Abstract

The shift to online instruction in higher education related to the COVID-19 pandemic has raised worldwide concerns about an increase in academic misconduct (cheating and plagiarism). However, data to document any increase is sparse. For this study, we collected survey data from 484 students in 11 universities in the USA, and 410 students in five universities in Romania. The data support the conclusions that (1) cheating on exams increased with the shift to online instruction, but plagiarism and cheating on assignments may not have increased, (2) significant differences between the two countries suggest that intervention planning should avoid assuming that results from one context may generalize to another, and (3) influencing student beliefs about rates of AM among their peers may be a fruitful new route for reducing academic misconduct.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

A recent search for the word pandemic in the blog for the International Center for Academic Integrity yielded 37 hits (International Center for Academic Integrity, 2022). These posts routinely raised concerns about increases in academic misconduct (AM) related to the shift to online instruction in the spring of 2020 because of the COVID-19 pandemic. During the 2 years leading up to the writing of this paper, published research on AM in post-secondary institutions during the COVID-19 pandemic has looked at several aspects of this topic more rigorously. For example, early in this time period, science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) instructors in the USA expressed concern that the move to online testing would lead to an increase in cheating (Clark et al., 2020). Similar concerns were reported from the Philippines (Moralista & Oducado, 2020), as well as both university students and faculty in Saudi Arabia (Meccawy et al., 2021). However, these early papers did not offer evidence of changes in the incidence of AM. A later study with a larger sample of instructors in the USA and Canada found that these concerns dropped in 2021 compared to 2020 (Wiley, 2022). Students in the Czech Republic and in Germany reported more cheating in online tests than in in-person tests during the pandemic (Honzíková et al., 2021; Janke et al., 2021). Students in the USA reported cheating for the first time during the pandemic (Jenkins et al., 2022), and the authors concluded that “the COVID-19 pandemic increased first time cheating” (p.1). However, presumably some students cheat for the first time every semester, and the authors did not report comparable data from before the pandemic. In a medical program in Australia, there was no increase in cheating on online book assessments during the pandemic, based on results from text matching software (Ng, 2020). Students in South Africa also reported no increase in AM in general after the start of the pandemic (Verhoef & Coetser, 2021). In contrast, a study of exam-style Chegg requests in five STEM fields found almost a 200% increase in those requests after the start of the pandemic (Lancaster & Cotarlan, 2021). Also, students in the USA believed that there was more cheating in online classes during the pandemic, although this may be related to differences in online versus in-person teaching modes, rather than a change specific to the pandemic (Walsh et al., 2021). Overall, these studies reported inconsistent results with respect to whether or not AM increased during the pandemic. In addition, most of these studies looked at data collected during the pandemic, but were not able to make comparisons to rates prior to the pandemic. These results reflect concerns about an increase in AM related to the pandemic that are not consistently supported by evidence. The significance of this study, in part, is that we have employed a research method that allows us to compare rates of AM before and after the beginning of the pandemic. In addition, we have looked at three different types of AM separately in the data to see if results vary depending on the type of AM.

Literature review

Academic integrity has been defined as a commitment to the values of honesty, trust, fairness, respect, responsibility, and courage in academic work (International Center for Academic Integrity (ICAI), 2021). It follows that academic misconduct (AM) is a violation of those principle in academic work. More specifically, evidence from factor analyses to identify types of AM has been coalescing around three types: cheating on in-class assessments such as exams, cheating on assignments, and plagiarism (Adesile et al., 2016; Akbulut et al., 2008; Colnerud & Rosander, 2009; Ives & Giukin, 2020; Ives et al., 2017).

Prior to the pandemic, many self-report survey studies of post-secondary students yielded data about the relationships between personal characteristics of students and their tendency to engage in AM. In general, the results have been mixed, the effects have been small, and findings have varied across countries and settings. For example, some studies found small but significant differences in AM based on gender (Krueger, 2014; Unal, 2011; Yu et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2018), with women typically having lower rates of AM than men. Other studies did not yield significant differences (Ives et al., 2017; Kucuktepe, 2011; Moberg et al., 2008) or had minimal effects (Awdry & Ives, 2021).

Academic standing is another individual characteristic that has been studied as a predictor of AM. We use the term academic standing to refer to the level of academic work a post-secondary student is engaged in, such as first year, second year, and graduate student. Several studies have looked at the relationship between academic standing and AM. As with gender, results have been mixed, with small effects. Some studies yielded no significant differences across levels of academic standing (Ives et al., 2017; Kucuktepe, 2011). Others have found significant, but small effects (Ives & Giukin, 2020) or mixed results (Watson & Sottile, 2010).

Some studies have found small differences in AM predicted by students’ fields of study, often with students in fields like economics and business having higher rates than students in other fields (Ives & Giukin, 2020; Jurdi et al., 2011; Moberg et al., 2008; Rakovski & Levy, 2007). Others have not found significant differences or small effect sizes (Awdry & Ives, 2021; Ives et al., 2017). These results are difficult to interpret in part because different studies may include different fields of study. However, the typical pattern of minimal to small effect sizes persists across all of these personal characteristics: gender, academic standing, and field of study.

In contrast to individual characteristics, students’ experiences of the AM context around them consistently predict their own AM, often with medium to large effects. For example, how often students believe their peers are plagiarizing or cheating has been a reliable predictor of their own AM (DiPaulo, 2022; McCabe et al., 2012). Similarly, the extent to which students consider AM to be acceptable also reliably predicts their own AM (Bis** et al., 2008; Ives et al., 2017; Jensen et al., 2002; Nonis & Swift, 2001). Another example of this pattern is the consistent finding that how often students observed their peers engaging in AM reliably predicted their own AM (Ives & Giukin, 2020; Ives et al., 2017; O'Rourke et al., 2010; Rettinger & Kramer, 2009; Teodorescu & Andrei, 2009). These predictors related to student experiences and beliefs about AM are consistently stronger predictors of their own AM than predictors based on demographic characteristics.

