Abstract

The significance of environmental protection activities is well known, but little literature has focused on the well-being effects of environmental protection behavior among farmer groups. This study provides new literature support for farmers and rural development issues. Using data from the 2013 China Integrated Social Survey, a systematic and robust examination of the happiness effects of environmental protection behavior among Chinese farmers and their transmission mechanisms was conducted with the help of multiple regression techniques and mediated impact analysis. The study found that Chinese farmers' environmental protection behavior can directly trigger the experience of well-being and also indirectly enhance subjective well-being by improving the quality of life in other areas, thanks to their characteristics in avoiding environmental risks and enhancing social interactions. Increased education may contribute to farmers being more motivated by benefits such as material rewards, experience, and skills, and thus experiencing less well-being from environmental protection behavior. The fact that farmers of all household incomes experience equal well-being from environmental protection behavior is consistent with the view of non-differential well-being experiences in the volunteering literature. The research in this paper adds new evidence to the existing literature and provides an essential reference for policymakers and participants in rural development in China. In addition, studying individual issues in environmental governance in rural China provides a Chinese case study and practical lessons for farmer development in other countries worldwide.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

With the development of science and technology and economic globalization, the world economy is facing the dilemma of ecological environment destruction while develo**. In modern times, the extreme expansion of anthropocentric ideology and the excessive pursuit of material wealth by human beings have led to the disregard for the critical value of the ecological environment. The predatory exploitation and unreasonable utilization by human beings have led to various ecological and environmental elements and their services becoming scarce resources. The era of ecological constraints has arrived, and the basis for human survival and sustainable development is being threatened (Costanza, 1989). Develo** countries are in the primary stage of economic growth. The level of technology is low, and the environment is under the double pressure of development and population, coupled with the transfer of some heavily polluting industries from developed to develo** countries, making the environmental pressure on develo** countries more severe. China is a typical representative of develo** countries. Over the past 40 years of reform and opening up, China's economy has made world-renowned achievements and contributed significantly to world economic growth. However, China's rapid economic growth has come at the cost of environmental degradation and excessive consumption of resources. China's development has not departed from the empirical path developed countries take, which is a microcosm of the world's economic development, and most other develo** countries are no exception. Diseases caused by environmental pollution make people's health costs much higher, which plays a role in offsetting the welfare improvement brought by economic growth. There may even be a negative net welfare situation (Yang et al., 2013). The happiness of residents decreases due to environmental pollution. There is a growing awareness of the important role that the natural environment plays in well-being, and the impact of environmental quality on well-being has been studied (Krekel et al., 2020).

Develo** countries have large agricultural populations, and China alone has a rural population of 509.8 million, accounting for 36.11% of China's total population.Footnote 1 Farmers are important social subjects, and the country's happiness cannot be separated from the happiness of farmers. Happy countries prosper in terms of GDP, productivity, low corruption and social support (Kaklauskas et al., 2020), and the country's happiness is predicated on the people's happiness. Therefore, it becomes crucial to ensure the country's happiness and prosperity and the farmers' happiness. Happiness is an important comprehensive indicator of individual self-assessment of well-being, and worldwide, happiness is gradually becoming a new pursuit of governments and societies "beyond GDP". Welfare policies that focus on well-being rather than income indicators contribute to the goal of environmental and social sustainability (Gowdy, 2005) and are also a better measure of social progress (Breslow et al., 2016). The role of farmers, who have fewer alternative pathways to happiness due to lower incomes, may be more pronounced due to the decline in happiness caused by environmental pollution. Environmental pollution will not disappear because of economic growth (Lorente et al., 2016), and effective measures must be taken to protect the environment. Most of the existing literature focuses on the effects of environmental governance and the influencing factors of environmental protection in China. In contrast, little literature focuses on the well-being effects of farmers' autonomous participation in environmental protection. Therefore, it is of great theoretical value and practical significance to study the influence of farmers' environmental protection behavior on their well-being and its mechanism of action. This study meets the needs of the times and provides theoretical support and empirical evidence for countries worldwide, especially develo** countries, to promote farmers' well-being and build happy societies and beautiful countries.

Based on the above analysis, this study attempts to make the following contributions: first, based on the importance and specificity of the farmers' group, the influence of farmers' environmental protection behavior on their subjective well-being is discussed, adding new evidence to the discussion of the relationship between environmental protection and public well-being, and ensuring a complete lineage of evidence for research on the topic of environmental protection and general well-being. Secondly, multiple methods are estimated to provide more comprehensive empirical evidence. The results are more robust and reliable, enhancing the credibility and validity of the extension of research findings. Thirdly, examining and analyzing the moderating and mediating mechanisms of farmers' environmental protection behavior on their subjective well-being provides additional evidence, enriching the theoretical logic of the multiple effects of environmental protection behavior on well-being and extending the existing literature. Fourthly, it provides empirical support for countries worldwide to promote farmers' active participation in environmental protection to enhance their subjective well-being.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows: the second part is to present the analytical framework and research hypotheses of this paper based on the theoretical analysis.; the third part is the research design, which focuses on the detailed introduction and description of the data, variables, and methods used in this paper; the fourth part is the analysis of the empirical results and robustness tests; the fifth part is the extended analysis, which further examines the mechanisms of farmers' environmental protection behavior; and finally, the full text contains conclusions and suggestions.

1.1 The Connotation and Influencing Factors of Subjective Well-Being

The ancient Greek philosophers Epicurus and Herakleitus were the first to study "happiness"(Zhou, 1987), and scholars have used their ideas of "happiness" as the basis for a new interpretation of happiness from the perspectives of sociology, economics, and ethics. In general, happiness has been divided into subjective happiness, which focuses on subjective experience, and objective happiness, which emphasizes the objective reality of happiness. Compared with objective happiness, subjective happiness is more inclusive. In Europe and the United States, subjective well-being has been studied in psychology and sociology since the 1950s (Galbraith, 1998). Keyes (2006) classified subjective well-being into three dimensions: life satisfaction, positive affect, and negative affect. Subjective well-being reflects people's material living standards and psychological satisfaction and is a comprehensive measure of people's satisfaction and well-being in life (Frey et al., 2002). Cui (2015) believes that subjective well-being is a cognitive and affective overall evaluation of people's satisfaction with their quality of life and is an important comprehensive indicator of people's quality of life. Katsumi (2021) argued that subjective well-being is a complete index of people's multidimensional evaluation of their daily emotional experiences and life satisfaction. In general, subjective well-being consists of two main dimensions: the life situation cognitive dimension and the affective situation assessment dimension, which is people's perception of their life situation and their assessment of their affective state. This paper focuses on the life perception dimension of subjective well-being.

