Abstract

The diagnosis of autism is often delivered solely to the parents, a practice that forces them to confront the dilemma of whether, when and how they should disclose it to the child. The present study seeks to probe deeper into the phenomenon of diagnosis disclosure and lead to a clearer understanding of the dilemmas parents? face. This article presents an analysis of a focus group and an online survey conducted with parents. The analysis produced a model that maps parents’ dilemmas regarding diagnosis disclosure to their child. The dilemmas, found to be complex and interconnected, concern the invisible nature of autism, the word autism and stigma, time motif, child’s environment, the act of disclosure itself, and the child’s personal narrative.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The vast majority of autism diagnoses are performed in childhood (Volkmar et al., 2009). For most parents, the diagnostic process culminates in them revealing to their child the diagnosis of autism (Smith et al., 2018). In many cases, the parents go through a long process of gradually internalizing and coming to terms with their child’s diagnosis. Thus, the parents’ experience is a complex and ongoing one (Crane et al., 2019). The question of disclosing the diagnosis to their child and to others in the child’s orbit, such as teachers, family, and friends is a particularly significant and complicated issue in parental co**.

Autism disclosure holds many implications for a person’s life and self-identity (Cadogan, 2015; Prentice, 2020). Whether the diagnosis was disclosed during childhood or later in life, autistic people will have to manage the diagnosis throughout their lives, as if it were an identity component (Riccio et al., 2021). However, most studies focus on the parents’ experience of co** with the diagnosis and childcare (Brogan & Knussen, 2003; Lai et al., 2015). Only a few studies have addressed the issue of parental disclosure of the autism diagnosis to the child (Crane et al., 2019; Smith et al.,2018) and the experience of self-disclosure and the effect of the discovery on the lives of autistic adults (Huws & Jones, 2008; Riccio et al., 2021).

Parents of autistic children have reported having difficulties in deciding whether revealing the diagnosis to the child would be in the child’s best interest, due to the concern that the child would experience the social stigma associated with the disclosure (Crane et al., 2019). The parents feared their child would reveal the diagnosis to other children who would use this information to isolate the child and treat him or her differently. Accordingly, studies examining the subject have found that autistic people report that diagnosis disclosure to them is delayed (DePape & Lindsay, 2016; Huws & Jones, 2008; Riccio et al., 2020; Smith et al., 2018).

This article presents the first part of a two-part study seeking to analyze the issue of autism disclosure delay and to offer an in-depth understanding of the co** strategies of both parents and autistic persons.

Due to the study’s broad scope, this paper will focus solely on the perspective of parents regarding the diagnosis disclosure to their child. We will dedicate a separate paper to the perspectives of autistic people regarding disclosure. However, this paper does include a glimpse of their views because the voices of autistic people are critical in understanding the issue - it would be inappropriate to address it without including such views, or, as the disability rights slogan states, “nothing about us without us.”

To Tell or Not to Tell?

Unlike many other disabilities (Down Syndrome, Cerebral Palsy, and more), autism in many cases is invisible, such that autistic children’s external appearance will not necessarily lead to labeling. Because autism is a highly stigmatized diagnosis associated with social marginalization and exclusion (O’Connor et al., 2020), the option of hiding the diagnosis from the child and their surroundings and kee** it a secret from the child (Davidson & Henderson, 2010) might be tempting. Therefore, parents face a dilemma regarding whether to tell the children about their diagnosis, accompanied by the question of who in their circle should be given this information, how and when. This dilemma is rooted in social norms and attitudes, parents’ personal perceptions, feelings and beliefs, and the anticipation of future outcomes and consequences of diagnosis disclosure.

Parental conduct is influenced by their social, cultural, and economic backgrounds and by the social stigma surrounding autism and its internalization by parents. The internalization of the stigma and the aspiration for a “normal” child make the question of diagnosis disclosure a more complicated one (Almog et al., 2019).

Around the world, stigma harms the well-being of autistic people and their families. It increases self-doubt and reduces opportunities for social support, psychotherapy, employment, and freedom of opportunity (e.g., Grinker & Cho, 2013; Dehnavi et al., 2011). Many studies focus on “affiliate stigma,” the sense of stigma experienced by parents of children with autism (Mak & Kwok, 2010). Parents of autistic children face various stigma-related feelings and generally try to maintain a life that will appear as normal as possible, especially within the context of what is known as the ״race for the perfect baby” (Ish-Am, 2020). However, in a society in which stigma is prevalent, parents’ failure to disclose the diagnosis prevents the child from acquiring the ability to cope with social judgment (Davidson & Henderson, 2010) and to practice self-advocacy skills (Duek-Huri, 2014).

The few studies that have examined parents’ attitudes toward autism disclosure to their children highlight a tendency to delay informing them (Smith et al., 2018). This reluctance is linked to the fear that the child will not understand the meaning of the diagnosis or will experience the social stigma commonly directed at autistic children. However, parents do recognize the importance of disclosing the diagnosis, for example, in increasing self-awareness of strengths and difficulties as well as the ability to self-advocate (Smith et al., 2018). A recent survey in the United Kingdom (Crane et al., 2019) examined parents’ experiences regarding diagnosis disclosure and found that most parents (67.9%) chose to disclose the diagnosis to their child and that, out of the parents who did not tell, most planned to do so at some point. The most common reason for not disclosing the diagnosis was the belief that the child could not understand its meaning. The parents also claimed that they would do so as soon as they believed their child could understand the diagnosis. The few parents who decided never to disclose the diagnosis argued that it is irrelevant if the child does not in fact face difficulties, adding that they, the parents, lacked professional support and guidance that could help them ensure the disclosure was conducted in the best way possible for the child (Crane et al., 2019).

Another significant challenge mentioned was co** with the stigma the child could face after disclosure. Many parents describe a fear of labeling and of a stigmatized experience that disclosure could entail, for example, a fear of social exclusion of their child by their peers. Yet many parents recognize the importance of sharing the diagnosis with their child from an early age to enable gradual mediated exposure; attribution of a neutral, balanced, or even positive value to the diagnosis; cultivation of self-advocacy skills; and subsequently, the facilitation of the formation of a positive disability identity. Moreover, concealment might instill in the child the feeling that “something is wrong with them, and it is so wrong that it should be hidden from the other children. . so wrong that it is forbidden to talk about it” (an excerpt from the testimony of a “covert”Footnote 1 personal tutor in Almog et al., 2019, pp. 47–48).

The findings regarding autistic people’s responses to their diagnoses are consistent with findings from studies concerning parents (DePape & Lindsay, 2014) and from findings of studies that focused on other disabilities (e.g., Bellin et al., 2007; Connors & Stalker 2003). This includes a process of mourning upon receiving the diagnosis, and struggling to accept the diagnosis, followed by understanding, acceptance, and identity formation.

Regarding how the diagnosis disclosure affects the child’s identity, Riccio et al., (2021) found that autistic teenagers whose parents had told them about their diagnosis included strengths in their own definitions of autism and defined autism as a neutral difference rather than a disorder or abnormality. In addition, receiving an autism diagnosis at a younger age is associated with heightened well-being and quality of life (Oredipe et al., 2022). Hence, parents play a critical role in the sha** of the child’s identity and future.

