Abstract

When upstream suppliers are VAT-exempted, overclaiming by fictional invoices becomes easier. This paper examines the effect of the presumed input VAT deduction reform on VAT evasion among VAT-exempted transactions in China. In the reform, firms are required to claim the presumed input refund of VAT based on downstream sales volume instead of on purchasing cost recorded on self-issued purchased invoices. We find that the reform reduced firms’ VAT evasion since taxpayers have little incentive to use spurious invoices. Furthermore, the reform demonstrated more pronounced policy effects when taxpayers are low in tax-compliance and local economy contains a higher share of tax-noncompliant firms with poor accounting records. Results survive a battery of robustness checks as well as treatment effect heterogeneity. The presumed input VAT method would be a complementary tax enforcement tool to avoid VAT evasion in low tax capacity and high-informality settings under the context of credit-invoice VAT collection system.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

VAT has contributed roughly 35% to China’s total tax revenue in the past five years according to China Statistical Yearbooks.

At the initiation of PDR reforms studied in this paper, China's agricultural population was still as high as 47.43 percent of the total population.

While for trading firms, firms with the turnover exceeding 800,000 Chinese yuan is required to register as a general VAT taxpayer.

The classification has been changed since the “Business tax-to-VAT” reform which took place in 2013. After this reform, a firm with a turnover of over 5,000,000 Chinese yuan, no matter which industry it belongs to, is classified into the type of the general VAT taxpayer.

When firms are registered as small-scale VAT taxpayers, input credits cannot be claimed against tax liabilities. In all empirical regressions, small-scale VAT payers are excluded from the sample.

China’s tax invoice is composed of VAT special invoice and VAT general invoice. Buyers can only claim input VAT credits when they obtain VAT special invoices. Buyers are not authorized to claim input credit since they get VAT general invoice.

China’s tax authorities are composed to a head office, located in the capital Bei**g, and multiple regional office located throughout the country. With respect to regional tax offices, they are divided into the State Administration Tax (SATs) and Local Administration Tax (LATs). SATs are directly managed by the head office, and in charge of central tax and shared-tax collection (e.g., VAT, consumption tax). LATs are managed both by provincial governments and upper-level LATs. LATs mainly collect local tax.

The deduction rate set for VAT-exempted suppliers selling PAPs is 13%, which is the same with the VAT tax rate set for taxable suppliers selling PAPs. Therefore, buyers claim the same amount of input tax credits no matter suppliers’ taxable status with respect to given input costs.

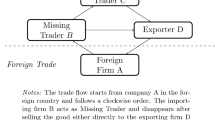

Under the second circumstance, tax collusion can be easily achieved between sellers and buyers. On the one hand, buyers do not require VAT invoices from taxable sellers, so sellers can hide sales revenue. On the other hand, buyers issue spurious purchase receipts to taxable sellers. Thus, buyers overreport input costs and get refunded. In the Appendix, we provide an example to show that fabricating purchase invoices is the main method to evade VAT in most PAPs transactions.

The APP sector refers to a horizontal set of manufacturing activities engaged exclusively in the production of agricultural and non-agricultural products from the processing of agricultural raw materials. The APM sector refers to all activities engaged in the flow of farm-produced goods, raw materials and derivatives from farms to ultimate customers, including firms like agriculture product distributors, wholesalers and retailers.

For APMs that buy PAPs directly for reselling, input credits are imputed as \(\sum\nolimits_{{i = 1}}^{n} {sales_{i} /(1 - wastagerate_{i} ) \times price_{i} \times 13\% /(1 + 13\% )}\). The wastage rate is the ratio between the amount of PAPs that have been wasted during reselling and total number of purchased PAPs. Because pilot industries in this study are mainly agriculture manufactures, we focus on the sales-based method as well as the cost-based method.

For firms that use a certain PAP as the input but produce multiple output products, tax authorities in charge should reasonably allocate the unit consumption rate for each output product.

The unit consumption rate needs to be adjusted since the production technology advances. The central tax head office allowed tax offices at provincial-level to redefine the consumption rate once it becomes improper. However, the unit consumption rate should stay unchanged at least for 36 months. For all pilot industries in this study, unit consumption rates remain the same during the whole sample period.

