Abstract

Social cognition—the complex mental ability to perceive social stimuli and negotiate the social environment—has emerged as an important cognitive ability needed for social functioning, everyday functioning, and quality of life. Deficits in social cognition have been well documented in those with severe mental illness including schizophrenia and depression, those along the autism spectrum, and those with other brain disorders where such deficits profoundly impact everyday life. Moreover, subtle deficits in social cognition have been observed in other clinical populations, especially those that may have compromised non-social cognition (i.e., fluid intelligence such as memory). Among people living with HIV (PLHIV), 44% experience cognitive impairment; likewise, social cognitive deficits in theory of mind, prosody, empathy, and emotional face recognition/perception are gradually being recognized. This systematic review and meta-analysis aim to summarize the current knowledge of social cognitive ability among PLHIV, identified by 14 studies focused on social cognition among PLHIV, and provides an objective consensus of the findings. In general, the literature suggests that PLHIV may be at-risk of develo** subtle social cognitive deficits that may impact their everyday social functioning and quality of life. The causes of such social cognitive deficits remain unclear, but perhaps develop due to (1) HIV-related sequelae that are damaging the same neurological systems in which social cognition and non-social cognition are processed; (2) stress related to co** with HIV disease itself that overwhelms one’s social cognitive resources; or (3) may have been present pre-morbidly, possibly contributing to an HIV infection. From this, a theoretical framework is proposed highlighting the relationships between social cognition, non-social cognition, and social everyday functioning.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Despite treatment advances making HIV disease a manageable chronic health condition, HIV remains highly distressing and can compromise one’s access to healthcare, social interactions, and quality of life (Turan et al., 2019; Yuvaraj et al., 2020). The preponderance of studies show that social support remains important in buffering against the negative effects of HIV among people living with HIV (PLHIV) (Rzeszutek, 2018; Slater et al., 2013). Yet, an ability that may be pivotal in negotiating the social environment to cultivate such social support is social cognition.

Social cognition—the complex mental ability to perceive, understand, and respond to socially relevant stimuli and navigate the social environment—has emerged as an important ability that subserves efficient social functioning and garners social support in everyday life (Adolphs, 2001). Social cognition is vital to social everyday functioning, from interacting with strangers on the street, making friends and social supports, to maintaining intimate relationships, to bargaining socially and financially, interacting with employees, and detecting threats in one’s social environment. If one is not able to accurately interpret social cues (e.g., facial expression) or others’ mental states (e.g., emotions, intentions, thoughts), especially in a complex social environment surrounded by HIV and within the context of medical care, this can create numerous issues in misunderstanding people, resulting in poor outcomes to the individual. Consistent with this view, a large body of work in clinical psychology and neurological disorders showed that people with schizophrenia (Fett et al., 2011; Green et al., 2015) and autism spectrum disorders (Velikonja et al., 2019), both of which are characterized with marked social dysfunction, demonstrate social cognitive impairments that profoundly impact everyday life. Further, more subtle deficits in social cognition have also been observed in other clinical populations (e.g., adults with mild cognitive impairment; alcohol use disorder) which can also exert difficulty in social relationships that impair social everyday functioning and quality of life (Bora & Yener, 2017; Le Berre, 2019). Below, we briefly present representative social cognitive constructs relevant to this discussion, specifically in emotional face recognition/perception, prosody perception, theory of mind, and empathy.

Facial emotional recognition/perception (i.e., affective face perception) is the most studied social cognitive construct both in social neuroscience and clinical neuroscience (Beaudoin & Beauchamp, 2020). Non-affective face perception involves the perception of structural cues from facial stimuli (e.g., discriminating older faces from younger faces, selecting female faces from male faces). Affective face perception involves the perception of affective information garnered from facial stimuli. Affective face perception can be assessed directly or indirectly. Typical tasks that indirectly measure affective face perception ask participants to discriminate older from younger faces or female from male faces while presenting faces with emotional expressions. In this way, emotional expression of face stimuli is not relevant to the task goal, but its effect on performance can be assessed. Typical tasks that directly assess affective face perception ask participants to perceive emotional quality of faces (e.g., happy, sad, angry). Most paradigms on affective face perception primarily employed static (i.e., not moving) face stimuli that show canonical facial expression, rather than dynamic facial stimuli that express subtle and changing emotions, like facial expressions that are typically encountered in everyday life. Emerging studies suggest that PLHIV may experience some mild impairment in emotional facial recognition (Clark et al., 2010, 2015); if so, this could impair their ability to negotiate their social environment, an environment where some may misperceive threat or acceptance.

Prosody perception involves an ability to perceive emotions that are conveyed through acoustic properties of voices (e.g., pitch, intonation) (Jasmin et al., 2021). Like affective face perception, prosody perception can be assessed indirectly or directly by either making emotional quality of voices task-relevant or not. Within the context of HIV, emerging studies suggest PLHIV also experience poorer prosody compared to controls (González-Baeza et al., 2017).

Theory of mind refers to an ability to take perspectives of other people and infer their mental states, such as belief, thought, or intention (Beaudoin & Beauchamp, 2020; Carlson et al., 2013). Theory of mind is also known as mentalizing or mental state attribution. Theory of mind can be assessed with a range of stimuli including cartoons, vignettes, or videos. After being presented with these stimuli, a participant is asked to infer belief or intention of another person whose perspective may or may not differ from the perspective of the participant. Within the context of HIV, preliminary evidence suggests that PLHIV may exhibit comparable impairments in this ability as those with schizophrenia (Lysaker et al., 2012). Also, such poorer theory of mind ability has been linked to more inclination to engage in risky health behaviors (Walzer et al., 2016).

Empathy broadly refers to an ability to share and understand emotional states of other people and includes affect sharing and empathic accuracy (Beaudoin & Beauchamp, 2020; Decety, 2010). Affect sharing involves an ability to share emotional states of another person (e.g., feeling pain when looking at a picture depicting a person being hurt in a car accident) and typically does not involve inferential processes. To the contrary, empathic accuracy involves an ability to accurately infer emotional states of other people. A typical paradigm on empathic accuracy asks a participant to continuously rate the emotional states of another person (i.e., a target) while watching a brief clip that depicts a target describing an autobiographical event and assesses empathic accuracy by examining the correspondence between a participant’s rating and a target’s own rating (Lee et al., 2011). In addition to these paradigms, self-report questionnaires have also been used to assess the subjective evaluation of empathic experiences. For instance, the Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI) (Davis, 1980) is composed of four subscales, each assessing different facets of empathy. Within the context of HIV, very little is known about empathy, but what little is known suggests a link between empathy and the propensity to engage less in risky health behaviors (Walzer et al., 2016).

Deficits in social cognition are gradually being recognized in PLHIV (Baldonero et al., 2013; Grabyan et al., 2018). The reasons for the development of such deficits are unclear, but perhaps they are due to (1) compromised non-social cognitive functioning, that is fluid cognitive abilities (i.e., executive function, memory), common in PLHIV that impact the same neurological systems in which social cognition is processed, or (2) stress related to co** with the HIV infection itself that overwhelms one’s social cognitive resources. In fact, it is conceivable that some PLWH may have had premorbid social cognitive deficits that may have contributed to their HIV infection. The purpose of this systematic review and meta-analysis of social cognition in the context of HIV was to examine and summarize the existing literature and provide an objective consensus of the findings. A synthesis of the findings and an examination of the methodology was provided to recommend the next steps to propel the science in this area. Based on the results of this systematic review and meta-analysis, a rudimentary theoretical framework has been proposed in which to enhance our understanding of how social cognition relates to non-social cognition and social everyday functioning, with an emphasis on how it fits into the larger HIV literature. Implications for practice and research are posited.