Furthermore, the understanding is that autistic children live with a horizontal identity (Solomon, 2012), differing from most of their family members, and therefore it is necessary to create processes that will enable them to become familiar with their identity in positive and beneficial ways.

This article presents the first part of an innovative study conducted in Israel and focuses on parents’ dilemmas regarding the disclosure of the diagnosis to the child.

The rationale of the entire study relies on a premise that a deep understanding of parental co**, along with a comprehensive understanding of the co** mechanisms of autistic children and young adults, might help develop intervention tools for parents and professionals that will increase the quality of life of children and young adults.

Research Objectives

The objectives of the study are both theoretical and practical. The research aims to map the dilemmas of parents of autistic children in Israel regarding the disclosure of the diagnosis to their child.

Methodology and research design

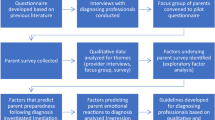

This research uses a grounded theory approach (Glaser & Strauss, 1967) that encourages researchers to develop an integrated set of theoretical concepts from their empirical materials. In grounded theory, the researcher creates a theory according to the data collected in the field, examines them, and verifies them again with the researched reality. The current research design uses this structural outline: focus group > data analysis > survey > member check > data analysis, and so on.

In addition, the methodology adopts the principles of the emancipatory research paradigm, an approach that enables the production of accessible and valuable knowledge about structures that create and preserve barriers encountered by many people with disabilities (Barnes, 2003; Oliver, 1992). In this study, the premise was that hiding the diagnosis from the child creates a barrier to self-development. The role of liberating research is to change the face of society in order to enable the full and equal and participation of people with disabilities (Welmsley, 2016) and to create an impact on the lives of people with disabilities and their families.

There has been limited research on parents’ dilemmas regarding diagnosis disclose to their child; therefore, the group of parents who have not yet told their children about the diagnosis and are debating how to do so were selected for this study. This group of parents face a fundamental dilemma and could benefit from participating in the parent workshops.

Research design

The parents’ workshops presented in this paper, conducted in cooperation with the Family Center of ALUTFootnote 2 (parent workshop 1 + 2), which disseminated the request to parents, handled both groups’ registration, and helped counsel the first group.

One of the principles of the emancipatory paradigm is the adoption of a partisan research approach and the denial of the objectivity and neutrality of the researcher. The researchers are not only experts in the field of content, but also put their skills to the benefit of people with disabilities and their families (Oliver, 1992). These principles, which shaped the choice to operate parents group meetings in a workshop format, are presented below:

-

1.

Running a workshop on a subject that so many parents are interested in allowed us not only to capture parents’ dilemmas, but also to give them an opportunity to have a group discussion on the subject. In the feedback provided by the parents after the meetings, they stated that they would recommend that more parents go through a similar workshop, which again emphasizes the value of attending for the parents participating in the study. Sharing experiences is empowering for the participants (Vernon, 1997).

-

2.

Throughout both parent workshops, the facilitators emphasized that the children should be informed of their diagnosis and have it explained to them, based on the understanding that familiarity with one’s autistic identity is important both in the present and in the future (Oredipe et al., 2022). At the same time, and in light of the fact that many parents expected to receive more practical solutions or answers, the team emphasized that disclosing the diagnosis to the child is an individual process, adjusted to age, ability, and other personal and family characteristics, and that it is recommended that parents receive guidance throughout the process because there is no “single recipe” for all families and children (Crane et al., 2020).

-

3.

The workshop also reflected the perception of neurological diversity: we emphasized personal and family uniqueness, the balance to be struck between difficulties and strengths, and the understanding that biological diversity is essential to human identity (Baron-Cohen, 2017).

-

4.

Another principle applied in the study is “nothing about us without us,“ the slogan associated with the struggle for the rights of people with disabilities, which emphasizes the importance of the participation of people with disabilities in every decision concerning them. Emancipatory methodology extends this slogan to “no longer researching about us without us” (Johnson, 2009), thus emphasizing the place of people with disabilities in creating knowledge about them. The design was enhanced in the parents’ encounter by having an autistic adult participate in the first group and the fourth author in the second group, providing parents with a firsthand encounter of an autistic adult and offering a glimpse of what the future might hold for their children. The participation of two autistic adults in both focus groups was noted by the parents as significantly contributing to the conversation. A majority of the parents noted that it was their first encounter with an autistic adult.

Settings for data collection

Parent workshop 1 - a two-meeting focus group.

The two meetings were facilitated by the first and second author with a social worker from ALUT. Both meetings lasted approximately two hours and were fully recorded and transcribed.

The first meeting was conducted as an open conversation in which parents were asked to share their thoughts and dilemmas regarding the subject of diagnosis disclosure to the child. In the second meeting, the same parents were joined by the mother of an 18-year-old with autism and Jonathan, a 28-year-old “diagnosed on the autism spectrum.”Footnote 3 Both shared their personal experiences. In addition, the parents received feedback survey a month after the second workshop had occurred. The feedback related to the present status of the parents vis-à-vis the dilemma (following the workshop: did they disclose the diagnosis to the child or begin the process?) as well as the workshop itself. All parents agreed that they would recommend that other parents participate in such a workshop.

Although the purpose of the focus group was not to assist parents directly in the process of diagnosis disclosure, but only to stimulate discussion on the subject and offer some insights, between the two meetings one parent chose to disclose the diagnosis to their child.

Parent workshop 2 – ZOOM meeting discussion and Survey.

This group was led via Zoom during the COVID-19 pandemic, with the participation of around 200 parents of autistic children from across the country. Grounded theory is a data analysis approach in which the researcher creates a theory according to the data collected in the field, examines it, and verifies it again with the data collected during the member check phase. Thus, the purpose of this workshop was to validate and to reanalyze the purposed model according to parents’ responses and feedback and to collect additional questions and dilemmas.

The group was facilitated by the article’s four authors and lasted two hours. During the first hour, the authors presented the findings of the first workshop – a five-stage model on the way to diagnosis disclosure, along with important aspects for sharing the diagnosis with the child.

Before each dilemma was presented (each stage of the model), a question or two were asked through Mentimeter, an interactive presentation software, for a limited amount of time, with 100 parents answering each question. Appendix 1 presents the questions and the dilemmas.

During the second hour, the parents expressed their opinions and asked questions, orally and via the chat feature, about how to disclose the diagnosis to the child. The data that emerged from that focus group contains a group transcription, the chat, and parents’ responses to the questions presented using Mentimeter.

Recruitment Methods and related issues

The Family Center of ALUT disseminated the request to parents and handled both groups’ registration. The invitation to participate in the workshop included a short description of the workshop’s goals, including deliberation on whether to tell their autistic child about their autism diagnosis and how and when to do so, along with technical details regarding dates and how to enroll. Both parents’ meetings were fully booked within a few hours. Since so many parents were interested in joining the Zoom meeting, we allowed 200 to participate, even though we knew we would not be able to collect answers from all the participants.

Participants included only parents who chose to participate in the workshops (self-selection), meaning they were already aware of the diagnosis disclosure dilemma and were able to engage in it with parents and professionals. Other parents, who have not participated in the workshops, may experience more acute shame or more significant conflicts regarding the disclosure of the diagnosis and therefore it is difficult to generalize the findings of the present study to apply to them as well.