Academics have widely recognized the subjective nature of well-being, and this subjective feeling is also considered a concrete manifestation of objective phenomena map**. Inspired by the "Easterlin paradox", scholars have done a lot of research on the factors influencing happiness and have achieved rich research results based explicitly on the relationship between income and subjective well-being. They have continuously incorporated personal and family characteristics, macro, public service, and social capital into the research framework. (1) Individual and family characteristics factors. Oswald (1997) argued that the relationship between age and subjective well-being is not a simple linear relationship but a U-shaped relationship. In addition to the effect of age on happiness, Yuan (2017) argues that marriage can significantly and positively affect happiness, women have higher marital happiness than men, and children have a negative role in marital happiness; Qiu (2021) argues that young people's subjective well-being increases with their level of education. (2) Macro factors. Knight (2010) argues that the urban–rural split makes happiness heterogeneous. Wilson (2020), and Rizkallah (2021), study the influencing factors of happiness in terms of economic growth and fiscal policy, respectively. (3) Public services. Leite (2020) argues that public health policies can impact happiness. Zhang (2020) found that rural public service provision can positively affect farmers' subjective well-being under the premise of meeting their needs. Some scholars still believe that the impact of public service expenditures on residents' subjective well-being does not always show a significant positive effect(Wang et al., 2021). (4) Social capital. Kislev (2020) found that singles have higher social capital and positively impact happiness. Arampatzi (2018) argues that social capital can moderate social networking site use on well-being. However, Ram (2009) concluded that social capital has a minor significant role in generating happiness.

1.2 The Connotation and Influencing Factors of Environmental Protection Behavior

There has been no consensus in academia on the definition of environmental protection behavior, and early studies equated environmental protection behavior with attitudes (Barkan, 2004). Harris (2008) found that Chinese people are mentally willing to engage in environmental protection but are less likely to act on it. Zhang (2016) considers environmental protection or environmentally friendly behavior as that protective behavior that has a favorable and positive impact on the environment. Tang (2017) considers environmental behavior as that behavior in which individual or group activities can positively or negatively affect the environment, while conservation behavior reflects only positive effects. Although different scholars define the concept of environmental protection behavior differently, they all reveal the unified connotation of environmental protection behavior, which are pro-social or pro-environmental behavior in the environmental field, in which the voluntary or involuntary contribution of individuals or groups is exchanged for the long-term benefits of the majority of people, to achieve sustainable development.

Research on the influencing factors of environmental protection behavior has been a hot issue. Scholars have explored and studied it from multiple perspectives, scopes, and methods, basically based on Sia's (1986) environmental literacy model, Ajzen's (1991) theory of planned behavior, and Stern's (2005) value-belief-norm theory for related research. Many factors influence environmental protection behavior, which can be broadly classified into internal and external factors. Internal factors include demographic characteristics, values, and environmental perceptions. Many scholars believe that demographic characteristics can explain only a small part of residents' environmental protection behavior. There may be opposite results on the influence of demographic characteristics on environmental protection behavior under different scenarios. Kim (2020) argues that altruistic values and attitudes can positively impact environmental protection behavior. Bradley (2020) argued that there are differences in the effects of environmental risk perception on environmental protection behavior within different countries. External environmental factors mainly include economic development, urbanization, environmental pollution, etc. Most scholars believe economic development can increase public awareness and environmental protection behavior (Diekmann et al., 1999). However, some scholars still dispute this, arguing that environmental protection behavior is common worldwide. The level of economic development does not affect it (Dunlap et al., 1995), and even the public in rich countries is more reluctant to engage in environmental protection activities (Dunlap et al., 2008). Zhan (2021) argues that the level of urbanization can positively influence individual and public environmental protection behavior. There are also two views on the effect of environmental pollution on environmental protection behavior, i.e., environmental pollution drives environmental protection behavior to occur (Marquart, 2007), and environmental quality does not affect environmental protection behavior (Franzen et al., 2010).

1.3 The Impact of Environmental Quality on the Population's Well-Being

Most scholars believe that a good environment can enhance residents' happiness, while a bad environment can make people feel miserable and desperate, reducing their happiness. The impact of environmental quality on happiness can be broadly divided into two aspects: natural environmental pollution and social environmental quality. Natural environmental pollution is usually subdivided into specific environmental pollution that impacts well-being, such as air pollution, water pollution, noise pollution, and natural disasters (Li et al., 2020; Weinhold, 2013; Rehdanz et al., 2015). Atmospheric pollution, noise pollution, and natural disasters significantly negatively affect well-being. In contrast, water pollution does not have as strong an effect on well-being as the three factors mentioned above. Scholars have studied the impact of the social environment's quality on residents' well-being through the residential environment, the work environment, and a particular social event. Ambrey (2011) argues that strengthening community environmental management and improving amenity environmental management positively affects residents' happiness. Frey (2009) argues that social unrest caused by social events, including civil war, corruption, and terrorism, can significantly reduce residents' happiness.

The above review reveals extensive literature on the connotation of happiness, the connotation of environmental protection behavior, and the influencing factors, and many research results have been obtained. Most of the literature focuses on negative environmental behavior, such as environmental pollution, resource waste, and ecological imbalance, which have a negative impact on people's well-being. However, relatively little research has been conducted on how positive environmental behavior, i.e., environmental protection behavior, can affect well-being. At the same time, since the enhancement of farmers' well-being in China is getting more and more widespread attention, this study focuses on the farmers' group. It explicitly analyzes the effects of their environmental protection behavior on well-being to enrich the literature related to residents' well-being, especially farmers' well-being and provides theoretical and practical references for formulating relevant policies to enhance people's well-being.