In Table14, we demonstrate the 1ist of the 18 pilot industries (four-digits) that are not given unit consumption ratios for main PAPs. Firms from these 18 industries have discretion to claim input credits with the cost-based method. Actually, buyers would also be discouraged from overreporting input credits by adopting the cost-based method, as they had to submit accounting records and financial documents to tax authorities under the new method. After examining submitted accounting records, tax authorities decided whether the cost ratio last year can be used to calculate PAPs input credits for current year. The strict checking-up process deters firms from exaggerating purchase costs. We examined the effect of PDR on reducing VAT evasion for the 18 industries. Results showed that the policy effects hold. Results can be referred in Table 21. For baseline empirical analysis, we exclude firms from these 18 industries.

The industry is classified according to China’s National Standard Industrial Classification of All Economic Activities in 2011 (NSIC, i.e., GB-T 4754–2011).

We illustrate the four percentage points windfall from changes in statutory deduction rates in Appendix Figure 5.

The NTSD covers a full range of sectors including agriculture, manufacturing, mining, building and service sectors. The ASIF contains information only on manufacturing and mining firms.

Stratification standards include total sales, industry and types of taxpayers.

The dependent variable may be a function of tax auditing, but main findings hold after tax auditing is taken into account. We offer several solutions to confirm main findings are not biased by tax auditing. More details can be referred in Sect. 4.3.2.

The leverage ratio is supposed to increase evaded VAT, as firms face serious cash constraint due to higher debt. PPE and R&D are positively related to evaded VAT, considering firms evade tax to increase internal cash flows for investment activities. With respect to the size, previous studies found that large-sized firms are more compliant than small-and-median firms (Kleven et al., 2011; Kleven et al., 2016). However, the relationship between size and tax evasion is still ambiguous. On the one hand, large-sized firms are more compliant due to the requirement in accurate business records. On the other hand, large-sized firms are more able to manipulate financial figures, leading to lower tax compliance (Rego, 2003).

About 10% (≈23,866/257977) firm-year observations report positive value of evaded VAT, and average evaded VAT for firms reporting positive values of evaded VAT is 136,864 Chinese Yuan.

Prior to the PDR, evaded VAT for treated firms is 13,597 Chinese yuan while 9195 Chinese yuan for the control group.

We use “reghdfe” command in Stata to conduct the empirical analysis. The calculation process automatically drops singletons, i.e., the firm only has one-year observation. Therefore, sample observations for regressions are not the same under different specifications.

We mainly consider the case where never-treated firms as the comparison group. Standard errors are obtained by using a multiplicative wildbootstrap procedure, following Callway and Sant’Anna (2021).

The CSDID command requires no anticipation effect, which implies that taxpayers would not know the PDR in advance. Consider China is a highly political centralized country. Neither firms nor local governments are powerful to bargain with upper-level governments on the selection of pilot industries. With respect to the PDR, the reform was not widely discussed in the media and among the public. Furthermore, VAT payers are not influential to negotiate with tax authorities on the implementation of the reform.

Once a firm is identified as the actual-basis type, its CIT tax is calculated as taxable income declared by the taxpayer, multiplied by statutory taxable income rate.

If a firm is classified as the presumptive-basis type, tax authorities have the discretionary power to assess its taxable income. The assessed taxable income is calculated by multiplying total revenue with the presumptive profit rate given by the tax authority. If tax authorities only have information about firms’ costs and expenses, taxable income can be calculated as, taxable income = total costs and expenses/(1-presumptive profit rate) × presumptive profit rate.

For robustness checks, with respect to the GTS III project, we also represent estimation results by exploiting CSDID method. Results can be referred to in Table A.3.

The coefficient of the PDR variable on input VAT change ratio is -0.344 with robust standard error 0.344. While the coefficient of the PDR on input VAT change ratio for the presumptive group is -0.189 and statistically significant at 99% confidence level.

These contemporaneous tax reduction policies include Business Tax-to-VAT, in which China replaces business tax with VAT in services industry, production-based VAT to consumption-based VAT reform that allowed purchases of fixed assets to be deducted from VAT bases, and so on.

The data are from China Taxation Auditing Yearbook (2009–2016). The tax inspection at provincial level is the finest level we are available to obtain.

For PDR effects on different VAT line items, please refer to Table A.6.