Systematic Review of Social Cognition in the Context of HIV Infection

Systematic Review Methodology

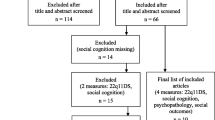

Using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) approach (Moher et al., 2009), MEDLINE (via PubMed) on June 23, 2022, and Embase and Scopus databases on July 12, 2022, were searched for research studies on social cognition in PLHIV (Fig.1). Full search strategies and terms from each database (e.g., theory of mind) are provided in Table 1. From this, 1031 records were identified, and 443 duplicates were removed, leaving 588 records to be reviewed. As it took us time to process and summarize these data, the search was rerun in the three databases on November 9, 2022, to capture any new publications that had been published since the original search date. A total of 33 new references were captured and added to Covidence for screening. Using the Covidence software, two of the authors (JL & DEV) reviewed these article titles, abstracts, and articles separately to determine whether the article met study inclusion criteria. More precisely, the articles (in English) were evaluated for the following inclusion criteria: (1) original research studies in adult humans (not systematic reviews, review articles, or case reports); (2) examination of any social cognition construct using performance tasks (i.e., emotional face recognition/perception, prosody, theory of mind, and empathy) and/or survey; and (3) participant sample must include PLHIV. Studies not meeting these inclusion criteria were excluded. More specific exclusion criteria included (1) focus entirely on emotional regulation without using performance tasks or survey; (2) focus entirely on metacognition; and/or (3) focus on children living with HIV. We (two of the authors who reviewed each article independently) compared their findings of the selected studies and discussed each one until a consensus was met on whether the article met the criteria. In evaluating which studies met criteria, some studies may appear to meet the eligibility criteria, but on further examination, the elements needed for this systematic review were not found. For example, in an article by Schulte et al. (2011), researchers were examining disruption of emotion and conflict processing in HIV infection with and without alcoholism comorbidity. These researchers were using emotionally salient words and faces to examine how this disrupts cognitive functioning. Although emotionally salient faces were used, emotional face recognition/perception was not being examined or measured; thus, such studies like this were excluded. For studies that did meet the eligibility criteria, data items were extract from the articles that met criteria; data items entailed the study characteristics (i.e., sample size, sample characteristics, design), instrument used to measure a particular social cognitive ability, related cognitive findings, major findings, and study strengths/limitations as detailed in Tables 2 and 3. These tables served as an effective method to collect and summarize the data by being able to tabulate and examining findings.

Summaries

Of the studies (n = 14) that met the criteria, most examined facial emotion recognition/perception, followed by two theory of mind studies, one prosody (vocal emotion processing) study, and one empathy study; three of these studies examined more than one type of social cognition. Yet, many of these studies also examined several variables that predicted the performance in these social cognition constructs including non-social cognition, volume of brain regions, EEG, biological sex, and early life trauma. The articles are summarized in alphabetical order by the article’s first author in Appendix as well as in Table 2 grouped by type of social cognitive domain.

Systematic Review Synthesis of Findings

Based on the systematic review, from these studies, converging evidence suggests that some PLHIV may experience mild to moderate deficits in social cognition, which are influenced by early life trauma, biological sex, and sometimes non-social cognitive functioning. Regarding facial emotion recognition/perception, compared to a control group (without HIV), PLHIV were found to be less accurate and/or slower in identifying emotional valence of faces in seven studies (Baldonero et al., 2013; Clark et al., 2010, 2015; González-Baeza et al., 2017; Grabyan et al., 2018; Heilman et al., 2013; Homer et al., 2013; Lane et al., 2012). Difficulty with facial emotion recognition/perception was observed across the spectrum of basic emotions (i.e., anger, fear, disgust, happiness, sadness, surprise); however, more difficulty with recognizing/perceiving faces with negative emotional content was particularly noted in several of these studies (Baldonero et al., 2013; Clark et al., 2010, 2015; González-Baeza et al., 2017; Lane et al., 2012). In two studies in which PLHIV served as a control group with medical adversity (Lysaker et al., 2012, 2014), those with schizophrenia performed worse on facial emotion recognition/perception tasks, but they were not statistically different; this suggests that some PLHIV may be functioning at a similar level as those with schizophrenia who have well documented deficits in social cognition (Green et al., 2015, 2019; Mier & Kirsch, 2017).

Focusing further on facial emotion recognition/perception, predictors of poor performance of PLHIV included early life trauma, neurobiological factors, and non-social cognition. Both Kamkwalala et al. (2021) and Rubin et al. (2022a, b) observed that those with early life trauma experienced more difficulty in facial emotion recognition/perception tasks. The findings from the Kamkwalala et al. (2021) study suggest that this pattern may be more prominent for fearful faces in women living with HIV who did not report early life trauma. As a pharmacologic challenge with placebo vs low dose hydrocortisone, Kamkwalala et al. (2021) also found that low dose hydrocortisone enhanced threat detection of fearful faces, but only in women; within women, the effect was more prominent in women with severe early life trauma. This suggests that the HPA axis plays a role in fearful face recognition in women (specifically with severe early life trauma), but this hydrocortisone effect was blunted in general for men. Further, Rubin et al. (2022a, b) observed those with early life trauma had higher oxytocin levels; and those with early life trauma with low oxytocin and C-reactive protein levels performed worse on the Facial Emotion Perception Test. Further, those with higher levels of myeloid migrations (i.e., MCP-1, MMP-9), regardless of early life trauma, performed worse on total recognition accuracy including happy, angry, sad, fearful, and neutral faces. These findings suggest that those with higher HPA axis hormones performed worse on total facial emotion recognition accuracy than those without early life trauma who have more normal oxytocin levels.

Brain circuitry and non-social cognition undoubtedly influence the social cognition of facial emotion recognition/perception to some degree. Clark et al. (2015) observed that compared to those without HIV, PLHIV had larger amygdala volumes and smaller anterior cingulate cortex volumes; furthermore, recognizing fearful expressions was associated with reduced anterior cingulate cortex volumes. Coupled with the HPA connections as described by Kamkwalala et al. (2021) and Rubin et al. (2022a, b), this suggests neurological involvement with social cognitive impairments, consistent with the potential effect of HIV pathogenesis on brain health (Waldrop et al., 2021). Several studies also examined the effect of non-social cognition on social cognition in PLHIV. Nine studies on the facial emotion recognition/perception included measures of non-social cognition. Four out of nine studies found that poorer non-social cognition was related to poorer facial emotion recognition/perception (Clark et al., 2010; Grabyan et al., 2018; Heilman et al., 2013; Lane et al., 2012); one found no association (González-Baeza et al., 2016); and two found mixed results (Baldonero et al., 2013; Kamkwalala et al., 2021). For example, Baldonero et al. (2013) compared PLHIV with (28.6%) and without (65.3%) non-social cognitive impairment and found no group differences on fear recognition, but they did find that poorer verbal recall/memory was related to poorer fear recognition and overall non-social cognitive ability was related to poorer recognition of happiness. With these findings, the evidence converges that non-social cognition likely plays a role in facial emotion recognition/perception. However, as non-social cognition was not consistently assessed across studies, and the major non-social cognitive domains (e.g., verbal memory, executive functioning) were not always represented in the non-social cognitive batteries, it remains unclear whether social cognitive impairments of PLHIV are entirely explained by non-social cognitive impairments. This overall pattern of findings mirrors the larger social cognitive literature (Rubin et al., 2022a, b).

Prosody perception was represented in only one study. Using a prosody test composed of nine different auditory sentences that were emotionally ladened (i.e., sadness, anger, happiness, fear, neutral), González-Baeza et al. (2017) found PLHIV performed worse on the vocal prosody test than controls. While PLHIV without HAND and controls showed comparable performance on the prosody perception task, PLHIV with HAND performed significantly worse on prosody than healthy controls. Better prosody scores were also associated with larger brain volumes in the left hippocampus, right temporal and parietal lobes, and right thalamus. This study of prosody perception suggests that deficits in prosody perception in PLHIV may be influenced by poorer non-social cognition.

Theory of mind was represented in three very different studies. Homer et al. (2013) examined both theory of mind and facial emotion recognition/perception in those with or without methamphetamine use and those living with or without HIV. Both methamphetamine use and PLHIV performed worse on the facial emotion recognition/perception test than those who do not use methamphetamine and those living without HIV, respectively. Regarding the Faux Pas Task (a theory of mind test), there was a significant main effect in that methamphetamine users performed worse than methamphetamine non-users. While PLHIV also performed worse on the Faux Pas Task than those living without HIV, this difference was not statistically significant. Further, the interaction between methamphetamine use and HIV status on the Faux Pas Task was not significant. The other theory of mind study by Lysaker et al. (2012) found that in comparison to those with schizophrenia, PLHIV performed significantly better on the theory of mind test (Hinting test) and a metacognition test (Metacognition Assessment Scale); however, on a measure of facial emotion recognition/perception (BLERT), there were no group differences. Overall, these studies suggest there may be some minor deficits in theory of mind for PLHIV, but without more studies with control groups, it is difficult to draw any firm conclusion.