2 Theoretical Analysis and Research Hypothesis

People's satisfaction with their desires is the traditional economic view of happiness, using the utility to reflect happiness and incorporating wealth and income into welfare analysis. Samuelson (1948) established the happiness equation, where happiness equals the ratio of utility to desire, and utility and desire jointly determine happiness. Happiness economics is based on traditional economics, sociology, and psychology. It uses the expressed preference method to measure happiness, a combination of others' evaluations and self-reports (Larsen et al., 1985). Hence, to more accurately measure the change in happiness caused by the reality of people's performance after making choices. In contemporary happiness research, happiness economics usually uses subjective evaluations to reveal happiness levels and uses happiness functions instead of utility functions to measure subjective happiness. Happiness economics measures happiness on the logical premise that only one's true feelings expressed through personal experience are the closest to one's actual level of happiness. Therefore, happiness economics usually adopts sociological and psychological research methods such as questionnaires, scales, and interviews based on economic theories, and conducts happiness surveys on people of different cultures, countries, incomes, classes, and occupations, and establishes happiness functions to discriminate happiness levels and influencing factors instead of the traditional economic utility functions. According to the above analysis, the happiness function, including income or wealth, and other factors such as population, environment, and desires, is constructed as follows.

In Eq. (1), WB is subjective well-being, C denotes consumption, and S denotes wealth or income. Needs play an important role in subjective well-being, and people's needs usually consist of material needs and non-material needs. Material needs are more basic, and wealth and income can be used for people's consumption to maintain the basic survival of individuals, which in turn can lead to increased satisfaction. According to Maslow's (1943) hierarchy of needs theory, respect and self-actualization belong to the higher level of non-material needs, represented here by UD. X denotes population, resources, environment, economy, policies, etc. Various objective conditions are the basis for demand generation, and changes in objective conditions will cause demand to change continuously.

Environmental protection behavior is pro-environmental behavior, a proactive series of measures to solve existing environmental problems. Environmental protection behavior positively reduces pollutant emissions and energy consumption, improving environmental conditions. The effective implementation of environmental protection behavior can directly impact the subjective well-being of rural residents. On the one hand, as farmers' awareness of environmental protection increases, environmental protection behavior become more positive, reducing their concern about environmental pollution and increasing their confidence in improving environmental quality. On the other hand, environmental protection behavior can reduce environmental pollution, avoid wasting resources, and thus improve the environmental situation and enhance the momentum of sustainable development, farmers' living environment and quality can also be improved, and farmers' subjective well-being will increase. In addition, the perceived well-being of people in a self-perceived beautiful environment is more pronounced (Mackerron et al., 2013). Also, because the perceived level of farmers' subjective well-being is not entirely consistent, there may be some differences in the well-being effects of adopting environmental protection behavior at different levels of subjective well-being. Based on this, the following hypotheses are proposed in this study.

Hypothesis 1

There is a "happiness effect" of farmers' environmental protection behavior, i.e., farmers can directly experience happiness from environmental protection behavior.

Hypothesis 2

There is a significant difference in the marginal probability effect of farmers' environmental protection behavior at different levels of subjective well-being.

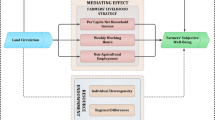

Environmental protection behavior can have both a direct effect on farmers' subjective well-being and an indirect effect on farmers' subjective well-being by influencing moderating variables including farmers' perceptions of local government's environmental governance, household income, and education, and mediating variables including farmers' self-rated health status, social interaction, and social trust. The stronger the objective environmental regulation exists, the better the effect of environmental management will be, and the better the farmers' subjective perception of environmental conditions. This improvement in the living environment will improve farmers' quality of life and satisfy farmers' pursuit of a better life. Farmers will be more willing to carry out environmental protection, and their happiness will significantly increase. At present, the income level of Chinese farmers has not yet reached the threshold of "Easterlin's paradox"(Easterlin, 1974), and the increase in the income level of farmers' families will improve their happiness. In addition, after the basic material needs of farmers are met, the motivation of spiritual needs will be further stimulated, and environmental protection behavior will be more proactive. The lower-income class attribute of Chinese farmers makes income improvement still an important source of subjective well-being, and the higher the education level, the stronger the desire for material things and skills, and the relatively less investment in environmental protection behavior, coupled with the negative effect of education level on subjective well-being (Knight et al., 2010), this " masking effect" on subjective well-being makes the positive effect of environmental behavior on subjective well-being weaker. Farmers' pro-environmental behavior can affect their subjective well-being by improving environmental quality, reducing the chances of illness, and improving their health. Social capital factors such as social interaction and social trust have a transmission role in farmers' environmental protection behavior affecting their subjective well-being.Farmers' environmental protection behavior can increase the frequency of interaction and exchange of experiences among people, enhancing their subjective well-being. At the same time, the interaction between farmers' environmental protection behavior can enhance their trust, forming a "clustering effect" to a certain extent and making farmers' subjective well-being significantly higher. Based on the above analysis, the following hypotheses are proposed.

Hypothesis 3

The perception of environmental governance, household income, and education have moderating effects on farmers' happiness experience of environmental protection behavior.

Hypothesis 4

Self-rated health, social interaction, and social trust have a facilitative effect on farmers' subjective well-being, as well as a conductive impact on the well-being effect of environmental protection behavior.

3 Data, Variables, and Methods

3.1 Data Sources

This paper uses data from the Chinese General Social Survey (CGSS) 2013 to examine the effect of farmers' environmental protection behavior on their subjective well-being. CGSS is a comprehensive and continuous academic survey project jointly executed by the Renmin University of China and academic institutions across China. The CGSS survey was conducted in 32 provinces (municipalities and districts) across China with random sampling and a stratified, multi-stage, whole-group sampling design. The CGSS project's survey data for the 2013 round only covers multiple dimensions of environmental protection indicators. The discussion using data from that year can more fully reflect the well-being effects of farmers' environmental behavior. There are 11,438 available samples in the CGSS data in 2013, and this paper extracts 4312 valid samples based on the questionnaire "What is your current hukou registration status?" The sample of "agricultural hukou" individuals was extracted. Finally, 4312 valid samples were obtained, covering 83 prefectural administrative units in China, representing the whole country.

In addition, this paper also collects the latest publicly available data from various surveys in China. Still, unfortunately, the content of the investigation regarding environmental protection behavior could not be found. Only the China Comprehensive Social Conditions Survey (CSS), sponsored by the Institute of Sociology, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS), the most recent CSS2019 data contains environmental behavior content. Still, the survey does not have a detailed environmental behavior scale but a multiple choice restricted question in the volunteering module. The low response rate, which greatly reduces the statistical efficacy, is the main reason for choosing CGSS2013 data for this paper. Of course, the estimation results of CSS2019 are also given later as a robustness test to verify the temporal continuity of the happiness effect of environmental protection behavior and the reasonableness of the selected data.

