Abstract

This study examines the mediation effects of forgiveness and gratitude in the association between Korean Christian young adults’ religiosity and post-traumatic growth. The participants are 296 Christian young adults in Korea. We hypothesize that the association between young Christian young adults’ religiosity and post-traumatic growth is mediated by forgiveness and gratitude. The hypothesized model is tested by structural equation modeling. Results confirm that the religiosity of Christian young adults affects post-traumatic growth through forgiveness and gratitude. Adding a direct path from religiosity to post-traumatic growth significantly improved the model fit, which suggests partial mediation of forgiveness and gratitude in the association between religiosity and post-traumatic growth.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

People in modern societies experience stress because of exposure to many unexpected events and accidents. Most people tend to overcome mild stress. However, some individuals may complain of more serious symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder after experiencing a traumatic event, such as natural disasters, traffic accidents, sexual harassment, job loss, interpersonal betrayal, and sudden death of a family member. Traumatic experiences, especially interpersonal trauma, such as a failure in an interpersonal relationship, can cause severe and intense emotional pain and seriously affect an individual’s mental health.

Experience of interpersonal trauma indicates intentional harm, such as betrayal, isolation, abuse, and abandonment by other people (Jang 2010). In studies of child abuse, domestic violence victims report that interpersonal trauma is linked to low emotional control, difficulty in interpersonal relationships, depression, eating disorders, and low self-esteem (Cloitre et al. 2005). That is, trauma resulting from interpersonal relationships has a more significant effect on the victim compared with other types of trauma (Ahn and Joo 2011). Taken together, previous literature has shown that interpersonal trauma is more severe in terms of emotional and psychological consequences than other kinds of trauma. Therefore, this study examines the impact of trauma, primarily interpersonal trauma.

Although the significant negative impact of trauma has been examined, some researchers have noted that trauma leads to improved functioning (Joseph et al. 1993; Tedeschi and Calhoun 1995). Post-traumatic growth means positive change and experiences for individuals as a result of overcoming difficulties and psychological pain caused by traumatic experiences (Tedeschi and Calhoun 1996). These changes occur in three areas, namely relationships with others, positive changes in self-perception, and positive life changes (Tedeschi and Calhoun 1996). Considering that about 70% of the general public have experienced trauma in their lifetime (The recovery village 2020), understanding the process of achieving post-traumatic growth and then experiencing functional psychological changes from traumatic experiences is necessary.

Religiosity

Religiosity can refer to the degree of internalization of individual religious beliefs (Cloitre et al. 2005; Oh 1990). An individual’s religiosity engages religious and spiritual resources to give meaning and a sense of security in chaotic situations (Spilka et al. 1985), such as during the COVID-19 pandemic (Bentzen 2020). In terms of the function of religiosity, Kotarba (1983) reported that religiosity is the primary criterion for the belief system to understand trials and losses; post-traumatic growth is associated with religious response (Lee and Lee 2011), and religiosity provides a sense of purpose and faith in dealing with trauma-related stress, which is evolutionarily adaptive (Cobb et al. 2017). Studies have indicated that religiosity has significantly predicted post-traumatic growth (Calhoun et al. 2000), but research regarding how religiosity affects post-traumatic growth has been insufficient. Therefore, in this study, we explored factors that would mediate the association between religiosity and post-traumatic growth.

Mediation Effect of Forgiveness

Forgiveness has long been associated with religious experience. Forgiveness means any effort by an injured person to release negative feelings or resentment and treat the perpetrator with compassion. Forgiveness helps to overcome negative judgment, emotion, and behavior toward persons who have been unjust and have caused a deep injury (Gassin 1995). Forgiveness is thus presented as a way of resolving conflict and injury in interpersonal relationships and is associated with physical and mental health (Park 2003). Previous studies have shown that a forgiveness program significantly decreases the level of anxiety and anger (Kwon et al. 2006) even when maternal emotional abuse was severe in childhood (Ra et al. 2010). Another aspect of forgiveness is spirituality. Religious beliefs are associated with forgiveness intention (McCullough and Worthington 2001), and forgiveness brings spiritual maturity and growth (Oh 2005). Based on the results of these prior studies, forgiveness has religious implications as a way of addressing interpersonal injury and conflict; thus, forgiveness is hypothesized to mediate religiosity and post-traumatic growth.