Empathy was assessed in only one study. Walzer et al. (2016) observed that those with more empathy (i.e., other focused perspectives) were less likely to engage in risky behaviors that could have an impact on others. Unfortunately, this was a single group study that did not include any control comparison group and employed only a self-report questionnaire. Thus, further studies are needed to better understand whether PLHIV show impaired empathy or not.

In these 14 studies on social cognition, the impact on social everyday functioning was rarely examined. Clark et al. (2010) found that poorer facial emotion recognition/perception of anger was significantly associated with more distress in maintaining a sense of social connectedness. Grabyan et al. (2018) found in PLHIV that accuracy in facial emotion recognitive/perception was related to social ability (i.e., Communication subscale task of the UCSD Performance-based Skills Assessment-Brief). These two studies demonstrate that aspects of social cognition impact everyday social activity, as would be expected. It will be important for future studies to assess diverse aspects of social functioning, including objective social isolation (i.e., social network size, the diversity of social network), subjective social isolation (i.e., quality of social network, loneliness), and integration into a social support system, and map out the extent to which social cognition affects social functioning in PLWH.

Meta-Analysis of Social Cognition in the Context of HIV Infection

To quantify social cognitive performance of PLWH compared to people living without HIV, we conducted a meta-analysis using a correlated effects model. Among relevant studies reviewed above (also see Table 2), eight studies were qualified for this analysis, as all of them included PLWH and people living without HIV, administered at least one social cognitive measure, and provided effect sizes on the group difference or necessary information to calculate effect sizes (e.g., the mean and standard deviation of two groups, or reported the effect size). Studies that did not include a control group of people living with HIV and did not employ a performance task on social cognition were not included in meta-analysis as this can limit how the data can be combined (i.e., data need to be gathered in similar ways for the results to be meaningful). See Table 2 for study characteristics and effects sizes of included studies in the meta-analyses. As some studies reported more than one effect size using the same sample, the single-level meta-analysis approach that assumes independence of effect sizes is not appropriate. Thus, we decided to fit a correlated effects model using the robust variance estimation (RVE) framework with an adjustment for small sample size (Hedges et al., 2010; Pustejovsky & Tipton, 2022; Tipton, 2015). The proportion of heterogeneity associated with differences between studies was evaluated with the I2 statistic. All analyses were performed using the R implementation of these algorithms in the robumeta package Fisher and Tipton (2015).

For this analysis, eight studies provided 12 observed effect sizes between two groups: nine effect sizes on facial affect perception, one effect size on prosody perception, and two effect sizes on theory of mind. Specifically, Gonzelez-Baeza et al. (2016) provided four effect sizes on facial affect perception and Homer et al. (2013) provided two effect sizes on theory of mind. All the other studies provided one effect size. Across eight studies, the estimated effect size between two groups was 0.305 (95% confidence interval: 0.108, 0.502) (see Fig. 2 for details). We did not find evidence of excessive heterogeneity between studies (I2 = 26, T2 = 0.02) (see Fig. 3).

In addition, we conducted another meta-analysis on facial affect perception alone. Across the six studies reporting facial affect perception the estimated effect size was 0.24 3 (95% confidence interval: − 0.016, 0.502, I2 = 27, T2 = 0.02) (see Fig. 2). We suspect that this result is due to the outlier results of Baldonero et al. (2013) in this subset of studies. While these findings indicate that overall PLWH show impaired social cognitive performance compared to people living without HIV, this finding should be considered in the context of a small number of studies that were included in this analysis and the limited scope of included social cognitive domains.

Discussion

Methodologically, these social cognition studies in the context of HIV infection have distinct and overlap** features that influence the quality of the data and the conclusions derived from them. Such features include the types of social cognitive domains measured, sample size, adequacy of control group(s), study design, inclusion of a non-social neuropsychological test battery, inclusion of neurological measures (e.g., biomarkers, MRI), inclusion of social everyday outcome measures (i.e., social networks, social communication), and other influential factors (i.e., substance use). To guide this methodological synthesis, Table 3 highlights the limitations of these 14 studies, thus indicating emerging growth opportunities for the social cognition HIV literature.

Social Cognition Measures

Social cognitive ability is generally assessed through measures of facial emotion recognition/perception, prosody, theory of mind, and empathy. In our systematic review, social cognition is represented in 12 facial emotion recognition/perception studies, two theory of mind studies, one prosody study, and one empathy study, with some overlap in domains in two studies. One study on empathy employed a self-report questionnaire, rather than using a performance task. For a more complete picture of social cognition in the context of HIV infection, studies are needed that assess all the main social cognitive concepts and corresponding measures within the same study, to determine whether each social cognitive domain is similarly affected among PLHIV or not, and the extent to which each social cognitive domain is related to other domains.

Sample Size

Samples sizes for these studies ranged from 56 to 217 (i.e., 56, 58, 65, 65, 69, 79, 83, 88, 100, 110, 121, 146, 147, 217). As such, these studies were adequately powered to satisfy the central limit theorem needed for most general statistical analyses. Half were under 100, as such there is some concern that such limited sample sizes may reduce their generalizability and ecological validity. As few studies report power analyses, none of the studies reported whether they were adequately powered or not; however, several reported effect sizes (Grabyan et al., 2018; Heilman et al., 2013; Homer et al., 2013; Kamkwalala et al., 2021; Lane et al., 2012; Rubin et al., 2022a, b). Ultimately, small sample sizes prohibit our ability to carefully examine the role of biological variables and social categories on social cognition in PLHIV (e.g., age, sex assigned at birth, gender identity, sexual identity).

Control Group Adequacy

Most (13 out of 14) studies had some sort of control/comparison group, which provided a context to the findings. Nine of these provided a comparison with people living without HIV which provides an adequate control group to infer the effect of HIV infection on social cognitive processes. Sex differences in PLHIV were examined in one study (i.e., Kamkwalala et al., 2021); although this study did not include the HIV-negative comparison, it was laudable to compare performance between men and women as sex differences on social cognitive processes have been observed in other populations (Ferrer-Quintero et al., 2021; Proverbio, 2023). Likewise, Rubin et al. (2022a, b) compared those with and without early life trauma in PLHIV; this provided a unique comparison on an obvious important variable related to social cognition (Rokita et al., 2020). Two studies (Lysaker et al., 2012, 2014) employed PLHIV as a control group for those with schizophrenia; it is harder to interpret these findings within a larger context, but it did provide a unique comparison to a population that has well documented deficits in social cognition (Lee et al., 2013; Mier & Kirsch, 2017).

Study Design

These studies were all cross-sectional protocols; although the Kamkwalala et al. (2021) study was a placebo-controlled cross-over study. Thus, we do not know whether social cognitive processes in PLHIV are stable or change over time. As non-social cognition in PLHIV often vacillates over time (Vance et al., 2022), social cognition may also vacillate depending on a host of factors such as how well one learns to cope with medical adversity, changes in cognition, and mood. Thus, it is important to document the durability of social cognitive functioning overtime in longitudinally designed studies.

Non-Social Neuropsychological Assessment

Ten out of 14 studies assessed non-social cognition to some degree (six with full non-social neuropsychological test batteries). Some studies suggest a connection between social cognition and non-social cognition (Clark et al., 2010; Grabyan et al., 2018; Heilman et al., 2013; Lane et al., 2012), one found no connection (González-Baeza et al., 2016), and two found mixed results (Baldonero et al., 2018; Kamkwalala et al., 2021). Thus, social cognitive ability is related to non-social cognitive ability to some degree in PLHIV, a pattern reflective of what has been shown in other populations (Cella et al., 2015) but not all (i.e., schizophrenia, Rubin et al., 2022a, b). Future studies are needed to determine the extent to which non-social cognitive impairments explain social cognitive impairments in PLHIV. Further, none of the studies (Table 3) included measures of subjective non-social cognition such as self-rated non-social cognitive health. NeuroHIV studies vary as to whether subjective non-social cognition may or may not be related to objective non-social neuropsychological test performance (Jacob et al., 2022; Vance et al., 2008); that is, sometimes people may not be aware of their non-social cognitive impairments or may perceive they have cognitive impairments when in fact, they are performing normally. From a social cognitive perspective, if one is experiencing such non-social cognitive impairments, this could hinder their ability to pick up on social cues. On the other hand, if one is worried about having such non-social cognitive impairments, he or she may be uncomfortable being around others or concerned about kee** up with conversations, which could lead to social withdraw. It is unclear from the literature how both objective and subjective non-social cognition interact to affect social cognition. Moving forward, to gain a better understanding of these potential relationships, researchers should consider including both an objective non-social cognitive performance battery as well as a subjective non-social cognitive battery into their protocols.