The COVID-19 pandemic precipitated an abrupt shift worldwide to online instruction for many students in higher education. This shift raised concerns about increased AM during the pandemic. However, existing empirical evidence for an increase in AM related to the pandemic is scarce, in part because previous studies have not compared data from before and after the beginning of the pandemic. For these reasons, the objectives of this study are to (1) determine if these concerns are supported by empirical evidence, to (2) determine whether any changes in AM vary across different types of AM, and to (3) see if patterns of AM vary across the two countries. To investigate the objectives, we collected data in both the USA and Romania. We chose these countries for three reasons. First, scholars have argued for a stronger culture of academic dishonesty in Eastern European compared to western countries, perhaps inherited from their history under communism (Badea-Voiculescu, 2013; Cole, 2013; Mungiu-Pippidi, 2011; Stan & Turcescu, 2004). Second, rates of AM tend to be higher in Romania than in the USA (Ives et al., 2017). Third, this work builds on a preexisting and productive working relationship between scholars in both countries.

Data were collected in these two countries to address the following research questions:

-

To what extent did beliefs and experiences of academic misconduct change after the COVID-19 shift to online instruction for each country?

-

Were changes in beliefs and experiences of academic misconduct different between the two countries?

-

Do academic standing, gender identity, or field of study predict changes in beliefs and experiences of academic misconduct after the COVID-19 shift to online instruction for each country?

-

To what extent did sources used for academic misconduct change after the COVID-19 shift to online instruction for each country?

Methods

Instrument

An original survey was developed for this study based on previous research combined with the specific interest in changes in AM related to the move to online instruction at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. After reviewing an information sheet and consenting to participate in the study, participants could respond to specific demographic items asking about academic standing, country where they study, gender identity, and field of study.

Following these demographic items, the heart of the student survey included a set of 18 items based on all possible combinations of three types of AM (cheating on exams, cheating on assignments, and plagiarism) (Adesile et al., 2016; Ives & Giukin, 2020; Ives et al., 2017), two time periods (the year before and the year since the beginning of the pandemic), and three types of experiences (how often they believed their peers were engaging in AM, how many times they observed peers engaging in AM, and how many times the participants themselves engaged in AM) (Ives et al., 2017; O'Rourke et al., 2010; Rettinger & Kramer, 2009; Teodorescu & Andrei, 2009). For example, the first of these items in the English version of the instrument was During the year BEFORE the pandemic started, what percent of students do you believe were cheating on examinations? This item included cheating on exams as the type of AM, before the pandemic as the time period, and belief about the rate of peer engagement as the type of experience.

Given the circumstances around the transition caused by the pandemic, it was not practical to run randomized controlled trials, or some other repeated measures design, to address the research questions. Using a retrospective pretest approach was more appropriate for these circumstances (Pelfrey & Pelfrey, 2009). The retrospective pretest design “involves asking participants at the time of the posttest to retrospectively respond to questionnaire items thinking back to a specified pretest period. In effect, participants rate each item twice within a single sitting (‘then’ and ‘now’) to measure self-perceptions of change” (Little et al., 2020, p. 175). The retrospective pretest approach also may mitigate response shift bias. This occurs when data are collected over time, but standards or understandings about the constructs being measured shift over time. For example, if we had collected data over time, in a repeated measures model, our participants’ understanding of plagiarism could shift over that time so that their early responses are based on different understandings of plagiarism than their later responses (Howard & Dailey, 1979; Howard et al., 1979). The retrospective pretest approach has been used to investigate a variety of topics in the field of education, including accessibility and quality of instruction before and after the pandemic (Ives, 2021), as well as teacher efficacy beliefs (Cantrell, 2003), effectiveness of academic instruction (Coulter, 2012), and professional development (Sullivan & Haley, 2009). Recently, retrospective pretest was also used to investigate changes in students concerns about cheating before and after the beginning of the pandemic (Daniels et al., 2021). In the study reported here, the retrospective pretest allowed us to compare results before and after the transition to online instruction related to the pandemic, which contributes to the significance of the study.

In addition, the survey included six items asking about sources used for AM. Six of the 18 items described above asked about participants’ own engagement in AM. For these six items, they were also asked to select from a list of eight possible resources for help for their AM. Participants were encouraged to select all resources from the list that applied to them. These resources were the following: web sites/Internet, created resources myself, another student, friend (not student), family member, purchased from outside sources, library, and other (please describe).

Participants were recruited through an existing network of research colleagues in the USA and in Romania. Through this network, post-secondary students were invited to complete the anonymous online survey. Post-secondary students from eleven universities in the USA (N = 414) and five universities in Romania (N = 480) responded to the survey. The class standing of those participants included 119 first year students, 213 s year students, 214 third year students, 120 fourth year students, and 121 graduate students. The relatively low number of fourth year students reflects the fact that typical Bachelor degrees in the USA are based on 4-year programs, while those in Romania are typically 3-year programs. Most participants identified as female (627), while 255 identified as male, and 28 identified as other. Field of study was based on the classifications used by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) (UNESCO Institute for Statistics. (2015). International Standard of Classification: Fields of Education and Training 2013 (ISCED-F 2013)—Detailed Field Descriptions. Retrieved from Montreal, 2013). The number of participants in each field of study was:

-

Generic 6

-

Education 110

-

Arts/Humanities 73

-

Social Sciences 175

-

Business 188

-

Natural Sciences 75

-

Information Tech 22

-

Engineering 139

-

Agriculture 22

-

Health/welfare 84

-

Services 8

Results

To what extent did beliefs and experiences of academic misconduct change after the COVID-19 shift to online instruction for each country?