Mediation Effect of Gratitude

Most religions treat gratitude as an important core virtue and value (Emmons and Crumpler 2000). A grateful attitude in life is a common teaching that believers want to build and maintain within religions (Emmons and Crumpler 2000). Many previous studies have shown a significant relationship between religiosity and gratitude (Kang 2007; Kwon et al. 2006; Lyu and Cho 2009; McCullough et al. 2002). One empirical study demonstrated that people who go to church often feel grateful (Krause 2009), but the study did not distinguish internal (i.e., having internalized meaning with religious belief) vs. external religiosity (i.e., having external meaning for going to church). The present study focused on internal religiosity instead of external religiosity.

Gratitude is the adaptive behavior of recognizing and responding to the contributions of others to achieve positive outcomes (Lim 2010). Gratitude is also a factor that affects happiness, hope, optimism, and satisfaction in relationships and life (Kardas et al. 2019; Noh and Shin 2008). The higher gratitude, the less often psychological issues are experienced (Valikhani et al. 2019; Voci et al. 2019). Studies have shown that gratitude helps people to react positively to stress. However, studies on the relationship between gratitude and post-traumatic growth are rare.

People with a high propensity for gratitude can take negative events, reinterpret them (Tedeschi and Calhoun 2004) with flexible attributions (McCullough et al. 2002) and have more anger control (Jun 2016). Therefore, predicting a propensity toward gratitude may be an important factor that mediates the association between religiosity and post-traumatic growth.

Hypothesis

We hypothesize that religiosity is associated with post-traumatic growth and that this association is mediated by forgiveness and gratitude.

Method

Research Participants

Participants consisted of 320 Christian Protestant young adults living in Seoul, Gyeonggi, Daejeon, and Gangwon in South Korea. They were recruited from young adult clubs of churches. Of the 296 valid respondents (excluding data of 24 participants with incomplete responses), 132 were males (44.6%), and 164 were females (55.4%). The mean age of the participants was 27.08 years (SD = 4.81). Almost half of the participants were employed (52%), whereas the other half were students or were preparing for employment (48%). In response to the question asking how many times they go to church (Table 1), majority of the participants (77%) answered that they go to church at least once a week, 15 participants (5.1%) answered that they go to church two to three times a month, 12 participants (4.1%) answered that they go to church once a month, and 15 participants answered that they go to church three to four times a year (5.1%). Participation was anonymous, and participants were reassured of the confidentiality of their responses.

Measurements

Religiosity

This study used an intrinsic religious orientation scale developed by Allport and Ross (1967) to measure religiosity. Kim (1992) translated the scale into Korean. A total of 11 questions were given on a four-point scale (not at all = 1, very = 4) with higher scores denoting higher religiosity. In the study of Lee (2003), the reliability was 0.88 for intrinsic religiosity and 0.67 for extrinsic religiosity. In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha was 0.78 for intrinsic religiosity and 0.79 for extrinsic religiosity.

Forgiveness

To measure forgiveness, the present study used the Enright Forgiveness Inventory, which was developed by Enright (2001) and translated into Korean by Oh (2008). The inventory is composed of 24 questions, and responses are indicated using a five-point Likert scale (strongly disagree = 1, strongly agree = 5). The forgiveness scale requires individuals to recall a person who unfairly injured them psychologically or physically and to evaluate emotional, cognitive, and behavioral tendencies toward their offender. Oh (2008) reported reliability at. 95. In the present study, the overall reliability of the questions was.92, and the reliability of each subscale was. 87 for emotional forgiveness, 0.79 for cognitive forgiveness, and 0.84 for behavioral forgiveness. Cronbach’s α for the total score was 0.92.