Participants

First parent workshop – focus group

19 parents of autistic boys: 10 women and nine men, consisting of seven couples, three mothers, and two fathers. All the parents described their individual children as high-functioning, with an average age of 10. The average age of diagnosis was 3.5 years, which means that the dilemma of disclosing their diagnosis had already been part of their lives for an extended period. The exception was two couples; each had a child who had been diagnosed in the year prior to the workshop. Five of the children studied in special education frameworks (kindergarten, special education class), seven studied in inclusive education frameworks (of these, one with a personal tutor/assistant and three with a “covert” tutor/assistant). None of the parents who attended the workshop had yet told their children about the diagnosis.

Second parent workshop – Zoom meeting

No data were collected regarding these parents, just the age of the child (average = 9.5 years, range 3–30) and the fact that most (80%) had not yet told their children about the diagnosis and thought (98%) that ultimately they would need to.

Data analysis process

The data were analyzed based on grounded theory as outlined in the methodology of Glaser & Strauss (1967) and Strauss & Corbin (1990). Data from the first focus group were analyzed and set into five themes; each theme representing a unique component of the autism disclosure dilemma. The analysis process of the data included the following stages:

-

1.

Open coding - separating and sorting data segments from the first workshop and combining them in a new and different way. The open coding process is done by comparing the different parts of the data to find similarities, differences, and connections between them. The first author created the initial categories and gave them names; at the end of this phase we had 15 initial categories.

-

2.

Axial coding - The second level coding procedure involves recognizing relationships between categories. This stage is characterized by map** and recognizing main categories and subcategories and exploring the relationships between them (Creswell, 2008). During this stage the research divided the categories into five new themes representing the parents’ dilemmas.

.

-

3.

Selective coding - During this stage the theory is being developed. A story that connects the categories is constructed. It has already been established that grounded theory categories are related to one another (Strauss & Corbin, 1990), and that it was difficult to split the data into themes, as they seldom appear separately and all of them interact with one another.

-

4.

Grounded theory is constructed through a systematic process of repeatedly going into the field to collect an abundance of data until a meaningful and rich theory has been constructed (Shkedi, 2003). At this stage we built the first model to be presented to parents at the Zoom meeting. We designed the Zoom survey according to the five dilemmas found until that stage (see Appendix 1).

-

5.

Synthesizing the findings from the Zoom survey and discussion and focus groups - after the Zoom meeting, the survey findings were added to each theme. The transcription was read carefully and specially investigated quotes of parents of girls who didn’t attend the first workshop. Minor changes were made to the model and several components were redfined as will be presented in the discussion.

-

6.

Creating the theoretical framework / constructing the theory - conditional matrix.

The theory that emerged from the data provided an overview of prominent dilemmas that parents encounter through the process of deciding whether and how to disclose the diagnosis to their child.

Scientific rigor concerns

Credibility relates to the question of the extent to which the researcher can discover and describe the truth of the participants. In the current study, credibility was examined in several.

ways:

-

1.

Triangulation - a ‘within-method’ triangulation (Denzin, 1978) which uses multiple techniques within a given method to collect and interpret data. ‘Within-method’ triangulation involves cross-checking for internal consistency and was utilized in the current study by conducting two workshops, and repeating the same questions in different ways. An external validation by the participants was made in order to raise the credibility of the study. This process of ‘member-checking’ (Creswell, 1998; Lincoln & Guba, 1985) involves the researcher allowing participants to verify and clarify the researcher’s interpretation of the story.

-

2.

Writing the final report as ‘thick description’ (Geertz, 1973) - a multitude of details that allow the production of meanings and understanding phenomena. The research includes information about context, appropriate quotes, and detailed discussion of concepts.

-

3.

Reflection and self-criticism by the research team - during the analysis, previous assumptions, expectations and values were examined repeatedly. Since the team includes both professionals who work with parents and families and an autistic co-researcher, reflections of personal and professional biases were important to determine their potential influence on the research process.

Ethics

The study received the approval of the Ono Academic College’s Ethics Committee. During the recruitment phase, expectations were coordinated with the parents who participated in the first focus group. This was done by the director of the ALUT Family Center. It was emphasized that the purpose of the focus group was to investigate and discuss the issue but not to provide practical solutions. The parents who attended the first focus group signed an informed consent form and received an explanation that their personal information would remain confidential.

Parents in the second Zoom workshop were informed that the meeting was part of a study and received an explanation that their responses to the Mentimeter questionnaire, as well as the discussion, would be recorded anonymously and confidentially.

There was no conflict of interest in the collaboration between researchers from Ono Academic College and the ALUT Family Center. The interests of the parents and their autistic children were given top priority.

Findings

The findings of the qualitative analysis of the first focus group were combined with the findings from the second Zoom workshop. We discovered five interrelated themes and seven subthemes concerning parental dilemmas with diagnosis disclosure: (1) Autism In/Visibility and the Un/Known (2) The word autism and the stigma (subthemes: the word “autism”, stigma – Autism as an ongoing information-delivering and attitude-changing campaign) (3) The time motif - too early versus too late (subthemes: too early - fear of lack of maturity and the child’s difficulty of understanding the meaning of the diagnosis / fear of secondary gain, too late - fear of regression in behavior). (4) Those who already know and those who do not. (5) The why and how questions (subthemes: why should we tell? how should we tell? and what do we do afterwards?). The dilemmas are interconnected in a spiral manner. Each theme includes promoting factors that could help the parents disclose the diagnosis to the child and hindering factors that would caution against doing so. The promoting and hindering factors related to the parents’ dilemmas delineating the complexity of disclosing the autism diagnosis to their child. The findings are presented in a model that represents five themes (Fig. 1).

Figure 1

Figure 1 presents the model of the parents’ dilemmas regarding diagnosis disclosure to the child. In each dilemma, some factors delay disclosure of the diagnosis to the child, whereas some promote it. This is evidence of the complexity rising from the inner struggle and the debate around this issue. The complexity of the disclosure increases even more, as the parents have to cope with a continuing stigma involving approaches and attitudes toward autism. The struggle with social stigma and internalized stigma accompanies parents through the child’s lifetime, especially at the various times that disclosure of the diagnosis is being considered. These factors make exposing the diagnosis to the child a complex task, both emotionally and practically. The dilemma itself is not a “once-and-for-all” decision; rather, it is more typically a recurring or a continual phenomenon. The model is not linear, and parents might struggle with issues in a different order. When the parents reach the phase of disclosure and share the diagnosis with their child, they start a process of passing the torch over to the child – a step presented in the figure as a yellow flag at the end of a steep path. By doing so parents relinquish responsibilities, practice, and knowledge about autism to the child, modeling and encouraging their child to embrace self-advocacy. From that moment on, their child will have to cope with the stigma, and choose repeatedly whether they want to share the diagnosis with others or conceal it from them. The parents will be there to offer guidance and support. Each of the five themes that emerged are described below and their interconnections are discussed.

First Dilemma: Autism In/Visibility and the Un/Known

At the center of this dilemma stands a gap between an autistic child’s “ordinary” appearance and the child’s distinctive functioning and behavior, which differs from that of their peers. This gap raises questions and confusion, both in the child’s circles (school staff, friends, family) and among the children themselves. Parents repeatedly assert that their child’s diagnosis is not visible, and therefore can’t be noticed; for example, they said that the child is “highly functioning and that they (other people) can’t see it in him.” Nevertheless, in both focus groups, parents did refer to visibility,appearance and knowing about the diagnosis. In other words, they admitted that it is indeed possible to identify that their child is autistic, as in statements such as “the children are either with a personal tutor or going to a special education class; everybody knows,” or “their behavior isn’t normative.”