To address this question, we ran two series of nine paired samples two-tailed t-tests, one series for each country, on the responses from the relevant items of the instrument as described in the “Methods” section. Each item asked about one of three types of academic misconduct, one time period, and one of the three types of experiences. We tested whether mean responses for these nine conditions were significantly different for pretest (retrospective) versus posttest (after the shift to online instruction). Given that we were running nine tests for each country, we adjusted for type 1 error inflation by approximating the Bonferroni adjustment (Dunn, 1961), changing the alpha level to 0.006. We also reported a Cohen’s d effect size (Cohen, 1988). Although Cohen’s d is vulnerable to a small sample bias (Hedges & Olkin, 1985), our samples are large enough that this bias would not affect results for at least two decimal places. Recognizing that p-values can never actually equal zero, we listed p < 0.001 if the rounded result was 0.000. Negative test statistics indicate that the mean after the shift to online instruction was higher than the mean before that shift. In other words, negative test statistics indicate that AM increased after the beginning of the pandemic. Results for these t-tests are shown in Tables 1 and 2.

Three patterns in these results are notable. First, when Romanian students reported their own behaviors, none of the three comparisons were statistically significant, and none of them had effect sizes that reached the threshold to be small effects (Cohen, 1988). Second, five of the other six comparisons for Romanians were statistically significant, with three of those exceeding the threshold for small effects, and one other reaching the threshold for a large effect. Third, all of the significant comparisons reflected increases in cheating and plagiarism after the transition to online instruction. These results suggest that Romanian students believe their peers are cheating and plagiarizing more after the beginning of the pandemic, even though their own rates of cheating and plagiarism did not change significantly.

Results for the students in the USA were somewhat different from those in Romania. First, when students in the USA reported their own behaviors, the increase in cheating on exams was statistically significant with a small effect size. The increase in cheating on assignments was also significant, but the effect size did not reach the threshold of the small range. Students in the USA did not report a significant increase in observing others plagiarize or in the frequencies of their own plagiarizing. Like for the Romanians, all of the significant comparisons for the USA reflected increases in cheating and plagiarism after the transition to online instruction.

Were changes in beliefs and experiences of academic misconduct different between the two countries?

To address this question, we calculated gain scores by subtracting pretest scores from posttest scores for each of the nine different permutations of other conditions. For example, we subtracted the pretest scores for observing others commit plagiarism from the corresponding posttest scores. Then, we ran a series of nine independent samples two-tailed t-tests on those gain scores to identify significant differences between countries. We adjusted the alpha level to 0.005 to control for type 1 error inflation, and reported adjusted results when equal variances were not assumed. Positive means indicate an increase in academic misconduct. A positive test statistic indicates that the increase for Romanian participants was greater than the increase for participants from the USA. These results are reported in Table 3.

With the adjusted alpha value, three of these comparisons were statistically significant. First, Romanian students reported a greater increase than students in the USA in observing others cheating on exams after the transition to online instruction. The effect was small, and there was no significant difference between the two groups in reporting changes in their own cheating on exams. Secondly, students in the USA reported a significantly larger increase than Romanians in their estimates of what proportion of other students were cheating on assignments. In fact, Romanians reported a small decrease in these estimates. This effect was large. The same pattern occurred in the third significant difference, also related to cheating on assignments. Students in the USA reported a significantly larger increase than Romanians in their own cheating on assignments. In fact, Romanians reported a small decrease in their own cheating on assignments. This effect was small. None of the comparisons related to plagiarism were significant with the adjusted alpha, although two of them yielded p-values below the conventional 0.05 alpha level, with effect sizes close to the lower threshold for a small effect size.

Two-way ANOVA was used to investigate main effects and interactions between country and time across nine conditions. The nine conditions were derived from all combinations of the three types of academic misconduct (cheating on examinations, cheating on assignments, and plagiarism) and the three types of experiences (estimated percent of students engaging, number of incidents observed, number of times actually committing). The time period (before the pandemic — pretest, and during the pandemic — posttest) was used as a within subject factor and the country (Romania versus USA) was used as between subject factor. Eta squared was computed as a proportion of variance effect size. These results can be seen in Table 4, organized by condition.

The mixed ANOVA tests revealed significant interaction and main effects for the majority of the misconduct behaviors, with the pattern of the results showing that the prevalence of the misconduct behaviors was higher during the pandemic, and the Romanian students reporting higher frequencies than USA students. However, only one of these interactions accounted for more than 1% of the total variance, which is the minimum conventional criterion for a small effect. The results showed that the rates of academic misconduct before the COVID-19 pandemic were significantly higher for Romanian students than US students except for the percent of students believed to be cheating on assignments. During the pandemic, the patterns were similar, except for the students’ own cheating behavior and the percent of students cheating on examinations, which did not reveal significant differences between the two countries. Only one misconduct behavior was higher for US students during COVID-19; the percent of students they believed were cheating on assignments. The differences between the two periods (before and during COVID-19) showed the number of misconduct behaviors was higher during the pandemic with only a few exceptions, the Romanian students reported that they plagiarized and cheated slightly more on assignments before the pandemic.

Do academic standing, gender identity, or field of study predict changes in beliefs and experiences of academic misconduct after the COVID-19 shift to online instruction for each country?

To address this question, we ran one-way ANOVAs using each of the three categorical characteristics variables as predictors of differences between pre and post scores on the three types of AM beliefs and experiences. This yielded 27 ANOVAs, and we adjusted the alpha level to 0.001 accordingly. Results for these ANOVAs can be seen in Table 5.

For cheating on exams, academic standing significantly predicted changes in students’ beliefs about how often their peers were cheating as well as how often they had observed their peers cheating, with small effect sizes in both cases. However, academic standing did not predict changes in self-reported cheating on exams, and the effect size was minimal.

