Abstract

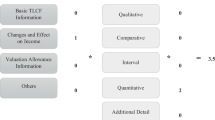

Nonrecurring income taxes are transitory items that exclusively affect earnings through tax expense. We conduct the first in-depth examination of nonrecurring income taxes to determine whether they are primarily attributable to economic events or managerial opportunism. We find that nonrecurring income taxes have little predictive power for future earnings, are not associated with meeting or beating analyst earnings forecasts, and are not associated with future tax expense restatements. We also provide descriptive information about the tax events that frequently result in nonrecurring income taxes and find that the most common events are tax audit resolutions, valuation allowance changes, tax law changes, mergers, and repatriations. Overall, our findings suggest that nonrecurring income taxes are driven by economics rather than opportunism. We recommend that researchers consider whether the inclusion of nonrecurring income taxes (or specific types of nonrecurring taxes) is appropriate when using effective tax rate levels or volatility as measures of tax risk, avoidance, or aggressiveness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Even for country-level events such as tax law changes, outsiders frequently need guidance from management to understand firm-level effects (Plumlee 2003).

APB 28 itself does not mention discrete items. Rather, the qualifications and dissenting opinions recommend accounting for each interim period as a discrete period. See comments by Messrs Norr, Halvorson, Hayes, and Watt.

Section 30-7 specifies that the estimated annual ETR applied to ordinary income or loss shall exclude “tax related to significant unusual or infrequently occurring items that will be separately reported.” Thus, firms often separately disclose the tax effect of special items because the tax effect on unusual or infrequently occurring items is not part of the estimated annual ETR. However, the tax effect of special items is not included in nonrecurring income taxes.

Compustat began collecting NRTAX in 2001, but the variable is not well-populated until 2005, when many firms disclosed repatriation taxes due to the American Jobs Creation Act of 2005.

In an early version of this study, we randomly selected 400 firms with nonzero NRTAX between 2005 and 2012 and hand-collected the reasons these firms had NRTAX for all firm-quarters between 2005 and 2012. In this version, we expanded our hand-collection of NRTAX reasons to 2005–2017 Q3 for the original 400 firms.

Appendix 2 provides examples of firm disclosures of valuation allowance releases.

For about 30% of quarterly observations, we cannot determine the dollar amounts related to specific issues. Special items are similarly difficult to classify. Johnson et al. (2011) find that 25% of special items from 2001 to 2009 are classified in Compustat’s “other” subcategory.

We follow Cain et al. (2019) and adjust annual variables to quarterly when data are available. Returnsq-1,q equals the stock returns from the end of quarter q-1 to quarter q, and Returnsq-4,q-1 equals the stock returns from the end of quarter q-4 to quarter q-1. ΔBTMq-4,q equals the change in book-to-market ratio. ΔROAq-4,q equals the change in return on assets. Mergery-1 equals 1 if the firm has M&A activity (positive AQS) in year y-1 or y-2, and 0 otherwise. EmployeeDecy-1 equals 1 if the number of employees (EMP) declines from year y-2 to y-1, and 0 otherwise. DiscOpy-1 equals 1 if the firm has discontinued operations (DO), and 0 otherwise. LargeSalesDecq-4,q equals 1 if the firm is in the bottom quintile of sales growth from quarter q-4 to quarter q of its industry-year, and 0 otherwise. ΔSaleq-4,q equals the percent change in sales from quarter q-4 to quarter q. Lossq equals 1 if pretax earnings are less than zero, and 0 otherwise. PctLossq-8,q-1 equals the number of quarters with negative pretax earnings from quarter q-8 to quarter q-1 divided by eight. ΔCFOy-2,y-1 equals the change in cash flows from operations (OANCF minus XIDOC, scaled by net sales). OpCycley-1 equals the operating cycle in year y-1 calculated as the log-transformed sum of days inventory outstanding and receivables outstanding. CapitalIntensityy-1 equals property, plant, and equipment (PPENT). IntangibleIntensityy-1 equals intangible assets (INTAN). Ln(Assetsq) equals the log of total assets at the end of the quarter.

