Abstract

Purpose

The aims of this study are to determine how continuous the care provided by physiotherapists to compensated workers with low back pain is, what factors are associated with physiotherapy continuity of care (CoC; treatment by the same provider), and what the association between physiotherapy CoC and duration of working time loss is.

Methods

Workers’ compensation claims and payments data from Victoria and South Australia were analysed. Continuity of care was measured with the usual provider continuity metric. Binary logistic regression examined factors associated with CoC. Cox regression models examined the association between working time loss and CoC.

Results

Thirty-six percent of workers experienced complete CoC, 25.8% high CoC, 26.1% moderate CoC, and 11.7% low CoC. Odds of complete CoC decreased with increased service volume. With decreasing CoC, there was significantly longer duration of compensated time loss.

Conclusion

Higher CoC with a physiotherapist is associated with shorter compensated working time loss duration for Australian workers with low back pain.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Continuity of care (CoC) is the provision of uninterrupted care by the same provider over time and is associated with improved patient outcomes [1]. Patients who experience more continuous care with the same provider report more positive patient experiences, greater patient satisfaction, higher treatment adherence, and improved health outcomes [1, 2]. Continuity of provider allows the patient–provider relationship to develop and promotes trust. It also means that “hand-overs” between healthcare providers can be avoided, limiting any information loss and ensuring treatment remains consistent.

Low back pain (LBP) is a common global health problem and is the leading cause of years lived with disability. Approximately 7.5% of the global population, or around 619 million people, suffered from LBP in 2020 [3]. LBP may result in significant economic and personal impacts, interfering with quality of life and performance at work [4]. People of working age are commonly impacted by LBP [5], with workers in many countries eligible for income support from workers’ compensation if they can prove a demonstrable link between LBP and activities of employment [6]. Workers’ compensation systems also fund healthcare. In cases of LBP, this often includes interactions with primary care providers such as general practitioners and physiotherapists.

Primary healthcare providers play critical roles in workers’ compensation systems. This includes certifying work capacity, coordinating other healthcare providers, and working with claims managers in addition to treating injured workers. Physiotherapists are common treatment providers for those with LBP. They can provide most of the recommended management options for LBP such as advice to remain active, avoid prolonged bed rest, and continue usual activities where possible for acute LBP. In addition, they can be educated about beneficial self-management options such as superficial heat [7,8,9]. For those at risk of chronic LBP (i.e. persisting beyond three months) or poor prognosis, exercise therapy with or without spinal manipulation may be recommended [7, 8].

A more continuous patient-provider relationship may lead the healthcare provider to take a more active role in coordinating healthcare, including development of a return to work plan or communication with case managers or employers [10]. Furthermore, an established relationship between a worker and their provider may negate the need for a worker to repeatedly explain to the healthcare provider their work capacity.

While an important topic, there is limited literature investigating outcomes associated with CoC in people with LBP. Van der Weide et al. (1999) found those workers with LBP who experienced higher CoC were associated with greater patient satisfaction, higher return to work rates at three months, and shorter overall time to return to work [11]. An Australian study found that workers with high CoC with a primary care physician were away from work for a shorter time, with this effect most prominent after being off work for one to two months [10]. Magel et al. (2018) undertook the only known study of physiotherapy CoC for those with LBP, and found that workers who experienced more continuous care with the same physical therapist had a lower likelihood of surgical intervention and reduced LBP-related healthcare costs [12].

It is hypothesised that physiotherapy-related CoC is also related to duration of working time loss and recovery; however, this relationship has not yet been explored. Thus, this study applies a CoC metric to workers’ compensation administrative claim data with payment-level data for all provided healthcare, allowing understanding of the relationship between CoC and recovery from LBP. In order to do so, this study has three research questions:

-

1.

How continuous is the care provided by physiotherapists to compensated workers with LBP?

-

2.

What are the demographic, occupational, and social factors associated with physiotherapy CoC among compensated workers with LBP?

-

3.

What is the association between physiotherapy CoC for compensated workers with LBP and duration of working time loss?

Methods

Setting

Each of Australia’s 6 states and 2 territories have their own workers’ compensation system. There are also three national schemes for national employers and Commonwealth government employees, the military, and seafarers. All schemes provide wage replacement payments and cover ‘reasonable and necessary’ medical expenses and services for workers with accepted claims for injuries or illnesses suffered in the course of their employment. This often includes treatment provided by physiotherapists, who can be chosen at the worker’s discretion, provided the physiotherapist is registered with the workers’ compensation scheme.

Data Source

The Monash University Multi-Jurisdictional Workers’ Compensation Database (MJD), which has been described previously, provided data for this study [13]. The MJD contains de-identified administrative workers’ compensation claims and associated service payments data for musculoskeletal conditions from five of Australia’s workers’ compensation jurisdictions, with injury dates ranging from 1 July 2010 to 30 June 2015.