Because the variation in climate conditions is negligible within a province, it is reasonable to assume that provincial-level climate indicators can plausibly proxy city-level climate conditions. City-level indicators are collected from China City Statistical Yearbooks (2009–2012). Provincial-level indicators are collected from China Statistical Yearbooks (2009–2012).

For the effect of the PDR on different VAT line items, please refer to Table A.7.

To further examine whether a significant difference holds between the “high-reliance group” and the “low-reliance group”, we include the interaction between the PDR variable and a dummy indicating whether local economy relies on agricultural industry (1 for the high-reliance group and 0 otherwise) into baseline regressions. Results show that, the coefficient of the triple differences indicator is statistically significant (coefficient is -22.541 while robust standard error is 6.920), which means the policy effect is more pronounced in regions that rely more on agricultural industry.

The China Marketization Report is conducted by China’s National Economic Research Institution. The project started from 2000 and lasts until today. The report measured marketization level for all 31 provinces in mainland China. The marketization score reflects to what extent local government intervenes the market, how competitive the market is, and to what extent local governments protect individuals’ and firms’ rights by justiciable laws. Some Chinese literature provide empirical evidence that higher marketization score is associated with less corruption, as local governments protect producers’ legitimate rights and interests and reduced firms’ tax burden (see Zou and Tao, 2009).

We base the split of low- and high-corruptive regions based on pre-policy periods to avoid any reverse causality. We calculate the indicator from 2001–2004 because the index only exploited unified statistical caliber and calculation method in that period.

References

Alm, J., Jackson, B. R., & Mckee, M. (2009). Getting the word out: Enforcement information dissemination and compliance behavior. Journal of Public Economics, 93, 392–402.

Alm, J., Martinez-Vazquez, J., & McClelland, C. (2016). Corruption and firm tax evasion. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 124, 146–163.

Alm, J., McClelland, G. H., & Schulze, W. D. (1992). Why do people pay taxes? Journal of Public Economics, 48(1), 21–28.

Bellemare, M. F., & Wichman, C. J. (2020). Elasticities and the inverse hyperbolic sine transformation. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 82(1), 50–61.

Benzarti, Y., Carloni, D., Harju, J., & Kosonen, T. (2020). What goes up may not come down: Asymmetric incidence of value-added taxes. Journal of Political Economy, 128(12), 4438–4474.

Besley, T., Jensen, A., \& Persson, T. Norms, enforcement, and tax evasion. 2019, Working paper 25575, National Bureau of Economic Research.

Best, M., Shah, J., & Waseem, M. (2021). Detection without deterrence: Long-run effects of tax audit on firm behavior. Mimeo, University of Manchester.

Callway, B., & Sant’Anna Pedro H. C. (2021). Difference-in-differences with multiple time periods. Journal of Econometrics 225, 200–230.

Carrillo, P. E., Castro, E., & Scartascini, C. (2021). Public good provision and property tax compliance: Evidence from a natural experiment. Journal of Public Economics, 198, 104422.

Casi, E., Spengel, C., & Stage, B. M. B. (2020). Cross-border tax evasion after the common reporting standard: Game over? Journal of Public Economics, 190(10), 104240.

Chan, K. H., Mo, P. L., & Zhou, A. Y. (2013). Government ownership, corporate governance and tax aggressiveness: Evidence from China. Accounting and Finance, 53(4), 1029–1051.

Chaurey, R. (2017). Location-based tax incentives: Evidence from India. Journal of Public Economics, 156, 101–120.

Chen, J. Z., HongHyun, A., Kim, J. B., & \& Ryou, J. W. (2021). Information processing costs and corporate tax avoidance: Evidence from the SEC’s XBRL mandate. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 40(2), 106822.

Correia, S., Guimarães, P., & Zylkin, T. (2020). Fast Poisson estimation with high-dimensional fixed effects. The Stata Journal, 20(1), 95–115.

Dwenger, N., Kleven, H., Rasul, I., & Rincke, J. (2016). Extrinsic and intrinsic motivations for tax compliance: Evidence from a field experiment in Germany. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 8(3), 203–232.

Fack, G., & Landais, C. (2016). The effect of tax enforcement on tax elasticities: Evidence from charitable contributions in France. Journal of Public Economics, 133, 23–40.

Fan, Z. Y., & Liu, Y. (2020). Tax compliance and investment incentives: Firm response to accelerated depreciation in China. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 176, 1–17.