In untabulated analysis, we test whether current financial statement data predicts the next quarter’s NRTAX. We find explanatory power from deferred tax assets, PRE, tax loss carryforwards, pretax losses, employee declines, capital intensity, and intangible intensity for future NRTAX. We no longer find an association between quarterly ETR changes and future NRTAX, so ETR changes do not appear useful in predicting future NRTAX. The explanatory power for the future NRTAX amount is poor relative to its power for the contemporaneous NRTAX amount, although many variables remain significant. Historical financial information weakly predicts the amount of future nonrecurring income taxes. In contrast to the explanatory power that reached 18% for explaining the current quarterly amount of NRTAX, the explanatory power is only 1.1% for explaining the next quarter’s NRTAX amount.

For each cross-validation fold, the sample is randomly split into ten equal-sized subsamples with nine subsamples pooled to train the model and one subsample used as a holdout sample to evaluate the model’s performance. Thus, the model’s performance is evaluated ten times for each fold, as each of the ten subsamples serves as a holdout subsample. Sampling the fold ten times gives 100 cross-validation runs.

We calculate each cross-validation run’s AUC by computing the area under the ROC curve with the TPR and FPR for each cutoff percentile from 50 to 100% incremented by 1%.

We test the null hypothesis that the average AUC equals 0.50, which is the AUC of a random classification scheme with corrected resampled t-statistics following Larcker and Zakolyukina (2012).

We present performance at these cutoffs because the annual NRTAX frequency ranges between 4 and 8% (Panel B, Table 1) and quarterly NRTAX frequency ranges between 3 and 13% (untabulated).

For comparison, we examine the validity of the SPI incidence model. As special items are more frequent (55% of firm-quarters have SPI), we randomly select half of the sample to train the SPI incidence model, and examine model performance on the holdout sample. Using a logistic regression, we classify firm-quarters with a likelihood value greater than 0.5 as having SPI. The AUC is 0.73, the TPR is 74%, the FPR is 40%, precision is 69%, and accuracy is 67%. At cutoff likelihood value 0.7, the TPR is 38%, the FPR is 12%, precision is 79%, and accuracy is 60%. These values reflect that the SPI model also has difficulty identifying special items.

In the 24 firm-quarters we found to have NRTAX items, we found seven valuation allowance changes, six tax audit resolutions, two foreign earning repatriations, three restructuring-related tax items, two accounting-related tax items, three unspecified discrete items, and one firm-quarter with a tax audit resolution and valuation allowance change.

Of the 43 firm-quarters for which we could identify why Compustat recorded NRTAX items, we found 12 tax audit resolutions, eight valuation allowance changes, seven repatriations, five deferred tax audit write-offs, four unspecified discrete items, three tax law changes, two tax authority rulings, one restructuring, and one firm with a tax audit resolution and valuation allowance change.

For SPI, we also examine 25 firm-quarters from both situations when the model and Compustat disagree on the existence of quarterly SPI (for comparison). We cannot identify an event or reason why Compustat records an SPI for five of the 25 firm-quarters when our model does not identify an SPI. When Compustat does not record an SPI but the model identifies one, we find that 12 of the 25 firm-quarters have what appear to be special items (e.g., settlements or restructuring charges). Overall, Compustat’s SPI collection is very similar to Compustat’s NRTAX collection.

In the annual NRTAX model, columns 2 and 4 exclude the annual loss indicator because changes in annual ETRs and cash ETRs are set to missing for annual loss firm-years. The quarterly NRTAX model in Panel A includes the quarterly pretax loss indicator, as the ETR denominator is the year-to-date pretax earnings.

We test the magnitude of coefficients on SPI and NRTAX by creating a negative NRTAX variable equal to NRTAX times negative one. Using this variable instead of NRTAX in Eq. 2, we test the equality of coefficients for SPI and NRTAX.

Consistent with Kolev et al. (2008), Curtis et al. (2014), Doyle et al. (2003), and Hsu and Kross (2011), we find a negative association between special items and future earnings. However, other studies document a positive association between special items and future earnings (Chen 2010; Gu and Chen 2004; Jones and Smith 2011).

We combine NRTAX from error/method changes, court rulings, and tax refunds with the “other” category because these types have less than 20 observations.

