Abstract

The United Nations Development Programme Human Development Index (HDI) aggregates information on achievements in health, education and income. These achievements are given a weight of one-third each. These weights have been the subject of long-standing controversy, from the moment the HDI was released in 1990. Alternative weights reflecting stated citizen preferences are obtained in this paper using a discrete choice experiment involving a survey 2578 adult residents of the United Kingdom. Health is the most important achievement, with a mean weight of 0.428, followed by income and education, with mean weights of 0.292 and 0.280 respectively. Evidence in support of the view that HDI weights should vary among achievements and countries is provided, based on cluster and econometric analysis of the survey data.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The reference here to explicit weights is important and is based on recognising the difference between the HDI-dimension achievements and the indicators on which these achievements are based. They are the one-third weights assigned to the dimension achievements, which as shown below are based on statistical transformations of various indicators of health, education and income. As Ravallion (1997, 2011, 2012), Noorbakhsh (1998a, 1998b) and McGillivray and Noorbakhsh (2007) observe, the weights assigned to these indicators are the first partial derivative of each with respect to the HDI, which in turn are a function of both the explicit one-third weight of their transformations. The focus of this paper is on the determination of explicit weights.

These three methodological categories are based on those provided in Watson et al. (2019). Decancq and Lugo (2013) identify eight weighting approaches for multidimensional well-being indices and categorises such as data-driven, hybrid or normative. Decancq and Lugo categorise expert-based weights as normative, correlation-based weights as data-driven and stated-preference-based weights as hybrid as they are based both on data-driven and depend on some form of valuation of these achievements. Decancq and Lugo consider the HDI weighting scheme as normative for depending on ‘value judgements … [regarding trade-offs between dimensions] … and not on the actual distribution of the achievements’ (Decancq and Lugo, 2013, p. 9).

Deas et al. (2003) articulates several other concerns regarding expert-based dimension weights in the Index of Multiple Deprivation, which is used to assess deprivation levels in local authority wards in England.

See also Bellani et al. (2013), which observes “that whilst equal weighting may be practically unavoidable when constructing indices of welfare in the absence of information on weights” (p. 333) and that “it is an open empirical question as to whether equal weights are sufficiently close to people’s actual priorities” (p. 334).

Watson et al. (2018) include in this approach weights empirically inferred from the relationship between individual well-being and deprivation on the dimensions. Schokkaert (2007), Anand et al. (2009), Fleurbaey et al. (2009), Haisken-DeNew and Sinning (2010), Bellani (2013) and Bellani et al. (2013) derive weights using this approach. Decancq and Lugo (2013) refer to these weights as hedonic, but like stated-preference weights they fall under its hybrid classification, and discuss drawbacks of them.

See Balestra et al. (2018) for a survey of the relevant literature, which has mainly focussed on self-assessed well-being. Balestra et al. also derives weights, but using a scaling-based method instead of a DCE. Bellani (2013) and Bellani et al. (2013) also use scaling-based weighting methods. They are criticised for not requiring people to make choices and confront trade-offs between the dimensions considered. On this point in general, Drummond et al., (2015, p. 68) comment that: “The advantage of choice-based methods is that choosing, unlike scaling, is a natural human task at which we all have considerable experience, and furthermore it is observable and verifiable.”.

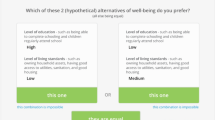

This sample comprised 1022 microeconomics students in Belgium, Colombia, Ethiopia and the United States. In addition to involving a representative sample, the DCE introduced below differs from the DCE in Decancq and Watson (2019) in other fundamental ways, including the DCE method used and the wording of the three HDI dimensions included in the DCE. Acknowledging the non-representativeness of their sample, the authors note that their study “should therefore be read as a proof-of-concept of a DCE-based method to set the parameters of a generalized HDI, rather than a definitive answer about the values of these parameters” (p. 11).

An anonymous reviewer of this paper correctly pointed out that its analysis relies on the HDI, which was an original contribution of the UNDP and not this paper. As such, as the reviewer notes, our analysis and the HDI cannot be considered independently.

The natural zeros and aspirational targets are set by the UNDP. Details are in UNDP (2019a). Since many countries exceed the aspirational targets in education and income, and achievements are capped at unity, achievements in these dimensions are not (quite) a linear transformation of the indicators on which they are based.