Neurological Measures

Neuroimaging or other psychophysical measures (i.e., MRI) were conducted in only five studies. Yet of those, all found significant connections with social cognition. As these studies examined the relationship between brain structure and social cognitive ability, it remains unknown whether functional abnormalities in the brain are related to social cognitive performance in PLHIV. Future studies with functional magnetic resonance imaging [fMRI] may provide valuable information about the neural mechanisms related to social cognitive processes in PLHIV. Only two studies included biomarkers in their study protocols. As certain biomarkers are related to non-social cognition, it is likely many have important associations with social cognition. Rubin et al. (2022a, b) observed that the myeloid migration (MCP-1/MMP-9) factor was associated with reduced facial emotion perception accuracy. Furthermore, instead of examining a standard panel of biomarkers and examining their relationship with social cognition, Kamkwalala et al. (2021) used a novel mechanistic probe (i.e., 10 mg of hydrocortisone) to examine its effect on social cognition, specifically facial emotion recognition/perception. This novel approach implicated a role for the HPA axis in social cognition. The field can advance by examining such biomarkers in studies focusing on social cognition.

Social Everyday Function

From a practical implication perspective, the evaluation of such social cognitive deficits on social everyday functioning (i.e., isolation, building supportive social networks) remains at the center of this research. Studies in social cognitive research indicate that deficits in social cognition impact social network size, loneliness, and isolation (Beaudoin & Beauchamp, 2020; Eramudugolla et al., 2022). Two studies in this systematic review examined such social everyday outcomes. Clark et al. (2010) found that poorer facial emotion recognition of anger was significantly associated with more distress in not being able to maintain a sense of social connectedness. More specifically, Clark et al. (2010) showed that difficulty in identifying anger was moderately related to self-reported difficulties in intimate social relationships. Similarly, Grabyan et al. (2018) observed that poorer accuracy of facial emotion recognition/perception predicted social cognitive ability. These promising findings indicate that it will be important to examine the relationship between social cognitive ability and social functioning in a systematic way. For instance, it will be important to separate objective social connection (e.g., the number of social relationships, the extent of social networks) from subjective social connection (e.g., loneliness). It will be also important to include other key determinants (e.g., depression) to map the pathways between non-social cognitive ability and social cognition functioning, which could identify the most promising targets for interventions.

Future Research Implications

Several important future research implications were provided specifically above to strengthen the rigor (i.e., increasing sample size) and direction (e.g., longitudinally designed studies to assess changes in social cognition over time) in this area. Albeit, others require further consideration. First, within this systematic/meta-analysis article, there is an implicit assumption that the neurophysiology of HIV or the psychosocial dynamics of experiencing HIV compromise social cognitive abilities. Yet, it is also likely that premorbid social cognitive deficits may have contributed to one’s HIV infection, and thus the sample of PLHIV may already be a group predisposed to such social cognitive deficits. Unfortunately, methodologically disentangling this requires assessing social cognitive abilities before and after being infected and diagnosed with HIV. Obviously, there is not a simple way to collect such data as it would require administering such social cognitive tests to a large sample of people and wait to see which ones become infected with HIV, and then follow up to see if social cognition changes. Yet, one way to do this would be to employ such social cognitive assessments in large cohort studies such as the MWCCS (Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study/Women’s Interagency HIV Study—Combined Cohort Study) which longitudinally follows large numbers of men and women with HIV and at-risk for HIV. The advantage of the MWCCS studies is that they also gather data on non-social cognition and social everyday functioning (Vance et al., 2016).

A second direction worth further exploration is intervention studies. Intervention studies were not identified in this systematic review; despite some deficits observed in PLHIV, no studies provided an intervention to target deficits in social cognition. Perhaps with the focus on social cognition in the context of HIV infection being a relatively untapped vector of research, it is unclear how profound and/or impactful such deficits in social cognition are to warrant an intervention. If such an intervention was to be provided, three treatment vectors could be examined. First, some evidence suggests that social cognition is more dependent on non-social cognition; for example, González-Baeza et al. (2017) found that vocal prosody was significantly worse in those with HAND than controls, while those PLHIV with normal cognitive functioning performed similarly to controls. Thus, interventions that improve non-social cognition, such as computerized non-social cognitive training (e.g., speed of processing training; Vance et al., 2019), could potentially improve aspects of social cognition as well. Second, social cognitive training programs have been administered to individuals with schizophrenia with some moderate improvements observed (Horan et al., 2018; Lindenmayer et al., 2018; Nahum et al., 2021). As such an approach could be adapted for PLHIV, it will be important to systematically examine the pathways that social cognitive processes affect daily functioning and health-related outcomes in PLHIV. It is possible that social cognitive processes may affect health-related outcomes independent of non-social cognitive impairments. It is also possible that social cognition moderates the relationships between other important factors (i.e., communication with healthcare providers) and health-related outcomes. And third, based on the work by Kamkwalala et al. (2021) and Rubin et al. (2022a, b), low dose hydrocortisone over a 28-day period may be a way to improve social cognition as well as non-social cognition in PLHIV (NCT03237689; R01MH113512).

Thirdly, another area of research is to catalog and map the neuroanatomical substrates and hormonal substrates required for normal social cognition, and then examine how HIV compromises each of these neuroanatomical and hormonal substrates. To do so, one would have to examine this for each type of social cognition (i.e., prosody, empathy, theory of mind, emotional face recognition/perception). For example, clearly prosody which requires auditory processing would require different neuroanatomical and hormonal substrates than emotional face recognition/perception which requires visual processing. For example, the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) is associated with emotional face recognition/perception, but the ACC is known to be differentially affected in PLHIV; in fact, Clark et al. (2015) found that reduced ACC volume in PLHIW was correlated with fear recognition impairments. Such cataloging of these substrates from the existing literature will also be needed to advance the neuroHIV social cognition literature.

And finally, HIV medications may have a direct or indirect impact on social cognition. It is well-known that many of the legacy HIV medications can have a detrimental impact on brain health and cognition (Dumond et al., 2020; Spence et al., 2022); although these social cognitive HIV studies did not investigate this, it is conceivable that these medications could have negatively impacted social cognition as well. Similarly, many of these legacy HIV medications were also known to have severe side effects (i.e., diarrhea, chronic fatigue, abdominal distress) that could impact one’s ability to socialize; thus, indirectly they could have a dynamic impact on social cognition as well. Moving forward, studies in this area should consider the role in which HIV medications, especially the legacy medications, exert on social cognition.

Theoretical Implications

From this systematic review and meta-analysis, a rudimentary framework in which to conceptualize the major concepts is proposed in which social cognition is embedded in the larger HIV literature (Fig. 4). We posit that for the field of social cognition to develop in this clinical population, we must examine the interrelationships between social cognition, non-social cognition, and social everyday functioning. Social everyday functioning serves as the target outcome. Social network size is part of the objective social isolation and social network quality is part of the subjective social isolation. Social support can be viewed as part of subjective social isolation. This proposed framework is by no means exhaustive, but it provides a starting point to encourage further discussions and research in this area for PLHIV.

Social Cognition and Non-Social Cognition (Path A)

From the larger social cognition field, the literature shows a mild to moderate connection between social cognition and non-social cognition (Kubota et al., 2022; Seo et al., 2020). For example, in a sample of 131 adults with early onset schizophrenia, Kubota et al. (2022) found that higher scores on theory of mind was significantly related to higher scores on verbal fluency in women, while higher scores on theory of mind was significantly related to higher scores on executive functioning in men. This relationship has been observed in other measures of social cognition such as facial emotion recognition/perception (Seo et al., 2020).

As shown in our systematic review among studies including PLHIV, the relationship between social cognition and non-social cognition is clearly mixed; in fact, some of these findings may be confounded by the task itself (i.e., emotional processing tasks required quick response time). Yet, given these limitations, of the studies that assessed non-social cognition, cautiously most (7 out of 10) found a mild to moderate association (e.g., Clark et al., 2010; Grabyan et al., 2018; Heilman et al., 2013; Lane et al., 2012). This suggests some of the same neural circuitry for processing social cognition may overlap as non-social cognitive processing, and/or such social cognition is partially dependent on non-social cognitive processing. Thus, as the brain is impacted by HIV pathogenesis or other factors (i.e., drug use, depression, trauma, aging), both social cognition and non-social cognition are compromised together. Yet, as nearly 44% of PLHIV experience HAND (Wei et al., 2020) and with the aging of the HIV population, concerns mount that non-social cognition will be increasingly compromised by age-related comorbidities (Waldrop et al., 2021), as such social cognition may also be partially compromised.

