Abstract

Black women experience disproportionate rates of advanced breast cancer diagnoses and mortality. Mammography is a proven and effective tool in early breast cancer detection and impacts patient outcomes. We interviewed Black women with a personal or family history of breast and/or ovarian cancer to understand their screening experiences and views. N = 61 individuals completed an interview. Interview transcripts were qualitatively analyzed for themes regarding clinical experiences, guideline adherence, and family sharing specific to Black women and their families. Most participants were college educated with active health insurance. Women in this cohort were knowledgeable about the benefits of mammography and described few barriers to adhering to annual mammogram guidelines. Some with first-degree family history were frustrated at insurance barriers to mammography before the age of 40. Participants were generally comfortable encouraging family and friends to receive mammograms and expressed a desire for a similar screening tool for ovarian cancer. However, they expressed concern that factors such as screening awareness and education, lack of insurance coverage, and other systematic barriers might prevent other Black women from receiving regular screening. Black women in this cohort reported high adherence to mammography guidelines, but expressed concern about cultural and financial barriers that may impact cancer screening access in the population more generally and contribute to disparities. Participants noted the importance of frank and open discussions of breast cancer screening in their families and community as a means of improving awareness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In 2019, breast cancer became the leading cause of cancer death for African American/Non-Hispanic Black (“Black”) women [1]. Although Black and non-Hispanic White (NHW) women have a similar incidence of breast cancer, Black women have a 41% higher mortality rate [2]. Black women also experience lower survival rates for ovarian cancer [1, 3]. Because there are no effective screening options for ovarian cancer approximately 70% of patients are diagnosed at an advance stage [1].

Mammography rates in higher socioeconomic status (SES) Black patient populations are equal to those of NHW women, but this changes as SES is lowered [4,5,6]. Cultural, demographic, and structural factors influence breast screening in Black communities, including fears and medical mistrust, age, education, religious beliefs, and access to medical care, including insurance coverage and established care [7,8,9,10,11,12]. Besides SES, some studies suggest that the perception of racial discrimination by the medical system has an impact on mammography uptake in Black communities [6, 8]. Other studies suggest community-based efforts and outreach may greatly influence mammography rates in these communities [8, 13]. To explore these factors, we conducted a community-engaged qualitative study to explore the screening perceptions and clinical experiences of Black women with a personal diagnosis or family history of breast or ovarian cancer.

Methods

Community Engagement

In accordance with principles of community-engaged research [14], the research team established a community advisory board (CAB). The board was composed of 8–12 members of the Coalition of Blacks Against Breast Cancer (CBBC), a nonprofit organization providing cancer education and support primarily for Black women with a personal diagnosis or family history of breast cancer. Membership also included allied health professionals and community advocates. The CAB met monthly to review the interview guides, recruitment materials, and provide feedback on preliminary results.

Recruitment

Participants were recruited through social media platforms of patient support organizations including CBBC, the National Ovarian Cancer Coalition, and the Sister’s Network of Southeast Florida; historically Black sororities and professional organizations; and through snowball recruitment. Eligible patients from Mayo Clinic’s Cancer Center were also invited to participate. Study eligibility was determined via an online screening survey or verified by the research team. Inclusion criteria consisted of self-identifying as Black or African American, female, 18 + years old, English speaking, and a personal diagnosis or a biological relative with a breast and/or ovarian cancer diagnosis. After completing a written consent, participants were scheduled for a telephone or video conference interview. After the interview, participants were sent a gift basket curated in cooperation with the CAB in appreciation for their participation. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Mayo Clinic.

Data Collection

The study team developed two interview guides tailored to the experience of a personal or family member diagnosis. Study team members included experience in oncology, community engagement, patient experience, epidemiology, and bioethics. Interview guides were also reviewed and modified by the CAB. One researcher with experience in qualitative methods and breast cancer research conducted semi-structured interviews from September 2020 – April 2021. Topics included experiences with cancer diagnosis, cancer support, the medical system, cancer screening, and views on genetic testing for cancer risk and research participation. Follow-up questions were asked at the interviewer’s discretion. Interviews were conducted until thematic saturation was reached. The average interview with participants with a personal diagnosis was 82 min (range 43–152 min) and 62 min (range 42–89 min) for family members. Interviews were audio-recorded with permission (n = 60), de-identified, and transcribed verbatim by a professional transcriptionist.

