Abstract

The present paper evaluates whether people in highly individualistic cultures have a lower propensity to commit homicides, using data from 70 countries. Several previous papers report a significant negative correlation between these two variables, but it is not well established whether the effect of culture on this form of violent crime is direct or indirect. We estimate a structural equation model that includes: (a) the possibility that either culture or institutions affect the homicide rate, (b) a link between individualism and institutions and (c) credible exogenous information used as an instrumental variable for individualism. Our results show that individualistic nations generate a more effective judicial system, which is mainly responsible for the variation in homicide rates across countries. That is, individualism affects homicides only indirectly through the quality of legal institutions. We also find that different types of institutions have a similar relation to individualism, however, the moderating effect on homicides is more pronounced for legal or political institutions than for economic institutions.

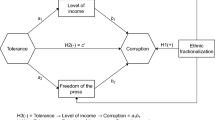

Source: Authors’ illustration

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Note that we use the term individualism-collectivism because it is a well-established in the academic literature (not only in economics) and it makes clear that we use Hofstede’s measure. Some leading authors in the field, such as Greif and Tabellini (2017), however, seem to have a certain reservation against this terminology and they refer to a corporative vs. kin-based organization of societies. The term individualistic-collectivist is reserved for the explicit reference to the value system of these societies. We try to explain, as good as possible, which values and attitudes are related to individualistic and collectivist societies in the Hofstede’s terminology and we advise those readers who feel uncomfortable with this expression to recall the corporative vs. kin-based terminology.

The PSTV has been applied in a growing number of papers that establish a link between historical disease prevalence and macro-level outcomes such as economic growth (Gorodnichenko and Roland 2017), income inequality and governmental redistribution (Nikolaev et al. 2017; Gründler and Köllner 2018), economic and political institutions (Nikolaev and Salahodjaev 2017; Thornhill and Fincher 2014), and innovation (Bennett and Nikolaev 2020).

A factor that complicates the econometric analysis considerably is the possibility that formal and informal institutions may co-evolve (Alesina and Giuliano 2015). For example, as a country maintains well-functioning and evermore solid (judicial or monetary) institutions, informal norms such as honesty may also change over time.

To implement the estimation of the SEM, we rely on Stata’s command sem.

The frequency of blood types is genetically transmitted through generations and thus highly persistent. The blood distance variable we use is calculated as the Mahalanobis distance of frequency of blood types A and B in each country relative to the frequency of blood types A and B in the UK because the British society is recognized as the most individualistic in the world.

Leishmanias, trypanosomes, malaria, schistosomes, filariae, leprosy, dengue, typhus, and tuberculosis.

Homicide data is available at: https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/data-and-analysis/crime-and-criminal-justice.html.

UNODC, International Classification of Crime for Statistical Purposes (ICCS): Version 1.0 (Vienna, 2015).

Using colonizer identity instead of legal origin as a control in the SEM produces very similar results.

The WEF data is available at: https://www.weforum.org/reports/the-global-competitiveness-report-2017-2018

In fact, the correlation between Kunčič’s political and legal institutions is almost perfect (0.94), their relation to economic institutions is somewhat lower (0.85).

References

Acemoglu, D., Johnson, S., & Robinson, J. (2001). The colonial origins of comparative development: An empirical investigation. American Economic Review, 91(5), 1369–1401.

Alesina, A., & Giuliano, G. (2015). Culture and institutions. Journal of Economic Literature, 53(4), 898–944.

Appel, R., Fratzl, J., McKay, R., & Stevens, C. (2014). Enron and the 12 steps of white-collar crime. International Journal of Business Governance and Ethics, 9(4), 381–405.

Becker, G. S. (1968). Crime and punishment: An economic approach. Journal of Political Economics, 76(2), 169–217.

Becker, S., Boeckh, K., Hainz, C., & Woessmann, L. (2016). The empire is dead, long live the empire! long-run persistence of trust and corruption in the bureaucracy. The Economic Journal, 126, 40–74.

Beilmann, M., Kööts-Ausmees, L., & Realo, A. (2018). The relationship between social capital and individualism-collectivism in Europe. Social Indicators Research, 137, 641–664.