The parents of autistic children understand very well that “it cannot be concealed,” as the father of a 12-year-old said, “People around us... we’re lying to ourselves if we think that they don’t see or can’t put their finger on it exactly and judge.” The father of a six-year-old went even further: “To say that others don’t know is to live in denial.” The factor hindering diagnosis disclosure in this dilemma is autism’s lack of visibility: “if it isn’t seen, then we don’t have to speak about it.” The factor promoting diagnosis disclosure in this dilemma is the understanding that autism cannot be camouflaged and concealed indefinitely. Although it is “unseen,” distinctive behaviors and noticeable gaps emerge in social encounters with the child, which turn the disability from invisible to visible.

In most cases, several years had passed since the diagnosis was made. Thus, many parents needed to explain to their child the differences between them and other children, even before disclosing the diagnosis. However, most of the parents consciously refrained from using terms such as autistic or autism. They preferred to explain to their children that the differences stem from other factors, saying things such as: “He’s red-headed, so when they ask him, he’s red-headed and that’s connected to his character,” or “he knows that he’s special; he doesn’t know that he’s on the spectrum,” or “she knows that she has a very special attention deficit disorder.” Other parents used terms such as “communication disabilities,” “communication problems,” or “Asperger’s,” which they perceive as more neutral.

In the second parent workshop, two questions were presented to the parents regarding this dilemma. The first was: “How noticeable is your child’s autism?” The responses were on an axis between one (one cannot guess) and five (one cannot miss it). The value of three was defined as “visible/not visible.” Sixty-six percent of the parents rated their child’s autism visibility as one or two (one cannot tell it from the way they look), 28% gave the value of three (visible/not visible), and only 6% rated their child’s appearance at four or five (the autism is visible). Responses to the second question, “Do you think that your child knows about their diagnosis?” were as follows: 60% thought that their child did not know about the diagnosis, 18% thought that the child knew about the diagnosis, and 22% did not know whether or not they did. These responses indicate that most parents tend to see their child’s autism as invisible and that most of them believe their child is unaware of their diagnosis.

Over the years, and during an autistic child’s development, parents move on the axis between visible and non-visible. The act of disclosing the diagnosis, in fact, seals a transition toward visible for the parents, as even if the child “doesn’t look autistic,” their autism is then out in the open. After diagnosis disclosure, children themselves can tell others, meaning that the diagnosis could potentially become known to all. This moment in the child’s life is a cause of concern for the parents, especially because those around them don’t always fully understand the word and the diagnosis. Parents expressed concern over a negative branding stemming from a lack of awareness of the diagnosis and the stigma entailed by the term autism, which is the subject discussed in the following theme.

Exploring this first dilemma reveals that autism’s invisibility and parents’ belief that their child is unaware of their autism serve as hindering factors, which prevent parents from sharing the diagnosis with their autistic child or cause a delay in diagnosis disclosure. Conversely, visibility of autism in their child’s appearance or functioning and the belief that their child knows that they are different but doesn’t know about their autism serve as promoting factors that encourage parents to share the diagnosis with their child.

Second dilemma: The word autism and the stigma

This dilemma links two interrelated components - the word “autism” itself and the branding and stigma the diagnosis often involves.

The word “autism”

The difficulty experienced by parents vis-a-vis the term autism was seen in their reluctance to use the term and say the word. Many parents discussed specifically their dissatisfaction of the unification of various diagnoses under one definition in the DSM-5. Some parents emphasized that their child is high-functioning, whereas others used the term Asperger – a definition that no longer exists in DSM-5 – thereby expressing reservations regarding the changes that have occurred in the formal definition of ASD in the DSM-5. As one father explained, “I think that the moment autism became a word, autism or spectrum included all of the extremes in the same term, so it’s also low-functioning autism, which I think is what people see when they hear [the word] autism.” Some parents said that they were considering the use of the term Asperger as a solution, “as it is accompanied by more positive connotations in addition to the negative ones.” Only a few parents said that the word autism is used at home, but even they don’t use it in relation to the child “because we haven’t yet found the way to communicate it all to him.”

Clearly, if the parents do not use the word autism at all, or even if they use it but not in relation to their children themselves, then the fear of the stigma entailed by this word and the lack of understanding of the diagnosis constitute a crucial factor that hinders parents from disclosing the diagnosis to the child.

Another issue that parents discussed is the negative context of the word “autistic” in Israeli discourse and its frequent use as a curse or an insult to describe someone who is “emotionally disconnected.” Parents discussed the genuine fear that their child will be exposed to the word when used as an insult, internalizing its derogatory meanings, or will have to cope with it without prior preparation. However, some parents noted that, because the word is prevalent as an insult, their motivation to disclose the diagnosis to their child had increased so that they [children themselves] would become familiar with it in a positive context before encountering it in a negative one. This means that the fear of the stigma and the word may also serve as a promoting factor in disclosing the diagnosis to the child.

In response to the question of whether the child is familiar with the word autism presented in the second workshop, 48% of the parents answered that their child knows the word, 22% answered that their child may know it, and 30% answered that the child does not. This finding, together with the former, corresponds with the conflicted parents’ tendency to avoid using the term autism explicitly on the one hand and on the other hand to worry that their child would get acquainted with it negatively and uncontrollably. Moreover, this finding relates to the significant fear of unmediated negative disclosure of the diagnosis to their child by a third party. Because even if parents refrain from using the term autism in the presence of their child to protect them from the stigma, it is in everyday use, and the child might encounter it in a pejorative way.

Stigma - autism as an ongoing information-delivering and attitude-changing campaign

Parents are aware of the stigma, as they have experienced co** with it firsthand, both when receiving the news of the diagnosis and frequently when sharing it with others. In addition, parents have shared their own difficulties in co** with acceptance of the diagnosis. For example, one mother said: “[When] I received the diagnosis, it was very hard for me. And I asked myself, how will he receive it according to his own self-definition when he has to carry such a label?” From such assertions, we can learn that parents internalize and preserve a social attitude that autism is a tragedy, and they assume that their child’s worldview toward their own autism is a tragic one as well.

Due to the prevailing public ignorance about autism around the world, Israel included, parents have an ongoing and complex task of providing information, explaining, and advocating for their children. During the conversation in the first focus group, parents claimed that the definition of other disabilities, such as hearing or visual impairments, is much clearer and more comprehensible. However, even when they tried to explain explicitly what autism is, they found that “people around us do not know what to do with it; that’s the problem,” as one mother said. Though most of the parents in the groups debated and had excruciating doubts when dealing with the dilemma of whether to share the diagnosis with their child and how, one of them presented a consolidated and positive position on the subject: “Running away from the word autism is simply like living in the closet, concealing and denying.” He noted the responsibility of autistic children families to educate their communities to be more knowledgeable and to be more inclusive and tolerant, recognizing that it is a long-term process. His approach stood alone in contradiction to the positions expressed by the rest of the parents in the first focus group, which maintained that the task of “educating the world” is complex and exhausting. Furthermore, disclosure of the diagnosis to their children will transfer the responsibility for the information campaign and advocacy to the children themselves. In their desire to protect their children, parents struggle about the right timing for the disclosure. This subject will be discussed in the following dilemma.