This method and software have been used for research into people’s preferences in a wide range of areas; for brief surveys, see Wijland et al. (2016) and Sullivan et al. (2020a). In the development-aid literature, PAPRIKA and 1000minds have been used to investigate the public’s preferences with respect to the allocation of official development assistance by the governments of the UK (Feeny et al., 2019) and New Zealand (Cunningham et al., 2017) and the types of countries to receive development assistance funds from non-government organisations (Hansen et al., 2014).

Excluding 825 individuals from the sample is an exclusion rate of 32%. This is not large by the standards of other studies that exclude sample participants for providing inconsistent responses. For example, Sullivan et al (2020b) report an exclusion rate of 42%.

These rejections were also provided from the Hotelling T2 statistic for multivariate hypothesis testing. This statistic is based on the square of the t-statistic and is evaluated using an F test.

Decancq and Watson (2019) assign by far the highest weight to income, in all four sub-samples used in their study. They assign a marginaly higher weight to health than income. While their results are informative, one needs to keep in mind Decancq and Watson’s caveat that their study is a proof-of-concept of a DCE-based method to assign weights to a HDI, and not a definitive answer about the values of the index’s weights.

These tests were obtained from mean of differences from the data in Table 2, and for the period 1999–2018. The tests were evaluated as \(t= \overline{d }/\left({s}_{d}/\sqrt{n}\right)\) where \(\overline{d }\) in this instance is the mean of the differences between the two HDIs and \({s}_{d}\) is the standard deviation of the differences. The t-statistic for the 1999–2018 sample is 21.63.

References

Anand, P., Hunter, G., Carter, I., Dowding, K., Guala, F., & van Hees, M. (2009). The development of capability indicators. Journal of Human Development and Capabilities, 10(1), 125–152.

Anand, S., & Sen, A. (1992). Human development index: Methodology and measurement. Background paper for the Human Development Report 1993. UNDP.

Adler, M. D., Dolan, P., & Kavetsos, G. (2017). Would you choose to be happy? Tradeoffs between happiness and the other dimensions of life in a large population survey. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 139, 60–73.

Balestra, C., Boarini, R., & Tosetto, E. (2018). What matters most to people? Evidence from the OECD better life index users’ esponses. Social Indicators Research, 136, 907–930.

Bellani, L. (2013). Multidimensional indices of deprivation: The introduction of reference groups weights. Journal of Economic Inequality, 11(4), 495–515.

Bellani, L., Hunter, G., & Anand, P. (2013). Multidimensional welfare: Do groups vary in their priorities and behaviours? Fiscal Studies, 34(3), 333–354.

Benjamin, D. J., Heffetz, O., Kimball, M. S., & Rees-Jones, A. (2012). What do you think would make you happier? What do you think you would choose? American Economic Review, 102(5), 2083–2110.

Cunningham, H., Knowles, S., & Hansen, P. (2017). Bilateral foreign aid: How important is aid effectiveness to people for choosing countries to support? Applied Economics Letters, 24(5), 306–310.

Chowdhury, S., & Squire, L. (2006). Setting weights for aggregate indices: An application to the commitment to development index and human development index. Journal of Development Studies, 42(5), 761–771.

Deas, I., Robson, B., Wong, C., & Bradford, M. (2003). Measuring neighbourhood deprivation: A critique of the index of multiple deprivation. Environment and Planning, C, 21, 883–904.

Decancq, K., & Lugo, A. (2013). Weights in multidimensional indices of wellbeing: An overview. Econometric Reviews, 32(1), 7–34.

Decancq, K., & Watson, V. (2019). Eliciting weights for the human development index with a discrete choice experiment. University of Antwerp and University of Aberdeen, mimeo.

Drummond, M. F., Sculpher, M. J., Stoddart, G. L., & Torrance, G. W. (2015). Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes. Fourth Edition. Oxford University Press.

Eva, B. (2019). Principles of indifference. The Journal of Philosophy, 116(7), 390–411.

Feeny, S., Hansen, P., Knowles, S., McGillivray, M., & Ombler, F. (2019). Donor motives, public preferences and the allocation of UK foreign aid: A discrete choice experiment approach. Review of World Economics, 155(3), 511–537.

Fleurbaey, M., Schokkaert, E., & Decancg, K. (2009). What good is happiness? CORE Discussion Papers 2009017, Université Catholique de Louvain, Center for Operations Research and Econometrics.

Foster, J. E., McGillivray, M., & Seth, S. (2013). Composite indices: Rank robustness, statistical association, and redundancy. Econometric Reviews, 32, 35–56.

Haisken-DeNew, J., & Sinning, M. (2010). Social deprivation of immigrants in Germany. Review of Income and Wealth, 56(4), 715–733.

