Abstract

The Directorate General for Competition at the European Commission enforces competition law in the areas of antitrust, merger control, and State aid. After providing a general presentation of the role of the Chief Competition Economist’s team (CET), this article surveys some of the main developments at the Directorate General for Competition over 2022/2023. In particular, the article reviews the Commission antitrust investigation of Amazon marketplace and the Amazon “Buy Box”, the expansion of manufacturing support with two recent frameworks for manufacturing aid, and the MOL/OMV merger.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Executive Vice-President Vestager, who held the competition portfolio since 2014, took a temporary leave of absence in September 2023. Subsequently, Commissioner Reynders has been appointed as the European Commission’s Commissioner for Competition, while he also retains his position as Commissioner for Justice.

ByteDance is the owner of the social network TikTok.

Art 101 TFEU prohibits anti-competitive agreements between undertakings. Art 102 TFEU prohibits abuses of a dominant position by one or more undertakings.

Beyond e-commerce, Amazon is also active in a number of adjacent activities, such as video and music streaming, publishing, cloud computing and artificial intelligence.

Since Amazon Retail and FBA third-party sellers use the Amazon fulfillment network, they are referred to as “Amazon Fulfillment Network (AFN) sellers”.

An Amazon Standard Identification Number (ASIN) is a unique identifier for each product in Amazon’s internal system. Each product model, size, or colour of a particular product corresponds to a different ASIN.

For a small proportion of customer visits to products’ detailed pages, a Featured Offer may not be displayed.

Over time Amazon introduced changes to the display of alternative offers, but consumer engagement with these offers remained very low.

Paras 41–42.

Para 40.

In the vast majority of Prime user visits (around 80–90%), the Featured Offer is Prime labelled, which signals to Prime members that the advantages of the Prime programme—free and quick delivery—apply (para 215). Thus, Prime labelled offers are preferred by Prime members in the majority of cases. Indeed, most of the total expenditure of Prime members involves Prime offers (para 139).

MFN stands for “Merchant Fulfilled Network”.

Italy is excluded from the commitments that relate to the Buy Box and to Prime in view of the decision of 30 November 2021 of the Italian competition authority that imposed remedies on Amazon with regard to the Italian market.

The daily periodic penalty payment would amount to 5% of Amazon’s average daily turnover in the business year preceding its failure to comply (para 289).

Further principles include the incentive effect, the appropriateness as well as transparency. See https://ec.europa.eu/competition/state_aid/reform/economic_assessment_en.pdf.

For example, asymmetric information is relevant for the financing of projects of smaller firms with limited access to finance (the Risk Finance Guidelines), and coordination failure issues affect complex research and development projects (the R&D&I Guidelines).

This is often the case when the aid amounts are relatively low. Different aid intensities are set for different type of projects.

One should also note that subsidy races also result in a transfer from tax payers to the beneficiary as the subsidy exceeds what the beneficiary strictly requires to perform the economic activity. This has equity implications.

See the Commission’s Framework for State aid for research and development and innovation.

Under regional aid guidelines, manufacturing aid is possible to the extent that an equity objective is pursued and under restrictive conditions. Under IPCEI Communication, the aid is provided to cover eligible costs (up to the funding gap) in the R&D phase as well as the first industrial deployment; but aid cannot be provided to cover costs that are related to the mass production phase.

See https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=uriserv%3AOJ.L_.2023.229.01.0001.01.ENG. The Chips Act for Europe Communication (“Chips Act Communication”) of 8 February 2022 which pre-dated the Chips Act and accompanied the Chips Act proposal outlines some basic State aid assessment principles, see eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri = CELEX:52022DC0045.

See https://commission.europa.eu/system/files/2021-05/communication-industrial-strategy-update-2020_en.pdf. The need for an analysis of the strategic dependencies—both technological and industrial—of the EU is underlined, and such a bottom-up analysis is performed.