3.2 Variable Descriptions

3.2.1 Subjective Well-Being

The explanatory variable in this paper is subjective well-being. As defined in the previous paper and regarding Huerta (2021), Hu (2022), and other scholars, we mainly measure subjective well-being using the perception of life dimension. Since there is no more detailed scale in the questionnaire, this paper primarily uses the question "In general, do you think you are happy in your life" to measure, which is divided into five levels: very unhappiness, relatively unhappiness, not sure, somewhat happiness and very happiness, and scored by the numbers 1 to 5, with the degree of subjective well-being increasing in order. This indicator was used because this measure reflects respondents' comprehensive evaluation of the multidimensional quality of life and has better statistical reliability, validity, and psychometric adequacy.

3.2.2 Environmental Protection Behavior

The core explanatory variable in this paper is environmental protection behavior, which reflects altruistic behavior exhibited by an individual or group activity covering all activities to protect the environment or prevent environmental degradation (Stern, 2002). The CGSS questionnaire examines residents' environmental protection behavior through 10 questions, namely, "Separate and put out the garbage", "Discuss environmental issues with relatives and friends", "Bring shop** bags", "reuse plastic bags", "donate money for environmental protection", "actively pay attention to environmental issues and environmental information ", and "actively participate in the government's ", "actively participate in environmental education activities organized by the government and organizations", "actively participate in environmental protection activities organized by private environmental groups", "maintain woods or green areas at their own expense ", and "actively participate in complaints and appeals demanding solutions to environmental problems". In this paper, we used the numbers 0, 1, and 2 to reassign each category of environmental protection behavior, and Cronbach's coefficient for these ten questions was 0.703, which has a high internal consistency. Therefore, we construct a composite indicator of environmental protection behavior by accumulating scores and further dividing it by 4 to reduce it to a continuous variable taking values in the 0–5 range, with higher scores indicating better performance in environmental protection behavior.

3.2.3 Mediating Variables

Altruistic environmental behaviors may indirectly enhance well-being through improving health, social interaction, and social trust, so health, social interaction, and social trust are mediating variables for the well-being effects of farmers' environmental protection behaviors. Respondents' self-rated health measured health status. Social interaction was measured by the question, "Have you engaged in social activities regularly in the past year", and social trust was measured by the question "Do you agree that most people in this society can be trusted? All three mediating variables were measured on a scale of 1 to 5, with higher scores representing better health, more frequent social interaction, and more social trust.

3.2.4 Moderating Variables and Residual Covariates

We selected respondents' household income, education level, and evaluation of the local government's environmental governance as moderating variables. The question of environmental governance is "How do you think the regional government has been doing in environmental protection in the past five years", with increasing scores from 1 to 5 indicating that environmental governance is improving. Household income is measured as the logarithm of total household income in the previous year, and educational attainment is combined and treated on an increasing scale of 1 to 6. To reduce the effects of omitted variables, age, gender, marriage, job, and city-fixed effects were further introduced as control variables, drawing on the classic literature on the factors influencing Subjective well-being (Knight et al., 2009). Considering that middle-aged people are more stressed and adolescents and older people are less stressed, we also introduced an age-squared term to examine the nonlinear relationship between age and subjective well-being (Oswald, 1997). The symbols, names, and specific assignments of the relevant variables are shown in Table 1.

3.3 Model Setting

3.3.1 Baseline Regression Model

We start with the estimation of direct effects, and in this paper we set the benchmark model as follows.

where, \({\text{happiness}}_{{\text{i}}}\) is the dependent variable for subjective well-being; \({\text{enpb}}_{{\text{i}}}\) is the farmer's environmental protection behavior variable that is the focus of this paper, which \({\text{X}}_{{\text{i}}}\) is a series of control variables such as self-rated health, social interaction, social trust, environmental governance, household income, education, age, age squared, gender, marriage, work; \({\upvarepsilon }_{{\text{i}}}\) is the random error term. \({\upbeta }_{0}\) is the intercept term, \({\upbeta }_{1}\) is the marginal coefficient of farmers' environmental protection behavior. Since the dependent variable is ordered categorical variables, the ordered Probit model is used for estimation. The estimated results of OLS and ordered Logit models are included in the baseline regression analysis section for comparison.

3.3.2 Moderating Effects Model

We added the interaction terms of household income, education level, perceived environmental governance, and environmental protection behavior to Eq. (2). The specific model was set as follows.

where, \({\text{R}}_{{\text{i}}}\) refers to the moderating variables related to household income, educational attainment, and perceived environmental governance.\({\text{enpb}}_{{\text{i}}} \times {\text{R}}_{{\text{i}}}\) refers to the interaction terms of each of the three with environmental protection behavior, and the direction and strength of the moderating effect of the corresponding variables on the happiness effect of environmental protection behavior can be further identified by the estimation test of the coefficient \({\upbeta }_{3}\). \({\text{X}}_{{\text{i}}}\) is the remaining set of control variables, which \({\text{e}}_{{\text{i}}}\) are the random residual terms of the model.

3.3.3 Mediating Effects Model

Referring to Baron and Kenny's (1986)mediation effect test steps, this paper identifies the following three equations by estimating them with the following model settings.

where, \({\text{M}}_{{\text{i}}}\) refers to the mediating variables for self-rated health, social interaction, and social trust, \({\text{X}}_{{\text{i}}}\) is the residual covariate, and \({\text{u}}_{{1{\text{i}}}}\), \({\text{u}}_{{2{\text{i}}}}\), and \({\text{u}}_{{3{\text{i}}}}\) are the random residual terms.The coefficient \({\upalpha }_{1}\) represents the total effect of farmers' environmental protection behavior on subjective well-being; the coefficient \({\updelta }_{1}\) represents the effect of environmental protection behavior on each mediating variable\({\mathrm{M}}_{\mathrm{i}}\); the coefficient \({\upbeta }_{2}\) represents the effect of each mediating variable on subjective well-being under the condition of controlling for environmental protection behavior and the coefficient \({\upbeta }_{1}\) reflects the direct effect of environmental protection behavior on subjective well-being under the condition of controlling for mediating variables.

For the convenience of later explanation, subjective well-being is considered a continuous variable and is identified in the mediating effect analysis using OLS regression. At this point, the mediating effect of happiness experience triggered by farmers' environmental protection behavior is equal to the indirect effect, which is the product of the coefficients \({\upbeta }_{2}{\updelta }_{1}\) and satisfies the relational equation \({\mathrm{\alpha }}_{1}={\upbeta }_{1}+{\upbeta }_{2}{\updelta }_{1}\) with the direct effect and the total effect. According to the stepwise test procedure, the simultaneous significance of \({\mathrm{\alpha }}_{1}\), \({\updelta }_{1}\) and \({\upbeta }_{2}\) implies a mediating effect, and if \({\upbeta }_{1}\) is also significant, it is considered to be partially mediated, and vice versa, it is fully mediated.

