Abstract

The conventional belief regarding the frequency of property assessment has been that annual revaluation is optimal. Practices, however, vastly differ from this norm and the length of assessment cycles diverge widely across tax assessing jurisdictions. This study fills a gap in the literature by examining the relation between cycle length and assessment outcomes, using panel data from the early 2000s to 2016 in Virginia and New York as two representative states. We examine the conditional correlation between revaluation lag and assessment uniformity among tax assessing jurisdictions in Virginia. We find that assessment uniformity tends to be lower by three to six percent when revaluation is delayed by an additional year; however, the rate of deterioration does not vary across jurisdictions with different cycle lengths. In New York, we find that switching from irregular to annual assessment is positively associated with assessment uniformity and administrative costs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Gemmell et al. (2019) provides an informative summary of the literature on different property tax systems and how they vary depending on the government choice of land versus capital as the property tax base.

This becomes particularly challenging in states with property tax limitations that either prevent tax-levying localities from raising their nominal tax rates or limit the growth in levy amount or total assessed values.

Two other states, New Jersey and California, reassess upon sale or improvement.

So called ‘Dillon’s rule’ states limit the powers of local governments to those expressly granted to them in their state’s constitutions and statutes while municipalities in home rule states possess all powers except those expressly withheld from them.

Hou et al. (2023) also underlines the heterogeneous impact of the “Actual Value Initiative” on equity outcomes, by showing that changes in assessment uniformity varies by the average level and appreciation rate of property values; neighborhood’s average income, race and gentrification status.

In the United States, some state governments mandate properties to be assessed at 100% of market value (full assessment), while in other states, the statutory assessment rate represents a certain fraction of the market value (fractional assessment). For instance, local tax assessing jurisdictions in Georgia, which falls under the latter category of states, assess properties at 40 percent of fair market value.

This is based on general guidelines presented in Chapter 56 of the New York State Real Property Tax Law 1573 adopted in 2010. (Last Accessed on Nov/21/2023 and available at: https://www.tax.ny.gov/pdf/publications/orpts/state_aid/cyclical_guidelines.pdf).

Counties are also the primary local level of general-purpose government in Virginia, providing services for public education and health services. Unlike in New York, school districts in Virginia are operated at the county level.

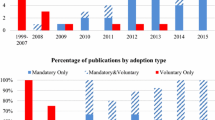

While most counties and cities did not change their assessment cycles after 1984, the Tax Code does not prohibit localities from reassessing more frequently than their pre-determined cycle. Between 2002 and 2016 for example, 36 localities (27 percent of all assessing jurisdictions in VA) elected a shorter cycle than in previous years, and 17 (12 percent) reverted to the mandated cycle. Later we address the concern of whether localities' decision to maintain the pre-determined cycle or pick a different one can be potentially endogenous to assessment outcomes. We do so by comparing the results from the full sample of all jurisdictions and a subsample of jurisdictions that never changed their cycle during the sample period.

The coefficient of dispersion is expressed as: \(COD_i\;=\;\frac{100}{R_j}\;\left(\frac{\sum_1^j\;\left|R_j-R_{median}\right|}N\right)\) where \(\left|R_j-R_{median}\right|\) is the absolute deviation from the median per parcel, the denominator \(N\) is the number of parcels sampled by each property class in the sales data. \(R_j\) is the assessment ratio for each parcel in the sales data, and \(R_{median}\) is the median assessment ratio.

In New York, the assessment function has been terminated at the village level since 1984 in most villages. Approximately 45 villages out of 553 remain assessing units but utilize town or county assessment rolls (Office of the New York State Comptroller, 2010).

New York is among the seven states that do not mandate regular assessment. Among them, New Jersey and California both require reappraisal upon sale or improvement. Massachusetts simply orders its localities with faulty assessment rolls to conduct reassessments; in cases of non-compliance, the state may hire a contractor for the job and charge the locality for the project (Office of the New York State Comptroller, 2010).

Though property tax administration is decentralized in New York, the State’s Department of Taxation and Finance is charged by state law to regularly monitor the equity of assessments. As required by Sect. 1200 of NYS Real Property Tax Law, the Office of Real Property Tax Services in the Department has, since the 1980s, been conducting annual market value survey of real properties in the state, thereby analyzing assessment uniformity (Office of the New York State Comptroller, 2010).