Inclusion Criteria

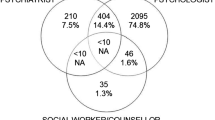

Accepted workers’ compensation claims for LBP, with a claim acceptance date between 1 July 2011 and 30 June 2015, were included. LBP claims were defined using Type of Occurrence Classification System version 3.1 nature and location of injury codes (see Supplementary Table 1) [14]. Claims from Victoria and South Australia were included as both jurisdictions contained a unique and de-identified code for each treating physiotherapist (not clinic), enabling quantification of services provided by the same physiotherapist. These two jurisdictions comprised 32% of the Australian labour force at the mid-point of this study, 2013 [15]. Claims with fewer than four physiotherapy encounters services were excluded, consistent with other CoC studies [10, 16,17,18]. Cases with missing covariate information were removed (n = 321).

Physiotherapy Encounters

Physiotherapy encounters were defined as interactions between an injured worker and a physiotherapist. Payments for report writing, review of reports or programs, supplies or equipment, or for patient non-attendance were excluded. Duplicate services were removed (e.g. no more than one encounter per worker per day).

Continuity of Care

Continuity of care with a physiotherapist was measured using the Usual Provider Continuity (UPC) index, as it is the most direct measure of the relationship between a worker and their ‘usual’ physiotherapist [19]. Calculated as the proportion of physiotherapist encounters that were with the most frequently seen service provider, the UPC has a range from \(\frac{1}{n}\) (all services with different physiotherapists) to 1 (all services with the same physiotherapist). The following categories of CoC were used, in line with previous analyses [10, 18]: Complete CoC (UPC = 1), High CoC (UPC score of 0.75–0.99), Moderate CoC (UPC score of 0.5–0.74), and Low CoC (UPC < 0.5).

Working Time Loss

Working time loss was defined as the cumulative number of calendar weeks of income support payments paid. Time loss duration was right censored at 104 weeks to remain consistent with other time loss analyses of worker’s compensation [20, 26]. Older workers were more likely to have complete CoC. It is possible they have already encountered a physiotherapist over the course of their lifetime for an unrelated condition and thus found one they trust, compared to younger workers. CoC was significantly higher in Victoria compared to South Australia.

Our study benefited from a large multi-jurisdiction sample of workers’ compensation claims. Combining claim and service-level data (that included a unique code for each physiotherapist) allowed analysis of outcomes that have not previously been measured in Australian workers’ compensation. The Usual Provider Continuity metric was considered a robust measure of CoC from previous work [10], and sensitivity analysis revealed no significant differences from the Bice-Boxerman COCI metric. However, these metrics do not consider any services paid for outside of the workers’ compensation system (e.g. by the worker themselves) but we do know they are for treatment of the same condition. We also could not account for any non-physiotherapy treatment that could support or hinder recovery. Further, it does not capture how the worker experiences CoC (e.g. relationships with different providers, transfer of information between providers). Covariates included those available in administrative data; however, there are likely more covariates that impact CoC, so residual confounding is possible. Finally, working time loss is cumulative, so for part-time workers or those who return to work partially the measure may not accurately reflect their time off work. For the purposes of Cox regression, we assumed that there was only one return to work event, which may not be valid for every worker as it fails to consider relapses.

Conclusion

Experiencing more continuous care with the same physiotherapist is associated with reduced time off work for workers with accepted workers’ compensation claims for LBP. This relationship persisted after adjusting for other covariates known to be associated with duration of time loss, such as age, sex, jurisdiction, and occupation. Findings would be of value to workers’ compensation insurers; however, future research with both existing and additional data that seeks to integrate patterns of physiotherapy use and clinical pathways, including referrals, would be valuable.

References

Jackson C, Ball L. Continuity of care: vital, but how do we measure and promote it? Aust J Gen Pract. 2018;47(10):662–664.

Fuertes JN, Mislowack A, Bennett J, Paul L, Gilbert TC, Fontan G, et al. The physician-patient working alliance. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;66(1):29–36.

Ferreira ML, de Luca K, Haile LM, Steinmetz JD, Culbreth GT, Cross M, et al. Global, regional, and national burden of low back pain, 1990–2020, its attributable risk factors, and projections to 2050: a systematic analysis of the global burden of disease study 2021. Lancet Rheumatol. 2023;5(6):e316–e329.

Ehrlich GE. Low back pain. Bull World Health Organ. 2003;81(9):671–676.

Vos T, Lim SS, Abbafati C, Abbas KM, Abbasi M, Abbasifard M, et al. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet. 2020;396(10258):1204–1222.

Oakman J, Clune S, Stuckey R. Work-related musculoskeletal disorders in Australia. Canberra: Safe Work Australia; 2019.

