Abstract

Comprehensive sexuality education (CSE) is instrumental in ensuring that young people have the knowledge and skills to make informed decisions and practice safer sex. Worryingly, CSE is often not available to adolescents and young with disabilities. The Breaking the Silence (BtS) approach to CSE was developed to address this gap and help equip educators to teach CSE to adolescents and young people with disabilities. The TSE-Q was designed to evaluate the effectiveness of the BtS approach and monitor changes in educators’ knowledge, skills, attitudes, self-confidence, and preparedness to teach CSE to young people with disabilities. The TSE-Q is aligned with an adapted version of the theory of planned behavior. This is a second validation study of the TSE-Q embedded within a feasibility study for the BtS approach. Fifty educators and support staff from two South African special schools for people with disability participated in a BtS training workshop and completed the TSE-Q before and after the workshop. Additionally, participants were asked to complete an adapted version of Rowe, Oxman, and O’Brien’s validity questionnaire probing content validity, face validity, and ease of use. Baseline data from the TSE-Q was evaluated for reliability, while the validity questionnaire and verbal feedback were used to assess validity. Most scales show good reliability, but knowledge-based scales have lower reliability due to their multidimensionality. The TSE-Q shows good face validity, content validity, and ease of use, but should be done on different days to any intervention/training. Overall, the TSE-Q is a robust questionnaire with good content coverage.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Adolescents and young people with disabilities have the same sexual and reproductive health (SRH) needs as their peers without disabilities. However, they are also at increased risk of adverse SRH outcomes and rights violations, including increased risk of HIV infection and experience of violence [1,2,3,4,5,6,7]. Recent evidence shows that the increased risk of exposure to HIV and violence follows into adulthood and holds a gendered dimension. Women with disabilities are twice as likely to experience intimate partner violence (IPV) and HIV infection as their peers without disabilities [3,4,5, 8,9,10]. The risk of IPV increases with the severity of the disability [9]. Exposure to violence also varies across different types of disabilities, with people with mental illnesses and intellectual disabilities being at particular risk [6].

Despite these increased SRH vulnerabilities, adolescents and young people with disabilities lack access to sexual reproductive health and rights (SRHR) services, including comprehensive sexuality education (CSE) in South Africa, where HIV and gender-based violence are endemic [10,11,12]. Worldwide, CSE is a cornerstone of efforts to equip adolescents and young people with the knowledge, attitudes, and skills to make informed decisions and practice safer sex [10, 13, 14]. Furthermore, program evaluations have shown that access to CSE effectively prevents risky sexual behavior and HIV infections. In contrast, abstinence-only or pro-sexuality education programs are ineffective at preventing HIV [14, 15]. However, research shows that adolescents and young people with disabilities lack access to CSE and do not have access to correct information about sexuality from their caregivers, parents, or peers [16,17,18,19,20,21].

Research with educators of learners with disabilities in Eastern and Southern Africa shows that these educators often feel ill-equipped to provide CSE in accessible formats to learners with disabilities. Educators may also hold negative attitudes about CSE or the intersection of disability and sexuality and may fear repercussions due to community norms around CSE, sexuality, and disability [22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29]. In response, the Breaking the Silence approach (BtS) to CSE was developed. BtS is aligned with the UN Technical Guidelines on sexuality education and focuses on educator training and development to change attitudes, improve self-efficacy, and develop skills to provide accessible CSE to learners with diverse disabilities [30,31,32]. The BtS approach to CSE offers a 3–4 day workshop-based training, where participants are exposed to legal and epidemiological information, universal design to learning, accommodation of learners with disabilities, development of CSE implementation guidelines, and practical skills for teaching CSE in accessible formats for diverse disabilities. Educators receive a Comprehensive Guide and 15 Lesson Plans with accessible resources and teaching tools to implement CSE after the workshops [33, 34].