Social Cognition and Social Everyday Functioning (Path B)

Social cognition plays a key role in social everyday functioning of various populations. Better social cognition is related to better social integration of people in general (Stiller & Dunbar, 2007), and particularly among individuals with alcohol use disorder (Lewis et al., 2019), and individuals with dementia (Eramudugolla et al., 2022). Better social cognition predicts better daily functioning, beyond what has been explained by non-social cognition (Fett et al., 2011; Hoertnagl et al., 2011). Social cognition also mediates the relationship between non-social cognition and daily functioning in individuals with severe mental illness, suggesting that social cognition is a proximal target for improving daily functioning. While most studies on the role of social cognition in daily functioning focus on social integration (i.e., social isolation), emerging evidence from research among people living with substance use disorder suggests the role of social cognition in treatment adherence. Impaired social cognitive performance of individuals with alcohol use disorder was related to poor treatment adherence (Foisy et al., 2007; Rupp et al., 2017).

In this systematic review among studies including PLHIV, only two studies examined the impact of social cognition on social everyday functioning (Clark et al., 2010; Grabyan et al., 2018). Both found that facial emotion recognition/perception was related to (1) a sense of social connectedness, and (2) social ability. Moving forward, HIV studies that examine social everyday functioning should also include outcomes relevant in which social cognition would be critical, such as negotiating interactions with clinicians, medication adherence, and adherence to clinic appointments.

Non-Social Cognition and Social Everyday Functioning (Path C)

Studies show that a strong relationship exists between non-social cognition and social everyday functioning (i.e., perceived isolation, social network size) (Nie et al., 2021). For example, in a Spanish nationally representative sample of older adults (50 + ; N = 1691), Lara et al. (2019) found that over a 3-year period, decreased non-social cognitive function was associated with both social isolation and loneliness. However, as discussed earlier, decreased social interaction may likewise impact non-social cognitive health (Cacioppo & Cacioppo, 2014; Noonan et al., 2018). The non-social cognitive aging literature is filled with such examples (Kelly et al., 2017). Unfortunately, the HIV literature holds very few examples. In a sample of 370 Black and White older adults living with and without HIV, Han et al. (2017) found that poorer non-social cognitive functioning was related to greater loneliness among older Black adults living with HIV. Although more HIV research is needed on this topic, based on the larger literature, it seems likely that there is a dynamic reciprocal relationship between non-social cognition and social everyday functioning among PLHIV.

Integration and Other Factors

The conceptual framework proposed (Fig. 4) links the main concepts of social cognition, non-social cognition, and social everyday functioning. It is important to note that there are integrative and other factors that may have contributed to being infected with HIV that also impact the relationships between these three concepts. Clearly, the social determinants of health (i.e., access to healthcare, lifetime discrimination) and psychosocial factors (i.e., depression, early lifetime trauma, substance use, stigma) can mediate/moderate the relationships between these key concepts (Halpin et al., 2020; Thompson et al., 2022; Vance, 2013). For instance, the presence or absence of early trauma (Rubin et al., 2022a, b), meth use (Homer et al., 2013), or any of these other factors can impact performance on these social cognition tests. In the context of HIV infection, these social determinants of health and psychosocial factors have been shown to play an important role in all aspects of life including overall health, quality of life, and mortality. For example, depression alone, with a prevalence of 31% in PLHIV (Rezaei et al., 2019), can clearly impact non-social cognition (Waldrop et al., 2021) and interact with social cognition and social everyday functioning. As our knowledge of these relationships emerges between these three basic concepts, this framework will need to be challenged and expanded to incorporate other clinically relevant factors.

Conclusion

Collectively, based on our systematic review and meta-analysis, these studies suggest that some PLHIV, especially if they have some non-social cognitive impairments, experience subclinical deficiencies in understanding, processing, or describing social stimuli. Such poorer social cognition could lead to more social isolation and decreased social support. As this is an emerging area of HIV research, it is not surprising that there are not social cognitive interventions developed yet.

Data Availability

References

Adolphs, R. (2001). The neurobiology of social cognition. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 11(2), 231–239. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0959-4388(00)00202-6

Baldonero, E., Ciccarelli, N., Fabbiani, M., Colafigli, M., Improta, E., D’Avino, A., Mondi, A., Cauda, R., Di Giambenedetto, S., & Silveri, M. C. (2013). Evaluation of emotion processing in HIV-infected patients and correlation with cognitive performance. BMC Psychology, 1(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.1186/2050-7283-1-3

Baron-Cohen, S., Wheelwright, S., Hill, J., Raste, Y., & Plumb, I. (2001). The “Reading the mind in the eyes” Test revised version: A study with normal adults, and adults with Asperger syndrome or high-functioning autism. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 42, 241–251. https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-7610.00715

Beaudoin, C., & Beauchamp, M. H. (2020). Social cognition. Handbook of Clinical Neurology, 173, 255–264. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-64150-2.00022-8

Bora, E., & Yener, G. G. (2017). Meta-analysis of social cognition in mild cognitive impairment. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology, 30(4), 206–213. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891988717710337

Bowers, D., Blonder, L., & Heilman, K. (1991). The Florida affect battery. University of Florida.

Cacioppo, J. T., & Cacioppo, S. (2014). Older adults reporting social isolation or loneliness show poorer cognitive function 4 years later. Evidence-Based Nursing, 17(2), 59–60. https://doi.org/10.1136/eb-2013-101379

Carlson, S. M., Koenig, M. A., & Harms, M. B. (2013). Theory of mind. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews. Cognitive Science, 4(4), 391–402. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcs.1232

Cella, M., Hamid, S., Butt, K., & Wykes, T. (2015). Cognition and social cognition in non-psychotic siblings of patients with schizophrenia. Cognitive Neuropsychiatry, 20(3), 232–242. https://doi.org/10.1080/13546805.2015.1014032

Clark, U. S., Cohen, R. A., Westbrook, M. L., Devlin, K. N., & Tashima, K. T. (2010). Facial emotion recognition impairments in individuals with HIV. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 16(6), 1127–1137. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1355617710001037

Clark, U. S., Walker, K. A., Cohen, R. A., Devlin, K. N., Folkers, A. M., Pina, M. J., & Tashima, K. T. (2015). Facial emotion recognition impairments are associated with brain volume abnormalities in individuals with HIV. Neuropsychologia, 70, 263–271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2015.03.003

Davis, M. H. (1980). A multidimensional approach to individual differences in empathy. JASAS Catalog Selected Doc Psychol, 10, 85–104.

Decety, J. (2010). The neurodevelopment of empathy in humans. Developmental Neuroscience, 32(4), 257–267. https://doi.org/10.1159/000317771

Dumond, J. B., Bay, C. P., Nelson, J. A. E., Davalos, A., Edmonds, A., De Paris, K., Sykes, C., Anastos, K., Sharma, R., Kassaye, S., Tamraz, B., French, A. L., Gange, S., Ofotokun, I., Fischl, M. A., Vance, D. E., & Adimora, A. A. (2020). Intracellular tenofovir and emtricitabine concentrations in younger and older women with HIV receiving tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 64(9), e00177-e220. https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.00177-20

Ekman, P., & Friesen, W. V. (1976). Pictures of facial affect. Consulting Psychologists Press.