We examine whether the association between stock returns and NRTAX depends on firm information environments as proxied by average quarterly bid-ask spread and residual analyst coverage (Hong, Lim, and Stein 2007), where firms with below (above) median values of bid-ask spread (coverage) are strong information environments. We do not find significant differences in the association between NRTAX and three-day stock returns around the earnings announcement based on the quality of the information environment (untabulated).

We also do not find significant differences in the association between NRTAX and quarterly stock returns based on the information environment quality, except for in quarters 1–3, where firms with above median residual analyst following have a significantly greater association between NRTAX and quarterly stock returns than firms with below median residual analyst following (untabulated).

After adding annual changes in GAAP and cash ETRs as explanatory variables, NRTAX is not significantly associated with annual stock returns. However, these variables reduce the sample size by 30%, as ETRs require positive pretax earnings and, in this reduced sample, NRTAX is not significantly associated with returns even when excluding the ETRs. We conclude that NRTAX adds information for firms with negative pretax earnings.

Cash ETR equals taxes paid divided by pretax income minus special items. Cash ETR adjusted for NRTAX equals taxes paid plus nonrecurring income taxes divided by pretax income minus special items. Although some NRTAX events will not have an immediate impact on cash flows, other NRTAX events potentially do (e.g., tax audit resolutions and earnings repatriations). GAAP ETR equals tax expense divided by pretax income minus special items. GAAP ETR adjusted for NRTAX equals tax expense plus nonrecurring income taxes divided by pretax income minus special items. To calculate a meaningful ETR, we require the numerator and denominator for the ETR to be positive. For comparison, we keep the sample consistent by excluding observations missing data for any ETR calculation.

Repatriations often generate income-decreasing NRTAX and cash outflows. Other identified NRTAX items typically generate income increases and may or may not have cash effects. In untabulated analyses, we adjust cash ETR only for the income-decreasing NRTAX and consider the volatility of cash ETR. Similar to row 2, we observe the lowest frequency of NRTAX in the lowest decile of cash ETR volatility, and the middle deciles have 19–20% frequency. Thus, we conclude that adjusting cash ETR for NRTAX lowers volatility.

We assume NRTAX reported in the TCJA enactment quarter are attributable to TCJA. To validate this, we randomly select 20 U.S. corporations and match NRTAX to the earnings release disclosures about TCJA effects. We obtain 19 out of 20 matches between firm disclosures of TCJA impact on tax expense and Compustat’s NRTAX. For the firm that did not match, Compustat aggregated other nonrecurring income taxes with the effect of TCJA.

References

Audit Analytics. 2018. Long-term trends in non-GAAP disclosures. https://www.auditanalytics.com/blog/long-term-trends-in-non-gaap-disclosures-a-three-year-overview/. Accessed 5 Feb 2019.

Ayers, Benjamin C., Casey M. Schwab, and Steven Utke. 2015. Noncompliance with mandatory disclosure requirements: The magnitude and determinants of undisclosed permanently reinvested earnings. The Accounting Review 90 (1): 59–93.

Bauman, Christine C., Mark P. Bauman, and Robert F. Halsey. 2001. Do firms use the deferred tax asset valuation allowance to manage earnings? Journal of American Taxation Association 23: 27–48.

Bens, Daniel A., and Rick Johnston. 2010. Accounting discretion: Use or abuse? An analysis of restructuring charges surrounding regulator action. Contemporary Accounting Research 26 (3): 673–699.

Black, Dirk E., and Theodore E. Christensen. 2009. U.S. Managers’ use of ‘pro forma’ adjustments to meet strategic earnings targets. Journal of Business, Finance and Accounting 36: 297–326.

Black, Ervin L., Theodore E. Christensen, Paraskevi V. Kiosse, and Thomas D. Steffen. 2017. Has the regulation of non-GAAP disclosures influenced managers’ use of aggressive earnings exclusions? Journal of Business, Finance and Accounting 32: 209–240.

Black, Dirk E., Theodore E. Christensen, Jack T. Ciesielski, and Benjamin C. Whipple. 2018. Non-GAAP reporting: Evidence from academia and current practice. Journal of Business, Finance and Accounting 45: 259–294.