Bellemare, M. F., & Wichman, C. J. (2020). Elasticities and the inverse hyperbolic sine transformation. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 82(1), 50–61.

Bennett, D. L., Faria, H. J., Gwartney, J. D., & Morales, D. R. (2016). Evaluating alternative measures of institutional protection of private property and their relative ability to predict economic development. Journal of Private Enterprise, 31, 57–78.

Bennett, D. L., Faria, H. J., Gwartney, J. D., & Morales, D. R. (2017). Economic institutions and comparative economic development: A post-colonial perspective. World Development, 96, 503–519.

Bennett, D. L., & Nikolaev, B. (2016). Factor endowments, the rule of law and structural inequality. Journal of Institutional Economics, 12(04), 773–795.

Bennett, D. L., & Nikolaev, B. (2020). The historical prevalence of infectious diseases and global innovation. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice: In Press.

Beugelsdijk, S., Maseland, R., & Hoorn, A. V. (2015). Are scores on Hofstede’s dimensions of national culture stable over time? A cohort analysis. Global Strategy Journal, 5, 223–240.

Binder, C. C. (2019). Redistribution and the individualism-collectivism dimension of culture. Social Indicators Research, 142, 1175–1192.

Bjørnskov, C. (2010). How does social trust lead to better governance? An attempt to separate electoral and bureaucratic mechanisms. Public Choice, 144, 323–346.

Bjørnskov, C. (2015). Does economic freedom really kill? On the association between ‘Neoliberal’ policies and homicide rates. European Journal of Political Economy, 37, 207–2019.

Blickle, G., Schlegel, A., Fassbender, P., & Klein, U. (2006). Some personality correlates of business white-collar crime. Applied Psychology, 55(2), 220–233.

Boettke, P. J., Coyne, C. J., & Leeson, P. T. (2008). Institutional stickiness and the new development economics. The American Journal of Economics and Sociology, 67, 331–358.

Caffaro, F., Ferraris, F., & Schmidt, S. (2014). Gender differences in the perception of honour killing in individualist versus collectivistic cultures: Comparison between Italy and Turkey. Sex Roles, 71, 296–318.

Chamlin, M. B., & Cochran, J. K. (2006). Economic inequality, legitimacy, and cross-national homicide rates. Homicide Studies, 10(4), 231–252.

Davidson, R., Dey, A., & Smith, A. (2015). Executives’ “Off-The-Job” behavior, corporate culture, and financial reporting risk. Journal of Financial Economics, 117(1), 5–28.

Detotto, C., & Otranto, E. (2010). Does crime affect economic growth? Kyklos, 63(3), 330–345.

Duggan, M. (2001). More guns, more crime. Journal of Political Economy, 109(5), 1086–1114.

Durkheim, E. (1957). Professional ethics and civic morals. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Eisner, M. (2003). Long-term historical trends in violent crime. Crime and Justice, 30, 83–142.

Elias, N. (1982). The civilizing process. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Fajnzylber, P., Lederman, D., & Loayza, N. (2002). What causes violent crime? European Economic Review, 46, 1323–1357.

Fincher, C. L., Thornhill, R., Murray, D. R., & Schaller, M. (2008). Pathogen prevalence predicts human cross-cultural variability in individualism/collectivism. Royal Society, 275, 1279–1285.

Gorodnichenko, Y., & Roland, R. (2017). Culture, institutions, and the wealth of nations. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 99(3), 402–416.

Greif, A. (1994). Cultural beliefs and the organization of society: A historical and theoretical reflection on collectivist and individualist societies. The Journal of Political Economy, 102(5), 912–950.

Greif, A., & Tabellini, G. (2017). The clan and the corporation: Sustaining cooperation in China and Europe. Journal of Comparative Economics, 45, 1–35.

Grosjean, P. (2014). A history of violence: The culture of honor and homicide in the US South. Journal of the European Economic Association, 12(5), 1285–1316.

Gründler, K., Köllner, S. (forthcoming). Culture, diversity, and the welfare state. Journal of Comparative Economics.

Gutmann, J., & Voigt, S. (2018). The rule of law: Measurement and deep roots. European Journal of Political Economy, 54, 68–82.