In a nationwide study, Cohen et al. (2012) show that cheaper properties depreciated faster than more expensive houses during the great recession, which would relatively increase the tax burden of owners of cheaper houses, exacerbating tax regressivity.

In 1983, all 553 villages were separate tax assessing units beside 1,546 towns and cities (NYORPTS, 2001). By 2010, only less than one-third (127 out of 553) of villages still had assessors, for village purposes and the total number of assessing jurisdictions was reduced to 1,029 units.

From 1985 to 2000, most assessing units received reassessment aid and conducted valuations according to their submitted plans, whereas one-fifth (192 assessing units) did not reassess a single time (NYSORPTS, 2001).

1970 is the first year when we can observe whether a tax assessing jurisdiction in NY conducted reassessment or not and 2000 is the first year of our sample period. We also control for the cumulative count of assessments in our regression models.

Our results are very similar when limiting the annual cycle treatment definition to at least six consecutive years of annual assessment. See footnote #20. These results are available upon request.

The New York state Office of Real Property Tax Services (ORPTS) only reports COD for a sample of assessing units that have not conduced revaluation over the past three years prior to the market value survey year.

Some of the IAAO standards for acceptable COD ranges related to this study are as follows. Single-family housing: 5 to 10 in new or homogeneous areas, 5 to 15 in older or heterogeneous areas. Other types of residents like rural, seasonal, recreational, manufactured (2–4 units), 5 to 20. Vacant land: 5 to 25. CODs lower than 5 may be due to sales chasing or non-representative sampling (IAAO, 2010).

The average PRD value for jurisdictions that ever committed to annual and triennial cycles were 1.13 and 1.11 respectively, while that of the control group with no regular cycle was 1.25 during our sample years.

The dependent variable is measured as the log of assessment spending per parcel, which is why we apply an exponent 2.79 to calculate the average cost (16.28). The baseline mean values in Table 6 are those of jurisdictions in the control group that did not conduct annual assessment.

This finding is particularly intriguing given that we find suggestive evidence of positive correlation between state assessment aid and the likelihood of committing to an annual or triennial cycle (results shown in Table 8).

\({Treat}_{it}= {\uppi }_{0}+{\uppi }_{1}{frequency\;since1970}_{i,t-1}+{\uppi }_{2}{assessment\;cost}_{i,t-1}+{\uppi }_{3}{COD}_{i,t-1}+{{\varvec{V}}}_{i,t-1}\chi + {\sigma }_{i}+{\lambda }_{t}+{\varepsilon }_{it}\), where \({Treat}_{it}\) is a dummy indicator of whether a jurisdiction i switched to annual (or triennial) cycle or not in year t.

We detect positive correlations between commitment to triennial cycle and assessment uniformity from the prior year, as shown in columns 3 and 4 in Table A4. The evidence is less consistent with annual cycle decision (columns 1 and 2). When using the pooled sample of all municipalities, we do not find significant correlation between annual cycle and assessment uniformity.

Our findings also hold when we subtract state aid from total administrative cost when constructing the dependent variable instead of including state aid as an explanatory variable. Results are available upon request.

See Callaway and Sant’Anna (2021) for further details on their aggregation of group-time average treatment effect on the treated, that address the variation in treatment timing in a different way from Sun and Abraham (2021)’s approach.

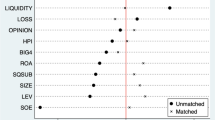

The underlying assumption of this approach is that the parallel trend in outcomes between treated and control holds, conditional on a set of covariates (X), when we suspect imbalance between two groups due to nonrandom selection into treatment.

We narrow our definition of annual cycle as annual assessment for six consecutive years instead of three due to the identifying assumptions of the Callaway and Sant’Anna (2021) estimator. However, the results are similar when redefining treatment as minimum three consecutive years with this alternative estimator, and also when using the smaller treated sample with the baseline estimators (stacked DiD and Sun and Abraham’s event study).

The generally larger and significant estimates from both estimators suggest that the baseline estimates may be biased toward zero. However, we choose to report the more conservative estimates as the baseline results.