Eramudugolla, R., Huynh, K., Zhou, S., Amos, J. G., & Anstey, K. J. (2022). Social cognition and social functioning in MCI and dementia in an epidemiological sample. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 28(7), 661–672. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1355617721000898

Ferrer-Quintero, M., Green, M. F., Horan, W. P., Penn, D. L., Kern, R. S., & Lee, J. (2021). The effect of sex on social cognition and functioning in schizophrenia. NPJ Schizophrenia, 7(1), 57. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41537-021-00188-7

Fett, A. K., Viechtbauer, W., Dominguez, M. D., Penn, D. L., van Os, J., & Krabbendam, L. (2011). The relationship between neurocognition and social cognition with functional outcomes in schizophrenia: A meta-analysis. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 35(3), 573–588. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.07.001

Fisher, Z. F., & Tipton, E. (2015). robumeta: An R-package for robust variance estimation in meta-analysis. ar**v:Methodology

Foisy, M. L., Kornreich, C., Fobe, A., D’Hondt, L., Pelc, I., Hanak, C., Verbanck, P., & Philippot, P. (2007). Impaired emotional facial expression recognition in alcohol dependence: Do these deficits persist with midterm abstinence? Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 31(3), 404–410. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00321.x

González-Baeza, A., Arribas, J. R., Pérez-Valero, I., Monge, S., Bayón, C., Martín, P., Rubio, S., & Carvajal, F. (2017). Vocal emotion processing deficits in HIV-infected individuals. Journal of Neurovirology, 23(2), 304–312. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13365-016-0501-0

González-Baeza, A., Carvajal, F., Bayón, C., Pérez-Valero, I., Montes-Ramírez, M., & Arribas, J. R. (2016). Facial emotion processing in aviremic HIV-infected adults. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 31(5), 401–410. https://doi.org/10.1093/arclin/acw023

Grabyan, J. M., Morgan, E. E., Cameron, M. V., Villalobos, J., Grant, I., Woods, S. P., & the HIV Neurobehavioral Research Program (HNRP) Group. (2018). Deficient emotion processing is associated with everyday functioning capacity in HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 33(2), 184–193. https://doi.org/10.1093/arclin/acx058

Green, M. F., Horan, W. P., & Lee, J. (2015). Social cognition in schizophrenia. Nature Reviews. Neuroscience, 16(10), 620–631. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn4005

Green, M. F., Horan, W. P., & Lee, J. (2019). Nonsocial and social cognition in schizophrenia: Current evidence and future directions. World Psychiatry, 18(2), 146–161. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20624

Gur, R. C., Ragland, J. D., Moberg, P. J., Turner, T. H., Bilker, W. B., Kohler, C., Siegel, S. J., & Gur, R. E. (2001). Computerized neurocognitive scanning: I. Methodology and validation in healthy people. Neuropsychopharmacology, 25(5), 766–776. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00278-0

Halpin, S. N., Ge, L., Mehta, C. C., Gustafson, D., Robertson, K. R., Rubin, L. H., Sharma, A., Vance, D., Valcour, V., Waldrop-Valverde, D., & Ofotokun, I. (2020). Psychosocial resources and emotions in women living with HIV who have cognitive impairment: Applying the Socio-Emotional Adaptation Theory. Research and Theory for Nursing Practice, 34(1), 49–64. https://doi.org/10.1891/1541-6577.34.1.49

Han, S. D., Adeyemi, O., Wilson, R. S., Leurgans, S., Jimenez, A., Oullet, L., Shah, R., Landay, A., Bennett, D. A., & Barnes, L. L. (2017). Loneliness in older Black adults with human immunodeficiency virus is associated with poorer cognition. Gerontology, 63(3), 253–262. https://doi.org/10.1159/000455253

Hedges, L. V., Tipton, E., & Johnson, M. C. (2010). Robust variance estimation in meta-regression with dependent effect size estimates. Research Synthesis Methods, 1(1), 39–65. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.5

Heilman, K. J., Harden, E. R., Weber, K. M., Cohen, M., & Porges, S. W. (2013). Atypical autonomic regulation, auditory processing, and affect recognition in women with HIV. Biological Psychology, 94(1), 143–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2013.06.003

Hoertnagl, C. M., Muehlbacher, M., Biedermann, F., Yalcin, N., Baumgartner, S., Schwitzer, G., Deisenhammer, E. A., Hausmann, A., Kemmler, G., Benecke, C., & Hofer, A. (2011). Facial emotion recognition and its relationship to subjective and functional outcomes in remitted patients with bipolar I disorder. Bipolar Disorders, 13(5–6), 537–544. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-5618.2011.00947.x

Homer, B. D., Halkitis, P. N., Moeller, R. W., & Solomon, T. M. (2013). Methamphetamine use and HIV in relation to social cognition. Journal of Health Psychology, 18(7), 900–910. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105312457802

Horan, W. P., Dolinsky, M., Lee, J., Kern, R. S., Hellemann, G., Sugar, C. A., Glynn, S. M., & Green, M. F. (2018). Social cognitive skills training for psychosis with community-based training exercises: A randomized controlled trial. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 44(6), 1254–1266. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbx167

Horowitz, L. M., Rosenberg, S. E., Baer, B. A., Ureño, G., & Villaseñor, V. S. (1988). Inventory of interpersonal problems: Psychometric properties and clinical applications. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 56(6), 885–892. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006x.56.6.885

Ipser, J. C., Brown, G. G., Bischoff-Grethe, A., Connolly, C. G., Ellis, R. J., Heaton, R. K., Grant, I., & Translational Methamphetamine AIDS Research Center (TMARC) Group. (2015). HIV infection is associated with attenuated frontostriatal intrinsic connectivity: A preliminary study. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 21(3), 203–213. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1355617715000156

Jacob, A., Fazeli, P. L., Crowe, M. G., & Vance, D. E. (2022). Correlates of subjective and objective everyday functioning in middle-aged and older adults with HIV. Applied Neuropsychology: Adult. https://doi.org/10.1097/JNC.0000000000000339

Jasmin, K., Dick, F., & Tierney, A. T. (2021). The multidimensional battery of prosody perception (MBOPP). Wellcome Open Research, 5, 4. https://doi.org/10.12688/wellcomeopenres.15607.2

Kamkwalala, A. R., Maki, P. M., Langenecker, S. A., Phan, K. L., Weber, K. M., & Rubin, L. H. (2021). Sex-specific effects of low-dose hydrocortisone on threat detection in HIV. Journal of Neurovirology, 27(5), 716–726. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13365-021-01007-6

Kelly, M. E., Duff, H., Kelly, S., McHugh Power, J. E., Brennan, S., Lawlor, B. A., & Loughrey, D. G. (2017). The impact of social activities, social networks, social support and social relationships on the cognitive functioning of healthy older adults: A systematic review. Systematic Reviews, 6(1), 259. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-017-0632-2

Kubota, R., Okubo, R., Ikezawa, S., Matsui, M., Adachi, L., Wada, A., Fujimaki, C., Yamada, Y., Saeki, K., Sumiyoshi, C., Kikuchi, A., Omachi, Y., Takeda, K., Hashimoto, R., Sumiyoshi, T., & Yoshimura, N. (2022). Sex differences in social cognition and association of social cognition and neurocognition in early course schizophrenia. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 867468. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.867468

Lane, T. A., Moore, D. M., Batchelor, J., Brew, B. J., & Cysique, L. A. (2012). Facial emotional processing in HIV infection: Relation to neurocognitive and neuropsychiatric status. Neuropsychology, 26(6), 713–722. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029964

Langenecker, S. A., Bieliauskas, L. A., Rapport, L. J., Zubieta, J. K., Wilde, E. A., & Berent, S. (2005). Face emotion perception and executive functioning deficits in depression. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology, 27(3), 320–333. https://doi.org/10.1080/13803390490490515720

Lara, E., Caballero, F. F., Rico-Uribe, L. A., Olaya, B., Haro, J. M., Ayuso-Mateos, J. L., & Miret, M. (2019). Are loneliness and social isolation associated with cognitive decline? International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 34(11), 1613–1622. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.5174

Le Berre, A. P. (2019). Emotional processing and social cognition in alcohol use disorder. Neuropsychology, 33(6), 808–821. https://doi.org/10.1037/neu0000572

Lee, J., Altshuler, L., Glahn, D. C., Miklowitz, D. J., Ochsner, K., & Green, M. F. (2013). Social and nonsocial cognition in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia: Relative levels of impairment. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 170(3), 334–341. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12040490

Lee, J., Zaki, J., Harvey, P. O., Ochsner, K., & Green, M. F. (2011). Schizophrenia patients are impaired in empathic accuracy. Psychological Medicine, 41(11), 2297–2304. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291711000614

Lewis, B., Price, J. L., Garcia, C. C., & Nixon, S. J. (2019). Emotional face processing among treatment-seeking individuals with alcohol use disorders: Investigating sex differences and relationships with interpersonal functioning. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 54(4), 361–369. https://doi.org/10.1093/alcalc/agz010