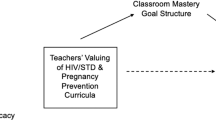

The Teacher Sexuality Education Questionnaire (TSE-Q) was developed to assess the impact of the BtS educator training on participants [35, 36]. The TSE-Q was initially designed and validated in 2013 [36]. Some of the scales and sets of questions were culturally adapted from pre-existing scales, while others were developed specifically to assess CSE delivery to learners with disabilities in South Africa [36]. The questionnaire is based on an adapted version of the theory of planned behavior (TPB) (Fig. 1). It includes a scale for CSE knowledge, attitudes and beliefs (disability, sexuality, and HIV), CSE teaching beliefs and behavior, perceived subjective norms, self-efficacy, and environmental conditions at the school (availability of material to teach CSE and linkage to SRHR services) [36, 37].

The original TSE-Q was reviewed and culturally adapted with educators in South Africa through formative validation, including focus group discussions and written reviews [36]. The questionnaire’s formative validation and reliability testing revealed that the teaching beliefs, behavior, and self-efficacy scales were robust. The sets of questions prompting environmental conditions, knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs about disability, sexuality, and HIV were not robust enough [36]. Since then, the BtS team has adjusted the disability, sexuality, HIV, and environmental conditions sets of questions and developed sets of questions related to CSE policy knowledge and confidence in CSE teaching skills. In 2021, the team tested the adapted TSE-Q before implementing two BtS training workshops [35]. This paper presents the results of the reliability and validity testing of the adjusted TSE-Q in South Africa.

Methods

Study Design

We conducted a validation study of the adapted version of the TSE-Q. This study was embedded in a feasibility study assessing the implementation and effectiveness of the Breaking the Silence CSE workshop training with two purposively selected special schools in South Africa [35]. The adapted TPB guided the development of the TSE-Q and the validation study [36, 37]. The adapted TPB postulates that individual behavior (e.g., teaching behavior) is determined by the intention to perform the behavior, having the necessary skills, and environmental conditions to execute the behavior [37]. In addition, the intention to perform a behavior is determined by knowledge and attitudes, self-efficacy, and perceived subjective norms (see Fig. 1). Hence, when assessing educators’ likelihood of implementing CSE, we need to evaluate their CSE teaching intention, skills, and environmental conditions under which they are supposed to teach CSE. These factors are tested with the TSE-Q.

Sampling

In collaboration with the South African Department of Education, two special schools in eThekweni and Cape Town were purposively selected. One school was for learners with hearing impairments and the Deaf, and the other was for learners with intellectual disabilities. Despite inclusive education policies, South Africa predominately provides education to learners with disabilities in ‘special schools.’ In these schools, educators often work across subjects; hence all teachers are important for implementing sexuality education. In addition, these schools have therapists, learning assistants, and NGO staff who support the learning process and student development. Many of them may be tasked to implement elements of CSE in formal Life Orientation sessions (which include CSE), therapy sessions, or extramural activities. Many schools also have boarding establishments with house mothers who must address CSE issues. Therefore, all educational staff members, including teachers and support staff, were invited to participate in the BtS study and workshop training. Recruited participants were invited to fill in the TSE-Q before and after workshop exposure. During the pre-survey, participants were also asked to fill in the validation questionnaire of the TSE-Q. Overall, 50 staff members volunteered to participate from both schools, as presented in figure 2.

Research Tools

To assess educator CSE knowledge, attitudes, perceived norms, skills, confidence, and how they relate to implementing CSE (reported teaching practice), we adapted the BtS Teacher Sexuality Education Questionnaire (TSE-Q) [35]. The original TSE-Q questionnaire was developed, piloted, and validated in KZN and included self-developed and culturally adapted scales from Howard-Barr, Rienzo, Morgan Pigg and James [38] and Mathews, Boon, Flisher and Schaalma [39] (see Table 3) [40,41,42,43]. For this study, we adapted the questionnaire further. We included self-developed questions prompting the educators’ knowledge about CSE in South Africa (Table 1). Example questions can be found in Online Resource 1.

