Abstract

Purpose

This paper examines the prevalence of long COVID across different demographic groups in the US and the extent to which workers with impairments associated with long COVID have engaged in pandemic-related remote work.

Methods

We use the US Household Pulse Survey to evaluate the proportion of all adults who self-reported to (1) have had long COVID, and (2) have activity limitations due to long COVID. We also use data from the US Current Population Survey to estimate linear probability regressions for the likelihood of pandemic-related remote work among workers with and without disabilities.

Results

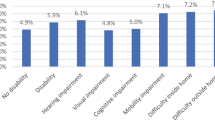

Findings indicate that women, Hispanic people, sexual and gender minorities, individuals without 4-year college degrees, and people with preexisting disabilities are more likely to have long COVID and to have activity limitations from long COVID. Remote work is a reasonable arrangement for people with such activity limitations and may be an unintentional accommodation for some people who have undisclosed disabilities. However, this study shows that people with disabilities were less likely than people without disabilities to perform pandemic-related remote work.

Conclusion

The data suggest this disparity persists because people with disabilities are clustered in jobs that are not amenable to remote work. Employers need to consider other accommodations, especially shorter workdays and flexible scheduling, to hire and retain employees who are struggling with the impacts of long COVID.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Notes

According to this DHHS guidance, a person with a disability is defined as someone having a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits at least one of their major life activities; and a reasonable accommodation is an adjustment of an organization’s policies, practices, or workspace that allows people with disabilities to have equal access to opportunities and employment.

The data and questionnaires are publicly available at: https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/household-pulse-survey/datasets.html.

Computed from response rates published at https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/covid19/pulse/long-covid.htm.

People who are SGM self-identified their sexual orientation as gay, bisexual, “something else,” or gender identification as transgender in the HPS survey [11]. The combined SGM category is heterogeneous; we do not mean to imply that gay, bisexual, and transgender people have comparable experiences in daily life or in the labor market.

The disability data in the HPS may include people with disabilities from long COVID, but the majority of disabilities were likely preexisting disabilities, as indicated by the trend analysis in section “Prevalence and Repercussions of Long COVID.”

Across the ten rounds of HPS data we analyzed, 6.5% of women reported severe difficulty remembering or concentrating compared to 4.5% of men.

The 23,000 students were in 9th grade in 2009 and were surveyed in 2016; the data aggregate student self-reports, school reports on students with Individualized Education Programs, and parent reports of diagnoses by health or education professional [25].

Calculation based on data in Newman et al. [25].

References

Department of Health and Human Services. National research action plan on long COVID. Report. 2022. www.covid.gov/assets/files/National-Research-Action-Plan-on-Long-COVID-08012022.pdf.

Devoto SA. Long COVID and chronic pain: overlap** racial inequalities. Disabil Soc. 2023;38(3):524–529.

Department of Health & Human Services, and Department of Justice. Guidance on “long COVID” as a disability under the ADA, section 504, and section 1557. Press release. 2021. https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/doj-and-hhs-issue-guidance-long-covid-and-disability-rights-under-ada-section-504-and-section.

Abbasi J. The US now has a research plan for long COVID—is it enough? JAMA. 2022;328(9):812–814.

Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health. Health+ long COVID human-centered design report. 2022. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/healthplus-long-covid-report.pdf.

Smith MP. Estimating total morbidity burden of COVID-19: relative importance of death and disability. J Clin Epidemiol. 2022;142:54–59.

Cutler D. The economic cost of long COVID: an update. Harvard University Working Paper. 2022. https://scholar.harvard.edu/files/cutler/files/long_covid_update_7-22.pdf.

Davis HE, Assaf GS, McCorkell L, Wei H, Low RJ, Re’em Y, Redfield S, Austin JP, Akrami A. Characterizing long COVID in an international cohort: 7 months of symptoms and their impact. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;38:101019.

McLaren J. Racial disparity in COVID-19 deaths: seeking economic roots with census data. BE J Econ Anal Policy. 2021;21(3):897–919.

Grobelny J. Factors driving the workplace well-being of individuals from co-located, hybrid, and virtual teams: the role of team type as an environmental factor in the job demand-resources model. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(4):3685.

Household Pulse Survey. 2021 Household Pulse Survey user notes. Survey documentation. 2021. https://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/demo/technical-documentation/hhp/Phase3-2_2021_Household_Pulse_Survey_User_Notes_092221.pdf.

Sudre CH, Murray B, Varsavsky T, Graham MS, Penfold RS, Bowyer RC, Pujol JC, Klaser K, Antonelli M, Canas LS, Molteni E. Attributes and predictors of long COVID. Nat Med. 2021;27(4):626–631.

Perlis RH, Santillana M, Ognyanova K, Safarpour A, Trujillo KL, Simonson MD, Green J, Quintana A, Druckman J, Baum MA, Lazer D. Prevalence and correlates of long COVID symptoms among US adults. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(10):e2238804.

Prince SA, Adamo KB, Hamel ME, Hardt J, Gorber SC, Tremblay M. A comparison of direct versus self-report measures for assessing physical activity in adults: a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2008;5(1):1–24.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. Women in the labor force: a databook. 2023. https://www.bls.gov/opub/reports/womens-databook/2022/home.htm.