4 Empirical Results

4.1 Descriptive Statistical Analysis

Table 2 reports the means and standard deviations of the variables and gives the results of significance tests to compare means between groups. In particular, the low degree of participation group is the group of farmers with environmental protection behavior scores less than or equal to 1. Those with scores greater than 1 are the high participation group. Overall Chinese farmers have a subjective well-being score of 3.780, close to the comparative well-being level. Further group comparisons show that the subjective well-being of farmers with low involvement in environmental protection behavior is 3.746, lower than the high involvement group's 3.826. This difference is statistically significant at the 1% level, indicating a significant positive correlation between farmers' environmental protection behavior and subjective well-being. From the comparison of other variables, the differences between groups in self-rated health, social interaction, household income, education, and work status were all statistically significant, at least at the 5% level, and the highly involved group was significantly better than the low involved group in the above characteristics; the older farmer or the spouse, the lower the level of involvement in environmental protection behavior, and this difference was also significant at least at the 10% level.

4.2 Baseline Regression Analysis

Table 3 reports the estimation results for farmers' environmental protection behavior as both a dummy variable (en_pb) and a continuous variable (enpb), where models (1) and (4) are OLS regressions, (2) and (5) are ordered Logit estimations, and (3) and (6) are ordered Probit estimations. From the baseline regression results, both dummy and continuous variables, enhancing environmental protection behavior participation lead to higher subjective well-being experience of farmers, and hypothesis 1 is verified. In addition, the environmental improvements resulting from farmers' participation in environmental protection behavior have positive externalities, which can significantly facilitate the exchange and interaction of environmental experiences among individuals, enhancing their ability to reap more subjective well-being from the social support of family and friends.

The estimation of control variables was generally consistent with the findings of the existing literature (Jiang et al., 2012). Among them, farmers with better performance in self-rated health, social interaction, social trust, and perception of environmental governance would have higher happiness experiences; the effects of household income and education on farmers' subjective well-being were significant; farmers with spouses have better happiness experiences; age and subjective well-being show a U-shaped relationship. Unlike Graham and Felton's (2006) study, Chinese male farmers face more intense physical labor and experience less subjective well-being than women. In contrast, the subjective well-being of unemployed urban residents decreases (Appleton et al., 2008), and farmers who do not work are higher than those who do.

Based on the regression results of the ordered Probit model (6), we further estimated the marginal probabilities of environmental behavior and plotted Fig. 1. The results show that the marginal possibilities of farmers' environmental protection behaviors at different levels of subjective well-being are statistically significant, at least at the 5% level. The marginal probabilities corresponding to numbers 1, 2, and 3 are all negative, indicating that decreasing participation in environmental protection behavior decreases farmers' happiness experiences. The marginal probabilities corresponding to numbers 4 and 5 are all positive, implying that increasing participation in environmental protection behavior increases farmers' happiness experiences. Under the condition that other variables remain constant, for every 1-unit increase in farmers' participation in environmental protection behavior, their probability of having very unhappiness, relatively unhappiness, and say-not-happiness unhappiness experiences will decrease by 0.23%, 0.75%, and 0.97% on average. In comparison, the probability of having a relatively happy and very happy experience will increase by 0.62% and 1.33% on average. Hypothesis 2 is thus fully confirmed.

4.3 Robustness Tests

4.3.1 Instrumental Variables Regression

One issue that should not be overlooked is that individuals with higher subjective well-being levels also tend to have more frequent environmental protection behavior (Brown et al., 2005). Therefore, we chose a two-step regression of the instrumental variables to verify further the robustness of the "happiness effect" of farmers' environmental protection behavior. The CGSS questionnaire tested respondents' knowledge of environmental protection, consisting of 10 knowledge questions and their perception of environmental issues, which asked 12 categories of environmental issues in turn. Each question scored 1 point for a correct answer and 0 points for the others. The reliability of the indexes was examined, and the Cronbach's coefficients were 0.622 and 0.905, respectively, which could be processed cumulatively. We further reduced the two indicators of environmental knowledge (iv1) and environmental perception (iv2) to continuous variables with values in the range of 0–5 and 0–6 to reduce the effect of the difference in magnitude. Strong environmental protection knowledge and correct environmental cognition contribute to individual environmental protection behavior participation and do not directly lead to increased subjective well-being. We conducted a preliminary test by introducing instrumental variables into the subjective well-being equation and found that the coefficient estimates were not significant.

We first test the instrumental variables' validity within a two-step OLS framework, where the Kleibergen-Paap statistic is 133.43, much larger than the critical value of 19.93 under 10% bias, rejecting the weak instrumental variables hypothesis. The critical probability of the Hansen J statistic is 0.34, with no over-identification problem. Model (1) in Table 4 reports the linear regression results of the first stage, and models (2) and (3) are the results of OLS and ordered Probit of the second stage, respectively. It is easy to see that environmental protection knowledge and environmental awareness are significantly and positively correlated with farmers' environmental behavior, with each increase of 1 point leading to an increase of 0.12 and 0.10 points in participation in environmental protection behavior, respectively. After adding the instrumental variables, the regression coefficients are significantly more significant than the baseline regression coefficients for both linear and nonlinear models, suggesting that environmental protection behavior does have some endogeneity issues. Still, it does not overturn the "happiness effect" of farmers' environmental protection behavior. Hypothesis 1 is further verified.

4.3.2 Adjusted Sample Regression

The sample for this paper was obtained through a secondary sampling of the 2013 CGSS data, in which 61.64% of farmers were relatively happy. Therefore, we under-sampled the comparative happiness sample and controlled its distribution at 50% as the first experimental group. The non-sampled comparative happiness sample was combined with the second experimental group of other happiness categories. Models (4) and (5) in Table 4 show the results of the ordered Probit model estimates for the first and second experimental groups, both of which have significant positive coefficient estimates of environmental protection behavior at least at the 5% statistical level. It indicates that the estimates of the core variables were not significantly affected by the bias in the subjective well-being distribution.