The impact of such programs, and in particular of the IRA has been heavily discussed. For example a report from the French and German Council of Economic Experts suggest that the impacts may be smaller than anticipated, see https://www.lemonde.fr/en/opinion/article/2023/09/22/the-inflation-reduction-act-does-not-present-major-economic-security-risks-for-the-eu_6138513_23.html.

See, e.g., Tagliapietra et al. (2023)

For example, as is further explained in the European Chips Act Communication, following the Covid-19 shortages, European carmakers have called for an increase in EU chip production capacity and reduced reliance on foreign imports.

Semiconductors is a core industry that is central to this plan.

The Chips and Science Act envisages around USD 280 billion to enhance research—and also the manufacturing of semiconductors in the US.

The first IPCEI in the field of Microelectronics was approved in 2018 with an objective to enable research and develop innovative technologies and components (e.g. chips, integrated circuits, and sensors). The second IPCEI on Microelectronics was approved in 2023: The objective is to enable the digital and green transformation in Europe. https://competition-policy.ec.europa.eu/state-aid/legislation/modernisation/ipcei_en.

Aid can be granted for research and first industrial deployment activities—as opposed to mass manufacturing.

https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_22_5970. European Commission’s Decision is accessible via https://competition-cases.ec.europa.eu/cases/SA.103083.

Some examples: Germany’s new chip factories: a bet on the future or waste of money? | Financial Times (ft.com), Intel plans €4.6B microchips factory in Poland—POLITICO, Germany earmarks 20 billion euros in subsidies for chip industry | Reuters, Infineon to begin work on 5 bln euro chip plant in Germany | Reuters.

See Chips Act Communication, page 16.

For example in the STM decision (p. 28), it is explained that the company has committed to prioritise orders of semiconductors, intermediate products, and raw materials that are required to produce semiconductors or intermediate products that are affected by the semiconductor crisis or that are of strategic importance to remedy the semiconductor crisis or economic effects thereof and to set the prices of crisis-relevant products at fair and reasonable levels; and if the company is unable to perform this due to insufficient capability or the request imposes an unreasonable economic burden for the company, in such case the company will ask the Commission to review the order.

See Chips Act Communication, fn. 15,

See Chips Act Communication, fn. 57.

See the STM decision, p. 37.

Chips Act Communication, fn. 57.

This holds as long as the project NPV in the counterfactual is positive and absent the aid the investment project would be undertaken elsewhere.

For example, a project that would not generate positive earnings-before-interest-and-taxes (EBIT) results for at least some years will be unlikely to be viable over the longer term.

The NZIA sets the new industrial plan for the net zero age. This includes measures to improve the competitiveness of the EU net-zero industry, with regulatory simplifications, the Critical Raw Materials Act to improve the security of supply for raw material, as well as a reform of the electricity market design.

The TCTF builds on the Temporary Crisis Framework, which was established in the aftermath of the Russian aggression against Ukraine.

https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52022XC0324(10). Note that this initial framework was based on article 107.3.b of the TFEU, which enables the Commission to consider compatible support to “remedy a serious disturbance in a Member State’s economy”. This framework was also expanded in October 2022 to include solvency support—which was used in landmark cases of Uniper and SEFE—but also aid for: accelerating the rollout of renewable energy, storage, and renewable heat that is relevant for REPowerEU (Section 2.5); the decarbonisation of industrial production processes (Section 2.6); and the additional reduction of electricity consumption (Section 2.7). See https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52022XC1109(01). Since they focus on investment projects, the last three sections fall under article 107.3.c of the TFEU.

A scheme provides the legal basis for aid to companies under specific conditions (such as eligibility, and proportionality). In a scheme, typically several companies are eligible for aid—as opposed to individual aid, which is targeted at one company.

Point 85g.

Point 85h.

Point 85d.

Point 85f.

Point 85L.