However, we do detect differential pretend for two of the main outcomes (deviation in assessment ratio and cost).

The net cost of reassessment may have been higher even after receiving state aid that some jurisdictions in New York State decided to stop investing in annual revaluation. When the town of Cicero conducted reassessment most recently for the first time in over ten years since 2006, the town had to spend approximately $1 million for full revaluation to update their inventory and record of sales. However, the additional revenue the town generated was not enough to offset the cost, even with $67,500 state aid.

Virginia and New York implemented levy limits in 1975 and 2011 respectively. New York State allows jurisdictions to override the state-imposed tax cap if at least 60 percent of local voters approve a levy increase. New York also has a separate assessment limit that only applies to New York City and Nassau County (both of which are not included in the final sample of this study), where the maximum growth rates in assessed values also vary by property class. For instance, for residential property class one comprised of one to three family houses and small condominiums, assessed value cannot grow more than 6 percent each year or more than 20 percent over five years.

If local homeowners are highly aware of the statutory tax rates and oppose constant increases, this may aggravate tax aversion or change preferences for local public services.

Limitations of our three approaches is that there may be other unobservable time varying factors omitted from the model such as changes in political pressure from local taxpayers, productive efficiency of local governments or the influence of changes in neighboring jurisdictions’ assessment practices.

References

Abadie, A. (2005). Semiparametric difference-in-differences estimators. The Review of Economic Studies, 72(1), 1–19.

Amornsiripanitch, Natee. (2020). Why are residential property tax rates regressive? Working paper available at SSRN 3729072.

Anderson, N. B. (2006). Property tax limitations: An interpretative review. National Tax Journal, 59(3), 685–694.

Anderson, J. E., & Shimul, S. N. (2018). State and local property, income, and sales tax elasticity: Estimates from dynamic heterogeneous panels. National Tax Journal, 71(3), 521–546.

Avenancio-León, C. F., & Howard, T. (2022). The assessment gap: Racial inequalities in property taxation. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 137(3), 1383–1434.

Berry, C. R. (2021). Reassessing the property tax. Working paper available at SSRN 3800536.

Bick, Robert & New York Association of Assessors, New York. (2016). [Assessment Staffing Survey]. Unpublished raw data.

Black, D. E. (1977). Property tax incidence: The excise-tax effect and assessment practices. National Tax Journal, 30(4), 429–434.

Bloom, H. S., & Ladd, H. F. (1982). Property tax revaluation and tax levy growth. Journal of Urban Economics, 11(1), 73–84.

Borland, M., & Lile, S. (1980). ‘The property tax rate and assessment uniformity.’ National Tax Journal, 33, 99–102.

Bowman, J. H., & Butcher, W. A. (1986). ‘Institutional remedies and the uniform assessment of property: An updated and extension.’ National Tax Journal, 39, 157–169.

Bowman, J. H., & Mikesell, J. L. (1978). ‘Uniform assessment of property: returns from institutional remedies.’ National Tax Journal, 31, 137–152.

Bowman, J. H. (1990). Improving Administration of the Property tax: A review of prescriptions and their impacts. Public Budgeting and Financial Management, 2(2), 151–176.

Bradbury, K. L., Mayer, C. J., & Case, K. E. (2001). Property tax limits, local fiscal behavior, and property values: Evidence from Massachusetts under proposition 212. Journal of Public Economics, 80(2), 287–311.

Callaway, B., & Sant’Anna, P. H. C. (2021). Difference-in-differences with multiple time periods. Journal of Econometrics, 225(2), 200–230.

Cengiz, D., Dube, A., Lindner, A., & Zipperer, B. (2019). The effect of minimum wages on low-wage jobs. The Quarterly Journal of Economics., 134(3), 1405–1454.

Cohen, Jeffrey P., Cletus C. Coughlin, & David A. Lopez. (2012). The boom and bust of U.S. housing prices from various geographic perspectives. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review, 94(5). Available at https://research.stlouisfed.org/publications/review/2012/09/04/the-boom-and-bust-of-u-shousing-prices-from-various-geographic-perspectives. Accessed 21 Aug 2022.