Gratitude

The Gratitude Questionnaire-6 (GQ-6; McCullough et al. 2002) was used to measure gratitude. The GQ-6 was translated into Korean. Kwon et al. (2006) developed the Korean version of the GQ-6 (K-CQ-6). The scale consists of six questions using a seven-point Likert scale (not at all = 1; very much = 7) with higher scores indicating higher gratitude. The reliability of the K-CQ-6 (2006) scale was. 85. In the present study, the reliability was 0.85.

Post-traumatic Growth

The Post-Traumatic Growth Inventory (PTIK) developed by Tedeschi and Calhoun (1996) was used to measure post-traumatic growth. The scale consists of 21 questions that ask the extent of the positive changes identified after a traumatic experience. The scale comprises five subscales, namely new possibilities, relating to others, personal strengths, appreciation of life, and spiritual change (i.e., changes in life philosophy). Song (2007) standardized the PTIK into Korean. The scale uses a six-point Likert scale, and the higher the score, the greater the number of positive changes experienced since the trauma. In the study of Song (2007), Cronbach’s α was. 92, and the overall reliability of the measurement in this study was 0.95.

Data Collection

The survey was conducted with Protestant young adults from Seoul and surrounding cities. The researchers visited the study participants in person and administered the questionnaire. Data were also collected by young volunteers working in Protestant churches in the region. The study participants were informed about the protection of privacy and encouraged to be frank about their experiences of traumatic growth. The researcher ensured them the voluntary nature of the study. To prevent unfinished questionnaires, participants were informed in advance that the survey would take approximately 30 min.

Data Analysis

We tested the mediation model with structural equation modeling (SEM) using several recommended goodness-of-fit measures (e.g., χ2, CFI, NFI, and RMSEA) to evaluate how well the hypothesized model fits the observed data. χ2, which assesses the magnitude of the discrepancy between the fitted model and the sample, signifies a better fit if non-significant. The CFI indicates the relative fit between the hypothesized model and a baseline model that supposes no relationships among the variables. The CFI range is 0–1.0, and values closer to 1.0 indicate a better fit. NFI is derived by comparing the hypothesized model with the independence model, and 0.90 or above indicates a good model fit. The standardized RMSEA needs to be 0.05 or less in a well-fitting model.

Results

In the preliminary analyses, we deleted 24 incomplete responses. The sample (N = 296) data were univariately and multivariately normal, thereby meeting SEM assumptions. Pearson correlations (Table 2) revealed positive associations (rs = 0.15 − 0.52) for religiosity, forgiveness, gratitude, and post-traumatic growth. As indicated by the moderate correlations (below 0.85), multicollinearity is likely not a problem (Tabachnick and Fidell 2007). We used multivariate analyses of variance (MANOVAs) to examine whether any demographic item made differences in the other study variables. No significant differences were observed for sex: F(4, 291) = 0.91, p > 0.05.

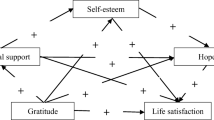

The proposed mediation model followed a two-step procedure. In the first step, confirmatory factor analysis was conducted to develop a measurement model with an acceptable fit. Once the acceptable fit was developed, the structural model was tested. The confirmatory model consisted of four latent variables and 12 observed variables. For forgiveness and post-traumatic growth, we used the subscale scores as the observed indicators of the latent variables. For religiosity and gratitude, we created item parcels using the item-to-construct balance method (Little et al. 2002). A test of the measurement model resulted in good fit indices: χ2(48) = 152.52, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.95, NFI = 0.93, RMSEA = 0.08. The hypothesized structural model was tested to determine the mediating relationships among variables in the hypothesized model, and the structural model provided a good fit to the data: χ2(50) = 171.87, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.95, NFI = 0.93, RMSEA = 0.09. To test for the best fitting model, a path between religiosity and post-traumatic growth was added (see Fig. 1), which improved the model fit significantly: χ2(49) = 157.15, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.95, NFI = 0.93, RMSEA = 0.09. The chi-square difference test confirmed that the partial mediation model was improved significantly from the original model: ∆χ2 = 1, ∆df = 14.72, p < 0.001 (Table 3), which confirmed the partial mediation model to be the best fitting model.