Also footnote 150 notes that “Undertakings from all Member States which are active in the relevant value chain must be given a genuine opportunity to participate in an emerging project. Notifying Member States must demonstrate that such undertakings were informed of the possible emergence of a project.”

Point 86e.

Point 86.

Under the regional aid guidelines there are exceptions on operating aid schemes, but these aim to “compensate[s] for additional costs incurred in pursuing an economic activity in outermost regions, or if it prevent[s] or reduce[s] depopulation in sparsely and very sparsely populated areas” (point 15).

TCTF, footnote 154.

“A” regions are the regions that are most in need of support.

TCTF, footnote 156.

A similar provision exists under RAG point 117, whereby in a location decision, if without the aid the investment would have taken place in an area with more need for assistance, then providing aid in a “less in need” area would lead to a counter-cohesion effect that is unlikely to be compensated for by any positive effect. This ensures that richer areas do not steal projects from poorer areas– if the latter would instead be selected by the companies.

This is also explained in the RAG, point 115.

ECJ Judgement of 13 July 2023 in Case-376/20 P European Commission vs. CK Telecoms.

GC Judgement of 13 July 2022 in Case T-227/21 Illumina vs. European Commission.

Commission Guidance on the application of the referral mechanism set out in Article 22 of the Merger Regulation to certain categories of cases, 26 March 2021, available at: https://ec.europa.eu/competition/consultations/2021_merger_control/guidance_article_22_referrals.pdf.

Case M.10188 Illumina/Grail (Commission decision of 6 September 2022).

See, e.g., Cunningham et al. (2021).

See, e.g., Wollmann (2019).

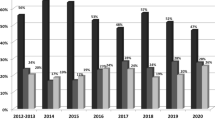

Mergers must be notified to the European Commission if the annual turnover of the combined business exceeds certain thresholds in terms of global and European sales. Notification triggers a 25-working-day phase I investigation. In the majority of cases, this follows a simplified procedure. If the transaction does not raise serious doubts with respect to its compatibility with the common market at the end of phase I, the Commission issues an unconditional clearance decision. If concerns exist but are addressed in a clear‑cut manner by remedies that have been proposed by the parties, the transaction can be cleared conditionally in phase I. Otherwise, the Commission will start a 90‑working‑day phase II investigation. At the end of phase II, the transaction is either cleared (conditionally or unconditionally) or prohibited; the latter occurs if the Commission finds that the transaction would lead to a significant impediment of effective competition even after taking into account any commitments that have been proposed by the parties. Details on the European Union merger regulation are available at https://ec.europa.eu/competition/mergers/procedures_en.html (accessed 31 July 2023). Detailed statistics on the number of merger notifications and decisions are available at https://ec.europa.eu/competition/mergers/statistics.pdf (accessed 31 July 2023).

Case M.10658 Norsk Hydro/Alumetal (Commission decision of 4 May 2023); Case M.10807 Viasat/Inmarsat T(Commission decision of 25 May 2023).

Case M.10262 Meta (formerly Facebook)/Kustomer (Commission decision of 27 January 2022); Case M.10078 Cargotec/Konecranes (Commission decision of 24 February 2022); Case M.10663 Orange/VOO/Brutélé (Commission decision of 20 March 2023); Case M.10663 Microsoft/Activision Blizzard (Commission decision of 15 May 2023); Case M.10438 MOL/OMV Slovenija (Commission decision of 17 May 2023); Case M.10433 Vivendi/ Lagardère (Commission decision of 9 June 2023); Case M.10806 Broadcom/VMware (Commission decision of 12 July 2023).

Case M.9343 HHI/DSME (Commission decision of 13 January 2022); Case M.10188 Illumina/Grail (Commission decision of 6 September 2022).

Case M.9987 NVIDIA/ARM (withdrawn 8 February 2022); Case M.10319 Greiner/Recticel (withdrawn 28 February 2022); Case M.9938 Kingspan/Trimo (withdrawn 21 April 2022); Case M.10325 Kronospan/Pfleiderer Polska (withdrawn 29 November 2022).

