Abstract

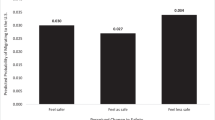

The migration of young men from Mexico to the United States generates a deficit of men and a relative abundance of women in many Mexican communities, but the implications of this imbalanced sex ratio for Mexicans’ risks of criminal victimization has received little attention. We merge individual-level data from 19,551 inhabitants of 136 municipalities covered in the 2002 Mexican Family Life Survey with aggregated data from the 2000 Mexico population census to examine the association between the municipality-level percentage of men at ages 15 to 39 and self-reports of recent violent victimization. Multilevel logistic regression modeling reveals a curvilinear relationship between percent male and the likelihood of experiencing a violent victimization, with victimization risks lowest in municipalities characterized by either unusually low or unusually high numbers of men. Respondents residing in municipalities having a more balanced sex composition experience the highest risk of victimization. The risk of experiencing a violent victimization also varies sharply by age, gender, socioeconomic status, and community characteristics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Over 90% of the incidents fall in the category of “robbery or assault.” The infrequency of other forms of violent offense precludes disaggregation by type of incident.

Online Appendix Table A1 replicates the Table 3 regression models substituting the percent male at ages 15 to 59 for the percent male at ages 15 to 39.

Although it is possible that the MxFLS respondents underreport incidents of violent victimization, we do not consider this missing data in the conventional sense.

Although not technically belonging to a border state, Loreto in Baja California Sur could also be included in this list.

With a value on percent male almost two percentage points higher than the next highest value, La Colorada could be considered an outlier on percent male (Table 1). However, as shown in Online Appendix Table A2 the regression estimates are not affected by the exclusion of respondents living in this municipality.

Online Appendix Table A3 estimates Models 3 and 4 of Table 3 omitting the square of percent male. The coefficient for percent male is small and statistically nonsignificant.

Online Appendix Table A4 estimates the models in Table 3 separately for the women and men MxFLS respondents.

References

Adelman, R., Reid, L. W., Markle, G., Weiss, S., & Jaret, C. (2017). Urban crime rates and the changing face of immigration: Evidence across four decades. Journal of Ethnicity in Criminal Justice, 15, 52–77.

Altman, C. E., Gorman, B. K., & Chávez, S. (2018). Exposure to violence, co** strategies, and diagnosed mental health problems among adults in a migrant-sending community in central Mexico. Population Research and Policy Review, 37, 229–260.

Ancona, S., Dénes, F. V., Krüger, O., Székely, T., & Beissinger, S. R. (2017). Estimating adult sex ratios in nature. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 372, 20160313.

Arnold, F., Kishor, S., & Roy, T. K. (2002). Sex-selective abortions in India. Population and Development Review, 28, 759–785.

Asad, A. L., & Hwang, J. (2019). Indigenous places and the making of undocumented status in Mexico-US migration. International migration Review, 53, 1032–1077.

Barber, N. (2000). The sex ratio as a predictor of cross-national variation in violent crime. Cross-Cultural Research, 34, 264–282.

Barber, N. (2009). Countries with fewer males have more violent crime: Marriage markets and mating aggression. Aggressive Behavior, 35, 49–56.

Bien, C. H., Cai, Y., Emch, M. E., Parish, W., & Tucker, J. D. (2013). High adult sex ratios and risky sexual behaviors: A systematic review. PLoS ONE. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0071580

Bose, S., Trent, K., & South, S. J. (2013). The effect of a male surplus on intimate partner violence in India. Economic & Political Weekly, 48, 53–61.

Brown, R. (2018). The Mexican drug war and early-life health: The impact of violent crime on birth outcomes. Demography, 55, 319–340.

Chaflin, A. (2015). The long-run effect of Mexican immigrants on crime in U.S. cities: Evidence from variation in Mexican fertility rates. American Economic Review, 105, 220–225.

Chiapa, C., & Viejo, J. (2012). Migration, sex ratios and violent crime: Evidence from Mexico’s municipalities [unpublished manuscript].

Croll, E. (2000). Endangered daughters: Discrimination and development in Asia. Routledge.

D’Alessio, S. J., & Stolzenberg, L. (2010). The sex ratio and male-on-female intimate partner violence. Journal of Criminal Justice, 38, 555–561.

Diamond-Smith, N., & Rudolph, K. (2018). The association between uneven sex ratios and violence: Evidence from 6 Asian countries. PloS ONE. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0197516

Donato, K. M. (2010). U.S. migration from Latin America: Gender patterns and shifts. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 630, 78–92.

Donato, K. M., Alexander, J. T., Gabaccia, D. R., & Leionen, J. (2011). Variations in the gender composition of immigrant populations: How they matter. International Migration Review, 45, 495–526.

Drèze, J., & Khera, R. (2000). Crime, gender, and society in India: Insights from homicide data. Population and Development Review, 26, 335–352.

Dyson, T. (2012). Causes and consequences of skewed sex ratios. Annual Review of Sociology, 38, 443–461.

Edlund, L., Li, H., Yi, J., & Zhang, J. (2013). Sex ratios and crime: Evidence from China. Review of Economics and Statistics, 95, 1520–1534.

Filser, A., Barclay, K., Beckley, A., Uggla, C., & Schnettler, S. (2021). Are skewed sex ratios associated with violent crime? A longitudinal analysis using Swedish register data. Evolution and Human Behavior, 42, 212–222.