Examination of the second dilemma discovered several hindering factors, such as the negative connotation attached to the term autism, public ignorance and the stereotypes regarding autistic people, the social stigma and self-stigma, the aggregation of various diagnoses under one title in the DSM-5, non-acceptance of the diagnosis, and the hope that it might disappear or be “cured” one day. Simultaneously, promoting factors emerged, such as the obligation to educate society about autism, the duty to correct stereotyped perceptions and change the stigma for their child, and most prominently, the fear of unmediated negative disclosure.

Third dilemma: The time motif - too early versus too late

A central dilemma connected to the diagnosis disclosure dilemma is the question of timing - when is it the right time to tell the child about the diagnosis and what might be the practical implications for disclosing it to the child at various ages? This issue had two opposing motivations. On the one hand, parents fear that disclosure at too young an age might be premature and lead to it not being understood, whereas on the other hand, waiting for a later age might lead to an uncontrolled disclosure of the diagnosis (as presented in the second dilemma); or to entering adolescence (which is in any case difficult) or even adulthood unaware of their own diagnosis. This dilemma comprises two subcategories – “too early” relates to fear of a lack of maturity and the child’s difficulty in understanding the meaning of the diagnosis and fear of secondary gain, and “too late” refers to fear of regression in behavior during adolescence.

Too Early - Fear of lack of maturity and the child’s difficulty in understanding the meaning of the diagnosis

Parents in the focus groups expressed concern that the child’s communication skills would make it difficult for them to understand the diagnosis and its implications. Hence, although some of the children had already shown interest in their diagnosis and had asked about it, their parents remained worried about “whether the child knows but doesn’t really understand exactly.” Parents’ assertions often testified to a doubt about whether the child could fully comprehend the diagnosis, such as “we have to take into account what they can absorb.” In other words, what must be considered are the unique abilities and difficulties of each child, as shown in the words of one mother, who emphasized that the process of disclosure requires individual work adapted to the child’s characteristics. She stated: “There’s a problem how to open [the subject] because every autistic person is different. Really. Wow, just completely different.” This aspect emphasizes just how much the parents need personal assistance and support to decide on the right timing and on how to disclose the diagnosis to the child.

Too early - Fear of secondary gain

Another issue parents expressed regarding the issue of diagnosis disclosure is the fear that the child will exploit the situation, referring to what is known in the literature as “secondary gain.” This pertains to the fear that awareness of the diagnosis will lead the child to withdrawal and avoidance, or the exacerbation of these patterns, playing a ‘sick role.’ To state it simply, parents expressed the wish that their child “will not try to make things easier for themselves after disclosure,” or as described by one mother: “So he’ll say, ‘Okay, I’m not good at social relationships, so I can put that aside,’ and bye-bye to his social life.” Parents see secondary gain as affected by the maturity of the child and his emotional readiness to deal with the diagnosis disclosure. This fear of autistic children’s parents that they will seek secondary benefits was found in previous studies as well, where parents expressed the fear that their children would use the diagnosis to excuse their behavior, especially negative behavior (Ruiz Calzada et al., 2012; Linton, 2014).

Too late - Fear of regression in behavior

Adolescence is a difficult age for any teenager, and it is even more complex for autistic adolescents, who often face negative social experiences, such as rejection, bullying, and social exclusion by their peer group (Cresswell et al., 2019; Locke et al., 2010). Hence, delaying disclosure of the diagnosis to this age group might increase the risk of regression, or the risk of potential mental health issues. It is therefore not surprising that one of the parents’ biggest fears is that diagnosis disclosure will lead to regression of the child’s behavior. One of the mothers shared her fear, saying, “Many times, when we began talking about the subject. . and that word. . he got into a very dark mood, and I don’t know what to do with it.”

In the second parent workshop, we asked the parents to choose which variables need to be taken into account in relation to diagnosis disclosure. It seems the most significant factors for the parents are those concerning the child, including the child’s maturity (92%), functioning level (52%), and age (42%). In contrast, according to the parents, factors concerning social characteristics, such as the community (28%) or school environment (27%), are less relevant to the issue of diagnosis disclosure.

To sum up this dilemma: it seems that, on the one hand, parents are afraid to disclose the diagnosis too early, as the child is not sufficiently mature and/or the child might exploit the diagnosis; these serve as hindering factors, hindering parents from diagnosis disclosure. On the other hand, parents are also afraid to drag the diagnosis disclosure into the child’s tempestuous adolescence, thereby leading to regression. Thus, this serves as a promoting factor, encouraging parents to disclose the diagnosis to their child.

Fourth dilemma – Those who already know and those who do not

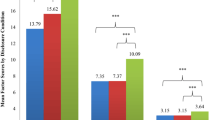

A crucial part of the parents’ discourse about diagnosis disclosure related to the immediate family, especially the autistic child’s siblings. The discussion focused on “those who already know” and “those who don’t yet know,” hurdles, fears, and implications. Those who already know might be a promoting factor in disclosing the diagnosis to the child. However, siblings, “ones who do not yet know,” become an additional reason for concealing the diagnosis. It has to be decided how and when to share the diagnosis with family and others, beyond the issue of disclosing to the autistic children themselves. Many factors are considered in parents’ decisions about diagnosis disclosure to the rest of the family, to others, and to the child. As we mentioned previously, two of the most crucial factors are the child’s visible or invisible appearance and the ability to manage the stigma. Parents often consider who might be able to discern the diagnosis; who can understand it and who cannot; and who needs to know about it and who does not. It seems that, from the moment the parents receive the diagnosis, the question of sharing it with others arises. We asked the parents in the Zoom meeting: who already knows about the diagnosis? The responses appear in Fig. 2.

Figure 2

Figure 2 presents the answers of participants in the second workshop to the question – “Whom have you shared the diagnosis with?” Although sharing the diagnosis with personnel in the educational framework system is the most prevalent (89%), as it is necessary for arranging the child’s rights and receiving special education services, sharing it with family (73%), friends (58%), workplace (56%), and extended family (52%) was done on a need-to-know basis to receive practical and emotional support.

In the first focus group, the parents mentioned how important it was to share the process of the diagnosis disclosure with the school educational team, not only to get their child the help they need and to be supported by the staff along the way, but also to be able to explain the correct terms of the diagnosis and their meaning and to be the child’s advocate. The educational team, too, has stereotyped approaches and attitudes toward autistic children; the team needs the mediation of the diagnosis, its manifestation in their pupil’s specific case, and its various implications.

Sharing the diagnosis with the siblings (39%) is much less prevalent. This is due to the tight connection between the diagnosis disclosure process and the issue of stigma management, as siblings usually tend to share whatever is occurring in their lives with children and others in their surroundings. To avoid uncontrolled exposure, parents often refrain from sharing the diagnosis with the child’s siblings. The least prevalent disclosure is sharing the diagnosis with autistic children themselves (19%).