To test the face and content validity of the TSE questionnaire, we asked educators to validate the TSE-Q with an adapted version of Rowe, Oxman, and O’Brien’s validity questionnaire [44]. This validity questionnaire has been used and adjusted to fit the context of CSE in South Africa in our previous study [13]. The validity questionnaire prompts face validity, content validity, and ease of usage (see Table 2). In addition, it tests whether the questionnaire makes sense on a basic level and can be used by the target population. Hence, it tests whether an instrument is meaningful to respondents [45]. Additionally, once the questionnaires were submitted, we allowed participants to provide additional verbal feedback.

Procedure and Ethics

The baseline survey with the TSE-Q and validity questionnaire were conducted before the exposure to the BtS training. The survey and questionnaire were administered using paper versions of the questionnaire. Questionnaires and data were anonymized using participant identifiers and entered into Excel. In addition, the experience of filling in the questionnaire was verbally validated with the participating educators.

Participation in this study was voluntary. All participants were informed about the study verbally and in writing before participating. Those who chose to participate signed an informed consent form. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the South African Medical Research Council (EC047-11-2020).

Analysis

The analysis for this paper consists of descriptive statistics for our sample’s demographic variables and the validity question, as well as reliability testing. The reliability of each scale in the TSE-Q was estimated using McDonald’s omega and Cronbach’s alpha from the baseline questionnaire. Where the alpha was lower than 0.8, items were sequentially eliminated if removing them increased the overall alpha. All analyses were performed in R 4.2.1. McDonald’s omega and Cronbach’s alpha were calculated individually for each scale using the psych package (version 2.2.5). As discussed in Watkins [49], alpha is generally inappropriate as a measure of reliability, but as it is so widely used, we have included it alongside the suggested omega [49].

Descriptive statistics are also presented for the validation questionnaire, noting frequencies for each category of responses in the content validity, face validity, and ease of usage domains. Poorly performing categories were flagged and raised in our validation discussions with educators from each school to understand what adaptations were needed for the TSE-Q.

Results

Table 3 covers the demographic variables collected in the study. It shows that most participants were women (92%) and between the ages of 31 and 60 (86%), with only a few older and younger participants. Most participants were Christian (70%), 44% of the participants were support staff at the school, and most educators had at least four years of teaching experience (46%). Furthermore, 61% of the educators were teaching LO or sexuality education, but only 47% of these educators had formal training in Life Orientation.

Cronbach’s alphas and McDonald’s omegas for the various sets of questions being tested are shown in Table 4. Most of the sets of questions showed good performance with alphas and omegas over 0.8, deeming them suitable to be considered as validated scales. Several of these scales had excellent performance with alphas over 0.9, namely, the ‘Human development,’ ‘Personal skills,’ and ‘Sexual behavior’ scales of the CSE teaching beliefs section; the ‘Human development,’ ‘Relationships,’ ‘Personal skills,’ and ‘Sexual health’ scales of the CSE teaching practices section; and the self-efficacy scale. The ‘CSE policy knowledge,’ ‘CSE beliefs,’ ‘Disability and sexuality beliefs,’ and ‘disability and HIV-risk belief’ set of questions showed poorer performance and were considered for adjustment to develop validated scales. Removing poorly performing items improved the performance of the ‘CSE impact beliefs,’ ‘Disability and sexuality beliefs,’ and ‘disability and HIV-risk belief’ set of questions and enabled the team to construct a validated scale.

The face validity, content validity, and ease of usage of the TSE-Q based on the participants’ feedback in our validity questionnaire is shown in Table 5. The face validity of the questionnaire was acceptable, with 60–80% of participants agreeing that they could understand and use the TSE-Q and its answer options. The content validity questions also revealed acceptable levels. Most participants agreed that the TSE-Q captured the intended content and described their view of teaching CSE. They also felt that they could find their answer in the list of possible answers, that the instrument was not missing any important items, and that the questions were not out of order. However, a slight majority of participants felt that some items were repetitive or redundant. The authors discovered that some questions were duplicated in the physical copy of the TSE-Q that was provided to participants (printing error).