Data Analysis

Data analysis was conducted in accordance with the principles of grounded theory [15]. Two researchers developed two codebooks based on iterative themes from randomly selected interview transcripts, one for those with a personal diagnosis (n = 4, 9.3%) and one for family members (n = 2, 11.1%). Transcripts were divided between three researchers (n = 24, 39.3%; n = 16, 26.2%; n = 8, 13.1%) and coded using the software program NVivo 12. An additional n = 13 (21.3%) transcripts were intermittently coded to consensus by at least two researchers for coding accuracy and consistency. Codes were discussed weekly for emerging themes and trends. Here we discuss thematic analysis related to codes on cancer screening in Black communities. Representative quotes are provided according to published guidelines on reporting qualitative research with minimal editing for readability [16]. Given the genetic link between hereditary breast and ovarian cancer syndrome and participant family histories, we present findings on cancer screening from participants affected by both cancer types.

Results

Study Cohort

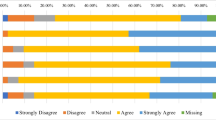

A total of 89 individuals met inclusion criteria and were invited to participate in an interview. Of those, 66 (74%) completed the consent form and 61 (69%) completed an interview; 43 (70%) participants had a personal diagnosis and 18 (30%) had a family member diagnosed with breast or ovarian cancer. Table 1 represents participant demographics.

Breast Screening Adherence and Clinical Experience

Participants described a range of self and medical screening procedures. A small number (n = 9) reported conducting self-breast exams; self-breast exams were generally described as being performed with less consistency. Those who identified a suspicious lump often discovered it incidentally.

I just happened to wake up one morning, and I was actually laying on my left side, and I just touched myself. I was like, “Oh, what is that?” (…) I was not good about that [self-breast exams].

-Breast Cancer Diagnosis

Women aware of their increased risk of breast cancer from either personal medical history or a family history of breast cancer started screening in their mid-30’s. A few started in their 20’s at the recommendation of their physician. Those who had dense breasts reported higher vigilance in completing recommended screenings.

I wanna say early 20s, went for my gynecological exam and when they felt my breasts, they thought they were meaty. At that time, it was my mother and two sisters [diagnosed with breast cancer], so three incidences and they sent me for my first mammogram then.

-Family Member Diagnosed with Breast Cancer

Yes, all the time because in my diagnosis, they kept tellin’ me that my breasts were dense. Sometimes the mammogram isn’t gonna catch everything. We, who have dense breasts, have to ask additional questions. Do you have the right angle? Can you see everything? Do you need to do a color testing?

-Breast Cancer Diagnosis

Some participants believed their baseline risk was low, based on a lack of known family history, but discovered a more extensive family history after their own diagnosis.

If my mother had had breast cancer, I would have definitely let my gynecologist know that so that I could have something maybe other than the annual mammogram. I don’t know what it is. I didn’t have a history, so I didn’t feel that cancer screening was important in my case other than the mammogram.

-Breast Cancer Diagnosis

Study participants indicated minimal barriers to accessing mammograms and felt comfortable discussing it with their physician. Some stated that their physician strongly recommended a mammogram before the age of 40 due to family history, but they were prevented from doing so due to lack of insurance coverage. A few chose to pay out of pocket out of concern for their own risk.

The doctor… would ask me if I had ever gotten [a mammogram]…with the age limit or the cutoff, they—I just never got one. They were just saying, well, maybe ‘cause of your family history, maybe you should consider getting a mammogram earlier than later.

-Family Member Diagnosed with Breast Cancer

You couldn’t do it till you were 40, or you had to fight with [insurance] to get it done. I had had a lump on my right breast about three years earlier and I had to fight with them to do that and I had to pay out of pocket to get that screening done.

-Breast Cancer Diagnosis

Most participants indicated that they were able to obtain regular mammograms from their provider without difficulty, and only one used a free breast cancer screening clinic to obtain a mammogram. A few reported delays between annual mammograms due to changes in employment, the COVID-19 pandemic, and family challenges that took precedence.

My insurance would not allow screening. I could only do a mammogram when I had a problem. Sometimes there were free mammograms that I would take advantage of and go into the community and get a mammogram.