One factor that promotes disclosure of the diagnosis to siblings stems from their future role as caregivers. The parents are likely troubled by the need to place the burden of looking after the autistic child in the future on their siblings, as described by a mother, “… He already understood that he’ll have to look after his brother later on, as he’ll still be here after we’ve passed away.” The acknowledgment that this is a multigenerational issue enters into the parents’ considerations concerning diagnosis disclosure to siblings.

Parents’ deliberations on sharing the diagnosis accelerated when siblings, both older and younger than the diagnosed child, begin to notice the autistic child’s differences. Siblings ask questions about these, for example: “Why does he go to that special activity?”Footnote 4 “Why does she have a caregiver?” and “Why does mom have books about autism at home?” The parents start to wonder what is the right way to explain and mediate the diagnosis to the sibling. We should note that, although the siblings are able to state explicitly what they see and feel, and express their questions and thoughts about their diagnosed sibling, in many cases the autistic siblings cannot express themselves in the same way, although they feel and experience that they are different from their peers and siblings in many ways.

Despite the difficulties involved in disclosing the diagnosis to the neurotypical siblings, some of the parents noted that a brother or sister might be the solution to the diagnosis disclosure, as stated by one such parent: “It [diagnosis disclosure] may arrive due to his brother, and it’ll somehow roll off from there. He (the autistic child) didn’t ask, and if he didn’t ask, then we apparently won’t say anything, but it may happen at a certain point, and that’s it.” In other words, it is possible that sharing the diagnosis with a sibling may in fact provide the means of making the disclosure to the autistic children themselves easier for parents, as they will hear it from their siblings.

Birth order influences disclosure. As opposed to families in which the autistic child is the eldest, in families where they are the youngest, older siblings were exposed to the diagnosis before the autistic child was, either deliberately or unintentionally. The parents’ experience, in this case, was a good one, as noted by one mother: “We don’t need to be afraid of it. Just the opposite, when we put the issue on the table… we’ll all be a better family.”

Even though some parents accepted that sharing the diagnosis with others can be beneficial, important, and a positive family experience, they did not extend that notion to include their autistic child. That is, they did not assume that, just as disclosing the diagnosis with the siblings was a liberating experience for them, so too might it also be a liberating experience for their autistic child.

To sum up the fourth dilemma, sharing the diagnosis with family members, especially siblings, stimulates both hindering and promoting factors for disclosing the diagnosis to the autistic child. A situation in which siblings and other family members do not yet know is in itself a hindering factor, as that creates another enormous hurdle to overcome, that is, the difficulties involved in disclosing and mediating the diagnosis to others. In addition, parents fear unwanted and uncontrolled distribution of the information. On the other hand, in families in which siblings and other family members already know, this situation serves as a promoting factor, as sometimes it is they who disclose the diagnosis to the autistic sibling. Moreover, sharing the diagnosis with others may be beneficial practically and emotionally and, in many cases, a necessity (for example in order to receive support at school or benefits from social security).

Another important promoting factor is the liberating and positive experience parents feel after sharing the diagnosis with siblings and other family members. Interestingly, even parents who have experienced this avoided the next step of including the autistic child in the liberating effects of diagnosis disclosure, the reason being that they were not sure their child’s experience would be as positive as their own. The autistic child’s experience is at the center of the fifth and final dilemma.

Fifth dilemma –The why and how questions

This dilemma concerns two subjects, namely, how and why the diagnosis should be disclosed. These two issues reveal the core of the diagnosis dilemma.

Why should we tell?

Parents who participated in the focus groups expressed a wide range of opinions concerning the need to tell their children about their diagnoses. Some parents wondered whether the lack of knowledge about the diagnosis bothered the autistic child at all. As stated by one parent in the first group: “It’s natural for him; he was born this way.” Some parents explained that this experience of being different is natural for their child, as they are not familiar with anything else, especially because many of the participants’ children had received individual or group therapy from a young age. Some parents believe that the subject doesn’t bother their child, as one mother stated, “he’s an easy-going child, and he didn’t ask. . he took it for granted.”

Alongside these perceptions, other parents claimed that, as time goes by, the child’s need to receive an explanation for their experience of being different increases. These parents noted that their children were starting to feel they are different, asking questions about the diagnosis and “touching upon” the word autism. As parents of a 13-year-old boy stated, “Maybe it’s time to tell him so that he knows what his situation is, as he knows that he’s different. But he doesn’t know precisely in what way he is.”

Some parents emphasize the importance of building a personal narrative for the child, as one mother said, “I don’t care about the people around him. . I want him to feel good about himself, that his life story will be whole. How do I create an accurate genuine positive story? It is not just, ‘you are autistic’ because you are not.” These final words, “because you are not” demonstrate two points. The first is how difficult it is for many parents to accept the term autistic (as described in the second dilemma), and second, overcoming stigma and stereotypes can be difficult; delivering the diagnosis to the child should be done in a cohesive and positive manner. The complexity emphasizes the spiral nature of the five dilemmas and how they interact with one another. The need to share the diagnosis with the child, due to the time that has elapsed and the questions arising about the children being different, and the need to build a complete and positive story for the children about themselves, were both found to be promoting motivations for disclosing the diagnosis to the autistic child.

In the second Zoom meeting, we asked the parents whether they thought their child should be told about the diagnosis, and 98% of the parents answered yes. This unequivocal finding, together with the finding that only 19% of them disclosed the diagnosis to their child, underscores just how much parents need help with the question of how best to disclose the diagnosis, since it is a delicate and complicated task.

How should we tell? And what do we do afterward?

Another issue that was broadly discussed by parents dealt with the inevitability of a stage in which the parents share the diagnosis with their child. Participants in both parent workshops claimed that they must prepare for it in advance, giving it much thought and preparing answers and explanations for possible questions. The parents raised many questions about the actual act of diagnosis disclosure and about how to do it properly. Some parents in the first workshop had consulted with professionals involved in the child’s care but had not reached the stage of actual disclosure. From their responses, it seemed they had not received the helpful answers and assistance from the professionals and did not always succeed in delivering the diagnosis. This was demonstrated by one mother’s statement: “And then he simply asked his therapist if he is a high-functioning autistic, as if he had diagnosed himself, so we’re debating with her for a long time already what to do, how.” This quote reveals two different points of view relating to the disclosure process. First, the perspective of the child, who is already aware of the diagnosis and seeks to validate it, and second, the perspectives of the parents and professionals, still debating the disclosure. Another mother said that her son had spent four years in therapy dealing with the disclosure process, thereby demonstrating the need to develop and improve existing interventions for this issue to provide parents with better tools and support tailored to their unique situation.

Many parents expressed the need to develop a set of intervention tools to help them carry out the process of disclosure. Such tools would take into account the specific nature of their child’s autism, abilities, disabilities and preferences, and would help the parents turn the complex and abstract notion of autism into an explainable and accessible one. Some of the parents suggested building a social story that would help them with the diagnosis disclosure. Others offered advice, thoughts, and ideas for co** with the process of disclosure. One such solution was to disclose the diagnosis gradually. Gradual disclosure is connected to the importance of the right timing and age (dealt with in the third dilemma), as noted by one of the fathers: “In any case, you don’t just go and say to your three-year-old, listen, you are autistic.”