In addition, we sampled farmers from the CSS2019 data. We measured the variables of interest using survey questions similar to CGSS2013, where environmental protection behavior was a dichotomous variable with participation assigned a value of 1 and non-participation assigned a value of 0. Model (6) in Table 4 reports the results of the ordered Probit model estimation based on CSS2019 data, and the estimates of the environmental protection behavior coefficients are significantly positive at the 5% statistical level. This indicates that the happiness effect of farmers' environmental behavior still obtains empirical evidence in the most recent years of the sample, and the above results have good robustness.

5 Extended Analysis

5.1 Heterogeneity Analysis

An interesting issue is that differently motivated environmental protection behaviors may lead to different subjective well-being experiences. This led to a further division into private (enpb1) and public (enpb2) environmental protection behaviors based on the 10 questions in the Environmental Behavior Scale. Personal environmental protection behaviors mainly reflect individual compliance with government regulations. They include five topics: "separate garbage," "discuss environmental protection issues with relatives and friends," "bring shop** bags when purchasing daily goods," "reuse plastic bags," and "proactively pay attention to environmental issues and environmental protection information". The public's environmental protection behavior is mainly reflected in individual participation in environmental protection campaigns. They include five topics: "donating money for environmental protection", "actively participating in environmental education activities organized by the government and organizations", "actively participating in environmental protection activities organized by private environmental groups", "maintaining woods or green areas at their own expense", and "actively participating in complaints and appeals to solve environmental problems". Both variables were measured using score accumulation and further reduced to continuous variables taking values in the range of 0–5. Table 5 reports the results of ordered Probit estimation for the two types of environmental protection behaviors in the overall male, female, adult, and elderly (60 years and older) samples.

The model (1) estimation in Table 5 shows that the effect of farmers' private environmental protection behavior on subjective well-being is significantly positive at the 10% level, and no statistical evidence was obtained for the positive impact of public environmental protection behavior. This suggests that environmental protection behavior with different motivations produces different happiness experiences, and private environmental protection behavior leads to more happiness experiences for farmers. In the total sample, the participation rate of personal environmental protection behavior reached 92%, while the participation rate of public environmental protection behavior was only 32%. The divergence of the well-being effect of environmental protection behavior also appears in the female and adult groups. Models (3) and (4) in Table 5 exhibit similar estimation results to the full sample, i.e., private environmental behavior is significant while public environmental behavior is insignificant. However, the estimation results for both types of environmental protection behavior in models (2) and (5) in Table 5 are insignificant. It indicates that male and older farmers have poorer well-being experiences in environmental protection behavior. The possible reason for this is that in rural China's intra-household division of labor, men take on more heavy agricultural work and find it difficult to participate in more environmental protection activities on their own. If environmental protection behavior does not fully reflect the individual's will to choose, the happiness experience is also significantly reduced. In addition, due to their health status, older adults may be disadvantaged in independent choice of participation in environmental protection behavior.

5.2 Moderating Effects Analysis

Models (1) to (4) of Table 6 report the estimation results of single and multiple moderating effects, respectively. The estimates of the single moderating effect show that the estimated coefficients of the interaction term between environmental governance, household income, and environmental protection behavior are very small and insignificant. In contrast, the interaction term coefficient between educational attainment and environmental protection behavior is statistically significant and negative at 10%. These estimates still hold in the multiple moderating effect framework. In other words, the relationship between environmental governance perceptions and household income did not significantly affect the relationship between farmers' environmental protection behavior and subjective well-being. Still, increased education decreased the well-being effect of environmental protection behavior, and hypothesis 3 was thus partially tested. The environmental governance variable is measured by asking respondents about their subjective evaluation of local government environmental policy implementation effectiveness. It reflects more on their perceived comparison of environmental regulation and environmental quality, which may appear to have opposite moderating effects on environmental protection behavior. The altruistic nature of environmental behavior allows farmers to experience the same experience from environmental protection behavior even if they have different income statuses. The happiness effect of farmers' environmental protection behaviors slowly decreases with increasing education, with an average of 0.04. This is because the highly educated farmers' group has higher expectations of quality of life and is driven more by external factors such as material rewards and experience skills, thus leading to relatively weaker happiness experiences from their environmental protection behavior than most less-educated groups.

5.3 Mediating Effects Analysis

The OLS baseline regressions in Table 3 estimate the direct effects of environmental protection behavior, while Table 7 further reports the estimates of the mediator and total effect equations. The results showed that both environmental protection behavior and the mediating variables were significant, at least at the 5% level in all three models, thus judging that there was indeed a partial mediating effect of farmers' environmental protection behavior, and hypothesis 4 was initially tested. Specifically, the marginal effects of farmers' environmental protection behavior on self-rated health, social interaction, and social trust were 0.075, 0.107, and 0.053, respectively. The positive impact of the three mediating variables on subjective well-being was also highly significant. On the one hand, environmental protection behaviors are characteristic of environmental risk avoidance and help farmers maintain good health and thus sustain a richer happiness experience. On the other hand, environmental protection behavior is altruistic, and farmers can enhance social interactions through participation in environmental activities. In the process, they can gain more social support and thus enhance their happiness experiences (Lee, 2019).

Next, we decompose and test the mediating effects using a Monte Carlo (MC) approach based on the SEM model. The results are shown in Table 8. Both the Sobel test and the MC test, the mediating effects of self-rated health, social interaction, and social trust, passed the test at least at the 5% level, and the 95% confidence interval did not contain a value of 0. This suggests at least three robust mediating transmission paths for farmers' environmental protection behavior, and hypothesis 4 was further confirmed. Conditional on controlling for other variables, the transmission effect of self-rated health was the most prominent at 21.5%; social interaction was relatively weaker than self-rated health, but the proportion still reached 14.3%; social trust had the lowest mediating contribution at 9.7%.

6 Conclusions

This paper raises the question of whether environmental protection behavior contributes to farmers' subjective well-being and conducts a systematic and robust empirical analysis using data from a representative CGSS survey in China. The first important finding suggests that farmers' environmental protection behavior can directly trigger subjective well-being experiences in the process of building a beautiful countryside in China. And the marginal probability effect is more pronounced at higher levels of subjective well-being. Secondly, farmers' subjective well-being experiences in environmental protection mainly come from private environmental protection behavior. In contrast, the participation rate in public environmental protection behavior is low, and subjective well-being experiences are relatively poor. Again, the association between farmers' environmental protection behavior and subjective well-being is negatively moderated by educational attainment. The moderating effect of household income does not support the idea that the association between environmental protection behavior and subjective well-being is subsequently weakened (Dulin et al., 2012) but is consistent with the "class equality effect". Finally, there is an indirect happiness effect of farmers' environmental protection behavior, which can enhance subjective well-being by improving health, social interaction, and trust. This finding reflects the broader significance of farmers' environmental protection behavior on subjective well-being. This is because active participation in environmental protection improves the individual's ability to avoid environmental risks and helps farmers improve their social interactions. Thus they continue to gain many good experiences, such as health, intimacy, belonging, and trust in a wide range of environmental protection behavior. These physical and mental experiences are undoubtedly an important source of subjective well-being.