Cheating on assignments yielded a similar pattern. Again, what students believed and observed about the cheating of their peers was significantly predicted by academic standing, with a medium and small effect size, respectively. Academic standing approached significance as a predictor of self-reported changes in cheating, with a smaller effect size than either of the other two.

The pattern for plagiarism was quite different. Students reported no significant changes in how often they believed their peers were engaged in plagiarism, how often they observed their peers engage in plagiarism, or their own rates of plagiarism. The effect size for self-reporting was the only one of the three that just reached the threshold for a small effect.

Tukey tests on the statistically significant ANOVAs yielded significant pairwise comparisons between graduate students and some undergraduate groups for their estimates of peer cheating on exams and assignments, as well as their observations of peers cheating on exams and assignments. In every case, graduate students reported a smaller increase in these beliefs and observations than undergraduates did. There were no significant differences between groups for self-reports on any type of AM. There were also not significant differences between any groups for any belief or experience related to plagiarism.

A similar set of ANOVAs was run for gender. For gender, none of the comparisons were statistically significant, even without a Bonferroni adjustment to the alpha levels, with significance values ranging from 155 to 0.944. The largest eta-squared point estimate of effect size was 0.006, which does not meet the minimum threshold for a small effect.

A third similar set of ANOVAS was run for field of study, again with an adjusted alpha level of 0.001. The ANOVAs for field of study also yielded no statistically significant results, with significance values ranging from 0.003 to 0.906. Eta-squared effect sizes ranged from 0.005 to 0.030, in the minimal to small ranges.

To what extent did sources used for academic misconduct change after the COVID-19 shift to online instruction for each country?

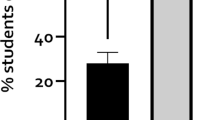

Table 6 reports frequency counts, the number of times that participants reported using each of the listed sources for before and after the start of the pandemic, sorted by the three types of AM. A chi-square analysis of the frequency counts for cheating on exams resulted in a statistically significant pattern (Pearson chi-square = 27.813, p < 0.001). Figure 1 provides a visual representation of these changes in the use of sources for cheating on exams and shows that there were notable increases in the use of online resources and self-generated resources for cheating on exams. Pearson chi-square analyses of sources for cheating on assignments and plagiarism did not yield significant results (Pearson chi-square = 7.307, p = 0.293, and Pearson chi-square = 2.509, p = 0.867, respectively). While some other increases for cheating on exams are notable by percent, the actual frequency counts are low (< 40) making these inferences less reliable. There were no notable changes in the use of sources for either cheating on assignments or plagiarism. These results are consistent with the finding that students from the USA reported an increase in cheating on exams after the start of the pandemic.

Discussion

Validity

An important potential limitation of this study is that we designed an original instrument for our data collection, which raises the question of the validity of results. For this reason, we took a number of steps to ensure, and document, the validity of the results. Statistical results for these validity checks were not included in the “Results” section because they did not apply directly to the research questions.

-

We implemented a well-documented method that is appropriate for the research questions. Prior use of the retrospective pretest approach in peer-reviewed literature helps to validate our method in this study (Cantrell, 2003; Coulter, 2012; Daniels et al., 2021; Ives, 2021; Sullivan & Haley, 2009).

-

The items in the survey were based on items previously used in peer-reviewed research (Adesile et al., 2016; Ives & Giukin, 2020; Ives et al., 2017; O'Rourke et al., 2010; Rettinger & Kramer, 2009; Teodorescu & Andrei, 2009).

-

Social desirability is the tendency for participants to give responses that place them in a positive light. Social desirability may be a threat to validity for any self-reported data collection. In the case of AM, participants may offer responses that minimize their engagement in AM behaviors. A few studies have evaluated this concern for self-report surveys about AM and found no evidence that social desirability influenced the results (Bazzy et al., 2017; Lucas & Friedrich, 2005; McTernan et al., 2014; Trost, 2009).

-

In addition, our data replicate patterns found in previous studies. For example, prior research has found that predictions of AM based on academic standing, gender, and field of study tend to yield weak effects. Using one-way ANOVAs, we examined differences in mean scores for all three types of AM, across both time periods, and all three types of experiences, with academic standing as the predictor in each case. After adjusting for type 1 error inflation, 12 of the 18 tests were statistically significant, with eta-squared effect sizes for the significant comparisons ranging from 0.023 to 0.072. These effects fall in the small range and below (Cohen, 1988). A parallel set of one-way ANOVAs for gender yielded no statistically significant differences across the 18 comparisons. The largest eta-squared estimate of proportion of variance accounted for was 0.009, indicating that these differences are minimal. A third parallel set of one-way ANOVAs was run to identify significant differences in AM beliefs and experiences across academic fields of study. Even without a Bonferroni adjustment to the alpha levels, only one of the 18 comparisons was statistically significant. These results are consistent with previous research for all three predictors (e.g., Jurdi et al., 2011; Kucuktepe, 2011; Watson & Sottile, 2010; Zhang et al., 2018).

-

Our participant representation across the 11 UNESCO fields of study and training is not consistent. For four of the 11 fields, we have fewer than 50 participants. However, the fact that only one of 18 comparisons across fields of study was significant suggests that any threat to validity from this disproportionate representation is minimal.