Dorfman D, Berger Z. Approving workplace accommodations for patients with long COVID—advice for clinicians. N Engl J Med. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp2302676.

Reynolds BW. The mental health benefits of remote and flexible work. In: Mental Health America. 2020. https://www.mhanational.org/blog/mental-health-benefits-remote-and-flexible-work.

Sheiner L, Salwati N. How much is long COVID reducing labor force participation? Not much (so far). Hutchins Center Working Paper No. 80. 2022. https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/WP80-Sheiner-Salwati_10.27.pdf.

Fancello V, Fancello G, Hatzopoulos S, Bianchini C, Stomeo F, Pelucchi S, Ciorba A. Sensorineural hearing loss post-COVID-19 infection: an update. Audiol Res. 2022;12(3):307–315.

Ameri M, Kruse D, Park SR, Rodgers Y, Schur L. Telework during the pandemic: patterns, challenges, and opportunities for people with disabilities. Disabil Health J. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2022.101406.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. Persons with a disability: labor force characteristics—2022. USDL-23–0351. 2023. www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/disabl.pdf.

Schur LA, Ameri M, Kruse D. Telework after COVID: a “silver lining” for workers with disabilities? J Occup Rehabil. 2020;30:521–536.

Telwatte A, Anglim J, Wynton SK, Moulding R. Workplace accommodations for employees with disabilities: a multilevel model of employer decision-making. Rehabil Psychol. 2017;62(1):7.

Lindsay S, Cagliostro E, Carafa G. A systematic review of workplace disclosure and accommodation requests among youth and young adults with disabilities. Disabil Rehabil. 2018;40(25):2971–2986.

Newman L, Wagner M, Knokey AM, Marder C, Nagle K, Shaver D, Wei X. The post-high school outcomes of young adults with disabilities up to 8 years after high school: a report from the National Longitudinal Transition Study-2 (NLTS2). NCSER 2011-3005. National Center for Special Education Research. 2011.

Schur L, Rodgers YV, Kruse DL. COVID-19 and employment losses for workers with disabilities: an intersectional approach. In: Beatty J, Hennekam S, Kulkarni M, editors. De Gruyter handbook of disability and management. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter GmbH; 2023. p. 83–104.

Sherbin L, Kennedy JT, Jain-Link P, Ihezie K. Disabilities and inclusion. Coqual report. 2017. https://coqual.org/reports/disabilities-and-inclusion/.

Jain-Link P, Taylor Kennedy JT. Why people hide their disabilities at work. Harvard Business Review. June 3, 2019. https://hbr.org/2019/06/why-people-hide-their-disabilities-at-work.

Jolivet DN. 5 things employers need to know about accommodating long COVID. @Work. Disability Management Employers Coalition. September 18, 2022. http://dmec.org/2022/09/18/5-things-employers-need-to-know-about-accommodating-long-covid/.

Lunt J, Hemming S, Elander J, Baraniak A, Burton K, Ellington D. Experiences of workers with post-COVID-19 symptoms can signpost suitable workplace accommodations. Int J Workplace Health Manag. 2022;15(3):359–374.

Lund EM, Ayers KB. Ever-changing but always constant: “Waves” of disability discrimination during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. Disabil Health J. 2022;15(4):101374.

Kaye HS, Jans LH, Jones EC. Why don’t employers hire and retain workers with disabilities? J Occup Rehabil. 2011;21:526–536.

Schur L, Nishii L, Adya M, Kruse D, Bruyère SM, Blanck P. Accommodating employees with and without disabilities. Hum Resour Manag. 2014;53(4):593–621.

Waddell G, Burton AK, Kendall NA. Vocational rehabilitation–what works, for whom, and when? (Report for the Vocational Rehabilitation Task Group). TSO; 2008.

Cohen J, Rodgers Y. The feminist political economy of COVID-19: capitalism, women, and work. Glob Public Health. 2021;16(8–9):1381–1395.

Blau FD, Koebe J, Meyerhofer PA. Who are the essential and frontline workers? Bus Econ. 2021;56:168–178.

Small SF, Rodgers Y, Perry T. Immigrant women and the COVID-19 pandemic: an intersectional analysis of frontline occupational crowding in the United States. Forum Soc Econ. 2023;19:1–26.

Harpur P, Blanck P. Gig workers with disabilities: opportunities, challenges, and regulatory response. J Occup Rehabil. 2020;30:511–520.

Funding

Author YR has received funding support from the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research (NIDILRR) for the Rehabilitation Research & Training Center (RRTC) on Employment Policy: Center for Disability-Inclusive Employment Policy Research Grant [Grant Number #90RTEM0006-01–00] and by the NIDILRR RRTC on Employer Practices Leading to Successful Employment Outcomes Among People with Disabilities Research Grant [Grant Number #90RTEM0008-01-00].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JC and YMR wrote the main manuscript text. JC conducted the HPS analysis, and YMR conducted the CPS analysis. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethical Approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Institutional Review Board of Rutgers University, October 20, 2022, Study ID Pro2021002068.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Cohen, J., Rodgers, Y.v. Long COVID Prevalence, Disability, and Accommodations: Analysis Across Demographic Groups. J Occup Rehabil 34, 335–349 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-024-10173-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-024-10173-3