Discussion

Traumatic experiences can cause extreme after-effects, such as loss of control of emotion, self-injury behavior, impulsive action, helplessness, despair, withdrawal of social relationships, and interpersonal pain. However, some people experience post-traumatic growth (Tedeschi and Calhoun 1996) with greater positive changes than before. That is, those who experience painful and intense stress recognize the significance or purpose of the event and choose growth as a response. In this study, we sought to explore factors influencing post-traumatic growth. In particular, we assumed that the religiosity of Protestant young adults would influence how they experience traumatic growth. We also predicted that forgiveness and gratitude would mediate the relationship between religiosity and post-traumatic growth.

Structural equation modeling was performed to explore the hypotheses. The result of the study confirmed that forgiveness and gratitude mediate the association between religiosity and post-traumatic growth. The findings of the study signify that to help religious individuals to overcome the traumatic stress from interpersonal trauma, we need to encourage them to practice their religious beliefs by fostering forgiveness and gratitude and help them to increase their religiosity.

Forgiveness is a combination of cognition, emotion, and behavioral reactions toward offenders and is known as compassion toward them (Gassin 1995). In particular, forgiveness from a religious point of view is seen as a key concept that should be practiced by humans to improve their recovery and spiritual growth (Schultz et al. 2010). Especially, from a Christian point of view, forgiveness is an act expressed by an individual in an interpersonal relationship, which means an exemption or an unconditional rejection of God to human sin (Oh 2005).

As reviewed earlier, forgiveness is to accept and understand the person, object, and environment that caused trauma (Calhoun and Tedeschi 2006). People who experience post-traumatic growth forgive because of religiosity. Therefore, people who can increase the virtues of forgiveness through spiritual growth are likely to experience post-traumatic growth.

Those who have a high propensity for gratitude experience more positive emotion and meaning in their lives and are capable of reinterpreting an incident by finding positive aspects in traumatic situations (Calhoun and Tedeschi 2006). The results of this study could be interpreted as having a comparatively high post-traumatic growth rate for those with relatively high gratitude, which is consistent with previous research (Kim and Bae 2019). As reviewed earlier, gratitude does not involve avoiding trauma but rather implements co** strategies, such as the pursuit of social support, positive reinterpretation, proactive handling, and planning (Calhoun and Tedeschi 2006). Therefore, people who experience traumatic events should be able to increase gratitude in their lives as a way of transcending traumatic events to facilitate their personal growth.

Previous research regarding religiosity has mostly focused on older adults. Not many studies have targeted college students in religious studies, but college students’ spiritual well-being lessened trauma symptoms (Park 2017). Forgiveness has long been associated with religious experience, especially in Christianity, where forgiveness is a key virtue. In the bible, Jesus is a role model of forgiveness, and Christians believe that God has forgiven them unconditionally (Giannini 2017). Therefore, this study is significant because it examined the effects of religiosity on post-traumatic growth among Christian college students.

Limitations

First, the sample of the study was concentrated in Seoul and its suburban areas. This sample may not represent Protestant young adults living in other areas. Thus, further research with various populations would help generalize the outcomes of this study. Second, this study is intended only for young Protestants. Thus, the characteristics of other types of religious people may not be reflected in the results. Third, this study was a cross-sectional study. Different participants experienced traumatic events during different periods. Thus, our study is limited in explaining specifically when and how the post-traumatic growth process was achieved. Measuring the base levels of religiosity, forgiveness, and gratitude is also necessary to ensure accurate measurement of how individuals change after traumatic experiences. Lastly, due to research and resource limitations, this research did not further explore the percent variance with respect to mediation, nor the evidence that post-traumatic stress inventory involves philosophical change, but not religious change. These areas require further research.

References

Ahn, H. N., & Joo, H. S. (2011). The symptom structure of PTSD in simple and complex trauma type groups. Journal of Korean Psychological Association: General, 30(3), 869–887.