The above findings have important practical significance for building beautiful villages and improving farmers' well-being. The policy implications are mainly reflected in the following two aspects. On the one hand, policymakers should pay attention to and increase the publicity of environmental knowledge and environmental cognition in the policy to improve farmers' environmental knowledge and cognitive ability. And then promote their better participation in environmental protection and reap rich and diverse subjective happiness experiences from it. On the other hand, the environmental protection campaign should pay attention to the participation of farmers. Through measures such as enriching the content of the environmental protection campaign and promoting the environmental protection campaign to the countryside, the farmers should better feel the relevance of public environmental protection actions to their interests and increase their initiative and enthusiasm to participate. In addition, China is a typical representative of develo** countries. An important characteristic of rural China is that it has a large number of people and a small amount of land and has developed a specific mode of production and way of life. Thus, this paper's findings and policy implications on the happiness effects of farmers' environmental protection behavior remain broadly applicable to countries with similar characteristics worldwide.

Notes

National Bureau of Statistics: Seventh National Population Census Bulletin (No. 7). http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/tjgb/rkpcgb/qgrkpcgb/202106/t20210628_1818826.html

References

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

Ambrey, C. L., & Fleming, C. M. (2011). Valuing scenic amenity using life satisfaction data. Ecological Economics, 72(12), 106–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2011.09.011

Appleton, S., & Song, L. (2008). Life satisfaction in urban China: Components and determinants. World Development, 36(11), 2325–2340. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2008.04.009

Arampatzi, E., Burger, M. J., & Novik, N. (2018). Social network sites, individual social capital and happiness. Journal of Happiness Studies, 19(1), 99–122. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-016-9808-z

Barkan, S. E. (2004). Explaining public support for the environmental movement: A civic voluntarism model. Social Science Quarterly, 85(4), 913–937. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0038-4941.2004.00251.x

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173

Bradley, G. L., Babutsidze, Z., Chai, A., & Reser, J. R. (2020). The role of climate change risk perception, response efficacy, and psychological adaptation in pro-environmental behavior: A two nation study. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 68(4), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2020.101410

Breslow, S. J., Sojka, B., Barnea, R., et al. (2016). Conceptualizing and operationalizing human well-being for ecosystem assessment and management. Environmental Science & Policy, 66(12), 250–259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2016.06.023

Brown, K. W., & Kasser, T. (2005). Are psychological and ecological well-being compatible? The role of values, mindfulness, and lifestyle. Social Indicators Research, 74(2), 349–368. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-004-8207-8

Cui, H. Z. (2015). Analysis of factors influencing subjective well-being of rural elderly people–based on questionnaire survey data of farm households in eight provinces (districts) nationwide. China Rural Economy, 04, 72–80.

Costanza, R. (1989). What is ecological economics. Ecological Economics, 1(1), 1–7.

Diekmann, A., & Franzen, A. (1999). The wealth of nations and environmental concern. Environment and Behavior, 31(4), 540–549. https://doi.org/10.1177/00139169921972227

Dulin, P. L., Gavala, J., Stephens, C., Kostick, M., & McDonald, J. (2012). Volunteering predicts happiness among older Māori and non-Māori in the New Zealand health, work, and retirement longitudinal study. Aging & Mental Health, 16(5), 617–624. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2011.641518

Dunlap, R. E., & Mertig, A. G. (1995). Global concern for the environment: Is affluence a prerequisite? Journal of Social Issues, 51(4), 121–137. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.1995.tb01351.x

Dunlap, R. E., & York, R. (2008). The globalization of environmental concern and the limits of the postmaterialist values explanation: Evidence from four multinational surveys. The Sociological Quarterly, 49(3), 529–563. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1533-8525.2008.00127.x

Easterlin, R. A. (1974). Does economic growth improve the human lot? Some empirical evidence. Nations and Households in Economic Growth. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-205050-3.50008-7

Franzen, A., & Meyer, R. (2010). Environmental attitudes in cross-national perspective: A multilevel analysis of the ISSP 1993 and 2000. European Sociological Review, 26(2), 219–234. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcp018

Frey, B. S., Luechinger, S., & Stutzer, A. (2009). The life satisfaction approach to valuing public goods: The case of terrorism. Public Choice, 138(3), 317–345. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-008-9361-3

Frey, B. S., & Stutzer, A. (2002). What can economists learn from happiness research? Journal of Economic Literature, 40(2), 402–435. https://doi.org/10.1257/002205102320161320

Galbraith, J K. (1998). The affluent society. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 142.

Gowdy, J. (2005). Toward a new welfare economics for sustainability. Ecological Economics, 53(2), 211–222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2004.08.007

Graham, C., & Felton, A. (2006). Inequality and happiness: Insights from Latin America. Journal of Economic Inequality, 4(1), 107–122. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10888-005-9009-1

Harris, P. G. (2008). Green or brown? environmental attitudes and governance in greater china. Nature and Culture, 3(2), 151–182. https://doi.org/10.3167/nc.2008.030202

Hu, H. B., & Wang, Q. (2022). Does participation in commercial insurance improve household subjective well-being: a theoretical mechanism and an empirical test. Macroeconomic Research, 10, 66–87.