Black, Dirk E., Thoedore E. Christensen, Jack T. Ciesielski, and Benjamin C. Whipple. 2021. Non-GAAP earnings: A consistency and comparability crisis? Contemporary Accounting Research 38 (3): 1712–1747.

Blouin, Jennifer, and Linda Krull. 2009. Bringing it home: A study of the incentives surrounding the repatriation of foreign earnings under the American Jobs Creation Act of 2004. Journal of Accounting Research 47: 1027–1059.

Bratten, Brian, Cristi Gleason, Stephannie A. Larocque, and Lillian F. Mills. 2017. Forecasting taxes: New evidence from analysts. The Accounting Review 92: 1–19.

Brown, Lawrence D., and Arianna S. Pinello. 2007. To what extent does the financial reporting process curb earnings surprise games? Journal of Accounting Research 45 (5): 947–981.

Burgstahler, David, James Jiambalvo, and Terry Shevlin. 2002. Do stock prices fully reflect the implications of special items for future earnings? Journal of Accounting Research 40: 585–612.

Cain, Carol A., Kalin S. Kolev, and Sarah McVay. 2019. Detecting opportunistic special items. Management Science 66 (5): 1783–2290.

Cazier, Richard, Sonja Rego, **aoli Tian, and Ryan Wilson. 2015. The impact of increased disclosure requirements and the standardization of accounting practices on earnings management through the reserve for income taxes. Review of Accounting Studies 20: 436–469.

Chen, Chi-Ying. 2010. Do analysts and investors fully understand the persistence of the items excluded from Street earnings? Review of Accounting Studies 15: 32–69.

Chen, Kevin CW., and Michael P. Schoderbek. 2000. The 1993 tax rate increase and deferred tax adjustments: A test of functional fixation. Journal of Accounting Research 38: 23–44.

Chen, Novia X., Sabrina Chi, and Terry J. Shevlin. 2020. A Tale of two forecasts: An analysis of mandatory and voluntary effective tax rate forecasts. Working paper, University of Houston. Available at: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3271837. Accessed 18 June 2021.

Christensen, Theodore E., Michael S. Drake, and Jacob R. Thornock. 2014. Optimistic reporting and pessimistic investing: Do pro forma earnings disclosures attract short sellers? Contemporary Accounting Review 31: 67–102.

Comprix, Joseph, Lillian F. Mills, and Andrew P. Schmidt. 2012. Bias in quarterly estimates of annual effective tax rates and earnings management. Journal of American Taxation Association 34: 31–53.

Cready, William, Thomas Lopez, and Craig Sisneros. 2010. The persistence and market valuation of recurring nonrecurring items. The Accounting Review 85: 1577–1615.

Cready, William, Thomas Lopez, and Craig Sisneros. 2012. Negative special items and future earnings: Expense transfer or real improvements. The Accounting Review 87: 1165–1195.

Curtis, Asher, Sarah McVay, and Benjamin C. Whipple. 2014. The disclosure of non-GAAP earnings information in the presence of transitory gains. The Accounting Review 89: 933–958.

Dhaliwal, Dan S., Cristi A. Gleason, and Lillian F. Mills. 2004. Last-chance earnings management: Using the tax expense to meet analysts’ forecasts. Contemporary Accounting Research 21: 431–459.

Dhaliwal, Dan S., Steven E. Kaplan, Rick C. Laux, and Eric Weisbrod. 2013. The information content of tax expense for firms reporting losses. Journal of Accounting Research 51: 135–164.

Donelson, Dain C., Ross Jennings, and John McInnis. 2011. Changes over time in the revenue-expense relation: Accounting or economics? The Accounting Review 86: 945–974.

Doyle, Jeffrey T., Russell J. Lundholm, and Mark T. Soliman. 2003. The predictive value of expenses excluded from pro forma earnings. Review of Accounting Studies 8: 145–174.

Doyle, Jeffrey T., Jared N. Jennings, and Mark T. Soliman. 2013. Do managers define non-GAAP earnings to meet or beat analyst forecasts? Journal of Accounting and Economics 56: 40–56.