In terms of the ease of using the questionnaire, most participants found that answering the questionnaire helped them in some way, that they were comfortable answering the questions, and that the questionnaire was useful in describing their experiences of teaching CSE. A slight majority of participants felt that the questionnaire did not require too much effort to complete. An even split of participants found that the questionnaire made them think about things they preferred not to think about. Finally, most participants felt that the questionnaire was too long to complete, indicating that this questionnaire needs dedicated time and effort to be filled in appropriately.

Discussion

The TSE-Q was designed to assess the needs and experiences of educators teaching CSE to learners with disabilities in South Africa. The initial study reported on the questionnaire’s development, cultural adaption, and piloting [36]. This paper extends this work by refining existing TSE-Q questions and adding new items. The TSE-Q development was guided by the adapted TPB, which aided in identifying relevant scales from other surveys and in develo** new items.

As a whole, the TSE-Q aims to measure the theoretically relevant predictors of CSE teaching behavior (CSE Teaching Practices scales) based on the TPB. It does this through scales that were identified or developed to measure attitudes (Disability and SRHR beliefs/attitudes, CSE teaching beliefs scales), norms (Perceived Subjective Norms scale), self-efficacy (Self-Efficacy and Confidence scale), skills (Teacher knowledge scale), and environmental constraints (Material and professional preparation scale). The TSE-Q does not measure behavioral intention directly since it is a combination of attitudes, norms, and self-efficacy.

Most reliability tests show good reliability based on Cronbach’s Alpha and McDonald’s Omegat. Based on Cronbach’s Alpha and using a cut-off of 0.7 for scale acceptability (ref), most sets of questions in the questionnaire, except the one on CSE knowledge, can be considered acceptably reliable and be considered a validated scale. McDonald’s omega further confirms this finding. Like Cronbach’s alpha, McDonald’s omega is a measure of reliability and can be interpreted in the same way as alpha. However, it is considered to estimate reliability more accurately and requires fewer statistical assumptions to be met. The reliability estimates for McDonald’s omega are all above 0.7, showing that all sets of questions perform acceptably as validated scales. Hence, the TSE-Q scales are acceptably reliable, with the CSE knowledge set of questions being the only weak ‘scale.’

The content validity, face validity, and ease of usage components of the validity questionnaire help to assess the measure’s validity and identify areas for improvement. For instance, by flagging the repeated questions in the physical copy of the TSE-Q. The validity questionnaire showed that the questions and instructions of the TSE-Q were clear to participants. However, filling in the questionnaire takes time and can be exhausting in terms of length and topic. Hence, this questionnaire should not be filled in directly before and after a workshop but on a different day when participants have enough time and energy to complete the questionnaire.

The TSE-Q is now a finalized questionnaire that can be used to assess educators’ knowledge, beliefs, practices, self-efficacy, and preparedness to teach CSE to young people with disabilities or evaluate programs that try to improve teachers’ ability to provide CSE in accessible formats. As such, a potential next step is to use the TSE-Q in larger studies assessing educators or evaluating programs focusing on CSE, including the Breaking the Silence intervention. In addition, the TSE-Q could be adapted and tested for other countries.

Limitations and Future Directions

This paper is based on a relatively small sample of 50 participants. While this is regarded as acceptable [50], future work should sample a larger number of participants (n > 200) such as recommended by Frost et al. [51]. It is also important to note that the study only covered two schools, so future testing should also include a wider range of disabilities and greater number of schools to improve generalizability. Finally, while all teachers in this sample were fluent in English, it may be necessary to translate the tools so that teachers can complete the questionnaire in their languages of preference.

Conclusion

The TSE-Q is a robust survey tool with validated scales that can be utilized to assess educators’ beliefs, skills, self-confidence, and environmental conditions that enable them to provide CSE to learners with disabilities. It can be used as a cross-sectional survey tool or to evaluate CSE training workshop outcomes. It is validated and adapted for the South African context and might be suitable for other African contexts. The methods followed in this and the previous paper provide a good starting point for adapting the questionnaire for other contexts.