4.7%=25/328. 25 interventions: 12 Phase I commitments, 7 Phase II commitments, 2 Phase II prohibitions, 4 Phase II abandonments. The 10 Phase I abandonments are not counted in the numerator or denominator, as those cases can, in principle, immediately be re-notified.

Case M.10438 MOL/OMV Slovenija (Commission decision of 17 May 2023).

Petrol is the former state monopoly provider, and currently is the largest seller in the market.

Cases M.9014 PKN Orlen/Grupa Lotos (Commission decision of 14 July 2020) and M.7603 Statoil Fuel and Retail/Dansk Fuels (Commission decision of 23 March 2016).

See, e.g., Farrell and Shapiro (2010).

Each customer population grid provides the population of the respective grid.

As compared to a supply-centric approach, a customer-centric approach puts a stronger emphasis on customers’ locations. Relying on customer population grids ignores the possibility that customers are not static and may decide for example to drive to the fuel station, on their way from work.

Facing these limitations, the parties developed an econometric framework to derive diversion ratios from a logit demand model, where the utility of the customer for a given fuel station was a function of the distance between the fuel station and the customer grid. The practical implementation consisted in calibrating ‘customer choices’ so as to obtain average catchment areas around fuel stations of 15 minutes, rather than to calibrate them to observed outcomes.

In Slovenia, margins were regulated based on a margins cap. The full liberalisation of the market was gradually introduced between 2016 and October 2020. In March 2022, following Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine, the Slovenian government reinstated price regulation. Facing a long period of price regulation, the margins observed in Slovenia were relatively low and did not necessarily represent equilibrium margins. However, it is unclear why the competitive conditions in the EU overall could be representative for the competitive conditions in Slovenia.

For an overview of the assessment framework that is described in the Horizontal Merger Guidelines, and a review of the recent decisional practice of the European Commission towards coordinated effects in mergers, see Piechucka (2023).

Unlike other firms, OMV Slovenija applied local pricing to some extent: e.g., for some stations in the tourist season or for stations that are located near the border to Italy. These cases, however, are the exception rather than the rule in Slovenia.

Pursuant to Slovenian law, price changes that fuel retailers intend to implement for diesel main grade and premium, gasoline main grade and premium, heating oil, and LPG are provided to the Ministry of Economic Development and Technology before their actual implementation. These price changes are made public on goriva.si once they become effective.

See https://www.ina.hr/en/about-ina/core-business/refining-and-marketing/rijeka-refinery-upgrade-project/ (accessed 31 July 2023).

References

Cunningham, C., Ederer, F., & Ma, S. (2021). Killer acquisitions. Journal of Political Economy, 129(3), 649–702.

Farrell, J., & Shapiro, C. (2010). Antitrust evaluation of horizontal mergers: An economic alternative to market definition. B E Journal of Theoretical Economics, 10(1), 1–39.

Piechucka, J. (2023). Coordinated effects of mergers: The EC perspective. Antitrust Chronicle Summer-July, 2(2), 35–41.

Tagliapietra, S., Veugelers, R., & Zettelmeyer, J. (2023). ‘Rebooting the European Union’s Net Zero Industry Act’ Policy Brief 15/2023, Bruegel.

Wollmann, T. (2019). Stealth consolidation: Evidence from an amendment to the Hart-Scott-Rodino Act. American Economic Review: Insights, 1(1), 77–94.

Acknowledgements

The views that are expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of DG Competition or the European Commission. We would like to thank Thomas Buettner, Szabolcs Lorincz, Fernando Sanchez Carrillo, and Koen Van de Casteele for helpful comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed equally to this manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Koltay, G., Kotzeva, R., Lelièvre, G. et al. Recent Developments at DG Competition: 2022/2023. Rev Ind Organ 63, 545–577 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11151-023-09936-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11151-023-09936-8