Parents are also troubled by the stage following the disclosure of the diagnosis to the child, the stage when the child could share the diagnosis with others, especially with their classmates and friends. In both groups, parents discussed their impressions about a common practice in many schools whereby – after weeks or months following the disclosure of the diagnosis to the child – the children themselves disclose it to their classmates in a lecture or some other class activity. On the one hand, some parents said they were in favor of this practice, having heard that “it was very well accepted.” Some parents, on the other hand, disagreed. One mother stated, “I don’t understand this trend where they stand in front of the class … announcing ‘I’m autistic’ and then marking the task as done.” In the second meeting of the first focus group, the parents were exposed to Jonathan’s viewpoint. He had lectured to his classmates on the subject about a year after the diagnosis was disclosed to him. Jonathan claimed that “sadly, the lecture didn’t bring about the results I’d expected. Because although there were cases where I was treated well (after the lecture), it was really the exception, and I don’t think that the conversation changed anything.”

As Jonathan stated, a one-time event does not necessarily constitute a way of changing basic attitudes, and perhaps the use of this practice should be reconsidered, given its current prevalence.

In summary, in terms of the fifth dilemma, research data reveal several promoting factors: the finding that most parents believe that, as difficult as it is, the diagnosis should be revealed to their child; the possible liberating and positive effects of sharing the diagnosis with others; and the need to build a complete and positive narrative of self-identity for their child. However, at the same time, hindering factors appear, including the need for help, advice, and guidance from professionals throughout the process of diagnosis disclosure, followed by a call for a professional’s help in building an adapted or tailored plan for the child’s self-advocacy after disclosure.

Concluding discussion

Several studies have dealt in general with the subject of diagnosis disclosure and its implications for autistic children and their parents (Smith et al., 2018; Huws & Jones, 2008) found diagnosis disclosure delay as a main theme characterizing the perceptions of autism and the experience of autistic adolescents. Their analysis suggested that delay in disclosure may locate autism as an “absent presence” for part of the lives of autistic individuals. Possible reasons for a delay in autism disclosure includes the fear that the child will not understand the diagnosis or might find the label distressing (Camarena & Sarigiani, 2009; Huws & Jones, 2008).

The aim of the present research was to map parents’ dilemmas’ regarding diagnosis disclosure, to open it up for discussion, to reveal its complexity, understand its components, and to learn about the subject from parents’ perspective given the daily realities they face. The article offers a model map** parents’ dilemmas and outlining factors that hinder or promote disclosure.

The grounded theory revealed in the research presents five prominent dilemmas addressed intensively. First, the visibility of their child’s autism and parents’ estimation whether their child knows about their diagnosis, where visibility and estimated knowledge were found to be promoting factors and invisibility and the estimation that their child is unaware were found to be hindering factors. Second is the use of the term autism and the stigma, whereby unification of various diagnoses under one definition, social stigma, and internalized stigma serve as hindering factors, whereas the fear of uncontrolled and unmediated negative exposure to the diagnosis serves as a promoting factor. The third is the time motive, whereby considerations of maturity and the ability to understand, accompanied by the concern of possible secondary gain behaviors, serve as hindering factors, whereas fear of being too late, with the child entering adolescence along with the fear of regressive reactions, serve as promoting factors. The fourth motive entails who already knows and who does not, such as situations in which others and especially siblings know, together with a positive, liberating experience of disclosure, serve as promoting factors, whereas situations in which siblings and other family members still do not know, coupled with the difficulties and burden of disclosing the diagnosis to them, serve as hindering factors. The fifth and final motive includes why and how to tell the child, wherein the need for a professional’s help and a personal tailored plan serve as hindering factors, while an acknowledgement of the necessity to reveal the diagnosis to the child and help them build a cohesive and positive self-identity and acquire self-advocacy skills serve as promoting factors. The model is spiral, and the dilemmas are interconnected and inseparable.

Diagnosis disclosure is an ongoing and lengthy process. From the moment the parents receive the diagnosis, they have to disclose it to family members, friends, other relatives, and later on to broader circles such as educational, health and welfare services, and neighbors. They have to handle internalized and social stigma, to decide with whom, when, and how to share the diagnosis, to become informed and to inform other people, and to explain and to advocate for their child. They must share it with the child and therefore deliberate over when and how is best to do it. Hence, the mission of disclosing the diagnosis to the child is laden with many implications.

While disclosure demands that the parents accept the diagnosis, concealment enables them to partially deny and suppress it and to cope with it only partially. The act of disclosure requires an active endeavor, that is, to find the language and words appropriate for explaining and mediating the information to the child and his/her surroundings. Words and alternative explanations must be found for the child’s difference and the gap between them and their environment. Concealment, however, might be equated with doing nothing, although there is likely a great deal of emotional energy involved in it as well.

The reasons for disclosure are more often related to maturation, to the process of self-determination, and to providing tools for co** with reality and the environment. Conversely, the reasons for concealment are related to difficult feelings of shame, concern, and fear surrounding the stigma. Fear, it should be mentioned, arose around disclosure as well. It seems clear that a central motive for diagnosis disclosure is to help the child with self-understanding and to promote self-advocacy, as found in the study conducted by Riccio et al., (2020).

The Diagnosis Disclosure Dilemmas Model presented above can provide professionals with a better understanding of the process parents go through and suggest a structured and adapted response to parents’ dilemmas, questions and fears during the process of diagnosis disclosure to the child. We hope the model will enable parents and professionals to analyze together the hindering and promoting factors, to face the difficulties and embrace the opportunities during the diagnosis disclosure process, and to understand its importance for the child.

At the end of the first focus group, Jonathan stated the following, demonstrating the personal transition that the child or adolescent must undergo in the process of self-discovery after diagnosis disclosure has occurred:

In the first years, it was harder for me to accept the diagnosis, and now it’s easier. Today I am more accepting of who I am, accepting myself as I am, and accepting my life as it is. .. I don’t really think that it matters that I have this diagnosis; now I have to see how I live my life. .. and I have to succeed in living the best and happiest life with it.

Jonathan demonstrates the process the child undergoes after diagnosis disclosure, when they develop their identity and life narrative, especially the change of focus – from the desire to eradicate the diagnosis up to the point of acceptance. This process of forming a self-identity and narrative lies at the core of the second part of the research.

The study’s limitations and suggestions for follow-up studies

This article is based on a limited sample. The first group included 19 parents of autistic boys, the only ones in their immediate families to be diagnosed with autism. Hence, this study’s ability to examine the process of co** with diagnosis disclosure by girls is limited, as is the examination of the experience whereby more than one child in the family is diagnosed with autism.

We consider it crucial to expand the model developed in this study and to include parents of autistic girls (a study being conducted these days), parents of more than one autistic child, and parents from a range of multicultural groups (Arabs, ultra-Orthodox Jews). For these groups the meaning of stigma is extremely acute and therefore the issue of concealment or disclosure has far-reaching implications for family life and future (e.g., reducing siblings’ chances of getting married, social condemnation and more). We are currently continuing to hold parent workshops according to different characteristics (i.e. – parents of autistic girls, ultra-Orthodox parents etc.) in order to reanalyze and expand the model presented in this article.

Finally, the research is based only on parents’ views and experiences. As the issue of diagnosis disclosure has two perspectives, gathering a broader autistic view is crucial to its understanding. As we mentioned before, this is being done as another part of the study. That part aims to explain how diagnosis disclosure affects the development of autistic young adults’ individual and group identity and to conceptualize the point of view of autistic young adults regarding autism disclosure. We hope that these two studies will create an established body of knowledge based on the experiences of autistic people and their families and that it will assist professionals, parents, and autistic children in co** with the complex process of diagnosis discovery and disclosure.