References

Handicap International and Save the Children: Out from the Shadows. Sexual Violence Against Children with Disabilities. Save the Children Fund, London (2011)

Shisana, O., Rehle, T., Simbayi, L., Zuma, K., Jooste, S., Zungu, N., et al.: South African National HIV Prevalence, Incidence and Behaviour Survey, 2012. HSRC, Cape Town (2014)

De Beaudrap, P., Mac-Seing, M., Pasquier, E.: Disability and HIV: A systematic review and a meta-analysis of the risk of HIV infection among adults with disabilities in Sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS Care. 26(12), 1467–1476 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2014.936820

De Beaudrap, P., Beninguisse, G., Pasquier, E., Tchoumkeu, A., Touko, A., Essomba, F., et al.: Prevalence of HIV infection among people with disabilities: A population-based observational study in Yaoundé, Cameroon (HandiVIH). The Lancet HIV. 4(4), e161–e168 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/s2352-3018(16)30209-0

DeBeaudrap, P., Beninguisse, G., Moute, C., Temgoua, C.D., Kayiro, P.C., Nizigiyimana, V., et al.: The multidimensional vulnerability of people with disability to HIV infection: Results from the handiSSR study in Bujumbura, Burundi. EClinicalMedicine. 25, 100477 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100477

Hughes, K., Bellis, M.A., Jones, L., Wood, S., Bates, G., Eckley, L., et al.: Prevalence and risk of violence against adults with disabilities: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Lancet. 379(9826), 1621–1629 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61851-5

Jones, L., Bellis, M.A., Wood, S., Hughes, K., McCoy, E., Eckley, L., et al.: Prevalence and risk of violence against children with disabilities: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Lancet. 380(9845), 899–907 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60692-8

Van der Dunkle, K., Stern, E., Chirwa, E.: Disability and Violence Against Women and Girls Global Programme. What Works, London (2018)

n der Heijden, I., Dunkle, K.: What Works Evidence Review – Preventing violence against women and girls with disabilities in lower – and middle-income countries (LMICs). What Works: Cape Town (2017)

UNFPA: The Right to Access. Regional Strategic Guidance to Increase Access to Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights (SRHR) for Young Persons with Disabilities in east and Southern Africa. UNFPA, Pretoria (2018)

South African National AIDS Council: Let our Actions Count. South Africa’s National Strategic Plan on HIV, TB and STIs 2017–2022. SANAC, Pretoria (2017)

South African Department of Women Youth and Persons with Disabilities: National Strategic Plan on Gender-based Violence and Femicide Strategic Plan 2020–2030. Pretoria (2020)

UNESCO: Needs Assessment on the Current State of CSE for Young People with Disabilities in the east and Southern African Region. Harare, UNESCO (2021)

UNESCO: Young People Today, time to act now: why Adolescents and Young People need Comprehensive Sexuality Education and Sexual and Reproductive Health Services in Eastern and Southern Africa. UNESCO, Paris (2013)

Kirby, D.B., Laris, B.A., Rolleri, L.A.: Sex and HIV education programs: Their impact on sexual behaviors of young people throughout the world. J. Adolesc. Health. 40(3), 206–217 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.11.143

Chappell, P.: How Zulu-speaking youth with physical and visual disabilities understand love and relationships in constructing their sexual identities. Cult. Health Sex. 16(9), 1156–1168 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2014.933878

Chappell, P.: Dangerous girls and cheating boys: Zulu-speaking disabled young peoples’ constructs of heterosexual relationships in Kwazulu-Natal, South Africa. Cult. Health Sex. 19(5), 587–600 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2016.1256433

Chappell, P.: Secret languages of sex: Disabled youth’s experiences of sexual and HIV communication with their parents/caregivers in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Sex Educ. 16(4), 405–417 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2015.1092432

Louw, Q., Brown, S.-M., Twa, N.: Early Detection of Spinal Tuberculosis. An Evidence Synthesis for the South African Context. Stellenbosch University, Cape Town (2018)

Kamaludin, N.N., Muhamad, R., Mat Yudin, Z., Zakaria, R.: Barriers and concerns in providing Sex Education among children with intellectual disabilities: Experiences from malay mothers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 19(3) (2022). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031070