-

Prior research has also found that students’ beliefs about the AM of their peers, and their observations of peer AM, are positively correlated with their own engagement in AM, with larger effect sizes than those for the personal characteristics noted above. We ran a total of twelve one-tailed Pearson correlations, predicting students’ engagement in each of the three types AM, across each of the two time periods, based on both estimates of peer AM rates, and number of times peers were observed to engage in AM. All of these twelve correlations were statistically significant (p < 0.001). For each type of AM and time period, the correlation was higher for number of times peers were observed to engage in AM, than for estimated peer AM rates. Proportions of variance ranged from 0.137 to 0.314 for predictions based on the number of times peers were observed to engage in AM, indicating medium to large effect sizes. Proportions of variance for the estimated rates of peer engagement in AM were lower, ranging from 0.078 to 0.145, indicating small to medium effect sizes. These results are consistent with prior studies (DiPaulo, 2022; Ives & Giukin, 2020; Ives et al., 2017; McCabe et al., 2012; O'Rourke et al., 2010; Rettinger & Kramer, 2009; Teodorescu & Andrei, 2009).

-

Based on prior research, we also predicted that self-reported rates of AM would be higher for Romanian students than for US students both before and after the beginning of the pandemic. To test this prediction, we ran a series of six independent samples two-tailed t-tests on the responses from the relevant items of the instrument. Mean rates of Romanian AM were higher than mean US rates in all six cases, and this difference was statistically significant in five of the six comparisons. The one exception was cheating on assignments during the pandemic, which also had a minimal effect size. The other five effect sizes included one minimal, two small, one medium, and one large. This finding is also consistent with the limited available literature. Scholars have expressed concern about academic integrity in Romanian higher education, attributing this problem to cultural characteristics in the country and in the system of higher education (Badea-Voiculescu, 2013; Cole, 2013; Comsa et al., 2007; Galloway, 2013; Mungiu-Pippidi, 2011; Stan & Turcescu, 2004; Teodorescu & Andrei, 2009). While recent efforts by academics in Romania to reduce AM in classrooms has made some progress, government corruption continues to tarnish the image of Romania as it struggles to address evidence of plagiarism among officials (Bailey, 2022). However, academic integrity prevalence data for Romania and neighboring countries is scarce. Academic misconduct rates reported by university students in Romania are higher than those typically reported in the USA and other developed countries (Ives et al., 2017), generally exceeding 90%, although this may not be the case specifically for outsourcing assignments (Awdry & Ives, 2021).

Discussion related to the research questions

-

To what extent did beliefs and experiences of academic misconduct change after the COVID-19 shift to online instruction for each country?

Romanian students did not report significant increases for any of the three types of AM after the beginning if the pandemic, despite reporting that they believed that their peers were engaging in AM significantly more, and that they had observed their peers engage in AM significantly more in almost all cases. By contrast, while US students generally also reported that their peers were engaging in AM significantly more, and that they had observed their peers engage in AM significantly more, they also reported significant increases in their own cheating on assignments and cheating on exams. US students did not report a significant increase in their own plagiarism after the beginning of the pandemic. Even in the two cases where US students reported an increase in their own AM, the effect sizes for their beliefs and observations about others were larger. Generally, we conclude that students overestimate the AM of their peers relative to their own behavior. Given that these beliefs and observations are stronger predictors of AM than personal characteristics, one recommendation for reducing the rate of AM is to provide students with specific data about rates of AM in their institutions, to see if knowledge of this institutional data would reduce AM (Awdry & Ives, 2022). We know of no efforts to implement this recommendation, so this intervention may warrant further study for effectiveness.

It is perhaps not surprising that neither group reported a significant increase in plagiarism. Plagiarism is typically carried out outside of the classroom, so opportunities for plagiarism would not have changed as a result of a shift to online instruction. Unlike the Romanian students, the US students reported a significant increase in both cheating on exams and cheating on assignments. However, the effect size for cheating on assignments did not rise to the conventional threshold for a small effect, while the effect size for cheating on exams did. These findings for cheating on assignments are similar to those of Ng (2020), who found no increase in cheating on online book assignments for students in a medical program in Australia. As with plagiarism, cheating on assignments is typically carried out outside the classroom. However, cheating on exams would more often be carried out in the classroom before the shift to online instruction. These results indicate that the US students may have taken advantage of additional opportunities to cheat in exams after the shift to online instruction. This conclusion is supported by the observation that, although the Romanian students did not report a significant increase in cheating on exams, their effect size for cheating on exams was stronger in support of an increase with online instruction than the effect sizes for the other two types of AM, which actually slightly favored small decreases in cheating on assignments and plagiarism. These results are consistent with previous findings related to increased cheating on online exams after the pandemic began (Honzíková et al., 2021; Janke et al., 2021; Lancaster & Cotarlan, 2021). It appears that cheating on exams increased when instruction shifted to online at the beginning of the pandemic, while cheating on assignments and plagiarism did not. Based on these results, we recommend that concerns about AM related to the pandemic in particular, and online instruction in general, should distinguish between different types of AM, and focus on cheating on exams as a greater concern than cheating on assignments or plagiarism. It is important to note here that research on beliefs about peer AM and observations of peer AM as predictors of students’ own AM are correlational, while interventions that rely on these relationships would be assuming causal relationships.

-

Were changes in beliefs and experiences of academic misconduct different between the two countries?

Most of the differences in changes in beliefs and experiences across the two countries were not significant. Three of these were significant, and one of those had a large effect size. Romanians reported a small decrease in how often they believed their peers were cheating on assignments, while the US students reported a larger increase in this belief. These beliefs are related to a small but significant difference in these students’ engagement in cheating on assignments. Here again, Romanians reported a small decrease in how often they cheated on assignments, while the US students reported a larger increase in their cheating on assignments. These results reinforce the recommendation that interventions to reduce AM should include more information for students about the institutional rates of AM, with the same caveat about causality mentioned above.

-

Do academic standing, gender identity, or field of study predict changes in beliefs and experiences of academic misconduct after the COVID-19 shift to online instruction for each country?