Corp N, Mansell G, Stynes S, Wynne-Jones G, Morsø L, Hill JC, et al. Evidence-based treatment recommendations for neck and low back pain across Europe: a systematic review of guidelines. Eur J Pain. 2021;25(2):275–295.

Oliveira CB, Maher CG, Pinto RZ, Traeger AC, Lin C-WC, Chenot J-F, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of non-specific low back pain in primary care: an updated overview. Eur Spine J. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-018-5673-2.

Australian Physiotherapy Association (APA). What is Physio? 2023

Sheehan LR, Di Donato M, Gray SE, Lane TJ, van Vreden C, Collie A. The association between continuity of care with a primary care physician and duration of work disability for low back pain: a retrospective cohort study. J Occup Environ Med/Am Coll Occup Environ Med. 2022;64(10):e606–e612.

van der Weide WE, Verbeek JH, van Dijk FJ. Relation between indicators for quality of occupational rehabilitation of employees with low back pain. Occup Environ Med. 1999;56(7):488–493.

Magel J, Kim J, Thackeray A, Hawley C, Petersen S, Fritz JM. Associations between physical therapy continuity of care and health care utilization and costs in patients with low back pain: a retrospective cohort study. Phys Ther. 2018;98(12):990–999.

Di Donato M, Sheehan L, Gray SE, Iles R, Van Vreden C, Collie A. Development and initial application of a harmonised multi-jurisdiction work injury compensation database. Digit Health. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1177/20552076231176695.

Australian Safety and Compensation Council. Type of Occurrence Classification System 3rd Edition, Revision 1. Canberra; 2008.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. Labour Force, Australia (January 2013) Canberra, Australia: Australian Bureau of Statistics; 2013 updated February 7 2013. https://www.ausstats.abs.gov.au/ausstats/meisubs.nsf/0/5F3F7E6AA336A5E2CA257B0A000ECF16/$File/62020_jan%202013.pdf.

Amjad H, Carmichael D, Austin AM, Chang CH, Bynum JP. Continuity of care and health care utilization in older adults with dementia in fee-for-service medicare. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(9):1371–1378.

Nyweide DJ, Anthony DL, Bynum JP, Strawderman RL, Weeks WB, Casalino LP, et al. Continuity of care and the risk of preventable hospitalization in older adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(20):1879–1885.

Tran B, Falster M, Jorm L. Claims-based measures of continuity of care have non-linear associations with health: data linkage study. Int J Popul Data Sci. 2018;3(1):463.

Breslau N, Reeb KG. Continuity of care in a university-based practice. J Med Educ. 1975;50(10):965–969.

Collie A, Lane TJ, Hassani-Mahmooei B, Thompson J, McLeod C. Does time off work after injury vary by jurisdiction? A comparative study of eight Australian workers’ compensation systems. BMJ Open. 2016;6(5):e010910.

Di Donato M, Iles R, Buchbinder R, **a T, Collie A. Prevalence, predictors and wage replacement duration associated with diagnostic imaging in Australian workers with accepted claims for low back pain: a retrospective cohort study. J Occup Rehabil. 2021;32(1):55–63.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. 1220.0—ANZSCO—Australian and New Zealand Standard Classification of Occupations, 2013, Version 1.2. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics; 2013.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. 1270.0.55.006—Australian Statistical Geography Standard (ASGS): Correspondences, July 2011 Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics; 2012 http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/DetailsPage/1270.0.55.006July%202011?OpenDocument.

Bice TW, Boxerman SB. A quantitative measure of continuity of care. Med Care. 1977;15(4):347–349.

Hadler NM. If you have to prove you are ill, you can’t get well the object lesson of fibromyalgia. Spine. 1996;21(20):2397–2400. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007632-199610150-00021.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Health workforce Canberra, Australia: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; 2022 updated 7 July 2022. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/workforce/health-workforce.

Acknowledgements

This study uses data supplied by WorkSafe Victoria and ReturnToWork South Australia. The results of this study represent the views of the authors, and not necessarily the views of WorkSafe Victoria or ReturnToWork South Australia.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions. SG was supported by an Australian Research Council Discovery Early Career Research Award (DE220100456). MDD was supported by the NHMRC Australia and New Zealand Low Back Pain Research Network Centre for Research Excellence (APP1171459). MDD was also supported by a project grant from the New South Wales State Insurance Regulatory Authority.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. MDD, LS, and SG prepared the data for analysis. SG and BT undertook data analysis. SG drafted the first manuscript and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gray, S.E., Tudtud, B., Sheehan, L.R. et al. The Association of Physiotherapy Continuity of Care with Duration of Time Loss Among Compensated Australian Workers with Low Back Pain. J Occup Rehabil (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-024-10209-8

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-024-10209-8