Hanass-Hancock, J., Bakaroudis, M., Johns, R.: Breaking the Silence. Life skills-based Comprehensive Sexuality Education for Young People with Disabilties. Facilitator Guide. SAMRC, UNFPA, PSH, Durban (2022)

Rohleder, P.: Educators’ ambivalence and managing anxiety in providing sex education for people with learning disabilities. Psychodynamic Pract. 16(2), 165–182 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1080/14753631003688100

Rohleder, P., Braathen, S.H., Swartz, L., Eide, A.H.: HIV/AIDS and disability in Southern Africa: A review of relevant literature. Disabil. Rehabilitation. 31(1), 51–59 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1080/09638280802280585

Rohleder, P., Swartz, L.: Providing sex education to persons with learning disabilities in the era of HIV/AIDS: Tensions between discourses of human rights and restriction. J. Health Psychol. 14(4), 601–610 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105309103579

Aderemi, T.J.: Teachers’ perspectives on sexuality and sexuality education of Learners with Intellectual Disabilities in Nigeria. Sex. Disabil. 32(3), 247–258 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-013-9307-7

UNFPA: Young Persons with Disabilities: Global Study on Ending gender-based Violence, and Realising Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights. UNFPA, New York (2018)

UNFPA: Women and Young Persons with Disabilities. Guidelines for Providing rights-based and gender-responsive Services to Address gender-based Violence and Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights. UNFPA, New York (2018)

de Reus, L., Hanass-Hancock, J., Henken, S., van Brakel, W.: Challenges in providing HIV and sexuality education to learners with disabilities in South Africa: The voice of educators. Sex Educ. 15(4), 333–347 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2015.1023283

Chirawu, P., Hanass-Hancock, J., Aderemi, T.J., de Reus, L., Henken, A.S.: Protect or enable? Teachers’ Beliefs and Practices regarding provision of Sexuality Education to Learners with disability in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Sex. Disabil. 32(3), 259–277 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-014-9355-7

Hanass-Hancock, J., Chappell, P., Johns, R., Nene, S.: Breaking the silence through delivering Comprehensive Sexuality Education to Learners with Disabilities in South Africa: Educators experiences. Sex. Disabil. 36(2), 105–121 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-018-9525-0

Hanass-Hancock, J., Nene, S., Johns, R., Chappell, P.: The impact of contextual factors on Comprehensive Sexuality Education for Learners with Intellectual Disabilities in South Africa. Sex. Disabil. 36(2), 123–140 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-018-9526-z

SAMRC: Breaking the Silence. SAMRC: Durban. (2020). https://www.samrc.ac.za/intramural-research-units/breaking-silence Accessed 9 September 2022

Johns, R., Bakaroudis, M., Hanass-Hancock, J.: Breaking the Silence, Life Skills Based Comprehensive Sexuality Education for Young People with Disabilities. Lesson Plans. UNFPA, SAMRC, PSH, Pretoria (2021)

Johns, R., Chappell, P., Bakaroudis, M., Hanass-Hancock, J.: Breaking the Silence, Life Skills Based Comprehensive Sexuality Education for Young People with Disabilities. Comprehensive Guide. UNFPA, SAMRC, PSH, Pretoria (2021)

Hanass-Hancock, J., Mthethwa, N., Bean, T., Carpenter, B., Bakaroudis, M., Johns, R., et al.: Leaving no One Behind - Feasibility Case Study: Applying the “Breaking the Silence” Approach in Comprehensive Sexuality Education for Adolescents and Young People with Disabilities During the COVID-19 Epidemic. SAMRC, UNFPA, PSH, AmplifyChange Durban (2021)

Hanass-Hancock, J., Henken, S., Pretorius, L., de Reus, L., van Brakel, W.: The cross-cultural validation to measure the needs and Practices of educators who teach Sexuality Education to Learners with a disability in South Africa. Sex. Disabil. 32(3), 279–298 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-014-9369-1

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services National Institutes of Health: Theory at a Glance. A Guide For Health Promotion Practice (Second Edition). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services National Institutes of Health, USA: (2005)