Coleman, A., & Grimes, A. (2010). Fiscal, distributional and efficiency impacts of land and property taxes. New Zealand Economic Papers, 44(2), 179–199.

Cutler, D. M., Elmendorf, D. W., & Zeckhauser, R. (1999). Restraining the leviathan: Property tax limitation in Massachusetts. Journal of Public Economics, 71(3), 313–334.

Doering, W. (1977). Property tax equalization and conventional measures of assessment performance. In Analyzing Assessment Equity: Techniques for Measuring and Improving the Quality of Property Tax Administration, International Association of Assessing Officers 1977 Symposium Proceedings (pp. 205–216).

Doerner, W., & Ihlanfeldt, K. (2014). An empirical analysis of the property tax appeals process. Journal of Property Tax Assessment & Administration., 11(4), 5.

Doerner, W., & Ihlanfeldt, K. (2015). The role of representative agents in the property tax appeals process. National Tax Journal, 68(1), 59.

Duncombe, W., & Yinger, J. (2007). Does school district consolidation cut costs?. Education Finance and Policy, 2(4), 341–375.

Dye, R. F., & McGuire, T. J. (1997). The effect of property tax limitation measures on local government fiscal behavior. Journal of Public Economics, 66(3), 469–487.

Dye, R. F., & England, R. W. (2009). The principles and promises of land value taxation. In R. F. Dye & R. W. England (Eds.), Land value taxation: Theory, evidence and practice (pp. 3–10). Lincoln Institute of Land Policy.

Dye, R. F., McGuire, T. J., & McMillen, D. P. (2005). Are property tax limitations more binding over time? National Tax Journal, 58(2), 215–225.

Eom, T. H. (2008). A comprehensive model of determinants of property tax assessment quality: Evidence in New York state. Public Budgeting & Finance, 28(1), 58–81.

Franzsen, R. (2009). International experience. In R. F. Dye & R. W. England (Eds.), Land value taxation: Theory, evidence and practice (pp. 28–47). Lincoln Institute of Land Policy.

Gemmell, N., Grimes, A., & Skidmore, M. (2019). Do local property taxes affect new building development? Results from a quasi-natural experiment in New Zealand. The Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics., 58, 310–333.

Geraci, V. J. (1977). Measuring the benefits from property tax assessment reform. National Tax Journal, 30(2), 195–205.

Giertz, J. F., & Chicoine, D. L. (1988). Interjurisdictional fiscal competition and economic development. In Proceedings of the Annual Conference on Taxation Held under the Auspices of the National Tax Association-Tax Institute of America (pp. 42–44). National Tax Association-Tax Institute of America.

Giertz, J. F., & Chicoine, D. L. (1990). Measuring the performance of assessors: Adjusting for the difficulty of the assessing task. Public Budgeting and Financial Management, 2(2), 177–202.

Goldsmith-Pinkham, P., Sorkin, I., & Swift, H. (2020). Bartik instruments: What, when, why, and how. American Economic Review, 110(8), 2586–2624.

Goodman-Bacon, A. (2021). Differences-in-differences with variation in treatment timing. Journal of Econometrics., 225(2), 254–277.

Hayashi, A. (2014). The legal salience of taxation. The University of Chicago Law Review, 81(4), 1443–1507.

Higginbottom, J. (2010). State provisions for property reassessment. Tax Foundation.

Hirano, K., Imbens, G. W., & Ridder, G. (2003). Efficient estimation of average treatment effects using the estimated propensity score. Econometrica, 71, 1161–1189.

Hou, Y., Ding, L., Schwegman, D. J., & Barca, A. G. (2023). [forthcoming] Assessment frequency and equity of the property tax: Latest evidence from Philadelphia. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management. https://doi.org/10.1002/pam.22555

Ihlanfeldt, K., & Rodgers, L. P. (2022). Homestead exemptions, heterogeneous assessment, and property tax progressivity. National Tax Journal, 75(1), 7–31.

Imbens, G. W. (2000). The role of the propensity score in estimating dose–response functions. Biometrika, 87, 706–710.

International Association of Assessing Officers. (2010). Standard on Ratio Studies. Kansas City, MO.