Fisman, R., & Wei, S. J. (2004). Tax rates and tax evasion: Evidence from “missing imports” in China. Journal of Political Economy, 112(2), 471–496.

Frank, M. M., Lynch, L. J., & Rego, S. O. (2009). Tax reporting aggressiveness and its relation to aggressive financial reporting. Accounting Review, 84(2), 467–496.

Goodman-Bacon, A. (2021). Difference-in-differences with variation in treatment timing. Journal of Econometrics, 225(2), 254–277.

Grinberg, I. (2009). Where credit is due: Advantages of the credit-invoice method for a partial replacement VAT. Tax Law Review, 63, 309.

Harju, J., Kosonen, T., & Slemrod, J. (2020). Missing miles: Evasion responses to car taxes. Journal of Public Economics, 181(1), 104108.

Harju, J., Matikka, T., & Rauhanen, T. (2019). Compliance costs vs. tax incentives: Why do entrepreneurs respond to size-based regulations? Journal of Public Economics, 173, 139–164.

Hoseini, M. (2020). Value-added tax, input-output linkages and informality. Economica, 87, 813–843.

Hoseini, M., & Briand, O. (2020). Production efficiency and self-enforcement in value-added tax: Evidence from state-level reform in India. Journal of Development Economics, 14, 102462.

Keen, M. (2009). What do (and don’t) we know about the value added tax? A review of richard M. Bird and Pierre-Pascal Gendron’s the VAT in develo** and transitional Countries. Journal of Economic Literature, 47(1), 159–170.

Kleven, H. J., Knudsen, M. B., Kreiner, C. T., Pedersen, S., & Saez, E. (2011). Unwilling or unable to cheat? Evidence from a tax audit experiment in Denmark. Econometrica, 79(3), 651–692.

Kleven, H. J., Kreiner, C. T., & Saez, E. (2016). Why can modern governments tax so much? An agency model of firms as fiscal intermediaries. Economica, 83(330), 219–246.

Kogler, C., Mittone, L., & Kirchler, E. (2016). Delayed feedback on tax audits affects compliance and fairness perceptions. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 124, 81–87.

Le, T. D., Maleshy, E., & Pham, A. (2020). The impact of local corruption on business tax registration and compliance: Evidence from Vietnam. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 177, 762–786.

Li, J. J., & Wang, X. (2020). Does VAT have higher tax compliance than a turnover tax? Evidence from China. International Tax and Public Finance, 27, 280–311.

Li, P., Lu, Y., & Wang, J. (2016). Does flattening government improve economic performance? Evidence from China. Journal of Development Economics, 123(11), 18–37.

Liu, Y. Z., & Mao, J. (2019). How do tax incentives affect investment and productivity? Firm-level evidence from China? American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 11(3), 261–291.

Lopez-Luzuriaga, A., & Scartascini, C. (2019). Compliance spillovers across taxes: The role of penalties and detection. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 164, 518–534.

Lu, Y., Wang, J., & Zhu, L. (2019). Place-based policies, creation, and agglomeration economics: Evidence from China’s Economic zone program. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 11(3), 325–360.

Luttmer, E. F., & Singhal, M. (2014). Tax morale. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 28(4), 149–168.

Mast, E. (2020). Race to the bottom? Local tax break competition and business location. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 12(1), 288–317.

Metcalf, G. E. (1995). Value-added taxation: A tax whose time has come? Journal of Economic Perspectives, 9(1), 121–140.

Naritomi, J. (2019). Consumers as tax auditors. American Economic Review, 109(9), 3031–3072.

Paetzold, J., & Winner, H. (2016). Taking the high road? Compliance with commuter tax allowances and the role of evasion spillovers? Journal of Public Economics, 143, 1–14.

Pomeranz, D. (2015). No taxation without information: Deterrence and self-enforcement in the value added tax. American Economic Review, 105(8), 2539–2569.

Rego, S. O. (2003). Tax avoidance activities of US multinational corporations. Contemporary Accounting Research, 20(4), 805–833.

Rubolino, E. (2023). Does weak enforcement deter tax progressivity? Journal of Public Economics, 219, 104833.

Slemrod, J., Collins, B., Hoopes, J. L., Reck, D., & Sebastiani, M. (2017). Does credit-card information reporting improve small-business compliance? Journal of Public Economics, 149(3), 1–19.