Collapsing the data across the two countries, neither gender nor field of study were significant predictors of changes in beliefs, observations, or engagement in any types of AM. Academic standing did yield some significant results, with graduate students reporting smaller changes in AM beliefs, observations, and engagement, than undergraduates. Undergraduates reported a significantly larger increase in cheating on assignments than graduate students reported, with a small effect. This may be related to the small increase in cheating on assignments reported by the US students, but in any case, the general pattern for these three characteristics-based predictors is that their relationships to increases in beliefs, observations, and AM are unremarkable.

-

To what extent did sources used for academic misconduct change after the COVID-19 shift to online instruction for each country?

We did not find a significant change in the types of resources students used before and after the beginning of the pandemic for cheating on assignments or for plagiarizing. However, we did find a significant change in resources used for cheating on exams, with an increase in the use of online resources as well as an increase in the use of materials that students created themselves. This is consistent with results from two other countries where increases in cheating on online exams were reported (Honzíková et al., 2021; Janke et al., 2021). When students are attending in-person classes, plagiarism and cheating on assignments typically takes place outside of class, while cheating on exams takes place during class. However, after the move to online instruction, exams also take place outside of class. This change in setting for exams may explain the increase in the use of online materials for cheating. Additional research is needed to confirm this connection between increased used of online resources and the application of those resources to online exams. At the same time, interventions to reduce the use of online resources on exams could include online monitoring of exams, as well as revising exam format and content to require more individualized responses (Ives & Nehrkorn, 2019).

Overall, our results show that concerns about an increase in AM resulting from the shift to online instruction in the spring of 2020 are masking complexities that warrant further examination. This is a mixture of both good news and bad news. First, not all types of AM are equally related to this shift. We found no significant change in rates of plagiarism, for example, while increases in cheating on exams are supported by our data. Intervention planning should take into consideration which types of AM are being addressed. Second, we found significant differences between the two countries. Intervention planning should avoid making assumptions about how results from one context may generalize to another. Third, although the quality and quantity of existing research on effective interventions to reduce AM have been widely criticized (Baird & Clare, 2017; Cronan et al., 2017; Henslee et al., 2015; Ives & Nehrkorn, 2019; Lavin et al., 2020; Marshall & Vernon, 2017; Obeid & Hill, 2017), influencing student beliefs about rates of AM may be a fruitful new route for effective intervention.

Data Availability

Data are available from the corresponding author.

References

Adesile, I., Nordin, M. S., Kazmi, Y., & Hussein, S. (2016). Validating Academic Integrity Survey (AIS): An application of exploratory and confirmatory factor analytic procedures. Journal of Academic Integrity, 14, 149–167. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-016-9253-y

Akbulut, Y., Sendag, S., Birinci, G., Kilicer, K., Sahin, M. C., & Odabasi, H. F. (2008). Exploring the types and reasons of internet-triggered academic dishonesty among Turkish undergraduate students: Development of Internet-Triggered Academic Dishonesty Scale (ITADS). Computers & Education, 51(1), 463–473. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2007.06.003

Awdry, R., & Ives, B. (2021). Students cheat more often from those known to them: Situation matters more than the individual. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 46(8), 1254–1268. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2020.1851651

Awdry, R., & Ives, B. (2022). International Predictors of Contract Cheating in Higher Education. Journal of Academic Ethics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-022-09449-1

Badea-Voiculescu, O. (2013). Attitude of Romanian medical students towards plagiarism. Romanian Journal of Morphology and Embryology, 5, 907–908.

Bailey, J. (2022). How Romania’s Prime Minister was “Cleared” of plagiarism. Retrieved June 29, 2022, from https://www.plagiarismtoday.com/2022/06/29/how-romanias-prime-minister-was-cleared-of-plagiarism/?utm_source=newsletter&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=how_romania_s_prime_minister_was_cleared_of_plagiarism_plagiarism_today&utm_term=2022-06-29. Accessed 30 June 2022

Baird, M., & Clare, J. (2017). Removing the opportunity for contract cheating in business capstones: a crime prevention case study. International Journal for Educational Integrity, 13, Article 6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40979-017-0018-1

Bazzy, J. D., Woehr, D. J., & Borns, J. (2017). An examination of the role of self-control and impact of ego depletion on integrity testing. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 39(2), 101–111. https://doi.org/10.1080/01973533.2017.1283502

Bis**, T. O., Patron, H., & Roskelley, K. (2008). Modeling academic dishonesty: The role of student perceptions and misconduct type. Journal of Economic Education, 39(1), 4–21. https://doi.org/10.3200/jece.39.1.4-21

Cantrell, P. (2003). Traditional vs. retrospective pretests for measuring science teaching efficacy beliefs in preservice teachers. School Science and Mathematics, 103(4), 177–185. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1949-8594.2003.tb18116.x

Clark, T. M., Callam, C. S., Paul, N. M., Stoltzfus, M. W., & Turner, D. (2020). Testing in the time of COVID-19: A sudden transition to unproctored online exams. Journal of Chemical Education, 97, 3413–3417.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (Second ed.). Erlbaum

Cole, M. (2013). Corruption in universities: A blueprint for reform. Times Higher Education. https://www.timeshighereducation.com/comment/opinion/corruption-in-universities-a-blueprint-for-reform/2009139.article

Colnerud, G., & Rosander, M. (2009). Academic dishonesty, ethical norms and learning. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 34(5), 505–517.