Allport, G. W., & Ross, J. W. (1967). Personal religious orientation and prejudice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 5, 432–443.

Bentzen, J. (2020). In crisis, we pray: Religiosity and the COVID-19 pandemic. London, Centre for Economic Policy Research. https://cepr.org/active/publications/discussion_papers/dp.php?dpno=14824.

Calhoun, L. G., Cann, A., Tedeschi, R. G., & McMillan, J. (2000). A correlational test of the relationship between post traumatic growth, religiosity, and cognitive processing. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 13(3), 521–527.

Calhoun, L. G., & Tedeschi, R. G. (2006). Handbook of posttraumatic growth. MahWah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Cloitre, M., Miranda, R., Stovall-McClough, K. C., & Han, H. (2005). Beyond PTSD: Emotion regulation and interpersonal problems as predictors of functional impairment in survivors of childhood Abuse. Behavior Therapy, 36(2), 119–124.

Cobb, M., Puchalski, C., Rumbold, B. (2017). Oxford textbook of spirituality in healthcare (Korean Translation). Seoul: The Catholic University of Korea Press and Oxford University Press.

Emmons, R. A., & Crumpler, C. A. (2000). Gratitude as a human strength: Appraising the evidence. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 19(1), 56–69.

Gassin, E. A. (1995). The will to meaning in the process of forgiveness. Journal of Psychology and Christianity, 14(1), 38–49.

Giannini, H. C. (2017). Hope as grounds for forgiveness: A Christian argument for universal, unconditional forgiveness. Journal of Religious Ethics, 45(1), 58–82.

Jang, J. Y. (2010). Traumatized self-system in adults repetitively exposed to interpersonal trauma. Doctoral dissertation, The Graduate School of Ewha Women’s University, Seoul, Korea.

Joseph, S. A., Brewing, C. R., Yule, W., & Williams, R. (1993). Causal attributions and post-traumatic stress in adolescents. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 34(2), 247–253.

Jun, W.-H. (2016). Trait anger, anger expression, positive thinking and gratitude in college students. Journal of Korean Academy of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 25(1), 28–36.

Kang, W. (2007). Religious propensity of Catholic believers and their relationship with hope, appreciation, and self-esteem. Masters dissertation. Catholic University, Bucheon.

Kardas, F., Zekeriya, C. A. M., Eskisu, M., & Gelibolu, S. (2019). Gratitude, hope, optimism and life satisfaction as predictors of psychological well-being. Eurasian Journal of Educational Research, 19(82), 81–100.

Kim, D. K. (1992). An empirical analysis and critique of Alport and Batson’s Religious Orientation Scale (pp. 211–232). Gyeonggi: Gangnam University.

Kim, E., & Bae, S. (2019). Gratitude moderates the mediating effect of deliberate rumination on the relationship between intrusive rumination and post-traumatic growth. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 2665.

Kotarba, J. A. (1983). Perceptions of death, belief systems and the process of co** with chronic pain. Social Science and Medicine, 17(10), 681–689.

Krause, N. (2009). Religious involvement, gratitude, and change in depressive symptoms over time. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 19(3), 155–172.

Kwon, S. J., Kim, K. H., & Lee, H. S. (2006). Reliability and validity of the Korean version of the audit propensity scale (K-GQ-6). Korean Journal of Clinical Psychology, 11(1), 177–190.

Lee, H. R. (2003). The effect of religious orientation and obsessive personality characteristics on thought-action fusion, Masters dissertation. Yonsei University, Seoul.

Lee, J-H., & Lee, H-K. (2011). The mediating role of meaning in life in the relationship between religious co** styles and posttraumatic growth among christians. Korean Journal of Religious Education, 36, 171–192.

Lim, K. H. (2010). Development and validation of gratitude disposition scale. Korea Journal of Counseling, 11(1), 1–17.

