2), 416–429. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2018.03.001

Triggle, C. R., MacDonald, R., Triggle, D. J., & Grierson, D. (2022). Requiem for impact factors and high publication charges. Accountability in Research, 29(3), 133–164. https://doi.org/10.1080/08989621.2021.1909481

van Eersel, G. G., Koppenol-Gonzalez, G. V., & Reiss, J. (2019). Extrapolation of experimental results through analogical reasoning from latent classes. Philosophy of Science, 86(2), 219–235. https://doi.org/10.1086/701956

Van Noorden, R. (2014). Scientists may be reaching a peak in reading habits. Nature. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature.2014.14658

Walters, W. H. (2017). Citation-based journal rankings: Key questions, metrics, and data sources. IEEE Access, 5, 22036–22053. https://doi.org/10.1109/access.2017.2761400

Waltman, L. (2016). A review of the literature on citation impact indicators. Journal of Informetrics, 10(2), 365–391. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2016.02.007

Wildgaard, L. (2015). A comparison of 17 author-level bibliometric indicators for researchers in Astronomy, Environmental Science, Philosophy and Public Health in Web of Science and Google Scholar. Scientometrics, 104(3), 873–906. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-015-1608-4

Acknowledgements

This paper was presented in the EXTRA.7 Research Colloquium (Bochum, February 2021). I would like to thank the audience collectively, and Joachim Horvath in particular. Special thanks are due to Castor Comploj for meticulous research assistance.

Funding

Funding was provided by NWO (Grant No. 360-20-380).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

de Bruin, B. Ranking philosophy journals: a meta-ranking and a new survey ranking. Synthese 202, 188 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-023-04342-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-023-04342-9