Comsa, M., Tufis, C. D., & Voicu, B. (2007). Romanian academic system: Teachers’ and students’ opinions. Fundatia. http://www.fundatia.ro/sites/default/files/en_36_romanian%20academic.pdf. Accessed 28 March 2016

Coulter, S. E. (2012). Using the retrospective pretest to get usable, indirect evidence of student learning. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 37(3), 321–334. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2010.534761

Cronan, T. P., McHaney, R., Douglas, D. E., & Mullins, J. K. (2017). Changing the academic integrity climate on campus using a technology-based intervention. Ethics & Behavior, 27(2), 89–105. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508422.2016.1161514

Daniels, L. M., Goegan, L. D., & Parker, P. C. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 triggered changes to instruction and assessment on university students’ self-reported motivation, engagement and perceptions. Social Psychology of Education, 24, 299–318. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-021-09612-3

DiPaulo, D. (2022). Do preservice teachers cheat in college, too? A quantitative study of academic integrity among preservice teachers. International Journal for Educational Integrity, 18(2). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40979-021-00097-3

Dunn, O. J. (1961). Multiple comparison among means. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 56, 52–64.

Galloway, A. (2013). The culture of plagiarized dissertations in Romania - A call for inquiry in the Humanities - and beyond. Integru. http://integru.org/opinions/the-culture-of-plagiarized-dissertations-in-romania-a-call-for-inquiry-in-the-humanities-and-beyond

Hedges, L. V., & Olkin, I. (1985). Statistical methods for meta-analysis. Academic Press.

Henslee, A., Goldsmith, J., Stone, N. J., & Krueger, M. (2015). An online tutorial vs. pre-recorded lecture for reducing incidents of plagiarism. American Journal of Engineering Education, 6(1), 27–32.

Honzíková, J., Aichinger, D., Krotky, J., & Bajtoš, J. (2021). Prevalence of academic cheating in the university during the Covid-19 pandemic-caused shift towards online learning. Journal of Technology and Information Education, 13(1), 135–149. https://doi.org/10.5507/jtie.2021.014

Howard, G. S., & Dailey, P. R. (1979). Response-shift bias: A source of contamination of self-report measures. Journal of Applied Psychology, 66(2), 144–150.

Howard, G. S., Ralph, K. M., Gulanick, N. A., Maxwell, S. E., Nance, S. W., & Gerber, S. K. (1979). Internal invalidity in pre-test-post-test self-report evaluations and a re-evaluation of retrospective pre-tests. Applied Psychological Measurement, 3, 1–23.

International Center for Academic Integrity. (2022). Integrity Matters Blog. International Center for Academic Integrity. Retrieved June 22, 2022 from https://academicintegrity.org/blog. Accessed 15 June 2022

International Center for Academic Integrity (ICAI). (2021). The fundamental values of academic integrity. I. C. f. A. Integrity. https://academicintegrity.org/images/pdfs/20019_ICAI-Fundamental-Values_R12.pdf. Accessed 15 June 2022

Ives, B., & Nehrkorn, A. (2019). A research review: Post-secondary interventions to improve academic integrity. In D. Velliaris (Ed.), Prevention and detection of academic misconduct in higher education (pp. 39–62). IGI Global

Ives, B., Alama, M., Mosora, L. C., Mosora, M., Grosu-Radulescu, L., Clinciu, A. I., . . . Dutu, A. (2017). Patterns and predictors of academic dishonesty in Romanian university students. Higher Education, 74(5), 815–831. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-016-0079-8

Ives, B., & Giukin, L. (2020). Patterns and predictors of academic dishonesty in Moldovan University students. Journal of Academic Ethics, 18(1), 71–88. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-019-09347-z

Ives, B. (2021). University students experience the COVID‑19 induced shift to remote instruction International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 18(59). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-021-00296-5

Janke, S., Rudert, S. C., Petersen, Ä. n., Fritz, T. M., & Daumiller, M. (2021). Cheating in the wake of COVID-19: How dangerous is ad-hoc online testing for academic integrity? Computers and Education Open, 2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeo.2021.100055

Jenkins, B. D., Golding, J. M., Le Grand, A. M., Levi, M. M., & Pals, A. M. (2022). When opportunity knocks: College students’ cheating amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Teaching of Psychology, 0(0), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/00986283211059067

Jensen, L. A., Arnett, J. J., Feldman, S. S., & Cauffman, E. (2002). It’s wrong, but everybody does it: Academic dishonesty among high school and college students. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 27, 209–228. https://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.2001.1088

Jurdi, R., Hage, H. S., & Chow, H. P. H. (2011). Academic dishonesty in the Canadian classroom: Behaviours of a sample of university students. Canadian Journal of Higher Education, 41(3), 1–35.

Krueger, L. (2014). Academic dishonesty among nursing students. Journal of Nursing Education, 53(2), 77–87.

Kucuktepe, S. E. (2011). Evaluation of tendency towards academic dishonesty levels of psychological counseling and guidance undergraduate students. Procedia Social and Behavioral Sciences, 15, 2722–2727. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.04.177

Lancaster, T., & Cotarlan, C. (2021). Contract cheating by STEM students through a file sharing website: A Covid-19 pandemic perspective. International Journal for Educational Integrity, 17(3). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40979-021-00070-0

Lavin, C. E., Mason, L. H., LeSueur, R., & Haspel, P. (2020). The dearth of published intervention studies about English learners with learning disabilities or emotional and behavioral disorders in special education. Learning Disabilities: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 25(1), 18–28. https://doi.org/10.18666/LDMJ-2020-V25-I1-10203

Little, T. D., Chang, R., Gorrall, B. K., Waggenspack, L., Fukuda, E., Allen, P. J., & Noam, G. G. (2020). The retrospective pretest–posttest design redux: On its validity as an alternative to traditional pretest–posttest measurement. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 44(2), 175–183. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025419877973

Lucas, G. M., & Friedrich, J. (2005). Individual differences in workplace deviance and integrity as predictors of academic dishonesty. Ethics & Behavior, 15(1), 15–35.

Marshall, L. L., & Vernon, A. W. (2017). Attack on academic dishonesty: What ‘lies’ ahead? Journal of Academic Administration in Higher Education, 13(2), 31–40.