Lindenmayer, J. P., Khan, A., McGurk, S. R., Kulsa, M., Ljuri, I., Ozog, V., Fregenti, S., Capodilupo, G., Buccellato, K., Thanju, A., Goldring, A., Parak, M., & Parker, B. (2018). Does social cognition training augment response to computer-assisted cognitive remediation for schizophrenia? Schizophrenia Research, 201, 180–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2018.06.012

Lysaker, P. H., Ringer, J. M., Buck, K. D., Grant, M., Olesek, K., Leudtke, B. L., & Dimaggio, G. (2012). Metacognitive and social cognition deficits in patients with significant psychiatric and medical adversity: A comparison between participants with schizophrenia and a sample of participants who are HIV-positive. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 200(2), 130–134. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0b013e3182439533

Lysaker, P. H., Vohs, J., Hamm, J. A., Kukla, M., Minor, K. S., de Jong, S., van Donkersgoed, R., Pijnenborg, M. H., Kent, J. S., Matthews, S. C., Ringer, J. M., Leonhardt, B. L., Francis, M. M., Buck, K. D., & Dimaggio, G. (2014). Deficits in metacognitive capacity distinguish patients with schizophrenia from those with prolonged medical adversity. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 55, 126–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.04.011

Mier, D., & Kirsch, P. (2017). Social-cognitive deficits in schizophrenia. Current Topics in Behavioral Neurosciences, 30, 397–409. https://doi.org/10.1007/7854_2015_427

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., PRISMA Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA Statement. Open medicine: A peer-reviewed, independent, open-access journal, 3(3), e123–e130.

Nahum, M., Lee, H., Fisher, M., Green, M. F., Hooker, C. I., Ventura, J., Jordan, J. T., Rose, A., Kim, S. J., Haut, K. M., Merzenich, M. M., & Vinogradov, S. (2021). Online social cognition training in schizophrenia: A double-blind, randomized, controlled multi-site clinical trial. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 47(1), 108–117. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbaa085

Nie, Y., Richards, M., Kubinova, R., Titarenko, A., Malyutina, S., Kozela, M., Pajak, A., Bobak, M., & Ruiz, M. (2021). Social networks and cognitive function in older adults: Findings from the HAPIEE study. BMC Geriatrics, 21(1), 570. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-021-02531-0

Noonan, M. P., Mars, R. B., Sallet, J., Dunbar, R. I. M., & Fellows, L. K. (2018). The structural and functional brain networks that support human social networks. Behavioral Brain Research, 355, 12–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbr.2018.02.019

Pinkham, A. E., Harvey, P. D., & Penn, D. L. (2018). Social cognition psychometric evaluation: Results of the Final Validation Study. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 44(4), 737–748. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbx117

Porges, S. W. (2007). The polyvagal perspective. Biological Psychology, 74, 116–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.20006.06.009

Proverbio, A. M. (2023). Sex differences in the social brain and in social cognition. Journal of Neuroscience Research, 101(5), 730–738. https://doi.org/10.1002/jnr.24787

Pustejovsky, J. E., & Tipton. E. (2022). Meta-analysis with robust variance estimation: Expanding the range of working models. Prevention Science, 23(3), 425–438. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-021-01246-3

Rezaei, S., Ahmadi, S., Rahmati, J., Hosseinifard, H., Dehnad, A., Aryankhesal, A., Shabaninejad, H., Ghasemyani, S., Alihosseini, S., Bragazzi, N. L., Raoofi, S., Kiaee, Z. M., & Ghashghaee, A. (2019). Global prevalence of depression in HIV/AIDS: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care, 9(4), 404–412. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjspcare-2019-001952

Rokita, K. I., Holleran, L., Dauvermann, M. R., Mothersill, D., Holland, J., Costello, L., Kane, R., McKernan, D., Morris, D. W., Kelly, J. P., Corvin, A., Hallahan, B., McDonald, C., & Donohoe, G. (2020). Childhood trauma, brain structure and emotion recognition in patients with schizophrenia and healthy participants. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 15(12), 1336–1350. https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsaa160

Rubin, L. H., Bhattacharya, D., Fuchs, J., Matthews, A., Abdellah, S., Veenhuis, R. T., Langenecker, S. A., Weber, K. M., Nazarloo, H. P., Keating, S. M., Carter, C. S., & Maki, P. M. (2022a). Early life trauma and social processing in HIV: The role of neuroendocrine factors and inflammation. Psychosomatic Medicine, 84(8), 874–884. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0000000000001124

Rubin, L. H., Han, J., Coughlin, J. M., Hill, S. K., Bishop, J. R., Tamminga, C. A., Clementz, B. A., Pearlson, G. D., Keshavan, M. S., Gershon, E. S., Heilman, K. J., Porges, S. W., Sweeney, J. A., & Keedy, S. (2022b). Real-time facial emotion recognition deficits across the psychosis spectrum: A B-SNIP Study. Schizophrenia Research, 243, 489–499. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2021.11.027

Rupp, C. I., Derntl, B., Osthaus, F., Kemmler, G., & Fleischhacker, W. W. (2017). Impact of social cognition on alcohol dependence treatment outcome: Poorer facial emotion recognition predicts relapse/dropout. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 41(12), 2197–2206. https://doi.org/10.1111/acer.13522

Rzeszutek, M. (2018). A longitudinal analysis of posttraumatic growth and affective well-being among people living with HIV: The moderating role of received and provided social support. PLoS ONE, 13(8), e0201641. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0201641

Schulte, T., Müller-Oehring, E. M., Sullivan, E. V., & Pfefferbaum, A. (2011). Disruption of emotion and conflict processing in HIV infection with and without alcoholism comorbidity. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 17(3), 537–550. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1355617711000348

Seo, E., Koo, S. J., Kim, Y. J., Min, J. E., Park, H. Y., Bang, M., Lee, E., & An, S. K. (2020). Reading the mind in the eyes test: Relationship with neurocognition and facial emotion recognition in non-clinical youths. Psychiatry Investigation, 17(8), 835–839. https://doi.org/10.30773/pi.2019.0281

Slater, L. Z., Moneyham, L., Vance, D. E., Raper, J. L., Mugavero, M., & Childs, G. (2013). Support, stigma, health, co**, and quality of life in older gay men with HIV. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, 24(1), 38–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jana.2012.02.006

Spence, A. B., Liu, C., Rubin, L., Aouizerat, B., Vance, D. E., Bolivar, H., Lahiri, C. D., Adimora, A. A., Weber, K., Gustafson, D., Sosanya, O., Turner, R. S., & Kassaye, S. (2022). Class-based antiretroviral exposure and cognition among women living with HIV. AIDS Research and Human Retroviruses, 38(7), 561–570. https://doi.org/10.1089/AID.2021.0097

Stiller, J., & Dunbar, R. I. M. (2007). Perspective-taking and memory capacity predict social network size. Social Networks, 28(1), 93–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socnet.2006.04.001

Tehrani, A. M., Boroujeni, M. E., Aliaghaei, A., Feizi, M. A. H., & Safaralizadeh, R. (2019). Methamphetamine induces neurotoxicity-associated pathways and stereological changes in prefrontal cortex. Neuroscience Letters, 712, 134478. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neulet.2019.134478

Thompson, E. C., Muhammad, J., Adimora, A., Chandran, A., Cohen, M., Crockett, K. B., Friedman, M., Goparaju, L., Kempf, M.-C., Konkle-Parker, D., Kwait, J., Mimiaga, M. J., Ofotokun, I., Sharma, A., Teplin, L. A., Vance, D. E., Weiser, S., Weiss, D. J., Wilson, T., … Turan, B. (2022). Internalized HIV-related stigma and neurocognitive functioning among women living with HIV. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 36(9), 336–342. https://doi.org/10.1089/apc.2022.0041

Tipton, E. (2015). Small sample adjustments for robust variance estimation with meta-regression. Psychological Methods, 20(3), 375–393. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000011

Turan, B., Rice, W. S., Crockett, K. B., Johnson, M., Neilands, T. B., Ross, S. N., Kempf, M. C., Konkle-Parker, D., Wingood, G., Tien, P. C., Cohen, M., Wilson, T. E., Logie, C. H., Sosanya, O., Plankey, M., Golub, E., Adimora, A. A., Parish, C., Weiser, S. D., & Turan, J. M. (2019). Longitudinal association between internalized HIV stigma and antiretroviral therapy adherence for women living with HIV: The mediating role of depression. AIDS, 33(3), 571–576. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0000000000002071