Dyreng, Scott D., Michelle Hanlon, and Edward L. Maydew. 2008. Long-run corporate tax avoidance. The Accounting Review 83 (1): 61–82.

Dyreng, Scott D., and Bradley P. Lindsey. 2009. Using financial accounting data to examine the effect of foreign operations located in tax havens and other countries on U.S. multinational firms’ tax rates. Journal of Accounting Research 47: 1283–1316.

Dyreng, Scott D., Bradley P. Lindsey, and Jacob R. Thornock. 2013. Exploring the role Delaware plays as a domestic tax haven. Journal of Financial Economics 108: 751–772.

Ehinger, Anne C., Joshua A. Lee, B. Stomberg, and Erin Towery. 2020. The relative importance of tax reporting complexity and IRS scrutiny in voluntary tax disclosure decisions. Working paper, Florida State University. Available at: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3009390. Accessed 18 June 2021.

Fairfield, P., Karen Kitching, and T. Tang. 2009. Are special items informative about future profit margins? Review of Accounting Studies 14: 204–236.

Frank, Mary M., and Sonja O. Rego. 2006. Do managers use the valuation allowance account to manage earnings around certain earnings targets? The Journal of the American Taxation Association 28: 43–65.

Frankel, Richard. 2009. Discussion of “Are special items informative about future profit margins?” Review of Accounting Studies 14: 237–245.

Graham, John R., and Lillian F. Mills. 2008. Using tax return data to simulate corporate marginal tax rates. Journal of Accounting and Economics 46: 366–388.

Graham, John R., Jana S. Raedy, and Douglas A. Shackelford. 2012. Research in accounting for income taxes. Journal of Accounting and Economics 53: 412–434.

Gu, Zhaoyang, and Ting Chen. 2004. Analysts’ treatment of nonrecurring items in street earnings. Journal of Accounting and Economics 38: 129–170.

Guenther, David, Steven Matsunaga, and Brian Williams. 2017. Is tax avoidance related to firm risk? The Accounting Review 92: 115–136.

Gupta, Sanjay, Rick Laux, and Daniel Lynch. 2016. Do firms use tax reserves to meet analysts’ forecasts? Evidence from the pre- and post-FIN 48 periods. Contemporary Accounting Research 33: 1044–1074.

Hanlon, Michelle, Lillian F. Mills, and Joel Slemrod. 2007. An empirical examination of big business tax noncompliance. In Taxing Corporate Income in the 21st Century, ed. A. Auerbach, J.R. Hines, and J. Slemrod, 171–210. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hanlon, Michelle, Edward L. Maydew, and Daniel Saavedra. 2017. The taxman cometh: Does tax uncertainty affect corporate cash holdings? Review of Accounting Studies 22 (3): 1198–1228.

Harford, Jarrad. 1999. Corporate cash reserves and acquisitions. Journal of Finance 54: 1969–1997.

Hong, Harrison, Terence Lim, and Jeremy C. Stein. 2007. Bad news travels slowly: Size, analyst coverage, and the profitability of momentum strategies. Journal of Finance 55: 265–295.

Hoopes, Jeffrey. 2018. Financial accounting consequences of temporary tax law: Evidence from the R&D tax credit. Working paper, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Available at: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2671935. Accessed 16 Apr 2020.

Hoopes, Jeffrey, Devan Mescall, and Jeffrey A. Pittman. 2012. Do IRS audits deter corporate tax avoidance? The Accounting Review 87: 1603–1639.

Hsu, Charles, and William Kross. 2011. The market pricing of special items that are included in versus excluded from Street earnings. Contemporary Accounting Research 28: 990–1017.

Johnson, Peter M., Thomas J. Lopez, and Juan M. Sanchez. 2011. Special items: A descriptive analysis. Accounting Horizons 25: 511–536.

Jones, Denise, and Kimberly Smith. 2011. Comparing the value relevance, predictive value, and persistence of other comprehensive income and special items. The Accounting Review 86: 2047–2073.

Kolev, Kalin, Carol A. Marquardt, and Sarah E. McVay. 2008. SEC Scrutiny and the evolution of non-GAAP reporting. The Accounting Review 83: 157–184.