Grosjean, P., & Khattar, R. (2019). It’s raining men! Hallelujah? The long-run consequences of male-biased sex ratios. The Review of Economic Studies, 86, 723–754.

Guo, G., & Zhao, H. (2000). Multilevel modeling for binary data. Annual Review of Sociology, 26, 441–462.

Guttentag, M., & Secord, P. F. (1983). Too many women? The sex ratio question. Sage.

Hamilton, E. R. (2015). Gendered disparities in Mexico-U.S. migration by class, ethnicity, and geography. Demographic Research, 32, 533–542.

Hesketh, T., & **ng, Z. W. (2006). Abnormal sex ratios in human populations: Causes and consequences. PNAS, 103, 13271–13275.

Hofmann, E. T., & Reiter, E. M. (2018). Geographic variation in sex ratios of the US immigrant population: Identifying sources of difference. Population Research and Policy Review, 37, 485–509.

Hudson, V., & Den Boer, A. M. (2004). Bare branches: The security implications of Asia’s surplus male population. MIT Press.

INEGI. 2020. Retrieved Sept 29, 2020, from http://en.www.inegi.org.mx

King, R. D., Massoglia, M., & MacMillan, R. (2007). The context of marriage and crime: Gender, the propensity to marry, and offending in early adulthood. Criminology, 45, 33–65.

Lloyd, K. M., & South, S. J. (1996). Contextual influences on young men’s transition to first marriage. Social Forces, 74, 1097–1119.

MacDonald, J., & Saunders, J. (2012). Are immigrant youth less violent? Specifying the reasons and mechanisms. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 641, 125–147.

Massey, D. S., Rugh, J. S., & Pren, K. A. (2010). The geography of undocumented Mexican migration. Mexican Studies/estudios Mexicanos, 26, 129–152.

Messner, S. F., & Sampson, R. J. (1991). The sex ratio, family disruption, and rates of violent crime: The paradox of demographic structure. Social Forces, 69, 33–53.

Minnesota Population Center. (2019). Integrated Public Use Microdata Series, International: Version 7.2. IPUMS, 2019. https://doi.org/10.18128/D020.V7.2.

Nivette, A. E. (2011). Cross-national predictors of crime: A meta-analysis. Homicide Studies, 15, 103–131.

Osborne, J. W. (2015). Best practices in logistic regression. Sage.

Parrado, E. A. (2004). International migration and men’s marriage in western Mexico. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 35, 51–75.

Parrado, E. A., & Zenteno, R. M. (2002). Gender differences in union formation in Mexico: Evidence from marital search models. Journal of Marriage and Family, 64, 756–773.

Rafael, S. (2013). International migration, sex ratios, and the socioeconomic outcomes of nonmigrant Mexican women. Demography, 50, 971–991.

Rios Contreras, V. (2014). The role of drug-related violence and extortion in promoting Mexican migration: Unexpected consequences of a drug war. Latin American Research Review, 49, 199–217.

Rubelcava, L. & Teruel, G. (2006). Mexican family life survey, first wave. Mexican Family Life Survey, http://www.ennvih-mxfls.org

Sampson, R. J., Laub, J. H., & Wimer, C. (2006). Does marriage reduce crime? A counterfactual approach to within-individual causal effects. Criminology, 44, 465–508.

Schacht, R., & Kramer, K. L. (2016). Patterns of family formation in response to sex ratio variation. PLoS ONE. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0160320

Schacht, R., Rauch, K. L., & Mulder, M. B. (2014). Too many men: The violence problem? Trends in Ecology and Evolution, 29, 214–222.

Schacht, R., & Smith, K. R. (2017). Causes and consequences of adult sex ratio imbalance in a historical U.S. population. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2016.0314

Schacht, R., Tharp, D., & Smith, K. R. (2016). Marriage markets and male mating effort: Violence and crime are elevated where men are rare. Human Nature, 27, 489–500.

South, S. J., & Messner, S. F. (2000). Crime and demography: Multiple linkages, reciprocal relations. Annual Review of Sociology, 26, 83–106.

South, S. J., Trent, K., & Bose, S. (2012). India’s ‘missing women’ and men’s sexual risk behavior. Population Research and Policy Review, 31, 777–795.

South, S. J., Trent, K., & Bose, S. (2014). Skewed sex ratios and criminal victimization in India. Demography, 51, 1019–1040.

StataCorp. . (2005). Stata statistical software: Release 9.0. Stata Corporation.

Steffensmeier, D., & Allan, E. (1996). Gender and crime: Toward a gendered theory of female offending. Annual Review of Sociology, 22, 459–487.

Stone, E. A. (2017). A test of an evolutionary hypothesis of violence against women: The case of sex ratio. Letters on Evolutionary Behavioral Science, 8, 1–3.

Trent, K., & South, S. J. (2012). Mate availability and women’s sexual experiences in China. Journal of Marriage and Family, 74, 201–214.

Tuljapurkar, S., Li, N., & Feldman, M. W. (1995). High sex ratios in China’s future. Science, 267, 874–876.

Villareal, A., & Yu, W.-H. (2017). Crime, fear, and mental health in Mexico. Criminology, 55, 779–805.

White, K., & Potter, J. E. (2013). The impact of outmigration of men on fertility and marriage in the migrant-sending states of Mexico, 1995–2000. Population Studies, 67, 83–95.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

South, S.J., Han, S. & Trent, K. Imbalanced Sex Ratios and Violent Victimization in Mexico. Popul Res Policy Rev 41, 843–864 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-021-09667-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-021-09667-2