Hackman, J., & Hruschka, D. (2013). Fast life histories, not pathogens, account for state-level variation in homicide, child maltreatment, and family ties in the U.S. Evolution and Human Behavior, 34, 118–124.

Haney, C. (1982). Criminal justice and the nineteenth-century paradigm: The triumph of psychological individualism in the" Formative Era.". Law and Human Behavior, 6(3–4), 1991–225.

Hofstede, G. (1983). The cultural relativity of organizational practices and theories. Journal of International Business Studies, 14(2), 75–89.

Hofstede, G. (2011). Dimensionalizing cultures: The hofstede model in context. Online Readings in Psychology and Culture, 2(1), 8.

Hofstede Insights. (2018). Country Culture Tools. Retrieved from https://www.hofstede-insights.com/country-culture-tools/

Joo, H.-J. (2003). Crime and crime control. Social Indicators Research, 62, 239–263.

Klerman, D. M., Mahoney, P. G., Spamann, H., & Weinstein, M. I. (2011). Legal origin or colonial history? Journal of Legal Analysis, 3, 379–409.

Kunčič, A. (2014). Institutional quality dataset. Journal of Institutional Economics, 10(1), 135–161.

Kyriacou, A. (2016). Individualism–collectivism, governance and economic development. European Journal of Political Economy, 42, 91–104.

Lappi-Seppälä, T., Lehti, M. (2014). Cross-comparative perspectives on global homicide trends. In M. Tonry (Ed.), Why crime rates fall and why they don’t (pp. 135–230). Crime and justice: A review of research. https://doi.org/10.1086/677979.

Le, T., & Stockdale, G. (2005). Individualism, collectivism, and delinquency in Asian American adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 34(4), 681–691.

Levitt, S., & Miles, T. (2006). Economic contributions to the understanding of crime. Annual Review of Law and Social Science, 2, 147–164.

Licht, A., Goldschmidt, C., & Schwartz, S. (2007). Culture rules: The foundations of the rule of law and other norms of governance. Journal of Comparative Economics, 35, 659–688.

Mullings, R. (2018). Do institutions moderate globalization’s effect on growth? Journal of Institutional Economics, 4(1), 71–102.

Munck, G. L., & Verkuilen, J. (2002). Conceptualizing and measuring democracy: Evaluating alternative indices. Comparative Political Studies, 35(5), 5–34.

Nikolaev, B., Boudreaux, C., & Salahodjaev, R. (2017). Are individualistic societies less equal? Evidence from the parasite stress theory of values. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 138, 30–49.

Nikolaev, B., & Salahodjaev, R. (2017). Historical prevalence of infectious diseases, cultural values, and the origins of economic institutions. Kyklos, 70, 97–128.

Pitlik, H., & Rode, M. (2017). Individualistic values, institutional trust, and interventionist attitudes. Journal of Institutional Economics, 13(3), 575–598.

Rossow, I. (2001). Alcohol and homicide: a cross-cultural comparison of the relationship in 14 European countries. Addiction, 96, 77–92.

Sanyal, R. (2005). Determinants of bribery in international business: The cultural and economic factors. Journal of Business Ethics, 59(1–2), 139–145.

Schwartz, S. H. (2004). Map** and interpreting cultural differences around the world. In H. Vinken, J. Soeters, & P. Ester (Eds.), Comparing cultures: dimensions of culture in a comparative perspective. Brill: Leiden.

Seleim, A., & Bontis, N. (2009). The relationship between culture and corruption: a cross-national study. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 10(1), 165–184.

Small Arms Survey. (2007). Guns and the city. Cambridge: University Press.

Soares, R. (2004). Crime reporting as a measure of institutional development. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 52(4), 851–871.

Spencer, N., & Liu, Z. (2019). Victimization and life satisfaction: Evidence from a high crime country. Social Indicators Research, 144, 475–495.

Stock, J. H., Yogo, M. (2002). Testing for weak instruments in linear IV regression. Technical Working Paper 284, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, USA.

Taras, V., Steel, P., & Kirkman, B. L. (2012). Improving national cultural indices using a longitudinal meta-analysis of Hofstede’s dimensions. Journal of World Business, 47(3), 329–341.