Koutney, Colin Q. 2021. Analyst forecast accuracy when deviating from manager’s voluntary annual effective tax rate forecast. Working Paper, George Mason University. Available at: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3259579. Accessed 10 Dec 2021.

Kravet, Todd D., Frank Murphy, and Sarah Parsons. 2019. Determinants and consequences of nonproprietary voluntary disclosure. Working Paper, University of Connecticut. Available at: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3389970. Accessed 6 July 2021.

Krull, Linda K. 2004. Permanently reinvested foreign earnings, taxes, and earnings management. The Accounting Review 79: 745–767.

Larcker, David F., and Anastasia A. Zakolyukina. 2012. Detecting deceptive discussions in conference calls. Journal of Accounting Research 50 (2): 495–540.

Mauler, Landon M. 2019. The effect of analysts’ disaggregated forecasts on investors and managers: Evidence using pre-tax forecasts. The Accounting Review 94: 279–302.

McVay, Sarah E. 2006. Earnings management using classification shifting: An examination of core earnings and special items. The Accounting Review 81: 501–531.

Mills, Lillian. 1998. Book-tax differences and Internal Revenue Service audit adjustments. Journal of Accounting Research 36: 343–356.

Mills, Lillian, Kaye Newberry, and Garth Novack. 2003. How well do Compustat NOL data identify firms with U.S. tax return loss carryovers? Journal of the American Taxation Association 25: 1–17.

Plumlee, Marlene. 2003. The effect of information complexity on analysts’ use of that information. The Accounting Review 78: 275–296.

Riedl, Edward J., and Suraj Srinivasan. 2010. Signaling firm performance through financial statement presentation: An analysis using special items. Contemporary Accounting Research 27: 289–332.

Schrand, Catherine M., and M.H.F. Wong. 2003. Earnings management using the valuation allowance for deferred tax assets under SFAS No. 109. Contemporary Accounting Research 20: 579–611.

Towery, Erin M. 2017. Unintended consequences of linking tax return disclosures to financial reporting for income taxes: Evidence from Schedule UTP. The Accounting Review 92 (5): 201–226.

Wagner, Alexander F., Richard J. Zeckhauser, and Alexandre Ziegler. 2018. Unequal rewards to firms: Stock market responses to the Trump election and the 2017 corporate tax reform. American Economic Association Papers and Proceedings 108: 590–596.

Wagner, Alexander F., Richard J. Zeckhauser, and Alexandre Ziegler. 2018. Company stock price reactions to the 2016 election shock: Trump, taxes and trade. Journal of Financial Economics 130: 428–451.

Weber, David P. 2009. Do analysts and investors fully appreciate the implications of book-tax differences for future earnings? Contemporary Accounting Review 26 (4): 1175–1206.

Acknowledgements

We thank Kathleen Andries, Brad Badertscher, Jennifer Blouin, Mark Bradshaw, Ted Christensen, Shannon Chen, Paul Demere (NTA discussant), Matthew Erickson (AAA discussant), Jeffrey Hoopes, Daehyun Kim, Michael Mayberry (JATA discussant), Kathleen Powers, John Robinson, Brady Williams, **nyu Zhang, and workshop participants at the College of William and Mary, University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign, The Ohio State University, University of Notre Dame, 2016 American Taxation Association Midyear Meeting, 2016 AAA Annual Meeting, 2016 National Tax Association Annual Meeting, WHU Otto-Beisheim School of Management Tax Readings Group, University of Arizona Tax Readings Group, and University of Texas at Austin for comments and suggestions. We also thank Dahlia Elsaadi and Alejandra Flores for their research assistance and the McCombs Research Excellence Fund for financial assistance. Lillian Mills appreciates support from the Beverly H. and William P. O’Hara Chair in Business.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Table 12.

Appendix 2: Example Firm Disclosures of Valuation Allowance Releases

2.1 LeapFrog Enterprises, 4th quarter 2012

Net income in the fourth quarter of 2012 included a tax benefit of $20.3 million, or $0.29 per diluted share, as a result of recording the expected tax benefit of a portion of the company’s past accumulated net operating losses due to improved historical results and future prospects.