Hansen, P., Kergozou, N., Knowles, S., & Thorsnes, P. (2014). Develo** countries in need: Which characteristics appeal most to people when donating money? Journal of Development Studies, 50(11), 1494–1509.

Hansen, P., & Ombler, F. (2008). A new method for scoring additive multi-attribute value models using pairwise rankings of alternatives. Journal of Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis, 15, 87–107.

Kelley, A. C. (1991). The human development index: Handle with care. Population and Development Review, 17(2), 315–324.

Keynes, J. M. (1921). A treatise on probability. Macmillan.

Lai, D. (2000). Temporal analysis of human development indicators: Principal component approach. Social Indicators Research, 51(3), 331–366.

McFadden, D. (1974). Conditional logit analysis of qualitative choice behaviour. In P. Zarembka (Ed.), Frontiers in econometrics (pp. 105–142). Academic Press.

McGillivray, M., & Noorbakhsh, F. (2007). Composite indices of human well-being: Past, present and future. In M. McGillivray (Ed.), Human well-being: Concept and measurement. Palgrave-Macmillan.

Nguefack-Tsague, G., Klasen, S., & Zucchini, W. (2011). On weighting the components of the human development index: A statistical justification. Journal of Human Development and Capabilities, 12(2), 183–202.

Noorbakhsh, F. (1998a). A modified human development index. World Development, 26(3), 517–528.

Noorbakhsh, F. (1998b). The human development index: Some technical issues and alternative indices. Journal of International Development, 10(5), 589–605.

Ogwang, T. (1994). The choice of principle variables for computing the human development index. World Development, 22(12), 2011–2014.

ONS. (2011). 2011 census: population estimates for the united kingdom. Office for National Statistics.

Permanyer, I. (2011). Assessing the robustness of composite indices rankings. Review of Income and Wealth, 57, 306–326.

Rao, B. V. V. (1991). Human development report 1990: Review and assessment. World Development, 19(10), 1451–1460.

Ravallion, M. (1997). Good and bad growth: The human development reports. World Development, 25(5), 631–638.

Ravallion, M. (2011). Mashup indices of development. The World Bank Research Observer, 27, 1–32.

Ravallion, M. (2012). Troubling tradeoffs in the human development index. Journal of Development Economics, 99(2), 201–209.

Schokkaert, E. (2007). Capabilities and satisfaction with life. Journal of Human Development, 8(3), 415–430.

Spath, H. (1980). Cluster analysis algorithms for data reduction and classification of objects. Ellis Horwood.

Srinivasan, T. N. (1994). Human development: A new paradigm or reinvention of the wheel? American Economic Review, Papers and Proceedings, 84(2), 238–243.

Stapleton, L. M., & Garrod, G. D. (2007). Kee** things simple: Why the human development index should not diverge from its equal weights assumption. Social Indicators Research, 84(2), 179–188.

Sullivan, T., Smith, J., Ombler, F., & Brayley-Morris, H. (2020a). Prioritizing the investigation of organized crime. Policing and Society, 30(3), 327–348.

Sullivan, T., Hansen, P., Ombler, F., Derrett, S., & Devlin, N. (2020b). A new tool for creating personal and Ssocial EQ-5D-5L value sets, including valuing ‘dead.’ Social Science and Medicine, 246(112707), 1–9.

UNDP. (1993). Human development report 1993. Oxford University Press.

UNDP. (2019a). Human development report 2019a. United Nations Development Programme.

UNDP. (2019b). Human development data (1990–2018). United Nations Development Programme.

Veenhoven, R. (1996). Happy life-expectancy. Social Indicators Research, 39(1), 1–58.

Watson, V., Dibben, C., Cox, M., Atherton, I., Sutton, M. and Ryan. M. (2019). Testing the Expert Based Weights Used in the UK’s Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) Against Three Preference-Based Methods. Social Indicators Research, 144, 1055–1074.

World Economic Forum. (2005). 2005 environmental sustainability index: Benchmarking national environmental stewardship. World Economic Forum.

Wijland, R., Hansen, P., & Gardezi, F. (2016). Mobile nudging: Youth engagement with banking apps. Journal of Financial Services Marketing, 21(1), 51–63.

Acknowledgements

The authors are most grateful for very helpful comments from three anonymous referees on an earlier draft of this paper. The usual disclaimer applies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

See Table 5.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

McGillivray, M., Feeny, S., Hansen, P. et al. What are Valid Weights for the Human Development Index? A Discrete Choice Experiment for the United Kingdom. Soc Indic Res 165, 679–694 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-022-03039-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-022-03039-9