Howard-Barr, E.M., Rienzo, B.A., Pigg, M., James, R.: Teacher beliefs, professional preparation, and practices regarding exceptional students and sexuality education. J. Sch. Health. 75(3), 99–104 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1561.2005.00004.x

Mathews, C., Boon, H., Flisher, A.J., Schaalma, H.P.: Factors associated with teachers’ implementation of HIV/AIDS education in secondary schools in Cape Town, South Africa. AIDS Care. 18(4), 388–397 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1080/09540120500498203

Ward, E., Hanass-Hancock, J., Amon, J.J.: Left behind: Persons with disabilities in HIV prevalence research and national strategic plans in east and Southern Africa. Disabil. Rehabil. 44(1), 114–123 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2020.1762124

Hanass-Hancock, J., Mthethwa, N., Bean, T., Mnguni, M., Bakaroudis, M.: Sexual and reproductive health and rights and disability policy analysis. The South African case report updated March 2021. SAMRC, UNFPA, PSH: Durban (2021)

World, Y.W.C.A.: Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights for Adolescents in sub-Saharan Africa. Youth fact Sheet. W. YWCA, Editor (2017)

The Global Fund: Technical Brief: HIV programming for adolescent girls and young women in high-HIV burden settings. The Global Fund: (2020)

World Health Organisation and UNFPA: Promoting Sexual and Reproductuve Health for Persons with Disabilties. Guidance Note. WHO/UNFPA, Geneva (2009)

COVID-19 Disability Rights Monitor and Siobhan, Brennan, C.: Disability rights during the pandemic. A global report on findings of the COVID-19 Disability Rights Monitor. Validity, ENIL, IDA, DRI, CfHR, IDDC, DRF, DRAF: Online (2020)

Ward, T., Bernier, R., Mukerji, C., Perszyk, D., McPartland, J.C., Johnson, E., et al.: Face Validity. In: Volkmar, F.R. (ed.) Encyclopedia of Autism Spectrum Disorders, pp. 1226–1227. Springer New York, New York, NY (2013)

Offit, P.A., Snow, A., Fernandez, T., Cardona, L., Grigorenko, E.L., Doyle, C.A., et al.: Validity. In: Volkmar, F.R. (ed.) Encyclopedia of Autism Spectrum Disorders, pp. 3212–3213. Springer New York, New York, NY (2013)

Karahanna, E., Straub, D.W.: The psychological origins of perceived usefulness and ease-of-use. Inf. Manag. 35(4), 237–250 (1999). https://doi.org/10.1016/s0378-7206(98)00096-2

Watkins, M.W.: The reliability of multidimensional neuropsychological measures: from alpha to omega. Clin Neuropsychol. 31(6–7), pp. 1113–1126 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1080/13854046.2017.1317364

Bujang, M.A., Omar, E.D., Baharum, N.A.: A review on sample size determination for Cronbach’s alpha test: A simple guide for researchers. Malays J. Med. Sci. 25(6), 85–99 (2018). https://doi.org/10.21315/mjms2018.25.6.9

Frost, M.H., Reeve, B.B., Liepa, A.M., Stauffer, J.W., Hays, R.D., Patient-Reported Outcomes Consensus Meeting Group: What is sufficient evidence for the reliability and validity of patient-reported outcome measures? Value Health. 10(2), S94–S105 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00272.x

Funding

Open access funding provided by South African Medical Research Council.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Jill Hanass-Hancock and Maria Bakaroudis contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by Jill Hanass-Hancock and Bradley Carpenter. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Bradley Carpenter and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethics Approval

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the South African Medical Research Council (EC047-11-2020).

Consent to Participate

Written informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent to Publish

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Carpenter, B., Bakaroudis, M. & Hanass-Hancock, J. Validating the Teacher Sexuality Education Questionnaire Scales to Assess Educators’ Preparedness to Deliver CSE to Young People with Disabilities. Sex Disabil 41, 677–690 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-023-09798-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-023-09798-8