Vance, D. E. (2013). The cognitive consequences of stigma, social withdrawal, and depression in adults aging with HIV. Journal Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services, 51(5), 18–20. https://doi.org/10.3928/02793695-20130315-01

Vance, D. E., Del Bene, V., Frank, J. S., Billings, R., Triebel, K., Buchholz, A., Rubin, L. H., Woods, S. P., Wei, L., & Fazeli, P. L. (2022). Cognitive intra-individual variability in HIV: An integrative review. Neuropsychology Reviews, 32(4), 855–876. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11065-021-09528-x

Vance, D. E., Fazeli, P. L., Cheatwood, J., Nicholson, C., Morrison, S., & Moneyham, L. (2019). Computerized cognitive training for the neurocognitive complications of HIV infection: A systematic review. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, 39(1), 51–72. https://doi.org/10.1097/JNC.0000000000000030

Vance, D. E., Ross, L. A., & Downs, C. A. (2008). Self-reported cognitive ability and global cognitive performance in adults with HIV. Journal of Neuroscience Nursing, 40(1), 6–13. https://doi.org/10.1097/01376517-200802000-00003

Vance, D. E., Rubin, L. H., Valcour, V., Waldrop-Valverde, D., & Maki, P. M. (2016). Aging and neurocognitive functioning in HIV-infected women: A review of the literature involving the Women’s Interagency HIV Study. Current HIV/AIDS Reports, 13(6), 399–411. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11904-016-0340-x

Velikonja, T., Fett, A. K., & Velthorst, E. (2019). Patterns of nonsocial and social cognitive functioning in adults with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry, 76(2), 135–151. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.3645

Waldrop, D., Irwin, C., Nicholson, W. C., Lee, C. A., Webel, A., Fazeli, P. L., & Vance, D. E. (2021). The intersection of cognitive ability and HIV: State of the nursing science. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, 32(3), 306–321. https://doi.org/10.1097/JNC.0000000000000232

Walzer, A. S., Van Manen, K. L., & Ryan, C. S. (2016). Other- versus self-focus and risky health behavior: The case of HIV/AIDS. Psychology, Health, and Medicine, 21(7), 902–907. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2016.1139141

Wei, J., Hou, J., Su, B., Jiang, T., Guo, C., Wang, W., Zhang, Y., Chang, B., Wu, H., & Zhang, T. (2020). The prevalence of Frascati-criteria-based HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder (HAND) in HIV-infected adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Neurology, 11, 581346. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2020.581346

Young, A. W., Perrett, D. I., Calder, A. J., Sprengelmeyer, R., & Ekman, P. (2002). Facial expressions of emotion: Stimuli and test (FEEST). Thames Valley Test Company, Bury St. Edmunds, England.

Yuvaraj, A., Mahendra, V. S., Chakrapani, V., Yunihastuti, E., Santella, A. J., Ranauta, A., & Doughty, J. (2020). HIV and stigma in the healthcare setting. Oral Diseases, 26(Suppl 1), 103–111. https://doi.org/10.1111/odi.13585

Funding

Dr. Vance is supported by an NIH/National Institute of Mental Health grant (1R01MH106366-01A1) and an NIH/National Institute on Aging grant (R21AG077957). Dr. Chapman Lambert is supported by an NIH/National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health grant (K23AT010567). Dr. Fazeli is supported by an NIH/National Institute of Mental Health grant (1R01MH131177), an NIH/National Institute on Aging grant (R21AG076377), and an Alzheimer’s Association and National Academy of Neuropsychology (ALZ-NAN-22-926241). Dr. Burel is supported by an NIH/National Heart Lung and Blood Institute grant (R01HL147603). Dr. Kempf is supported by UAB-MS CRS (Mirjam-Colette Kempf, Jodie Dionne-Odom, and Deborah Konkle-Parker), U01-HL146192. Dr. Turan is supported by an NIH/National Institute on Drug Abuse grant (R03DA052180) and an NIH/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grant (R01HL155226-01). Dr. Wise is supported by UAB HIV-Related Heart, Lung, Blood and Sleep Research K12 Career Development Program, Funded by a K12 Grant from NHLBI (K12HL143958). Dr. Rubin is supported by an NIH grant (P30MH075673). Dr. Lee is supported by NIH/National Institute of Mental Health grants (R01MH113856 & R01MH129351).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors listed met the ICMJE authorship criteria: (a) substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; (b) drafting the manuscript or revising it critically for important intellectual content; (c) final approval of the version to be published; and (d) agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. Specifically, all authors were involved with the following: (1) conceptualization, (2) writing (original draft), and (3) writing (review and editing).

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

This is a systematic review of published articles in the public domain. Ethical or human subjects approval is not required.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendix: Summary of Social Cognition in HIV Articles

Appendix: Summary of Social Cognition in HIV Articles

Baldonero et al. (2013)—Facial Emotion Recognition/Perception

In a two-group cross-sectional study, Baldonero et al. (2013) examined whether deficits in facial emotion recognition (i.e., Ekman and Friesen photographs of anger, disgust, fear, happiness, surprise, and sadness; Young et al., 2002) were observed in 49 PLHIV (Mage = 49 years) and 20 adults living without HIV (Mage = 48.5 years). Participants were administered the Facial Emotion Recognition Test (Young et al., 2002), a depression measure, and a neuropsychological test battery of 6 non-social cognitive domains. Compared to those living without HIV, PLHIV performed worse on recognizing fear, even after controlling for age and education; however, group differences in recognizing other emotion-laden facial expressions were not detected including anger, disgust, happiness, surprise, and sadness. Comparing PLHIV with (28.6%) and without (65.3%) non-social cognitive impairment, there were no group differences on fear recognition, suggesting impaired fear recognition cannot be explained by non-social cognitive impairment alone; compared separately, the PLHIV groups with or without non-social cognitive impairment still performed worse than the controls. Yet, poorer verbal recall/memory was related to poor fear recognition. Similarly, poorer overall non-social cognitive ability and more AIDS-defining conditions was related to poorer recognition of happiness. These researchers conclude that impaired fear recognition may serve as a bellwether for poor non-social cognitive functioning. A strength of this study was utilizing an HIV-negative comparison group. Although this study used validated measures of facial emotion recognition and non-social cognition, the sample size was small which limits generalizability.

Clark et al. (2010)—Facial Emotion Recognition/Perception

In a two-group cross-sectional study, Clark et al. (2010) examined facial emotion recognition ability in 50 PLHIV (Mage = 46.2 years) and 50 adults living without HIV (Mage = 44.3 years). Participants were administered a Facial Emotion Recognition Test (i.e., 84 Ekman and Friesen photographs assessing 6 emotional categories; Ekman & Friesen, 1976), a landscape categorization control task (i.e., 84 black-and-white photographs of 6 landscape categories such as tropical), the Benton Test of Facial Recognition (non-emotional face perception abilities), the Inventory of Interpersonal Problems (IIP; Horowitz et al., 1988) which has 8 subscales that assess levels of distress related to interpersonal interaction, and the WTAR (Weschler Test of Adult Reading)—a measure of intelligence. The groups did not differ on their ability to recognize novel faces or being able to categorize pictures of different landscapes; however, PLHIV performed significantly worse overall on recognizing facial emotions. Specifically, PLHIV were significantly less accurate in recognizing fear; however, no significant group differences emerged for the other facial emotions (i.e., angry, disgust, happy, sad, surprise). Since there were no other differences in the other visual recognition tests, this suggests that PLHIV experience a unique deficit in processing emotional-laden information, regarding facial expressions. Furthermore, PLHIV reported significantly more overall distress, including significantly more distress on (1) managing anger and irritability in interpersonal relationships, (2) self-sacrificing behaviors, and (3) desire to connect with others. Interestingly, in post hoc analyses, poorer facial recognition of anger was significantly associated with more distress in maintaining a sense of social connectedness; furthermore, overall intelligence accounted for 23% of the variance in anger recognition accuracy. This study is unique in attempting to measure the impact of social cognition (i.e., facial emotion recognition/perception) with social functioning (i.e., interpersonal distress). Another strength of this of this study was utilizing an HIV-negative comparison group. A limitation of this study was that it had a small sample size.

Clark et al. (2015)—Facial Emotion Recognition/Perception