-Breast Cancer Diagnosis

Some participants noted their privilege in relatively easy access to mammograms and other cancer screenings, noting that other Black women face financial and logistical barriers to accessing preventative care.

We know that African American women when you’re talkin’ about screening, we’re still not gettin’ those screenings like other ethnicities. (…) If I need the screening, I get in my car and drive (…) think about the difference in somebody that has to take off from work and take two or three buses to get someplace and get back. That’s a full day off of work.

-Breast Cancer diagnosis

I would want everyone to be more aware of early detection, and not be afraid to go, or go—like they can’t get a breast mammogram because they don’t have insurance.

-Breast Cancer Diagnosis

Perceptions of Breast and Ovarian Cancer Screening

Almost all participants stressed the importance of regular breast screening. Benefits cited included setting a baseline for future breast changes, heightened screening of dense breast tissue, and detection of neoplasms.

Screening…would [increase] that awareness… that awareness would also say, “If you have it or it’s coming, the treatment is there the earlier you are aware that it’s there.” Be prepared. There’s help if you do something early. Don’t be afraid.

-Family Member Diagnosed with Breast Cancer

Specifically, participants conveyed a perception that the earlier breast cancer was detected the more likely treatment would lead to a favorable outcome. They expressed concerns about the lack of discussion of cancer screening in their communities.

Make sure you check yourselves on a regular basis, and make sure you go in for your screenings once a year, because it can literally save your life.

-Breast Cancer Diagnosis

A lot just with people of color, things aren’t detected at the time that they should be, and a lot can be saved and mitigated, or at least not progress with early detection, so I’m open to it [discussing cancer screening]. I know that my community doesn’t necessarily—these aren’t conversations that are had in families.

-Family Member Diagnosed with Ovarian Cancer

Ovarian cancer survivors noted that while mammograms were advantageous for identifying breast cancer, they were frustrated that there was no equivalent screening for ovarian cancer. Some felt CA125 screening should be offered to all women for routine screening given its role in diagnosing and/or monitoring their own cancer.

For ovarian, it’s the unknown secret ‘cause you just don’t know. You really don’t. Had I not gone through emergency, I probably wouldn’t be here today.

-Ovarian Cancer Diagnosis

When our blood test is taken at these annual exams, throw in the one for the CA-125 with our permission, I guess. I think people need to know. To me, that would end a lot of stage fours and twos and threes and catch it early.

-Ovarian Cancer Diagnosis

A small number of participants believed they were being screened for ovarian or uterine cancer as part of their annual gynecological exam (i.e., Pap smear).

I’m not sure what other ways they screen for cancer, but I’m assuming that it’ll show up with the ovarian, [on] your Pap smear.

-Family Member Diagnosed with Ovarian Cancer

Challenges Associated with Discussing Cancer Screening

Women described several barriers to discussing the importance of cancer screening and encouraging adherence in their family and community. One was a perception of cancer diagnosis as an equivalent to death. Some participants stated that within their social networks there is a belief that cancer is something that happens to “other people” or a sense that “what you don’t know can’t hurt you.”

It’s almost like I would rather not know. Generally, I think is the general consensus about it. If I don’t know, it’ll make it go away, almost. That kinda deal.

-Breast Cancer Diagnosis

Ovarian cancer, we’ve never had that in our family, as far as back as we can remember or as far back as we know. It could’ve been, and we just didn’t know it. Just outta the blue. You’re the first one in the whole family.

-Ovarian Cancer Diagnosis

Several participants made a point to discuss cancer screening with their family and friends. Most felt that their family and friends were generally receptive to these conversations. It was less common to discuss cancer screening with male relatives. A small number stated that they never discussed cancer screening with anyone, typically because it did not come up.

I might say to my daughter, “When’s the last time you had your mammogram,“ and that’s it. Make sure you don’t miss your mammogram. You’re getting your mammograms, and stuff like that.

-Breast Cancer Diagnosis

Some expressed that discussing cancer screening with a healthcare provider may carry more weight than discussions with family or community members, especially if they had an established relationship.

I think medical professionals—I think those—sometimes people put out pamphlets or whatever. I think that’s useful (…) any opportunity for anyone to get the information is good, but I think a doctor is really good—or a medical professional.