Notes

In Israel, parents can choose whether the child’s personal tutor will serve as the class tutor, meaning that the rest of the class, and sometimes even the educational staff, don’t know that the tutor is there to assist a specific child (“covert” tutor / assistant). Parents often choose this option to avoid stigmatizing the child in school. In some cases, the children themselves don’t know that the tutor in the class is there to assist and support them.

ALUT -The Israeli Society for Children and Adults with Autism, one of the first parent NGOs in Israel.

Jonathan’s self-presentation appears in this article with his consent under his first name and in the wording that he chose.

For example – occupational therapy, social skills group etc.

References

Almog, N., Bar, N., & Barkai, S. (2019). Narratives of inclusion and exclusion: Families between the medical, social and affirmative models of disability. In: P. Shavit & O. Gilor (Eds.) To be a parent of a child with a disability – Family as an active agent for social change in community and society. (pp. 29–64). Ach Books (In Hebrew)

Bellin, M., Sawin, K., Roux, G., Buran, C., & Brei, T. (2007). The experience of adolescent women living with spina bifida Part I: Self-concept and family relationships. Rehabilitation Nursing, 32, 57–67. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2048-7940.2007.tb00153.x

Brogan, C. A., & Knussen, C. (2003). The disclosure of a diagnosis of an autistic spectrum disorder: Determinants of satisfaction in a sample of Scottish parents. Autism, 7(1), 31–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361303007001004

Cadogan, S. (2015). Parent Reported Impacts of their Disclosure of their Child’s ASD Diagnosis to their Children. (Master’s thesis, Graduate Studies) 114. https://doi.org/10.11575/PRISM/27257

Camarena, P. M., & Sarigiani, P. A. (2009). Postsecondary educational aspirations of high-functioning adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorders and their parents. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 24(2), 115–128

Connors, C., & Stalker, K. (2003). The views and experiences of disabled children and their siblings - A positive outlook. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers

Crane, L., Hearst, C., Ashworth, M., Davies, J., & Hill, E. (2020). Supporting newly identified or diagnosed autistic adults: An initial evaluation of an autistic-led programme. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 51, 892–905. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04486-4

Crane, L., Jones, L., Prosser, R., Taghrizi, M., & Pellicano, E. (2019). Parents’ views and experiences of talking about autism with their children. Autism. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361319836257

Cresswell, L., Hinch, R., & Cage, E. (2019). The experiences of peer relationships amongst autistic adolescents: A systematic review of the qualitative evidence. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 61(January), 45–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2019.01.003

Davidson, J., & Henderson, V. L. (2010). “Coming out” on the spectrum: Autism, identity and disclosure. Social and Cultural Geography, 11(2), 155–170. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649360903525240

Denzin, N. (1978). The research act: A theoretical introduction to sociological methods. New York: McGraw Hill, Inc.

DePape, A. M., & Lindsay, S. (2016). Lived experiences from the perspective of individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A qualitative meta-synthesis. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 31(1), 60–71. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088357615587504

Geertz, C. (1973). The interpretation of cultures. New York: Basic Books

Glaser, B., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory. Chicago, Il: Aldine

Huws, J. C., & Jones, R. S. P. (2008). Diagnosis, disclosure, and having autism: An interpretative phenomenological analysis of the perceptions of young people with autism. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 33(2), 99–107. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668250802010394

Johnson, K. (2009). No longer researching about us without us: A researcher’s reflection on rights and inclusive research in Ireland. British Journal of Learning Disabilities, 37(4), 250–256. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3156.2009.00579.x

Lai, W. W., Goh, T. J., Oei, T. P. S., & Sung, M. (2015). Co** and well-Being in parents of children with Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD). Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45(8), 2582–2593. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-015-2430-9

Linton, K. F. (2014). Clinical diagnoses exacerbate stigma and improve self-discovery according to people with autism. Social Work in Mental Health, 12(4), 330–342. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/15332985.2013.861383

Locke, J., Ishijima, E. H., Kasari, C., & London, N. (2010). Loneliness, friendship quality and the social networks of adolescents with high-functioning autism in an inclusive school setting. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 10(2), 74–81. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-3802.2010.01148

O’Connor, C., Burke, J., & Rooney, B. (2020). Diagnostic disclosure and social marginalisation of adults with ASD: Is there a relationship and what mediates it? Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50(9), 3367–3379. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-019-04239-y

Oredipe, T., Kofner, B., Riccio, A., Cage, E., Vincent, J., Kapp, S. K., Dwyer, P., & Gillespie-Lynch, K. (2022). Does learning you are autistic at a younger age lead to better adult outcomes? A participatory exploration of the perspectives of autistic university students. In Autism. https://doi.org/10.1177/13623613221086700

Prentice, J. (2020). Children and young people’s views and experiences of an autism diagnosis: what do we know ? GAP, 21(2), 52–65

Riccio, A., Kapp, S. K., Jordan, A., Dorelien, A. M., & Gillespie-Lynch, K. (2020). How is autistic identity in adolescence influenced by parental disclosure decisions and perceptions of autism? Autism. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361320958214

Riccio, A., Kapp, S. K., Jordan, A., Dorelien, A. M., & Gillespie-Lynch, K. (2021). How is autistic identity in adolescence influenced by parental disclosure decisions and perceptions of autism? Autism, 25(2), 374–388. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361320958214

Ruiz Calzada, L., Pistrang, N., & Mandy, W. P. (2012). High-functioning autism and Asperger’s disorder: utility and meaning for families. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42(2), 230–243. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-011-1238-5

Solomon, A. (2012). Far from the tree: Parents, children and the search for identity. York, N.: Scribner.

Shkedi, A. (2003). Words that try to know: Qualitative research - theory and practice. Tel Aviv : Ramot Publication. (in Hebrew)

Smith, I. C., Edelstein, J., Cox, B. E., & White, S. (2018). Parental disclosure of ASD diagnosis to the child: A systematic review. Evidence-Based Practice in Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 3, 105–198. https://doi.org/10.1080/23794925.2018.1435319

Strauss, A. L., & Corbin, J. (1990). Basics of qualitative research. Newbury Park. CA: Sage

Vernon, A. (1997). Reflexivity: The dilemmas of researching from the inside. In: Barnes, C. & Mercer, G. (Eds.). Doing disability research (pp.158–176). Leeds: The Disability Press.

Volkmar, F. R., State, M., & Klin, A. (2009). Autism and autism spectrum disorders: Diagnostic issues for the coming decade. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 50(1–2), 108–115. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.02010.x

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Compliance with Ethical Standards

The study received the approval of the Ono Academic College’s Ethics Committee. There was no conflict of interest in the collaboration between researchers from Ono Academic College and the ALUT Family Center. The interests of the parents and their autistic children were given top priority. The author received no funding for this research.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Apendix 1

Apendix 1

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Almog, N., Kassel, O., Levy, N. et al. Map** the Dilemmas Parents Face with Disclosing Autism Diagnosis to their Child. J Autism Dev Disord 53, 4060–4075 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-022-05711-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-022-05711-y