2.2 Omnicell, Inc., 4th quarter 2007

Included in fourth quarter net income is $7.0 million, or $0.19 per fully diluted share, income tax benefit related to the partial reversal of the Company’s tax valuation allowance.

2.3 Ethan Allen Interiors, Inc., 3rd quarter 2012

GAAP net income for 2009 was positively affected by a $183.3 million non-cash tax benefit from reversing a portion of the valuation allowance related to the Company’s net operating loss carry forwards. The valuation allowance was reversed to reflect the amount of deferred tax asset that is estimated to be more likely than not to be realized after taking into consideration current operating results and future estimated taxable income.

Appendix 3: Examples of Firm Pre-Announcement of NRTAX

-

1.

Tax Audit Settlement: Harris Corporation 09/22/2006

Harris Corporation increased earnings guidance to reflect a lower tax rate due to a favorable tax audit settlement, which lowered tax expense in the first quarter of 2007 by $12 million.

-

2.

Tax Audit Settlement: Pepsi 12/02/2003

During the fourth quarter, PepsiCo anticipates a tax benefit of approximately $0.07 to $0.08 per share, resulting principally from the conclusion of prior years’ domestic audits, for which a final settlement was reached with the IRS. PepsiCo believes a substantial portion of this tax benefit will offset the investment actions outlined above. As a result of the favorable audit resolution, together with the continuing growth of its international earnings, PepsiCo estimates its effective tax rate for 2004 will be 29.5%.

-

3.

Tax Audit Settlement: Express Scripts Holding Company 10/28/2016

On October 28, 2016, Express Scripts Holding Company (the “Company”) announced the receipt of a letter from the Internal Revenue Service which reported the conclusion of its examination with respect to the potential tax benefit related to the disposition of PolyMedica Corporation (Liberty), as discussed in the Company’s Form 10-Q filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission on October 25, 2016, for which no benefit has been recognized to date. Accordingly, the Company will recognize a net tax benefit of approximately $511 million during the three months ending December 31, 2016. The Company expects this tax benefit to increase its diluted EPS attributable to Express Scripts (as defined in the Company’s press release dated October 25, 2016 relating to, among other things, its fourth quarter and fiscal 2016 guidance (the “Guidance Press Release”)) by $0.80 — $0.81 for the three months and fiscal year ending December 31, 2016 above the guidance it announced in the Guidance Press Release. The Company’s guidance with respect to adjusted diluted earnings per share attributable to Express Scripts as announced in the Guidance Press Release remains unchanged.

-

4.

Restructuring: GenTherm 02/19/2016

As disclosed on January 5, 2016, subsidiaries of Gentherm completed reorganization transactions related to the eventual closure of the Company’s Windsor, Ontario, Canada facility to consolidate the operations of that facility into existing European and North American facilities. The Windsor facility is expected to close permanently in June 2016. Consequently, Gentherm expects to pay a withholding tax in Canada and record a one-time tax expense of approximately $6 million, or $0.16 per diluted share, in the first quarter of 2016.

-

5.

Repatriation: Cognizant 08/05/2016

In May 2016, our principal operating subsidiary in India repurchased shares from its shareholders, which are non-Indian Cognizant entities, resulting in a one-time remittance of $2.8 billion of cash from India. $1.2 billion, or $1.0 billion net of taxes, was transferred to the U.S. with the other $1.6 billion remaining overseas. As a result of this transaction, we will incur an incremental 2016 income tax expense of $237.5 million, of which $190.0 million was recognized in the quarter ended June 30, 2016 and approximately $23.7 million will be recognized in each of the quarters ending September 30, 2016 and December 31, 2016.

-

6.

Form 10-K estimate of changes to UTB: Nike FY 2015

Although the timing of resolution of audits is not certain, the Company evaluates all domestic and foreign audit issues in the aggregate, along with the expiration of applicable statutes of limitations, and estimates that it is reasonably possible the total gross unrecognized tax benefits could decrease by up to $63 million within the next 12 months.

Appendix 4: TCJA

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Donelson, D.C., Koutney, C.Q. & Mills, L.F. Nonrecurring income taxes. Rev Account Stud 29, 1741–1793 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-022-09736-7

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-022-09736-7