Kim, Y., Hou, Y., & Yinger, J. (2023). Returns to scale in property assessment: Evidence from New York state’s small localities coordination program. National Tax Journal., 76(1), 63–94.

Ladd, H. F. (1991). Property tax revaluation and tax levy growth revisited. Journal of Urban Economics, 30(1), 83–99.

McMillen, D., & Singh, R. (2020). Assessment regressivity and property taxation. The Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics., 60, 155–169.

McMillen, D. & Singh, R., (2022). Assessment Persistence. Working Paper. Available at https://www.isid.ac.in/~acegd/acegd2023/papers/RuchiSingh.pdf

Mikesell, J. L. (1980). Property tax reassessment cycles: Significance for uniformity and effective rates. Public Finance Quarterly, 8(1), 23–37.

Mill, J. S. (1865). Principles of political economy with some of their applications to social philosophy. Longmans, Green, & Co.

Nathan, B. C., Perez-Truglia, R., & Zentner, A. (2020). My taxes are too darn high: Tax protests as revealed preferences for redistribution. NBER Working Paper, w27816. https://doi.org/10.3386/w27816

New York Association of Assessors, New York. (2016). [Assessor Survey]. Unpublished raw data surveyed by Yilin Hou's research team at the Maxwell School, Syracuse University.

Oates, Wallace. E., & Robert M. Schwab. (2009). The simple analytics of land value taxation. In R. F. Dye & R. W. England (Eds.), Land value taxation: Theory, evidence, and practice (pp. 51–72). Lincoln Institute of Land Policy.

Office of the New York State Comptroller. (nda). New York State Open Book: Local Government and School Accountability Financial Data. Albany, NY.

Office of the New York State Comptroller. (2010). Comprehensive Annual Financial Report. Albany, NY.

Office of the New York State Comptroller. (ndc). Annual Market Value Survey. Albany, NY.

Plummer, E. (2009). Fairness and distributional issues. In R. F. Dye & R. W. England (Eds.), Land value taxation: Theory, evidence, and practice (pp. 73–98). Lincoln Institute of Land Policy.

Plummer, E. (2014). The effects of property tax protests on the assessment uniformity of residential properties. Real Estate Economics., 42(4), 900–937.

Ricardo, D. (1817). On the principles of political economy and taxation. John Murray.

Ross, J., & Yan, W. (2013). Fiscal illusion from property reassessment? An empirical test of the residual view. National Tax Journal, 66(1), 7–32.

Sant’Anna, P. H. C., & Zhao, J. (2020). Doubly robust difference-in-differences estimators. Journal of Econometrics, 219(1), 101–122.

Sjoquist, D. L., & Walker, M. B. (1999). Economies of scale in property tax assessment. National Tax Journal, 52(2), 207–220.

Sun, L., & Abraham, S. (2021). Estimating dynamic treatment effects in event studies with heterogeneous treatment effects. Journal of Econometrics, 222(2), 175–199.

Törnqvist, L., Vartia, P., & Vartia, Y. O. (1985). How should relative changes be measured? The American Statistician, 39(1), 43–46.

Wooldridge, J. M. (2015). Control function methods in applied econometrics. Journal of Human Resources, 50(2), 420–445.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Tables

9,

10,

11, Figs.

New York Sample, Event study estimates (Double Robust estimator): Annual cycle. Note: Standard errors are estimated using wild bootstrap with 999 repetitions. The treated units are 209 assessing jurisdictions in NY that conducted annual reassessment for at least six consecutive years between 2000 and 2016, while the comparison group is consisted of 293 jurisdictions that reassessed less frequently than once every six years since 1970. *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1

7,

New York Sample, Event study estimates (Double Robust estimator): Triennial cycle. Note: Standard errors are estimated using wild bootstrap with 999 repetitions. The treated units are assessing jurisdictions in NY that conducted triennial assessment for at least two consecutive cycles between 2000 and 2016, while the comparison group is consisted of 293 jurisdictions that reassessed less frequently than once every six years since 1970. *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, Y., Hou, Y. Property Valuation – Cycle Length and Assessment Outcome. J Real Estate Finan Econ (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11146-023-09975-8

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11146-023-09975-8