Torgler, B. (2005). Tax morale in Latin America. Public Choice, 122(1–2), 133–157.

Waseem, M. (2020). The role of withholding in the self-enforcement of a value-added tax: Evidence from Pakistan. Review of Economics and Statistics, 104(2), 336–354.

Waseem, M. (2023). Overclaimed refunds, undeclared sales, and invoice mills: Nature and extent of noncompliance in Value-added tax. Journal of Public Economics, 218(2), 104783.

Winner, H. (2005). Has tax competition emerged in OECD countries? Evidence from Panel Data. International Tax and Public Finance, 12, 667–687.

Zídková, H., & Šastná, A. (2019). VAT collection methods. Acta Universitatis Agriculturae et Silviculturae Mendelianae Brunensis 67(3), 883–895.

Zou, L., & Tao, J. (2009). Government size, market development and corruption. Economic Research, 1, 57–69.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the editor Ronald Davies and two anonymous referees for providing extremely helpful comments. Sixia Chen acknowledges financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 72073145). Shengfeng Lu acknowledges financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 72073103), the Major Project of Key Research Base for Humanities and Social Sciences of the Ministry of Education (No. 22JJD790060), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, and the Research Funds for youth academic team in humanities and social sciences of Wuhan University (413000425), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, and the Research Funds for youth academic team in humanities and social sciences of Wuhan University (413000425).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

See Tables

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20 and

4 and

5.

1.1 The response to suggestions on PAPs purchase receipts

The agriculture business in our country is quite dispersed, and farm producers are not qualified to issue VAT special invoices. However, PAPs purchasing firms need certificates to prove PAPs transactions and claim input tax credits. Therefore, our country allows registered general VAT payers to issue purchase receipts to sellers, while buyers can claim self-calculated input tax credits with the statutory 13% deduction rate for PAPs purchases from VAT-exempted suppliers. As the supportive measures for tax-exempt policies on PAPs, this special regulation prompted agriculture production and circulation activities.

PAPs purchase receipts are issued by buyers and can be used to claim input tax credits, but tax authorities cannot cross-check the validity of these paper trails. Therefore, issuing spurious PAPs purchase invoices is highly prevalent in overclaiming input credits. To consolidate tax enforcement, local SATs adopted a series of management measures. These measures include but are not restricted to, requiring buyers to provide additional transaction certifications, controlling the amount of receipts that sellers can order, and prescribing a limit to buyers on the total purchase expenditure they can issue. These measures improved tax enforcement efficiency to some degree, but also brought extra compliance costs to VAT payers.

To solve above problems, in 2012, after the approval of the State Department, SAT jointly with the Ministry of Finance, issued the No. 38 announcement, i.e., “The announcement on implementing the accredited deduction reform on PAPs input credits among certain pilot industries” (Caishui [2012] 38). The announcement clearly regulated that, since July 1, 2012, any VAT payers that buy PAPs as production materials to produce and sell processed agriculture products in three industries, including the dairy-product-processing industry, the liquor-and-alcohol-production industry, and the edible-oil-processing industry, are obliged to adopt the new method to claim the accredited input credits for PAPs purchases. To enhance the effectiveness of policy implementation while expand the policy coverage, the central SAT and the Ministry of Finance made the No.57 announcement in 2013, i.e., “The announcement on expanding the PDR coverage on pilot industries” (Caishui [2013] 57), authorizing provincial-level SATs to select regional pilot industries conditional on local economic characteristics. We indeed encourage local tax authorities to exploit effective ways to improve a better VAT deduction chain for PAPs purchases.

After the implementation of the PDR, PAPs input credits no longer depend on the old purchase receipts. The policy facilitates VAT payers to reduce management costs, and reporting PAPs input credits becomes easier. On the other side, tax authorities exploit the logic of multi-relationships among sales, costs, expenses, etc. By doing so, tax authorities confirm the validity of input credits claimed by VAT payers. The PDR works in deterring and detecting VAT frauds, making a better operation of the VAT system.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, S., Fang, Y., Lu, S. et al. Tackle spurious invoices challenges to VAT compliance: a quasi-experiment of input VAT deduction reform in China. Int Tax Public Finance (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-023-09805-w

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-023-09805-w