McCabe, D. L., Butterfield, K. D., & Treviño, L. K. (2012). Cheating in college: Why students do it and what educators can do about it. Johns Hopkins University Press.

McTernan, M., Love, P., & Rettinger, D. (2014). The influence of personality on the decision to cheat. Ethics & Behavior, 24(1), 53–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508422.2013.819783

Meccawy, Z., Meccawy, M., & Alsobhi, A. (2021). Assessment in ‘survival mode’: student and faculty perceptions of online assessment practices in HE during Covid-19 pandemic. International Journal for Educational Integrity 17(16). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40979-021-00083-9

Moberg, C., Sojka, J. Z., & Gupta, A. (2008). An update on academic dishonesty in the college classroom. Journal on Excellence in College Teaching, 19(1), 149–176.

Moralista, R. B., & Oducado, R. M. F. (2020). Faculty perception toward online education in a state college in the Philippines during the Coronavirus Disease 19 (COVID-19) pandemic. Universal Journal of Educational Research, 8(10), 4736–4742. https://doi.org/10.13189/ujer.2020.081044

Mungiu-Pippidi, A. (2011). Civil society and control of corruption: Assessing governance of Romanian public universities. International Journal of Educational Development. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1790062

Ng, C. K. C. (2020). Evaluation of academic integrity of online open book assessments implemented in an undergraduate medical radiation science course during COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Medical Imaging and Radiation Sciences, 51, 610–616. https://doi.org/10.1016/jmir.2020.09.009

Nonis, S. A., & Swift, C. O. (2001). An examination of the relationship between academic dishonesty and workplace dishonesty: A multicampus investigation. Journal of Education for Business, 77(2), 69–77.

Obeid, R., & Hill, D. B. (2017). An intervention designed to reduce plagiarism in a research methods classroom. Teaching of Psychology, 44(2), 155–159. https://doi.org/10.1177/0098628317692620

O’Rourke, J., Barnes, J., Deaton, A., Fulks, K., Ryan, K., & Rettinger, D. A. (2010). Imitation is the sincerest form of cheating: The influence of direct knowledge and attitudes on academic dishonesty. Ethics & Behavior, 20(1), 47–64. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508420903482616

Pelfrey, W. V., & Pelfrey, W. V. (2009). Curriculum evaluation and revision in a nascent field: The utility of the retrospective pretest–posttest model in a Homeland Security program of study. Evaluation Review, 33(1), 54–82.

Rakovski, C. C., & Levy, E. S. (2007). Academic dishonesty: Perceptions of business students. College Student Journal, 42(2), 466–481.

Rettinger, D. A., & Kramer, Y. (2009). Situational and personal causes of student cheating. Research in Higher Education, 50, 293–313. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-008-9116-5

Stan, L., & Turcescu, L. (2004). Politicians, intellectuals, and academic integrity in Romania. Problems of Post- Communism, 51(4), 12–24.

Sullivan, L. G., & Haley, K. J. (2009). Using a retrospective pretest to measure learning in professional development programs. Community College Journal of Research and Practice, 33(3–4), 346–362. https://doi.org/10.1080/10668920802565052

Teodorescu, D., & Andrei, T. (2009). Faculty and peer influnces on academic integrity: College cheating in Romania. Higher Education, 57, 267–282.

Trost, K. (2009). Psst, have you ever cheated? A study of academic dishonesty in Sweden. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 34(4), 367–376.

Unal, E. (2011). Examining the relationship between pre-service teachers’ ethical reasoning level and their academic dishonesty levels: A structural equation modelling approach. Educational Research and Reviews, 6(19), 983–992. https://doi.org/10.5897/ERR11.259

UNESCO Institute for Statistics. (2015). International Standard of Classification: Fields of Education and Training 2013 (ISCED-F 2013) - Detailed Field Descriptions. Retrieved from Montreal, C. (2013). International Standard of Classification: Fields of Education and Training 2013 (ISCED-F 2013) - Detailed Field Descriptions. http://uis.unesco.org/sites/default/files/documents/international-standard-classification-of-education-fields-of-education-and-training-2013-detailed-field-descriptions-2015-en.pdf. Accessed 19 Aug 2018

Verhoef, A. H., & Coetser, Y. M. (2021). Academic integrity of university students during emergency remote online assessment: An exploration of student voices. Transformation in Higher Education, 6, a132. https://doi.org/10.4102/the.v6i0.132

Walsh, L. L., Lichti, D. A., Zambrano-Varghese, C. M., Borgaonkar, A. D., Sodhi, J. S., Moon, S., . . . Callis-Duehl, K. L. (2021). Why and how science students in the United States think their peers cheat more frequently online: Perspectives during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal for Educational Integrity, 17(23). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40979-021-00089-3

Watson, G., & Sottile, J. (2010). Cheating in the digital age: Do students cheat more in online courses? Online Journal of Distance Learning Administration, XIII(I). https://www.westga.edu/~distance/ojdla/spring131/watson131.html

Wiley. (2022). New insights into academic integrity: 2022 update. 1–10. http://read.uberflip.com/i/1444056-academic-integrity-infographic-final/0. Accessed 19 June 2022

Yu, H., Glazner, P. L., Sriram, R., Johnson, B. R., & Moore, B. (2017). What contributes to college students’ cheating? A Study of Individual Factors Ethics & Behavior, 27(5), 401–422. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508422.2016.1169535

Zhang, Y., Yin, H., & Zheng, L. (2018). Investigating academic dishonesty among Chinese undergraduate students: Does gender matter? Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 43(5), 812–826. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2017.1411467

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Ives, B., Cazan, AM. Did the COVID-19 pandemic lead to an increase in academic misconduct in higher education?. High Educ 87, 111–129 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-023-00996-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-023-00996-z