Little, T. D., Cunningham, W. A., Shahar, G., & Widaman, K. F. (2002). To parcel or not to parcel: Exploring the question, weighing the merits structural equation modeling. Structural Equation Modeling Multidisciplinary Journal, 9(2), 151–173. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_1

Lyu, J., & Cho, B. (2009). The mediating effect of gratitude in the relation between catholic youth’s religiosity and well-being—The implication of gratitude for youth religious education. Journal of Human Studies, 17, 69–105.

McCullough, M. E., Emmons, R. A., & Tsang, J. A. (2002). The grateful disposition: A conceptual and empirical topography. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology., 82(1), 112–127.

McCullough, M. E., & Worthington, E. L. (2001). Religion and forgiving personality. Journal of Personality, 67(7), 1141–1164.

Noh, H. S., & Shin, H. S. (2008). The mediating effect of perceived social support in the relation between gratitude and psychological well-being among adolescents. Korean Journal of Youth Studies, 15(2), 147–168.

Oh, H. (2005). Development of forgiveness counseling program for Christians. Korea Journal of Counseling, 6(1), 287–303.

Oh, K. H. (1990). Sociology of religion. Seoul: Seokwangsa.

Oh, Y. H. (2008). Preliminary study for development of Korean Forgiveness Scale. Korean Journal of Health Psychology, 13(4), 1045–1062.

Park, C. L. (2017). Spiritual well-being after trauma: Correlates with appraisals, co**, and psychological adjustment. Journal of Prevention and Intervention in the Community, 45(4), 297–307.

Park, J.-H. (2003). Explore the relationship between forgiveness and health. Korean Journal of Health Psychology, 8(2), 301–321.

PTSD Statistics [The Recovery Village]. (2020). Retrieved from https://www.therecoveryvillage.com/mental-health/ptsd/related/ptsd-statistics/.

Ra, Y. S., Hyun, M. H., Cha, S. Y., & Yun, S. Y. (2010). Relationship between a childhood emotional abuse, symptoms of complex posttraumatic stress, and forgiveness. Korean Journal of Clinical Psychology, 29(1), 21–34.

Schultz, J. M., Tallman, B. A., & Altmaier, E. M. (2010). Pathways to posttraumatic growth: The contributions of forgiveness and importance of religion and spirituality. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 2(2), 104–114.

Song, S. H. (2007). Reliability and validity of the Korean version of the posttraumatic growth inventory. Masters dissertation. Chungnam University, Daejeon.

Spilka, B., Shaver, P., & Kirkpatrick, L. (1985). A general attribution theory for the psychology of religion. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 24(1), 1–20.

Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2007). Using multivariate statistics (5th ed.). Boston: Pearson.

Tedeschi, R. G., & Calhoun, L. G. (1995). Trauma and transformation: Growing in the after math of suffering. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Tedeschi, R. G., & Calhoun, L. G. (1996). The post traumatic growth inventory: Measuring the positive legacy of trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 9(3), 455–471.

Tedeschi, R. G., & Calhoun, L. G. (2004). Post traumatic growth: Conceptual foundations and empirical evidence. Psychological Inquiry, 15(1), 1–18.

Valikhani, A., Ahmadnia, F., Karimi, A., & Mills, P. J. (2019). The relationship between dispositional gratitude and quality of life: The mediating role of perceived stress and mental health. Personality and Individual Differences, 141, 40–46.

Voci, A., Veneziani, C. A., & Fuochi, G. (2019). Relating mindfulness, heartfulness, and psychological well-being: the role of self-compassion and gratitude. Mindfulness, 10(2), 339–351.

Acknowledgement

This study was supported by the Research Fund of Hankuk University of Foreign Studies. This work was supported by the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2017S1A5A8019931). This study revised and supplemented Ji-min Kim’s Master’s thesis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Human and Animal Rights Statement

All procedures performed involving human participants in this study was in accordance with the ethical guidelines of the national research committee and the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, Jy., Kim, J. Korean Christian Young Adults’ Religiosity Affects Post-traumatic Growth: The Mediation Effects of Forgiveness and Gratitude. J Relig Health 60, 3967–3977 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-021-01213-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-021-01213-w