Thome, H. (2001). Explaining long term trends in violent crime. Crime History and Societies, 5(2), 69–86.

Thornhill, R., & Fincher, C. L. (2011). Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, 366, 3466–3477.

Thornhill, R., & Fincher, C. L. (2014). The parasite-stress theory of values and sociality: Infectious disease, history and human values worldwide (1st ed.). Switzerland: Springer International Publishing.

Williamson, O. E. (2000). The new institutional economics: Taking stock, looking ahead. Journal of Economic Literature, 38(3), 595–613.

Yamen, A., Al Qudah, A., Badawi, A., Bani-Mustafa, A. (2017). The impact of national culture on financial crime: A cross country analysis. The 40th Annual Congress of the European Accounting Association.

Zheng, X., El Ghoul, S., Guedhami, O., & Kwok, C. (2013). Collectivism and corruption in bank lending. Journal of International Business Studies, 44(4), 363–390.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Further Details About the Data Set

The main limitation of our sample size comes from the availability of Hofstede’s individualism data. Table 7 confirms that the index is defined for only 70 countries and we adjust the remainder variables to this basic sample. The human capital index and the inequality variable present also present gaps but to avoid a further reduction of sample size we complement these two variables with highly correlated, similar indicators from different sources. To impute values for the human capital index we use the years of schooling from the UNDP, run a simple regression involving these two variables and then use the predicted values for countries where human capital is unavailable. The same procedure is applied with the Inequality and the Gini index from the WIID. Regarding the homicide rate, we maximize the number of countries in the sample by considering the average homicide rate between 2010 and 2015. Therewith, we lose fewer observations and maintain a sample with enough variation at all income and individualism levels. In fact, we observe that despite the extended period, the murder rate has little variability.

The most reliable measure for the number of weapons per country was found in the Small Arms Survey (2007), which includes both registered and unregistered weapons. Despite the temporal divergence to the rest of our data, two reasons justify the use of this information. First, the number of weapons in each country changes very little. Second, the time lag in the Guns variable mitigates a possible reverse causality problem since it would be possible that the amount of murders in a nation could lead people to buy more weapons for personal protection. Despite considerable econometric effort, principally exploiting difference-in-difference estimation in the context of region-specific regulatory changes, Levitt and Miles (2006) report that the literature found evidence for negative, positive and insignificant effects of gun possession on crime. Although we observe that the possession of guns has a positive sign, indicating that a higher incidence of weaponry in a nation implies a higher homicide rate, we caution the reader to interpret this effect as causal. For more elaborate studies, see Levitt and Miles (2006) or Duggan (2001).

Regarding the expected results for the remaining control variables in Eq. (2), which has the homicide rate as dependent variable, we expect positive signs for the estimated coefficients of economic inequality and alcohol, because drug consumption and greater involuntary, ascribed social inequality tend to increase criminal incidents (Chamlin and Cochran 2006). According to Rossow (2001), many criminal incidents, especially violent crimes occur under the influence of alcohol. Individuals in highly unequal countries may be more motivated to commit crimes, not because of the precarious condition in which they live, but rather due to a psychological impression of injustice as they compare the amount of their resources to those of other citizens. That is, we expect a positive coefficient for inequality. Note that the results were very similar when we used the Gini index as the measure of inequality. A positive effect is also expected for unemployment.

Furthermore, we expect negative effects for the variables of income and human capital. According to Gorodnichenko and Roland (2017), the more individualistic a population is, the greater its income and the better its education outcomes. These results would be in line with the work of Lappi-Seppälä and Lehti (2014), and Fajnzylber et al. (2002). Regarding the share of men, elderly, young, and rural in a country, we do not have any priors regarding its sign and significance. See Tables

6,

7 and

8.

Appendix 2: Additional Tables and Figures from Robustness Checks

See Figs. 5 and 6, Tables 9, 10 and 11.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zanchi, V.V., Ehrl, P. & Maciel, D.T.G.N. Direct and Indirect Effects of Individualism and Institutions on Homicides. Soc Indic Res 153, 1167–1195 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-020-02531-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-020-02531-4