-Breast Cancer Diagnosis

I would probably say maybe through their doctor, and I don’t think it’d necessarily have to be a primary, whoever they have the best relationship with.

-Breast Cancer Diagnosis

Discussion

In this cohort, participants described diligence in completing recommended mammograms and other cancer screening modalities, but described broader concerns about practical and cultural barriers that may contribute to screening accessibility and uptake. These results are consistent with reports of high adherence to mammography within higher socioeconomic status and well-educated Black populations [5, 17, 18]. Healthcare infrastructure and insurance claims remained a common frustration and obstacle for women seeking screening and is a significant factor in mammography adherence and uptake [4]. Participants with first-degree relatives diagnosed at a young age or with an aggressive sub-type expressed frustration that their insurance did not cover mammography screening before the age of 40. Requiring insurance to cover mammograms and excluding mammograms from deductibles has been shown to increase mammography uptake by up to 25% in women 25–74 years of age [19]. While this cohort was mostly privately insured, participants expressed a perception that financial burden prevented accessibility for many Black women.

Several women expressed a desire for more provider-lead conversations on cancer screening and education, stressing their authority on health information. Physicians greatly influence the shared decision-making process for the initiation of cancer screening; one study found that while women expressed trust in their physicians to weigh their individual risk for breast cancer with screening guidelines, physicians had trouble discussing mammography with patients due to time constraints, adequate knowledge of screening risks, and conflicting screening guidelines [20]. Enhanced patient education on cancer screening may also be beneficial, including its present limitations for ovarian cancer, given the small number of participants who believed they received ovarian or uterine cancer screening via an annual Pap smear. A belief that screening has already been completed may deter individuals from seeking more specialty care, even when symptoms commence. Moreover, some participants with ovarian cancer history advocated for universal CA-125 testing and did not appear to be aware that standardized screening for ovarian cancer in asymptomatic women is discouraged [21, 22]. Lower CA-125 sensitivity and specificity and false positives stemming from benign gynecological conditions is documented in Black women [21, 23, 24]. Research on ethnic-specific cut-off values and patient education on the limitations of CA-125 is needed.

Many participants described a need to increase awareness of the importance of breast and ovarian cancer screening for Black women. Some addressed this need by personally advocating within their social networks and community. However, others stated that they never, or had extremely limited, discussions on cancer screening, including a small number with a diagnosis of breast cancer. Knowledge of their family cancer history was associated with their risk perception of develo** breast cancer. Those with known family history expressed greater vigilance in completing recommended cancer screening, consistent with findings that Black women with a known family history of breast cancer are 15% more likely to have had a mammogram within the last year [25], in addition to other studies demonstrating motivation to complete annual mammography following the breast cancer diagnosis of family or friends [26]. Family sharing of cancer diagnoses followed published patterns of health sharing occurring most commonly between family members with close personal relationships, usually along parallel gender identities [27]. Advanced age and concern for personal privacy are themes found in our results and current literature that pose additional obstacles to family cancer history sharing within Black populations [27]. Increasing family discussion of cancer histories and the importance of regular breast cancer screening is vital to increasing mammogram uptake.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest qualitative interview study of Black women with personal and family experience of breast and ovarian cancer. Qualitative interviews allowed for in-depth exploration of unanticipated topics. Recall bias may be a limitation; overestimation of self-reported mammography completion has been reported previously [28]. Study participants had greater educational attainment and were more likely to be privately insured than the national population. Individuals with lower SES and educational attainment may have different experiences. Several participants also participated in patient advocacy organizations and may have enhanced knowledge about cancer screening and clinical factors known to increase risk of breast and ovarian cancer. Further research is necessary to determine the prevalence and contents of breast screening conversations between Black women and their impact on screening adherence, including potential differences based on socioeconomic and educational differences.

Conclusion

Black women with a personal or family history of breast and/or ovarian cancer described adherence to mammography recommendations. However, their responses suggest that breast cancer screening awareness in Black families could be improved through greater patient education, the normalization of cancer history sharing, and discussions of the role of screening in reducing cancer morbidity.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Giaquinto, A. N., Miller, K. D., Tossas, K. Y., Winn, R. A., Jemal, A., & Siegel, R. L. (2022). Cancer statistics for african American/Black people 2022. C Ca: A Cancer Journal For Clinicians, 72, 202–229. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21718.