Huerta, C. M., & Utomo, A. (2021). Evaluating the association between urban green spaces and subjective well-being in Mexico city during the COVID-19 pandemic. Health & Place, 70(7), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2021.102606

Jiang, S., Lu, M., & Sato, H. (2012). Identity, inequality, and happiness: Evidence from urban China. World Development, 40(6), 1190–1200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2011.11.002

Kaklauskas, A., Dias, W., Binkyte-Veliene, A., et al. (2020). Are environmental sustainability and happiness the keys to prosperity in Asian nations? Ecological Indicators, 119(4), 1–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2020.106562

Katsumi, Y., Kondo, N., Dolcos, S., et al. (2021). Intrinsic functional network contributions to the relationship between trait empathy and subjective happiness. NeuroImage, 227(2), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2020.117650

Keyes, C. L. (2006). Subjective well-being in mental health and human development research worldwide: An introduction. Social Indicators Research, 77(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-005-5550-3

Kim, M., & Stepchenkova, S. (2020). Altruistic values and environmental knowledge as triggers of pro-environmental behavior among tourists. Current Issues in Tourism, 23(13), 1575–1580. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2019.1628188

Kislev, E. (2020). Social capital, happiness, and the unmarried: A multilevel analysis of 32 European countries. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 15(5), 1475–1492. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-019-09751-y

Knight, J., & Gunatilaka, R. (2010a). Great expectations? The subjective well-being of rural-urban migrants in China. World Development, 38(1), 113–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2009.03.002

Knight, J., & Gunatilaka, R. (2010b). The rural-urban divide in China: Income but not happiness? The Journal of Development Studies, 46(3), 506–534. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220380903012763

Knight, J., Song, L., & Gunatilaka, R. (2009). Subjective well-being and its determinants in rural China. China Economic Review, 20(4), 635–649. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2008.09.003

Krekel, C., MacKerron, G. (2020). How environmental quality affects our happiness. World Happiness Report.

Larsen, R. J., Diener, E. D., & Emmons, R. A. (1985). An evaluation of subjective well-being measures. Social Indicators Research, 17(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00354108

Lee, M. A. (2019). Volunteering and happiness: Examining the differential effects of volunteering types according to household income. Journal of Happiness Studies, 20(3), 795–814. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-018-9968-0

Leite, Â., Sousa, H. E., Vidal, D. G., & Dinis, M. A. P. (2020). Finding a path for happiness in the context of sustainable development: A possible key. International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology, 27(5), 396–404. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504509.2019.1708509

Li, F., & Zhou, T. (2020). Effects of objective and subjective environmental pollution on well-being in urban China: A structural equation model approach. Social Science & Medicine, 249(3), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.112859

Lorente, D. B., & Álvarez, A. (2016). Economic growth and energy regulation in the environmental Kuznets curve. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 23(16), 16478–16494.

Mackerron, G., & Mourato, S. (2013). Happiness is greater in natural environments. Global Environmental Change, 23(5), 992–1000. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2013.03.010

Marquart-Pyatt, S. T. (2007). Concern for the environment among general publics: A cross-national study. Society & Natural Resources, 20(10), 883–898. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920701460341

Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50(4), 370–396. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0054346

Oswald, A. J. (1997). Happiness and economic performance. The Economic Journal, 107(445), 1815–1831. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0297.1997.tb00085.x

Qiu, H., & Zhang, L. Y. (2021). Heterogeneity in the educational attainment of Chinese youth and its impact on subjective well-being. Journal of Population, 43(06), 85–93.

Ram, R. (2009). Social capital and happiness: Additional cross-country evidence. Journal of Happiness Studies, 11(3), 409–418. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-009-9148-3

Rehdanz, K., Welsch, H., Narita, D., & Okubo, T. (2015). Well-being effects of a major natural disaster: The case of Fukushima. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 116(8), 500–517. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2015.05.014

Rizkallah, W. W. A. (2021). The impact of fiscal policy on economic happiness: Evidence from the countries of the MENA region. Review of Economics and Political Science, 6(2), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1108/REPS-07-2020-0086

Samuelson, P. A. (1948). Economics. McGraw Hill Higher Education.

Sia, A. P., Hungerford, H. R., & Tomera, A. N. (1986). Selected predictors of responsible environmental behavior: An analysis. The Journal of Environmental Education, 17(2), 31–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/00958964.1986.9941408

Stern, P. C. (2005). Understanding individuals’ environmentally significant behavior. Envtl. l. Rep. News & Analysis, 35(11), 10785–10790.

Tang, Y. M., & Geng, L. N. (2017). A study on the relationship between environmental behavior and multidimensional well-being. Youth Exploration, 04, 50–60.

Wang, H. Y., **a, Y., Sun, D. S., Zhang, L., & Wei, H. (2021). Meta-analysis of factors influencing farmers’ subjective well-being in China. China Agricultural Resources and Zoning, 42(06), 203–214.

Weinhold, D. (2013). The happiness-reducing costs of noise pollution. Journal of Regional Science, 53(2), 292–303. https://doi.org/10.1111/jors.12001

Wilson, E., & Mukhopadhyaya, P. (2020). The all-you-can-eat economy: How never-ending economic growth affects our happiness and our chances for a sustainable future. World, 1(3), 216–226. https://doi.org/10.3390/world1030016

Yang, J. S., Xu, J., & Wu, X. G. (2013). Economic growth and environmental and social health costs. Economic Research, 48(12), 17–29.

Yuan, Z., & Li, L. (2017). Marriage and happiness: Chinese microdata based on WVS. China Economic Issues, 01, 24–35. https://doi.org/10.19365/j.issn1000-4181.2017.01.03

Zhan, Y. Q., Wang, J., & Tao, Y. Y. (2021). Identity, urbanization level, and environmental protection behavior of agricultural migrants. China Economic Issues, 05, 73–88.

Zhang, P., & **, Y. J. (2016). The influence of mass media on environmental protection behavior of urban and rural residents in China–based on data from the 2013 China Integrated Social Survey. Journal of the Renmin University of China, 30(04), 122–129.

Zhang, Y. L., & Xu, Y. D. (2020). Rural public service provision and residents’ subjective well-being. Journal of Agricultural and Forestry Economics and Management, 19(01), 98–108. https://doi.org/10.16195/j.cnki.cn36-1328/f.2020.01.10

Zhou, F. C. (1987). Selected works on Western ethics (p. 103). The Commercial Press.

Funding

The research leading to these results received funding from the National Social Science Fund of China under Grant Agreement No (21CJL018). Project of Basic Research Business Fund of Jilin University (2019QY016). National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 71903031).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

WQ: Conception, Methodology, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing, Fund acquisition. WX: Software, Review, Editing, Fund acquisition. XQ: Method, Visualization, Editing. MS: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing—original draft, Software, Writing—review & editing, Fund acquisition.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts to report.

Informed consent

The research is not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Qi, W., Xu, W., Qi, X. et al. Can Environmental Protection Behavior Enhance Farmers' Subjective Well-Being?. J Happiness Stud 24, 505–528 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-022-00606-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-022-00606-2