Yedjou, C. G., Sims, J. N., Miele, L., Noubissi, F., Lowe, L., Fonseca, D. D., Alo, R. A., Payton, M., & Tchounwou, P. B. (2019). Health and racial disparity in breast Cancer. Advances In Experimental Medicine And Biology, 1152, 31–49. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-20301-6_3.

Torre, L. A., Trabert, B., DeSantis, C. E., Miller, K. D., Samimi, G., Runowicz, C. D., Gaudet, M. M., Jemal, A., & Siegel, R. L. (2018). Ovarian cancer statistics, 2018. C Ca: A Cancer Journal For Clinicians, 68, 284–296. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21456.

Gathirua-Mwangi, W. G., Monahan, P. O., Stump, T., Rawl, S. M., Skinner, C. S., & Champion, V. L. (2016). Mammography Adherence in African-American Women: Results of a Randomized Controlled Trial. Annals Of Behavioral Medicine, 50, 70–78. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-015-9733-0.

Narayan, A., Fischer, A., Zhang, Z., Woods, R., Morris, E., & Harvey, S. (2017). Nationwide cross-sectional adherence to mammography screening guidelines: National behavioral risk factor surveillance system survey results. Breast Cancer Research And Treatment, 164, 719–725. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-017-4286-5.

Jacobs, E. A., Rathouz, P. J., Karavolos, K., Everson-Rose, S. A., Janssen, I., Kravitz, H. M., Lewis, T. T., & Powell, L. H. (2014). Perceived discrimination is associated with reduced breast and cervical cancer screening: The study of women’s Health across the Nation (SWAN). Journal of women’s health, 23, 138–145. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2013.4328. https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/full/.

Aleshire, M. E., Adegboyega, A., Escontrías, O. A., Edward, J., & Hatcher, J. (2021). Access to care as a barrier to Mammography for Black Women. Policy Polit Nurs Pract, 22, 28–40. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527154420965537.

Mouton, C. P., Carter-Nolan, P. L., Makambi, K. H., Taylor, T. R., Palmer, J. R., Rosenberg, L., & Adams-Campbell, L. L. (2010). Impact of perceived racial discrimination on health screening in black women. Journal Of Health Care For The Poor And Underserved, 21, 287–300. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.0.0273.

Russell, K., Swenson, M. M., Skelton, A. M., & Shedd-Steele, R. (2003). The meaning of health in mammography screening for african american women. Health Care For Women International, 24, 27–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/07399330390169981.

Agrawal, P., Chen, T. A., McNeill, L. H., Acquati, C., Connors, S. K., Nitturi, V., Robinson, A. S., Martinez Leal, I., & Reitzel, L. R. (2021). Factors Associated with breast Cancer screening adherence among Church-Going african American Women. International Journal Of Environmental Research And Public Health, 18, 8494. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18168494.

Guo, Y., Cheng, T. C., & Yun Lee, H. (2019). Factors Associated with adherence to preventive breast Cancer Screenings among Middle-aged african american women. Soc Work Public Health, 34, 646–656. https://doi.org/10.1080/19371918.2019.1649226.

Orji, C. C., Kanu, C., Adelodun, A. I., & Brown, C. M. (2020). Factors that Influence Mammography use for breast Cancer screening among african american women. Journal Of The National Medical Association, 112, 578–592. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnma.2020.05.004.

Ntiri, S. O., Klyushnenkova, E. N., & Bentzen, S. M. (2018). Outcomes of a community-based breast Cancer screening program in Baltimore City. Journal Of Health Care For The Poor And Underserved, 29, 898–913. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2018.0067.

Clinical and Translational Science Awards Consortium Community Engagement Key Function Committee Task Force on the Principles of Community Engagement. Principles of community engagement (2011). Available from: www.atsdr.cdc.gov/communityengagement/pdf/PCE_Report_508_FINAL.pdf

Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2014). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for develo** grounded theory (p. 456). SAGE Publications.

O’Brien, B. C., Harris, I. B., Beckman, T. J., Reed, D. A., & Cook, D. A. (2014). Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Academic Medicine, 89, 1245–1251. https://journals.lww.com/academicmedicine/fulltext/2014/09000/standards_for_reporting_qualitative_research__a.21.aspx.

Bandera, E. V., Lee, V. S., Rodriguez-Rodriguez, L., Powell, C. B., & Kushi, L. H. (2016). Racial/Ethnic disparities in Ovarian Cancer Treatment and Survival. Clinical Cancer Research, 22, 5909–5914. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-1119.

Srivastava, S. K., Ahmad, A., Miree, O., Patel, G. K., Singh, S., Rocconi, R. P., & Singh, A. P. (2017). Racial health disparities in ovarian cancer: Not just black and white. J Ovarian Res, 10, 58. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13048-017-0355-y.

Bitler, M. P., & Carpenter, C. S. (2016). Health insurance mandates, mammography, and breast cancer diagnoses. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 8, 39–68. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5844506.

DuBenske, L. L., Schrager, S., McDowell, H., Wilke, L. G., Trentham-Dietz, A., & Burnside, E. S. (2017). Mammography Screening: Gaps in Patient’s and Physician’s needs for Shared decision-making. The Breast Journal, 23, 210–214. https://doi.org/10.1111/tbj.12779.

Charkhchi, P., Cybulski, C., Gronwald, J., Wong, F. O., Narod, S. A., & Akbari, M. R. (2020). CA125 and ovarian Cancer: A Comprehensive Review. Cancers (Basel), 12, E3730. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers12123730.

**, J. (2018). Screening for ovarian Cancer. Journal Of The American Medical Association, 319, 624. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.22136.

Neogi, S. S., & Srivastava, L. M. (2014). Elevated tumour marker CA125: Interpretations in clinical practice. Current Medicine Research and Practice, 4, 214–218. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2352081714001408.

Sasamoto, N., Vitonis, A. F., Fichorova, R. N., Yamamoto, H. S., Terry, K. L., & Cramer, D. W. (2021). Racial/ethnic differences in average CA125 and CA15. 3 values and its correlates among postmenopausal women in the USA. Cancer Causes & Control, 32, 299–309. https://europepmc.org/articles/pmc7887701/bin/nihms1668896-supplement-1668896_sup_tab_1-2.docx.

Williams, K. P., Sheppard, V. B., Todem, D., Mabiso, A., Wulu, J. T., & Hines, R. D. (2008). Family matters in mammography screening among african-american women age > 40. Journal Of The National Medical Association, 100, 508–515. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0027-9684(15)31297-9.

Davis, C. M. (2021). Health beliefs and breast Cancer Screening Practices among African American Women in California. International Quarterly Of Community Health Education, 41, 259–266. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272684X20942084.

Thompson, T., Seo, J., Griffith, J., Baxter, M., James, A., & Kaphingst, K. A. (2015). The context of collecting family health history: Examining definitions of family and family communication about health among african american women. J Health Commun, 20, 416–423. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2014.977466.

Levine, R. S., Kilbourne, B. J., Sanderson, M., Fadden, M. K., Pisu, M., Salemi, J. L., Mejia de Grubb, M. C., O’Hara, H., Husaini, B. A., Zoorob, R. J., & Hennekens, C. H. (2019). Lack of validity of self-reported mammography data. Fam Med Community Health, 7, e000096. https://doi.org/10.1136/fmch-2018-000096.

Acknowledgements

We thank members of the ADdressing Views of African AmericaNs on CancEr Screening (ADVANCE) study community advisory board for their dedication and study feedback. We also thank Kristin Clift for her contributions to the data analysis. This publication was supported by Grant Number UL1 TR002377 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. We also wish to thank Dr. Gerardo Colon-Otero for additional financial support. We are grateful to our participants for sharing their stories and perspectives with us.

Funding

This project was supported by Mayo Clinic’s Breast and Ovarian Specialized Program of Research Excellence (SPORE)/Women’s Cancer Program Developmental Research Program award (Breast SPORE (P50 CA116201), the Ovarian SPORE (P50 CA136393) and Cancer Center Grant (P30 CA015083)).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethics Approval

Mayo Clinic’s Institutional Review Board approved this study as minimal risk (#20-006851).

Consent to Participate

All participants provided written consent to have their anonymous results used for research.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Rousseau, A., Riggan, K.A., Halyard, M. et al. Cancer Screening Experiences of Black Breast and Ovarian Cancer Patients and Family Members. J Community Health 48, 882–888 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-023-01233-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-023-01233-5